Abstract

Trypanosome RNA editing is a massive processing of mRNA by U deletion and U insertion, directed by trans-acting guide RNAs (gRNAs). A U deletion cycle and a U insertion cycle have been reproduced in vitro using synthetic ATPase (A6) pre-mRNA and gRNA. Here we examine which gRNA features are important for this U deletion. We find that, foremost, this editing depends critically on the single-stranded character of a few gRNA and a few mRNA residues abutting the anchor duplex, a feature not previously appreciated. That plus any base-pairing sequence to tether the upstream mRNA are all the gRNA needs to direct unexpectedly efficient in vitro U deletion, using either the purified editing complex or whole extract. In fact, our optimized gRNA constructs support faithful U deletion up to 100 times more efficiently than the natural gRNA, and they can edit the majority of mRNA molecules. This is a marked improvement of in vitro U deletion, in which previous artificial gRNAs were no more active than natural gRNA and the editing efficiencies were at most a few percent. Furthermore, this editing is not stimulated by most other previously noted gRNA features, including its potential ligation bridge, 3′ OH moiety, any U residues in the tether, the conserved structure of the central region, or proteins that normally bind these regions. Our data also have implications about evolutionary forces active in RNA editing.

RNA editing of trypanosomes and related kinetoplastids is a fascinating form of mRNA maturation, posttranscriptionally deleting and inserting U residues in mitochondrial transcripts (1, 3, 18, 33–35). This editing occurs at multiple sites, contributing over half of the protein-coding residues of certain mRNAs, and progresses 3′ to 5′ on the pre-mRNA. Like so many forms of RNA processing, trypanosome editing utilizes small trans-acting RNAs, guide RNAs (gRNAs), which direct the sequence changes. These gRNAs consist of three main regions: a 5′ anchor sequence that hybridizes to the mRNA and identifies the editing site, a central guiding sequence that directs the mRNA editing to become its complement (using Watson-Crick and G:U pairing), and a 3′ oligo(U)tail that may tether the upstream, very purine-rich pre-mRNA (see Fig. 1).

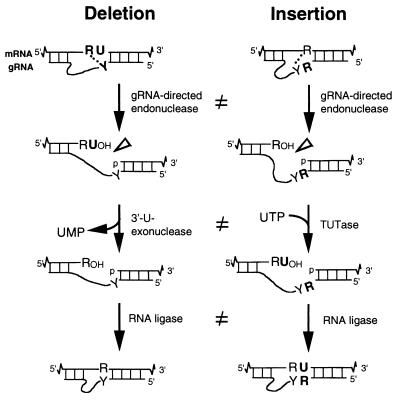

FIG. 1.

Current understanding of U deletion and U insertion. RNA editing is catalyzed by a complex with seven major polypeptides, two of which correspond to distinct ligases (12, 29). U deletion and U insertion involve gRNA-directed endonuclease cleavage of the pre-mRNA (shown by an arrowhead), either 3′-U-exo or TUTase acting on the upstream fragment, and RNA ligase rejoining the mRNA (10, 17, 32). R, purine(s); Y, pyrimidine(s). These two forms of editing use distinct cleavage activities (11) and distinct ligase enzymes (Cruz-Reyes et al., unpublished), and the 3′-U-exo is not a reverse TUTase reaction (10, 29), which is indicated by the unequal sign. gRNAs have three main portions: a 5′ region to anchor the gRNA to the mRNA just downstream of the editing site and direct the cleavage, a central region to guide the U deletions and insertions at mismatches in base pairing with the pre-mRNA, and a 3′ oligo(U) that may tether the very purine-rich upstream pre-mRNA. Many additional conserved gRNA features have also been noted (see the text). Dotted lines indicate potential base pairs that could serve in a ligation bridge.

The U deletion cycle at editing site 1 (ES1) of Trypanosoma brucei ATPase subunit 6 (A6) and the U insertion cycle at editing site 2 (ES2) of this RNA can each be reproduced in vitro (17, 31), using synthetic end-labeled pre-mRNA and synthetic gRNA plus crude mitochondrial extract (31) or more-purified fractions (2, 17, 24, 25, 29, 32). The simplest preparation that catalyzes U deletion and U insertion is a complex of seven major polypeptides (12, 29). Studies of these in vitro systems show that each editing cycle involves endonuclease cleavage of the pre-mRNA just 5′ of the anchor duplex, U removal by a 3′ U exonuclease (3′-U-exo) or U addition by terminal U transferase (TUTase), and mRNA religation (Fig. 1) (4, 10, 17, 32). Upon correct editing, the anchor duplex “zips up” to begin the next editing cycle, or if incorrect, the cleavage specificity initiates a proofreading cycle (10). The downstream cleaved mRNA fragment can also covalently join to the gRNA, forming a chimera (6). Previously considered intermediates in a transesterification-based editing mechanism (6, 9, 31), chimeras evidently form when gRNAs fail to efficiently tether the upstream cleaved mRNA (32).

Because U deletion and U insertion superficially appear to be parallel (Fig. 1) (10, 17, 32) and utilize the same simple protein complex (12), initial enzymatic models suggested that the same activities could catalyze their corresponding steps and even that the 3′-U-exo was a reverse TUTase reaction (for examples, see references 14 and 35). However, U deletion and U insertion in T. brucei now appear to be remarkably distinct. They utilize different endonuclease activities for their cleavages (11), different activities for their 3′-U-exo and TUTase (10, 29), and different ligase enzymes for their rejoinings (J. Cruz-Reyes et al., unpublished data); the editing complex does contain two distinct RNA ligases (29). Furthermore, U deletion and U insertion are optimized under different reaction conditions (12) and appear to have quite different gRNA requirements (Cruz-Reyes et al., unpublished). Therefore, findings discerned about one form of editing need not apply to the other. Leishmania tarentolae also exhibits U editing (1, 8, 19), but less is known about its mechanism, likely because the available in vitro system needs PCR for detection of U insertion, and U deletion remains to be observed.

T. brucei gRNAs have numerous conserved sequence features, structural motifs, and binding proteins, but little is known about which characteristics are critical for an in vitro editing cycle (Fig. 1). Foremost, the gRNA's anchor region selects the cognate pre-mRNA and specifies its cleavage location at the 5′ end of the base-paired anchor duplex (4, 10, 28, 32). The adjoining unpaired residue(s), which is a U(s) in the mRNA or a purine(s) in the gRNA, specifies deletion or insertion of the corresponding number of U residues (4, 17, 31). In fact, U deletion and U insertion are already distinguished at the initial cleavage step (11). Furthermore, the gRNA's 3′ oligo(U) is important, since its removal abolishes U deletion (32). One role of the oligo(U) is evidently to tether the very purine-rich upstream mRNA (5), likely favoring faithful editing rather than the competing chimera formation (7, 17, 18, 32). However, a gRNA construct with strengthened tethering (Trunc4) that suppressed chimera formation unexpectedly reduced the U deletion level (32) instead of increasing it as would be predicted if chimera formation competed with editing. In contrast, strengthened gRNA tethers were shown to increase U insertion levels (7, 16, 19). Thus, either tether strength affects the two kinds of editing differently or strengthened tethers should also augment U deletion but, for some reason, not with Trunc4.

