Abstract

The establishment of continental-scale drainage systems on Earth is largely controlled by topography related to plate boundary deformation and buoyant mantle. Drainage patterns of the great rivers in Asia are thought to be highly dynamic during the Cenozoic collision of India and Eurasia, but the drainage pattern and landscape evolution prior to the development of high topography in eastern Tibet remain largely unknown. Here we report the results of petro-stratigraphy, heavy-mineral analysis, and detrital zircon U-Pb dating from late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene sedimentary basin strata along the present-day eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau. Similarities in the provenance signatures among basins indicate that a continental-scale fluvial system once drained southward into the Neo-Tethyan Ocean. These results challenge existing models of drainage networks that flowed toward the East Asian marginal seas and require revisions to inference of palaeo-topography during the Late Cretaceous. The presence of a continent-scale river may have provided a stable long-term base level which, in turn, facilitated the development of an extensive low-relief landscape that is preserved atop interfluves above the deeply incised canyons of eastern Tibet.

Subject terms: Geomorphology, Stratigraphy, Tectonics, Sedimentology

This study provides evidence for a continental-scale river system that existed in eastern Tibet before the India-Asia collision. The river system developed an extensive low-relief landscape, which was uplifted and dissected during the late Cenozoic.

Introduction

Many continental-scale river systems on Earth have evolved over prolonged geological histories1–5 and their regimes were often established in tectonically stable settings1,4. Hence, the development of such drainage systems has been argued to reflect long-term maintenance of low-amplitude but long-wavelength topographic gradients4,6. The persistence of a stable base level thus provides a governing factor that enables reduction of topographic relief and promotes the development of continental-scale landscapes with subdued topography2,4,7.

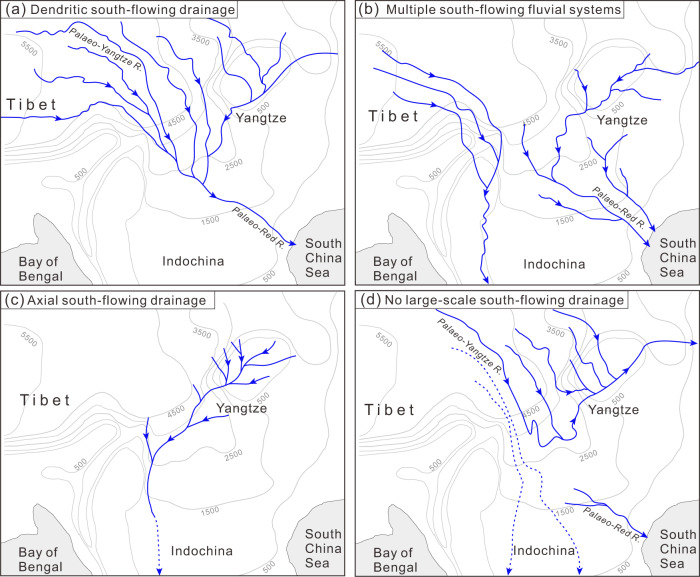

The high topography associated with the India-Eurasia collision zone hosts several great rivers (Fig. 1a), and the history of their drainage networks is central to debates about the uplift and landscape evolution of the Tibetan Plateau8–12. The Yangtze River – the largest river in Asia – emanates from eastern Tibet before being successively joined by other major rivers and flowing into the East China Sea (Fig. 1a). The evolution of the Yangtze River system and its large tributaries, which drain the amalgamated terranes of continental China (e.g., Songpan-Ganzi, Yidun and Yangtze terranes), is intimately linked to Cenozoic uplift of the eastern Tibetan Plateau and is therefore of great interest for all studies attempting to understand the tectonic and landscape evolution of the plateau3,8,9,13. Geomorphic observations suggest that the modern rivers draining eastern Tibet were once tributaries to a big, southward-flowing river that had a Mississippi-like drainage pattern6 (Fig. 2a). Many studies have addressed the origin and development of this river system from different perspectives, and it has been suggested that a palaeo-Red River once connected Tibet with the South China Sea13–15. However, both the pattern and the age of this river system remain highly controversial (Fig. 2), with age estimates ranging from Cretaceous to Quaternary11,13–16. Moreover, the poor preservation of fluvial landscapes and a lack of studies focusing on regional sedimentary linkages have led some researchers to question the existence of a south-flowing river17,18 (Fig. 2d).

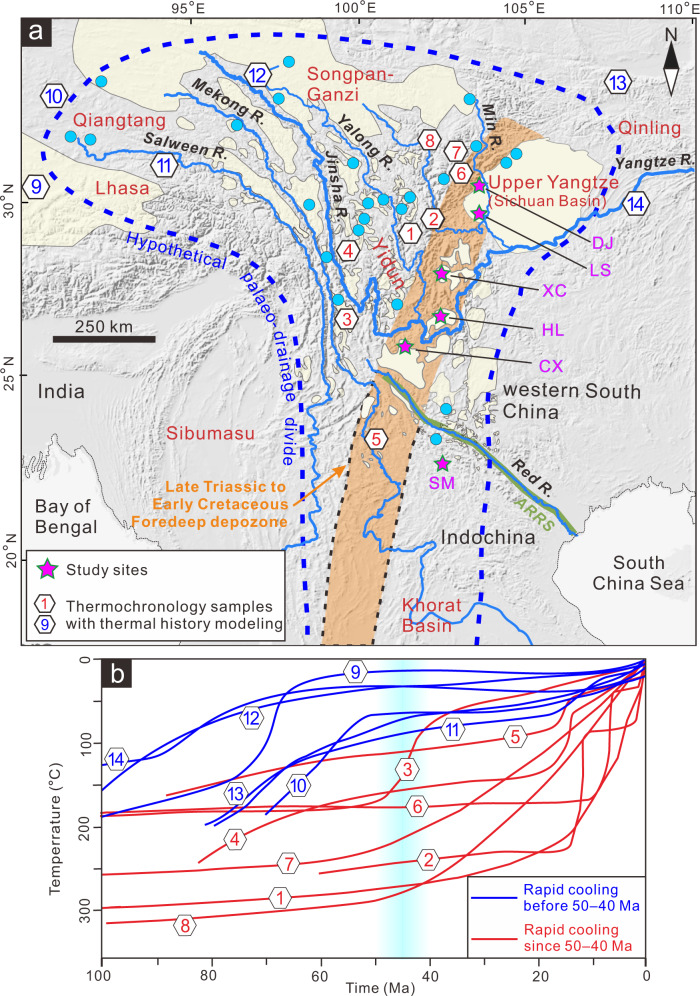

Fig. 1. Location map of study area and thermal modelling results of thermochronological data in eastern Tibet and surrounding areas.

