Abstract

Evidence indicates that carbon dioxide (CO2) induces negative affective states (including anxiety, fear and distress) in laboratory rodents, but many countries still accept it for euthanasia. Alternative methods (e.g. inhalant anaesthetic) may represent a refinement over CO2 but are not widely adopted. We conducted an online survey of Canadian and European laboratory animal professionals and researchers (n = 592) to assess their attitudes towards the use of CO2 and alternative methods for rodent euthanasia using quantitative 7-point scale (from 1 (= strongly oppose) to 7 (= strongly favour) and qualitative (open-ended text) responses. CO2 was identified as the most common method used to kill rodents, and attitudes towards this method were variable and on average ambivalent (mean ± SD score on our 7-point scale was 4.4 ± 1.46). Qualitative analysis revealed four themes relating to participant attitude: (a) the animal’s experience during gas exposure; (b) practical considerations for humans; (c) compromise between the animal’s experience and practical considerations; and (d) technical description of the procedure or policies. Many participants (51%) felt that there were alternatives available that could be considered an improvement over CO2, but perceived barriers to implementing these refinements. Qualitative analysis of these responses revealed five themes: (a) financial constraints; (b) institutional culture; (c) regulatory constraints; (d) research constraints; and (e) safety concerns. In conclusion, concerns regarding the use of CO2 often focused on the animal’s experience, but barriers to alternatives related to operational limitations. New research is now required on to how best to overcome these barriers.

Keywords: Mixed methods, animal welfare, humane killing

Attitudes des professionnels des animaux de laboratoire et des chercheurs à l’égard de l’euthanasie des rongeurs au dioxyde de carbone et obstacles au changement perçus Résumé

Les données indiquent que le dioxyde de carbone (CO2) induit des états affectifs négatifs (dont l'anxiété, la peur et la détresse) chez les rongeurs de laboratoire, mais de nombreux pays l'acceptent encore pour l'euthanasie. D'autres méthodes (par exemple, l'anesthésique inhalé) peuvent représenter un raffinement par rapport au CO2, mais ne sont pas largement adoptées. Nous avons mené une enquête en ligne auprès de professionnels et de chercheurs de laboratoires canadiens et européens (n= 592) afin d’évaluer leurs attitudes à l’égard de l’utilisation du CO2 et des méthodes alternatives pour l’euthanasie des rongeurs à l’aide d’2 et des méthodes alternatives pour l’euthanasie des rongeurs à l’aide d’une échelle quantitative de 7 points (de 1 = fortement opposé à 7 = fortement en faveur) et qualitative (texte ouvert) réponses. LE CO2 a été identifié comme la méthode d’euthanasie des rongeurs la plus courante, et les attitudes à l’égard de cette méthode étaient variables et en moyenne ambivalentes (le score moyen ± ET sur notre échelle de 7 points était de 4,4 ± 1,46). L'analyse qualitative a révélé quatre thèmes liés à l'attitude des participants: 1) l’expérience de l’animal pendant l’exposition au gaz, 2) les considérations pratiques pour les humains, 3) le compromis entre l’expérience de l’animal et les considérations pratiques et 4) la description technique de la procédure ou des politiques. De nombreux participants (51%) estimaient qu’il existait des solutions de rechange qui pourraient être considérées comme une amélioration par rapport au CO2, mais ils pensaient qu’il existait également des obstacles à la mise en œuvre de ces raffinements. L'analyse qualitative de ces réponses a révélé cinq thèmes: 1) les contraintes financières, 2) la culture institutionnelle, 3) les contraintes réglementaires 4) les contraintes de recherche et 5) les préoccupations en matière de sécurité. En conclusion, les préoccupations concernant l’utilisation du CO2 ont souvent porté sur l’expérience de l’animal, mais les obstacles aux alternatives étaient liées aux imitations opérationnelles. De nouvelles recherches sont maintenant nécessaires sur la meilleure façon de surmonter ces obstacles.