Other gRNA features have also been considered important in the editing cycles. First, a critical role for the gRNA's natural 3′ OH moiety in U deletion was implicated, since its chemical modification appeared to inhibit this form of editing (32). However, 3′ gRNA modification did not prevent U insertion (7, 8, 19), again suggesting that U deletion may be different and should be reinvestigated. Another likely important gRNA feature is its complementarity with the mRNA in the residue just beyond the editing site (Fig. 1). This base pairing is needed to extend the anchor duplex for the next editing cycle (4) but has been suggested to also function in the current editing cycle, forming a ligation bridge that precisely positions the two mRNA ends to favor sealing of fully edited sites following complete U removal or complete U insertion (26, 32) (Fig. 1). Such adjacent base pairing has recently been shown to be important in U insertion, using a precleaved RNA assay (16) or full-round in vitro reactions (Cruz-Reyes et al., unpublished). A third gRNA feature that could be important for editing cycles is its large central guiding region, which can form a conserved higher-order structure and specifically bind to proteins (2, 15, 20, 22, 30). Fourth, specific proteins which bind to oligo(U) could also be important (20, 21, 23, 27, 36). Finally, the gRNA's common ∼60- to 75-nucleotide (nt) size and A+U bias could affect editing. It remains to be determined if these gRNA features are important for specifying U deletion. To date, only a few artificial gRNA constructs have been reported, and none were more active at in vitro U deletion than the natural gRNA.

This article reports that the A6 U deletion cycle utilizes only remarkably simple and largely unrecognized gRNA features. Foremost, the single-stranded character of a few gRNA and a few mRNA residues adjacent to the anchor duplex can affect U deletion >200-fold. Most other recognized gRNA features, including the potential ligation bridge, the 3′-terminal OH, and the guiding region, do not augment the U deletion cycle; the tether need not contain any U residues. Unexpectedly, simple artificial gRNA constructs lacking the guiding region can direct U deletion up to 100-fold more efficiently than natural A6 gRNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RNA identity and synthesis.

All RNAs are based on the natural T. brucei A6 pre-mRNA (3′ region) and its first (3′-most) cognate gRNA (31, 32). mRNAs are denoted by “m” plus the numbers of U's at ES2 and ES1, in that order, and natural-like gRNAs are denoted by “g” plus the numbers of guiding purines at these sites (11). Natural A6 pre-mRNA m[0,4] has no U's at ES2 and four U's at ES1, while parental gRNA g[2,1] has two guiding purines at ES2 and one at ES1. Artificial U-deletional gRNAs that lack the guiding region are denoted by “D” plus their length. Their diagrammed mRNA pairings are supported by nuclease cleavage studies (see below). In the base-pairing diagram of Fig. 2A, the lines at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the pre-mRNA represent 5′-GGAAAGGUUA GGGGGAG-3′ and 5′-AAUACUUACC UGGCAUC-3′, respectively, while the line at the 5′ end of the gRNAs represents 5′-GGAUAUA-3′.

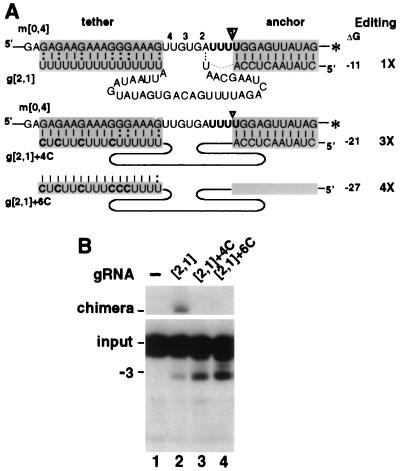

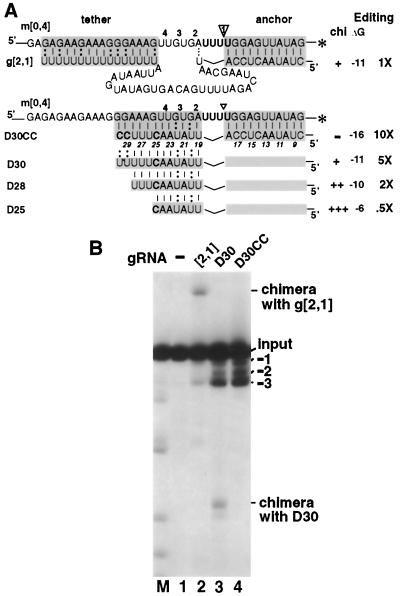

FIG. 2.

Strengthened tethering in the natural gRNA increases U deletion. (A) U-deletional RNA pairs using 3′-end-labeled mRNA, their predicted duplexes (shaded boxes), estimated ΔGtether (kcal/mol), and efficiencies of complete editing relative to the parental gRNA, denoted 1X, are illustrated. The ES1 cleavage site is indicated by an arrowhead, and ES2, ES3, and ES4 are marked 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Solid horizontal lines represent terminal residues (see Materials and Methods); dotted lines represent a phosphodiester bond; solid curved lines represent the wild-type guiding sequence; the asterisks indicate the 3′ end labels of the mRNA. (B) Autoradiogram of gel analyzing in vitro U deletion reactions with the indicated gRNAs, showing input pre-mRNA m[0,4], the complete (−3) U deletion product, and the position of the major U-less chimera with g[2,1], which have been confirmed by cloning and sequencing (data not shown). g[2,1]+6C shows a novel, somewhat shorter band that cloning and sequencing showed to be a gRNA ligation product involving an internally cleaved gRNA (not shown). Two films were used to span this 1-m long gel.

Templates and in vitro RNA preparation.

