Abstract

Trust between healthcare workers is a fundamental component of effective, interprofessional collaboration and teamwork. However, little is known about how this trust is built, particularly when healthcare workers are distributed (i.e., not co-located and lack a shared electronic health record). We interviewed 39 healthcare workers who worked with proximal and distributed colleagues to care for patients with diabetic foot ulcers and analyzed transcripts using content analysis. Generally, building trust was a process that occurred over time, starting with an introduction and proceeding through iterative cycles of communication and working together to coordinate care for shared patients. Proximal, compared to distributed, dyads had more options available for interactions which, in turn, facilitated communication and working together to build trust. Distributed healthcare workers found it more difficult to develop trusting relationships and relied heavily on individual initiative to do so. Few effective tools existed at the level of interprofessional collaborations, teams, or broader healthcare systems to support trust between distributed healthcare workers. With increasing use of distributed interprofessional collaborations and teams, future efforts should focus on fostering this critical attribute.

Keywords: patient care team, referral and consultation, qualitative research, interprofessional, diabetic foot

Introduction

Effective collaboration and teamwork is facilitated by trust between healthcare workers (Baggs & Schmitt, 1997; Fiscella et al., 2017; Lynch, 2018). In turn, this work improves patient outcomes in a variety of disease states, including diabetes and cancer (Lynch, 2018; Noyes et al., 2016). Understanding how trust forms is increasingly important as collaboration and team complexity grows. Interprofessional collaboration and team composition is trending towards more healthcare workers, more professions, and distributed settings (Barnett et al., 2012; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2021; Noyes et al., 2016; Priest et al., 2006). However, we know very little about how healthcare workers build trust when working together and how the process might vary when healthcare workers are distributed (Fiscella et al., 2017; Frankel et al., 2019; Szafran et al., 2018). Understanding this process is the first step in supporting its development among healthcare worker dyads, interprofessional collaborations and teams, and broader healthcare systems. Enhancing trust between healthcare workers, especially those functioning in a distributed manner, should lead to improved teamwork and patient outcomes. In this paper, we define proximal healthcare worker dyads as those who were co-located and shared an electronic health record (EHR). Dyads who lacked one or both of these attributes were categorized as distributed. Our definition emerged from the data itself, but it very closely parallels that used in the systems engineering literature (Bell & Kozlowski, 2002; Fiore et al., 2003).

Background

Interprofessional care for patients with diabetic foot ulcers offers a unique lens through which to study how trust develops between healthcare workers. Interprofessional care has been associated with a reduced risk of major (above-ankle) amputation (Musuuza et al., 2020). These collaborations or teams, averaging five professions, have a clear unifying goal: limb salvage (Musuuza et al., 2020). Although the specific mix of healthcare workers on a given team varies, and non-physician members are under-reported, the following types of physicians are commonly involved: endocrinologists, infectious disease physicians, internists, peripheral vascular surgeons, and podiatrists (Musuuza et al., 2020). Many of these healthcare workers are based in different clinical settings with varying degrees of compatibility. The primary care provider and podiatrist are generally in proximity to each other. One of these two will spearhead care coordination, serially referring to other specialists as needed. These other specialists are typically distributed with respect to the primary care provider and podiatrist, such that interactions typically occur between only two healthcare workers at a time (Sutherland et al., 2020). This distribution can complicate healthcare worker (dyad) interactions, limiting the chances of achieving the shared goal (Davidow et al., 2018). Recognizing this pitfall, the aims of our study are to understand (a) how trust develops between multiple provider dyads caring for shared patients with diabetic foot ulcers, and (b) how this process differs for proximal and distributed dyads.

Methods

The current study is embedded within a larger investigation aiming to understand how primary care providers and specialists care for patients with diabetic foot ulcers (Sutherland et al., 2020). We chose a qualitative approach because little is known about how healthcare workers care for patients with diabetic foot ulcers, and what is important to this process. Naturalistic inquiry, in which people construct their own meaning and interpretations to processes that shape their reality, guided our methodology (Guba & Lincoln, 1982). The conceptual model underpinning the larger investigation describes how health system factors impact the process of providing interprofessional care and subsequent patient outcomes. Within the theme of health system factors was the concept of healthcare workers’ familiarity and confidence in each other’s abilities (Bartels et al., 2016). This concept allowed us to prospectively and explicitly query participants about how they built trust when working with other healthcare workers.

Participants

We recruited healthcare workers who cared for patients with diabetic foot ulcers throughout Wisconsin. Our goal was to interview participants until we achieved informational redundancy (Morse, 2000). We anticipated that interviewing 5-8 primary care providers and 10-20 other healthcare workers would be sufficient based on our prior qualitative work (Bartels et al., 2016; Brennan et al., 2015; Kolehmainen et al., 2014). We achieved information redundancy regarding the experiences of primary care providers after six interviews. However, the roles and experiences of other healthcare workers varied enough to necessitate expanding recruitment. We achieved informational redundancy after interviewing thirty-three other healthcare workers.

