Abstract

B cells represent a relatively minor cell population within both the healthy and diseased central nervous system (CNS), yet they can have profound effects. This is emphasized in multiple sclerosis, in which B cell-depleting therapies are arguably the most efficacious treatment for the condition. In this Review, we discuss how B cells enter and persist in the CNS and how, in many neurological conditions, B cells concentrate within CNS barriers but are rarely found in the parenchyma. We highlight how B cells can contribute to CNS pathology through antibody secretion, antigen presentation and secretion of neurotoxic molecules, using examples from CNS tumours, CNS infections and autoimmune conditions such as neuromyelitis optica and, in particular, multiple sclerosis. Overall, understanding common and divergent principles of B cell accumulation and their effects within the CNS could offer new insights into treating these devastating neurological conditions.

Subject terms: Multiple sclerosis, Autoimmune diseases

Although B cells represent only a minor cell population in the central nervous system (CNS), they can contribute to CNS pathology — most notably in multiple sclerosis — through antibody and effector molecule secretion and antigen presentation. Here, Jain and Yong discuss the roles of B cells in the CNS and examine the potential for targeting these cells in various neurological conditions.

Introduction

B cells were originally identified through studies searching for the cellular source of antibodies, which led to the discovery of antibody-secreting plasma cells and, eventually, their precursors, the B cells. Similarly, the study of B cells in the context of central nervous system (CNS) disorders has often started as a result of antibody detection in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or at sites of injury. The first indication that B cells could contribute to multiple sclerosis (MS) was the detection of antibodies in CSF1. The study of the antigenic targets of these antibodies led to the discovery of the autoimmune diseases neuromyelitis optica (NMO) and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody-associated disorder and their designations as separate entities from MS. Many other autoimmune encephalitides have been discovered, such as anti N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis, wherein antibodies target various neuronal proteins and contribute to these disorders1. Antibodies may also influence neurodegenerative processes in Parkinson disease and Alzheimer disease1 as well as in CNS infections2.

The notion that B cells can contribute to CNS pathology independently of antibody production was first hinted at in MS, where the depletion of CD20+ B cells was shown to be an effective treatment3. This was an unexpected result as B cells represent a minor population of immune cells in the CNS during MS and, as we will discuss in this review, are not appreciably found in the CNS parenchyma at sites of damage but are instead found behind barriers of entry into the CNS. Since this discovery, the study of how B cells contribute to CNS immunity and pathology independently of antibody production and from a distance are a growing field of study. There are still many unanswered questions regarding whether B cells contribute to these disorders from within or outside the CNS, which B cell subsets are responsible for promoting pathology and repair, and what mechanisms B cells use to influence CNS pathology. In this Review, we will focus specifically on the role of B cells within the CNS, covering their representation and localization in health and CNS disorders. We review how B cells enter and persist in the CNS and what effector functions they use to promote pathology with a particular focus on MS as the vast amount of relevant data has come from the MS field. These discussions emphasize B cells as important regulators of CNS responses in both homeostasis and disease.

A refresher on B cells

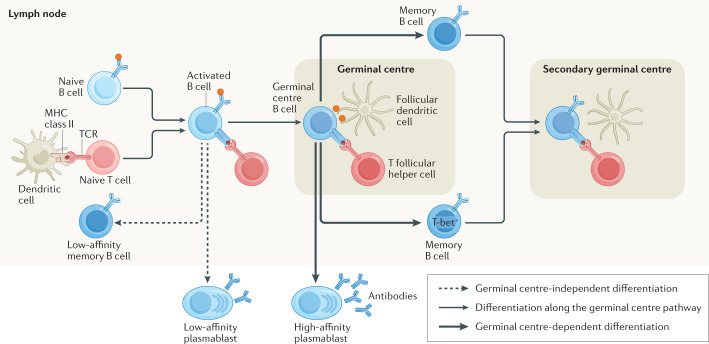

For a thorough refresher on B cell immunology, we suggest reading the reviews cited here and in Fig. 1 as we will only cover basic B cell immunology. Mature B cells are those that have completed development. They are broadly separated into antigen-experienced or antigen-inexperienced (naive) B cells. Naive B cells can be further differentiated into B1 B cells, follicular B cells (also known as B2 B cells) and marginal zone B cells. Naive B cells are recruited to participate in immune responses through B cell receptor (BCR) stimulation initiated by antigen binding in combination with co-stimulatory signalling or in combination with T cell help to induce a T cell-dependent immune response4 (Fig. 1). The products of T cell-dependent immune responses are differentiated B cell subsets such as memory B cells, T-bet+ memory B cells and plasma cells.

Fig. 1. T cell-dependent B cell differentiation.

T cell-dependent B cell differentiation is initiated when B cells engage with their antigen through their B cell receptor (BCR) and a cognate T cell response is activated (left side of figure). Activated B cells and T cells then move to the border of the B cell follicle and T cell zones by modifying their expression of chemokine receptors119 and form cognate pairs through physical interactions. These interactions can induce B cell class-switch recombination to change their initial IgD and IgM isotypes to IgG, IgA or IgE120. These interactions drive the differentiation of mostly IgM+ low-affinity memory B cells, low-affinity plasmablasts, and pre-germinal centre B cells that re-enter the B cell follicle with T follicular helper cells to seed a new germinal centre4. The germinal centre is composed of germinal centre B cells, T follicular helper cells and supportive cells, such as follicular dendritic cells, that organize and maintain the germinal centre environment4. In the germinal centre, T follicular helper cells induce somatic hypermutation in germinal centre B cells and direct them to differentiate into high-affinity short-lived and high-affinity long-lived plasma cells and into T-bet– or T-bet+ memory B cells4,12. Memory B cells can then later participate in an immune response if they are re-exposed to antigen (secondary germinal centre).

B cells contribute to immunity through antibody production, antigen presentation and production of secreted products. When antibodies bind their targets, they can initiate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, complement-dependent cytotoxicity or phagocytosis5. Antigen presentation is a process wherein B cells endocytose antigens, then process and load them onto MHC class II molecules to present to CD4+ T cells. Antigen presentation by B cells is essential in maintaining germinal centres and to activate and polarize CD4+ T cell responses. Another major mechanism employed by B cells to affect immune responses is the secretion of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Regulatory B (Breg) cells generally produce anti-inflammatory cytokines while antigen-experienced B cells generally secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines3.

Where are B cells in the healthy CNS?

Before immune cells can enter the CNS parenchyma, they must first pass through restrictive barriers of the post-capillary venules (blood–brain barrier (BBB)), meninges (blood–meningeal barrier) and choroid plexus (blood–CSF barrier). Here, we provide a brief description of how these barriers interact with immune cells; for more in-depth descriptions see refs6,7.

Post-capillary venules in the CNS are surrounded by a thick extracellular matrix with barrier properties maintained by endothelial cells, pericytes, astrocytes, microglia and neurons; this barrier retains immune cells around the blood vessel in areas known as Virchow–Robin spaces8. The meninges is separated into the dura mater that is in contact with the skull, arachnoid mater and the innermost pia mater that overlies the parenchyma7. Blood vessels are present in the subarachnoid space of the meninges where immune cells can migrate across these blood vessels into the subarachnoid space and CSF. Directly associated with the pia mater, astrocyte end-feet maintain the glial limitans, a barrier that prevents immune cell entry into the parenchyma. During inflammation, immune cells may be able to cross the pia mater to enter the CNS parenchyma7 although this process is incompletely described. Immune cells entering the choroid plexus first extravasate across capillaries to enter the choroid plexus stroma; they then cross the choroid plexus epithelial cell barrier to enter the CSF6.