PCR amplification of templates for parental A6 m[0,4] and g[2,1], in vitro transcription, gel purification of single-sized products, and 3′ (or 5′) end labeling were performed as described previously (10, 32). Templates for modified gRNAs were PCR amplified using the parental 5′ oligonucleotide (which bears the T7 promoter) plus these mutagenic 3′ oligonucleotides: g[2,1]+4C (5′-GAGAAGAAAGA AAAAATAATT ATCATAT-3′), g[2,1]+6C (5′-GAGAAGAAAG GGAAAATAAT TATCATAT-3′), D30 (5′-AAAAAGTTAT AATGGAGTTA TAG-3′), D30CC (5′-GGAAAGTTAT AATGGAGTTA TAG-3′), D28 (5′-AAAGTTATAA TGGAGTTATA G-3′), D25 (5′-GTTATAATGG AGTTATAG-3′), D30CC (5′-GGAAAGTTGT AATGGAGTTA TAG-3′), D30CC" (5′-GGAAAGTTGT GATGGAGTTA TAG-3′), D32 (5′-GGAAAGTTGT GAGGTGGAGT TATAG-3′) D32a (5′-GGAAAGTTGT GGGGTGGAGT TATAG-3′), D32b (5′-GGAAAGTTGT GGGATGGAGT TATAG-3′), D33′ (5′-GGGAAAGTTG TAGGGTGGAG TTATAG-3′), D33 (5′-GGGAAAGTTA TAGGGTGGAG TTATAG-3′), D27 (5′-GTTGTGGGG TGGAGTTATA G-3′), and Anc+U16 (5′-AAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAGGAG TTATAG-3′). The PCR template was generally g[2,1] DNA, except for D33′ and D33, which used D32a as template. The tightly tethering artificial gRNAs D30CC, D30CC′, D30CC", D32, D32a, D32b, D33′, and D33 show no detectable chimera formation. In Anc+U16, the anchor is 1 nt shorter to prevent this terminal nucleotide from alternatively serving as the first residue of the tether and supporting both −3 and −4 U deletions (data not shown). The linear template for the mRNA-gRNA circle shown in Fig. 5 joined the m[0,4] 3′ end to the D30CC 5′ end via a double PCR using the parental 5′ oligonucleotide plus, first, the oligonucleotide 5′-AGTTATAGTA TATCCGATGC CAGG-3′, which extends the m[0,4] template with the first 15 nt of the gRNA and, second, the D30CC 3′ oligonucleotide. Its T7 transcript was kinase labeled and treated with T4 RNA ligase, and the abundant monomeric circular RNA was gel isolated. The circularity and identity of this RNA and its edited product were confirmed by sequencing RT-inverted PCR products prepared with diverging primers, both targeting mRNA sequences 3′ to the editing site (leftward primer, 5′-GTAAGTATTC TATAACTCC-3′; rightward primer, 5′-GTAATACGAC TCACTATAGG TTACCTGGCA-3′, the final 11 nt of which are complementary to the mRNA).

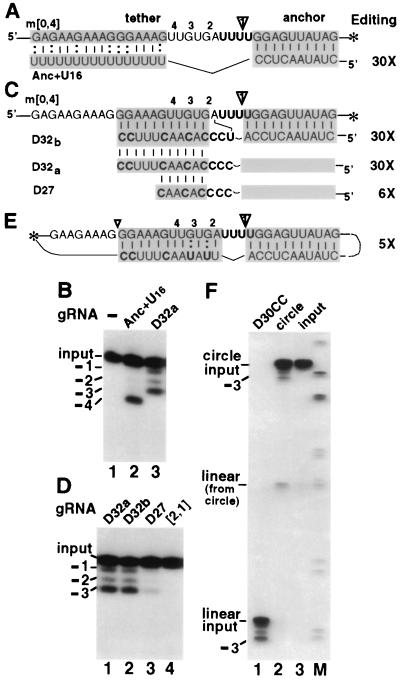

FIG. 5.

Roles of the guiding region, an adjacent complementarity, and the 3′ OH. (A, C, and E) U-deletional RNA pairs are shown as in Fig. 2A. The ΔGtether with m[0,4] are as follows: for Anc+U16, −11 kcal/mol; for D32a and D32b, −19.4 kcal/mol; and for D27, −9.4 kcal/mol. Anc+U16's anchor duplex is one residue shorter (to avoid an alternate pairing; see Materials and Methods); the most proximal of many possible pairings between its oligo(U) and the polypurine upstream mRNA is shown. Only g[2,1] and D27 direct appreciable chimera formation; probably because of its weak tether, D27 exhibits less U deletion, more chimeras, and more accumulated cleaved mRNA than D32a. Panel E shows circular RNA containing m[0,4] and D30CC sequences. Dots represent a phosphodiester bond. (B, D, and F) RNA editing reactions as in Fig. 2B. Panel D is underexposed to show editing with D32a and D32b; longer exposures demonstrate editing with g[2,1]. In panel F, editing reactions used D30CC and m[0,4] (lane 1), the circular mRNA/gRNA (lane 2), or the latter without editing factors (lane 3). The small amount of linear RNA in lane 2 is evidently not a U deletion intermediate, since it occurs in the absence of adenosine nucleotides (11). M, HpaII-cleaved pBR322.

Editing analysis.

Mitochondrial extract (2 × 1010 cell equivalents/ml) was prepared from procyclic T. brucei strain TREU 667, and the editing complex was purified by Q-Sepharose and DNA-cellulose chromatography (29). The 20-μl editing reaction mixtures were optimized for U deletion (12) and used ∼30 fmol of mRNA, ∼1.2 pmol of gRNA, and 0.5 μl (see Fig. 2 and 4), 1 μl (see Fig. 3 and 5), or 2 μl (see Fig. 6) of DNA cellulose fraction. Reactions generally lasted for 1 h but times could be shortened to decrease or lengthened to increase editing. Alternatively, U deletion was catalyzed using 0.5 to 1 μl of whole mitochondrial extract (∼2 to 4 μg of protein). Gels were 1 m long (9% polyacrylamide, 8 M urea in Tris-borate-EDTA) (11).

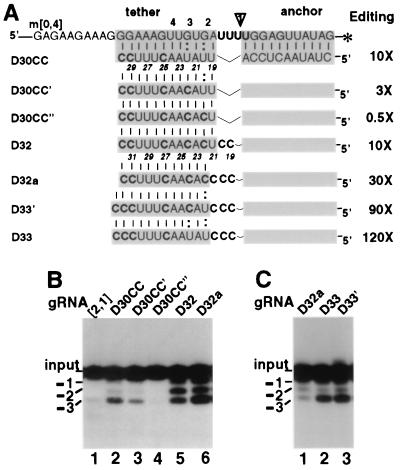

FIG. 4.

