Abstract

The G2 DNA damage and DNA replication checkpoints in many organisms act through the inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdc2 on tyrosine-15. This phosphorylation is catalyzed by the Wee1/Mik1 family of kinases. However, the in vivo role of these kinases in checkpoint regulation has been unclear. We show that, in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Mik1 is a target of both checkpoints and that the regulation of Mik1 is, on its own, sufficient to delay mitosis in response to the checkpoints. Mik1 appears to have two roles in the DNA damage checkpoint; one in the establishment of the checkpoint and another in its maintenance. In contrast, Wee1 does not appear to be involved in the establishment of either checkpoint.

Checkpoints are mechanisms that allow cells to deal with DNA damage or other insults (10, 18). A major role of checkpoints is to delay cell cycle transitions, in order to allow time for the damage to be repaired. It is therefore important to understand how checkpoints regulate the basic cell cycle machinery. In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe and in mammalian cells, the DNA damage and DNA replication checkpoints arrest cells in G2 through inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdc2 on tyrosine-15 (5, 19, 35, 38). Cdc2, in association with its regulatory subunit cyclin B, is the kinase that determines the timing of the G2-M transition. While Cdc2 is controlled in many ways, the dephosphorylation of tyrosine-15 is the rate-limiting step for Cdc2 activation at mitosis and therefore regulates the timing of the G2-M transition (17, 20). This phosphorylation is catalyzed by members of the Wee1/Mik1/Myt1 family of tyrosine kinases (Wee1 and Myt1 in vertebrates and Wee1 and Mik1 in S. pombe) and removed by Cdc25 phosphatases (8). Thus, to regulate Cdc2 by tyrosine-15 phosphorylation, the checkpoints must increase its phosphorylation by one or more of the Wee1/Mik1/Myt1 kinases or decrease its dephosphorylation by Cdc25.

In fission yeast, the DNA damage and DNA replication checkpoints act through related signal transduction pathways that culminate in the serine/threonine kinase Chk1, the effector of the DNA damage checkpoint, or the serine/threonine kinase Cds1, the effector of the DNA replication checkpoint (reviewed in references 10, 36, and 37). In S. pombe and vertebrate cells, Cdc25 has been shown to be a target of these checkpoint pathways (4, 15, 21, 33, 38). Both Chk1 and Cds1 phosphorylate Cdc25 in vitro, and this phosphorylation inhibits its phosphatase activity (4, 14, 15, 21, 33, 40, 44). In addition, checkpoint-dependent phosphorylation of Cdc25 inhibits its nuclear import, presumably sequestering it away from Cdc2 (9, 22, 24, 43, 45). However, recent studies have shown that the regulation of Cdc25's subcellular localization is not required to enforce a checkpoint-dependent cell cycle delay (25). In S. pombe, Cdc2 is also dephosphorylated by the tyrosine phosphatase Pyp3 (28). Pyp3 plays a minor role in normal mitotic control, and unlike Cdc25, loss of its activity does not arrest the cell cycle. Therefore, Pyp3 cannot be a sufficient checkpoint target.

It has been less certain to what extent the regulation of the Wee1/Mik1/Myt1 kinases contributes to the function of the checkpoints. There have been several reports correlating checkpoint activation with changes in Wee1 abundance and phosphorylation. The degradation of exogenous Wee1 appears to be inhibited by the DNA replication checkpoint in Xenopus egg extracts (27). In S. pombe cell lysates, exogenous Wee1 is bound to and phosphorylated by Cds1 in a checkpoint-dependent manner (6). Wee1 has been reported to be phosphorylated in vivo in response to UV radiation, and it is also phosphorylated by Chk1 in vitro (32). However, none of these studies provide evidence that Wee1 regulation is important for checkpoint function in vivo.

Mik1 has also been proposed to be a target of the checkpoints. While Mik1 is not required for either checkpoint, cells deficient for both wee1 and cdc25 still arrest before mitosis in response to a replication block induced by hydroxyurea (HU), suggesting that regulation of Mik1 or Pyp3 is sufficient to enforce the replication checkpoint (11, 26). That Mik1 may play a role in this circumstance is suggested by the accumulation of Mik1 during a replication arrest. In response to the DNA replication checkpoint, mik1+ mRNA accumulates to high levels and Mik1 protein appears to be stabilized, leading to a dramatic increase in steady-state protein levels (1, 6, 7). Prolonged activation of the DNA damage checkpoint causes an increase in the steady-state level of Mik1 to a lesser extent, without affecting the level of mik1+ mRNA (1, 7). The increase in Mik1 abundance in response to prolonged exposure to DNA damage may explain how Mik1 acts to enforce the extended maintenance of a DNA damage checkpoint (1). Despite these correlations between Mik1 protein abundance and checkpoint activation, it is unknown if Mik1 regulation is involved in establishing a G2 delay in response to either checkpoint.

These studies on checkpoint regulation of Wee1 and Mik1 have led to models in which both kinases are proposed to be important targets of the checkpoints. We designed an experimental system to directly test these hypotheses. By using S. pombe strains in which Cdc25 is replaced with a phosphatase that is not regulated by the checkpoints, we created a situation in which any checkpoint regulation of Cdc2 phosphorylation must act through Wee1 or Mik1. This experimental system allowed us to examine the checkpoint regulation of Wee1 and Mik1 in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General methods for studying fission yeast were followed as described previously (29). The following strains were used: PR109 (h− leu1-32 ura4-D18), PR754 (h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 wee1-50 mik1::ura4+), NR1826 (h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 rad3::ura4+), NB2117 (h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 cds1::ura4+), AL2521 (h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 chk1+:9Myc), NR2648 (h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 rad3::ura4+ chk1+:9Myc), NR2613 (h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25::ura4+), NR2640 (h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25::ura4+ wee1-3x), NR2630 (h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25::ura4+ wee1-50ts), NR2657 (h+ leu1-32 ura4-? nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25::ura4+ mik1-s14ts), NR2634 (h− leu1-32 ura4-D18+ nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25::ura4+ mik1::ura4+), NR2644 (h− leu1-32 ura4-? nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25::ura4+ wee1-50 mik1-s14ts), NR2646 (h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25::ura4+ chk1+:9Myc), NR2650 (h− leul-32 ura4-D18 nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25::ura4+ mik1+:13Myc), KS1362 (h+ leu1-32 ura4-? wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts), and PR1928 (h− leu1-32 ura4-? wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts mik1::ura4). The designation “ura4-?” indicates that the ura4 allele may be ura4-D18 or ura4-294. Unless otherwise stated, strains were grown in Edinburgh minimal medium 2, supplemented with leucine, uracil, adenine, and histidine, with or without 5 μg of thiamine per ml at 32°C. For the experiments presented in Fig. 3, strains were grown in YES, a yeast extract-based medium with the same supplements. Strains were grown in the indicated media for at least 48 h before each experiment.