Einstellungen und Ansichten von Versuchstierkundlern und -forschern bezüglich des Einsatzes von Kohlendioxid zur Tötung von Nagern und bezüglich der Hindernisse für Veränderungen Abstract

Obgleich es erwiesen ist, dass Kohlendioxid (CO2) bei Labornagern negative affektive Zustände (darunter Unruhe, Angst und Stress) hervorruft, gilt es in vielen Ländern jedoch nach wie vor als akzeptiertes Mittel zur Tötung. Alternative Methoden wie z. B. Inhalationsanästhesie, die im Vergleich zu CO2 eine Verbesserung darstellen, werden selten angewendet. Wir haben eine Online-Umfrage unter kanadischen und europäischen Versuchstierkundlern und -forschern (n=592) durchgeführt, um ihre Einstellung zur Verwendung von CO2 und zu alternativen Methoden zur Tötung von Nagetieren anhand einer quantitativen 7-Punkte-Skala (von 1= stark ablehnend bis 7 = stark befürwortend) und qualitativer Antworten (offener Text) zu bewerten. CO2 wurde als die am häufigsten verwendete Methode zur Tötung von Nagern identifiziert. Die Ansichten zu dieser Methode waren unterschiedlich und im Durchschnitt unentschieden (mittlerer ± SD-Wert auf unserer 7-Punkte-Skala war 4,4 ± 1,46). Die qualitative Analyse ergab vier Aspekte in Bezug auf die Einstellung der Teilnehmer: 1) Reaktionen/Erfahrungen des Tieres während der Gasexposition, 2) praktische Überlegungen für den Menschen, 3) Kompromiss zwischen den Reaktionen/Erfahrungen des Tieres und praktischen Überlegungen und 4) technische Beschreibung des Verfahrens oder der Richtlinien. Viele Teilnehmer (51%) waren der Meinung, dass es Alternativen gibt, die als Verbesserung gegenüber CO2 angesehen werden könnten, sahen aber Hindernisse bei der Umsetzung dieser Verbesserungen. Die qualitative Analyse dieser Antworten ergab fünf Aspekte: 1) finanzielle Zwänge, 2) institutionelle Kultur, 3) regulatorische Auflagen, 4) Forschungseinschränkungen und 5) Sicherheitsbedenken. Zusammenfassend lässt sich sagen, dass Bedenken bezüglich der Verwendung von CO2 häufig Bezug auf die Erfahrungen des Tieres nahmen, die Hemmnisse für Alternativen jedoch mit praktischen Beschränkungen zusammenhingen. Daher bedarf es weiterer Forschungsarbeit, um zu ermitteln, wie diese Hemmnisse am besten überwunden werden können.

Actitud de los profesionales e investigadores que utilizan animales de laboratorio respecto a la eutanasia por inhalación de dióxido de carbono para roedores y obstáculos que deben superarse Resumen

Las pruebas demuestran que el dióxido de carbono (CO2) provoca estados emocionales negativos (como ansiedad, miedo y estrés) en roedores de laboratorio pero muchos países siguen utilizando este método para la eutanasia. Métodos alternativos (p. ej., anestesia por inhalación) pueden representar un refinamiento respecto al CO2 pero es una técnica todavía no generalizada. Hemos realizado una encuesta online de investigadores y profesionales canadienses y europeos que utilizan animales de laboratorio (n=592) para evaluar su actitud respecto al uso de CO2 y métodos alternativos para la eutanasia de roedores utilizando respuestas cuantitativas con una escala de 7 puntos (1= totalmente en contra, 7 = totalmente a favor) y respuestas cualitativas (texto abierto). Se identificó al CO2 como el método más utilizado para sacrificar roedores, y la actitud respecto a este método fue variable y ambivalente en general (la puntuación media ± de desviación estándar de nuestra escala de 7 puntos era de 4,4 ± 1,46). Los análisis cualitativos expusieron cuatro puntos relacionados con la actitud de los participantes: 1) la experiencia del animal durante la exposición al gas, 2) consideraciones prácticas para humanos, 3) compromiso entre la experiencia del animal y las consideraciones prácticas y 4) descripción técnica del procedimiento o las políticas. Muchos participantes (51%) pensaban que había alternativas disponibles que podrían considerarse como una mejora de la técnica con CO2 pero percibieron obstáculos para implementar estos refinamientos. Los análisis cualitativos de estas respuestas expusieron cinco puntos: 1) problemas financieros, 2) cultura institucional, 3) limitaciones en la regulación, 4) limitaciones en la investigación y 5) aspectos de seguridad. En conclusión, existen preocupaciones sobre el uso de CO2 que suelen centrarse en la experiencia del animal, pero hay obstáculos a la hora de implementar estas alternativas debido a las limitaciones operativas. Ahora es necesario realizar más estudios de investigación sobre cómo superar estos obstáculos.