We began by purposefully recruiting rural primary care providers. Then, we used snowball sampling to identify other healthcare workers with whom they worked (Polit & Beck, 2012). This method was successful in recruiting other rural healthcare workers. However, it failed to identify those in urban referral centers; rural primary care providers collaborated with these individuals but did not know them well enough to suggest we contact them for study participation. Therefore, we began by hanging flyers in urban referral offices and sending recruitment emails. Once an urban healthcare worker was recruited, we again used snowball sampling to capture the breadth of professionals involved. Ultimately, study participants reflected a wide range of expertise, from physicians to referral coordinators and schedulers. Most worked with both proximal and distributed colleagues. All gave verbal informed consent for this study, which the Institutional Review Board approved for exemption (2018-0976).

Data Collection

A female interviewer (B.S.) conducted semi-structured interviews with each participant between September, 2018 and July, 2019 (average duration of interview: 49 minutes, range: 30-65 minutes). The interviewer had three years of qualitative health services research experience but no formal clinical experience. Although employed by the same healthcare organization as some urban healthcare workers, she did not interact with any study participants prior to the interviews. All interviews were conducted in-person, except one that was done by telephone. The interview guide was adapted from an existing conceptual model describing how health system factors directly impact the process of providing interprofessional care, and subsequently, patient outcomes (Bartels et al., 2016). It included the following questions related to trust:

When you work with other providers to take care of patients with diabetic foot ulcers, what helps to build trust?

What makes for a good response from a provider that you referred a patient to?

What causes conflict with other providers?

Each participant was compensated $100 cash at the conclusion of the interview.

Analysis

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by trained students listed in the acknowledgements. The interviewer (B.S.) compared the transcripts to the original audio recordings to ensure accuracy. We (B.S. and M.B.) initially analyzed transcripts using directed content analysis based on the conceptual model (Elo & Kyngas, 2008; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Our initial analysis aimed to understand how health system factors impact the process of interprofessional care and patient outcomes (Sutherland et al., 2020). During direct coding, trust between healthcare workers emerged as a new important theme. Therefore, we (B.S., M.B., and T.L.) revisited the raw data and used an inductive approach (conventional content analysis) to fully explore this theme (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). We independently coded the data and then discussed our findings (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Differencing in coding were resolved by consensus. All coding was performed using NVivo 12 (QRS International Inc., Burlington, MA).

Measures to Ensure Rigor

To verify dependability, or the reliability of data over time and conditions, we member-checked emerging themes related to trust (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Thirteen out of 39 participants responded to our member checking questions, all of whom endorsed our findings. Transferability, or the potential for our results to be extrapolated to other settings, was confirmed by a broader panel of rural healthcare workers who reviewed our emerging results. The panel was composed of members from the Rural Wisconsin Health Cooperative, which represents 44 different rural health systems throughout the state of Wisconsin. The group is dedicated to ensuring quality care, especially as it relates to diabetes, in rural settings. To ensure methodological rigor throughout the study, our team met regularly with the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research Qualitative Research Group to receive feedback on the design, data collection, and analysis. The group is composed of six to eight qualitative researchers from a number of different content areas who meet monthly to discuss methodologic aspects of each other’s work. They safeguarded the confirmability, or objectivity, of our findings.

Results

A total of 39 participants were recruited from seven healthcare systems (Table 1 near here). Of the seven systems, five were rural and two served as their urban referral centers. Regardless of their role, participants universally endorsed trust between healthcare workers as vital to quality interprofessional care. A vascular surgeon explained, “The more you work together, the more you know what they want, and they know what you want. You just have trust in each other.” Building trust between healthcare workers on interprofessional teams was a process that occurred over time, and differed based upon proximity.

Table 1.

Provider Roles and Proximity with Respect to the Referring Primary Care Provider (n=39)

| Participant role | Proximal (n) | Distributed (n) | Total (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care (physicians and APPsa) | Ref | Ref | 6 |

| Podiatry (podiatrists and medical assistant) | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Diabetes education (nurses and dietician) | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Wound care (physician, nurses, nurse case manager, medical assistant, hyperbaric oxygen technician) | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Home health (nurses) | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Infectious disease (physicians and APP) | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Administrative support (schedulers and referral coordinators) | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Vascular surgery (physicians, APP, nurses, and social worker) | 0 | 6 | 6 |

|

| |||

| Total | 9 | 23 | 39 |

Advanced Practice Providers

Defining Proximal and Distributed Healthcare Worker Dyads

Two systems-based factors influenced the process of building trust between healthcare workers: co-location and a shared electronic health record. Being in the same location and using the same electronic health record created a proximity that eased connectivity. In contrast, healthcare workers who lacked one or both of these criteria were considered distributed. They lacked the ability to easily connect with one another. The concept of proximal versus distributed dyads arose from observing two distinct patterns embedded within a general process of developing trust between healthcare workers.