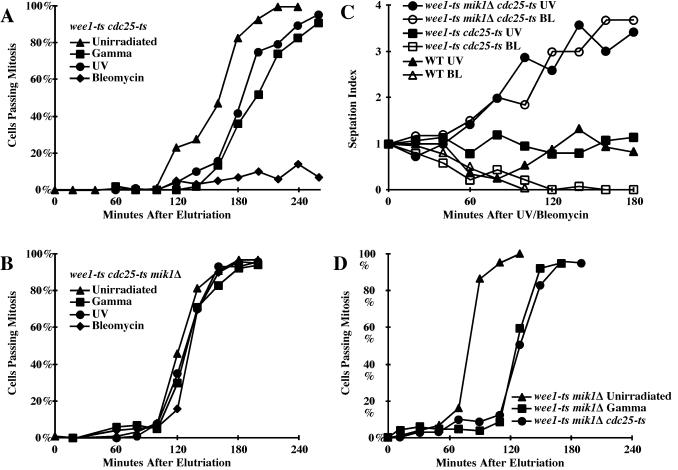

FIG. 3.

Mik1 is regulated by the DNA damage checkpoint. (A and B) wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts (KS1362), wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts mik1Δ (PR1928), and wee1-50ts mik1Δ (PR754) cells were elutriated and shifted to 35°C at 20 min. Cells were irradiated with 100 Gy of gamma radiation from 30 to 60 min, irradiated with 50 J/m2 at 60 min, or treated with 5 mU of bleomycin from 60 min. (C) Wild-type (PR109), wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts (KS1362), and wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts mik1Δ (PR1928) cells were grown at 25°C, shifted to 35°C for 40 min to inactivate wee1-50ts and cdc25-22ts, and irradiated with 100 J/m2 or treated with 2.5 U/of bleomycin per ml. Septation was monitored microscopically and normalized to the zero time point. The septation index of wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts mik1Δ cultures rises as the cells enter mitotic catastrophe (26). (D) wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts mik1Δ (PR1928) and wee1-50ts mik1Δ (PR754) cells were elutriated, irradiated with 100 Gy of gamma radiation from 0 to 30 min, and shifted to 35°C at 30 min.

Synchronous cultures were prepared by centrifugal elutriation with a Beckman JE-5.0 elutriation rotor, a technique that selects the smallest cells from an asynchronous population. In S. pombe, replication occurs immediately after mitosis and concurrently with cytokinesis; thus elutriation produces a population of early G2 cells. The time from elutriation to septation varies reproducibly among various strains, with that of the nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25::ura4+ strains being particularly short. Because all of the experiments were internally controlled, this variation does not affect the interpretation of the results. The number of cells having passed mitosis (N) was determined as N = (S + D)/(T − D), where S is the number of septated cells, D is the number of divided cells, and T is the total number of cells. This equation corrects for the fact that once a cell has divided it is counted as two cells. Cells were photographed and measured using a Quantix digital camera (Photometrics) and IP Lab software (Signal Analytics Corporation). Cells were irradiated with gamma radiation from a cesium-137 source at 3.3 Gy min−1 for 30 min, or at 1 Gy min−1 for the continuous exposure used in Fig. 1. For HU experiments, cells were grown for 60 to 90 min in 10 mM HU before elutriation. This protocol ensures that the elutriated cells are arrested in S phase. HU was then washed out of half the culture, which replicated and went on to divide with kinetics similar to that of untreated cultures.

FIG. 1.

Constitutive overexpression of Pyp3 rescues cdc25Δ. (A) Wild-type (PR109), nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ (NR2613), and nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ wee1-3x (NR2640) cells were grown in synthetic media lacking thiamine to induce high levels of expression of Pyp3 from the nmt1 promoter. The inset is the average length at septation for at least 50 cells, plus or minus the standard deviation. (B and C) wee1-50ts mik1Δ (PR754) and nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ wee1-50ts mik1-s14ts (NR2644) cells were grown at 25°C, elutriated to collect a synchronous population of cells, and shifted to 35°C. The irradiated cultures were continuously irradiated with gamma radiation at 1 Gy/min from 30 min before the shift. The HU-blocked cultures were grown in 10 mM HU for 60 min before elutriation, so that the elutriated cells would be blocked in S phase. Half of the culture was then released from the HU block and allowed to complete replication before the shift to 35°C. Cell cycle progression was monitored microscopically. For clarity, the data from the HU-released cultures is not shown, but those cultures divided with kinetics similar to that of the untreated cultures. The cell cycle kinetic data shown here and in the other figures are representative of at least three similar experiments.

The wee1-50 allele was used instead of wee1Δ because wee1Δ cells diploidize at a high frequency. wee1-50 strains were maintained at 25°C and shifted to 32°C for at least 12 h before any experiment conducted at 32°C. To establish that 32°C is a restrictive temperature for wee1-50, we compared the length of wee1-50 cells at various temperatures. wee1-50 cells at 32°C are indistinguishable from wee1Δ cells (Table 1). To determine if wee1-50 might have some residual activity at 32°C that would be unmeasurable at normal expression levels, we overexpressed wee1-50 approximately 30- to 60-fold from the adh1 promoter (our unpublished data). The normalized activity of wee1-50 at 32°C is less than 3%, assuming 30-fold overexpression (Table 1). In addition, all experiments with wee1-50 strains were repeated at 35°C with comparable results. Since wee1 mutant strains replicate later in the cell cycle than wild-type strains, we confirmed by flow cytometry that the synchronized cultures had completed replication before being irradiated (our unpublished data). The temperature-sensitive (ts) mik1-s14 allele was isolated on the basis of its synthetic lethality with wee1-50. It is tightly linked to mik1 and rescued by mik1+ genomic sequences (our unpublished data). The lowest restrictive temperature for mik1-s14, as assayed by viability of wee1Δ mik1-s14 cells, is 33°C. For the HU experiments involving mik1-s14, cells were grown and elutriated at 25°C and then cultured at 25°C for 60 min to allow the cells that had been washed out of HU to replicate. The cultures were then shifted to 35°C to inactivate Mik1.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of activities of length of S. pombe strains at various temperatures

