Abstract

Hyperuricemia is related to an increased risk of cardiovascular events from a meta-analysis and antihyperuricemia agents may influence to cardiac function. We evaluated the effect of febuxostat on echocardiographic parameters of diastolic function in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia as a prespecified endpoint in the subanalysis of the PRIZE study. Patients in the PRIZE study were assigned randomly to either add-on febuxostat treatment group or control group with only appropriate lifestyle modification. Of the 514 patients in the overall study, 65 patients (31 in the febuxostat group and 34 in the control group) who had complete follow-up echocardiographic data of the ratio of peak early diastolic transmitral flow velocity (E) to peak early diastolic mitral annular velocity (e′) at baseline and after 12 and 24 months were included. The primary endpoint was a comparison of the changes in the E/e′ between the two groups from baseline to 24 months. Interestingly, e′ was slightly decreased in the control group compared with in the febuxostat group (treatment p = 0.068, time, p = 0.337, treatment × Time, p = 0.217). As a result, there were significant increases in E/e′ (treatment p = 0.045, time, p = 0.177, treatment × time, p = 0.137) after 24 months in the control group compared with the febuxostat group. There was no significant difference in the serum levels of N-terminal-pro brain natriuretic peptide and high-sensitive troponin I between the two groups during the study period. In conclusions, additional febuxostat treatment in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia for 24 months might have a potential of preventable effects on the impaired diastolic dysfunction.

Keywords: febuxostat, hyperuricemia, echocardiography, diastolic function, NT-proBNP

Introduction

Hyperuricemia can be associated with cardiometabolic abnormalities and the association leads to the development of atherosclerosis and resultant cardiovascular disease [1–3]. Several studies investigated the association between hyperuricemia and echocardiographic variables [4–7]. Krishnan et al. showed the correlation between the left ventricular (LV) mass index and serum uric acid (SUA) level [8]. In addition, Lin et al. also showed the LV diastolic functional parameters were associated with gout [9]. The association between hyperuricemia and cardiac function is a key mechanism of hyperuricemia on cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, it is clinically required to evaluate the impact of antihyperuricemia agents on cardiac function from the randomized cohort study.

Febuxostat is a nonpurine selective inhibitor of xanthine oxidase for the treatment of hyperuricemia and gout. Febuxostat has greater potency for inhibition of xanthine oxidase activity and more urate-lowering efficacy than allopurinol. Accordingly, febuxostat may have superior antioxidative and antiatherogenic effects to allopurinol [10, 11]. According to the link between hyperuricemia and cardiac function, we hypothesized that the febuxostat can influence the LV diastolic function in patients with hyperuricemia. The PRIZE (program of vascular evaluation under uric acid control by xanthine oxidase inhibitor, febuxostat: multicenter, randomized controlled) study (University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trial Registry UMIN000012911) was a prospective multicenter study conducted in Japanese patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia to evaluate the inhibitory effect of febuxostat on the progression of atherosclerosis based on carotid-artery intima-media thickness assessed by ultrasonography over a 2-year follow-up period [12]. To elucidate the effect of febuxostat on echocardiographic parameters, we investigated the effect of the febuxostat on 2-dimensional and Doppler echocardiographic parameters and biomarkers from baseline to 24 months as a prespecified endpoint in the subanalysis of the PRIZE study (University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trial Registry UMIN000041322).

Study design

Details of the PRIZE study design and inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study have been published elsewhere [13]. In brief, the study was a multicenter, randomized, prospective, open-label, blinded-endpoint trial accomplished by 48 sites throughout Japan. A total of 514 adults (aged ≥20 years) who had hyperuricemia with SUA > 7.0 mg/dL enrolled in this study between May 2014 and August 2018. Key exclusion criteria were the administration of any SUA-lowering agents within the 8-week period prior to the assessment of eligibility, the presence of gouty tophus, or symptoms of gout arthritis within one year before assessment of eligibility. The patients were randomly assigned using a 1:1 ratio to either add-on febuxostat treatment (febuxostat group, n = 257) or an appropriate lifestyle modification for hyperuricemia, such as healthy diet and exercise therapy without febuxostat (control group, n = 257). The original primary endpoint of the PRIZE study was the change in mean common carotid IMT 24 months after treatment randomization. We prespecified the echocardiographic endpoint in the subanalysis of the PRIZE study. Echocardiography was performed as an ad hoc examination at baseline and 12 and 24 months after treatment randomization. The ethical committees of each participating institution approved the study protocol, with written informed consent for participation in the study being obtained from all subjects.

Study population

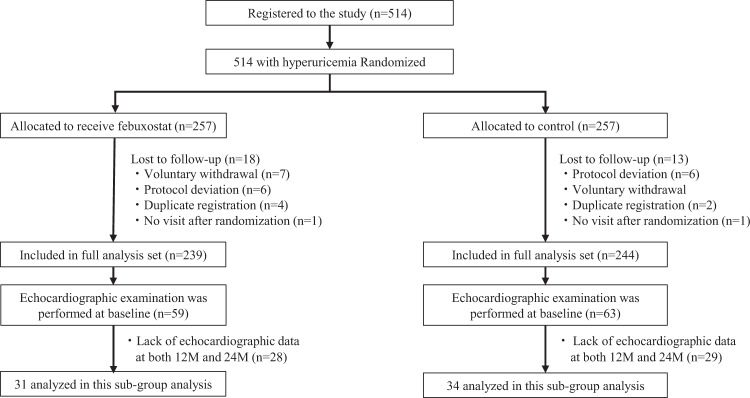

The echocardiographic examination was performed in 59 patients in the febuxostat group and in 63 patients in the control group at the baseline. We excluded the patients with the lack of echocardiographic data at both 12 and 24 months to analyze the changes of echocardiographic parameters during follow-up. After exclusions, 31 patients in the febuxostat group and in 34 patients in the control group were included for the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient selection

