Abstract

Background

Aberrant splicing is a common outcome in the presence of exonic or intronic variants that might hamper the intricate network of interactions defining an exon in a specific gene context. Therefore, the evaluation of the functional, and potentially pathological, role of nucleotide changes remains one of the major challenges in the modern genomic era. This aspect has also to be taken into account during the pre-clinical evaluation of innovative therapeutic approaches in animal models of human diseases. This is of particular relevance when developing therapeutics acting on splicing, an intriguing and expanding research area for several disorders. Here, we addressed species-specific splicing mechanisms triggered by the OTC c.386G>A mutation, relatively frequent in humans, leading to Ornithine TransCarbamylase Deficiency (OTCD) in patients and spfash mice, and its differential susceptibility to RNA therapeutics based on engineered U1snRNA.

Methods

Creation and co-expression of engineered U1snRNAs with human and mouse minigenes, either wild-type or harbouring different nucleotide changes, in human (HepG2) and mouse (Hepa1-6) hepatoma cells followed by analysis of splicing pattern. RNA pulldown studies to evaluate binding of specific splicing factors.

Results

Comparative nucleotide analysis suggested a role for the intronic +10-11 nucleotides, and pull-down assays showed that they confer preferential binding to the TIA1 splicing factor in the mouse context, where TIA1 overexpression further increases correct splicing. Consistently, the splicing profile of the human minigene with mouse +10-11 nucleotides overlapped that of mouse minigene, and restored responsiveness to TIA1 overexpression and to compensatory U1snRNA. Swapping the human +10-11 nucleotides into the mouse context had opposite effects.

Moreover, the interplay between the authentic and the adjacent cryptic 5′ss in the human OTC dictates pathogenic mechanisms of several OTCD-causing 5′ss mutations, and only the c.386+5G>A change, abrogating the cryptic 5′ss, was rescuable by engineered U1snRNA.

Conclusions

Subtle intronic variations explain species-specific OTC splicing patterns driven by the c.386G>A mutation, and the responsiveness to engineered U1snRNAs, which suggests careful elucidation of molecular mechanisms before proposing translation of tailored therapeutics from animal models to humans.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s10020-021-00418-9.

Keywords: OTC deficiency, Pathogenic mRNA splicing, Spfash mouse model, Nucleotide variations, U1snRNA

Background

Among the several mechanisms contributing to the complexity of the metazoan transcriptome, pre-mRNA splicing plays a central role (Nilsen and Graveley 2010). A pre-mRNA can undergo splicing through different pathways (alternative splicing; AS), which increases the variety of transcripts and potential protein isoforms, with pathophysiological and evolutionary implications (Merkin et al. 2012). Consistently, as the evolutionary distance from primates increases, the number of AS events decreases (Kim et al. 2007; Barbosa-Morais et al. 2012). Most AS is guided by cis-specific regulatory elements, located within exons and introns (Baralle and Baralle 2018). While the evolution of nucleotide variations can be evaluated by comparative genomic and RNAseq analyses, the study of their functional relevance across species, represents a major issue. This aspect, hardly predictable and so far poorly investigated, has to be taken into account also when exploring RNA therapeutics in animal models in the attempt to translate pre-clinical data into humans. RNA therapeutics consist of the viral or lipid-nanoparticle mediated delivery of engineered RNA to treat or prevent diseases, and has led to recent breakthrough innovations (Polack et al. 2020). Among molecules acting at RNA levels, engineered variants of the U1snRNA, the RNA component of the spliceosomal U1 ribonucleoprotein (U1snRNP) mediating 5′ss recognition and thus exon definition in the earliest splicing steps (De Conti et al. 2013), have proven to be effective in modulating splicing for therapeutic purposes. In particular, U1snRNA variants with increased complementarity with the 5′ss of the defective exon (named compensatory U1snRNA), or targeting the downstream intronic sequences (named Exon specific U1snRNA, ExSpeU1), have demonstrated their ability to rescue exon skipping caused by different types of mutations in cellular and animal models of several human diseases (Donadon et al. 2018, 2019; Scalet et al. 2018, 2019; Yamazaki et al. 2018; Balestra et al. 2019a, 2020a; Lee et al. 2019; Donegà et al. 2020; Martín et al. 2021).