U deletion requires ss gRNA character adjoining the editing site. (A) U-deletional RNA pairs are shown as in Fig. 2A. The ΔGtether with m[0,4] are as follows: for D30CC, −16 kcal/mol; for D30CC, for −18.5 kcal/mol; for D30CC" and D32, −21.2 kcal/mol; for D32a −19.4 kcal/mol; for D33′,−21 kcal/mol; and for D33, −18.5 kcal/mol. Only g[2,1] directs appreciable chimera formation. (B and C) RNA editing reactions as in Fig. 2B. The U deletion with D30CC" is detected in longer exposures, generating a pattern that looks like a much lighter version of D32 (not shown). Panel C is a lighter exposure than panel B and of a reaction using less-than-optimized conditions.

FIG. 3.

Efficient U deletion by gRNAs with altered tethers and no guiding region. (A) U-deletional RNA pairs are shown as in Fig. 2A. Their chimera formation is also indicated (chi). (B) RNA editing gel as in Fig. 2B. The partial (−2 and −1) products are also indicated. Note that chimera size varies with gRNA length. Markers (M) are a PhyM (A+U) digest of the input mRNA (13) (see Materials and Methods).

FIG. 6.

gRNA attributes important for a U deletion cycle. (A) U deletion with D33′ and D33, using 2-h reactions and 2 μl of the purified editing complex. (B) Characteristic features of gRNAs for U deletion sites are illustrated. Those shown to be important or not for U deletion in this study and the anchor duplex shown to be critical in previous works (see text) are indicated.

Representative editing products were gel isolated and sequenced with PhyM RNase (Pharmacia), which cleaves after A and U residues, and/or by cDNA sequencing (not shown). (PhyM generates fragments with 5′ OH ends that migrate nearly 1 nt offset from fragments bearing 5′ P ends generated by the editing cleavages [13].) Sequence analysis of the products formed with several artificial gRNAs confirms that the −3 band indeed represents correctly edited mRNA while the −1 and −2 bands represent mRNA partially edited at the correct site (not shown).

Each gRNA was analyzed in multiple independent experiments (generally more than three), often using more than one editing complex preparation. The relative levels of U deletion with the various gRNA constructs were reproducible (±∼30%), even when assayed using different editing complex and whole extract preparations. (Thus, editing levels are reported as relative to a control gRNA, not as absolute levels which vary depending on the editing complex preparation and the amount used.) To quantitate activity of the gRNAs that are 30- to 100-fold more active for in vitro U deletion than the parental one, it was necessary to use reactions in which the parental gRNA directed editing of <1% of input mRNA. We also ran control editing reactions with the purified editing complex using radiolabeled artificial gRNAs and unlabeled mRNA to show that the majority of termini of that gRNA remain largely unaltered, implying that selective gRNA degradation does not explain the artificial gRNAs' differential efficiencies.

Confirmation of predicted gRNA:mRNA pairings.

Formations of the predicted pairings between pre-mRNAs and artificial gRNAs, illustrated in Fig. 3 to 5, were experimentally substantiated using trypanosome nucleases specific for the 5′ end of duplex regions. The existence of the anchor duplex and its 5′ end on the mRNA were confirmed by the editing complex cleaving at the U deletion site, with fragments sized relative to sequencing markers (reference 13 and data not shown). The existence of the tether duplexes and their 5′ ends on the mRNA were confirmed for all gRNAs ending in C by cleavage using a structure-specific trypanosome endonuclease (unpublished data). Between these anchor and tether duplexes are only a few intervening residues, with no obvious pairing partners. We therefore consider the pairings illustrated in Fig. 3A, 4A, and 5A, C, and E rather well verified. For the pseudonatural gRNAs shown in Fig. 2 (+4C and +6C), the anchor and tether pairings were similarly confirmed. However, the structure that may form within the sizable guiding region of the natural-like gRNAs was not scored and thus is not illustrated. Furthermore, for Anc+U16 and g[2,1], the tethering location(s) of their oligo(U) within the upstream polypurine mRNA also was not scored; the most proximal of many possible locations is illustrated.

Free energy calculations.

Free energies were estimated using the Mfold folding package of M. Zuker (http://mfold.mbcmr.unimelb.edu.au/). The stability of the tether duplex (left shaded box in panels A of all figures) was calculated using the gRNA 3′ portion appended to the 3′ end of the upstream pre-mRNA fragment via six nonpairing residues (5) at 26°C, the optimal culture temperature for T. brucei.

RESULTS

Stabilized tethering increases U deletion.

We are studying editing at ES1 of A6 pre-mRNA, the paradigm system for in vitro analysis of U deletion (31). To discern relevant gRNA features, we mutated parental gRNA g[2,1] and examined its ability to direct this model U deletion cycle. Through strengthening of its tethering potential, we first examined whether natural gRNA limits U deletion by weakly tethering the upstream mRNA, which in turn allows chimera formation. This has been a favored hypothesis, even though a previous experiment using the multiply altered Trunc4 gRNA construct (32) appeared to contradict it. We thus used natural-like gRNA in which 4 or 6 U's of the 3′ U16 track were converted from weak U:G pairs to tight C-G pairs. This markedly increased its potential tethering strength (estimated ΔGtether [Fig. 2A]) and eliminated chimera formation (Fig. 2B). Notably, these changes increased U deletion efficiency three- to fourfold whether catalyzed with the purified editing complex (Fig. 2B) or whole extract (data not shown). This enhanced U deletion demonstrates that the oligo(U) tether in the natural A6 gRNA indeed limits in vitro U deletion.

Further increased U deletion by gRNAs with a stabilized tether and no guiding region.

Because the oligo(U) changes in the natural gRNA with its large guiding region could potentially have additional effects on secondary structure, we created simpler gRNA constructs that have artificial tethers of various strengths and lack the guiding region. These turned out to support unexpectedly active U deletion. Constructs that significantly improve the ΔGtether by supplementing or largely replacing the natural 3′ U16 tether with non-U base-pairing residues (D30CC [Fig. 3A] and other constructs not shown) not only inhibited chimera formation as expected but, notably, also directed up to 10-fold more U deletion than parental g[2,1] (Fig. 3B and data not shown). Intriguingly, a gRNA construct that differs from D30CC in only two distal residues and exhibited approximately the same ΔGtether as parental g[2,1] and the same amount of chimera formation (D30) (Fig. 3) still directed approximately fivefold more U deletion than the parental gRNA (Fig. 3B, lane 2 versus lane 3). The increased U deletion with D30CC versus D30 supports the conclusions that strengthened tethering enhances this editing and that an oligo(U)-like tether sequence is not important for it. Furthermore, the efficacy of D30 suggests that the gRNA's natural guiding region, which is absent from these artificial gRNAs, is unnecessary—indeed inhibitory—for this U deletion cycle.