| Strain | Temp (°C) | Size at septation (μm)a | Normalized Wee1 activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| PR109 wild type | 32 | 13.1 ± 1.1 | 1.0 |

| PR47 wee1Δ | 32 | 8.1 ± 0.9 | 0 |

| PR1080 wee1-50 | 25 | 10.5 ± 1.6 | 0.5 |

| PR1080 wee1-50 | 30 | 8.0 ± 1.0 | 0 |

| PR1080 wee1-50 | 32 | 8.2 ± 1.2 | 0 |

| PR1080 wee1-50 | 35 | 8.0 ± 1.6 | 0 |

| PR36 wee1-50 adh:wee1-50 | 25 | Arrested in G2 | NAb |

| PR36 wee1-50 adh:wee1-50 | 30 | 19.9 ± 2.6 | 0.08 |

| PR36 wee1-50 adh:wee1-50 | 32 | 12.4 ± 1.5 | 0.03 |

| PR36 wee1-50 adh:wee1-50 | 35 | 8.8 ± 1.0 | 0.005 |

Values are means ± standard deviations.

NA, not applicable.

The nmt1 promoter was inserted in place of the pyp3 promoter by one-step replacement. pFA6a-kanMX-P3nmt1 was amplified with the following primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc): 5′-GAATGTGAACGTGAACTAGATT ACGACTACAACTAGAAACTAGCGCTATGTGGGGGCCGTACAATGAT GATTTATTAAACGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC-3′ and 5′-ATAATCATG TACGCTTTTTCTTTTATTGTGATCAAGGGTGTTAGAACACCATTTTC TGTAGATACTTCTTTAAAAGACATGATTTAACAAAGCGACTATA-3′. The amplified DNA was transformed into PR109, and integrants were selected as described previously (2).

Protein affinity purifications, Western blotting, and kinase assays were performed as previously described (1, 6, 35).

RESULTS

Constitutive overexpression of pyp3+ rescues cdc25Δ.

We sought to create a strain of S. pombe in which the dephosphorylation of Cdc2 tyrosine-15 was not regulated by the checkpoints. To that end, we integrated the thiamine-repressible nmt1 promoter upstream of the pyp3+ genomic open reading frame. When grown in the absence of thiamine, nmt1:pyp3+ cells overexpress Pyp3 to a level sufficient to rescue the lethality of cdc25Δ (Fig. 1A). nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ cells are healthy and grow with a generation time of 3.0 h, similar to the wild type (data not shown). They divide at about 16 μm, compared with 13 μm for the wild type, suggesting that, at this level of expression, Pyp3 is not quite as active as endogenous Cdc25 (Fig. 1A). To demonstrate that the nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ cells are still responsive to variations in Wee1 activity, we used wee1-3x, an allele that has three copies of wee1+ integrated at its genomic locus (39). These cells divide at about 21 μm, the same length as otherwise-wild-type wee1-3x cells (39). Thus, in nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ cells, in which Pyp3 replaces Cdc25, the cells undergo mitosis with close-to-wild-type timing and retain a normal response to changes in Wee1 activity.

For our purposes it was important that the overexpressed Pyp3 not be regulated by either DNA damage or DNA replication checkpoints. To test whether the checkpoints regulate Pyp3, we adapted an assay that has been used to demonstrate the regulation of Cdc25 by the checkpoints (35). This assay uses a strain carrying ts alleles of wee1 and mik1 that is synchronized in early G2 by centrifugal elutriation. When this synchronous population of wee1-ts mik1-ts cells is shifted to 35°C, the two kinases are inactivated and Cdc2 can no longer be phosphorylated. The extent of tyrosine phosphorylation is then dependent only on the rate of dephosphorylation, which is predominantely catalyzed by Cdc25. Because dephosphorylation of Cdc2 is the rate-limiting step for entry into mitosis from G2, the rate at which Cdc2 is dephosphorylated can be inferred from the rate at which cells enter mitosis (17, 35). It takes wee1-ts mik1Δ cells about 40 min to dephosphorylate Cdc2 when shifted to 35°C, and the cells septate about 20 min later (Fig. 1B) (35). If either checkpoint is activated before the shift (by gamma radiation or by pretreatment of the cells with HU so that the elutriated cells are arrested in S phase), the dephosphorylation is delayed 40 to 60 min. These results demonstrate, as previously shown, that the dephosphorylation of Cdc2 by Cdc25 is inhibited by both checkpoints (Fig. 1B) (35, 38). When the experiments were repeated in an nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ wee1-ts mik1-ts strain, no delay in mitosis was observed, demonstrating that Pyp3 is not regulated by either checkpoint (Fig. 1C).

These results show that nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ cells are unable to regulate the rate of Cdc2 dephosphorylation in response to either checkpoint. Because both checkpoints are dependent on tyrosine-15 phosphorylation of Cdc2 (35, 38), any checkpoint regulation of mitosis in the nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ cells must be due to regulation of the rate of Cdc2 phosphorylation by Wee1 or Mik1. We used this situation to test if Wee1 or Mik1 is regulated by either checkpoint.

Regulation of Wee1 and Mik1 by the DNA damage checkpoint.

To determine whether Wee1 and Mik1 are regulated in response to activation of the checkpoint, we examined the ability of nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ cells to delay mitosis in response to DNA damage. A synchronous population of nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ cells was exposed to 100 Gy of gamma radiation in G2 and was monitored through the first mitosis. Wild-type cells delayed mitosis about 60 min in response to such treatment (Fig. 2A). nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ cells also showed a delay in G2, albeit a much reduced one, of about 20 min (Fig. 2B). A delay of this length was reproducibly seen in four similar experiments, and all other cell cycle kinetic results presented are representative of at least three similar experiments. This demonstrates that in the absence of Cdc25 regulation, cells are able to delay mitosis in response to DNA damage but not to the full extent seen in wild-type cells. We conclude that the regulation of either Wee1 or Mik1 must play a role in delaying mitosis in response to DNA damage.

