Abstract

Background

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) as a complementary approach in patients with bulimia nervosa (BN) or binge eating disorder (BED), and to assess how the reduction of the cognitive load of words related to eating disorders (ED) could constitute an intermediate factor explaining its global efficacy.

Methods

Eighty-eight women and men participated in clinical assessments upon inscription, prior to and following 8-week group MBCT. Mindfulness skills were assessed using the five facet mindfulness questionnaire; eating behaviors were assessed using the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ); comorbid pathologies were assessed using the beck depression index and the state-trait anxiety inventory. The cognitive load of words associated with ED was assessed through a modified version of the Stroop color naming task.

Results

Mindfulness skills improved significantly (p < .05) after group MBCT. The improvement of TFEQ scores was accompanied by reduced levels of depressive mood and trait anxiety. The positive impact of MBCT on TFEQ score was directly related to an improvement of the performance in the Stroop task.

Conclusions

MBCT represents an interesting complementary therapy for patients with either BN or BED, at least when cognitive and behavioral domains are concerned. Such efficacy seems to be mediated by the reduction of the cognitive load associated with ED stimuli, which offers a possible explanation of how MBCT could reduce binge-eating behaviors. Other studies are needed, in independent centers, to focus more directly on core symptoms and long-term outcome.

Keywords: binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, eating disorders, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy

Introduction

Lifetime prevalence estimates of the adult community are reported as 0.8% for bulimia nervosa (BN) and 1.4% for binge eating disorder (BED) [1]. Individuals with BN or BED lack control over their eating during binge episodes, feeling like they cannot stop eating, or cannot control the quantity of ingested food. Binge eating is defined as eating large amounts of food in a discrete period of time, coupled with a sense of loss of control over one’s eating and emotional distress [2].

Recently, cognitive theories have been proposed to explain binge eating in terms of its antecedents, function, triggers, consequences, and maintaining factors. Despite clinically significant short-term improvements following cognitive behavioral therapy for many individuals with BN and BED, approximately 50% of the patients remain symptomatic in the long term after treatment [3]. It is suggested that a complementary therapy could be useful to treat these patients.

Mindfulness-based interventions are gaining increasing support as efficient approaches to encourage nonjudgmental acceptance of experience [4]. Indeed, mindfulness-based treatments (MBT) emphasize skills and techniques that facilitate increased acceptance of internal experiences (i.e., thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations) [5]. MBT strategies could target the cognitions that initiate and maintain disordered eating [6]. Using mindfulness in the treatment of eating disorders (ED) could help cultivate awareness of internal experiences, facilitate self-acceptance, increase cognitive flexibility, compassion and forgiveness, and generally improve one’s ability to cope adaptatively with emotions [7–10]. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) could thus have a positive impact on patients with ED as it tackles some of the core aspects of binge eating. Although just a few studies have investigated the application of mindfulness and acceptance-based approaches to disordered eating, early results are promising [5].

Mindfulness is a way of paying attention that is taught through the practice of meditation or other exercises. It is defined as a state of nonjudgmental attention to immediate experience (such as thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations) and an acceptance of moment-to-moment experience [11–14]. Awareness and acceptance of transitory moment allow one to replace automatic thoughts and reactivity to events with conscious and healthier responses [15]. It encourages patients to view emotions and thoughts as transient events that do not require specific behaviors. Mindfulness practices decrease levels of negative affect [16–19]. Their effect is mediated by changes in metacognitions related to emotions and autobiographical memory [20].

Various forms of mindfulness-based interventions have been tested as treatments for individuals with a range of problematic eating behaviors, including emotional or stress-related eating, overeating, and obesity [21]. These interventions typically consist of eight group sessions with a specific topic for each session. MBCT is an extension of Jon Kabat-Zinn’s mindfulness-based stress reduction program.

Studies evaluating the impact of the 8-week mindfulness protocol for patients suffering from ED, and in particular, BN and/or BED, are almost nonexistent. Only Baer et al. [22] have explored an adaptation of MBCT for BED.

Cognitive load can be defined as the mental effort required for an individual to complete a task [23]. The cognitive load theory relies on the assumption that working memory is limited in capacity [24] and that performance drops when the cognitive load increases [25]. Cognitive load can be assessed with the Stroop task [23], which has been used before within the scope of eating behaviors [26, 27]. In this task, subjects are asked to name the color of words [28]. Processing of specifically salient words (such as those related to core aspects of a disorder) imposes a cognitive load that delays color naming [29]. As a result, when words create an attentional bias, naming their color takes longer than when words are neutral [30]. Because food- and body-related stimuli are more salient to individuals with ED [31], the Stroop task with words related to food, body shape, and weight, is an interesting tool to use in this population.