a Map showing main tectonic units (red text) and major river systems. Light yellow polygons indicate mapped low-relief surfaces (modified after refs. 20,61). Blue circles correspond to AFT and AHe thermochronological ages of ~50–100 Ma from low-relief plateau areas24,31–34,36,67. Hexagons indicate sites with late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene cooling histories (shown in Fig. 1b). Dashed blue line represents the hypothetical drainage divide of late Cretaceous to early Palaeogene drainage system. Orange area marks the inferred location of a late Triassic to early Cretaceous foredeep depozone (cf. refs. 20,27). Abbreviations for sites: ARRS Ailaoshan–Red River shear zone, DJ Dujiangyan area, LS Leshan area, XC Xichang Basin, HL Huili Basin, CX Chuxiong Basin, SM Simao Basin. b Red lines indicate slow cooling rates (~1 °C/Ma) during late Cretaceous to early Palaeogene, whereas blue lines show more rapid cooling rates (~5–10 °C/Ma) during the same period. Light blue vertical band indicates age range (~50–40 Ma) of the onset of rapid cooling in eastern Tibet. 1–ref.24; 2–ref. 12; 3–ref. 36; 4–ref. 65; 5–ref. 66; 6–ref. 35; 7,8–ref. 28; 9–ref. 31; 10–ref. 37; 11,12–ref. 32; 13–ref.34; 14–ref. 38. See Fig. 1a for localities. (The shaded-relief map is generated by Xudong Zhao using DEM data (https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/topo/) and ArcGIS software).

Fig. 2. Postulated drainage scenarios in SE Tibet before establishment of the modern river network.

a Continental-scale, dendritic south-flowing river system which drained into the South China Sea6,15. b A south-flowing river system linking the Upper Yangtze terrane to the South China Sea13. c A south-flowing transcontinental drainage that developed on the western South China Block16. d An east-flowing river system similar to the modern drainage network, with no connection between the palaeo-Yangtze River and the palaeo-Red River17,18 (or other south-flowing rivers).

The presence of a high-elevation, low-relief landscape in eastern Tibet has often been linked to drainage evolution6,19. Some interpreted these low-relief surfaces as a result of river incision into a pre-existing erosion surface10,20–22; others argued that the low-relief landscape formed at high elevation due to reduced erosional efficiency following drainage capture19, highland denudation and basin filling within internal drainages23, or smoothing of the highlands by efficient glacial erosion24. However, these previous interpretations were recently argued to be insufficient because the respective processes were only documented locally, and drainage capture and divide migration cannot form the observed low-relief landscape in eastern Tibet21. Thus, the question of how the low-relief landscape preserved in eastern Tibet has formed remains largely unresolved.

Late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene (K2–E1) terrestrial sediments are preserved in several basins in eastern Tibet16,25,26 (Fig. 1a), enabling us to reconstruct the evolution of the drainage network prior to the establishment of high topography in the Late Cenozoic. Here, we characterise the provenance and dispersal pattern of the related drainage system prior to the India–Eurasia collision and show, for the first time, that much of the region now elevated as Tibetan Plateau, was drained by a low-gradient, continental-scale river that flowed into the Neo-Tethyan Ocean. We suggest that the relatively stable base level and long-term tectonic stability required for the maintenance of this river played a central role in the development of a low-relief region in the continental interior during Late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene time.

Results

Prolonged late Mesozoic tectonic stability in eastern Tibet

The geologic provinces that comprise eastern Tibet represent distinct tectonostratigraphic terranes that were successively amalgamated during the closure of the Palaeo- and Meso-Tethyan oceans in the Triassic27. The Songpan-Ganzi and Yidun terranes, which now form much of eastern Tibet, were thrust eastward onto the Upper Yangtze terrane (equivalent to the Sichuan Basin) and western South China during the Late Triassic, forming an intracontinental foreland basin16,27. From the late Triassic to the early Cretaceous, this foreland basin continued to receive continental sediment during the waning of tectonism and the apparent decay of orogenic topography28,29. Consequently, a low-lying, long-wavelength topographic depression developed east of the Songpan-Ganzi and Yidun terranes16,30. On both flanks of this northeast-trending foredeep, low-relief bedrock surfaces were identified and hypothesised to represent a once-contiguous landscape20 (Fig. 1a). Extensive low-temperature thermochronological data from these surfaces consistently yield late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene cooling ages24,31–34 (Fig. 1a). Modelling of thermal histories from multiple thermochronologic systems revealed a long phase of slow cooling (~1 °C/Ma) from late Cretaceous to early Eocene time24,28,33,35,36 (red lines in Fig. 1b), suggested to reflect a period of tectonic stability prior to the India-Asia collision28,35. In contrast, moderate cooling rates of 5–10 °C/Myr during the same time period in the Qiangtang, eastern Lhasa, northern Qinling, and eastern Upper Yangtze terranes31,32,34,37,38 (blue lines in Fig. 1b) suggests modest to rapid exhumation consistent with sustained topographic relief. Such regional differences in erosion/exhumation rates could be explained by a large-scale south-flowing river system, the main axis of which followed the foredeep depozone between eastern Tibet and South China (Fig. 2c), as argued by Deng et al.16.

Provenance signature of sedimentary basins

The late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene strata exposed in the investigated basins along the foredeep depozone (i.e., SW Sichuan, Xichang, Huili and Chuxiong basins; Fig. 1a) represent the youngest terrestrial clastic deposits at the eastern margin of Tibet, except for spatially limited Quaternary sediments25. The late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene age of the sedimentary rocks is based on diagnostic fossil assemblages (mainly ostracodes and charophyta) and on the youngest U-Pb ages from zircon age populations (see Supplementary Note).The deposits are consistently characterised by red, thick-bedded, fine- to medium-grained sandstone interbedded with siltstone and mudstone. Minor conglomerates are restricted to the Dujiangyan area (Supplementary Fig. 1). Evaporite-bearing sequences are rare, although lacustrine-dominated sequences were deposited during arid climate conditions (Supplementary Note), which implies that flow discharge was relatively high and likely maintained an interconnected drainage network3. Thick sandstone beds in the sandstone-rich subsection are lenticular or tabular with erosional contacts and are laterally continuous over scales of tens to hundreds of metres. Cross stratification, parallel bedding and upward fining trend are common within individual sandstone bed, which are interpreted as fluvial deposits5,16,25,26 (see Supplementary Note for details). Sandwiched mudstone and siltstone layers contain desiccation cracks, calcareous nodules and occasionally small-scale ripple marks, likely representing floodplain deposits5 (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note). Such fluvial-lacustrine facies association has been ascribed to be typical of the deposits of hydrologically open lakes associated with perennial river systems39,40, which makes the existence of a large throughgoing river system much likely. Palaeocurrent indicators reinforce this interpretation, showing a dominantly southward and southeastward flow direction16,30. The biofacies records in these basins provide further evidence. It shows that the fossil is dominated by ostracodes, freshwater lamellibranchia, fish specie and plant fossil which are diagnostic paleontological assemblages in many other hydrologically open lakes39,40.