A paradigmatic example is provided in Ornithine TransCarbamylase (OTC) deficiency (OMIM 311250), the most frequent (1:40.000–70.000) disease of the urea cycle in humans. The spfash mouse model carries the mutation c.386G>A; p.R129H (NP_000522) at the last position of OTC (NG_008471) exon 4 that has been also found in several patients with OTC deficiency (OTCD) (Tuchman et al. 2002; Yamaguchi et al. 2006; Rivera-Barahona et al. 2015). Studies in mice indicated that the p.R129H amino acid change does not impair OTC activity (Hodges and Rosenberg 1989; Zimmer et al. 1999), but the c.386G>A nucleotide change affects splicing. Noticeably, the degree of splicing impairment by the c.386G>A mutation substantially differs in humans and mice (Rivera-Barahona et al. 2015): in humans the pathogenic splicing pattern is characterized by exon 4 skipping and usage of a cryptic 5′ss at c.386+5 position, with only trace levels of correct transcripts; in mice the nucleotide change leads to exon 4 skipping and usage of an intronic cryptic 5′ splice site (ss) at c.386+49 position but it is also associated with appreciable levels of correct transcripts, accounting for hepatic OTC activity (5–10% of WT) and a mild phenotype.

These differences offer the opportunity for a deep investigation of the functional relevance of species-specific gene variations. Moreover, they could affect correction efficiency of U1snRNA variants designed to force exon 4 inclusion, which we showed to be capable to efficiently rescue OTC expression at both RNA and protein levels in the spfash mouse model (Balestra et al. 2020a).

Here, we dissected the molecular mechanisms underlying the specie-specific OTC exon 4 splicing pattern and demonstrated the key role of subtle intronic changes downstream of the authentic exon 4 5′ss, which also explain a differential responsiveness to RNA-based correction based on engineered U1snRNA.

Methods

Expression vectors and splicing assays

To create the human OTC minigene (OTCh), the genomic region of human OTC gene (NG_008471) including the last 535 bp of intron 3, exon 4 (88 bp) and the first 681 bp of intron 4 was amplified from the DNA of a healthy subject using high-fidelity PfuI DNA-Polymerase (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and primers hOTCF and hOTCR, and subsequently cloned into the pTB (41) by exploiting the NdeI restriction site inserted within primers. The mouse OTC minigene (OTCm) was available from previous studies (Balestra et al. 2020a). Nucleotide changes were introduced into the human and mouse OTC minigenes by mutagenesis (Balestra et al. 2020a). Expression vectors for the U1snRNA variants were created as previously reported (Balestra et al. 2015).

Human (HepG2) and mouse (Hepa1-6) hepatoma cells were cultured and seeded in 12-well plates and transiently transfected with one microgram of each expression vectors using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), as previously described (Ferraresi et al. 2020). Twenty-four hours post-transfection the total RNA was isolated with Trizol (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), reverse transcribed and amplified with primers Alpha and Bra oligonucleotides designed on the upstream and downstream exons, respectively. The PCR was run for 40 cycles at the following conditions: 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 56 °C and 40 s at 72 °C. Amplicons were resolved on 2.5% agarose gel, and bands analyzed by densitometry through the UVITEC software (Cleaver Scientific, Warwickshire, UK). For denaturing capillary electrophoresis analysis, the fragments were fluorescently labeled by using primer Bra2 labeled with FAM and run on an ABI-3100 instrument, followed by analysis of peaks.

All constructs and transcript amplicons were validated by direct sequencing. Sequences of oligonucleotides are provided as Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2.

All data reported are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and derive from at least three independent experiments.

Computational analysis

Computational prediction of splice sites was conducted by using the Human Splicing Finder (http://www.umd.be/HSF/) tool.

The minimum free energy (MFE) of the interaction between the U1snRNA and donor splice site has been calculated by exploiting the RNAcofold Server (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAWebSuite/RNAcofold.cgi) and using the 11-bp long sequence of 5′tail of U1snRNA and the targeted 5′ss as inputs.