Introduction

Mice and rats are widely used in research; in 2017 nearly 7 million of these animals were used in the member states of The European Union 1 and 1.5 million were used in Canada. 2 Most of these animals were likely killed at the end of the study. It is generally agreed that laboratory animals should be killed humanely – pain, distress, fear and anxiety should be minimal or absent during the killing processes. In addition to considerations regarding the animal’s experience, preferred killing methods should have high reliability, non-reversibility, be compatible with research objectives and safe for the people performing the procedure.3–6 Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the most commonly used method to kill rats and mice; in an international meeting on laboratory animal euthanasia held on 2016, many participants reported using CO2 to kill rodents. 7 This method is conditionally acceptable in Canada 3 and the USA, 5 and is listed as ‘appropriate’ in the Directive 2010/63/EU on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes for the member states of The European Union. 4

After more than 30 years of research assessing the humaneness of CO2 for rodent euthanasia (e.g. Blackshaw et al. 8 and Britt 9 ), its use remains controversial. For example, two recently published literature reviews arrived at contrasting conclusions; Turner and colleagues concluded that there was not enough evidence to determine whether CO2 killing compromises rodent welfare, 10 while Améndola and Weary concluded that CO2 inhalation induces negative emotions in rats likely corresponding to fear, anxiety, dyspnea, distress, and panic. 11 Conflict also surrounds alternative methods such as inhalant anaesthetics, with some scholars arguing that that use of CO2 should continue, 12 and others concluding that alternative methods are more humane.13–15

The lack of consensus from the research community regarding the humaneness of CO2 and viability of alternatives could explain why CO2 continues to be widely used. Implementing even well-accepted refinements to long standing practices within laboratory animal science can be a challenge. For example, more than a decade ago tunnel handling was shown to be better than tail handling as a method of physical capture for mice, reducing both aversion and anxiety induced by restraint, 16 but tail handling of laboratory mice remains common. 17 Additionally, animal caretakers believe the tickling of laboratory rats may benefit their welfare but implementation of the practice is low. 18 These examples suggest that animal users in laboratories face barriers to the adoption of refinements.

The objectives of the current study were to describe (a) the attitudes of laboratory animal professionals and researchers towards CO2 euthanasia of rodents, and (b) the perceived barriers to implementing refinements.

Material and methods

Participants and recruitment

This study was approved by the University of British Columbia’s Behavioural Research Ethics Board (H19-00839). During survey development purposive theory-based sampling was employed to generate participant recruitment strategies. 19 European and Canadian participants were targeted for recruitment because the authors had contacts within the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations, the Canadian Association for Laboratory Animal Science and the Canadian Association for Laboratory Animal Medicine. Through these contacts the survey was distributed to the respective individual members made up primarily of animal care takers, technicians, managers, veterinarians and researchers. Fifteen test participants from the University of British Columbia assessed the survey for errors and clarity. These responses were removed before launching the survey which was then active from 8 April to 22 May 2019.

Survey participants were asked about their attitudes toward the use of CO2 to euthanize rodents. They were asked to indicate their response, using a 7-point scale, to three similarly worded statements:

The use of CO2 to euthanize rodents is: 1, a very bad thing, 4, neither good nor bad, and 7, a very good thing.

The use of CO2 to euthanize rodents is: 1, totally appropriate, 4, neither appropriate nor inappropriate, and 7, totally inappropriate.

The use of CO2 to euthanize rodents is: 1, completely unacceptable, 4, neither acceptable nor unacceptable, and 7, completely acceptable.

In each case intermediate response options (i.e. 2, 3, 5 and 6) were indicated but not labelled. Note that for the second statement the Likert options were reversed (as a type of attention check). We excluded people who gave the same value to all three questions (e.g. 7, 7, 7), except for intermediate values (i.e. 3, 4 or 5) as in this case a consistent response could still be reasonable.

Participants were also asked about the methods they use to euthanize laboratory rodents, about perceived alternative methods, and about barriers to adopting these refinements. Qualitative responses used text boxes to record open-ended explanations of the participant’s views. Participants were also asked a series of demographic questions associated with attitudes towards animals.

We received 657 total responses. After excluding participants that failed the attention check, did not provide qualitative answers, or did not reside inside the European Union or Canada the total number of participants was 592.

Quantitative analysis

Quantitative analyses were carried out with R (R Development Core Team, Version 3.4.1) and RStudio (RStudio, Inc., Version 1.0.136). We assessed internal consistency between the three 7-point scale statements and found high internal consistency across responses (Cronbach alpha = 0.89), so we used the mean of the three values (after reversing responses to the second question) to generate an attitude score. Lower scores reflected unfavourable views, and higher scores more favourable views. Using analysis of variance, we assessed the effects of the use of CO2 as primary method (yes v. no) and of participant demographics, including gender (female v. other), age (continuous in years), level of education (high school v. college/university v. graduate/professional), primary role (animal caretaker v. technician v. management v. veterinarian v. researcher v. other), sector (academic v. pharma/CRO/private v. government v. hospital/clinic v. non-profit v. other) and region (Europe v. Canada). Significant effects of factors with more than two levels were further explored using Tukey post-hoc tests. Normality of the residuals was visually assessed. Results below are reported as mean ± standard error.