Petrographic analysis of basin strata shows that all K2–E1 samples contain abundant quartz grains, sedimentary and metamorphic rock fragments, but lack fragments derived from volcanic rocks (Supplementary Fig. 2), suggesting mature sandstone compositions. On quartz-feldspar-lithic grain diagrams, most samples plot in the recycled orogenic provenance fields, except for five samples from Leshan area, which plot near the boundary between continental block and recycled orogen, typical of sandstones deposited in a tectonically stable continent. Heavy mineral spectra from all samples are similar and dominated by stable minerals, including magnetite, haematite, zircon and leucoxene, and all lack readily weathered minerals (Supplementary Fig. 3). This pattern is consistent with the abundance of quartz and sedimentary lithic fragments, suggesting that the deposits were mainly recycled from older sedimentary rocks.

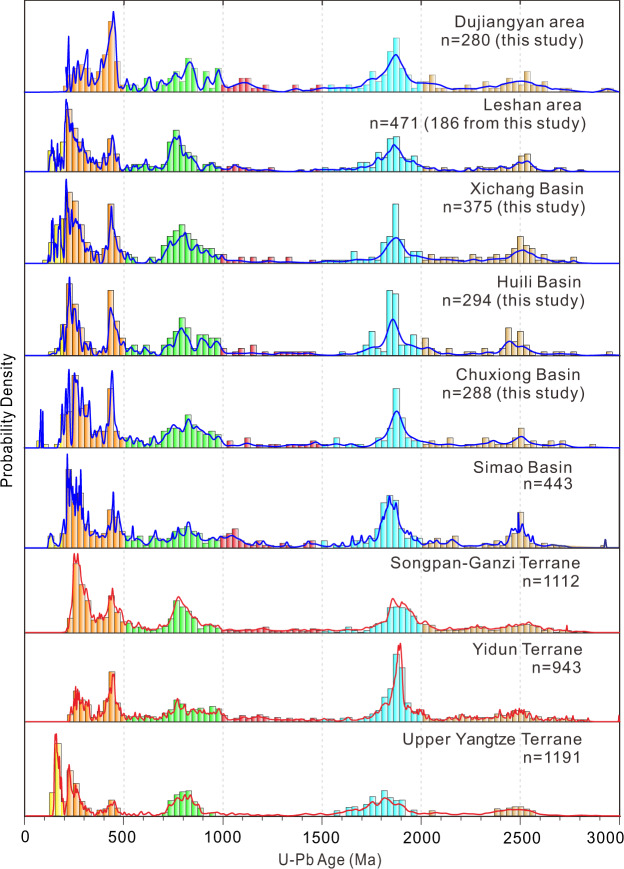

Multiple statistical methods that we applied to the zircon U-Pb age distributions (probability density function plots, multidimensional scaling (MDS), DZStats, and DZMix modelling; see Methods) indicate a high similarity between all studied basins. Zircon age populations from the basins fall mainly into five groups: ca. 200–300 Ma, 390–480 Ma, 700–900 Ma, 1700–2000 Ma, and 2300–2600 Ma (Fig. 3). The overall age patterns are similar to those of the Triassic flysch in the Songpan-Ganzi and Yidun terranes, and to the pre-late Cretaceous strata in the Upper Yangtze terrane (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4). DZstats results show that the zircon age components of all K2–E1 samples are statistically consistent, and share a statistically significant similarity to those of the Songpan-Ganzi, Yidun, and Upper Yangtze terranes (Supplementary Table 1). DZMix modelling also indicate principal contributions from the Songpan-Ganzi, Yidun, and/or the Upper Yangtze terranes into the studied basins (Supplementary Fig. 5). These similarities are also expressed in the MDS results. Samples from K2–E1 strata all cluster near the source samples of the three terranes mentioned above in the MDS plot (Supplementary Fig. 6). Moreover, modern sand samples from the Jinsha and Minjiang rivers, which drain these terranes, have zircon age distributions that also resemble those of the K2–E1 rocks (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 6).

Fig. 3. Zircon U-Pb data of late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene strata and potential source regions.

Zircon U-Pb data are from this study and were compiled from refs. 14,29,30,43. Data of potential source areas are from refs. 14,30 and references therein. Blue and red lines represent normalised probability density functions of detrital zircon samples from late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene strata and potential source regions, respectively. Histograms are binned at 30 Ma intervals. n indicates number of concordant U-Pb ages. Source data information of this study is provided in Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Data 2.

The consistent provenance signal from the different basins argue for the existence of a continuous fluvial system during the late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene. We attribute minor variations of the age groups in the different areas to the spatial heterogeneity of sediment dispersal systems (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figs. 4, 5 and 7). Age spectra from the Dujiangyan area are similar to that of Triassic flysch in the Songpan-Ganzi terrane; the absence of ages <200 Ma suggests a negligible input from the Upper Yangtze terrane. The young zircon population in the Leshan area and Xichang basin has a prominent peak at ca. 210–240 Ma, but contains distinct ages of <200 Ma as well, suggesting a mixture of material from the Songpan-Ganzi and Upper Yangtze terranes. To the south, zircon populations from the Huili Basin exhibit a decrease in the Upper Yangtze terrane signal (i.e., <200 Ma age peak) and an increased proportion of 1700–2000 Ma zircons compared to the Xichang Basin, reflecting an additional source from the Songpan-Ganzi or Yidun terranes. The provenance signal of the Chuxiong Basin changes little compared to the basins farther north, although a few late Cretaceous zircons suggest a minor source in the tectonically active Lhasa terrane, which was likely connected to the Neo-Tethyan Ocean by an external drainage system31,41. Alternatively, the Lhasa terrane may have been drained by several independent river systems during the late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene.