Pulldown assays

To affinity purify RNA-binding proteins, 100 pmol of 3′-biotin-coupled RNA oligonucleotides (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) were incubated with 24 µg of HeLa nuclear extract (Ipracell, Mons, Belgium) and protease inhibitor cocktail (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in TENT buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 250 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 7.5) for 30 min at room temperature (20–25 °C). RNA–protein complexes were bound with 50 µg of streptavidin-coated magnetic beads (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and washed with TENT buffer. Proteins were eluted with SDS sample buffer and analyzed by Western blotting with monoclonal mouse anti-TIA1 (0TI1D7, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), polyoclonal mouse anti-Sam68 (PA5-62364, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), monoclonal anti-GAPDH (ZG003, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and then with polyclonal goat anti-mouse HRP-conjugated (P0447, Dako, Jena, DE) antibodies. All RNA oligonucleotides are available in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Results

Nucleotide variations at +10-11 positions dictate species-specific splicing patterns

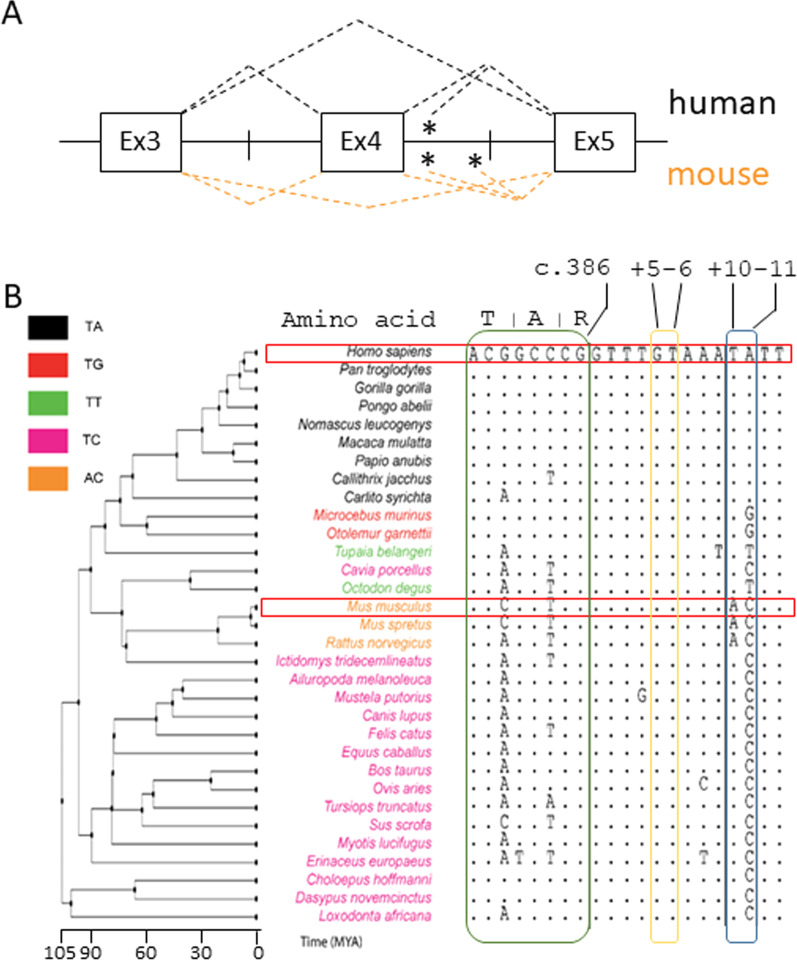

To infer the mechanisms underlying the remarkably different splicing patterns triggered by the OTC c.386G>A mutation in humans and mouse (Fig. 1A) (Rivera-Barahona et al. 2015) we performed a sequence alignment of OTC exon 4 and the surrounding introns across species (Fig. 1B). Comparison of human and mouse sequences involving the authentic and the adjacent cryptic 5′ss reveals divergence at positions +10-11, corresponding to positions +6-7 of the cryptic 5′ss. In particular, nucleotide +10 is highly conserved among species, but in rodents, and adenine at +11 position characterizes primates. These variations are predicted to impact on the complementarity with the U1snRNA (Fig. 2A), which is higher in humans than in mice due to mismatches at positions +10-11.

Fig. 1.