General Process for Developing Trust

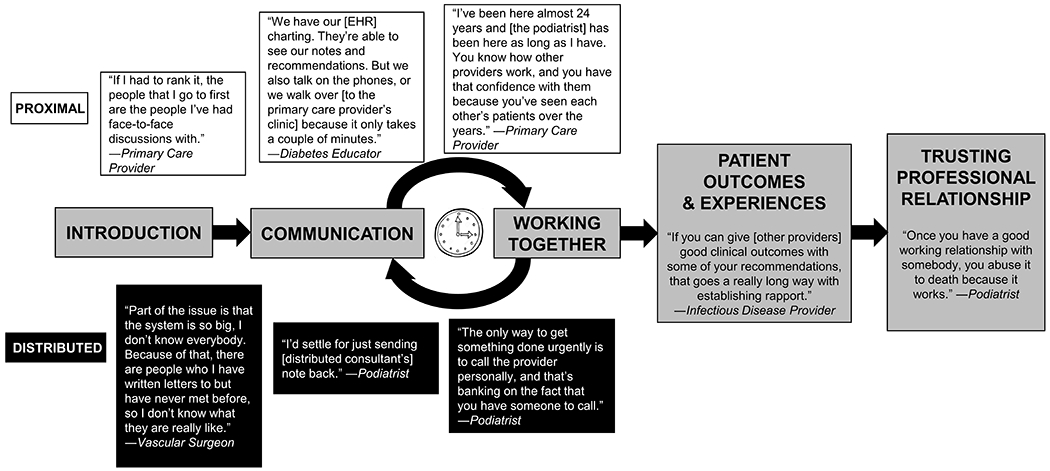

Regardless of whether they were proximal or distributed, healthcare workers developed trust through a series of generalizable steps (Figure). The process included: (a) an introduction, either prior to, or during, the referral process, (b) communication, which coordinated care for a patient, and (c) working together. The latter two steps were iterative and took time to result in trust between healthcare workers (Table 2 near here). Proximity influenced all three steps, which explicitly involved interactions between healthcare workers. However, proximity did not influence the final contributor to the development of trust: patient outcomes and experiences.

Figure.

Conceptual Model Outlining the General Process of How Provider-to-Provider Trust is Built, and Quotations Highlighting How this Process Differs Based on Proximity.

Table 2.

Major Themes with Supporting Quotations

| Theme | Supporting Quotations |

|---|---|

| Communication | “Communication is key. Keeping it open, so they know what we’re doing, and we know what they’re doing. I think that will bring trust.” – Podiatrist |

| “Just a willingness to communicate [helps build trust].” – Primary care provider | |

| “When you get to know each other, then you have each other’s cell phone numbers and you can start texting…That’s better because then you can start to trust.” - Podiatrist | |

|

| |

| Working together | “Being in a small community, you work very closely together. And you build trust that way.” – Wound clinic physician’s assistant |

| “The culture of trust comes from experience and working together.” – Vascular surgery physician’s assistant | |

|

| |

| Fulfilling individual provider responsibility | “They trust me. They know I’ll work on it.” – Referral coordinator |

| “The biggest way to build trust is to prove you know what you’re doing.” – Home health nurse | |

|

| |

| Timeliness | “Seeing that pattern from referring doctors builds up a good level of trust, especially if they consult in a timely fashion.” – Vascular surgeon |

| “When someone says ‘I’ll start working on that right away,’ and they follow through, that’s huge for me. Timeliness. That’s what builds our trust.” – Referral coordinator | |

|

| |

| Responsiveness | “Why do they trust me? It’s because I listen.” – Nurse case manager |

| “I think [trust] is a two-way street. You know what your needs are, what you need from us, and vice versa. If they call and say, ‘Hey, we have a patient who really needs to get in.’ OK, we will do it. We will get them in. If they are going to be seeing a different provider that same day, can we work with the appointments? We can move ours, you can move yours. We kind of figure out what is the least amount of effort.“ – Wound clinic staff | |

|

| |

| Time | “I think that I’ve gained their trust over the years. They know I’m taking good care of their patients. So yeah, we do have a team.” – Wound care nurse |

| “Having a lot of mutual patients together, over time, helps build trust, too.” – Vascular surgeon | |

| “I think [trust] just comes from time, repetition.” – Home health nurse | |

Communication and working together were distinct but inter-related themes, and less straightforward than those of introductions and patient experiences. Communication involved what information was exchanged, and how (e.g., calls or notes). All healthcare workers emphasized that good communication involved outlining a detailed care plan and explicitly defining healthcare worker roles. One primary care provider described the need for detailed care plans:

Being clear about what follow up is going to happen. Is it going to happen with [the consultant], or do they want the patients to follow up with the [primary care provider]? If there’s a wound, then who is going to be changing the dressings? How often should they change the dressings? Really thorough notes on what exactly should be happening is key.