Echocardiographic assessment

Echocardiography was performed by the commercially available ultrasound machine and various hemodynamic parameters were measured at each institution. The recordings and measurements were according to the guidelines issued by American Society of Echocardiography [14]. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and left atrial volume were measured and calculated from the apical two- and four-chamber view using bi-plane disk methods. LV mass by M-mode echocardiography was derived using the American Society of Echocardiography’s guideline formula. Transmitral flow velocity was recorded from the apical long-axis or four-chamber view. The peak early diastolic (E) and the peak atrial systolic (A) velocities, and deceleration time of early TMF velocity were measured. The mitral annular motion velocity pattern was recorded from the apical four-chamber view with a sample volume placed at the lateral or septal side of the mitral annulus using pulsed tissue Doppler echocardiography. Early diastolic (e′) peak velocities were measured and the ratio of E to e′ (E/e′) was calculated using averaged values. This index was used to be a marker of LV filling pressure.

Laboratory examination

Blood samples were collected at baseline and after 12 and 24 months. The serum levels of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and high-sensitive troponin I were measured in a centralized laboratory (SRL Co. Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

For the baseline variables, the summary statistics were expressed as frequencies and proportions for categorical data and mean (SD) or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables. Mean percentage changes in the echocardiographic variables and laboratory parameters from baseline to 12 and 24 months and its 95% confidence interval (CI), estimated with the repeated measures regression model using the mixed-effect model. To assess change from the baseline in the model with the logarithmic the echocardiographic variables, the baseline logarithmic variable was further adjusted in the model. Comparisons of changes in the other efficacy endpoints between the treatment groups were performed by examining the interaction between the treatment groups and follow-up time, which statistical tests for differences in rates of change between the regression slopes of the weight over time between the febuxostat group and control group. All P values were two-sided with a level of significance of 0.05, and there were adjustments for baseline data. We were unable to adjust for the other variables in this analysis due to the limited number of patients. All statistical analyses were performed using R 4.0.1. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.)

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics

Comparisons of baseline clinical characteristics of the febuxostat group and control group were shown in Table 1. In the febuxostat group, 25.8% of the patients received 10 mg, 22.6% received 20 mg, and 48.4% received 40 mg daily as the final dose of febuxostat. While around 90% of the subjects had hypertension in the two groups, the blood pressure was well controlled in both groups. Dyslipidemia also existed in around 60% of the patients in each group; however, the average serum total cholesterol level was within the normal range. There was no significant difference in any examined variable between the two groups at baseline except the estimated glomerular filtration rate which was slightly higher in the control group than in the febuxostat group (p = 0.020). The uric acid level was significantly lower in the control group (p = 0.031). Table 2 showed the baseline echocardiographic variables in both groups. At baseline, averaged e′ in febuxostat group was lower and E/e’ in the febuxostat group was higher than in the control group. There was no significant difference in the other variables between the two groups. Around 70% patients had normal or concentric remodeling LV geometry.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics at baseline

| ALL | Control | Febuxostat | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 65 | 34 | 31 | |

| Clinical background | ||||

| Age, year | 71 [63,77] | 71 [63,77] | 71 [63,77] | 1.000 |

| Male, % | 80 (52) | 88 (30) | 71 (22) | 0.082 |

| Body mass index | 25.1 [22.2, 26.9] | 25.6 [22.9, 27.4] | 24.7 [22.1, 26.4] | 0.482 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 128 [118, 133] | 128 [120, 132] | 126 [115, 133] | 0.818 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 72 [66,80] | 77 [68,80] | 72 [65,79] | 0.252 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 62 [58,72] | 63 [56,71] | 62 [59,72] | 0.555 |