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative data were analysed by qualitative description. 20 The authors coded a sample of participant responses from both European and Canadian participants. Codes emerged through constant comparison and axial coding and were consolidated into themes. 21 Inter-coder reliability and codebook validity was established by one author (MB) and another researcher who independently coded a subset of data (following Guest et al. 22 ). Substantial agreement was reached between the two researchers (kappa = 0.75) and consensus was reached on all remaining coded differences. Illustrative quotations were selected based on how effectively these related to the theme; participants associated with the quotes are identified in the text below using an anonymous number assigned upon entry to the survey. When quotations required editing for clarity this is indicated using square brackets around inserted words.

Results

Quantitative analysis

A summary of the demographic data is provided in Table 1. Of the 592 responses, 35% were from Canada and 65% from the European Union. Most responses from the European Union came from the UK (30%), Switzerland (18%), Germany (17%), Spain (7%) and France (7%). Most participants self-identified as female (67%), from the academic sector (65%) and holding a post-graduate degree (60%). Many participants reported using CO2 as their primary method to euthanize laboratory rodents (47%; Table 2). Additionally, most participants stated there are (52%) or may be (37%) methods which they considered improvements over CO2; only 12% felt that there were no such refinements available.

Table 1.

Demographics of survey participants (n = 592).

| Demographics | n | % | Attitude score (mean ± SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–29 | 57 | 9.6 | 4.21 ± 0.19 |

| 30–39 | 175 | 29.6 | 4.18 ± 0.1 | |

| 40–49 | 174 | 29.4 | 4.56 ± 0.11 | |

| 50+ | 186 | 31.4 | 4.38 ± 0.11 | |

| Gender | Female | 398 | 67.2 | 4.26 ± 0.07 |

| Male | 188 | 31.8 | 4.51 ± 0.11 | |

| Non-binary | 6 | 1 | 5.94 ± 0.47 | |

| Education | High school | 28 | 4.7 | 4.86 ± 0.25 |

| College or university | 212 | 35.8 | 4.22 ± 0.1 | |

| Masters, doctorate, DVM, MD | 352 | 59.5 | 4.4 ± 0.08 | |

| Role | Animal caretaker | 24 | 4 | 4.58 ± 0.26 |

| Technician | 128 | 21.6 | 4.2 ± 0.13 | |

| Management | 114 | 19.3 | 4.43 ± 0.13 | |

| Veterinarian | 172 | 29.1 | 4.32 ± 0.14 | |

| Researcher | 121 | 20.4 | 4.45 ± 0.14 | |

| Other | 33 | 5.6 | 4.36 ± 0.29 | |

| Sector | Academic | 387 | 65.4 | 4.41 ± 0.08 |

| Pharma, CRO, private | 105 | 17.7 | 4.3 ± 0.13 | |

| Government | 36 | 6.1 | 3.82 ± 0.27 | |

| Hospital/clinic | 29 | 4.9 | 4.31 ± 0.19 | |

| Non-profit | 21 | 3.5 | 4.38 ± 0.29 | |

| Other | 14 | 2.4 | 4.83 ± 0.39 | |

| Country | Canada | 209 | 35.3 | 4.21 ± 0.1 |

| Europe | 383 | 64.7 | 4.44 ± 0.1 | |

Table 2.

Primary method of rodent euthanasia reported from survey of European and Canadian laboratory animal professionals and researchers (n = 592).