The present study aims to investigate the effectiveness of MBCT, in addition to usual care, in patients with either BN or BED. We hypothesized that MBCT improves eating behaviors as quoted by the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ). Since mindfulness should improve emotion regulation and decrease the negative affect of unpleasant thoughts, we also hypothesized that MBCT decreases the cognitive load of ED-related words. Furthermore, interested in how mindfulness could translate into a higher regulation of eating behaviors, we hypothesized that the efficacy of MBCT on eating behaviors and cognitions was mediated by the reduction of the cognitive load of stressful cues.

Methods

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of the hospital and the Ethical Group of the University (UFR SPSE). Each patient received a letter from the Head of the Psychiatry Department confirming the researchers involved, the objectives of the study, the clinical protocol, and data anonymity prior to the signature of an informed consent form that systematically confirmed their participation. Subjects received no form of payment for participating in the research.

Participants

Eighty-eight patients attending a day hospital at a university hospital specialized in the treatment of ED were enrolled over a 3¾-year period between October 2014 and June 2018. Mean age on enrolment was 30.8 years (standard deviation [SD] = 8.5, range: 19–68), 88% (n = 44) were female, and 75% (n = 66, 1 male) were diagnosed as suffering from BN. Mean body mass index (BMI) was 23.5 (SD = 5.5, range: 16–40).

Patients were evaluated in a clinical interview with a senior psychiatrist to classify their ED based on The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition criteria [2]. Subjects diagnosed with either BN or BED were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included patients diagnosed with anorexia nervosa (AN), schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, or addiction. Five patients with BN had a BMI below 18.5 (but above 16.5). Nutritional interventions and treatments were allowed throughout the experiment.

Patients were assigned to one of six groups, containing from 9 to 12 participants. Some of them were initially placed on a waiting list (WL) prior to participating in the MBCT protocol, the waiting time for which varied from 2 to 6 months. The WL phase was not systematic in order to ensure adequate and coherent group sizes: 54% (n = 33) of patients undertook the WL phase, during which they received usual care. Seventeen patients failed to complete tests and questionnaires for more than one evaluation timepoint; consequently, the final sample size was 71 patients. It was decided to include male patients from the outset, even though the proportion of the overall sample they could represent was unknown.

MBCT protocol

During the MBCT, in addition to usual care, patients took part in eight 2-h weekly sessions over a 2-month duration. Sessions were conducted by a senior instructor and psychologist with more than 14 years of MBCT practice. The program closely followed the standard program conceived by Segal et al. [32], but the psychoeducation was tailored to suit subjects presenting ED rather than depression. Similarly, different cognitive tools were used and the duration of the meditation practices was reduced from 45 to 30 min. The first phase (sessions 1–4) focused on paying attention to the present moment by learning to observe one’s mental dispersion; the second phase (sessions 5–8) focused on a recent problem from daily life in order to develop a different relationship with the unfavorable event and the associated emotions.

Clinical assessments

Tests and questionnaires were completed by patients at three timepoints: upon inscription on WL (T0), prior to group MBCT (T1), and at the end of the protocol (T2). Patients’ weight and height were measured to determine their BMI (weight/height²).

The evolution of mindfulness skills was measured using the Five-Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), a 39-item self-completed questionnaire measuring the five facets of mindfulness: Observing (8 items), Describing (8 items), Acting with awareness (8 items), Nonjudgmental (8 items), and Nonreactive (7 items). Items are rated on 5-point Likert scales (1 = never or very rarely true to 5 = very often or always true), each facet score ranges from 8 to 40, except for the nonreactive facet which ranges from 7 to 35. For each facet, higher scores indicate higher levels of mindfulness [33].

Eating behaviors were evaluated using the TFEQ, a 51-item self-assessment scale assessing three factors: Cognitive restraint (CR) (21 items), Disinhibition (16 items), and Hunger (14 items). Each item is scored either 0 or 1. Minimum scores for the three factors are 0, maximum scores 21, 16, and 14, respectively. Higher scores indicate higher levels of restrained eating, disinhibited eating, and predisposition to hunger [34]. The TFEQ has psychometric support including predictive validity [35].

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [36] and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [37] were administered to assess comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms respectively. The BDI is a 21-question multiple-choice self-report inventory. Each question has four possible responses, ranging in intensity, scored from 0 to 3. Higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms. The STAI (form Y) is a 40-item self-evaluation questionnaire for assessing trait anxiety (20 items) and state anxiety (20 items). All items are rated on 4-point scales (e.g., from “Almost Never” to “Almost Always”). Higher scores indicate greater anxiety.