Discussion

Existence of a continental-scale palaeo-drainage system

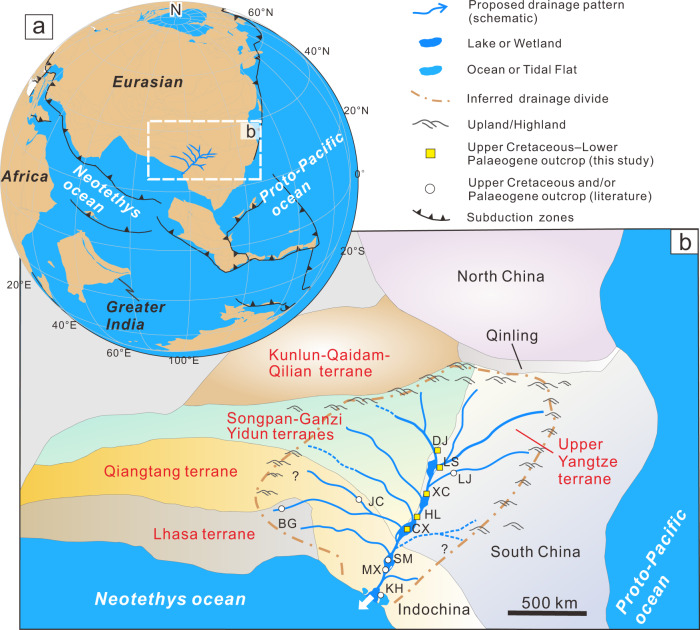

We interpret our sediment-provenance data to support the existence of a late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene river system, which flowed southwards and was successively joined by tributaries from the Songpan-Ganzi, Yidun, and Upper Yangtze terranes, and from eastern Tibet (Fig. 4). Although local rivers from these source regions could display similar provenance signals, the abundance of several metres to tens of metres thick fluvial sand bodies, the scarcity of proximal-facies sediments, and the prolonged slow exhumation of the regions surrounding these basins, suggest that the K2–E1 sediments were not deposited in spatially separated endorheic basins. If these sediments were derived locally, widespread Neoproterozoic granitic rocks at the western margin of the South China Block42 would provide a prominent source of detrital material for all studied basins, and a prominent peak at 700–900 Ma would be expected. However, our samples are characterised by multimodal age spectra of detrital zircons (Fig. 3), thus supporting the existence of a single large-scale river system. The envisaged palaeo-river system followed the pre-existing foredeep depozone of the late Triassic–early Cretaceous foreland basin (Figs. 1a and 4). Other large rivers on Earth, such as the modern Yellow River, the Nile River, and the Amazon River also flow along ancestral structural lows1,2,5, which can sustain the longevity of drainage systems1,5.

Fig. 4. Schematic reconstruction of paleogeography before the India-Asia collision.

a Plate reconstruction of East Asia during the latest Cretaceous (generated from Müller et al. 68). b Reconstruction of the late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene drainage system in eastern Tibet based on this study. KH Khorat Basin, MX Muang Xai Basin, LJ Liujia Section, JC Jianchuan Basin, BG Bangoin. Other abbreviations as in Fig. 1.

When considered in a broader context, the K2–E1 deposits in the Simao Basin14,43 and Muang Xai Basin44 farther south and those from the Sichuan Basin to the Chuxiong Basin, which all exhibit similar zircon U-Pb age distributions (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 8), also require a highly-connected sediment transport pathway. This interpretation, along with the lack of K2–E1 terrestrial deposits in the western South China Sea13,15, favours our palaeo-drainage reconstruction into the Neo-Tethyan Ocean (Fig. 4). A consistently south-directed paleocurrent from the sandstone bodies in the late Cretaceous units of the southernmost Khorat Basin provides additional physical evidence for this sediment transport pathway45,46. Furthermore, the widespread occurrence of late Cretaceous to early Palaeogene marine evaporites in the Simao and Khorat Basins47,48 implies that these areas were close to sea level. Although some studies inferred that paleoseawater likely originated from the northwest (e.g., the proto-Paratethys Sea; Wang et al.49), this recharge model cannot explain the observation that late Cretaceous marine deposits were absent between the Qiangtang and the Simao–Khorat Basins47. Rather, the pronounced southward thickening trends of the evaporite marker intervals50, together with the terrestrial palaeogeographic reconstruction of East Asia spanning the late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene transition (e.g., Poblete et al.51) likely argue for a transgression of the Neo-Tethyan Ocean from the south or southwest (e.g., refs. 48,50). Similar backwater effects extending hundred of kilometres inland can also be observed in the lower reaches of modern continental-scale river systems (e.g., Mississippi and Amazon rivers), where saltwater intrusions occur frequently52. Our interpretation of a connection between the Simao–Khorat Basins and the Neo-Tethyan does not preclude a more complex drainage configuration, potentially involving the assembly of multiple circuitous channels draining to the seaway. Additional sedimentary facies identification and systematic provenance analyses from K2–E1 strata in the Khorat basin and surrounding area, specifically for fluvial-deltaic and deep-water deposits, are necessary to fully explore this hypothesis. For example, in Borneo south of Khorat, a Mississippi-scale submarine fan system persisted throughout late Cretaceous–early Cenozoic time53 (Supplementary Fig. 8), leaving open the possibility that the sediment delivery system may have distally extended into deepwater areas. It is also possible that the paleo-drainage network discharged into the Neo-Tethyan Ocean during the late Cretaceous and Palaeocene, but later changed its course as a result of the India-Asia collision, and flowed into the proto-South China Sea starting in late Eocene.

Implications for landscape evolution

The existence of a large river system that persisted for tens of millions of years intrinsically reflects a prolonged period of tectonic stability and a relatively stable base level prior to the India-Asia collision and plateau uplift in eastern Tibet28,35. That these preconditions are met is indicated by the slow cooling rates from low-temperature thermochronology (Fig. 1b) and a slowly rising global sea level during K2–E154. Due to its intercontinental setting, the region was prone to the generation of a low-relief landscape. Similar landscapes that formed in tectonically stable settings by slow erosion over tens to hundreds of millions of years are present in central Australia55 and Mongolia56.