In mice, B cells are rarely found in the healthy CNS parenchyma and are only found in small numbers in CSF, the choroid plexus and the subdural meninges. However, B cells are constitutively present in the dural meninges and represent ~15–30% of the total CD45hi cells in this location9–11. The vast majority of B cells in the dura meninges are B2 B cells and a large fraction of these are immature B cells generated in the skull’s bone marrow10,11. Most mature CNS B cells are naive IgM+ cells10 with unmutated BCRs although there are some IgA+ B cells11. Furthermore, B cells in the CNS are mainly tissue resident cells that were generated locally10,11. The capacity of peripheral B cells to take up residence in the healthy CNS is limited in young mice but increases as mice age and this increase is primarily due to age-associated B cells — whose phenotype overlaps with T-bet+ B cells12 — accumulating in the brain10. In young animals IgA+ plasma cells dominate the meninges13 but, as mice age, IgG+ and IgM+ plasma cells become more common10. Of note, the population of IgA+ plasma cells found in the healthy CNS is partially derived from IgA+ plasma cells that are generated in the gut13.

In humans, B cells and plasma cells are rarely found in the parenchyma of the healthy CNS although small numbers are reported14,15. They are present in low numbers in perivascular spaces14–16 and more frequently found in the meninges16, particularly in the dura mater11,13. B cells can be detected in healthy CSF in humans; however, few plasma cells are found, corresponding with the low levels of antibody seen in CSF17,18.

B cells in neurological conditions

B cells can be recruited to the CNS as a result of CNS infection13 and even due to sleep disruption19. Indeed, in many neurological conditions, increased levels of IgM, IgA and IgG are seen in CSF17. Here, we review B cells in the context of CNS cancers, infections of the CNS and autoimmune disorders affecting the CNS finally focusing on MS. The locations of B cells and plasma cells in these disorders are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Cancers of the CNS

Glioblastoma is a deadly tumour that arises within the CNS. The immune cell composition of glioblastoma predominantly consists of microglia and macrophages, while B cells and T cells are present in small numbers in these tumours. By flow cytometry, 0.66% of the immune cells found in glioblastoma are B cells20. In meningiomas, which are tumours that form in the meninges, B cell frequencies are highly variable but, on average, they represent 0.03% of all cells in the tumour21. Cancers of the CNS also include those that have metastasized from extra-cranial locations. Patients with B cell lymphomas can have metastasis to the CNS22, which present as solid tumours of B cells retained within the meninges or perivascular spaces or as diffuse tumours that spread through the parenchyma22. Whether B cells promote or suppress tumour growth likely depends on the types of B cells in the tumour. Glioblastoma promotes the conversion of B cells into Breg cells that sustains tumorigenicity23. However, in the right inflammatory environment, B cells can elicit an anti-glioblastoma immune response24.

CNS infections

Many patients infected with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) develop signs of neurological dysfunction with evidence of pathology ongoing in the CNS25. Single-cell sequencing-based studies have either found no evidence of B cell and plasma cell expansion in CSF26 or have reported expansion27 of these populations in patients with neurological manifestations of COVID-19.

CNS pathology induced by coronaviruses is not unique to COVID-19, as many other coronaviruses, including the original severe acute respiratory syndrome virus and Middle East respiratory syndrome28 virus, drive pathology within the CNS. In mouse models of CNS coronavirus infection, peripheral plasmablasts, memory B cells and naive B cells29 are recruited into the CNS. Plasma cells enter the parenchyma, where they can contribute to localized antibody production that is associated with protection from infection30, whereas naive B cells stay within the perivascular and meningeal compartments31. Thus, the mouse models of CNS coronavirus infection support a protective role of B cells entering the CNS.

Evidence of B cells playing a protective role from within the CNS is also seen in other CNS-trophic viral and bacterial infections. In these conditions, virus-specific or bacteria-specific antibodies are produced within CSF and the parenchyma of infected CNS tissue where antibodies are presumed to contribute to viral and/or bacterial clearance2,32,33.

Autoimmune diseases

B cells have a major role in contributing to immune responses through their capacity to secrete antibodies. However, the secretion of antibodies can be detrimental in certain circumstances as exemplified by the autoimmune CNS disorders NMO (which is associated with anti-aquaporin 4 antibodies), anti-NMDAR encephalitis (associated with anti-NMDAR antibodies) and MOG antibody-associated disorder1. B cells and plasma cells within the CNS may also contribute to neuropsychiatric forms of systemic lupus erythematosus based on studies in animal models34 and also on the finding that oligoclonal bands of immunoglobulin are detected in the CSF of 26.5% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus who have neuropsychiatric manifestations35.

There is evidence of antibody production from clonally expanded plasma cells within the CSF of patients with NMO or with anti-NMDAR encephalitis36,37. Nonetheless, only patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis show a concentration of pathogenic antibodies within the CNS and, in patients with MOG antibody-associated disorder and patients with NMO, most autoreactive antibodies are produced peripherally1,36. Indeed, unlike in patients with MS, where oligoclonal bands of immunoglobulin are consistently detected in CSF, only 15–30% of patients with NMO have oligoclonal bands of immunoglobulin in CSF, suggesting that plasma cell expansion in the CSF of patients with NMO is not robust1.

B cells in MS

MS is an inflammatory and degenerative disease of the CNS where oligodendrocytes and neurons are lost in white and grey matter leading to the accumulation of neurological deficits. The progression of MS is broadly separated into a relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS) phase, in which neurological deficits manifest and recede, and a phase of secondary progressive MS (SPMS; if progression follows RRMS) or primary progressive MS (PPMS), wherein neurological disability accumulates with minimal periods of recovery. Monoclonal antibodies that deplete CD20+ B cells are highly effective in treating the relapsing phase of MS and, in some patients, also the progressive forms of MS3. Although B cells can contribute to MS pathology from the periphery38, there is considerable evidence that B cells enter CNS barrier regions to participate in CNS pathology.

Locations of B cells in the CNS of patients with MS

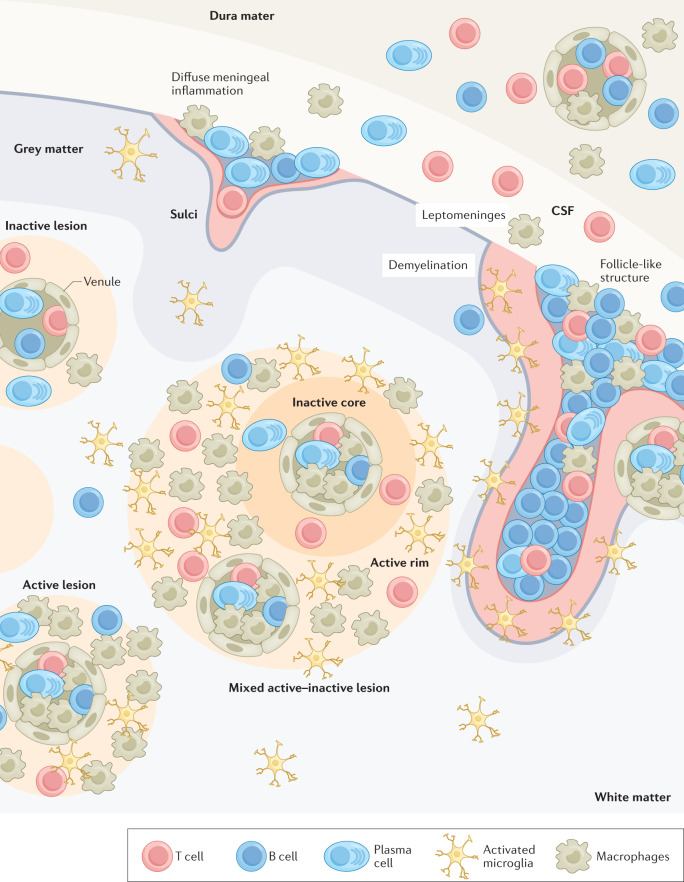

MS lesions can be broadly segregated into grey matter lesions, where the cortical locations are often associated with meningeal inflammation, and white matter lesions. The latter can be active lesions filled with immune cells, mixed active–inactive lesions that have an actively demyelinating rim associated with macrophage/microglia and a demyelinated immunologically inactive centre, or inactive demyelinated lesions (Fig. 2). Active and mixed active–inactive lesions can be further subdivided into demyelinating and post-demyelinating based on whether myelin proteins are present or absent within macrophage/microglia, respectively. We encourage the reader to follow the recent consensus39 on the nomenclature of MS lesions that addresses the ambiguities of old naming conventions present in older papers.