Eating disorder Stroop task

Following a search of the international literature, we chose a modified version of the Stroop task published by Cooper and Todd [27], who validated the adaptation of the test to ED. A French translation of this ED-specific Stroop task was developed following consultation with the corresponding author.

Ten cards were generated. Each card was made up of 25 words printed on a white background in 5 rows of 5 words. Each word was printed in one of five colors: red, green, black, blue, or yellow. Each of the five stimulus words was repeated five times. In each block of five words, each of the five words and each of the five colors occurred once.

The 10 cards were organized into 5 pairs and presented in a fully balanced design. In each pair, the target card followed the control card. The pairings were: congruent words and colors versus incongruent words and colors; transport versus food; household objects versus weight; nature versus body shape; and communication versus depression.

Patients were instructed to name the color of the ink in which each word was written as quickly as possible and to correct any errors immediately after their occurrence. The time taken to name the color of all the words on each card was recorded using a digital stopwatch. Subsequently, the total time taken to name all neutral words (six cards: congruent colors, incongruent colors, transport, objects, nature, and communication) and all ED-related words (three cards: food, weight, and shape) were calculated.

The test was administered at timepoints T0, T1, and T2, following the clinical interview with the senior instructor and prior to completion of the clinical assessments.

Statistical analysis

All analyses, except path analyses, were performed with the PASW Statistics18 software. Normal distributions of variables were checked using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test prior to analysis. Score changes were calculated for the WL period (difference between timepoints T1 and T0) and for the duration of MBCT (difference between timepoints T2 and T1). T-tests were performed for statistical comparison between WL and MBCT. Homogeneity of variances was confirmed using the Levene statistic. The significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Multivariate approaches were performed by logistic regression to evaluate the role of any potentially contaminating factors. This analysis used the condition MBCT versus WL as the dependent variable, and the following independent variables: change of TFEQ scores as the expected improvement, and changes of BDI (depression) and STAI-State (anxiety) scores as potential confounders. The hypothesis was that any improvement of the TFEQ score as a parameter was independent of any improvement following MBCT, and not merely a reflection of an improvement of mood or anxiety scores.

Path analyses were conducted using PROCESS statistics for SPSS v3.5, to assess the direct impact of MBCT on the improvement of the TFEQ score and the mediating effect of Stroop performance.

Results

After MBCT, four out of the five facets of the FFMQ showed statistically significant improvements: Observing (t = 2.34, p = 0.01), Describing (t =1.71, p = 0.05), Nonjudging of inner experience (t = 1.63, p = 0.05), and Nonreactivity to inner experience (t = 1.77, p = 0.04). The only facet not to improve significantly was Acting with awareness (t = 1.39, p = 0.08). The effect sizes were small to moderate (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of mindfulness capacities (FFMQ), eating behavior (TFEQ), depressive symptoms (BDI), trait and state anxiety (STAI), and emotional reactivity (modified Stroop test for ED) in 61 patients treated for an ED following inscription on a waiting list (WL) and before and after 8 weeks of group MBCT.

| Parameters | Baseline values at study enrolment | WL | MBCT | Difference from 0 of | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (T0) | (T1–T0) (N = 33) | (T2–T1) (N = 52) | (T2–T1)–(T1–T0) | ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | df | p-value | Cohen’s d | ||

| FFMQ | Observing | 22.2 | 6.58 | −0.58 | 3.40 | 1.71 | 4.88 | 2.34 | 82 | 0.01* | 0.53 |

| Describing | 21.4 | 6.86 | −0.03 | 3.38 | 1.59 | 4.71 | 1.71 | 82 | 0.05* | 0.39 | |

| Awarenessa | 22.1 | 6.49 | −0.76 | 5.68 | 1.04 | 5.86 | 1.39 | 82 | 0.08 | 0.31 | |

| Nonjudgingb | 21.3 | 5.88 | 0.00 | 5.23 | 2.27 | 6.79 | 1.63 | 82 | 0.05 | 0.37 | |

| Nonreactivityc | 12.4 | 3.14 | 0.51 | 2.25 | 1.86 | 4.67 | 1.77 | 82 | 0.04* | 0.35 | |

| TFEQ | Cognitive restraint | 12.1 | 4.66 | −0.19 | 2.28 | −1.30 | 2.76 | 1.90 | 82 | 0.06 | −0.43 |

| Disinhibition | 11.1 | 3.71 | 0.09 | 1.51 | −1.00 | 2.76 | 2.31 | 82 | 0.02* | −0.46 | |

| Hunger | 7.2 | 4.27 | 0.56 | 2.44 | −0.64 | 2.44 | 2.18 | 82 | 0.03* | −0.50 | |