Although information needs were consistent, how information was communicated varied between proximal and distributed dyads.

Working together was supported by, but distinct from, communication. It encompassed other aspects of collaboration and teamwork, including fulfilling individual responsibilities, responsiveness, timeliness, and not over-stepping professional bounds. A nurse commented on the importance of individual healthcare workers responsibilities in building trust, “Pulling your own weight— that’s huge.” Referring healthcare workers also were attuned to the general responsiveness of their consultants. One nurse case manager voiced, “For me, trust building comes when I’m talking on the phone, and you can hear if people are interested.” Nearly all healthcare workers endorsed the significance of timeliness. One primary care provider defined a good response from a consultant as “Timeliness. Seeing the patient and addressing the patient’s and my concerns in a timely fashion.” A wound care nurse described the importance of not over-stepping bounds: “Definitely sharing the notes back, so that [the referring healthcare worker] can see that the patient is getting better, and also that we’re keeping the patient with them. We’re not taking over everything. I think that’s important.” Although the expectations for working together were the same for proximal and distributed dyads, differences in communication challenged distributed dyads to fulfill these standards. These differences are contrasted in the following two subsections and Figure.

Building Trust with Proximal Healthcare Workers

When healthcare workers were proximal to one another, introductions were most often made face-to-face, which initiated the process of building trust. Introductions occurred one-on-one and in groups. An administrative support staff member recounted “When I first started here, providers would walk right past me and go to the people that they knew and were familiar with. I had to establish, ‘I can help you with whatever you need.’” One podiatrist used grand rounds as a platform to introduce herself to healthcare workers in the hospital: “I’ve tried to do lectures at least twice a year to let [others] know what my scope of practice is.” These face-to-face introductions functioned to establish a sense of familiarity.

Communication in the proximal setting took many forms, including EHR-based and direct communication. At a minimum, communication consisted of carbon copying (cc’ing) healthcare workers on one another’s notes or using messaging functions in the electronic health record. A few healthcare workers considered this to be sufficient for establishing a trusting relationship. One primary care provider said “If [a consultant] cc’s me on the chart or sends a message saying ‘This is the plan’, I think that helps a lot.” Despite having the ability to message one another and share notes in the same record system, the majority of healthcare workers thought that communicating through the electronic health record was insufficient. These individuals preferred more in-depth conversations than the electronic health record allowed. Therefore, they used additional means of communication to enrich their collaborations, such as face-to-face conversations.

A shared clinical space facilitated EHR-independent communication for proximal healthcare workers. Opportunities for interaction were ample and included happenstance encounters with other healthcare workers, simultaneous patient visits, phone calls, and group rounds. For example, a podiatrist said: “The hospital is right there. It takes me two minutes. I can go over, do dressing changes, and chat.” EHR-independent forms of communication also facilitated other aspects of working together, and ultimately helped to build trust between healthcare workers.

The components that defined proximity— a shared electronic health record and co-location— facilitated aspects of working together: fulfilling individual responsibilities, timeliness, responsiveness, and not over-stepping professional bounds. Shared electronic health records generally contained features that automated or enhanced communication within a local system. In turn, this enhanced timeliness. One primary care provider described their electronic health record, “All the notes cc back to the [primary care provider] so that they’re aware of what’s going on.” Co-location also provided opportunities to coordinate care. A wound care nurse described:

The physicians over at the clinic here in the hospital will call if they have a patient they’re seeing over in the clinic with a wound or concern. If I have time, I will pop over and see that patient and give recommendations… The convenience of being close is very helpful.

Direct communication facilitated individual healthcare worker accountability and responsiveness, while simultaneously creating less opportunity for over-stepping professional bounds.

A majority of healthcare workers emphasized the importance of time in establishing a solid trusting relationship through iterative cycles of communication and working together. Among proximal healthcare workers, these cycles were reinforced over multiple patients. An infectious disease advanced practice provider explained, “The more we work as a team and the more we work with certain members of a department, the more comfortable we get sharing patients.” Multiple opportunities to share patients over time led to a mutual history, which strengthened trust. Distributed dyads were less likely to share multiple patients over time, resulting in fewer cycles of communication and working together and, ultimately, a weaker sense of trust.

Building Trust with Distributed Healthcare workers

Distributed healthcare workers were less comfortable working together than proximal dyads. One primary care provider juxtaposed working with proximal and distributed professionals:

The docs I work with in my clinic, I know them really well. I feel very comfortable approaching them and saying “Hey, have you seen this before? How would you manage this?” It is a collegial atmosphere… But, sometimes the system outside of my clinic feels big. I haven’t met these specialists face-to-face. There have been times when I’ve messaged another doc and don’t get a response, or I get their note and it didn’t really address what I was hoping to ask.