Fig. 2. Locations of B cells in multiple sclerosis lesions.

Depictions of lesions are approximations of the average number of B cells relative to T cells and macrophage/microglia in the meninges and in grey and white matter lesions. B cell and plasma cell populations are expanded in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with multiple sclerosis but only represent 0.5–11% and 0.25–12% of total immune cells, respectively32,44,48,121. Grey matter lesions can be split into those that have diffuse B cell infiltration or the formation of large collections of B cells in B cell aggregates in the meningeal space that typically form at the bottom of sulci16,40–42,52. Relative to diffuse B cells in the meningeal space, B cell aggregates are associated with increased infiltration of macrophages, T cells and some plasma cells into the central nervous system parenchyma, grey matter demyelination and proximal microglial activation41,42,52,54,55,58. In white matter lesions, B cells and plasma cells are commonly found in the perivascular spaces of post-capillary venules but are rarely found in the parenchyma15. Plasma cells are found in the same locations as B cells but are more likely to enter the parenchyma of the central nervous system than B cells regardless of the lesion type14,15.

In patients with MS, B cells and plasma cells in the CNS are primarily found in the meninges and perivascular locations but they are also present in the parenchyma in small numbers40–42 (Fig. 2). There is preliminary evidence of B cells entering the choroid plexus in MS43 but this requires confirmation. B cells and plasma cells are also expanded in the CSF from patients with MS relative to that from healthy humans44,45, especially during periods of active disease where class-switched B cells and plasma cells clonally expand46. B cells are also 1–3 times more prevalent in the CSF of patients with RRMS relative to those with progressive MS47,48.

Based on post-mortem studies, meningeal and perivascular B cell aggregates are highly variable in MS, where they can be nearly absent in the lesions of some patients or dominate the lesions of others15. Meningeal and perivascular B cells are more numerous in RRMS and SPMS relative to PPMS, whereas plasma cells are more prevalent in progressive over RRMS14,15. B cells are more common in the parenchyma and perivascular spaces of active lesions relative to mixed active–inactive or inactive lesions whereas plasma cells are common in mixed active–inactive or inactive lesions14,15,49,50. Both B cells and plasma cells are rare in normal-appearing white matter14,49,50.

Cortical lesions associated with meningeal inflammation often have B cells that largely remain in the meninges15. In one study using high resolution MRI analysis of patients with MS, meningeal inflammation was found in ~33% of patients with progressive MS and in ~19% of patients with RRMS51, although the specific percentages can vary between studies. Meningeal B cell inflammation can be diffuse or extensive, the latter often associated with large ‘follicle-like’ structures42. These structures are referred to as follicle-like due to their resemblance to B cell follicles in secondary lymphoid organs, and they are characterized by separate zones of B cells and T cells and by large numbers of associated plasma cells42,52 (Fig. 2). As the resemblance of these structures to follicles remains controversial, we will refer to them as B cell aggregates. Based on post-mortem histology studies, the frequency of B cell aggregates in SPMS is estimated to be ~40%16,40,52. Similar studies in PPMS found that ~30% of PPMS have B cell aggregates although these meningeal aggregates do not achieve the same levels of organization seen in SPMS41,52. A similar frequency of B cell aggregates between MS subtypes is found in spinal cords of patients with MS although B cell aggregates are less common than in the brain42. Generally, patients that have one B cell aggregate in their brain are more likely to have additional B cell aggregates throughout their CNS42,52.

B cell invasion of the CNS in patients with MS or in animal models of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) has been studied in sufficient detail to provide an overview of the specific B cell subsets encountered in the CNS (Supplementary Table 2).

Association of B cells with MS lesions

An important question is whether the B cells in the CNS of patients with MS are contributing to disease directly or whether they are simply bystanders attracted to the CNS by the inflammatory environment. Suggesting an active role, patients that have a CSF immune cell repertoire biased towards B cells and plasma cells over other immune cell types show faster disease progression53. When comparing cortical lesions that do or do not have B cell aggregates in post-mortem samples, individuals with B cell aggregates are more likely to have transitioned earlier to being wheelchair-bound and to have died earlier in both PPMS and SPMS16,40,41,52,54. In a study of SPMS autopsies with or without B cell aggregates in the meninges, there is a strong correlation between the presence of B cell aggregates and cortical demyelination54. When meningeal inflammation is not segregated by the presence of B cell aggregates in patients with SPMS, there is an inconsistent and weak correlation between the degree of meningeal immune cell infiltration and cortical demyelination, suggesting that B cell aggregates are the primary locations driving cortical demyelination41,52. Meningeal B cell aggregates may also be associated with demyelination in adjacent white matter42,49,55,56; however, this relationship has not been found in all studies52,54.

B cell aggregates are also associated with pronounced local neuronal damage57. Biopsies taken from patients during early MS or following clinically isolated syndrome (which is the first manifestation of a demyelinating event) suggest that meningeal inflammation, either diffuse or concentrated in density in the meninges, is associated with demyelination in the cortex but that neuronal loss is only seen underneath dense aggregates in the meninges of subpial lesions57,58. Similar results have also been seen in post-mortem studies comparing patients with SPMS with or without B cell aggregates41,52 and this damage can even extend to the spinal cord42. Neuronal loss typically occurs in a gradient from the upper layers of the cortex and progresses inwards54 and is associated with apoptotic markers in neurons58. Indeed, the presence of B cell aggregates in the meninges is associated with faster cortical thinning54. This gradient of damage emanating away from the meningeal B cell aggregates suggests that B cells are secreting factors that diffuse into the surrounding CNS parenchyma and either directly damage CNS cells or may indirectly injure them by promoting inflammatory polarization of microglia as iNOS+ TNF+ phagocytes are found in proximity to B cell aggregates54. Nonetheless, while prominent meningeal inflammation is associated with the upregulation of inflammatory cytokines locally and within CSF, it is also associated with increased expression of IL-10 in both MS59 and EAE60. Thus, while B cell aggregates are associated with worse pathology, some components may also inhibit inflammation.

B cell aggregates may also affect the recruitment of other cell types into the parenchyma of the CNS. The parenchyma and small vessels in the cortex of areas associated with B cell aggregates are seen to have more CD8+ T cells, B cells, macrophages and plasma cells, particularly in the upper layers of the cortex16,54,55 (Fig. 2). CD4+ T cells and macrophages also accumulate in the meninges associated with B cell aggregates16,55.

Although the relevance of B cells in white matter inflammation is less well researched, one study found that the absence of B cells from white matter lesions is associated with slower and less severe disease progression, reduced T cell infiltration into lesions, lower incidence of mixed active–inactive lesions, and reduced incidence and intensity of oligoclonal bands50. Furthermore, another study that separated white matter lesions by the presence or absence of IgM or IgG deposits found that there is more B cell and plasma cell infiltration into white matter lesions when immunoglobulins are present, particularly for lesions containing IgG deposits49. Indeed, IgG deposition in lesions is associated with increased B cell and plasma cell infiltration into perivascular spaces, the parenchyma of the lesion, and increased B cell influx into the meninges near the lesion. Thus, B cells and plasma cells in white matter lesions contribute to MS pathology.

Recruitment and survival in the CNS

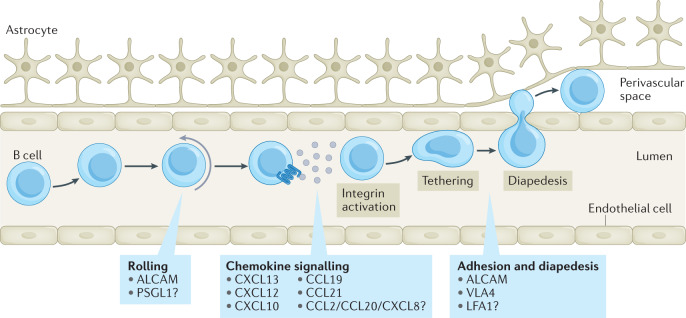

Much of what is known of B cell recruitment into the CNS comes from the MS literature. B cells can be recruited through the BBB, meningeal barriers and choroid plexus. Each of these sites differs with respect to structure but the overall process of moving from blood into these locations proceeds similarly (Fig. 3). Below, we will outline the mechanisms B cells use to pass through these barriers. Of note, T helper 17 (TH17) cells play an important role in opening the BBB and creating an environment for B cells to persist in the CNS, adding another layer of complexity to CNS B cell recruitment and persistence beyond what is discussed here61.