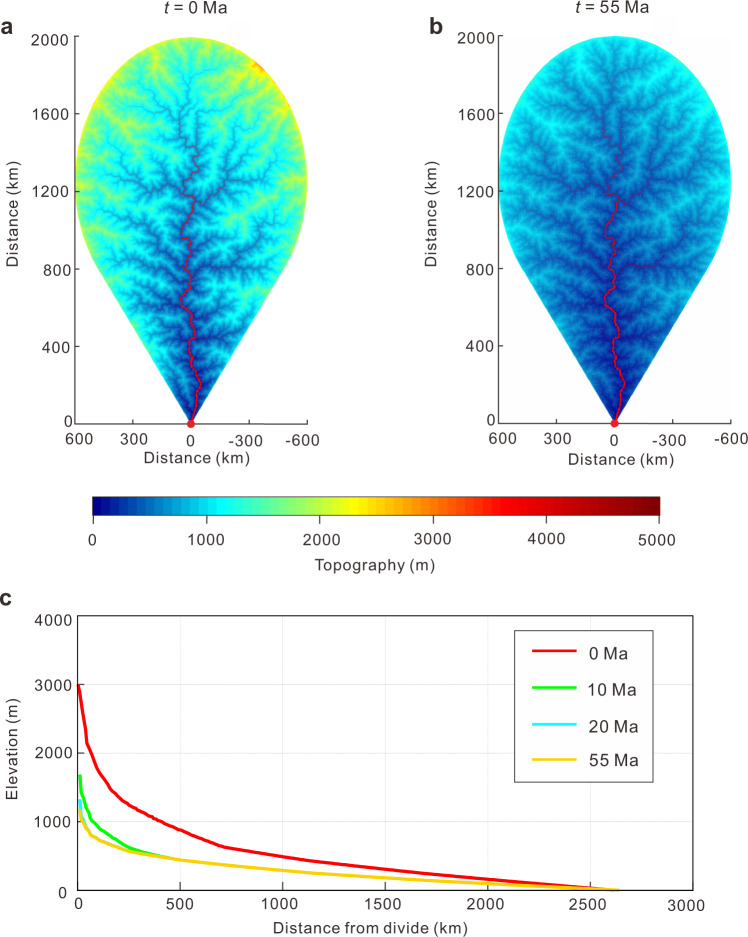

A simple landscape evolution model confirms that the envisioned mechanism for generating the low-relief landscape is feasible (see Methods section). In our model, a 2000 × 1200 km drainage system with an initial relief of 3000 m (broadly constrained by structural data on crustal thickening in central Tibet57) is eroded by river incision and hillslope diffusion while being slowly uplifted at a rate of 40 m Myr−1. After ~20 Ma, the total relief of the model is reduced to <1000 m and a low-relief landscape has formed (Fig. 5). Lateral channel migration and long-term continental weathering would further help to reduce topographic relief through time (cf., refs. 56,58). In turn, decreased basin subsidence and reduction of drainage divides during the late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene led to overfill of these basins, also allowed the transcontinental river system to be entrenched.

Fig. 5. Results of landscape evolution models illustrating the decay of relief over ~55 Ma.

a Initial relief is 3000 m at 0 Ma. b Topographic relief is reduced to a regional low-relief topographic surface (< 1000 m) after 55 Ma. c Modelled change in elevation along the longitudinal profile of the trunk river from the continental interior to base level at 0 Ma, 10 Ma, 20 Ma and 55 Ma. Model parameters are given in Supplementary Table 2.

Our conclusion that the low-relief landscape observed in eastern Tibet today formed at relatively low elevation is consistent with available palaeo-altimetric data, which indicate that most areas of eastern and southeastern Tibet were close to sea level before the middle Eocene59,60. Abundant low-relief landscape patches preserved north and south of the Ailaoshan–Red River shear zone61 (Fig. 1a) indicate that this regional low-relief surface developed from the Tibetan hinterland to the Neo-Tethyan Ocean before the Ailaoshan–Red River shear zone was formed in the late Eocene (e.g., Gilley et al. 62). Collectively, the arguments listed above show that a continental-scale river system existed during the late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene. This river system likely formed a low-relief landscape, which was uplifted and incised during Late Cenozoic deformation and uplift of the eastern Tibetan Plateau10,63,64.

Methods

Petrography

A total of twenty-two samples were collected from four (sub-) basins for thin section petrographic analysis (see Supplementary Table 3 for GPS data of samples). For each sample, at least 400 framework sand grains were identified and counted under the microscope. The results were plotted on ternary diagrams according to the Gazzi-Dickinson point-counting method69,70. Several kinds of provenance and component fields were established according to different mineral assemblages, including total quartz-feldspar-lithics (Q-F-L), volcanic and metamorphic lithic fragments-carbonate lithic fragments-terrestrial sedimentary clastic (Lv+Lm-Lc-Ls), and metamorphic lithic fragments-terrestrial sedimentary clastic-volcanic lithic fragments (Lm-Ls-Lv).

Heavy mineral analysis

Heavy minerals are defined as components with a density of more than ~2.9 g/cm3 in detrital rock. We collected a total of 22 bulk samples from four (sub-) basins for heavy minerals analysis. Each sample consisted of 2–3 kg of fine to medium-grained sandstone. To obtain heavy mineral grains, bulk samples were crushed and clay and silt particles were removed. The remaining material of the 0.0625–0.5 mm grain-size fraction was washed using aluminium round wandering disc. The extracted minerals were separated and identified by magnetic, electrostatic filters and heavy liquid of tribromomethane. To avoid a sampling bias, ~1000 heavy mineral grains were point-counted with regular spaced points.

Detrital zircon geochronology

In this study, we present 1423 new detrital zircon U-Pb ages from 14 late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene samples: five from the southwestern Sichuan basin (CX-02, CX-03, CX-07, CX-14, CX-19), three from the Xichang basin (CX-23, CX-24, CX-25), three from the Huili basin (CX-30, CX-31, CX-32) and three samples are from the Chuxiong basin (CX-34, CX-35, CX-36) (for detailed source data see Supplementary Data 1 and 2).