We also examined similar derivatives of D30 with still shorter tethers and weaker ΔGtether (D28 and D25) (Fig. 3A). They direct considerably more chimera formation and levels of U deletion which are lower but still substantial relative to parental gRNA (Fig. 3A), reinforcing both the importance of tethering and the inhibitory effect of the guiding region on the U deletion cycle. The artificial gRNA constructs of Fig. 3A thus indicate that two regions of the natural T. brucei A6 gRNA negatively affect in vitro U deletion. First, its 3′ tether does not fully retain the upstream mRNA, and second, its guiding region appears to unexpectedly inhibit this editing.

Single-strandedness abutting the editing can affect U deletion 200-fold.

Since stronger tethering of natural and artificial gRNAs augments U deletion (Fig. 2 and 3), we prepared still-more-tightly-tethering derivatives of D30CC (Fig. 4 and others not shown; none of these yielded detectable chimera formation). Several gRNAs were created with extensions at the 3′ end that further strengthen the tether, and none had appreciable effects on U deletion efficiency (data not shown). However, conversion of only one or two tether U's in weak G:U pairs near the editing site to tightly base-pairing C's, D30CC′ and D30CC" (Fig. 4A), surprisingly diminished U deletion, by ∼3- and ∼20-fold, respectively (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 to 4). We addressed two possible reasons for this strong inhibition. The first concerned sequence effects: U's could be stimulatory or C's could be inhibitory at proximal positions. The second concerned structural effects: this editing could require single-stranded (ss) character in adjoining residues which could be achieved by breathing of weakly duplexing proximal residues but abolished by a strong proximal duplex. To distinguish these possibilities, we distanced the tight tether duplex of D30CC′′ from the editing site by adding two proximal unpaired C residues in the gRNA, forming D32 (Fig. 4A). Strikingly, that small change increased the U deletion level ∼20-fold (Fig. 4B, lane 4 versus lane 5). This stimulation by added unpaired C's refutes the former scenario and supports the notion that U deletion requires residues with an ss character adjoining the editing site.

To examine whether the tight proximal duplex remaining in D32 might still limit U deletion, we prepared additional gRNA constructs that further increased proximal single-strandedness. Changing only the first paired residue of D32 from a U to a nonpairing C extended the gRNA and mRNA single-strandedness by 1 nt, forming D32a (Fig. 4A), and it augmented accurate U deletion approximately threefold (Fig. 4B, lanes 5 and 6). This D32a gRNA thus directed U deletion ∼30-fold more actively than parental g[2,1]. Separate studies have shown that partial U deletion products, whose relative abundance diminished with D32a, arose from a proximal mRNA duplex inhibiting the 3′-U-exo (Cruz-Reyes et al., unpublished data).

The proximal duplex of this D32a was then still further weakened by changing its first C to a U, converting its first tight G-C pair to a weak G:U pair, forming D33′ (Fig. 4A). This change enhanced the level of U deletion approximately another threefold (Fig. 4C, lanes 1 and 2). Because D33′ should affect structure 4 nt away from the editing site, U deletion efficiency depends on single-strandedness several nucleotides away. Subsequently, the proximal duplex of this D33′ was additionally weakened by changing its next C to a U, also converting the second tight G-C pair to a weak G:U pair, forming D33 (Fig. 4A). This final D33 construct directs U deletion approximately fourfold more efficiently than does D32a (Fig. 4C, lane 3), which is >100-fold more efficient at U deletion than is parental gRNA. (To observe this full increase in editing efficiency, it is of course necessary to use reaction conditions where ≪1% of input mRNA becomes edited with parental gRNA.) The constructs of Fig. 3 and 4 thus document that limited nucleotide changes which affect single-strandedness abutting the editing site modulate U deletion efficiency by >200-fold (compare D30CC" to D33). Furthermore, the enhanced U deletion of D32, D33′, and D33 is observed in whole mitochondrial extract as well as with the purified editing complex (data not shown). It should be noted that single-strandedness abutting the editing site had not been previously considered a factor in editing efficiency.

Most conserved gRNA features are not stimulatory for A6 U deletion. (i) Guiding region.

The unexpectedly high levels of in vitro U deletion with gRNAs lacking the natural guiding region (especially D30, which tethers approximately as tightly as parental gRNA) (Fig. 3) indicate that the natural guiding region is not only unnecessary but also strongly inhibitory for this editing. To directly assess this inference in a more natural context, we formed Anc+U16, which is just like parental g[2,1] except that it lacks the entire 35-nt guiding region plus one anchor residue (Fig. 5A; see Materials and Methods). Amazingly, this simple construct is one of our most effective gRNAs. It directs the in vitro A6 U deletion ∼30-fold more efficiently than parental gRNA and generates virtually only the fully edited form (−4 RNA) (Fig. 5B). Correlating with its great activity, Anc+U16 should maintain many unpaired mRNA residues near the editing site as well as provide ss character to the critical gRNA residues through its naturally breathable G:U-rich tether (Fig. 5A). Anc+U16 thus directly shows that the natural guiding region of g[2,1] impedes U deletion ∼30-fold (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, Anc+U16 is also ∼30-fold more active than g[2, 1] at directing U deletion in whole extract (data not shown).

(ii) Subsequent base pairing.

At all natural U deletion sites, the gRNA residue abutting the anchor duplex is complementary to the pre-mRNA residue just upstream of the U's being deleted (Fig. 1). This is needed for the anchor duplex to zip up to the next editing site (4) but also has been hypothesized as being important in the current editing cycle by enabling an RNA bridge that precisely positions the mRNA ends for ligation specifically upon complete U removal (32). Such a potential gRNA bridge is maintained in many of our gRNA constructs (Figs. 2 to 4) but is absent in D32 and D32a and its derivatives D33′ and D33 (Fig. 4A). Because these include our most efficient gRNAs, bridging by a potential gRNA-mRNA adjacent pairing cannot be important to precisely position the mRNA termini and favor ligation of U deletion. Indeed, with this series of constructs, the U deletion efficiency increases as their structure contains more unpaired gRNA and mRNA residues separating the mRNA ends that will be ligated (Fig. 4A), further disavowing the ligation bridge model for U deletion. However, to address whether a potential ligation bridge could be advantageous in otherwise comparable gRNAs, the noncomplementary proximal C of D32a was changed to a U, reforming a potential ligation bridge by restoring complementarity to the A residue of the mRNA abutting the editing site (D32b) (Fig. 5C). The level of U deletion with D32b is the same as with D32a (Fig. 5D, lanes 1 and 2), providing additional support to the deduction that a potential ligation bridge is not important for an efficient in vitro U deletion cycle.

(iii) 3′ oligo(U), length, and A+U bias.