Fig. 3. Mechanisms of B cell recruitment into the CNS.

Immune cells are recruited into the central nervous system (CNS) by first rolling along the lumen of the blood vessel and being activated by locally produced cytokines. Activation of B cells, including by chemokines found on endothelial cells, then induces conformational changes in integrins, allowing high affinity interactions and firm tethering to the vessel; this enables cells to migrate across the endothelial cell layer into CNS barriers such as the perivascular space6,7. Although this process is not fully understood in the context of B cell entry into the CNS, several molecules shown in the boxes are known to affect their migration into the CNS at distinct stages whereas other molecules remain contentious or inadequately studied. CXCL, CXC-chemokine ligand; CCL, CC-chemokine ligand.

Rolling stage of B cell recruitment

Mice with genetic deletion of L-selectin (also known as CD62L), used by B cells to enter lymph nodes, show no deficiency of B cell infiltration into the CNS in the EAE model62. Indeed, B cells in the CNS of animals with EAE have low levels of L-selectin expression63 and the ligands for L-selectin are not well represented in EAE or MS lesions64; this suggests that L-selectin is not important for B cell recruitment into the CNS. One factor known to affect the rolling stage is the adhesion molecule ALCAM, which is upregulated on activated B cell subsets in MS65. ALCAM-deficient B cells roll at a faster rate on activated endothelial cells in vitro and ALCAM-blocking antibodies reduce disease severity and B cell recruitment into the CNS in mice with EAE65. Nonetheless, deletion of this single molecule does not completely prevent rolling on the endothelium, suggesting that other molecules affect the rolling stage of B cell recruitment.

Chemokines associated with B cell entry

Several chemokines associated with B cell migration have been studied in MS and EAE, including CXC-chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), CXCL12, CXCL13, CC-chemokine ligand 19 (CCL19) and CCL21. Each of these is known to affect specific B cell subsets and have different patterns of expression in MS lesions (Supplementary Table 3). Three other chemokines associated with B cell entry into the CNS based on in vitro studies are CCL20, IL-8 (also known as CXCL8) and CCL2 (refs66,67); however, in vivo evidence of a role for these chemokines is lacking in MS or EAE. Additionally, CC-chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) is overexpressed on CSF B cells in MS46 but it is unknown whether this affects B cell migration into the CNS.

Integrins and cell adhesion molecules

B cells express several integrins and cell adhesion molecules that facilitate their entry into the CNS. ALCAM promotes B cell diapedesis across brain endothelial cells65. Other important molecules are the integrin LFA1 and its cell adhesion molecule ligand ICAM1, both of which are upregulated on activated B cells in MS65. Blocking ICAM1 reduces human B cell migration across brain endothelial cell layers in culture65,66 but there is no in vivo evidence supporting this.

The best characterized molecule affecting B cell trafficking into the CNS is VLA4. This integrin is expressed highly on activated B cells in EAE and MS65,68 and is needed for B cells to cross brain endothelial cells in vitro65,66. In mouse models, deletion of VLA4 on B cells reduces B cell recruitment into the CNS69,70 and leads to reduction of EAE severity in B cell-dependent EAE70. Nonetheless, the effects of VLA4 blockade on EAE severity could be due to inhibition of peripheral B cell activation69. Blocking VLA4 in patients with MS is known to affect memory B cell trafficking3 leading to the concentration of memory B cells in blood corresponding with therapeutic benefit68. In contrast, treating patients with MS with anti-VLA4 antibodies led to no changes in B cell and plasma cell numbers in CSF, and biopsies of white matter lesions showed slight elevations in plasma cell density71. Overall, the mouse data strongly supports the idea that VLA4 affects B cell recruitment into the CNS whereas the human data suggests that some but not all B cell types are affected.

Antigen-specificity in recruitment

Activated T cells, regardless of their antigen specificity, are recruited to the CNS; however, only the T cells that encounter their antigen in the CNS are retained at this site in large numbers over time72. In the context of inflammation, B cells are recruited to the CNS in an antigen-independent manner that does not appear to follow the same rules as T cell recruitment72. Similarly, plasma cells specific for ovalbumin protein, rotavirus and non-self-antigens can be recruited into the CNS during EAE73,74 and can even persist as long-lived cells73. Thus, specificity for an antigen within the CNS is not explicitly required for B cells to take up residence in the CNS.

B cell survival in the CNS

The primary factors that influence B cell survival are BAFF and APRIL, both of which are available in MS lesions (Supplementary Table 3). Mature B cells are dependent on BAFF and, as they commit to plasma cell differentiation, they become increasingly more dependent on APRIL75,76. In contrast, memory B cells are much less dependent on survival factors relative to other B cell subsets76. Beyond BAFF and APRIL, astrocytes make undefined survival factors that promote the survival of B cells77. Plasma cell survival is enhanced by fibronectin and hypoxic conditions75, which can be found in MS lesions.

Another important factor that influences B cell and plasmablast survival in the CNS is their interaction with T cells. Both activated B cells and plasmablasts are susceptible to cell death but can be rescued by CD4+ T cell help78. These interactions are likely to occur given that autoreactive T cell clones derived from the CNS of patients with MS induce the proliferation of autoreactive B cells, suggesting that they form stable interactions38. Furthermore, invasion of the CNS by T follicular helper cells in EAE is associated with B cell population expansion in the CNS79. Thus, B cell–T cell interactions are likely important in maintaining B cells in the CNS.

B cell recruitment and survival in other CNS diseases

CXC-chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3) expression by plasma cells is associated with plasma cell entry into the CNS in NMO80 and viral encephalomyelitis30. Additionally, the CXCR3 ligands, CXCL10 and CXCL9, are upregulated in the CNS during viral encephalomyelitis30. In B cell lymphoma and in the healthy CNS, CXCL12 is expressed highly on the blood vessel endothelium, resulting in B cell recruitment into perivascular spaces81. However, CXCL12 also promotes egress from perivascular spaces unless countered by astrocyte-derived CCL19, which results in B cell accumulation in perivascular spaces and entrance to the parenchyma. Notably, the same study showed that increased expression of VCAM1 and ICAM1 on the blood endothelium in itself is not sufficient for B cell retention in the CNS. Many B cell lymphomas also express IL-15 that can induce the expression of CXCR3 and PSGL1, a selectin that can influence the rolling stage of recruitment, further promoting CNS recuitment82.

Despite high expression of the B cell survival factor receptors BAFF-R, BCMA and TACI by B cell lymphomas, there is no increase in BAFF expression in the CNS during CNS lymphoma relative to healthy CNS tissue83. By contrast, in a mouse model of CNS viral infection, there is evidence of increased BAFF and APRIL expression within the CNS84. Thus, in combination with the data from the MS literature, inflammation in the CNS is likely needed to induce increased expression of these survival factors.

B cell functions in MS lesions

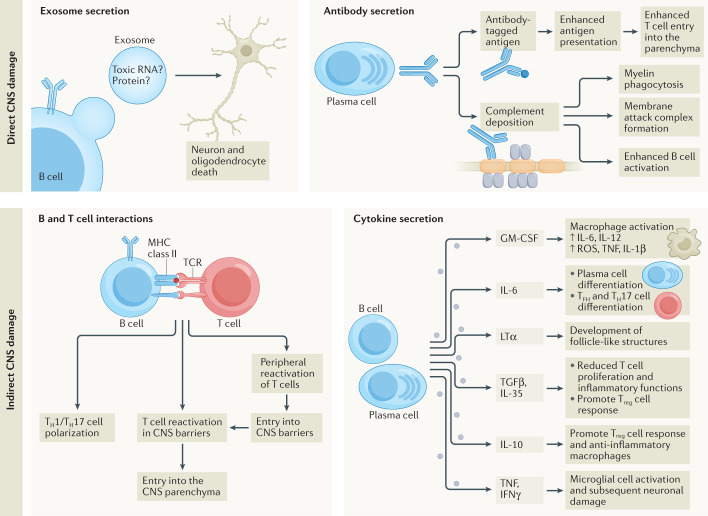

B cells as direct mediators of damage

Antibodies contribute to the pathology of MS lesions and in animal models through several different mechanisms, including opsonization, initiation of complement deposition, facilitating B cell and T cell activation, and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (Fig. 4). Of note, there is currently no consistently identified autoantigen target for antibodies in MS85 although antibodies are seen in MS lesions.