The components of building trust— introductions, communication, and working together over time— were operationalized differently when healthcare workers lacked co-location, a shared electronic health record, or both. One podiatrist said, “[Trust] is because of the personal relationships that us physicians have developed with each other, not because the system makes it easy to happen.” Building trust took considerable effort and time for distributed dyads.

Introductions were a significant obstacle for distributed healthcare workers. This was best evidenced by the fact that the vast majority of rural study participants were not familiar enough with urban specialists to suggest contacting one during study recruitment. A diabetes educator lamented, “You are asking about trust because we are all working together toward a common goal, but we don’t even see each other. There are people whose names I know, but I have never even met them.”

Successful, distributed healthcare worker dyads overcame barriers to introductions, but this required more effort than those between proximal dyads. For many, a single phone call or video conference provided a sufficient introduction with a distributed healthcare worker. A telemedicine infectious disease physician, seasoned in remote collaboration, said: “I really think that having at least a phone conversation, but ideally having at least one face-to-face meeting really helps to build a sense of trust.” As such, some individuals went out of their way to meet face-to-face and even exchanged personal telephone numbers in the process. A podiatrist recalled:

I met with one of the vascular surgeons for dinner. We talked about how the longer it takes [for referral], the more tissue loss. So, we’ve established a relationship where he’s not on call 24/7 for me, but he will answer a call or a text from me.

Introductions readied healthcare workers for improved communication, especially EHR-independent communication.

Difficulties with EHR-based communications abounded among distributed healthcare workers dyads. Distributed dyads struggled with incompatible electronic health records or subpar interfaces. Healthcare workers who were not introduced to one another often relied upon EHR-based communication, despite recognizing its shortcomings, because they lacked ready access to other modes of communication. Healthcare workers assumed that notes and results successfully reached their distributed counterparts. This was acknowledged by both senders and recipients. A vascular surgeon reported, “Even though I try [to send my note back to the primary care provider], I really don’t know if it actually makes it to them, or how long it takes.” A primary care provider confirmed, “I think [distributed consultants] know that I have access to their [electronic health record]. The onus is on me to find what they’re doing and monitor it, rather than them communicating back to me.”

Healthcare workers who introduced themselves were more likely to use EHR-independent forms of communication. Like proximal dyads, many distributed dyads thought that communication was of higher quality when conducted outside the electronic health record. It helped to build a sense of trust in one another’s clinical acumen. For example, a telemedicine infectious disease physician said: “[Communicating outside the electronic health record] helps get an idea of how the other person approaches problems that you can’t get from reviewing their documentation or notes.” The frequency with which distributed dyads used EHR-independent forms of communication varied widely. Some healthcare workers wanted to communicate via phone or other means for each shared patient. Others wanted EHR-independent forms of communication readily available as a back-up. A primary care provider explained, “When you place a referral, you want to feel like you have a way to get in touch with the specialist and discuss next steps if there’s a difference of opinions.” For others, coordination was presumed to proceed primarily through the electronic health record. A primary care provider remarked on ancillary tools in her electronic health record: “I’ve always appreciated it when I get an in-basket message in addition to the consult note… Just a willingness to keep the conversation going is nice.”

Distributed dyads were more likely to struggle to work together when introductions were not made, and communication was limited. A nurse commented, “When you fax something over to another provider’s office, and you’re just trusting that they’re going to know what to do with it, things are going to slip through the cracks.” As electronic health record interfaces became more compatible, the sense of timeliness and responsiveness increased. For some distributed dyads with easily compatible records, EHR-based communication was sufficient to foster a sense of working together. One primary care provider remarked, “Hopefully we’re getting timely consults back. You send somebody to [a distributed consultant] and you get a note back from them. You don’t have to chase down the notes.” A few distributed dyads who took the initiative to introduce themselves and communicate outside the electronic health record were well prepared to address aspects of working together. A primary care provider described the responsiveness of one of his consultants, “The infectious disease guy, he’s a guy that I call up because he wants to know. He will call back and say ‘Tell me, what’s the story?”’ A vascular surgeon who often telephoned other colleagues emphasized that this type of “good communication [led to] recognizing our boundaries.”

Although rare, distributed dyads who were able to accomplish all three steps— introductions, communication (especially EHR-independent communication), and working together— developed trusting working relationships that spanned multiple patients over time. One primary care provider said:

I know one of the endocrinologists at another clinic. I’ve talked to her on the phone over the years. I don’t know if I could recognize her if she showed up at my door, but I have referred several patients to her…

Like in proximal collaborations, a shared history of patients, and a willingness to re-engage a distributed colleague, affirmed a trusting working relationship.