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| CO2 | 277 | 46.8 |

| Cervical dislocation | 138 | 23.3 |

| Isoflurane | 48 | 8.1 |

| Decapitation | 26 | 4.4 |

| Pentobarbital | 20 | 3.4 |

| Concussion | 13 | 2.2 |

| Other | 27 | 4.6 |

| Don't know | 43 | 7.2 |

| Total | 592 |

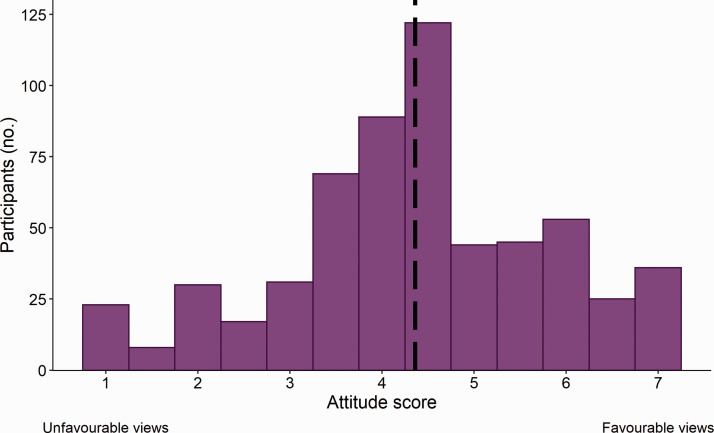

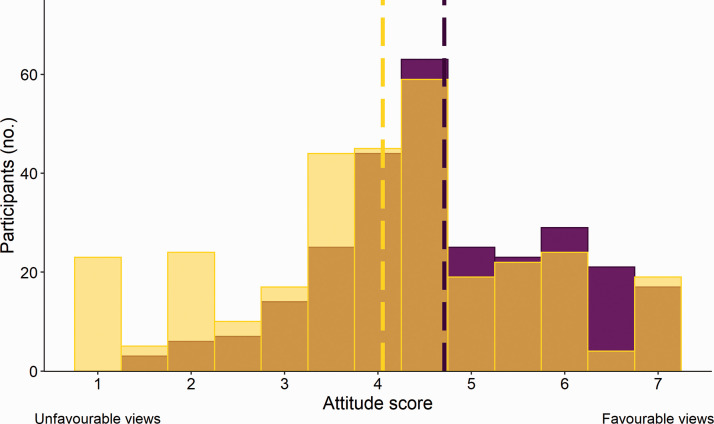

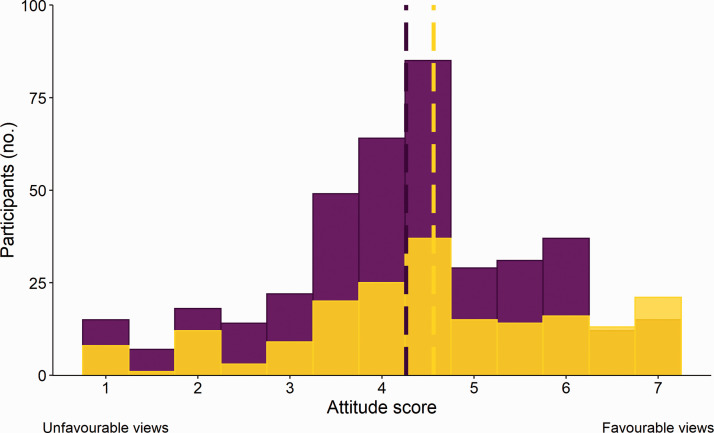

The mean attitude score ranged between 1 and 7, and averaged 4.4 ± 0.06 reflecting an ambivalent attitude to CO2 euthanasia (Figure 1). Participants who reported using CO2 as their primary method showed more support for its use than those who reported using other methods (F1, 575 = 30.81, p < 0.0001; Figure 2). Female participants were slightly less supportive (F1, 575 = 5.13, p = 0.02; Figure 3) which is consistent with other studies reporting gender differences in attitudes towards animals.23–25 We found no effect of age (F1, 575 = 2.41, p = 0.12), education (F2, 575 =2.01, p = 0.13), role (F5, 575 = 0.29, p = 0.92), sector (F 5, 575 = 1.46, p = 0.20), or region (F1, 575 = 1.09, p = 0.30).

Figure 1.

Attitude score towards the procedure of CO2 euthanasia of rodents from European and Canadian (n = 592) laboratory animal professionals and researchers.

Figure 2.

Attitude score towards the procedure of CO2 euthanasia of rodents from laboratory animal professionals and researchers that use CO2 as their primary method (purple) and that use other methods (yellow) (n = 592).

Figure 3.

Attitude score towards the procedure of CO2 euthanasia of rodents from female (purple) and others (yellow) (n = 592) laboratory animal professionals and researchers.