Fig. 4. Direct and indirect mechanisms that B cells use to affect multiple sclerosis pathology.

B cells can directly damage the central nervous system (CNS) using secreted molecules, including exosomes that induce death in oligodendrocytes and neurons, through unknown mechanisms (top left panel). Antibodies directly contribute to multiple sclerosis pathology by facilitating T cell reactivation in CNS barriers, promoting their migration into the parenchyma122, and by promoting the deposition of complement on myelin86 to enhance myelin phagocytosis88,123, membrane attack complex formation on myelin86, and the enhanced activation of B cell immune responses124 (top right panel). B cells can indirectly affect CNS pathology by inducing the differentiation of autoreactive T helper 1 (TH1) cell and TH17 cell responses in the periphery and within the CNS, in part through CD80 and CD86 upregulation (bottom left panel). However, B cells can also inhibit T cell responses through expression of PDL1 (not depicted). B cell-derived secreted cytokines also affect CNS pathology (bottom right panel): GM-CSF promotes macrophage-driven pathology102; IL-6 enhances plasma cell differentiation and survival, T follicular helper (TFH) cell differentiation, and TH17 polarization125,126. Lymphotoxin-α (LTα) is important for organizing large clusters of B cells in the meninges and for the formation of ‘follicle-like’ structures61. TNF and IFNγ are associated with microglial cell activation and neuron and oligodendrocyte death105–107. TGFβ1 and IL-35 reduce T cell proliferation and inflammatory T cell polarization and promote regulatory T (Treg) cell responses112,114. IL-10 affects T cells similarly111,117 but also alters macrophage polarization and may promote remyelination127. ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Some patients with MS have what are referred to as ‘pattern II lesions’, which have antibody and complement deposits in white matter86, providing the potential of formation of a membrane attack complex that can be destructive (Fig. 4). Individual lesions within the same patient can differ, with some lesions having IgM or IgG deposits but not others87. Most active, mixed active–inactive and inactive lesions have either IgM or IgG deposits, with IgG being more common87. Various antibody isotypes are detected in MS lesions and each has typical deposition patterns. IgG and IgM are found in lesions in proximity to demyelinated axons, degrading myelin and myelin debris, dying cells, and within macrophages49,87,88. Both IgM and IgG have been associated with oligodendrocytes in lesions, normal appearing white matter, and in newly forming lesions87,88. IgA is reported in lesions typically bound to axons and vasculature89. However, it remains unclear whether the pathology of these lesions is driven by CNS-derived or peripherally produced antibodies as therapeutic plasma exchange that removes circulating serum antibodies benefits these subjects90. In favour of CNS-produced antibodies contributing to antibody deposition, antibodies from the CSF of patients with RRMS or with progressive MS bind human cerebellum sections91. Similar results have been produced using cloned antibodies derived from single B cells, plasma cells or antibodies from CSF92 albeit not in all studies93,94. Thus, the question of whether antibodies are pathogenic in MS is equivocal.

Another possibility that has been highlighted more recently is that B cells may be contributing to MS in a non-conventional manner: through the production of pathogenic microvesicles or exosomes. The evidence for this comes from results showing that large secreted particles from B cells induce death in cultured oligodendrocytes and neurons95,96, which was attributed to secreted exosomes95 (Fig. 4). Currently, there is no obvious mechanism by which these exosomes are inducing cell death in their targets or evidence to show whether exosomes are produced by B cells in the CNS in vivo.

B cells indirectly promote CNS damage

In patients with MS and in animals with EAE, it is likely that B cells in the CNS can promote injury indirectly by supporting T cell responses through physical interactions15,38,42,63 given the close association of T cells and B cells in perivascular and meningeal compartments (Fig. 4). In EAE, B cells in both the periphery and the CNS upregulate the co-stimulatory molecule CD80, suggesting that they are primed for interaction with T cells63,97. Indeed, autoantigen-driven B cell–T cell interactions influence the incidence and induction of relapses, timing of disease onset, and chronicity of EAE79,97–99. These interactions primarily influence TH1 cell and/or TH17 cell polarization of CD4+ T cells and induce waves of T cell infiltration into the CNS from the periphery and within the CNS79,97,98,100.

The above is consistent with a recent study showing that memory B cells induce autoreactive T cell expansion in patients with MS during remission periods, ultimately activating these T cells to enter the brain and reactivating them again within the CNS38. Inflammatory memory B cell subsets that highly express the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 concentrate within the CSF of patients with MS, suggesting that B cells in the CNS are primed to interact with T cells44,68,101. This is partially explained by inflammatory astrocytes producing soluble factors that promote the expression of CD86 on B cells77. Overall, there is considerable evidence for a pathogenic role for B cell and T cell interactions in MS and EAE.

Another emerging and important role for B cells in MS is their capacity to make pro-inflammatory cytokines that can modify the inflammatory environment to activate cells such as macrophages and/or microglia and T cells. There is evidence of peripheral B cells expressing several inflammatory cytokines in MS, including GM-CSF, TNF, IL-6 and lymphotoxin-α102–104; CSF B cells are known to make lymphotoxin-α and TNF103,104 although data on GM-CSF and IL-6 are not available. These cytokines can modulate CNS damage and the immune response through several mechanisms summarized in Fig. 4.

Of note, TNF is expressed highly in cortical lesions associated with IFNγ59, particularly in those with B cell aggregates105. Bulk RNA sequencing of meningeal B cell aggregate-associated grey matter lesions suggest that an imbalance of TNF-mediated death signalling occurs through increased expression of TNFR1 (which induces cell death) over that of TNFR2 (which induces survival pathways)106. In EAE, forced expression or injection in the subarachnoid space of TNF and IFNγ leads to enhanced EAE induction characterized by a gradient of microglial cell activation and neuronal loss and associated with demyelination emanating away from cortical lesions105,107 reminiscent of MS. Temporally, TNF and IFNγ induce an initial expansion of inflammatory microglia that directly associate and phagocytose pre-synapse proteins108. Later, the microglial numbers contract to the density of healthy controls and microglia lose some of their inflammatory polarization, become more ramified and are associated with increased neuronal loss. Similar observations were made analysing cortical lesions of MS patients108. Of note, T-bet+ memory B cells can produce IFNγ12 and, thus, B cells could be self-sufficient in driving TNF-mediated and IFNγ-mediated CNS pathology.

The damage dealt by pro-inflammatory cytokines may be balanced by regulatory cytokines produced by Breg cells though several mechanisms (Fig. 4). Regulatory roles for B cells are exemplified in B cell-deficient or B cell-depleted mice that develop worse EAE than mice with full B cell repertoires109,110. The anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 (refs74,110,111), TGFβ1 (refs112,113) and IL-35 (ref.114) have all been found to be made by subsets of Breg cells in either EAE or MS. Additionally, Breg cells can also inhibit T cell responses through physical interactions using PD-L1 (ref.115). Although Breg cells modulate EAE, it is not clear whether these cells act in the periphery or within the CNS. In support of Breg cells working within the CNS, IL-10+ plasma cells are seen in active/mixed active–inactive MS lesions15 and IL-10 is inducible in some B cells from EAE spinal cords116. Moreover, in one EAE study, ~30% of B cells in meningeal B cell aggregates express mRNA for either IL-10 or IL-35 (ref.60). In contrast, others have found that large numbers of IL-10-producing plasmablasts are seen in lymph nodes that drain the site of immunization in EAE but IL-10-expressing B-lineage cells are not seen in the CNS of EAE111,117. Furthermore, preventing B cells from accessing these lymph nodes abolished the capacity of Breg cells to suppress EAE117. One population that clearly enters the CNS in MS and EAE are IL-10+ gut-derived IgA+ plasma cells that suppress EAE severity18,74. Thus, there is a clear role for regulatory B cells in MS but whether the primary site of inhibition is within the CNS or in the periphery remains unanswered.