Zircon U-Pb dating was done at the State Key Laboratory of Earthquake Dynamics, Institute of Geology, China Earthquake Administration using laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS). At least 200 zircon grains were randomly selected to adhere to double-sided adhesive, and were poured into the laser sample target with epoxy resin. All samples were ablated by using a laser beam with a diameter of 28 μm, a frequency of 10 Hz and laser energy density of 4.0 J/cm2. The zircon 91500 and GJ-1 standards were analysed every 10 grains, and were used as monitoring standards; element concentrations were determined using NIST610 as external standard and 29Si as internal standard (once every ten measuring points). For a detailed description of the methodology, equipment, and analytical procedures we refer to Yuan et al.71. The data were processed using the Glitter 4.0 software, whereas the common lead correction method followed Andersen72. To test the robustness and reliability of the results, the zircon U-Pb dating of samples CX-25-2, CX-31-2 and CX-36 were carried out at the Nanjing Normal University, zircon standard 91500 and Qinghu were used for external correction. The external standard zircons of 91500, GJ-1 and Qinghu yielded 206Pb/238U weighted ages of 1062.5 ± 1 Ma (n = 212), 604.6 ± 2 Ma (n = 137) and 159.9 ± 0.83 Ma (n = 34), respectively. These are consistent with reference ages of 1063.1 ± 8.1 Ma (91,500, Yuan et al.71), 600.9 ± 3.1 Ma–610 ± 1.7 Ma (GJ-1, refs. 73,74) and 159 ± 0.2 Ma (Qinghu, ref. 75). We apply a <10% discordance filter to the generated data. For zircon grains older than 1100 Ma, the best age was determined from 207Pb/206Pb ratio71; while for those younger than 1100 Ma, the best age was calculated from 206Pb/238U ratio71. In this study, all samples from the different basins show consistent detrital zircon components, and each sample yielded 68–123 concordant ages, which generally meets statistical requirements (Vermeesch76).

In order to objectively evaluate the similarities and differences of the zircon U-Pb age distributions between samples, we utilised multidimensional scaling analysis (MDS) and DZStats77,78. MDS is a robust and flexible principal components analysis (PCA) which makes fewer assumptions about the data, produces a “map” of points on which “similar” samples cluster closely together, whereas “dissimilar” samples plot farther apart. The calculations were carried out using the mdscale function of the Statistics Toolbox77. A MDS map can clearly visualise the ‘dissimilarities’ between the detrital zircon samples. The details about the MDS method are available in Vermeesch77. We also quantitatively distinguish the similarity between samples using DZstats, a quantitative MATLAB-based method. DZstats is based on intersample comparisons to compute Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K–S) test D values and Kuiper test V values (see Saylor et al.78 for details). Two age distributions that yield low D from the K-S test or low V values from the Kuiper test imply that the two age spectra are nearly identical, whereas higher values have a larger probability of different parent populations.

Quantitative provenance analysis was also performed through the use of the DZMix modelling software based on Monte Carlo modelling79. This method allows an objective comparison between zircon U‐Pb age distributions of individual mixed samples (late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene samples in this study) and those of known sources, extracting a best-fit model of the mixed samples and determining the relative proportions of each potential source for individual samples. Full details are provided by ref. 79. In this study, we evaluate best-fit models using a D value from the K-S test between observed and modelled zircon age components. We note that this is a relatively new technique with potential uncertainties induced by the number of zircon grains, sediment recycling and similar characteristics of the sources. Thus, the combination of zircon U-Pb age probability density functions, heavy mineral assemblages, petrographic frameworks and palaeocurrent data is essential for our provenance study.

Landscape evolution simulation

To assess the feasibility of the low-relief landscape formation envisioned for our late Cretaceous–early Palaeogene drainage reconstruction, we built a simple landscape evolution model. The numerical domain covers a leaf-shaped region of 2000 × 1200 km (analogous to the scale of our reconstructed palaeo-drainage system) with closed boundary conditions, except for one open boundary node. We start our numerical experiments by proportionately increasing the digital elevation of a quasi-steady-state topography, which we define as a change in elevation of <10−5 m/a. This quasi-steady-state topography is generated by applying a random disturbance in elevation to a surface that is slightly tilted towards the main channel in the centre of the model. The initial total relief of the modelled domain is 3000 m. This value is estimated from structural data on crustal thickening in central Tibet before the India-Asia collision57.

The landscape evolution model includes river incision and hillslope processes. We employed the stream power model for river incision and a linear diffusion law for describing hillslope erosion:

| 1 |

In the equation above, z is elevation, t is time, Kd is the diffusive coefficient, Ks is the incision coefficient, A is the contributing drainage area, U is the spatially uniform uplift rate and m and n are empirical constants. Note that the river incision coefficient (Ks = 1.11 × 10−6 m0.1 per year) used in our simulation is the same that was obtained from the late Cenozoic Dadu River in eastern Tibet80. The values of all parameters used in our model are given in Supplementary Table 2.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) (2019QZKK0704), the NSF of China (41888101, 41622204), the Institute of Geology, CEA (IGCEA2003), and Innovation Group Project of Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (311021002). We thank Peter Molnar and Andrew Laskowski for thoughtful comments and suggestions, and Maodu Yan and Bin Deng for discussions on the age constraints and facies of basin sediments.

Author contributions

H.Z and X.Z designed the study. H.Z., X.Z., R.H., A.R.D., K.X.W., E.K., P.W. and P.Z. discussed early versions of the ideas presented here, which were refined following discussion among all authors. X.Z., J.X. and X.L conducted fieldwork. X.Z processed and analysed the data. X.Z., H.Z, Y.L., P.M. and B.Z created all figures. J.P., Y.W., P.W., J.Z. and K.L. assisted the zircon U-Pb dating. All authors contributed to the discussion and writing of the manuscript.

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Douglas Burbank, Andrew Laskowski and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

All data used in this study are available in the Supplementary Information and Supplementary Data files. The detrital zircon geochronological data have also been deposited in the Figshare database 10.6084/m9.figshare.13506954.v4

Code availability

The code used in landscape evolution simulation of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-27587-9.

References

- 1.Potter PE. Significance and origin of big rivers. J. Geol. 1978;86:13–33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shephard G, et al. Miocene drainage reversal of the Amazon River driven by plate–mantle interaction. Nat. Geosci. 2010;3:870–875. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng HB, et al. Pre‐Miocene birth of the Yangtze River. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:7556–7561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216241110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faccenna C, et al. Role of dynamic topography in sustaining the Nile River over 30 million years. Nat. Geosci. 2019;12:1012–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miall, A. D. The Geology of Fluvial Deposits: Sedimentary Facies, Basin Analysis, and Petroleum Geology, p. 362–365 (Springer, 2006).