FIG. 2.

The phosphorylation of Cdc2 by Mik1, but not Wee1, is up-regulated by the DNA damage checkpoint. (A through D) Wild-type (PR109), nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ (NR2613), nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ wee1-50ts (NR2630), and nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ mik1Δ (NR2634) cells were elutriated and irradiated with 100 Gy of gamma radiation from approximately 2 h before the midpoint of septation, as indicated by the bracket (irradiated), or mock irradiated (unirradiated). Cell cycle progression was monitored microscopically. (E) nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ mik1+:13Myc (NR2650) cells were grown to logarithmic phase and irradiated with 100 Gy of gamma radiation or incubated for 2 h with 10 mM HU. At indicated times, samples were taken and cleared whole-cell extracts were prepared. The extracts were analyzed by Western blotting with monoclonal anti-Myc antibodies (9E10; Covance). The slightly greater signal in the asynchronous sample compared with that in the irradiated samples is due to the small percentage of S-phase cells in the asynchronous sample, which produce higher levels of Mik1. (F) chk1+:9Myc (BF2521), rad3Δ chk1+:9Myc (NR2648), and nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ chk1+:9Myc (NR2646) cells were grown to logarithmic phase, irradiated with 100 Gy of gamma radiation, and analyzed as described for panel E.

We tested Wee1 and Mik1 individually by repeating the above experiment in wee1− or mik1− backgrounds. The partial delay seen in nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ cells is also seen in nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ wee1-ts cells at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 2C). In nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ wee1-ts cells, neither Cdc25 nor Wee1 can be regulated, and thus Mik1 regulation must be responsible for the delay observed. nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ mik1Δ cells, in which neither Cdc25 nor Mik1 can be regulated, are unable to delay mitosis in response to DNA damage (Fig. 2D). Thus, Wee1 is not significantly up-regulated in response to DNA damage, and Cdc25 and Mik1 are the only major targets controlling Cdc2 phosphorylation in response to the checkpoint.

The level of Mik1 protein has been reported to increase in response to DNA damage. We therefore tried to correlate the accumulation of Mik1 with the delay seen in nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ cells. Mik1 accumulated in response to prolonged checkpoint activation such as that evoked by continuous exposure to the DNA-damaging drug bleomycin or high doses of gamma radiation (250 Gy) (1, 7). However, Mik1 did not accumulate in response to the dose of gamma radiation (100 Gy) used in this study (Fig. 2E), presumably because this dose triggers only a relatively short delay which provides insufficient time for Mik1 to significantly accumulate (Fig. 2B). Thus, Mik1 activity must be regulated at some other level to induce the delay seen in nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ cells.

As a control, to show that overexpression of Pyp3 does not interfere with activation of the DNA damage signal transduction pathway, we examined the phosphorylation of Chk1. This phosphorylation results in a decrease in the mobility of Chk1 on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and correlates with the activation of the DNA damage checkpoint (42). Chk1 is phosphorylated normally in response to DNA damage in the nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ background, demonstrating that the checkpoint signal transduction pathway is intact (Fig. 2F).

As an alternate test of the function of Mik1 in the DNA damage checkpoint, we examined the checkpoint responses of cells lacking both Wee1 and Cdc25 functions. Cells mutated for both wee1 and cdc25 are viable but have severely compromised mitotic control and are thus difficult to synchronize (12, 34). However, by using the double-ts strain wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts, we were able to maintain and synchronize the cells at a permissive temperature and then to inactivate both Wee1 and Cdc25 by shifting the cells to a restrictive temperature. wee1-50ts and cdc25-22ts are both strong-ts alleles that are inactivated quickly and behave as null alleles at 35°C (12, 30, 39). If Mik1 is up-regulated by the DNA damage, wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts cells should show a DNA damage-induced delay of mitosis.

wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts cells were elutriated at 25°C, shifted to 35°C to inactivate Wee1 and Cdc25, and then treated with gamma radiation, UV radiation, or bleomycin, a gamma ray mimetic. In response to either radiation treatment the cells exhibited approximately a 20-min delay of mitosis, similar to the delay seen in the nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ background (Fig. 2A and 3A). In response to bleomycin, which causes persistent DNA damage, the cells delayed mitosis for the duration of the experiment. The delay seen in this strain is due to Mik1, since wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts mik1Δ cells fail to mitosis to any of the DNA-damaging agents (Fig. 3B). While the brief Cdc25-independent, Mik1-dependent delay induced by UV radiation in wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts cells is detectable in synchronized cultures, it is not obvious in asynchronous cultures (Fig. 3C). To more easily measure this delay in asynchronous cultures, we used bleomycin. As with the synchronous cultures, the Cdc25-independent delay is completely dependent on Mik1 (Fig. 3C).

The results obtained with the wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts mik1Δ strain allow another informative comparison. Because wee1-50ts mik1Δ cells cannot phosphorylate Cdc2 at 35°C, the rate at which they enter mitosis is dependent on the rate at which Cdc25 dephosphorylates Cdc2, that is, on the in vivo activity of Cdc25. Inactivation of Cdc25 by the DNA damage checkpoint delays the entry of wee1-50ts mik1Δ cells shifted to 35°C by about 40 min (35). We compared this amount of delay with that caused by inactivating Cdc25 with the cdc25-22ts allele. wee1-50ts mik1Δ cells were elutriated, irradiated with 100 Gy of gamma radiation or mock irradiated, and shifted to 35°C. The mitotic entry of these cells was graphed with that of wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts mik1Δ cells shifted to 35°C at the same amount of time after elutriation (Fig. 3D). The wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts mik1Δ cells and the irradiated wee1-50ts mik1Δ cells display the same kinetics of mitotic entry, demonstrating that, to a first approximation, the DNA damage checkpoint inhibits Cdc25 to the same extent as a strong-ts allele.

Regulation of Wee1 and Mik1 by the DNA replication checkpoint.