Qualitative analysis

Four themes emerged from the qualitative analysis of participant responses related to CO2 euthanasia: (a) the animal’s experience during gas exposure, (b) practical considerations for humans that used this procedure, (c) compromise between the animal’s experience and practical considerations, and (d) technical description of procedure or policies (Table 3). The majority of participants (58%) framed their response in the context of the animal’s experience. Participants framed these answers as either providing a good death (e.g. ‘If done properly it is a humane method of euthanasia’, participant 762) or a poor one (e.g. ‘I feel CO2 is extremely stressful and painful to the animal’, 927). One quarter of participants (25%) discussed practical considerations. For example, one participant (930) stated ‘A quick and safe method…’, and another respondent (480) noted that CO2 is ‘Good for [euthanizing] large [numbers] of rodents’. The practicality (e.g. ‘It’s fast, effective, and requires minimal training’, 259) and ease (e.g. ‘uncomplicated method of euthanasia’, 41) of training was also noted by participants. Some participants (12%) indicated reservations about CO2 euthanasia and that they saw compromise between the practical considerations and the animal’s experience. For example, participant 86 stated: ‘I believe that CO2 euthanasia is associated with poor welfare; however, until more practical solutions for rodent euthanasia are available, [it] may be our best available practical option.’ Finally, 11% of participants did not specifically offer an opinion on the procedure but instead provided a technical description. For example, participant 113 stated ‘We still have no replacement method…’. Others described national or institutional regulations, for example, ‘Carbon dioxide euthanasia is a Schedule 1 method in the UK and as such is permitted’ (87).

Table 3.

Themes present in attitudes towards CO2 euthanasia of rodents from European and Canadian laboratory animal professionals and researchers (n = 592).

| Themes | n a | % |

|---|---|---|

| Animal experience | 341 | 57.6 |

| Practical considerations | 150 | 25.3 |

| Compromise | 69 | 11.6 |

| Technical description | 63 | 10.6 |

aMore than one theme can be present in each response.

Qualitative analysis of perceived barriers to adopting refinements identified five themes: (a) financial constraints, (b) institutional culture, (c) regulatory constraints, (d) research constraints, and (e) safety concerns (Table 4). The majority of participants (67%) described financial constraints including a lack of money, equipment, or time as a barrier to adopting refinements for rodent euthanasia. For example, participant 404 mentioned that ‘Monetary constraints [and] infrastructure may not be suitable’ and identified the ‘need for [a] professionally trained operator to apply method correctly’. The institutional culture was described as a barrier in 16.8% of responses; participants stated, for example, that ‘We’ve always done it that way’ (24), ‘Resistance to change’ (58), and ‘People are the main barriers…’ (42). Other responses (12%) referred to legal, regulatory and institutional policy as barriers to adopting refinements. Participant 156 identified Canada’s ‘Controlled substance legislation’, and participant 54 mentioned the UK’s ‘Personal licence restrictions’ as barriers. Some participants (11%) described research constraints, for example, stating that alternatives may disrupt scientific outcomes: ‘Injectables may effect more organs than CO2 and may interfere with study results’ (76). Finally, human or animal safety concerns were described as barriers in 10% of responses. For example, participant 205 wrote that ‘Waste [isoflurane] gas is hazardous to humans’.

Table 4.

Themes present in the perceptions of barriers to the implementation of refinements for CO2 euthanasia of rodents from European and Canadian laboratory animal professionals and researchers (n = 297).

| Themes | n a | % |

|---|---|---|

| Financial constraints | 198 | 66.7 |

| Institutional culture | 50 | 16.8 |

| Regulatory constraints | 35 | 11.8 |

| Research constraints | 34 | 11.4 |

| Safety concerns | 31 | 10.4 |

aMore than one theme can be present in each response.

Discussion

We found that CO2 continues to be a commonly used method of killing laboratory rodents, with nearly 50% of European and Canadian participants stating that this method was used most often in their facilities. Most participants had intermediate attitude scores (60% scored between 3 and 5), but those who reported using CO2 as their primarily methods were slightly more supportive. However, even among CO2 users, only 33% had favourable views (i.e. scored above 5) towards the use of CO2 to euthanize laboratory rodents. When asked to describe the reasons for their attitude, many participants referred to the perceived experiences of the animals. Participants varied in their interpretation of the animals’ experiences, with some believing that CO2 exposure was a significant source of suffering and other disagreeing. Thus, it is reasonable to infer that many participants who use CO2 as a primary euthanasia method are not convinced that this method provides a good death. These results are consistent with the ongoing debate within the scientific community where some authors argue that CO2 euthanasia causes suffering in rodents 11 and others argue there is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions regarding the method. 10 The current study did not assess if the information used by participants to interpret the animals’ experiences came from their knowledge of the scientific literature, personal experience, or information provided by regulatory bodies. Future studies should consider what and how information is used by laboratory animal professionals to inform their views.