B cell functions in other CNS disorders

The entry of B cell lymphomas into the CNS is sometimes associated with local damage but, more often, it is not associated with any damage, suggesting that the presence of B cells in the CNS, even in large numbers, is not necessarily enough to induce pathology22. Even when B cell lymphomas are associated with damage, it is likely that a prior insult to the CNS led to the upregulation of chemokines that promote B cell recruitment rather than the B cells being directly pathogenic22,81. Thus, B cell entry into the CNS is insufficient to induce CNS pathology, suggesting that a trigger is needed to convert B cells to an injurious state.

The most commonly studied mechanism for B cells to induce CNS damage is through the production of autoantibodies. An example of this is seen in NMO, where anti-AQP4 antibodies induce astrocyte death and destruction of CNS barriers by removing astrocyte endfeet1. Antibody deposition leads to complement deposition, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and enhanced T cell immunity. In MOG antibody-associated disorder, antibodies induce demyelination emanating away from blood vessels in affected tissues1. In lesions, antibodies are associated with complement deposition, complement-dependent cytotoxicity, macrophages containing myelin and T cells. In contrast to these more inflammatory disorders, anti-NMDAR encephalomyelitis is driven by IgG4 antibodies that are not associated with complement deposition or antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity but, instead, it is likely that these antibodies affect the crosslinking and internalization of NMDAR1. Thus, inflammation is not always required for B cells to be pathogenic. Autoantibody-driven pathology is also seen in patients with COVID-19. While virus-specific antibodies and BCRs are detected among plasma cells and B cells in CSF, many of these cells are also reactive against CNS antigens27. Thus, in addition to autoimmune diseases, viral infection can trigger secondary autoimmunity in the CNS.

Gaps of knowledge and new directions

We have discussed the diversity of B cells found in the brain in both health and disease as well as where to locate them. It is clear that B cells are present in the CNS in many disorders and that they affect disease outcomes. However, there are still many gaps in our understanding of precisely how these B cells contribute to disease and where B cells and plasma cells are located in the CNS during these conditions. Even in MS, where B cells have been studied in detail, there are remaining uncertainties regarding the localization of specific subsets of B cells in CNS lesions or whether particular B cell subsets exist in the CNS. Precisely which mechanisms B cells use to mediate CNS outcomes also remain unclear. Answers to these questions are needed to define which subsets of B cells should be targeted to overcome CNS pathology and which subsets confer benefits in the CNS.

In the context of MS, several mechanisms have been suggested to explain how B cells contribute to MS. Here, we have highlighted that B cells interact with T cells to promote T cell pathology and that several types of secreted B cell products, including cytokines, extracellular vesicles and antibodies, may all contribute to MS pathology. What is not clear is the degree to which these various mechanisms are active within the CNS versus the periphery and which subsets of B cells primarily use these disease mechanisms to promote pathology. It has also been noted that, while B cell infiltration into the CNS in MS is associated with CNS damage, this is not universally true of all CNS conditions22. Currently, it is not clear if there is a specific trigger that converts B cells into pathogenic entities or whether their diverse roles are simply due to the chronicity of conditions or other factors. It is also clear that the gut microbiome can regulate B cell functions in the CNS118 but this is poorly defined. A better understanding of how B cells differ in the various conditions discussed herein would be of great benefit to understand the mechanisms that B cells use to promote neurodegeneration or neuroprotection and could potentially unlock needed therapeutic targets.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

R.W.J. acknowledges postdoctoral fellowship funding from the University of Calgary Eyes High program, the Multiple Sclerosis of Canada and Roche unrestricted educational fellowship. V.W.Y. acknowledges salary support from the Canada Research Chair Tier 1 program and operating grant support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada.

Glossary

- B1 B cells

A subset of mature B cells with limited B cell receptor diversity predominantly found within the peritoneal and pleural cavities that typically differentiates directly into plasma cells, forming few memory cells.

- Follicular B cells

A subset of mature B cells, also known as B2 B cells, that represents the majority of B cells in the body and are commonly found within all lymphoid organs.

- Marginal zone B cells

A subset of mature B cells with limited B cell receptor diversity that is predominantly found in the marginal zone of the spleen and which typically differentiates directly into plasma cells but can also generate memory cells.

- Germinal centre B cells

This subset of activated B cells is an intermediate stage of differentiation and is the precursor of higher-affinity memory B cells and plasma cells.

- Memory B cells

A subset of B cells that is antigen experienced and has reacquired a quiescent phenotype and can participate in secondary immune responses, or sometimes refers to activated B cells that retain an activated phenotype.

- T-bet+ memory B cells

A subset of memory B cells that expresses the transcription factor T-bet whose numbers tend to increase with age as well as in autoimmune disorders and viral infections.

- Plasma cells

Terminally differentiated B cells that produce large amounts of antibodies and are short-lived unless they find a survival niche allowing long-term maintenance.

- Regulatory B (Breg) cells

This subset of B cells suppresses inflammation through the secretion of anti-inflammatory proteins or through physical interactions.

- Plasmablasts

The precursor to plasma cells that has begun to produce antibodies but also retains some features of B cells, such as surface B cell receptor and MHC class II expression, and is still proliferating.

- T helper 17 (TH17) cells

A subset of CD4+ T cells characterized by the expression of the transcription factor RORγT and the expression of IL-17A that is commonly associated with immunity against extracellular pathogens.

- T follicular helper cells

A subset of CD4+ T cells characterized by the expression of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6 and the chemokine receptor CXCR5 allowing these cells to co-localize with B cells and promote their differentiation through physical interactions.

- T helper 1 (TH1) cells

A subset of CD4+ T cells characterized by the expression of the transcription factor T-bet and the expression of IFNγ that is commonly associated with cellular immunity.

Author contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Immunology thanks S. Pillai and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41577-021-00652-6.