Next, we tested the DNA replication checkpoint response in nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ cells. We treated the asynchronous starting culture with HU for 90 min before elutriation. In this way, we could obtain a synchronous population arrested in S phase. HU was removed from half of the culture. This HU-released culture completes replication and goes on to divide with kinetics similar to that of an untreated culture. In wild-type cells, activation of the DNA replication checkpoint arrests cells for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 4A). Similarly, in nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ cells, the DNA replication checkpoint is able to arrest the majority of cells (Fig. 4B). Thus, either Wee1 or Mik1 must be up-regulated by the DNA replication checkpoint. To determine which one is regulated, we repeated the experiment for strains in which Wee1 or Mik1 is inactivated. HU inhibits mitosis in nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ wee1-ts cells at the restrictive temperature, suggesting that Wee1 is not significantly up-regulated in response to the DNA replication checkpoint (Fig. 4C). In contrast, nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ mik1-ts cells at the restrictive temperature fail to arrest (Fig. 4D). Therefore, Mik1 is up-regulated in response to the DNA replication checkpoint, and such up-regulation is sufficient to arrest most cells.

FIG. 4.

Phosphorylation of Cdc2 by Mik1, but not Wee1, is up-regulated by the DNA replication checkpoint. (A through D) Wild-type (PR109), nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ (NR2613), nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ wee1-50ts (NR2630), and nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ mik1-s14ts (NR2657) cells were grown for 60 to 90 minutes in 10 mM HU and elutriated to produce a synchronous culture arrested in S phase. Half of the culture was left in HU (HU blocked), while HU was washed out of the other half (HU released), which quickly went through DNA replication and then divided with kinetics similar to that of untreated cultures. Cell cycle progression was monitored microscopically. (E) Wild-type (PR109), cds1Δ (NB2117), rad3Δ (NR1826), nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ (NR2613), nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ wee1-50ts (NR2630), and nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ mik1Δ (NR2634) cells were grown to logarithmic phase and incubated for 4 h with 10 mM HU. Cds1 activity was assayed by its ability to bind and phosphorylate the amino terminus of Wee1 (6).

As a control, to show that overexpression of Pyp3 does not interfere with activation of the DNA replication checkpoint signal transduction pathway, we examined the activation of Cds1. As the most downstream event in the DNA replication checkpoint, the activation of Cds1 demonstrates that the checkpoint signal transduction pathway is intact (6, 23). As assayed by its ability to bind to and phosphorylate the amino terminus of Wee1 (6), Cds1 is activated normally in response to HU in nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ strains (Fig. 4E).

In the DNA replication checkpoint experiments, we used a ts allele of mik1 instead of a deletion. This was done because nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ mik1Δ cells divide soon after being arrested in S phase with HU. They divide sooner than normal, about 1 h after the previous division compared with 3 h for untreated cells, and they divide at a smaller size than normal, 11.1 ± 1.7 μm (mean ± standard deviation) compared with 17.4 ± 1.5 μm for untreated cells (data not shown). Checkpoint-defective rad3Δ cells behave similarly when treated with HU, dividing at 9.3 ± 0.9 μm when arrested in HU, compared with 13.2 ± 1.2 μm normally (data not shown). These results are consistent with the conclusion that nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ mik1Δ cells lack all the targets of the DNA replication checkpoint. Possible reasons for this accelerated division of checkpoint-defective cells in HU are discussed below.

In these experiments we used nmt:pyp3 to suppress the cell cycle arrest phenotype of cdc25Δ. Another plausible strategy is to use human T-cell PTPase to replace Cdc25. PTPase rescues cdc25Δ but has no sequence similarity to Cdc25 (16). Thus, it is unlikely to be regulated by the checkpoints in S. pombe. We performed the synchronous-checkpoint experiments illustrated in Fig. 2 and 4 in an nmt1:PTPase background and obtained comparable results (our unpublished data). However, for technical reasons we had to use a cdc25-ts allele instead of cdc25Δ, and we were unable to do the controls shown in Fig. 1. We therefore used nmt1:pyp3 for the experiments described in this paper.

DISCUSSION

We constructed strains of S. pombe in which a checkpoint delay of mitosis in response to DNA damage or a DNA replication block can act only through Wee1 or Mik1. We did this by replacing Cdc25, the phosphatase that normally dephosphorylates Cdc2, with overexpressed Pyp3, another Cdc2 phosphatase that is not regulated by either checkpoint. Since the G2 checkpoints in S. pombe act through the tyrosine-15 phosphorylation of Cdc2 (35, 38), this situation leaves Wee1 and Mik1 as the remaining possible targets of the checkpoints and allows us to assay the regulation of Wee1 and Mik1 in the absence of confounding regulation of Cdc25.

Experiments with these strains show that Mik1 is regulated by both checkpoints. Mik1 regulation in response to the DNA replication checkpoint is sufficient to arrest most cells in G2, independent of checkpoint regulation of Cdc25 (Fig. 4C). This regulation may be due to the large increase in Mik1 protein levels in response to the replication checkpoint (6, 7), although the specific activity of Mik1 may also be regulated. Cdc25 regulation is also able to arrest cells independent of Mik1 activity (26). The fact that some cells leak through the arrest in the nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ background, while mik1Δ cells arrest tightly in HU, suggests that Cdc25 is a somewhat more important target. However, both Mik1 and Cdc25 appear to be major targets of the DNA replication checkpoint in S. pombe.

Mik1 regulation plays a less important role in the DNA damage checkpoint. nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ cells and wee1-50ts cdc25-22ts cells have an attenuated DNA damage checkpoint, delaying mitosis by less than 20 min in response to damage that arrests wild-type cells for 60 min (Fig. 2A and B and 3A). This delay is dependent upon Mik1 (Fig. 2D and 3B). Mik1 has also been shown to be required for prolonged arrest in response to continuous DNA damage (1). However, the effect described in that work is different from the one described here. In that work, mik1Δ cells still arrested but were unable to maintain a prolonged arrest in the presence of continuous damage. Here, we show that in response to a short pulse of DNA damage, mik1Δ cells that are also cdc25Δ are unable to establish a checkpoint (Fig. 2D and 3B). Conversely, cells that lack Cdc25 but retain Mik1 can establish a checkpoint but cannot maintain it for as long as wild-type cells (Fig. 2A and B and 3A).