| Clinical history | ||||

| Smoker, %, (n) | 55.4 (36) | 64.7 (22) | 45.2 (14) | 0.113 |

| Hypertension, %, (n) | 90.8 (59) | 88.2 (30) | 93.5 (29) | 0.460 |

| Diabetes mellitus, %, (n) | 41.5 (27) | 38.2 (13) | 45.2 (14) | 0.571 |

| Dyslipidemia, %, (n) | 63.1 (41) | 55.9 (19) | 71.0 (22) | 0.208 |

| Myocardial infarction, %, (n) | 13.8 (9) | 8.8 (3) | 19.4 (6) | 0.220 |

| PCI, %, (n) | 24.6 (16) | 17.6 (6) | 32.3 (10) | 0.172 |

| CABG, %, (n) | 6.2 (4) | 5.9 (2) | 6.5 (2) | 0.924 |

| Stroke, %, (n) | 4.6 (3) | 5.9 (2) | 3.2 (1) | 0.610 |

| Heart failure, %, (n) | 16.9 (11) | 8.8 (3) | 25.8 (8) | 0.068 |

| Medications | ||||

| ARB %, (n) | 61.5 (40) | 58.8 (20) | 64.5 (20) | 0.638 |

| ACEI %, (n) | 12.8 (8) | 11.8 (4) | 12.9 (4) | 0.889 |

| Beta blocker %, (n) | 44.6 (29) | 45.1 (15) | 45.2 (14) | 0.933 |

| Diuretic %, (n) | 33.8 (22) | 32.4 (11) | 35.5 (11) | 0.790 |

| Statin %, (n) | 47.7 (31) | 44.1 (15) | 51.6 (16) | 0.610 |

| Anti-platelet %, (n) | 47.7 (31) | 50.0 (17) | 45.2 (14) | 0.696 |

| Aspirin %, (n) | 41.5 (27) | 38.2 (13) | 45.2 (14) | 0.571 |

| Laboratory Data | ||||

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.56 [4.01, 5.25] | 4.55 [4.16, 5.25] | 4.58 [3.98, 5.31] | 0.968 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 57.5 [47.0, 66.8] | 60.1 [53.2, 68.9] | 48.4 [42.5, 59.7] | 0.020 |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 7.65 [7.10, 8.28] | 7.50 [7.10, 7.90] | 8.10 [7.35, 8.70] | 0.031 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 99.5 [33.3, 314.1] | 98.7 [33.3, 222.4] | 100.4 [37.3, 361.4] | 0.624 |

| Troponin I, pg/mL | 5.15 [3.20, 9.70] | 5.10 [3.30, 8.00] | 5.30 [3.15, 10.55] | 0.867 |

BP blood pressure, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, ACEi angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ARB angiotensin II receptor blocker, eGFR estimate glomerular filtration rate, NT-proBNP N-terminal-pro brain natriuretic peptide.

Data are presented as the number of patients (percentage), mean ± SD or median (interquartile range).

Table 2.

Echocardiographic variables at baseline

| ALL | Control | Febuxostat | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 65 | 34 | 31 | |

| Echocardiographic variables | ||||

| TMF-E | 66 [57,80] | 64 [57,80] | 66 [58,81] | 0.480 |

| Averaged e’ | 7.65 [6.25, 9.10] | 7.75 [6.95, 10.20] | 6.09 [4.80, 7.99] | 0.028 |

| Averaged E/e’ | 8.04 [7.01, 10.01] | 7.90 [6.32, 9.08] | 9.18 [7.86, 11.67] | 0.032 |

| TMF-A | 79 [67,91] | 83 [69,93] | 74 [66,89] | 0.430 |

| E/A | 0.79 [0.74, 1.11] | 0.77 [0.69, 1.13] | 0.86 [0.76, 1.08] | 0.302 |

| Deceleration time | 217 [192, 241] | 220 [200, 247] | 210 [186, 234] | 0.349 |

| LV end-diastolic dimension | 48.0 [45.0, 52.0] | 48.2 [44.9, 52.3] | 47.0 [45.0, 52.0] | 0.804 |

| LV end-systolic dimension | 30.1 [27.7, 34.1] | 31.0 [27.7, 34.0] | 30.0 [27.8, 36.3] | 0.946 |

| LV ejection fraction | 63.9 [56.4, 69.0] | 64.0 [58.5, 69.0] | 63.0 [56.4, 69.0] | 0.602 |

| LV mass index | 101 [88, 123] | 102 [86, 121] | 99 [91, 128] | 0.611 |

| Categories of LV hypertrophy | 0.774 | |||

| Normal | 42.9% | 47.6% | 38.1% | |

| Concentric remodeling | 31.0% | 23.8% | 38.1% | |

| Concentric hypertrophy | 11.9% | 14.3% | 9.5% | |

| Eccentric hypertrophy | 14.3% | 14.3% | 14.3% | |

| LA volume | 58 [45,77] | 59 [42,77] | 54 [49,70] | 0.923 |

TMF-E early diastolic transmitral flow wave, e’ early mitral annular velocity, TMF-A late diastolic transmitral flow wave, LV left ventricular, LA, left atrial.

Data are presented as median (interquartile range).

Laboratory data

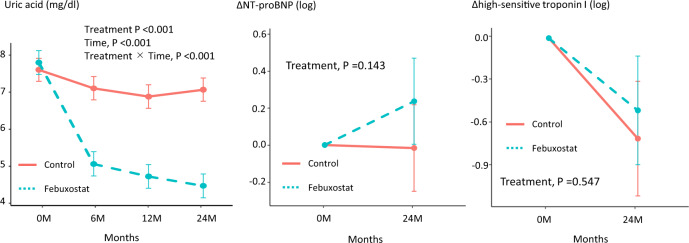

Figure 2 showed the changes in laboratory data, including uric acid, NT-pro BNP, and high-sensitive troponin I. There were significant differences in the SUA levels between the treatment groups at 6, 12, and 24 months, and the final SUA levels were 4.46 and 7.07 mg/dL in the febuxostat and control groups, respectively (treatment, time and treatment × time, all p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in serum level of NT-pro BNP (treatment p = 0.1143) and high-sensitive troponin I (treatment p = 0.547) in both groups throughout this study.

Fig. 2.