The terminal oligo(U) tail of natural gRNAs can bind specific proteins, which could be important in editing (23, 36; reference 27 and references therein), and the tethers of all previously published functional gRNA constructs for both U deletion and U insertion contain either an uninterrupted or a slightly hyphenated oligo(U) (7, 19, 32). Yet the tether of our 30-fold active D32a had only three U's (Fig. 4), suggesting that an oligo(U) may be not critical. We thus eliminated all these U's (D27) (Fig. 5C). This shortened gRNA with no U's at all beyond the anchor region still directed much more U deletion than parental g[2,1] (Fig. 5D, lanes 3 and 4; see legend). We conclude that efficient in vitro U deletion does not require any U's in the gRNA tether.

The gRNAs of the D32 series, especially D27, are considerably less than half the length of the parental 76-nt gRNA and lack the natural gRNAs' A+U bias (15). Their directing of ample U deletion (Fig. 4 and 5C and D) indicates that these features are also not critical for this editing.

(iv) 3′ OH.

Earlier studies suggested that A6 U deletion requires the gRNA's 3′ OH (32). To address this, we prepared a 102-nt circular RNA containing both D30CC and m[0,4] sequences (Fig. 5E; see Materials and Methods). Much like the separate linear gRNA and mRNA, this RNA with no ends directs U deletion considerably more efficiently than parental g[2, 1] (Fig. 5F and data not shown). The accuracy and circularity of its −3 product were confirmed by reverse transcription-inverse PCR amplification and sequencing (see Materials and Methods). Therefore, efficient U deletion can be directed without the 3′ OH and linearity typical of gRNAs.

Editing efficiency.

Systems for full-cycle in vitro RNA editing have traditionally appeared disappointingly inefficient, with at most a small percentage of input mRNA achieving U deletion or U insertion when using T. brucei extract or extract fractions (10, 12, 17, 32) and considerably lower levels needing PCR for detection when using L. tarentolae extract (1, 8, 19). However, we find that U deletion can be remarkably robust with our optimized gRNA constructs when using either the purified T. brucei editing complex or whole extract (Fig. 3 to 6). Indeed, the D32a, D32b, and Anc+U16 gRNAs can direct U deletion on ∼15% of input mRNA under our standard reaction conditions and on >30% of input mRNA when using reduced amounts of mRNA (data not shown). Furthermore, reactions with the most efficient D33′ and D33 gRNAs can edit >60% of the mRNA (Fig. 6A). Thus, in vitro U deletion can be very efficient.

DISCUSSION

Trypanosome RNA editing has generated considerable interest, largely because of its unprecedented nature, massive scale, and intriguing guiding RNAs. This editing consists of numerous sequential cycles of U deletion and U insertion, both involving three protein-catalyzed reactions (Fig. 1) (10, 17, 32). A purified complex of seven major polypeptides catalyzes both kinds of editing cycles (12, 29). Nevertheless, the U deletion and U insertion reactions examined in vitro are remarkably different and use distinct enzymatic activities of the editing complex (references 11 and 12 and references therein; see the introduction). Little has yet been discerned about the critical features of a gRNA, besides that it directs editing just upstream of its anchor duplex with the cognate pre-mRNA and that the number of adjoining gRNA purines or mRNA U's determines the number of U's to add or remove (Fig. 1) (4, 10, 17, 32); these residues also specify the distinct cleavage activities for U deletion or U insertion (11). However, gRNAs share many other features, all of which have been implicated or speculated as being relevant in editing. Yet, only a few gRNA constructs have been assessed for U deletion (32) and for U insertion cycles (7, 8, 19), and no general understanding of which specific gRNA features direct efficient editing have yet emerged. Strengthening of the tether has appeared to inhibit U deletion (32) but to stimulate U insertion (7, 19), and the gRNA's 3′ OH has appeared important for U deletion (32) but not for U insertion (7, 8, 19). Recent data indicate that pairing as a potential ligation bridge is important in a partial U (16) or complete (Cruz-Reyes et al., unpublished) insertion reaction. We wanted to assess the gRNA features important for the in vitro U deletion cycle. Furthermore, since in vitro editing has traditionally appeared very inefficient, we hoped to obtain gRNAs with increased efficacy.

Limited gRNA features enhance U deletion >100-fold.

We examined the effects of specific gRNA features on U deletion using various A6 RNA constructs. Our data show that gRNA features critical for an efficient U deletion cycle are surprisingly simple (Fig. 6B). In addition to forming the anchor duplex, the gRNA need only maintain the ss character of a few adjacent residues and tether the upstream pre-mRNA. The finding that artificial gRNAs with these simple features enhance in vitro U deletion up to 100-fold over the natural gRNA (Fig. 4 to 6) is striking. Furthermore, these U deletion reactions yielding >60% of the edited product (Fig. 6A) represent a marked increase over the few percent previously observed as maximal in vitro (for examples, see references 11, 17, and 32). It now makes the efficiency of the in vitro U deletion system appear comparable to that of the in vitro system standardly used to analyze processing events like mRNA splicing. As in other forms of RNA processing examined in vitro and in vivo, it seems likely that the U deletion reaction occurs still more rapidly in vivo than in vitro.

(i) Single-strandedness.

A6 U deletion is highly dependent on the single-strandedness of the first approximately three residues adjoining the editing site, and it is further stimulated by the ss character of a few additional residues (Fig. 6B). This ss character can be provided by unpaired residues or by ones in a weak duplex where G:U pairing favors breathing (Fig. 4). Changing the ss character of only a few critical residues affects in vitro U deletion efficiency >200-fold (Fig. 4). Confirming that it is the resultant single-strandedness, not the identity of the altered nucleotide, that affects editing efficiency, introduced C residues that decrease single-strandedness diminish editing (D30CC′ and D30CC"), while introduced C residues or other residues that increase single-strandedness stimulate editing (D32, D32a, D33′, and D33). Furthermore, this dependence on ss character is similarly observed whether the U deletion is catalyzed using purified editing complex (Fig. 4) or whole mitochondrial extract (data not shown), so it does not appear to be a peculiarity of a particular protein preparation.

In earlier studies of editing, such single-strandedness was not considered for designing gRNAs. Notably, the previous Trunc4 gRNA constructed to strengthen tethering, which had paradoxically reduced U deletion efficiency (32), can form the same tight 10-bp duplex with the mRNA abutting the editing site as our most inhibitory gRNA, D30CC′′ (Fig. 4). Our data suggest that its editing, like that of D30CC′′, is strongly inhibited by insufficient adjacent ss character, which overrides the potential stimulation from strengthened tethering.