These two roles for Mik1, one in establishment and the other in maintenance of the checkpoint, may be due to different modes of Mik1 regulation. The requirement of Mik1 in maintaining a prolonged DNA damage checkpoint correlates with increased abundance of Mik1 (1). In contrast, the short duration of checkpoint used in this work is insufficient to cause Mik1 accumulation (Fig. 2E). These results suggest that Mik1 activity is up-regulated immediately by a mechanism independent of protein level and that this up-regulation is able to cause a brief delay of mitosis. If the damage persists, Mik1 protein levels increase, and this increase may be important for maintenance of a prolonged arrest. Therefore, there may be two modes of regulation of Mik1 in response to the DNA damage checkpoint: one that increases Mik1 activity immediately to establish the checkpoint and another that increases Mik1 abundance over time to maintain the checkpoint. Both modes of regulation are dependent on Chk1, as demonstrated by the fact that the checkpoint is abolished in chk1Δ cells. It is plausible that Chk1 acts in both cases through the direct phosphorylation of Mik1. Alternatively, Chk1 may regulate Mik1 indirectly.

In contrast to Mik1, Wee1 does not appear to be required for the establishment of either checkpoint. The presence of Wee1, in the absence of Mik1, is not sufficient to effect a mitotic delay in response to either DNA damage or replication inhibition (Fig. 2D, 3B, and 4D). Were Wee1 up-regulated even threefold, it would be readily apparent, as demonstrated by the effect of adding two copies of wee1+ to the nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ background (Fig. 1A). The different effects of the wee1 and mik1 mutations on checkpoint control in the nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ background contrast sharply with the fact that during a normal cell cycle, cells are quite sensitive to mutations in wee1 but not sensitive to mutations in mik1 (13, 26). Thus it appears that Wee1 is the more important kinase under normal growth conditions, while Mik1 is the more important kinase in checkpoint situations. Previous work has shown that Wee1 binds to and is phosphorylated by Cds1 in response to activation of the replication checkpoint (6). These results lead to the hypothesis that Wee1 is an important target of the replication checkpoint. The experiments presented here, undertaken in large part to test that hypothesis, do not support an important role for Wee1 regulation in establishment of the replication checkpoint. However, while Wee1 does not appear to be regulated by either checkpoint, it should be noted that these experiments were designed to assay specifically the establishment of the checkpoints. In addition to checkpoint establishment, the maintenance of and adaptation to checkpoints are also regulated (1, 41). It is possible that Wee1 could be regulated at some other point in the checkpoint cycle.

A recently published study, using approaches similar to some of the ones described here, has reached a different conclusion regarding the role of Wee1 in the DNA damage checkpoint (34). Raleigh and O'Connell conclude that Wee1 is regulated by the DNA damage checkpoint. They present two sets of experiments examining cell cycle kinetics in response to DNA damage that support their conclusions. First, they demonstrate that cells lacking Cdc25 but viable due to either the expression of human T-cell PTPase or the presence of a suppressing mutation in cdc2 can delay mitosis in response to DNA damage. These results are similar to those presented here and elsewhere and support the conclusion that there is a target other than Cdc25 (Fig. 2B) (1). For these experiments, Raleigh and O'Connell used synchronous cultures and were able to detect a brief Cdc25-independent delay, similar to the one seen in Fig. 2. They then base their conclusion that Wee1 is the other target on the fact that strains lacking functional Wee1 and Cdc25 display no DNA damage-induced delay of mitosis. However, they use only asynchronous cultures for these experiments and are therefore unable to detect the Cdc25- and Wee1-independent delay seen in Fig. 2 and 3. Previous experiments with asynchronous cultures have also failed to detect the attenuated Mik1-dependent DNA damage checkpoint delay in cdc25− strains. In fact, when we originally investigated the role of Cdc25 in the DNA damage checkpoint, we used asynchronous cultures and were unable to detect any Cdc25-independent checkpoint delay (15). The attenuated Mik1-dependent delay is apparent only when the experiments are done with synchronous cultures (Fig. 2B and 3A) (1). Thus, the asynchronous experiments presented by Raleigh and O'Connell and reproduced in Fig. 3C, would not be expected to detect the Cdc25-independent delay that they had identified in their synchronous experiments. Moreover, a prolonged checkpoint delay that can be seen in asynchronous cultures is induced by bleomycin in cells lacking functional Cdc25 and Wee1 (Fig. 3A and C), and this arrest is entirely dependent on Mik1 (Fig. 3B and C).

Our conclusion that the checkpoint up-regulates Mik1 has the positive attribute of providing a straightforward explanation for why wee1 mutations suppress mutational inactivation of Cdc25 and yet wee1 mutants are fully checkpoint proficient (3, 12, 39). If the damage checkpoint regulated only Wee1 and Cdc25, as proposed by Raleigh and O'Connell, then wee1 mutations should suppress cell cycle arrest caused by negative regulation of Cdc25 by Chk1. On the other hand, if the damage checkpoint up-regulates Mik1, wee1 mutants should undergo checkpoint arrest in response to DNA damage, as in fact they do.

In the course of the DNA replication checkpoint experiments, we discovered that nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ mik1Δ cells, when grown in HU, greatly advance the timing of mitosis. nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ mik1Δ cells placed in HU during G2 will grow to about 16 μm, the normal size for mitosis, divide, and then attempt to replicate. Because of HU, the cells will arrest in early S phase. Up to this point, nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ mik1Δ cells behave in the same way as wild-type cells. However, instead of delaying mitosis as wild-type cells would, nmt1:pyp3+ cdc25Δ mik1Δ cells divide again. In fact, they divide sooner than normal, and consequently, they divide at a smaller than normal size. Because cdc25 and mik1 are both deleted, Wee1 remains as the sole major regulator of mitotic timing. Thus, one might conclude that the DNA replication checkpoint down-regulates Wee1 in order to advance mitosis. However, this explanation runs counter to the idea that the checkpoint should delay mitosis and, if anything, up-regulate Wee1. We therefore prefer an alternate explanation based upon the proposed role of Wee1 in size control.

The size of S. pombe cells at mitosis is proportional to ploidy, with 4C cells being roughly twice as big as 2C cells (31). It has been proposed that this mitotic size control acts through the regulation of Wee1 (13). This model predicts that a cell arrested in HU with a 1C DNA content and lacking a DNA replication checkpoint would divide at about half the size of a normal 2C cell, since it has half the ploidy of a 2C cell. Thus, the advancement of mitosis in nmt1:pyp3+ cdc2.5Δ mik1Δ cells could be due not to the direct down-regulation of Wee1 by the DNA replication checkpoint but rather to the down-regulation of Wee1 as a result of the fact that the cells are past the size for mitosis of a 1C cell. Consistent with this idea, checkpoint-deficient rad3Δ cells also advance mitosis when treated with HU. rad3Δ cells are thought to entirely lack the DNA replication checkpoint; thus, the fact that they advance mitosis is inconsistent with a model in which the checkpoint directly down-regulates Wee1.