| Total | 30.3 | 7.02 | 0.47 | 4.70 | −2.92 | 6.02 | 2.72 | 82 | 0.01** | −0.61 | |

| BDI | 11.3 | 4.81 | −0.03 | 4.93 | −2.50 | 4.92 | 2.55 | 82 | 0.01** | −0.51 | |

| STAI-State | 63.2 | 10.90 | −0.51 | 11.90 | −3.69 | 12.40 | 1.18 | 82 | 0.18 | −0.26 | |

| STAI-Trait | 64.7 | 9.07 | −0.39 | 7.11 | −4.52 | 9.02 | 2.35 | 82 | 0.01* | −0.49 | |

| Stroop words | Congruent colors | 15.4 | 3.84 | −2.48 | 3.71 | −1.17 | 3.62 | 1.60 | 82 | 0.06 | 0.36 |

| Incongruent colors | 25.2 | 10.20 | −2.58 | 7.54 | −3.66 | 5.08 | 0.72 | 82 | 0.24 | −0.18 | |

| Transport | 18.0 | 5.23 | −1.48 | 2.36 | −0.74 | 1.98 | 1.50 | 82 | 0.07 | 0.35 | |

| Objects | 16.7 | 3.88 | 0.17 | 2.09 | −1.22 | 2.85 | 2.59 | 82 | 0.01** | −0.53 | |

| Nature | 18.1 | 4.19 | −0.80 | 2.37 | −0.93 | 2.61 | 0.24 | 82 | 0.41 | −0.05 | |

| Communication | 16.1 | 5.52 | 0.41 | 2.39 | −0.81 | 2.80 | 2.14 | 82 | 0.02* | −0.46 | |

| All neutral words | 84.3 | 19.00 | −4.18 | 6.91 | −4.87 | 7.41 | 0.44 | 82 | 0.33 | −0.10 | |

| Food | 17.8 | 3.13 | −0.19 | 3.25 | −1.50 | 3.04 | 1.86 | 82 | 0.03* | −0.43 | |

| Weight | 20 | 6.09 | −1.01 | 3.62 | −1.78 | 2.66 | 1.05 | 82 | 0.15 | −0.26 | |

| Shape | 18.5 | 4.48 | −0.87 | 2.25 | −1.83 | 2.40 | 1.87 | 82 | 0.03* | −0.41 | |

| All ED words | 56.2 | 13.00 | −2.06 | 5.83 | −5.11 | 5.84 | 2.35 | 82 | 0.01* | −0.53 | |

| Depression-related words | 18.5 | 4.95 | −0.95 | 2.50 | −0.94 | 3.57 | 0.02 | 82 | 0.49 | <0.01 | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BDI, Beck depression inventory; FFMQ, five facets mindfulness questionnaire; MBCT, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; STAI, state-trait anxiety inventory; TFEQ, three-factor eating questionnaire; WL, waiting list.

Acting with awareness.

Nonjudging of inner experience.

Nonreactivity to inner experience.

p ≤ 0.05.

p ≤ 0.01.

We observed a significant improvement in TFEQ results during MBCT, with a moderate total effect size (Table 1). The level of depressive mood and the trait condition of anxiety also significantly improved after MBCT and not so following inscription on the WL (Table 1). Furthermore, when assessing the efficacy of MBCT on TFEQ score, we observed no impact of the sessions (F = 0.259, p = 0.933), gender (t = 1.196, p = 0.119), diagnoses (F = 0.231, p = 0.633), age (r = 0.01, p = 0.969), or baseline BMI (r = −0.075, p = 0.603).

The logistic regression analysis showed that only TFEQ improvement was significant (Wald χ² = 4.65, df = 1, p = 0.03) following MBCT, while BDI (Wald χ² = 2.93, df = 1, p = 0.09) and state anxiety (Wald χ² = 0.253, df = 1, p = 0.62) were not.

In the Stroop task, reaction times for ED-related words were shortened (t = 2.24, p = 0.01, d = 0.52) by MBCT, whereas those for neutral (t = 0.349, p = 0.36, d = 0.08) and mood (t = 0.015, p = 0.49, d < 0.01) words were not (Table 1).