Changes in uric acid, NT-pro BNP, and high-sensitive troponin I at 12 and 24 months in the two treatment groups

Echocardiographic parameters

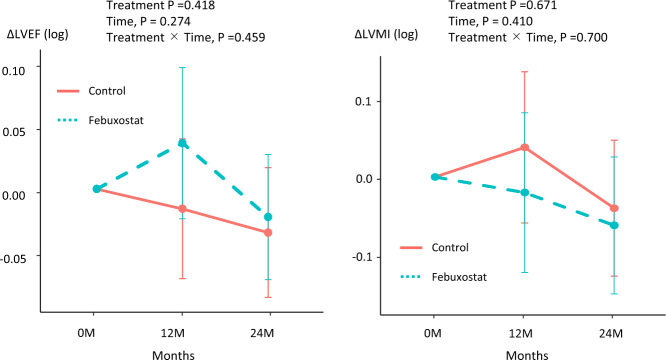

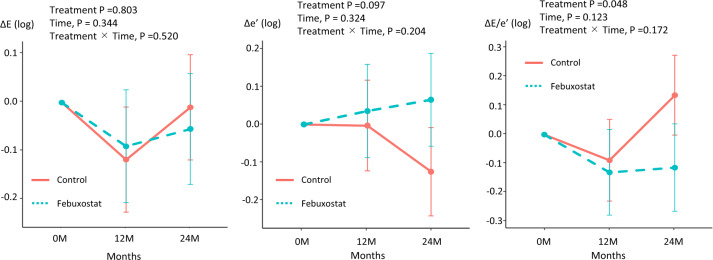

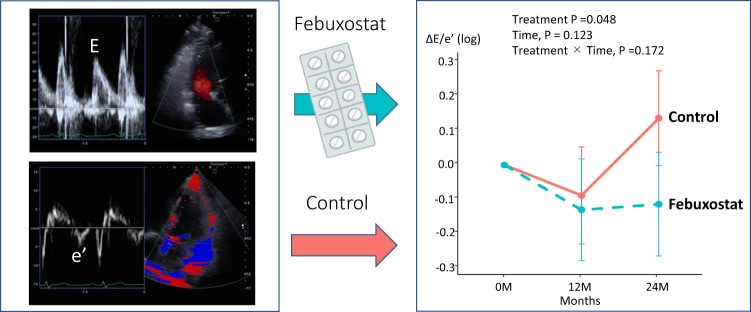

Comparisons of echocardiographic parameters at baseline and after 12 and 24 months of treatment in the febuxostat group and control group are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. There were no significant differences of LV ejection fraction (treatment p = 0.422, time, p = 0.283, treatment × Time, p = 0.469; Fig. 3) and LV mass index (treatment p = 0.713, time, p = 0.532, treatment × Time, p = 0.778; Fig. 3) at baseline and after 12 and 24 months in both groups. In the Doppler parameters, there were no significant difference of E wave (treatment p = 0.758, time, p = 0.325, treatment × Time, p = 0.486; Fig. 4) at baseline and after 12 and 24 months in both groups. Interestingly, e’ was slightly decreased in the control group compared with in the febuxostat group (treatment p = 0.068, time, p = 0.337, treatment × Time, p = 0.217; Fig. 4). As a result, there were significant difference between the control group and febuxostat group in E/e’ (treatment p = 0.045, time, p = 0.077, treatment × Time, p = 0.137; Fig. 4) after 24 months (control group 0.15 [0.001–0.291], febuxostat group -0.13 [-0.289–0.031], p = 0.010). We confirmed that there is no adverse effect of febuxostat on echocardiographic parameters and the febuxostat may lead to preventing the impaired diastolic dysfunction.

Fig. 3.

Changes in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and LV mass index (LVMI) at 12 and 24 months in the two treatment groups

Fig. 4.

Changes in early diastolic transmitral flow velocity (E), early diastolic mitral annular velocity (e’), and E/e’ at 12 and 24 months in the two treatment groups

Discussion

This study was a post hoc subgroup analysis of the PRIZE trial that focused on the effect of febuxostat on echocardiographic variables, including diastolic functional parameters. The key finding of the study was that the addition of febuxostat significantly prevented the worsen diastolic function (e’ and E/e′) compared to control group (Fig. 5). However, there is no significant differences of other parameters including LV mass index and LVEF between the two groups. Moreover, there is no significant differences in the biomarkers including NT-proBNP and high-sensitive troponin I. According to these results, it seems that febuxostat therapy may have a protective effect on cardiac diastolic function independent from LV morphological changes or biochemical changes. However, the present study should be considered as a proof of concept, and we believe that larger prospective multicenter studies using the advanced diastolic functional markers (e.g., strain imaging) are warranted to confirm the cardiovascular protective effects on diastolic function by febuxostat.

Fig. 5.

Graphical Abstract: This study was a post-hoc subgroup analysis of the PRIZE trial that focused on the effect of febuxostat on echocardiographic variables including diastolic functional parameters

Impact of febuxostat on systolic function

Elevated SUA has been shown to inhibit nitric oxide production by vascular endothelial cells and also to inhibit their proliferation and migration [15]. In the clinical trial, there are several observational studies and meta-analyses that described elevations of SUA as an independent marker of poor cardiac function, mortality, and poor exercise capacity [16–18]. Increased SUA levels might lead to the echocardiographic abnormalities through impacts on endothelial function and inflammation. Thus, SUA may represent not only an actual prognostic marker of cardiovascular diseases but also a potential target for intervention to treat cardiac function. Several investigators have shown that LV systolic function, such as LVEF and LV mass, improved by treatment of elevated SUA [8, 19]. Our results did not show results consistent with these previous results for the positive effects on LV systolic function. Our data showed that there are no significant differences of LVEF and LV mass between the two groups. One possible explanation was that the baseline LVEF and LV mass were completely within the normal range, then no change occurred during follow-up. We need a prospective randomized study for advanced HF. Another difference between our study and previous studies was that our control subjects underwent only appropriate lifestyle modifications for hyperuricemia.