The results of this study, along with previous work on Cdc25 regulation, define the major in vivo cell cycle targets of the G2 DNA damage and DNA replication checkpoints in S. pombe (Fig. 5). The DNA damage checkpoint, acting through its effector, Chk1, strongly inhibits Cdc25, to approximately the same extent as a strong-ts allele (Fig. 3C) (15, 35). We show here that, in the absence of this regulation of Cdc25, regulation of Mik1 can cause an attenuated mitotic delay (Fig. 2B and D and 3A and B). These results show that Cdc25 is the major target of the DNA damage checkpoint, with Mik1 as a secondary target, consistent with previous reports that Cdc25 is the major target of the DNA damage checkpoint (1, 15). In contrast, both Cdc25 and Mik1 are major targets of the DNA replication checkpoint. The ability of Cdc25 to dephosphorylate Cdc2 in vivo is inhibited by the DNA replication checkpoint, and this inhibition is sufficient to delay mitosis in the absence of Mik1 (26, 38). Conversely, Mik1 up-regulation in response to the DNA replication checkpoint is also sufficient to delay mitosis in most cells (Fig. 4B and D). The fact that cells lacking both Cdc25 and Mik1 are unable to delay mitosis in response to either DNA damage or a replication block demonstrates that they are the only major cell cycle targets of the two checkpoints (Fig. 2D, 3B, and 4D).

FIG. 5.

Model for the regulation of mitosis by the G2 DNA replication checkpoints. Initiation of mitosis is controlled by the tyrosine dephosphorylation of Cdc2. The timing of this dephosphorylation is regulated by a balance between the activities of the Wee1 and Mik1 tyrosine kinases on one hand and the activity of the Cdc25 phosphatases on the other. In order to delay mitosis, the G2 DNA damage and DNA replication checkpoints, acting through their effector kinases, Chk1 and Cds1, regulate both Cdc25 and Mik1. Chk1 inhibits the dephosphorylation of Cdc2 by phosphorylating and inhibiting Cdc25. In addition, Chk1 up-regulates Mik1 in two separate ways. It does so as an immediate response to the checkpoint, and this up-regulation is important for checkpoint establishment. It also leads to the accumulation of Mik1 protein during prolonged checkpoints, and this accumulation may be important for checkpoint maintenance. The role of Mik1 regulation in the establishment of the DNA damage checkpoint is minor compared with that of Cdc25, as indicated by the dashed arrow. In a manner similar to that of Chk1, Cds1 inhibits the dephosphorylation of Cdc2 by phosphorylating and inhibiting Cdc25. Cds1 also up-regulates Mik1, but to a much greater extent than Chk1. The up-regulation by Cds1 correlates with, and is presumably due to, high levels of Mik1 accumulation in DNA replication-arrested cells.

Fission yeast cells have provided an excellent model for framing checkpoint studies in more complex multicellular organisms. Indeed, Cdc25 was first identified as a checkpoint target through investigations of fission yeast cells, and it is now evident that regulation of Cdc25 by Chk1 is substantially conserved among fission yeast cells, mammalian cells, and Xenopus oocytes (15, 21, 33, 35, 40). These facts raise the question of whether Wee1/Mik1 homologs are checkpoint targets in multicellular organisms. As experiments aiming to answer this question go forward, it will be important to keep in mind that mammalian and Xenopus Wee1 protein sequences are equally related to Wee1 and Mik1 in fission yeast cells. Thus, it is possible that human Wee1 may be functionally more similar to Mik1 than Wee1 in fission yeast cells. As we learn more about how Mik1 is regulated by checkpoints in fission yeast cells and are able to compare this knowledge to studies of Wee1/Mik1-related genes in other species, a better understanding of the functional distinctions between Wee1 and Mik1 will emerge.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Kathy Gould for providing the nmt1:PTPase construct with which preliminary experiments were done, Michael Boddy for providing the glutathione S-transferase Wee1, and Beth Baber-Furnari for providing the chk1+:9Myc strain. We also thank the members of the TSRI Cell Cycle Group for many interesting discussions and useful suggestions, in particular Jean-Marc Brondello for suggesting the use of a conditional mik1 allele.