Examination of the mRNA and gRNA sequences surrounding many natural trypanosome U deletion sites suggests that these sites maintain sufficient abutting ss character. Generally, this critical region could form only a very weak duplex due to frequent G:U interactions and quite hyphenated pairing arising from mismatches at all subsequent editing sites.

(ii) Tether.

The gRNA must also tether the upstream cleaved mRNA to prevent its dissociation, which in turn allows chimera formation (Fig. 2 and 3) (32). The strong implication that preventing such upstream mRNA loss should increase productive U deletion is supported here by four sets of matched gRNAs. Within each set, the gRNAs are identical except for their tethering efficiencies, which were altered by different means: changing G:U to G:C pairing within the oligo(U) (g[2,1]+4C and +6C versus g[2,1]) (Fig. 2) or within an artificial tether (D30 versus D30CC) (Fig. 3) or changing the tether's overall length by removing U's (D30, D28, D25) (Fig. 3) or other residues (D32a vs. D27) (Fig. 5C). In all these sets, the gRNA with the stronger tether generates more edited mRNA and less of the chimera than the sibling gRNA with looser tethering.

In regions distal to the editing site, increasing tether strength beyond that needed to suppress chimera formation generally had minimal effect on U deletion efficiency (see Results). However, other changes in artificial gRNA tethers had additional effects. For instance, when a duplex was strengthened too near the editing site, it inhibited U deletion by diminishing adjacent ss character, as seen with D30CC′ and D30CC" (Fig. 4) and presumably also Trunc4 (32) (see above). It is reassuring that a similar conclusion about tether importance can be drawn from natural-like gRNAs and small artificial gRNAs (Fig. 2 to 4).

It appears that natural gRNA effectively exploits the pairing properties of U residues for its tethering. It utilizes the ability of U to pair with A and G to create a universal oligo(U) tether, since the upstream mRNA is virtually polypurine (5), while simultaneously exploiting the weakness of G:U pairing to ensure sufficient single-strandedness for U deletion when near the editing site (Fig. 4 and 5A). Nonetheless, limited tethering by natural gRNAs may well impede both U deletion and U insertion in vitro. For U deletion, this is seen in Fig. 2. For U insertion, three recent papers report a gRNA with strengthened tethering which augments that editing slightly in T. brucei (7) or considerably in L. tarentolae and T. brucei (16, 19), although the latter pair of reports used constructs that also eliminated the guiding region, which our data suggest could be responsible for much of their increased activity. Curiously, however, identical tethers can affect U deletion and U insertion differently; most gRNAs designed for U insertion that are analogous to the stimulatory g[2,1]+4C and g[2, 1]+6C of Fig. 2 instead repress that form of editing (Cruz-Reyes et al., unpublished).

(iii) Other noted gRNA features.

Besides the unexpected requirement for gRNA and mRNA proximal single-strandedness and the predicted importance of the tether, none of the many other previously implicated conserved gRNA features appear important for highly efficient in vitro U deletion in our studies. These include, first, the natural gRNA:mRNA complementarity immediately beyond the U's being eliminated, which could function as a gRNA bridge to precisely align the U-deleted mRNA halves for ligation, in a manner analogous to how U5 or self-splicing intron sequences align exons in splicing (32). However, constructs D32a, D33′, and D33 show that such bonding is not needed for highly active in vitro U deletion (Fig. 4). Enhanced partial U deletion products also implied this result (12). Second, the entire A6 guiding region—half the length of natural gRNA—is dispensable for the examined U deletion; indeed it is markedly inhibitory (Fig. 3, 4, and 5B). Therefore, neither the guiding region's potential structure nor the proteins whose binding it directs (15, 30) appear needed for this in vitro U deletion cycle (see also reference 22). Third, the gRNA's natural 3′ oligo(U) can be replaced by sequences that contain no oligo(U) or even no U's at all and thus evidently functions in this U deletion only to tether the upstream mRNA (Fig. 2 to 4 and 5D). It follows that oligo(U) binding proteins also are not important for this editing cycle (references 27 and 36 and references therein), and accordingly, identified oligo(U)-binding proteins and guiding region-binding proteins are not part of the editing complex of seven major polypeptides (29). Fourth, the gRNA does not require a 3′ OH or any end (Fig. 5F), contrary to earlier inferences (32) but in accordance with its lack of requirement in U insertion (7, 8, 19). Fifth, the gRNA can vary from one-third to twice the standard length and lack the natural A+U bias (Fig. 5D and F), implying that those features also are not critical for in vitro U deletion. Nonetheless, any of these gRNA features could have effects in other contexts and especially in multicycle in vivo editing.

Parental gRNA and editing in vivo.

It is notable that parental A6 gRNA directs in vitro U deletion only ∼1% as efficiently as our best artificial gRNA constructs. This can partly be attributed to incomplete tethering (Fig. 2 and 3; see above), but the major effect is a marked inhibition by the guiding region (Fig. 4 and 5). Indeed, when the guiding region is simply removed, the remaining natural anchor and tether support an ∼30-fold-enhanced U deletion (Fig. 5B). Separate studies show that the parental gRNA appears nonoptimal for each of the component reactions of the U deletion cycle (Cruz-Reyes et al., unpublished). Furthermore, the stimulation of U deletion by the D32/D33 gRNA series and by Anc+U16 relative to that of parental gRNA is observed with both the purified editing complex and whole extract, so it is not an artifact of a particular protein preparation.

Nature uses trans-acting small RNAs in numerous kinds of cellular RNA processing events to guide precise cleavages (e.g., RNase P for tRNA and U7 for histone mRNA), to direct other RNA modifications (e.g., snoRNAs for rRNA), and to help retain the flanking segments during removal of nucleotides (e.g., U5 and group I in splicing), possibly somewhat reminiscent of the gRNA's roles in RNA editing. However, it appears to be rare that studying relevant features of such trans-acting RNAs enables the ready design of artificial constructs that are 2 orders of magnitude more active than the natural one. We speculate that this is possible for the U deletion cycle because gRNAs have evolved to maximize the overall multisite editing process, not the single U deletion cycle, and these additional aspects of editing may be more limiting and involve somewhat different gRNA features. In particular, several conserved gRNA features which are not important for the single U deletion cycle are likely needed for sequential editing cycles, including a sizable guiding region (to direct these cycles), its natural secondary structure (likely helping to constrain its effective length), the natural complementarity just beyond the editing site (allowing the anchor duplex to extend), the 3′ oligo(U) (enabling a virtually universal tether as editing progresses along the mRNA), and proteins in addition to the basic editing complex. Thus, it seems probable that all conserved gRNA features function in various aspects of the complete editing process. Nonetheless, the ability to so greatly optimize a natural function of a small RNA was an unexpected positive outcome of our studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the laboratory and Paul Englund for helpful discussions.