Impact of febuxostat on diastolic function

In this study, additional treatment of febuxostat to usual hyperuricemia treatment significantly decreased the annual drop of e′ and elevation of E/e′, suggesting a preventive effect of febuxostat on LV compliance and diastolic dysfunction. The index of diastolic function is gradually decreased in aging. From the data of reference values, e′ decreases by 0.1 cm/sec per year [20]. In the control group, the e′ decreased from 8.5 to 7.7 after 2 years. Thus, there may be a decrease in diastolic function beyond age in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia.

Febuxostat treatment did not influence LV systolic functional parameters and cardiac structures or biomarkers, such as NT-proBNP. Some basic studies showed that treatment of SUA decreased myocardial indices of oxidative stress, as well as cardiac tissue xanthine oxidase highlights the potential direct antioxidant effects of the treatment of SUA compound as well as its uric acid and tissue xanthine oxidase lowering properties [21]. Additionally, our study population was consisted of 80% of all subjects in hypertension. Hyperuricemia is well known to be associated with LV hypertrophy and LV diastolic dysfunction in hypertensive patients [22, 23]. Hyperuricemia is associated with hypertensive heart disease, and hyperuricemia has an increased risk of coronary or cerebrovascular disease compared to hypertensive patients without hyperuricemia [24]. For these reasons, the protective effects on LV diastolic dysfunction have been detected in our cohort. However, in our data, the mechanisms for preventive effects of febuxostat on diastolic function were not fully explained. This study period may not have been long enough to assess the benefits of febuxostat. Moreover, the treatment effects of febuxostat might be stronger in patients with advanced HF than in patients with relatively normal cardiac function.

One possible mechanism is that the elevation in serum uric acid could be a reflection of increased xanthine oxidase activity, resulting in abnormal energy metabolism in cardiomyocytes [25]. This pathway might play an important role in diastolic dysfunction. Furthermore, increased activity of xanthine oxidase causes the release of free radicals and increased oxidative stress [26]. Oxidative stress lead to the pathogenesis of diastolic dysfunction. Because the precise mechanisms by which febuxostat treatment suppressed the increase in the diastolic parameter are not confirmed in our study, both basic and clinical data should be assessed in further studies.

Previous studies showed a J-curve association between uric acid and aortic diseases, including hypertension and low levels of SUA might be associated with increased cardiovascular diseases [27, 28]. In our cohort, febuxostat did not adversely affect the LV systolic and diastolic function in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Thus, in the range of SUA from our cohort, the J-curve association between uric acid and cardiac function was not detected, and lowering medication of hypouricemia should be used in hypouricemia for the cardiac function.

Clinical implication

In this study, e′ decreased and E/e′ increased after 24 months in the control group, suggesting LV compliance has been impaired. In contrast, these parameters showed no significant changes in the febuxostat group. Thus, it is suggested that febuxostat at least did not adversely affect the LV compliance; possibly it acted rather protective for the impairment of LV compliance. We were unable to show the strong evidence of febuxostat to the LV diastolic parameters in the present study, it may be accomplished by long-term observation or using advanced HF cohort.

Limitation

This study was a subanalysis of the PRIZE study and echocardiography was not performed in all subjects. Moreover, the echocardiographic parameters including tricuspid regurgitant jet, pulmonary vein flows, and global longitudinal strains were not performed to assess the diastolic function in detail. Therefore, the number of study subjects was relatively small and included only Japanese patients. Due to the small number of patients, it was statistically difficult to evaluate the relationship between doses and echocardiographic parameters. Further studies enrolling a large number of subjects are needed to confirm the long-term effect of febuxostat on LV diastolic function in patients with hyperuricemia and advanced HF.

Conclusion

Febuxostat might have a potential of preventable effects on the impaired diastolic dysfunction assessed by echocardiography.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants and staff for their contributions to the PRIZE study. The PRIZE study was supported by Teijin Pharma Limited, Japan. The funding body had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

The PRIZE Study Investigators

Principal Investigator Koichi Node11

PRIZE Steering Committee

Toyoaki Murohara12, Teruo Inoue13, Masataka Sata14, Mitsuru Ohishi15

PRIZE Executive Committee

Kotaro Yokote16, Kazuomi Kario17, Hirotaka Watada18, Iichiro Shimomura19, Munehide Matsuhisa14, Yoshihiro Fukumoto20, Koji Maemura21, Yusuke Ohya22