- 6.Clark MK, et al. Surface uplift, tectonics, and erosion of eastern Tibet from large–scale drainage patterns. Tectonics. 2004;23:TC1006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis WM. The geographic cycle. Geogr. J. 1899;14:481–504. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brookfield ME. The evolution of the great river systems of southern Asia during the Cenozoic India–Asia collision: rivers draining southwards. Geomorphology. 1998;22:285–312. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hallet B, Molnar P. Distorted drainage basins as markers of crustal strain east of the Himalaya. J. Geophys. Res. 2001;106:13697–13709. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark MK, et al. Late Cenozoic uplift of south-eastern Tibet. Geology. 2005;33:525–528. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong P, et al. Cosmogenic nuclide burial ages and provenance of the Xigeda paleo‐lake: Implications for evolution of the Middle Yangtze River. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2009;278:131–141. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang R, et al. Early Pleistocene drainage pattern changes in Eastern Tibet: constraints from provenance analysis, thermochronometry, and numerical modeling. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2020;531:115955. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clift PD, et al. Evolving east Asian river systems reconstructed by trace element and Pb and Nd isotope variations in modern and ancient Red Rive-Song Hong sediments. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2008;9:Q04039. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, et al. Detrital zircon U‐Pb geochronological and sedimentological study of the Simao Basin, Yunnan: implications for the early Cenozoic evolution of the Red River. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2017;476:22–33. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C, et al. Provenance and drainage evolution of the Red River revealed by Pb isotopic analysis of detrital K‐feldspar. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019;46:6415–6424. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng B, et al. Heavy mineral analysis and detrital U-Pb ages of the intracontinental Palaeo-Yangtze basin: Implications for a transcontinental source-to-sink system during Late Cretaceous time. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2018;130:2087–2109. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang ZJ, et al. Sedimentary provenance constraints on drainage evolution models for SE Tibet: Evidence from detrital K-feldspar. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017;44:4064–4073. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wissink GK, Hoke GD, Garzione CN, Liu ZJ. Temporal and spatial patterns of sediment routing across the southeast margin of the Tibetan Plateau: Insights from detrital zircon. Tectonics. 2016;35:2538–2563. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang R, Willett SD, Goren L. In situ low-relief landscape formation as a result of river network disruption. Nature. 2015;520:526–529. doi: 10.1038/nature14354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark MK, et al. Use of a regional, relict landscape to measure vertical deformation of the eastern Tibetan plateau. J. Geophys. Res. 2006;111:F03002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whipple KX, DiBiase RA, Ouimet WB, Forte AM. Preservation or piracy: Diagnosing low-relief, high-elevation surface formation mechanisms. Geology. 2017;45:91–94. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao L, Shao L, Qiao P, Zhao Z, van Hinsbergen DJJ. Early Miocene birth of modern Pearl River recorded low-relief, high-elevation surface formation of SE Tibetan Plateau. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2018;496:120–131. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu-Zeng J, Tapponnier P, Gaudemer Y, Ding L. Quantifying landscape differences across the Tibetan Plateau: implications for topographic relief evolution. J. Geophys. Res. 2008;113:F04018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang HP, et al. Pulsed exhumation of interior eastern Tibet: implications for relief generation mechanisms and the origin of high-elevation planation surfaces. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2016;449:176–185. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sichuan Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources. Regional Geology of Sichuan Province h.11&12 (part I): 264–282 (Geological Publishing House, 1991).

- 26.Yunnan Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources. Regional Geology of Yunnan Province Ch.11&12 (part I): 222–253 (Geological Publishing House, 1990).

- 27.Burchfiel BC, Chen Z. Tectonics of the southeastern tibetan plateau and its adjacent foreland. Geol. Soc. Am. Mem. 2012;210:231. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roger F, Jolivet M, Cattin R, Malavieille J. Mesozoic-Cenozoic Tectonothermal evolution of the eastern part of the Tibetan Plateau (Songpan-Garzê, Longmen shan area): Insights from thermochronological data and simple thermal modelling. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2011;353:9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li YQ, et al. Sedimentary provenance constraints on the Jurassic to Cretaceous paleogeography of Sichuan Basin, SW China. Gondwana Res. 2018;60:15–33. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang HY, He DF, Li D, Li YQ. Detrital zircon U-Pb ages of Palaeogene deposits in the southwestern Sichuan foreland basin, China: Constraints on basin-mountain evolution along the southeastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2020;130:2087–2109. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hetzel R, et al. Peneplain formation in southern Tibet predates the India-Asia collision and plateau uplift. Geology. 2011;39:983–986. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai JG, Wang CS, Hourigan J, Santosh M. Insights into the early Tibetan Plateau from (U–Th)/He thermochronology. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 2013;170:917–927. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tian YT, Kohn BP, Gleadow AJW, Hu SB. A thermochronological perspective on the morphotectonic evolution of the southeastern Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. 2014;119:676–698. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Z, et al. Sichuan Basin and beyond: eastward foreland growth of the Tibetan Plateau from an integration of Late Cretaceous-Cenozoic fission track and (U-Th)/He ages of the eastern Tibetan Plateau, Qinling, and Daba Shan. J. Geophys. Res. 2017;122:4712–474. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirby E, et al. Late Cenozoic evolution of the eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau: Inferences from 40Ar/39Ar and (U-Th)/He thermochronology. Tectonics. 2002;21:1001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao K, et al. Thrusting, exhumation, and basin fill on the western margin of the South China block during the India-Asia collision. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2021;133:74–90. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rohrmann A, et al. Thermochronologic evidence for plateau formation in central Tibet by 45 Ma. Geology. 2012;40:187–190. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi HC, Shi XB, Glasmacher UA, Yang XQ, Stockli DF. The evolution of eastern Sichuan basin, Yangtze block since Cretaceous: constraints from low temperature thermochronology. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2016;116:208–221. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carroll AR, Bohacs KM. Stratigraphic classification ofancient lakes:balancing tectonic and climatic controls. Geology. 1999;27:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bohacs, K. M., Carroll, A. R., Neal, J. E. & Mankiewicz, P. J. Lake Basins Through Space and Time (eds. E. H. Gierlowski-Kordesch and K. R. Kelts) Vol. 46, p. 3–34 (American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 2000).