Some participants explained their attitude towards CO2 killing in relation to practicality of the method and others weighed the animal experiences against practical considerations. These participants seemed to value the animal’s experience but often prioritized the practicality of training or existing availability. Previous research has shown a bias towards practicality when participants are faced with uncertainty, 26 efforts to increase consensus among professionals may attenuate participant uncertainty and bias.

We are unsure of how to interpret responses from participants who simply offered technical descriptions when justifying their attitudes. This might reflect a lack of understanding of our questions, or perhaps more substantially an uneasiness with introspection on this topic. Research has shown that survey participants often use little cognitive effort in their responses and instead rely on heuristics; 27 it is easier to substitute the substantive question (‘what should I do’) with the more simple question (‘what am I allowed to do’) when asked to justify morally relevant actions. Other methodologies that allow for probing of participant responses may provide a better understanding of the views of these participants.

Many participants believed that refined killing procedures exist, but barriers prevented their implementation. Interestingly, perceived financial constraints were identified by two-thirds of participants, and another 10% identified regulatory constraints as a barrier to adopting these refinements. This result is of special interest as both Canadian 28 and European Union 4 regulations specifically require committees approving animal use to implement welfare refinements. Institutions that conduct animal research may be reluctant to financially support refinements when the implementation of current practices meets regulatory obligations. Our study highlights the need for additional research to specifically explore the role financial resources plays in the implementation of animal welfare refinements.

Interference with research paradigms, animal or human safety concerns, and the culture within institutions were all identified by participants as barriers to change. In some cases, refined rodent euthanasia procedures that compromise research data or endanger the health and wellbeing of humans or animals cannot be implemented. However, in these cases efforts should continue to investigate risk mitigation strategies to enable deployment of refinements. Similar to previous research, the current study has identified organizational reasons for resistance to change. 29 Future research should specifically focus on the cultural aspects of laboratory environments that create barriers to change.

A lack of scientific evidence did not emerge as a theme in responses regarding barriers to adopting refinements; this result suggests that new scientific research addressing the humaneness of CO2 killing is unlikely to help laboratory animal professionals. Interestingly, participants in a recent survey that explored the implementation of handling techniques in laboratory mice did identify a lack of scientific research as a barrier. 17 It is possible that more in depth qualitative research methods would identify specific gaps in the science that require new research in euthanasia, but the results of the current study suggest that the focus for new research should be on understanding and addressing barriers to adopting refinements.

The current survey had several limitations. We recruited participants through email distribution; we recognize the potential for sampling bias, as participants with a particular interest in the topic might have been more willing to participate in the survey. In this case we might have expected to see many responses who were either strongly supportive or strongly opposed to the method. In contrast, we found that most participants were ambivalent, and their detailed qualitative responses indicated that they often held nuanced views understanding both the welfare impact of the procedure and practical constraints. Our participants were predominantly older, female, educated and working in an academic environment; we did not have access to the demographic breakdown of the populations from which we recruited. We encourage future studies to obtain a better estimate of population characteristics (for example, using the records for the professional associations whose memberships we recruited from). Our study population was based in Europe and Canada, limiting the ability to generalize results to other regions of the world; further research should include participants from other counties that are major users of research animals, including the USA and China.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-1-lan-10.1177_00236772211025166 for Attitudes of laboratory animal professionals and researchers towards carbon dioxide euthanasia for rodents and perceived barriers to change by Michael W Brunt, Lucia Améndola and Daniel M. Weary in Laboratory Animals

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-lan-10.1177_00236772211025166 for Attitudes of laboratory animal professionals and researchers towards carbon dioxide euthanasia for rodents and perceived barriers to change by Michael W Brunt, Lucia Améndola and Daniel M. Weary in Laboratory Animals

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the study participants and to Chereen Collymore, Jason Allen, Isabelle Desbaillets and Jean-Philippe Mocho for facilitating the distribution of the survey. We also thank Yasmin Ranjbar for her assistance with the qualitative analysis. MB is grateful to The Social Science and Humanities Research Council for the Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canadian Doctoral Scholarship.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: MB, LA, DW. Data Curation: MB, LA. Formal analysis: MB, LA. Methodology: MB, LA, DW. Project administration: MB, LA. Supervision: DW. Validation: MB, LA. Writing, original draft: MB, LA. Writing, review and editing: MB, LA, DW.

Data availability: All data is available in the supplementary materials.