PRIZE Site Investigators

Yuichi Akasaki15, Junya Ako23, Hirohisa Amano13, Kazutaka Aonuma24, Yutaka Aoyama25, Hirofumi Arai26, Kuniya Asai27, Machiko Asaka11, Yoshifumi Awaji28, Noriko Ban29, Toshiaki Ban30, Yasuko K Bando12, Hiroyuki Daida17, Shunsuke Eguchi31, Mami Enomoto24, Yuichi Fujii32, Akinori Fujikake33, Masanori Fujimoto34, Tomohiro Fujisaka35, Shuichi Fujita35, Satoki Fukae21, Daiju Fukuda36, Mieko Fukui37, Yuhei Goriki38, Shuichi Hamasaki39, Tomoya Hara36, Hiroshi Hasegawa16, Kenichi Hashimoto40, Mitsumasa Hata41, Shiro Hata42, Ryo Hayashida12, Akihiro Higashi33, Seiichiro Higuchi34, Akihiro Honda20, Satoshi Hoshide17, Masaaki Hoshiga35, Junko Hotchi36, Sachiyo Igata20, Yumi Ikehara43, Teruo Inoue13, Youhei Inoue38, Hiroko Ishigami25, Masaharu Ishihara44, Hideki Ishii12, Tetsuya Ishikawa33, Takashi Ishimatsu21, Yusuke Ishiyama17, Takahide Ito35, Ayumi Ito25, Toshiaki Kadokami45, Haruo Kamiya46, Soichiro Kashihara45, Yoshihiro Kawamura47, Kazuo Kitagawa48, Yoshio Kobayashi16, Satoshi Kodera49, Seiji Koga50, Hisashi Koide16, Yuji Koide21, Hiroshi Koiwaya38, Hiroki Kojima12, Eri Komai34, Takaaki Komatsu33, Shingo Kono51, Takashi Kono34, Yoshiaki Kubota27, Akio Kuroda52, Takanori Kuroyanagi33, Akifumi Kushiyama53, Kenya Kusunose36, Tatsuya Maruhashi54, Kazuo Matsunaga55, Tomomi Matsuura36, Takafumi Mayama34, Daigo Mine56, Masatoshi Miyamura35, Ryota Morimoto12, Hideaki Morita35, Hidekazu Nagano16, Hidemitsu Nakagawa57, Katsunori Nakamura58, Ryo Nakamura45, Ikuko Nakamura56, Hitoshi Nakashima59, Mamoru Nanasato31, Isao Nishi60, Shinichi Niwano23, Shuichi Nomura32, Nozomu Oda54, Shio Oguchi47, Mitsutoshi Oguri47, Arihide Okahara56, Masaaki Okutsu57, Fumitake Ozaki33, Michishige Ozeki35, Tomoko Saisu61, Yuichi Saito62, Makoto Saitoh63, Yosuke Saka47, Yoshihiko Sakai33, Kazushi Sakane35, Ikki Sakuma34, Shakya Sandeep49, Hiroaki Sano28, Hisakuni Sekino41, Yuka Senoo25, Kensaku Shibata35, Yoshisato Shibata38, Takahisa Shibata30, Akina Shiga34, Kazuki Shiina61, Michio Shimabukuro36, Yusaku Shimbo12, Wataru Shimizu27, Masahisa Shimpo17, Takeshi Soeki36, Koichi Sohmiya35, Hiroyuki Suzuki25, Susumu Suzuki12, Makoto Suzuki64, Nobuhiro Tahara20, Tazu Tahara53, Sadako Takahashi17, Bonpei Takase40, Kaoru Takegami56, Tomoko Takiguchi37, Tomonobu Takikawa47, Ai Tamura34, Tomoaki Tanaka16, Akihito Tanaka12, Hiroyuki Tanaka65, Jun Tanigawa35, Daisuke Tanimura28, Yosuke Tatami12, Takashi Terano29, Fumio Terasaki35, Tomoyuki Tobushi45, Seiko Tokoi13, Toshiyuki Tsubouchi57, Daigaku Uchida66, Tomohiro Ueda32, Rie Ueno36, Hiromi Ueno17, Chikara Ueyama67, Tetsuzo Wakatsuki36, Tomohiko Watanabe35, Masato Watarai68, Isao Yaguchi33, Ayumu Yajima11, Jiko Yamada61, Kyohei Yamamoto29, Sachiko Yamauchi58, Yohei Yamauchi35, Naoto Yokota69, Tomohikov Yoshida29, Goro Yoshioka38

Members of the Data and Safety Monitoring Board

Hiroyuki Daida17, Junya Ako23, Kazuo Kitagawa48

Members of the Clinical Events Committee

Wataru Shimizu27, Yoshio Kobayashi16, Masaharu Ishihara44

Imaging Core Laboratory

Tomoko Ishizu70

Monitoring

Shinichiro Ueda71,72

Trial Secretvariat

Atsushi Tanaka11, Jun-ichi Oyama11, Mikiko Kagiyama11,73,74

Author contributions

All authors conceptualized this trial. K.K. wrote the draft of the article. H.Y. performed statistical analysis throughout this study. All authors confirmed data collection and study selection criteria. All authors enrolled patients and performed study quality assessment. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request (contact via prizesub-secre@clin-med.org).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

A.T. has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim and research funding from GlaxoSmithKline. H.T. received honoraria from Abbott Medical Japan, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Kowa, Ono, Mitsubishi Tanabe and Takeda. Y.F. received research grant from Sanofi KK and Shionogi & Co. Ltd., honoraria from Public Health Research Foundation, AstraZeneca KK, Eisai Co. Ltd., Kowa Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and research grant and honoraria from MSD KK, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo Co. Ltd., Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co. Ltd., Teijin Pharma Ltd., Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd., Mochida Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Astellas Pharma Inc., Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co. Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp., and Pfizer Japan Inc. K. Kario. has received research grant, honoraria and consulting fees from Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co. M.S. has received honoraria from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda, Astellas, Mochida, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Pfizer, Novartis; research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim; scholarships from Astellas, Takeda, Daiichi Sankyo, MSD, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. K.N. has received research grants from Asahi Kasei, Astellas, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Teijin, and Terumo; scholarships from Astellas, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Daiichi Sankyo Healthcare, Takeda, and Teijin; and personal fees from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo Healthcare, Eli Lilly, Kowa, Mitsubishi Tanabe, MSD, Novartis, Ono, Takeda, and Teijin. All other authors declare no competing interests.

No Patient and Public Involvement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A list of authors and their affiliations appears below the Acknowledgement Section.

Contributor Information

Kenya Kusunose, Email: kusunosek@tokushima-u.ac.jp.