Patient Outcomes and Feedback

Patients’ clinical outcomes also informed trust and rapport between proximal and distributed healthcare workers. A vascular surgeon explained how healing or improved outcomes impacted healthcare worker relationships: “…[primary care providers] see their patients get better. The patient comes back, and they’re happy with the care. So the [primary care provider] knows that this works.” Improved clinical outcomes could act as a positive feedback loop in referrals, and bolster trust. A diabetic educator explained, “I think when [primary care providers] see the results of other patients, then they’re more motivated to send me new people. Because, they know that I know what I’m doing.”

Patient reactions to consults also informed trust between healthcare workers, regardless of proximity. They provided clinicians with a sense for one another’s interpersonal skills. Healthcare workers preferred to make referrals to individuals who treated their patients with respect, which was recognized by both consultants and referring healthcare workers. One primary care provider said, “Sometimes you send patients to a tertiary care center, and you get feedback when they come back: ‘That was a really good experience’ versus ‘Oh my gosh, I would never go see that person again.’” Specialists also recognized the weight that patient feedback carried. A vascular surgeon said, “The three As of a good surgeon are availability, affability, and ability. You need to be nice to the patient. With the patients reporting back to [primary care providers], I’ve always felt that’s really important.” Among distributed dyads with little communication, patient outcomes and experiences heavily influenced trust between healthcare workers.

Discussion

Although its importance is recognized in improving interprofessional care and patient outcomes, little is known about how trust between healthcare workers is formed. Ours is one of the first studies to describe the process of building this trust, and how it varies based on proximity (Cramton, 2001; Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1999; Priest et al., 2006). We found that trust between healthcare workers is established over time and facilitated by introductions, communication, and working together. Shared successes and good patient rapport were also beneficial. Healthcare workers who were proximal to one another, defined as co-located with a shared electronic health record, more easily built trust compared to their distributed dyads. Although our definition of proximal versus distributed dyads emerged from our data, this concept is well-established in the systems engineering literature (Bell & Kozlowski, 2002; Fiore et al., 2003). Engineering defines distributed professionals as those separated by space and time who rely on technology for communication. Studies of distributed collaborations and teams, typically in global business settings, stress the importance of communication and trust to optimal performance (Cramton, 2001; Driskell et al., 2003; Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1999; Venkatesh & Johnson, 2002). Therefore, this body of literature corroborates our study’s findings among distributed healthcare workers. Our study has important implications for cultivating trust at the level of healthcare worker dyads, interprofessional collaborations and teams, and healthcare systems.

At the level of healthcare worker dyads, our findings overlap with previous work on referral patterns, which directly correlate with healthcare worker trust (Gregory & Austin, 2016). A survey of 553 primary care providers identified: (a) previous experience with the specialist, (b) timeliness, (c) quality communication, and (d) patient rapport as four of the top five considerations when choosing a consultant (Kinchen et al., 2004). These map to our themes of: (a) developing trust over time, (b) timeliness, (c) communication, and (d) patient experiences. Similarly, Choudhry and colleagues (2014) published a list of questions to consider when selecting a specialist, including:

How well will the specialist communicate with the referring physician?

Do both physicians use the same electronic health record?;

Does the specialist communicate well with patients?

These questions confirm the importance of our findings regarding healthcare worker communication, shared electronic health records, and patient experiences.

When considering initiatives to support trust at the level of healthcare workers, our findings suggest that currently practicing professionals invest in making introductions and at least one EHR-independent communication. This may be particularly useful for distributed healthcare workers. Additionally, those in training may benefit from formal education on these topics (Brock et al., 2013; DeChurch et al., 2011; Supper et al., 2015; Sy, 2017).

At the level of interprofessional healthcare collaborations and teams, we found that trusting relationships took time to develop. This was also emphasized in studies of physicians and nurses working together in an emergency department, interprofessional cancer teams, nurse-resident physician collaboration in the intensive care setting, and primary care provider-cardiologist collaboration (Baggs & Schmitt, 1997; Davidow et al., 2018; Friberg et al., 2016; Soukup et al., 2018). Primary care providers participating in a qualitative study about their collaborations with pharmacists stressed that trust among team members was earned over time, not conferred due to a title or degree (Gregory & Austin, 2016). Based on our findings, and those available in the literature, we suggest that interprofessional collaborations and teams strive for consistent members over time as a means of enhancing trust between healthcare workers. If an interprofessional team, rather than collaboration, is required, involving as many proximal team members as possible may be desirable due to the necessity of working together with a high degree of trust, integration, and interdependence.

At the level of healthcare systems, we found that co-location and shared electronic health records were critical supports to building trusting relationship between healthcare workers. Three studies affirmed that shared clinic space with opportunities for face-to-face interactions facilitate interprofessional care (Baggs & Schmitt, 1997; Davidow et al., 2018; Szafran et al., 2018). When planning space utilization within a healthcare system, efforts to co-locate different professions are likely to support interprofessional trust. The importance of easily exchanged information within and across electronic health records is clear, although not currently realized. Approximately half of U.S.-based physicians reported they are unable to share clinical summaries, laboratory/diagnostic test results, and patient medication lists outside of their practice (Davidow et al., 2018; Doty et al., 2020). Furthermore, only one in three primary care providers reported that they typically received reports within one week of a patient’s consultation with a specialist (Davidow et al., 2018; DeChurch et al., 2011). This erodes healthcare workers’ trust in one another. We suggest healthcare systems and policies invest in enhancing the compatibility of electronic health records across organizations as a means to support trust between healthcare workers and improve patient outcomes.