Species-specific splicing patterns and comparative sequence alignment of OTC exon 4 sequences. A Schematic representation of the OTC pre-mRNA focused on exon 4, with exons and introns indicated by boxes and lines, and of the alternative splicing events triggered by the c.386G>A mutation in the human and mouse context. Asterisks indicate cryptic 5′ss. B Multiple sequences alignment of the OTC exon 4 5′ss and the downstream region. The human sequence has been used as reference. Dots represents conserved nucleotide. The human and mouse sequences are included within red boxes. Exon 4 and nucleotides at position +10-11 are included within green and blue boxes, respectively. The cryptic 5′ss is highlighted by the yellow box. The phylogenetic tree, together with years (millions of years, MYA) of species separation, is reported on the left. Colors indicate the type of nucleotide couple at position +10-11

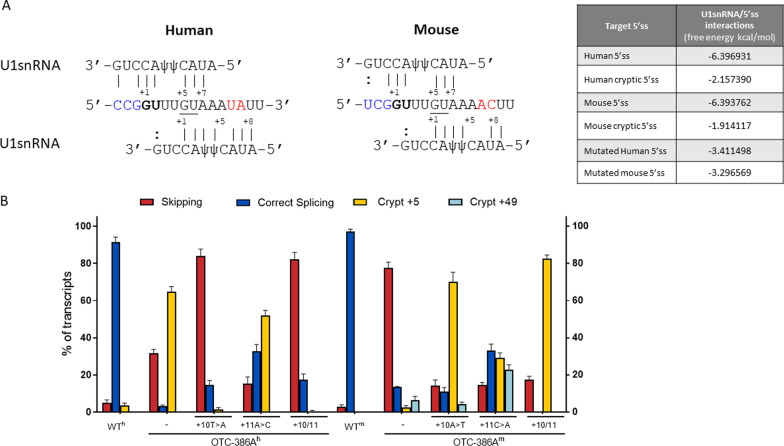

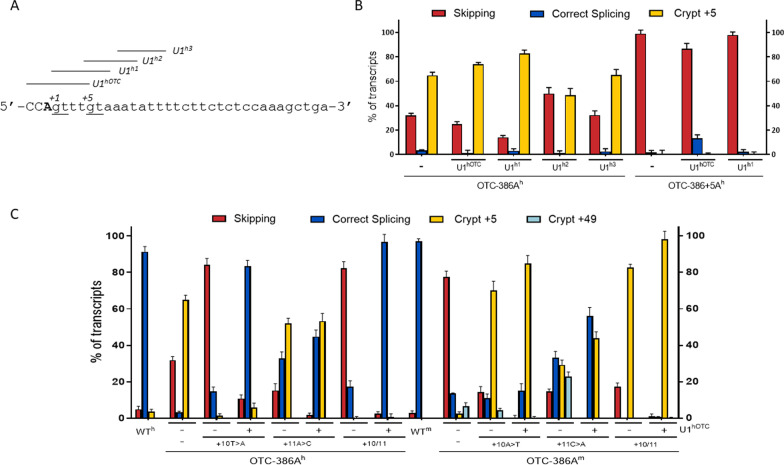

Fig. 2.

Nucleotide variations at +10-11 positions dictate species-specific splicing patterns. A Base pairing between the 5′ tail of the U1snRNA and the authentic (bold) or cryptic (underlined) 5′ss of human and mouse OTC pre-mRNA. Intronic nucleotides at position +10-11 are show in red. Continuous lines represent perfect matches while dashed line indicates partial complementarity. Nucleotides of OTC exon 4 are highlighted in blue. The minimum free energy (MFE) scores of interactions between the 5′ tail of U1snRNA and the targeted 5′ss are reported in the table on the right. B Splicing patterns of OTCh and OTCm minigenes, either wild-type (wt) or mutated, in HepG2 and Hepa1-6, respectively. Bar plots report the relative percentage of each transcript, expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments. The transcript type is indicated on the top

Intrigued by these observations, we expressed human (h) and mouse (m) OTC hybrid minigenes in human (HepG2) and mouse (Hepa1-6) hepatoma cell lines, being OTC physiologically expressed in hepatocytes. To analyze splicing patterns, we exploited construct-specific primers to avoid confounding effects of endogenous OTC mRNA, followed by denaturing capillary electrophoresis to deeply evaluate all transcript forms. The c.386G>A mutation in OTCh (OTC-386Ah) induced exon skipping (32 ± 2% of all transcripts) and usage of the proximal (c.386+5) cryptic 5′ss (65 ± 3%), with trace levels of correct transcripts (3 ± 1%) (Fig. 2B). In the OTCm (OTC-386Am), the mutation led to exon skipping (77 ± 3%), usage of the mouse-specific distal (c.386+49) cryptic 5′ss (7 ± 1%) and appreciable amount of correct transcripts (13 ± 1%). Interestingly, the capillary electrophoresis profile demonstrated for the first time the usage, albeit inefficient (2 ± 1.0%), of the proximal 5′ss even in the mouse context (Additional file 2: Fig. S1).