ORCID iDs: Michael W Brunt https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9975-8684

Lucia Améndola https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0743-5117

Daniel M. Weary https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0917-3982

References

- 1.European Commission. 2019 report on the statistics on the use of animals for scientific purposes in the Member States of the European Union in 2015–2017. Report from The Commission to The European Parliament and The Council, 2020.

- 2.Canadian Council on Animal Care. CCAC animal data report. CCAC, Ottawa, 2018.

- 3.Canadian Council on Animal Care. CCAC guidelines on: Euthanasia of animals used in science. Ottawa: CCAC, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Off J Eur Union 2010; 53: 33–79. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leary S, Dewell R, Anthony R, et al. AVMA guidelines for the euthanasia of animals: 2020 edition. Schaumburg: American Veterinary Medical Association, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Research Council. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. 8th ed. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawkins P, Prescott MJ, Carbone L, et al. A Good Death? Report of the Second Newcastle Meeting on Laboratory Animal Euthanasia. Animals 2016; 6: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackshaw JK, Fenwick DC, Beattie AW. The behaviour of chickens, mice and rats during euthanasia with chloroform, carbon dioxide and ether. Lab Anim 1988; 22: 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Britt DP. The humaneness of carbon dioxide as an agent of euthanasia for laboratory rodents. In: Euthanasia of unwanted, injured or diseased animals or for educational or scientific purposes. Potters Bar: Universities Federation for Animal Welfare, 1987, pp. 19–31.

- 10.Turner PV, Hickman DL, van Luijk J, et al. Welfare impact of carbon dioxide euthanasia on laboratory mice and rats: A systematic review. Front Vet Sci 2020; 7: 411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Améndola L, Weary DM. Understanding rat emotional responses to CO2. Transl Psychiatry 2020; 10: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boivin GP, Hickman DL, Creamer-Hente MA, et al. Review of CO2 as a euthanasia agent for laboratory rats and mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 2017; 56: 491–499. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chisholm JM, Pang DSJ. Assessment of carbon dioxide, carbon dioxide/oxygen, isoflurane and pentobarbital killing methods in adult female Sprague-Dawley rats. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0162639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leach MC, Bowell VA, Allan TF, et al. Erratum: Aversion to gaseous euthanasia agents in rats and mice. Comp Med 2002; 52: 572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong D, Makowska IJ, Weary DM. Rat aversion to isoflurane versus carbon dioxide. Biol Lett 2013; 9: 6–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurst JL, West RS. Taming anxiety in laboratory mice. Nat Methods 2010; 7: 825–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson LJ, Smulders TV, Roughan JV. Identifying obstacles preventing the uptake of tunnel handling methods for laboratory mice: An international thematic survey. PLoS One 2020; 15: 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaFollette MR, Cloutier S, Brady C, et al. Laboratory animal welfare and human attitudes: A cross-sectional survey on heterospecific play or ‘rat tickling’. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0220580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patton MQ. Purposive sampling. In: Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 1990, pp. 169–186.

- 20.Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Heal 2000; 23: 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guest G, Macqueen KM, Namey EE. Validity and reliability (credibility and dependability) in qualitative research and data analysis. In: Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 2012, pp. 79–106.

- 23.Herzog HA. Gender differences in human–animal interactions: A review. Anthrozoos 2007; 20: 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips C, Izmirli S, Aldavood J, et al. An international comparison of female and male students’ attitudes to the use of animals. Animals 2011; 1: 7–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker JK, McGrath N, Nilsson DL, et al. The role of gender in public perception of whether animals can experience grief and other emotions. Anthrozoos 2014; 27: 251–266. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mueller JS, Melwani S, Goncalo JA. The bias against creativity: Why people desire but reject creative ideas. Psychol Sci 2012; 23: 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tourangeau R, Rips LJ, Rasinski KA. The psychology of survey response. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canadian Council on Animal Care. Terms of reference for animal care committees. CCAC, Ottawa, 2006.

- 29.Rosenberg S, Mosca J. Breaking down the barriers to organizational change. Int J Manag Inf Syst 2011; 15: 139. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-1-lan-10.1177_00236772211025166 for Attitudes of laboratory animal professionals and researchers towards carbon dioxide euthanasia for rodents and perceived barriers to change by Michael W Brunt, Lucia Améndola and Daniel M. Weary in Laboratory Animals

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-lan-10.1177_00236772211025166 for Attitudes of laboratory animal professionals and researchers towards carbon dioxide euthanasia for rodents and perceived barriers to change by Michael W Brunt, Lucia Améndola and Daniel M. Weary in Laboratory Animals