The PRIZE Study Investigators:

Koichi Node, Toyoaki Murohara, Teruo Inoue, Masataka Sata, Mitsuru Ohishi, Kotaro Yokote, Kazuomi Kario, Hirotaka Watada, Iichiro Shimomura, Munehide Matsuhisa, Yoshihiro Fukumoto, Koji Maemura, Yusuke Ohya, Yuichi Akasaki, Junya Ako, Hirohisa Amano, Kazutaka Aonuma, Yutaka Aoyama, Hirofumi Arai, Kuniya Asai, Machiko Asaka, Yoshifumi Awaji, Noriko Ban, Toshiaki Ban, Yasuko K. Bando, Hiroyuki Daida, Shunsuke Eguchi, Mami Enomoto, Yuichi Fujii, Akinori Fujikake, Masanori Fujimoto, Tomohiro Fujisaka, Shuichi Fujita, Satoki Fukae, Daiju Fukuda, Mieko Fukui, Yuhei Goriki, Shuichi Hamasaki, Tomoya Hara, Hiroshi Hasegawa, Kenichi Hashimoto, Mitsumasa Hata, Shiro Hata, Ryo Hayashida, Akihiro Higashi, Seiichiro Higuchi, Akihiro Honda, Satoshi Hoshide, Masaaki Hoshiga, Junko Hotchi, Sachiyo Igata, Yumi Ikehara, Youhei Inoue, Hiroko Ishigami, Masaharu Ishihara, Hideki Ishii, Tetsuya Ishikawa, Takashi Ishimatsu, Yusuke Ishiyama, Takahide Ito, Ayumi Ito, Toshiaki Kadokami, Haruo Kamiya, Soichiro Kashihara, Yoshihiro Kawamura, Kazuo Kitagawa, Yoshio Kobayashi, Satoshi Kodera, Seiji Koga, Hisashi Koide, Yuji Koide, Hiroshi Koiwaya, Hiroki Kojima, Eri Komai, Takaaki Komatsu, Shingo Kono, Takashi Kono, Yoshiaki Kubota, Akio Kuroda, Takanori Kuroyanagi, Akifumi Kushiyama, Kenya Kusunose, Tatsuya Maruhashi, Kazuo Matsunaga, Tomomi Matsuura, Takafumi Mayama, Daigo Mine, Masatoshi Miyamura, Ryota Morimoto, Hideaki Morita, Hidekazu Nagano, Hidemitsu Nakagawa, Katsunori Nakamura, Ryo Nakamura, Ikuko Nakamura, Hitoshi Nakashima, Mamoru Nanasato, Isao Nishi, Shinichi Niwano, Shuichi Nomura, Nozomu Oda, Shio Oguchi, Mitsutoshi Oguri, Arihide Okahara, Masaaki Okutsu, Fumitake Ozaki, Michishige Ozeki, Tomoko Saisu, Yuichi Saito, Makoto Saitoh, Yosuke Saka, Yoshihiko Sakai, Kazushi Sakane, Ikki Sakuma, Shakya Sandeep, Hiroaki Sano, Hisakuni Sekino, Yuka Senoo, Kensaku Shibata, Yoshisato Shibata, Takahisa Shibata, Akina Shiga, Kazuki Shiina, Michio Shimabukuro, Yusaku Shimbo, Wataru Shimizu, Masahisa Shimpo, Takeshi Soeki, Koichi Sohmiya, Hiroyuki Suzuki, Susumu Suzuki, Makoto Suzuki, Nobuhiro Tahara, Tazu Tahara, Sadako Takahashi, Bonpei Takase, Kaoru Takegami, Tomoko Takiguchi, Tomonobu Takikawa, Ai Tamura, Tomoaki Tanaka, Akihito Tanaka, Hiroyuki Tanaka, Jun Tanigawa, Daisuke Tanimura, Yosuke Tatami, Takashi Terano, Fumio Terasaki, Tomoyuki Tobushi, Seiko Tokoi, Toshiyuki Tsubouchi, Daigaku Uchida, Tomohiro Ueda, Rie Ueno, Hiromi Ueno, Chikara Ueyama, Tetsuzo Wakatsuki, Tomohiko Watanabe, Masato Watarai, Isao Yaguchi, Ayumu Yajima, Jiko Yamada, Kyohei Yamamoto, Sachiko Yamauchi, Yohei Yamauchi, Naoto Yokota, Tomohikov Yoshida, Goro Yoshioka, Junya Ako, Kazuo Kitagawa, Wataru Shimizu, Masaharu Ishihara, Tomoko Ishizu, Shinichiro Ueda, Atsushi Tanaka, Jun-ichi Oyama, and Mikiko Kagiyama