These data, which recapitulate and detail those previously reported, validated the experimental set-up and prompted us to define the role of +10-11 nucleotides on splicing patterns associated with the OTCD-causing mutation.

Mimicking the mouse context in the OTC-386Ah minigene by introducing the +10 T/A change abolished the usage of the cryptic 5′ss (from 65 ± 3% to 2 ± 1%, p < 0.0001) and ameliorated the usage of the authentic one (from 3 ± 1% to 14 ± 2%, p = 0.0017). Also, the +11A/C mouse-like change favored correct exon definition (33 ± 4%), and decreased the proportion of exon skipping (15 ± 4%). When these changes were combined, the OTC-386Ah minigene produced a splicing pattern that, considering the absence of the cryptic 5′ss at c.386+49 position, overlapped with that of the OTC-386Am construct (Fig. 2B).

With the same mutagenesis-based approach, we swapped +10-11 nucleotides in the OTC-386Am context. Either the human-inspired +10A/T or the +11C/A substitutions strongly favored the adjacent cryptic 5′ss (from 2 ± 1% to 70 ± 5% or 29 ± 2%, p < 0.0001, respectively) as compared to the authentic one. Accordingly, these changes in combination produced a splicing profile similar to the OTC-386Ah minigene, with virtually undetectable levels of correct transcripts.

Taken together these data indicate a key role of the +10-11 nucleotides in dictating splicing patterns triggered by the c.386G>A mutation.

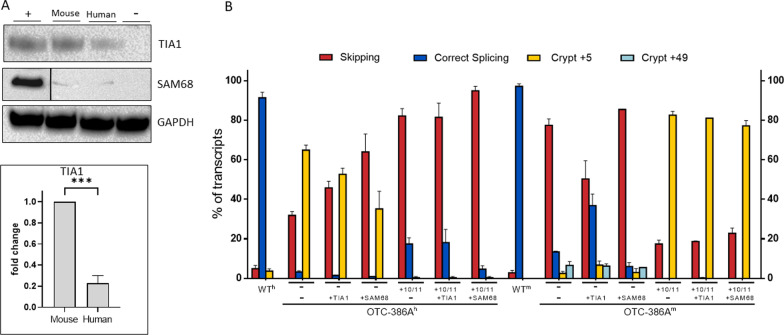

TIA1 splicing factor plays a role in governing specie-specific splicing profiles

The computational prediction of splicing factor binding sites in the exon 4 5′ss (Additional file 3: Fig. S2) suggested a preferential binding of TIA1 and Sam68 to the mouse and human sequences, respectively. Interestingly, swapping +10-11 nucleotides between human and mouse sequences resulted in an opposite prediction. To experimentally validate the bioinformatics analysis, we performed RNA oligonucleotide binding assays. Biotinylated 2-O Me RNA oligonucleotides with mouse or human sequences spanning from position +1 to +20 were incubated with HeLa cell nuclear extract and, after elution, binding of Sam68 and TIA1 analyzed by Western blotting. The results showed negligible binding of Sam68 in both human and mouse context, while TIA1 exhibited preferential binding (4.3×, p = 0.0002) for the mouse sequence compared to the human context (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

TIA1 preferentially binds nucleotide variations at +10-11 positions in mouse. A Western blot analysis of pulldown assays. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments and a representative blot is shown (NE nuclear extract input; C- naked beads). Histograms report fold changes over the wild-type. *p < 0.1; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. B Splicing patterns of OTCh and OTCm minigenes in Hepa1-6/HepG2 cells expressing minigenes variants alone or in combination with TIA1 or Sam68-expressing plasmids. Bar plots report the relative percentage of each transcript, which is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments. The transcript type is indicated on the top

To confirm the involvement of TIA1 in the specie-specific splicing pattern, we performed TIA1 and Sam68 overexpression.