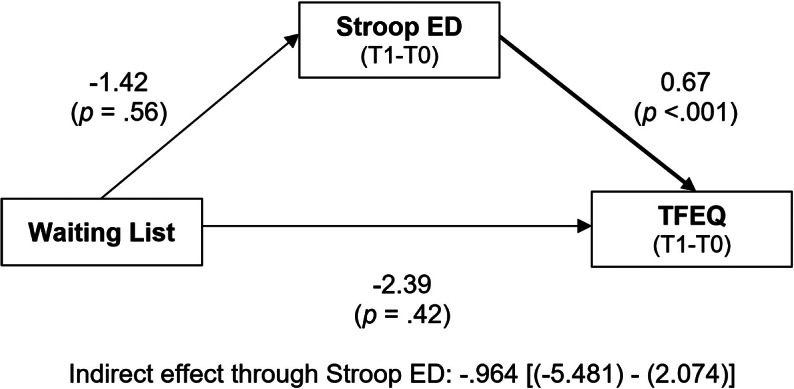

The path analysis on the effect of being tested twice, before and after the WL (control intervention, Figure 1), showed no direct effect neither on TFEQ score (t = −0.804, p = 0.42) nor on reaction times in the Stroop task for ED-related words (t = −0.600, p = 0.56). TFEQ score was significantly predicted by reaction times (t = 5.545, p < 0.001). The bootstrapping indirect effect of WL on TFEQ score improvement through Stroop performance was not significant (CI 95% [(−5.481) − (+2.074)]).

Figure 1.

Path analysis of the impact of the “waiting list” on “TFEQ” score, directly, and through its impact on the “Stroop ED” test (for words related to eating disorders).

Changes for both TFEQ score and performance in the emotional Stroop task associated with the waiting list correspond to the difference between timepoints T0 and T1. Bold arrows indicate significant paths (p<.05). There was no direct effect of the waiting list neither on the TFEQ score nor on emotional Stroop performance for ED-related words. ED symptoms improvement was significantly predicted by emotional Stroop performance.

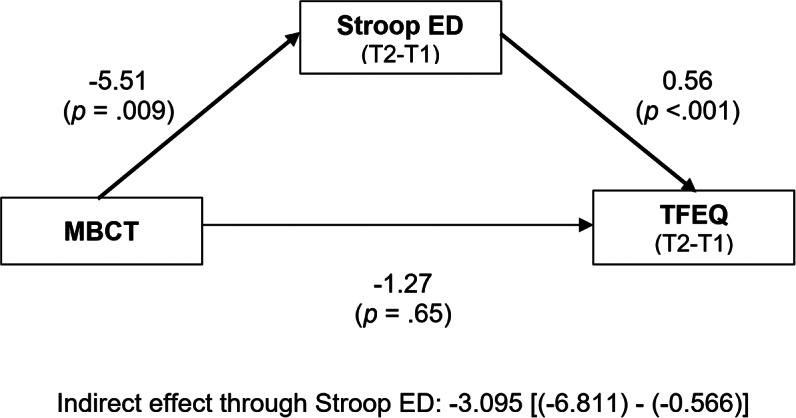

A similar path analysis performed before and after MBCT (studied intervention, Figure 2) showed no residual direct effect of MBCT on TFEQ score (t = −0.449, p = 0.65), but a strong effect on reaction times in the Stroop task for ED-related words (t = 4.231, p = 0.009). TFEQ score improvement was significantly mediated by the improvement of reaction times (F = 10.227, p < 0.001). The bootstrapping indirect effect of MBCT on TFEQ score improvement through Stroop performance was significant (CI 95% [(−6.811) − (−0.566)]).

Figure 2.

Path analysis of the impact of the mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (“MBCT”) on “TFEQ” score, directly, and through its impact on the “Stroop ED” test (for words related to eating disorders).

Changes for both TFEQ score and performance in the emotional Stroop task associated with MBCT correspond to the difference between timepoints T1 and T2. Bold arrows indicate significant paths (p<.05). There was no direct effect of MBCT on the TFEQ score but a strong effect on emotional Stroop performance for ED-related words. ED symptoms improvement was significantly predicted by emotional Stroop performance.

None of the preceding results were changed when the five patients with a BMI below 18.5 were excluded (data not shown).

Discussion

The impact of MBCT was assessed on patients with either BN or BED. We found that MBCT significantly improved mindfulness, TFEQ scores and reaction times in the Stroop task. It also had a significant positive impact on depression and trait anxiety. The improvement of the three factors of ED tested by the TFEQ (dietary restriction, disinhibition, and hunger) was mediated by the reduction of reaction times in the Stroop task for words related to food, weight, and shape. These results support the idea that MBCT could induce positive changes in disordered eating, such as improving eating behaviors and, in parallel and independently, the anxiety and depressive symptoms tested herein.

Our study confirms the few results published in literature regarding the impact of MBCT for patients with BN or BED. Previous reviews have suggested that mindfulness-based interventions are effective in reducing symptoms of ED [7, 38, 39] and could reduce binge episodes and dichotomous thinking, body image concern, and emotional eating [7, 21]. Similarly, our results concerning improvement in mindfulness, anxiety, and external-based eating are consistent with those of Daubenmier et al. [40]. However, the sample tested herein is larger than the subject populations comprised in most of these studies.