References

- 1.Feig DI, Kang DH, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1811–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feig DI, Mazzali M, Kang DH, Nakagawa T, Price K, Kannelis J, et al. Serum uric acid: a risk factor and a target for treatment? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(4 Suppl 2):S69–73. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuwabara M, Niwa K, Hisatome I, Nakagawa T, Roncal-Jimenez CA, Andres-Hernando A, et al. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia without comorbidities predicts cardiometabolic diseases: five-year Japanese cohort study. Hypertension. 2017;69:1036–44. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Numa S, Hirai T, Nakagawa K, Ohara K, Fukuda N, Nozawa T, et al. Hyperuricemia and transesophageal echocardiographic thromboembolic risk in patients with atrial fibrillation at clinically low-intermediate risk. Circ J. 2014;78:1600–5. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-13-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiu T-H, Wu P-Y, Huang J-C, Su H-M, Chen S-C, Chang J-M, et al. Hyperuricemia is associated with left ventricular dysfunction and inappropriate left ventricular mass in chronic kidney disease. Diagnostics. 2020;10:514. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10080514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan K-L, Lin J-C, Lin C-L, Chen M-C, Chang S-T, Chung C-M, et al. Impact of gout on left atrial function: a prospective speckle-tracking echocardiographic study. PLoS one. 2014;9:e108357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakanishi K, Daimon M, Yoshida Y, Ishiwata J, Sawada N, Hirokawa M, et al. Serum uric acid level and subclinical left ventricular dysfunction: a community‐based cohort study. ESC heart failure. 2020;7:1031–8. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishnan E, Hariri A, Dabbous O, Pandya BJ. Hyperuricemia and the echocardiographic measures of myocardial dysfunction. Congestive heart failure. 2012;18:138–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2011.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin J-C, Lin C-L, Chen M-C, Chang P-J, Chang S-T, Chung C-M, et al. Gout, not hyperuricemia alone, impairs left ventricular diastolic function. Arthritis research & therapy. 2015;17:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0842-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker MA, Schumacher HR, Jr, Wortmann RL, MacDonald PA, Eustace D, Palo WA, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:2450–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sezai A, Soma M, Nakata K-I, Hata M, Yoshitake I, Wakui S, et al. Comparison of febuxostat and allopurinol for hyperuricemia in cardiac surgery patients (NU-FLASH Trial). Circulation J. 2013:CJ-13-0082. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Tanaka A, Taguchi I, Teragawa H, Ishizaka N, Kanzaki Y, Tomiyama H, et al. Febuxostat does not delay progression of carotid atherosclerosis in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia: a randomized, controlled trial. PLoS medicine. 2020;17:e1003095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oyama J-I, Tanaka A, Sato Y, Tomiyama H, Sata M, Ishizu T, et al. Rationale and design of a multicenter randomized study for evaluating vascular function under uric acid control using the xanthine oxidase inhibitor, febuxostat: the PRIZE study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0409-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–63. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang DH, Park SK, Lee IK, Johnson RJ. Uric acid-induced C-reactive protein expression: implication on cell proliferation and nitric oxide production of human vascular cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3553–62. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirsch GA, Bottomley PA, Gerstenblith G, Weiss RG. Allopurinol acutely increases adenosine triphospate energy delivery in failing human hearts. J Am College Cardiol. 2012;59:802–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamariz L, Harzand A, Palacio A, Verma S, Jones J, Hare J. Uric acid as a predictor of all‐cause mortality in heart failure: a meta‐analysis. Congestive Heart Fail. 2011;17:25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2011.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wełnicki M, Gorczyca I, Wójcik W, Jelonek O, Maciorowska M, Uziębło-Życzkowska B, et al. Hyperuricemia as a marker of reduced left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with atrial fibrillation: results of the POL-AF registry study. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1829. doi: 10.3390/jcm10091829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakagomi A, Saiki Y, Noma S, Kohashi K, Morisawa T, Kosugi M, et al. Effects of febuxostat and allopurinol on the inflammation and cardiac function in chronic heart failure patients with hyperuricemia. IJC Metabolic Endocrine. 2015;8:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcme.2015.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grue JF, Storve S, Støylen A, Torp H, Haugen BO, Mølmen HE, et al. Normal ranges for automatic measurements of tissue Doppler indices of mitral annular motion by echocardiography. Data from the HUNT3 Study. Echocardiography. 2019;36:1646–55. doi: 10.1111/echo.14476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia G, Habibi J, Bostick BP, Ma L, DeMarco VG, Aroor AR, et al. Uric acid promotes left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in mice fed a Western diet. Hypertension. 2015;65:531–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milionis HJ, Kakafika AI, Tsouli SG, Athyros VG, Bairaktari ET, Seferiadis KI, et al. Effects of statin treatment on uric acid homeostasis in patients with primary hyperlipidemia. Am Heart J. 2004;148:635–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu J, Fan YQ, Zhang HL, Zhang JF, Wang CQ. Serum uric acid is associated with incidence of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and cardiovascular events in patients with arterial hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20:560–7. doi: 10.1111/jch.13210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Reboldi G, Santeusanio F, Porcellati C, Brunetti P. Relation between serum uric acid and risk of cardiovascular disease in essential hypertension: the PIUMA study. Hypertension. 2000;36:1072–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.36.6.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss K, Schär M, Panjrath GS, Zhang Y, Sharma K, Bottomley PA, et al. Fatigability, exercise intolerance, and abnormal skeletal muscle energetics in heart failure. Circulation: Heart Fail. 2017;10:e004129. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mátyás C, Németh BT, Oláh A, Török M, Ruppert M, Kellermayer D, et al. Prevention of the development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction by the phosphodiesterase‐5A inhibitor vardenafil in rats with type 2 diabetes. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:326–36. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otaki Y, Watanabe T, Konta T, Watanabe M, Asahi K, Yamagata K, et al. Impact of hyperuricemia on mortality related to aortic diseases: a 3.8-year nationwide community-based cohort study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71301-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawasoe S, Kubozono T, Ojima S, Kawabata T, Miyahara H, Tokushige K, et al. J-shaped curve for the association between serum uric acid levels and the prevalence of blood pressure abnormalities. Hypertens Res. 2021;44:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request (contact via prizesub-secre@clin-med.org).