Consistently, overexpression of Sam68 with mutated OTC-386A minigenes was ineffective in both contexts whereas that of TIA1 remarkably increased usage of the authentic 5′ss in the mouse context only (Fig. 3B and Additional file 4: Fig. S3).

These data indicate a functional role of the TIA1 splicing factor in the modulation of species-specific alternative splicing profiles associated with the c.386G>A mutation.

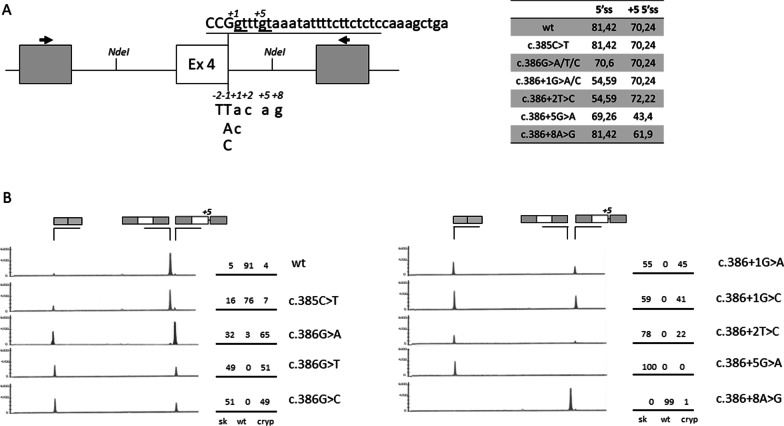

The interplay between the authentic and the cryptic 5′ss modulates the pathogenic effect of naturally-occurring OTCD-associated mutations

A panel of nucleotide changes occurring in this region (Fig. 4A), and described in OTCD patients (www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php; https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/genes/OTC), offered us the opportunity to investigate the interplay between the authentic and the cryptic 5′ss. The bioinformatic analysis of 5′ss strength predicts a differential influence of changes on the two 5′ss (Fig. 4A, right panel), with some that would affect only the authentic one (c.386G>T; c.386G>C; c.386+1G>A; c.386+1G>C; c.386+2T>C) or the cryptic (c.386+8A>G), or both (c.386+5G>A). The variable effect was demonstrated by minigene expression studies (Fig. 4B). In particular the c.385C>T mutation, at −2 position of the 5′ss, had a minor effect on splicing with a slightly decreased proportions of correct transcripts (from 91 to 76%, p = 0.0051) as compared with the wild-type OTCh construct (wth); the substitutions at positions c.386 (−1 of the 5′ss), +1 and +2 led to barely appreciable levels of correct transcripts, together with exon skipping and usage of the cryptic 5′ss; the G>A substitution at position +5, an highly represented mutation at 5′ss annotated in the human mutation database (http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php), is associated with complete exon skipping and no traces of transcript arising from the usage of the cryptic 5′ss, which was abolished by the nucleotide change; the c.386+8A>G change did not alter splicing.

Fig. 4.

The interplay between the authentic and the cryptic 5′ss governs the pathogenic effect of natural OTC mutations. A Schematic representation of the human OTC exon 4 genomic sequence cloned as minigene in the pTB vector within the NdeI sites. Exonic and intronic sequences are represented by boxes and lines, respectively. Primers (arrows) used to perform the RT-PCR are indicated on top. The sequences, with exonic and intronic nucleotides in upper and lower cases respectively, report (i) the authentic 5′ss with the positions of the investigated changes detailed below, and (ii) the cryptic 5′ss. Both 5′ss are underlined. The table reports the scores of the 5′ss in the normal sequence and in the presence of different OTC nucleotide changes found in OTCD patients. B OTCh splicing patterns evaluated by RT-PCR and denaturing capillary electrophoresis on RNA isolated from HepG2 transiently transfected with the wild-type (wt) minigene or harboring the indicated nucleotide changes. The schematic representation of transcripts (with exons not in scale) is reported on top. Numbers on the right report the relative percentage of each transcript type

Overall, these data define the molecular bases of OTCD-causing mutations at the 5′ss of OTC exon 4 and provide evidence for the interplay between the authentic and the cryptic 5′ss in governing the pathogenic splicing mechanisms.