In the original version of the Stroop task [28], subjects are asked to name the color of color names written in congruent or incongruent colors. This version of the task measures the ability to refrain from reading the color name and to name the color of the ink. In the modified version that we used [27], the difficulty does not arise from congruent or incongruent colors, but depends on the salience of the words [30]. Indeed, words related to eating disorder have an increased cognitive load, which interferes with the ability to complete the task [29]. Cooper and Todd, whose version of the Stroop test we used, reported that patients with ED took longer to color name words related to their concerns with eating, weight, and body shape than neutral words [27]. In the present study, we found that patients were faster to color name ED-related words post-MBCT than pre-MBCT. This suggests that MBCT efficiently decreased their concerns/biases with food, weight, and body shape and, by doing so, reduced the salience and the resulting cognitive load of ED-related words.

Impulsivity promotes binge-eating behaviors in both BN [41] and BED [42]. Mindfulness and impulsivity are generally negatively correlated; indeed, Urgency (one of the facets of impulsivity) was reported to be negatively and strongly associated with Acting with Awareness, Nonreactivity, and Nonjudgment [43]. MBCT could therefore reduce binge-eating behaviors by improving mindfulness and consequently decrease impulsiveness. An alternative explanation could rather propose that MBCT targets executive control and/or emotion regulation. In a study devoted to bereavement and depression, MBCT facilitated the executive control function by alleviating the emotional interferences over the cognitive functions, suggesting that the MBCT intervention significantly improved both executive control and emotion regulation [44]. In the present study, however, the co-occurring improvement of mood was not involved in the improvement of eating behaviors, while we observed a significant role of the reduction of the cognitive load of ED-related words. This suggests that cognitions (inhibitory control) rather than emotions are the leverage of MBCT efficacy in ED.

As mindfulness-based interventions primarily aim to facilitate self-acceptance, improve the ability to cope with emotions and decrease levels of negative affect [7–10, 16–19], it is not surprising that MBCT was associated with a reduction of anxiety and depressive symptoms. This constitutes another significant advantage of using MBCT as a complementary therapy in patients with ED who often suffer from depression and anxiety [45, 46].

Our findings are in accordance with the strength model of self-regulation [47–49]. This model posits that individuals have a limited capacity to regulate certain states (e.g., affect and hunger), and can benefit from mindfulness interventions to continue to increase their capacity for self-regulation, affective stability and flexibility, coping skills, and reduced reactivity toward stress-induced bulimic compulsions.

Four limitations should be considered in the present study.

First, the fact that just 54% of patients completed the WL phase prior to MBCT reduced the statistical power to detect an effect in this specific group and in the global sample. The inclusion of patients in the WL was stopped at least 4 weeks before the first MBCT group started, in order to ensure a sufficiently long waiting time, which is at least 1 month. This strategy was decided to reduce the negative consequences of the protocol in the treatment proposed in our center, and reduce the risk of biases associated with the inclusion of just volunteers. Our WL multiple baseline therefore cannot be considered as random, but probably facilitated the low attrition rate (22%) that we obtained.

Second, WL conditions may act as a nocebo in psychotherapy trials [50], and this might be amplified by our multiple baselines. The suspicion that this might lead to different effect size estimates did not form part of this study. Future research should address this weakness, notably by preplanning sensitivity analyses and performing post hoc analyses on findings of significant differences in order to adjust for potential publication bias.

Third, our tests lacked an evaluation of general psychopathology. Regarding the neuropsychological assessment, we only included in our study the Stroop test, but additional measures regarding memory and executive functions would have been useful. The Stroop task has some well-known limitations, such as variable scoring methods [51], a contaminating role of optometric [52], presence of dyslexia [53] or depressive disorder [54], honesty of responses [55] or even gum-chewing [56]. Furthermore, the Stroop task probably tested variable dimensions of cognitive control [57]. Knowing that pupil size increases as task demand rises, the observation of a steep increase of pupil size when reading incongruent distractors is reassuring [58]. Likewise, finding in our sample that mood and anxiety improved independently from reaction times is also reassuring. Associating different neurocognitive tests with the Stroop task would help define the neurocognitive aspects which could explain the positive effect of MBCT in ED.

Fourth, path analyses attribute the impact of an intervention on one intermediate factor to explain a global effect on another. While detecting that Stroop performance mediates the improvement of the TFEQ score is interesting, these analyses do not take into account that such effect probably differs from one patient to another. In other words, MBCT probably has more obvious efficacy in specific patient subgroups, and our sample was too small to be able to define them. In the same line, the instruments used in the present protocol only reflect some aspects of eating, mood and anxiety disorders, and cannot be considered representative of the large heterogeneity of patients having these disorders.