- 41.Haider VL, et al. Cretaceous to Cenozoic evolution of the northern Lhasa Terrane and the early Paleogene development of peneplains at Nam Co, Tibetan Plateau. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2013;71:79–98. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li ZX, et al. Geochronology of Neoproterozoic syn-rift magmatism in the Yangtze craton, South China and correlations with other continents: evidence for a mantle superplume that broke up Rodinia. Precambrian Res. 2005;122:85–109. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang LC, Liu C, Gao X, Zhang H. Provenance and paleogeography of the Late Cretaceous Mengyejing Formation, Simao Basin, southeastern Tibetan Plateau: Whole-rock geochemistry, U-Pb geochronology, and Hf isotopic constraints. Sediment. Geol. 2014;304:44–58. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang YL, et al. Provenance and paleogeography of the Mesozoic strata in the Muang Xai basin, northern Laos: petrology, whole-rock geochemistry, and U–Pb geochronology constraints. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2017;106:1409–1427. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heggemann H, Helmcke D, Tietze KW. Sedimentary evolution of the Mesozoic Khorat basin in Thailand. Zbl. Geol. Palaont. Teil. 1992;1:1267–1285. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singsoupho S, Bhongsuwan T, Elming SÅ. Palaeocurrent direction estimated in Mesozoic redbeds of the Khorat Plateau, Lao PDR, Indochina Block using anisotropy of magnetic susceptibility. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015;106:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qin Z, et al. Origin and recharge model of the late cretaceous evaporites in the khorat plateau. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020;116:103226. [Google Scholar]

- 48.El Tabakh M, Utha-Aroon C, Schreiber BC. Sedimentology of the Maha Sarakham evaporites in the Khorat Plateau of northeastern Thailand. Sediment. Geol. 1999;123:31–62. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang LC, Zhong YS, Xi DP, Hu JF, Ding L. The Middle to Late Cretaceous marine incursion of the Proto-Paratethys sea and Asian aridification: a case study from the Simao-Khorat salt giant, southeast Asia. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2021;567:110300. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yan MD, et al. New Insights on the age of the Mengyejing formation in the Simao basin, SE Tethyan domain and its geological implications. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2021;64:231–252. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poblete F, et al. Toward interactive global paleogeographic maps, new reconstructions at 60, 40 and 20 Ma. Earth Sci. Rev. 2021;214:103508. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blum M, Martin J, Milliken K, Garvin M. Paleovalley systems: Insights from Quaternary analogs and experiments. Earth Sci. Rev. 2013;116:128–169. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galin T, Breitfeld HT, Hall R, Sevastjanova I. Provenance of the Cretaceous–Eocene Rajang Group submarine fan, Sarawak, Malaysia from light and heavy mineral assemblages and U-Pb zircon geochronology. Gondwana Res. 2017;51:209–233. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller KG, et al. The phanerozoic record of global sea-level change. Science. 2005;310:1293–1298. doi: 10.1126/science.1116412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stewart AJ, Blake DH, Ollier CD. Cambrian river terraces and ridgetops in central Australia: Oldest persisting landforms? Science. 1986;233:758–761. doi: 10.1126/science.233.4765.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jolivet M, et al. Mongolian summits: an uplifted, flat, old but still preserved erosion surface. Geology. 2007;35:871–874. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murphy MA, et al. Did the Indo-Asian collision alone create the Tibetan plateau? Geology. 1997;25:719–722. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Osborn G, Toit CD. Lateral planation of rivers as a geomorphic agent. Geomorphology. 1991;4:249–260. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang KJ. Cretaceous palaeogeography of Tibet and adjacent areas (China): Tectonic implications. Cretac. Res. 2000;21:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoke GD, Liu-Zeng J, Hren MT, Wissink GK, Garzione CN. Stable isotopes reveal high southeast Tibetan Plateau margin since the Palaeogene. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2014;394:270–278. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schoenbohm L, Whipple K, Burchfiel BC. River incision into a relict landscape along the Ailao Shan shear zone and Red River fault in Yunnan Province, China. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2004;116:895–909. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gilley LD, et al. Direct dating of left-lateral deformation along the Red River shear zone, China and Vietnam. J. Geophys. Res. 2003;108:2127. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang E, et al. Two-phase growth of high topography in eastern Tibet during the Cenozoic. Nat. Geosci. 2012;5:640–645. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Godard V, et al. Late Cenozoic evolution of the central Longmen Shan, eastern Tibet: Insight from (U-Th)/He thermochronometry. Tectonics. 2009;28:TC5009. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gourbet L, et al. Evolution of the Yangtze River network, southeastern Tibet: Insights from thermochronology and sedimentology. Lithosphere. 2020;12:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nie J, et al. Rapid incision of the Mekong River in the middle Miocene linked to monsoonal precipitation. Nat. Geosci. 2018;11:944–948. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Y, et al. Cenozoic exhumation of the Ailaoshan‐Red River shear zone: new insights from low‐temperature thermochronology. Tectonics. 2020;39:e2020TC006151. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Müller RD, et al. A global plate model including lithospheric deformation along major rifts and orogens since the Triassic. Tectonics. 2019;38:1884–1907. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dickinson WR, et al. Provenance of North American Phanerozoic sandstones in relation to tectonic setting. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1983;94:222–235. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ingersoll RV, et al. The effect of grain size on detrital modes: a test of the Gazzi-Dickinson point-counting method. J. Sediment Pet. 1984;54:103–116. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yuan HL, et al. Accurate U-Pb age and trace element determinations of zircon by laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 2004;28:335–370. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Andersen T. Correction of common lead in U-Pb analyses that do not report 204Pb. Chem. Geol. 2002;192:59–79. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eelhlou S, et al. Trace element and isotopic composition of GJ red zircon standard by laser ablation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2006;70:A158. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jackson SE, Pearson NJ, Griffin WL, Belousova EA. The application of laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry to in situ U-Pb zircon geochronology. Chem. Geol. 2004;211:47–69. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li X, et al. Qinghu zircon: a working reference for microbeam analysis of U-Pb age and Hf and O isotopes. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2013;58:4647–4654. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vermeesch P. How many grains are needed for a provenance study? Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2004;224:351–441. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vermeesch P. Multi-sample comparison of detrital age distributions. Chem. Geol. 2013;341:140–146. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Saylor JE, Sundell KE. Quantifying comparison of large detrital geochronology data sets. Geosphere. 2016;12:203–220. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sundell K, Saylor JE. Unmixing detrital geochronology age distributions. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2017;18:2872–2886. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ma Z, Zhang H, Wang Y, Tao Y, Li X. Inversion of Dadu River bedrock channels for the Late Cenozoic uplift history of the eastern Tibetan Plateau. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020;47:e2019GL086882. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are available in the Supplementary Information and Supplementary Data files. The detrital zircon geochronological data have also been deposited in the Figshare database 10.6084/m9.figshare.13506954.v4

The code used in landscape evolution simulation of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.