References

- 1.Sabatino JJ, Jr., Probstel AK, Zamvil SS. B cells in autoimmune and neurodegenerative central nervous system diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019;20:728–745. doi: 10.1038/s41583-019-0233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilden DH. Infectious causes of multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:195–202. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70023-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li R, Patterson KR, Bar-Or A. Reassessing B cell contributions in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:696–707. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akkaya M, Kwak K, Pierce SK. B cell memory: building two walls of protection against pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:229–238. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0244-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang TH, Jung ST. Boosting therapeutic potency of antibodies by taming Fc domain functions. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019;51:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0345-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korn T, Kallies A. T cell responses in the central nervous system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017;17:179–194. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rua R, McGavern DB. Advances in meningeal immunity. Trends Mol. Med. 2018;24:542–559. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agrawal SM, et al. Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer shows active perivascular cuffs in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2013;136:1760–1777. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korin B, et al. High-dimensional, single-cell characterization of the brain’s immune compartment. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20:1300–1309. doi: 10.1038/nn.4610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brioschi S, et al. Heterogeneity of meningeal B cells reveals a lymphopoietic niche at the CNS borders. Science. 2021;373:eabf9277. doi: 10.1126/science.abf9277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schafflick D, et al. Single-cell profiling of CNS border compartment leukocytes reveals that B cells and their progenitors reside in non-diseased meninges. Nat. Neurosci. 2021;24:1225–1234. doi: 10.1038/s41593-021-00880-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubtsova K, Rubtsov AV, Cancro MP, Marrack P. Age-associated B cells: a T-bet-dependent effector with roles in protective and pathogenic immunity. J. Immunol. 2015;195:1933–1937. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzpatrick Z, et al. Gut-educated IgA plasma cells defend the meningeal venous sinuses. Nature. 2020;587:472–476. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2886-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frischer JM, et al. The relation between inflammation and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis brains. Brain. 2009;132:1175–1189. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Machado-Santos J, et al. The compartmentalized inflammatory response in the multiple sclerosis brain is composed of tissue-resident CD8+ T lymphocytes and B cells. Brain. 2018;141:2066–2082. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howell OW, et al. Meningeal inflammation is widespread and linked to cortical pathology in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2011;134:2755–2771. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prasad R. Immunoglobulin levels in serum and cerebrospinal fluid in certain viral infections of the central nervous system. J. Infect. Dis. 1983;148:607. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Probstel AK, et al. Gut microbiota-specific IgA+ B cells traffic to the CNS in active multiple sclerosis. Sci. Immunol. 2020;5:eabc7191. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abc7191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korin B, et al. Short-term sleep deprivation in mice induces B cell migration to the brain compartment. Sleep. 2020;43:zsz222. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kmiecik J, et al. Elevated CD3+ and CD8+ tumor-infiltrating immune cells correlate with prolonged survival in glioblastoma patients despite integrated immunosuppressive mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment and at the systemic level. J. Neuroimmunol. 2013;264:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Domingues PH, et al. Immunophenotypic identification and characterization of tumor cells and infiltrating cell populations in meningiomas. Am. J. Pathol. 2012;181:1749–1761. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuhlmann T, Lassmann H, Bruck W. Diagnosis of inflammatory demyelination in biopsy specimens: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115:275–287. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0320-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han S, et al. Glioma cell-derived placental growth factor induces regulatory B cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014;57:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee-Chang C, et al. Activation of 4-1BBL+ B cells with CD40 agonism and IFNgamma elicits potent immunity against glioblastoma. J. Exp. Med. 2021;218:e20200913. doi: 10.1084/jem.20200913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matschke J, et al. Neuropathology of patients with COVID-19 in Germany: a post-mortem case series. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:919–929. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30308-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heming M, et al. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19 feature T cell exhaustion and dedifferentiated monocytes in cerebrospinal fluid. Immunity. 2021;54:164–175.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song E, et al. Divergent and self-reactive immune responses in the CNS of COVID-19 patients with neurological symptoms. Cell Rep. Med. 2021;2:100288. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khateb M, Bosak N, Muqary M. Coronaviruses and central nervous system manifestations. Front. Neurol. 2020;11:715. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phares TW, DiSano KD, Stohlman SA, Bergmann CC. Progression from IgD+ IgM+ to isotype-switched B cells is site specific during coronavirus-induced encephalomyelitis. J. Virol. 2014;88:8853–8867. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00861-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tschen SI, et al. CNS viral infection diverts homing of antibody-secreting cells from lymphoid organs to the CNS. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006;36:603–612. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiSano KD, Stohlman SA, Bergmann CC. Activated GL7+ B cells are maintained within the inflamed CNS in the absence of follicle formation during viral encephalomyelitis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017;60:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cepok S, et al. Short-lived plasma blasts are the main B cell effector subset during the course of multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2005;128:1667–1676. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kowarik MC, et al. CXCL13 is the major determinant for B cell recruitment to the CSF during neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:93. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stock AD, et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures in the choroid plexus in neuropsychiatric lupus. JCI Insight. 2019;4:e124203. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.124203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mok MY, Chan EY, Wong WS, Lau CS. Intrathecal immunoglobulin production in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with neuropsychiatric manifestations. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2007;66:846–847. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.061069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kowarik MC, et al. The cerebrospinal fluid immunoglobulin transcriptome and proteome in neuromyelitis optica reveals central nervous system-specific B cell populations. J. Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:19. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0240-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malviya M, et al. NMDAR encephalitis: passive transfer from man to mouse by a recombinant antibody. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2017;4:768–783. doi: 10.1002/acn3.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jelcic I, et al. Memory B cells activate brain-homing, autoreactive CD4+ T cells in multiple sclerosis. Cell. 2018;175:85–100.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuhlmann T, et al. An updated histological classification system for multiple sclerosis lesions. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;133:13–24. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1653-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bell L, Lenhart A, Rosenwald A, Monoranu CM, Berberich-Siebelt F. Lymphoid aggregates in the CNS of progressive multiple sclerosis patients lack regulatory T cells. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:3090. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi SR, et al. Meningeal inflammation plays a role in the pathology of primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2012;135:2925–2937. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reali C, et al. B cell rich meningeal inflammation associates with increased spinal cord pathology in multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 2020;30:779–793. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Monaco S, Nicholas R, Reynolds R, Magliozzi R. Intrathecal inflammation in progressive multiple sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:8217. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corcione A, et al. Recapitulation of B cell differentiation in the central nervous system of patients with multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11064–11069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402455101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schafflick D, et al. Integrated single cell analysis of blood and cerebrospinal fluid leukocytes in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:247. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14118-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramesh A, et al. A pathogenic and clonally expanded B cell transcriptome in active multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:22932–22943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2008523117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Pauli F, et al. Features of intrathecal immunoglobulins in patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2010;288:147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eggers EL, et al. Clonal relationships of CSF B cells in treatment-naive multiple sclerosis patients. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e92724. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.92724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munoz U, et al. Main role of antibodies in demyelination and axonal damage in multiple sclerosis. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10571-021-01059-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fransen NL, et al. Absence of B cells in brainstem and white matter lesions associates with less severe disease and absence of oligoclonal bands in MS. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2021;8:e955. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Absinta M, et al. Gadolinium-based MRI characterization of leptomeningeal inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015;85:18–28. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Magliozzi R, et al. Meningeal B-cell follicles in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis associate with early onset of disease and severe cortical pathology. Brain. 2007;130:1089–1104. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cepok S, et al. Patterns of cerebrospinal fluid pathology correlate with disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2001;124:2169–2176. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.11.2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Magliozzi R, et al. A Gradient of neuronal loss and meningeal inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2010;68:477–493. doi: 10.1002/ana.22230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Howell OW, et al. Extensive grey matter pathology in the cerebellum in multiple sclerosis is linked to inflammation in the subarachnoid space. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2015;41:798–813. doi: 10.1111/nan.12199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lovato L, et al. Related B cell clones populate the meninges and parenchyma of patients with multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2011;134:534–541. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lucchinetti CF, et al. Inflammatory cortical demyelination in early multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:2188–2197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peterson JW, Bo L, Mork S, Chang A, Trapp BD. Transected neurites, apoptotic neurons, and reduced inflammation in cortical multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann. Neurol. 2001;50:389–400. doi: 10.1002/ana.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Magliozzi R, et al. Inflammatory intrathecal profiles and cortical damage in multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2018;83:739–755. doi: 10.1002/ana.25197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mitsdorffer M, et al. Formation and immunomodulatory function of meningeal B-cell aggregates in progressive CNS autoimmunity. Brain. 2021;144:1697–1710. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pikor NB, et al. Integration of Th17- and lymphotoxin-derived signals initiates meningeal-resident stromal cell remodeling to propagate neuroinflammation. Immunity. 2015;43:1160–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grewal IS, et al. CD62L is required on effector cells for local interactions in the CNS to cause myelin damage in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Immunity. 2001;14:291–302. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dang AK, Tesfagiorgis Y, Jain RW, Craig HC, Kerfoot SM. Meningeal infiltration of the spinal cord by non-classically activated B cells is associated with chronic disease course in a spontaneous B cell-dependent model of CNS autoimmune disease. Front. Immunol. 2015;6:470. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Serafini B, Rosicarelli B, Magliozzi R, Stigliano E, Aloisi F. Detection of ectopic B-cell follicles with germinal centers in the meninges of patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 2004;14:164–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Michel L, et al. Activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule regulates B lymphocyte migration across central nervous system barriers. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019;11:eaaw0475. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alter A, et al. Determinants of human B cell migration across brain endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 2003;170:4497–4505. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haas J, et al. The choroid plexus is permissive for a preactivated antigen-experienced memory B-cell subset in multiple sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:618544. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.618544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van Langelaar J, et al. Induction of brain-infiltrating T-bet-expressing B cells in multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2019;86:264–278. doi: 10.1002/ana.25508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hussain RZ, et al. alpha4-integrin deficiency in B cells does not affect disease in a T-cell-mediated EAE disease model. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2019;6:e563. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lehmann-Horn K, Sagan SA, Bernard CC, Sobel RA, Zamvil SS. B-cell very late antigen-4 deficiency reduces leukocyte recruitment and susceptibility to central nervous system autoimmunity. Ann. Neurol. 2015;77:902–908. doi: 10.1002/ana.24387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hausler D, et al. CNS inflammation after natalizumab therapy for multiple sclerosis: A retrospective histopathological and CSF cohort study. Brain Pathol. 2021;31:e12969. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tesfagiorgis Y, Zhu SL, Jain R, Kerfoot SM. Activated B cells participating in the anti-myelin response are excluded from the inflamed central nervous system in a model of autoimmunity that allows for B cell recognition of autoantigen. J. Immunol. 2017;199:449–457. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1602042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pollok K, et al. The chronically inflamed central nervous system provides niches for long-lived plasma cells. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2017;5:88. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0487-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rojas OL, et al. Recirculating Intestinal IgA-producing cells regulate neuroinflammation via IL-10. Cell. 2019;176:610–624.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nguyen DC, et al. Factors of the bone marrow microniche that support human plasma cell survival and immunoglobulin secretion. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3698. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05853-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baker D, Pryce G, James LK, Schmierer K, Giovannoni G. Failed B cell survival factor trials support the importance of memory B cells in multiple sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020;27:221–228. doi: 10.1111/ene.14105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Touil H, et al. Human central nervous system astrocytes support survival and activation of B cells: implications for MS pathogenesis. J. Neuroinflammation. 2018;15:114. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1136-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chan TD, et al. Antigen affinity controls rapid T-dependent antibody production by driving the expansion rather than the differentiation or extrafollicular migration of early plasmablasts. J. Immunol. 2009;183:3139–3149. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Quinn JL, Kumar G, Agasing A, Ko RM, Axtell RC. Role of TFH cells in promoting T helper 17-induced neuroinflammation. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:382. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chihara N, et al. Plasmablasts as migratory IgG-producing cells in the pathogenesis of neuromyelitis optica. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.O’Connor T, et al. Age-related gliosis promotes central nervous system lymphoma through CCL19-mediated tumor cell retention. Cancer Cell. 2019;36:250–267.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Williams MT, et al. Interleukin-15 enhances cellular proliferation and upregulates CNS homing molecules in pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2014;123:3116–3127. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-499970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Krumbholz M, et al. BAFF is produced by astrocytes and up-regulated in multiple sclerosis lesions and primary central nervous system lymphoma. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:195–200. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.DiSano KD, Royce DB, Gilli F, Pachner AR. Central nervous system inflammatory aggregates in the Theiler’s virus model of progressive multiple sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1821. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hohlfeld R, Dornmair K, Meinl E, Wekerle H. The search for the target antigens of multiple sclerosis, part 2: CD8+ T cells, B cells, and antibodies in the focus of reverse-translational research. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:317–331. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lucchinetti C, et al. Heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis lesions: implications for the pathogenesis of demyelination. Ann. Neurol. 2000;47:707–717. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200006)47:6<707::AID-ANA3>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sadaba MC, et al. Axonal and oligodendrocyte-localized IgM and IgG deposits in MS lesions. J. Neuroimmunol. 2012;247:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Genain CP, Cannella B, Hauser SL, Raine CS. Identification of autoantibodies associated with myelin damage in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Med. 1999;5:170–175. doi: 10.1038/5532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang Y, et al. Clonal expansion of IgA-positive plasma cells and axon-reactive antibodies in MS lesions. J. Neuroimmunol. 2005;167:120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Keegan M, et al. Relation between humoral pathological changes in multiple sclerosis and response to therapeutic plasma exchange. Lancet. 2005;366:579–582. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Silber E, Semra YK, Gregson NA, Sharief MK. Patients with progressive multiple sclerosis have elevated antibodies to neurofilament subunit. Neurology. 2002;58:1372–1381. doi: 10.1212/WNL.58.9.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Blauth K, et al. Antibodies produced by clonally expanded plasma cells in multiple sclerosis cerebrospinal fluid cause demyelination of spinal cord explants. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130:765–781. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1500-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brandle SM, et al. Distinct oligoclonal band antibodies in multiple sclerosis recognize ubiquitous self-proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:7864–7869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522730113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Willis SN, et al. Investigating the antigen specificity of multiple sclerosis central nervous system-derived immunoglobulins. Front. Immunol. 2015;6:600. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Benjamins JA, et al. Exosome-enriched fractions from MS B cells induce oligodendrocyte death. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2019;6:e550. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lisak RP, et al. B cells from patients with multiple sclerosis induce cell death via apoptosis in neurons in vitro. J. Neuroimmunol. 2017;309:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bettelli E, Baeten D, Jager A, Sobel RA, Kuchroo VK. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-specific T and B cells cooperate to induce a Devic-like disease in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:2393–2402. doi: 10.1172/JCI28334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kuerten S, et al. Tertiary lymphoid organ development coincides with determinant spreading of the myelin-specific T cell response. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:861–873. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Parker Harp CR, et al. B cells are capable of independently eliciting rapid reactivation of encephalitogenic CD4 T cells in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0199694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pierson ER, Stromnes IM, Goverman JM. B cells promote induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by facilitating reactivation of T cells in the central nervous system. J. Immunol. 2014;192:929–939. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Claes N, et al. Age-associated B cells with proinflammatory characteristics are expanded in a proportion of multiple sclerosis patients. J. Immunol. 2016;197:4576–4583. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li R, et al. Proinflammatory GM-CSF-producing B cells in multiple sclerosis and B cell depletion therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7:310ra166. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab4176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.McWilliam O, Sellebjerg F, Marquart HV, von Essen MR. B cells from patients with multiple sclerosis have a pathogenic phenotype and increased LTα and TGFβ1 response. J. Neuroimmunol. 2018;324:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stein J, et al. Intrathecal B cells in ms have significantly greater lymphangiogenic potential compared to B cells derived from non-MS subjects. Front. Neurol. 2018;9:554. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gardner C, et al. Cortical grey matter demyelination can be induced by elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines in the subarachnoid space of MOG-immunized rats. Brain. 2013;136:3596–3608. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Magliozzi R, et al. Meningeal inflammation changes the balance of TNF signalling in cortical grey matter in multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroinflammation. 2019;16:259. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1650-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.James RE, et al. Persistent elevation of intrathecal pro-inflammatory cytokines leads to multiple sclerosis-like cortical demyelination and neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020;8:66. doi: 10.1186/s40478-020-00938-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.van Olst L, et al. Meningeal inflammation in multiple sclerosis induces phenotypic changes in cortical microglia that differentially associate with neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2021;141:881–899. doi: 10.1007/s00401-021-02293-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fehres CM, et al. APRIL induces a novel subset of IgA+ regulatory B cells that suppress inflammation via expression of IL-10 and PD-L1. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1368. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fillatreau S, Sweenie CH, McGeachy MJ, Gray D, Anderton SM. B cells regulate autoimmunity by provision of IL-10. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:944–950. doi: 10.1038/ni833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pennati A, et al. Regulatory B cells induce formation of IL-10-expressing T cells in mice with autoimmune neuroinflammation. J. Neurosci. 2016;36:12598–12610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1994-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bjarnadottir K, et al. B cell-derived transforming growth factor-beta1 expression limits the induction phase of autoimmune neuroinflammation. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34594. doi: 10.1038/srep34594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Piancone F, et al. B lymphocytes in multiple sclerosis: Bregs and BTLA/CD272 expressing-CD19+ lymphocytes modulate disease severity. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:29699. doi: 10.1038/srep29699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Shen P, et al. IL-35-producing B cells are critical regulators of immunity during autoimmune and infectious diseases. Nature. 2014;507:366–370. doi: 10.1038/nature12979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Khan AR, et al. PD-L1hi B cells are critical regulators of humoral immunity. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:5997. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lehmann-Horn K, et al. CNS accumulation of regulatory B cells is VLA-4-dependent. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2016;3:e212. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]