In conclusion, while the current study presents interesting findings on the role of group MBCT and its relationship with eating behaviors, future research will be important to include biological parameters and other tests of cognitive flexibility and functioning.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by an unrestrictive grant from Fondation de l’Avenir (AP-RM-16-040). The authors thank Daphnée Poupon for her help for editing and finalizing the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not available.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: P.D.; Formal analysis: P.G.; Methodology: P.G.; Data curation: C.V.; Writing –review & editing: P.G.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- [1].Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Chiu WT, Deitz AC, Hudson JI, Shahly V, et al. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:904–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Burton AL, Abbott MJ. Conceptualising binge eating: a review of the theoretical and empirical literature. Behaviour Change. 2017;34:168–98. doi: 10.1017/bec.2017.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol. 2003;10:125–43. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Barney JL, Murray HB, Manasse SM, Dochat C, Juarascio AS. Mechanisms and moderators in mindfulness- and acceptance-based treatments for binge eating spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2019;27:352–80. doi: 10.1002/erv.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Baer RA, Fischer S, Huss DB. Mindfulness and acceptance in the treatment of disordered eating. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther. 2005;23:281–300. doi: 10.1007/s10942-005-0015-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Baer RA, Fischer S, Huss DB. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy applied to binge eating: a case study. Cogn Behav Pract. 2005;12:351–8. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(05)80057-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kristeller JL, Baer RA, Quillian-Wolever R. Mindfulness-based approaches to eating disorders. In: RA Baer editor Mindfulness-based treatment approaches: clinician’s guide to evidence base and applications, San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006, p. 75–91. doi: 10.1016/B978-012088519-0/50005-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kristeller JL, Wolever RQ. Mindfulness-based eating awareness training for treating binge eating disorder: the conceptual foundation. Eat Disord. 2011;19:49–61. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2011.533605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wolever RQ, Best JL. Mindfulness-based approaches to eating disorders. In: Didonna F, editor. Clinical handbook of mindfulness, New York, NY: Springer; 2009, p. 259–87. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09593-6_15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kabat-Zinn J, Hanh TN. Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, USA: Random House Publishing Group; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1982;4:33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever you go, there you are: mindfulness meditation in everyday life. California, USA: Hachette Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, et al. Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clin Psychol. 2004;11:230–41. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sears S, Kraus S. I think therefore I om: cognitive distortions and coping style as mediators for the effects of mindfulness meditation on anxiety, positive and negative affect, and hope. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65:561–73. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Arch JJ, Craske MG. Mechanisms of mindfulness: emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1849–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ortner CNM, Kilner SJ, Zelazo PD. Mindfulness meditation and reduced emotional interference on a cognitive task. Motiv Emot. 2007;31:271–83. doi: 10.1007/s11031-007-9076-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tang Y-Y, Ma Y, Wang J, Fan Y, Feng S, Lu Q, et al. Short-term meditation training improves attention and self-regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17152–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707678104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Vinci C, Peltier MR, Shah S, Kinsaul J, Waldo K, McVay MA, et al. Effects of a brief mindfulness intervention on negative affect and urge to drink among college student drinkers. Behav Res Ther. 2014;59:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Teasdale JD, Moore RG, Hayhurst H, Pope M, Williams S, Segal ZV. Metacognitive awareness and prevention of relapse in depression: empirical evidence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:275–87. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Alberts HJEM, Thewissen R, Raes L. Dealing with problematic eating behaviour. The effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on eating behaviour, food cravings, dichotomous thinking and body image concern. Appetite. 2012;58:847–51. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Baer RA. Mindfulness-based treatment approaches: clinician’s guide to evidence base and applications. Burlington, MA, USA: Elsevier; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gwizdka J. Using stroop task to assess cognitive load. In: Neerincx M, Brinkman editor Proceedings of the 28th Annual European Conference on Cognitive Ergonomics, New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery; 2010, p. 219–22. doi: 10.1145/1962300.1962345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Paas F, van Gog T, Sweller J. Cognitive load theory: new conceptualizations, specifications, and integrated research perspectives. Educ Psychol Rev. 2010;22:115–21. doi: 10.1007/s10648-010-9133-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Klepsch M, Schmitz F, Seufert T. Development and validation of two instruments measuring intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1997. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lattimore P, Maxwell L. Cognitive load, stress, and disinhibited eating. Eat Behav. 2004;5:315–24. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cooper M, Todd G. Selective processing of three types of stimuli in eating disorders. Br J Clin Psychol. 1997;36:279–81. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol. 1935;18:643–62. doi: 10.1037/h0054651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bielecki M, Popiel A, Zawadzki B, Sedek G. Age as moderator of emotional stroop task performance in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Front Psychol. 2017;8:1614. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ben-Haim MS, Williams P, Howard Z, Mama Y, Eidels A, Algom D. The emotional Stroop task: assessing cognitive performance under exposure to emotional content. J Vis Exp. 2016;112: 53720. doi: 10.3791/53720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhu Y, Hu X, Wang J, Chen J, Guo Q, Li C, et al. Processing of food, body and emotional stimuli in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2012;20:439–50. doi: 10.1002/erv.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach to preventing relapse. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, Button D, Krietemeyer J, Sauer S, et al. Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment 2008;15:329–42. doi: 10.1177/1073191107313003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Blomquist KK, Grilo CM. Predictive significance of changes in dietary restraint in obese patients with binge eating disorder during treatment. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44:515–23. doi: 10.1002/eat.20849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, 1970.