N.R. was supported by an NIH postdoctoral fellowship and a special fellowship from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. This work was supported by an NIH grant awarded to P.R.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baber-Furnari B A, Rhind N, Boddy M N, Shanahan P, Lopez-Girona A, Russell P. Regulation of mitotic inhibitor mik1 helps to enforce the DNA damage checkpoint. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:1–11. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bähler J, Wu J Q, Longtine M S, Shah N G, McKenzie III A, Steever A B, Wach A, Philippsen P, Pringle J R. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 1998;14:943–951. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YEA292>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbet N C, Carr A M. Fission yeast wee1 protein kinase is not required for DNA damage-dependent mitotic arrest. Nature. 1993;364:824–827. doi: 10.1038/364824a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blasina A, de Weyer I V, Laus M C, Luyten W H, Parker A E, McGowan C H. A human homologue of the checkpoint kinase Cds1 directly inhibits Cdc25 phosphatase. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blasina A, Paegle E S, McGowan C H. The role of inhibitory phosphorylation of CDC2 following DNA replication block and radiation-induced damage in human cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1013–1023. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.6.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boddy M N, Furnari B, Mondesert O, Russell P. Replication checkpoint enforced by kinases Cds1 and Chk1. Science. 1998;280:909–912. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen P U, Bentley N J, Martinho R G, Nielsen O, Carr A M. Mik1 levels accumulate in S phase and may mediate an intrinsic link between S phase and mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2579–2584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman T R, Dunphy W G. Cdc2 regulatory factors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:877–882. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalal S N, Schweitzer C M, Gan J, DeCaprio J A. Cytoplasmic localization of human cdc25C during interphase requires an intact 14-3-3 binding site. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4465–4479. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elledge S J. Cell cycle checkpoints: preventing an identity crisis. Science. 1996;274:1664–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enoch T, Carr A M, Nurse P. Fission yeast genes involved in coupling mitosis to completion of DNA replication. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2035–2046. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.11.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fantes P. Epistatic gene interactions in the control of division in fission yeast. Nature. 1979;279:428–430. doi: 10.1038/279428a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fantes P A, Nurse P. Control of the timing of cell division in fission yeast. Cell size mutants reveal a second control pathway. Exp Cell Res. 1978;115:317–329. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(78)90286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furnari B, Blasina A, Boddy M N, McGowan C H, Russell P. Cdc25 inhibited in vivo and in vitro by checkpoint kinases Cds1 and Chk1. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:833–845. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furnari B, Rhind N, Russell P. Cdc25 mitotic inducer targeted by Chk1 DNA damage checkpoint kinase. Science. 1997;277:1495–1497. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gould K L, Moreno S, Tonks N K, Nurse P. Complementation of the mitotic activator, p80cdc25, by a human protein-tyrosine phosphatase. Science. 1990;250:1573–1576. doi: 10.1126/science.1703321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gould K L, Nurse P. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the fission yeast cdc2+ protein kinase regulates entry into mitosis. Nature. 1989;342:39–45. doi: 10.1038/342039a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartwell L H, Weinert T A. Checkpoints: controls that ensure the order of cell cycle events. Science. 1989;246:629–634. doi: 10.1126/science.2683079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin P, Gu Y, Morgan D O. Role of inhibitory CDC2 phosphorylation in radiation-induced G2 arrest in human cells. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:963–970. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krek W, Nigg E A. Mutations of p34cdc2 phosphorylation sites induce premature mitotic events in HeLa cells: evidence for a double block to p34cdc2 kinase activation in vertebrates. EMBO J. 1991;10:3331–3341. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumagai A, Guo Z, Emami K H, Wang S X, Dunphy W G. The Xenopus Chk1 protein kinase mediates a caffeine-sensitive pathway of checkpoint control in cell-free extracts. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:1559–1569. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.6.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumagai A, Yakowec P S, Dunphy W G. 14-3-3 proteins act as negative regulators of the mitotic inducer Cdc25 in Xenopus egg extracts. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:345–354. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindsay H D, Griffiths D J, Edwards R J, Christensen P U, Murray J M, Osman F, Walworth N, Carr A M. S-phase-specific activation of Cds1 kinase defines a subpathway of the checkpoint response in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Dev. 1998;12:382–395. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.3.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez-Girona A, Furnari B, Mondesert O, Russell P. Nuclear localization of Cdc25 is regulated by DNA damage and a 14-3-3 protein. Nature. 1999;397:172–175. doi: 10.1038/16488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Girona, A., J. Kanoh, and P. Russell. Regulated localization of Cdc25 is not required for DNA damage checkpoint control. Curr. Biol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Lundgren K, Walworth N, Booher R, Dembski M, Kirschner M, Beach D. Mik1 and Wee1 cooperate in the inhibitory tyrosine phosphorylation of Cdc2. Cell. 1991;64:1111–1122. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michael W M, Newport J. Coupling of mitosis to the completion of S phase through Cdc34-mediated degradation of Wee1. Science. 1998;282:1886–1889. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Millar J B A, Lenaers G, Russell P. Pyp3 PTPase acts as a mitotic inducer in fission yeast. EMBO J. 1992;11:4933–4941. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nurse P. Genetic control of cell size at cell division in yeast. Nature. 1975;256:547–551. doi: 10.1038/256547a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nurse P, Thuriaux P. Regulatory genes controlling mitosis in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 1980;96:627–637. doi: 10.1093/genetics/96.3.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Connell M J, Raleigh J M, Verkade H M, Nurse P. Chk1 is a wee1 kinase in the G2 DNA damage checkpoint inhibiting cdc2 by Y15 phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1997;16:545–554. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.3.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng C Y, Graves P R, Thoma R S, Wu Z, Shaw A S, Piwnica-Worms H. Mitotic and G2 checkpoint control: regulation of 14-3-3 protein binding by phosphorylation of Cdc25C on serine-216. Science. 1997;277:1501–1505. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raleigh J M, O'Connell M J. The G2 DNA damage checkpoint targets both Wee1 and Cdc25. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:1727–1736. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.10.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhind N, Furnari B, Russell P. Cdc2 tyrosine phosphorylation is required for the DNA damage checkpoint in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 1997;11:504–511. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhind N, Russell P. Chk1 and Cds1: linchpins of the DNA damage and replication checkpoint pathways. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3889–3896. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.22.3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhind N, Russell P. Mitotic DNA damage and replication checkpoints in yeast. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80118-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhind N, Russell P. Tyrosine phosphorylation of Cdc2 is required for the replication checkpoint in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3782–3787. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Russell P, Nurse P. Negative regulation of mitosis by wee1+, a gene encoding a protein kinase homolog. Cell. 1987;49:559–567. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90458-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanchez Y, Wong C, Thoma R S, Richman R, Wu Z, Piwnica-Worms H, Elledge S J. Conservation of the Chk1 checkpoint pathway in mammals: linkage of DNA damage to Cdk regulation through Cdc25. Science. 1997;277:1497–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Toczyski D P, Galgoczy D J, Hartwell L H. CDC5 and CKII control adaptation to the yeast DNA damage checkpoint. Cell. 1997;90:1097–1106. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walworth N C, Bernards R. rad-dependent response of the chk1-encoded protein kinase at the DNA damage checkpoint. Science. 1996;271:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang J, Winkler K, Yoshida M, Kornbluth S. Maintenance of G2 arrest in the Xenopus oocyte: a role for 14-3-3-mediated inhibition of Cdc25 nuclear import. EMBO J. 1999;18:2174–2183. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeng Y, Forbes K C, Wu Z, Moreno S, Piwnica-Worms H, Enoch T. Replication checkpoint requires phosphorylation of the phosphatase Cdc25 by Cds1 or Chk1. Nature. 1998;395:507–510. doi: 10.1038/26766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeng Y, Piwnica-Worms H. DNA damage and replication checkpoints in fission yeast require nuclear exclusion of the Cdc25 phosphatase via 14-3-3 binding. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7410–7419. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]