We thank the NIH (GM 34231) for funding this research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfonzo J, Thiemann O, Simpson L. The mechanism of U insertion/deletion RNA editing in kinetoplastid mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3751–3759. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.19.3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen T E, Heidmann S, Reed R, Myler P J, Göringer H U, Stuart K D. Association of guide RNA binding protein gBP21 with active RNA editing complexes in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6014–6022. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.6014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arts G, Benne R. Mechanism and evolution of RNA editing in kinetoplastida. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1007:39–54. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(96)00021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blum B, Bakalara N, Simpson L. A model for RNA editing in kinetoplastid mitochondria: “guide” RNA molecules transcribed from maxicircle DNA provide the edited information. Cell. 1990;60:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90735-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blum B, Simpson L. Guide RNAs in kinetoplastid mitochondria have a nonencoded 3′ oligo(U) tail involved in recognition of the preedited region. Cell. 1990;62:391–397. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90375-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum B, Sturm N, Simpson A, Simpson L. Chimeric gRNA-mRNA molecules with oligo(U) tails covalently linked at sites of RNA editing suggest that U addition occurs by transesterification. Cell. 1991;65:543–550. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90087-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgess M, Heidmann S, Stuart K. Kinetoplast RNA editing does not require the terminal 3′ OH of the gRNA terminus but can inhibit in vitro U insertion. RNA. 1999;5:883–892. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrne E, Connell G J, Simpson L. Guide RNA-directed uridine-insertion RNA editing in vitro. EMBO J. 1996;15:6758–6765. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cech T. RNA editing: world's smallest introns. Cell. 1991;64:667–669. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90494-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cruz-Reyes J, Sollner-Webb B. Trypanosome U-deletional RNA editing involves gRNA-directed endonuclease cleavage, terminal U-exonuclease and RNA ligase activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8901–8906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruz-Reyes J, Rusché L, Piller K, Sollner-Webb B. Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing: adenosine nucleotides inversely affect U deletion and U insertion reactions at mRNA cleavage. Mol Cell. 1998;1:401–409. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cruz-Reyes J, Rusché L, Sollner-Webb B. Trypanosoma brucei U insertion and U deletion activities co-purify with an enzymatic editing complex but are differentially optimized. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3634–3639. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.16.3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruz-Reyes J, Piller K, Rusché L, Mukherjee M, Sollner-Webb B. Unexpected electrophoretic migration of RNA with different 3′ termini causes a RNA sizing ambiguity that can be resolved using nuclease P1-generated sequencing ladders. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6059–6064. doi: 10.1021/bi972868g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajduk S. Defining the editing “reaction.”. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:1–2. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(96)30039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermann T, Schmid B, Hermann H, Goringer H U. A three-dimensional working model for a guide RNA from Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2311–2318. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Igo R P, Jr, Palazzo S S, Burgess M L, Panigrahi A K, Stuart K. Uridylate addition and RNA ligation contribute to the specificity of kinetoplastid insertion RNA editing. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8447–8457. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.22.8447-8457.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kable M, Seiwert S, Heidmann S, Stuart K. RNA editing: a mechanism for gRNA-specified uridylate insertion into precursor mRNA. Science. 1996;273:1189–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5279.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kable M, Heidmann S, Stuart K. RNA editing: getting U into RNA. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:162–166. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapushoc S, Simpson L. In vitro uridine insertion RNA editing mediated by cis-acting guide RNAs. RNA. 1999;5:656–669. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299982250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koller J, Muller U, Schmid B, Missel A, Kruft V, Stuart K, Goringer H U. Trypanosoma brucei gBP21. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3749–3757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Köller J, Nörskau G, Paul A S, Stuart K, Göringer H. Different Trypanosoma brucei guide RNA molecules associate with an identical complement of mitochondrial proteins in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1988–1995. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.11.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambert L, Muller U, Souza A, Goringer H U. The involvement of gRNA-binding protein gBP21 in RNA editing—an in vitro and in vivo analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1429–1436. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.6.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leegwater P, Speijer D, Benne R. Identification by UV cross-linking of oligo(U)-binding proteins in mitochondria of the insect trypanosomatid Crithidia fasciculata. Eur J Biochem. 1995;227:780–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madison-Antenucci S, Sabatini R, Pollard V, Hajduk S. Kinetoplast RNA editing associated protein 1 (REAP-1): a novel editing complex protein with repetitive domains. EMBO J. 1998;17:6368–6376. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McManus M T, Adler B K, Pollard V W, Hajduk S L. Trypanosoma brucei guide RNA poly(U) tail formation is stabilized by cognate mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:883–891. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.883-891.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore M, Sharp P. Site-specific modification of pre-mRNA: the 2′ hydroxyl group at the splice site. Science. 1992;256:992–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1589782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelletier M, Miller M, Read L. RNA binding properties of the mitochondrial Y-box protein RBP16. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1266–1275. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.5.1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piller K, Rusché L, Cruz-Reyes J, Sollner-Webb B. Resolution of the RNA editing gRNA-directed endonuclease from two other endonucleases of Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. RNA. 1997;3:279–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rusché L, Cruz-Reyes J, Piller K, Sollner-Webb B. Purification of a functional enzymatic editing complex from Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. EMBO J. 1997;16:4069–4081. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.4069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmid B, Riley G, Stuart K, Goringer H U. The secondary structure of guide RNA molecules from Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3093–3102. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.16.3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seiwert S, Stuart K. RNA editing: transfer of genetic information from gRNA to precursor mRNA in vitro. Science. 1994;266:114–117. doi: 10.1126/science.7524149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seiwert S, Heidmann S, Stuart K. Direct visualization of uridylate deletion in vitro suggests a mechanism for kinetoplastid RNA editing. Cell. 1996;84:831–841. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith H, Gott J, Hanson M. A guide to RNA editing. RNA. 1997;3:1105–1123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sollner-Webb B. Trypanosoma RNA editing: resolved. Science. 1996;273:1182–1183. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5279.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stuart K, Allen T E, Heidmann S, Seiwert S D. RNA editing in kinetoplastid protozoa. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:105–120. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.1.105-120.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vanhamme L, Perez-Morga D, Marchal C, Speijer D, Lambert L, Geuskens M, Alexandres S, Ismaili N, Goringer U, Benne R, Pays E. Trypanosoma brucei TBRGGl, a mitochondrial oligo(U)-binding protein that co-localizes with an in vitro RNA editing activity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21825–21833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]