- [38].Wanden-Berghe RG, Sanz-Valero J, Wanden-Berghe C. The application of mindfulness to eating disorders treatment: a systematic review. Eat Disord. 2011;19:34–48. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2011.533604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Courbasson CM, Nishikawa Y, Shapira LB. Mindfulness-action based cognitive behavioral therapy for concurrent binge eating disorder and substance use disorders. Eat Disord. 2011;19:17–33. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2011.533603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Daubenmier J, Kristeller J, Hecht FM, Maninger N, Kuwata M, Jhaveri K, et al. Mindfulness intervention for stress eating to reduce cortisol and abdominal fat among overweight and obese women: an exploratory randomized controlled study. J Obes. 2011;2011:651936. doi: 10.1155/2011/651936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Howard M, Gregertsen EC, Hindocha C, Serpell L. Impulsivity and compulsivity in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113354. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Boswell RG, Grilo CM. General impulsivity in binge-eating disorder. CNS Spectr. 2021;26:538–44. doi: 10.1017/S1092852920001674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Murphy C, Mackillop J. Living in the here and now: interrelationships between impulsivity, mindfulness, and alcohol misuse. Psychopharmacology. 2012;219:527–36. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2573-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Huang F-Y, Hsu A-L, Hsu L-M, Tsai J-S, Huang C-M, Chao Y-P, et al. Mindfulness improves emotion regulation and executive control on bereaved individuals: an fMRI study. Front Hum Neurosci. 2018;12:541. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Casper RC. Depression and eating disorders. Depress Anxiety. 1998;8 Suppl 1:96–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Godart NT, Flament MF, Lecrubier Y, Jeammet P. Anxiety disorders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: co-morbidity and chronology of appearance. Eur Psychiatry. 2000;15:38–45. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Tice DM. The strength model of self-control. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16:351–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hagger MS, Wood C, Stiff C, Chatzisarantis NLD. The strength model of self-regulation failure and health-related behaviour. Health Psychol Rev. 2009;3:208–38. doi: 10.1080/17437190903414387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Muraven M, Baumeister RF. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychol Bull. 2000;126:247–59. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Furukawa TA, Noma H, Caldwell DM, Honyashiki M, Shinohara K, Imai H, et al. Waiting list may be a nocebo condition in psychotherapy trials: a contribution from network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130:181–92. doi: 10.1111/acps.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Scarpina F, Tagini S. The Stroop color and word test. Front Psychol. 2017;8:557. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Daniel F, Kapoula Z. Binocular vision and the Stroop test. Optom Vis Sci. 2016;93:194–208. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Proulx MJ, Elmasry H-M. Stroop interference in adults with dyslexia. Neurocase. 2015;21:413–7. doi: 10.1080/13554794.2014.914544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kertzman S, Reznik I, Hornik-Lurie T, Weizman A, Kotler M, Amital D. Stroop performance in major depression: selective attention impairment or psychomotor slowness? J Affect Disord. 2010;122:167–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Boskovic I, Biermans AJ, Merten T, Jelicic M, Hope L, Merckelbach H. The modified Stroop task is susceptible to feigning: Stroop performance and symptom over-endorsement in feigned test anxiety. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1195. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kawakami Y, Takeda T, Konno M, Suzuki Y, Kawano Y, Ozawa T, et al. Relationships between gum chewing and stroop test: a pilot study. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;977:221–6. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-55231-6_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Purmann S, Pollmann S. Adaptation to recent conflict in the classical color-word Stroop-task mainly involves facilitation of processing of task-relevant information. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:88. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Laeng B, Ørbo M, Holmlund T, Miozzo M. Pupillary Stroop effects. Cogn Process. 2011;12:13–21. doi: 10.1007/s10339-010-0370-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not available.