Like all studies, ours has limitations. First, all participants were recruited from healthcare systems in the Midwestern United States. Healthcare workers working in universal healthcare systems or in areas with different infrastructure may have different experiences. Second, we did not explicitly ask about power structures and the impact of hierarchy among interprofessional dyads. This is likely to influence how trust develops, but we did not probe for it, and the vast majority of our participants did not raise the issue. Third, we did not formally assess whether proximal and distributed dyads were engaged in collaboration versus teamwork to provide interprofessional care. However, our existing data led us to hypothesize that proximity influences the ability to move from collaboration to more cohesive teamwork. Fourth, we did not fully explore whether distributed dyads who lacked both criteria for proximity (co-location and a shared electronic health record) struggled more to build trust compared with distributed dyads who lacked a single criteria. However, our results suggest this may be the case. As electronic health records became increasingly compatible, healthcare workers reported a stronger sense of timeliness and responsiveness, attributes that promote trust. We encourage further research to test this emerging hypothesis. Fifth, participants were informed that they would be compensated $100 prior to completing the interview. This may have led to socially desirable responses, but our intention at the time of the interviews was not to focus on trust between healthcare workers. Rather, its importance was emphasized by participants and suggests responder bias minimally affected our results. Lastly, our sample was limited to healthcare workers involved in diabetic foot ulcer care, which was the medical focus of our inquiry. However, based on the correlation of our findings with existing studies outside this context, our results are likely to resonate across interprofessional teams caring for patients with different medical conditions. Future studies are needed to examine the potential impact of these differences on trust between healthcare workers.

Conclusion

Our study provides an in-depth description of how trust is built between healthcare workers on interprofessional teams caring for patients with diabetic foot ulcers. It emphasizes the importance of introductions, communication, working together, and patient outcomes and experiences. Building trust is easier for proximal dyads, or those who are co-located and share an electronic health record, compared to distributed providers. Our results suggest how individual healthcare workers, interprofessional teams, and health systems can help support trust, which should enhance team performance, and patient outcomes. Further research is needed to engineer teams and broader systems that support trusting relationships, especially across distributed settings where healthcare workers struggle the most to build and maintain these critical connections.

Acknowledgements

We thank David Hahn and the Wisconsin Research & Education Network for their help in purposively recruiting rural primary care providers. We appreciate the transcriptional services of Christie Schlabach, Matthew Swenson, Alexis Boram, Lilly Nguyen, and Jillian Incha. We thank Cheryl DeVault and the Rural Wisconsin Health Cooperative Primary Care Roundtable participants for their assistance with determining transferability of our emerging results. Lastly, we wish to acknowledge the help of Nora Jacobson and the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research Qualitative Research Group members, who provided methodologic insights and safeguarded the confirmability of our results.

Funding details

This work was supported by the Wisconsin Partnership Program under grant WPP 3086 pilot, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) under grant 1K08HS026279. Additional support was through the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) under grant UL1TR002373. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the AHRQ or NIH. Funding agencies did not participate in decisions regarding: study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation, or publication.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

None of the authors have relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to disclose.

References

- Baggs JG, & Schmitt MH (1997). Nurses’ and resident physicians’ perceptions of the process of collaboration in an MICU. Research in Nursing & Health, 20(1), 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett ML, Song Z, & Landon BE (2012). Trends in physician referrals in the United States, 1999-2009. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(2), 163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels CM, Roberts TJ, Hansen KE, Jacobs EA, Gilmore A, Maxcy C, & Bowers BJ (2016). Rheumatologist and primary care management of cardiovascular disease risk in rheumatoid arthritis: Patient and provider perspectives. Arthritis Care & Research, 68(4), 415–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell BS, & Kozlowski SWJ (2002). A typology of virtual teams: Implications for effective leadership. Group & Organization Management, 27(1), 14–49. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan MB, Barocas JA, Crnich CJ, Hess TM, Kolehmainen CJ, Sosman JM, & Sethi AK (2015). “Oops! I forgot HIV”: Resident physician self-audits and universal HIV screening. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 8(2), 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock D, Abu-Rish E, Chiu CR, Hammer D, Wilson S, Vorvick L, Blondon K, Schaad D, Liner D, & Zierler B (2013). Interprofessional education in team communication: Working together to improve patient safety. BMJ Quality & Safety, 22(5), 414–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2021). Chronic conditions data warehouse: Conditions categories. https://www2.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories

- Choudhry NK, Liao JM, & Detsky AS (2014). Selecting a specialist: Adding evidence to the clinical practice of making referrals. The Journal of the American Medical Aassociation, 312(18), 1861–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramton CD (2001). The mutual knowledge problem and its consequences for dispersed collaboration. Organization Science, 12(3), 346–371. [Google Scholar]

- Davidow SL, Sheth J, Sixta CS, & Thomas-Hemak L (2018). Closing the referral loop: Improving ambulatory referral management, electronic health record connectivity, and care coordination processes. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 41(4), 240–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeChurch LA, Burke CS, Shuffler ML, Lyons R, Doty D, & Salas E (2011). A historiometric analysis of leadership in mission critical multiteam environments. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(1), 152–169. [Google Scholar]

- Doty MM, Tikkanen R, Shah A, & Schneider EC (2020). Primary care physicians’ role in coordinating medical and health-related social needs in eleven countries. Health Affairs, 39(1), 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driskell JE, Radtke PH, & Salas E (2003). Virtual teams: Effects of technological mediation on team performance. Group Dynamics-Theory Research and Practice, 7(4), 297–323. [Google Scholar]

- Elo S, & Kyngas H (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore SM, Salas E, Cuevas HM, & Bowers CA (2003). Distributed coordination space: Toward a theory of distributed team performance. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomic Science, 4(3-4), 340–364. [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Mauksch L, Bodenheimer T, & Salas E (2017). Improving care teams’ functioning: Recommendations from team science. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 43(7), 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel RM, Tilden VP, & Suchman A (2019). Physicians’ trust in one another. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 321(14), 1345–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friberg K, Husebo SE, Olsen OE, & Saetre Hansen B (2016). Interprofessional trust in emergency department - As experienced by nurses in charge and doctors on call. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(21-22), 3252–3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory PA, & Austin Z (2016). Trust in interprofessional collaboration: Perspectives of pharmacists and physicians. Canadian Pharmacists Journal, 149(4), 236–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guba EG, & Lincoln YS (1982). Epistemological and methodological bases of naturalistic inquiry. Educational Technology Research and Development, 30, 233–252. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvenpaa SL, & Leidner DE (1999). Communication and trust in global virtual teams. Organization Science, 10(6), 791–815. [Google Scholar]

- Kinchen KS, Cooper LA, Levine D, Wang NY, & Powe NR (2004). Referral of patients to specialists: Factors affecting choice of specialist by primary care physicians. Annals of Family Medicine, 2(3), 245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolehmainen C, Brennan M, Filut A, Isaac C, & Carnes M (2014). Afraid of being “witchy with a ‘b”’: A qualitative study of how gender influences residents’ experiences leading cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical College, 89(9), 1276–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, & Guba EG (1985). Naturalist inquiry. SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch T (2018). Background paper (Document No. ABIMF2018). American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. https://abimfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/2018-ABIM-Foundation-Forum-Background-Paper.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM (2000). Determining sample size. Qualitative Health Research, 10(1), 3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musuuza J, Sutherland BL, Kurter S, Balasubramanian P, Bartels CM, & Brennan MB (2020). A systematic review of multidisciplinary teams to reduce major amputations for patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 71(4), 1433–1446.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes K, Monson JR, Rizvi I, Savastano A, Green JS, & Sevdalis N (2016). Regional multiteam systems in cancer care delivery. Journal of Oncology Practice, 12(11), 1059–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, & Beck CT (2012). Sampling in qualitative research. In Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (pp. 515–531). Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippencott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Priest HA, Stagl KC, Klein C, & Salas E (2006). Virtual teams: Creating context for distributed teamwork. In Creating high-tech teams: Practical guidance on work performance and technology (pp. 185–212). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Soukup T, Lamb BW, Arora S, Darzi A, Sevdalis N, & Green JS (2018). Successful strategies in implementing a multidisciplinary team working in the care of patients with cancer: An overview and synthesis of the available literature. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 11, 49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supper I, Catala O, Lustman M, Chemla C, Bourgueil Y, & Letrilliart L (2015). Interprofessional collaboration in primary health care: A review of facilitators and barriers perceived by involved actors. Journal of Public Health, 37(4), 716–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland BL, Pecanac K, Bartels CM, & Brennan MB (2020). Expect delays: Poor connections between rural and urban health systems challenge multidisciplinary care for rural Americans with diabetic foot ulcers. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research, 13(1), 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sy MP (2017). Filipino therapists’ experiences and attitudes of interprofessional education and collaboration: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 31(6), 761–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szafran O, Torti JMI, Kennett SL, & Bell NR (2018). Family physicians’ perspectives on interprofessional teamwork: Findings from a qualitative study. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32(2), 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh V, & Johnson P (2002). Telecommuting technology implementations: A within- and between-subjects longitudinal field study. Personnel Psychology, 55(3), 661–687. [Google Scholar]