The nucleotide context of human and mouse OTC exon 4 accounts for a differential susceptibility to RNA-based correction by engineered U1snRNA

Based on our previous in vitro and in vivo finding that engineered U1snRNA, either compensatory or exon specific (ExSpe) variants, efficiently rescue splicing of OTC exon 4 in the mouse context (Balestra et al. 2020a), we expressed a panel of U1snRNA variants (Fig. 5A) designed on the human OTC context. In co-transfection experiments none of the engineered U1snRNAs appreciably improved selection of the authentic mutated 5′ss in the presence of the c.386G>A mutation but, while decreasing exon skipping, further promoted usage of the adjacent cryptic 5′ss.

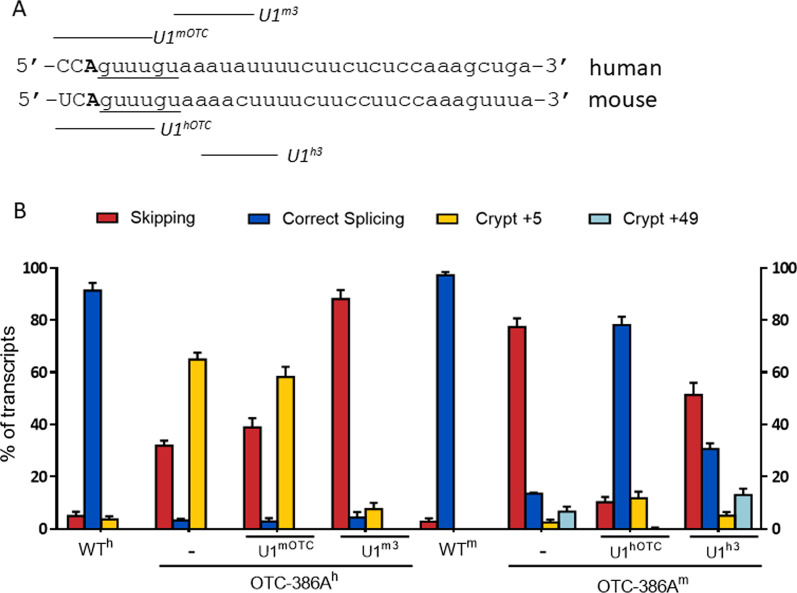

Fig. 5.

The strong cryptic 5′ss prevents U1snRNA-mediated correction in the human context. A Genomic sequence of the human OTC exon 4 exon–intron junction, with exonic and intronic nucleotides in upper and lower cases, respectively. The c.386G>A change is indicated in bold. The regions targeted by modified U1h of the corresponding pre-mRNA are reported on top. B Splicing patterns in HepG2 transiently transfected with OTCh-386A or OTCh-386+5a minigenes alone or in combination with engineered U1h, and expressed as bar plots indicating the relative percentage of each transcript. Results are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. C Splicing pattern in HepG2 or Hepa1-6 cells transiently transfected with human and mouse OTC minigenes differing at +10-11 positions alone or in combination with the corresponding U1hOTC designed on the mutated 5′ss. Bar plots indicate the relative percentage of each transcript and results are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments

The interference of the cryptic 5′ss with the usage of the authentic one was tested by challenging the natural OTC-386+5G>A mutant lacking the cryptic 5′ss. Here, the compensatory U1hOTC appreciably increased the proportion of correct transcripts (from 2 ± 1% to 13 ± 3%, p = 0.0032) (Fig. 5B and Additional file 5: Fig. S4).

Intrigued by the observation on the role of nucleotides at position +10-11 in dictating the preference for the two neighboring 5′ss in the human background, we evaluated the U1snRNA efficacy in the previously created mouse-like OTC-386Ah variants. As observed in Fig. 5C and Additional file 6: Fig. S5, changes at nucleotides +10 and +11, either singularly or in combination, rendered the OTC-386Ah rescuable by the U1hOTC. Vice versa, the introduction of the human nucleotides at positions +10-11 in the OTC-386Am prevented the U1snRNA-mediated correction.

Due to the high homology between the human and mouse OTC exon 4, we also challenged the modified U1snRNAs designed on OTC-386Ah towards the OTC-386Am, and vice versa (Fig. 6A). In co-transfection assays, the human-tailored U1hOTC appreciably rescued the OTC-386Am to an extent comparable to that obtained with the mouse-tailored U1mOTC and U1m3. On the other hand, the mouse-tailored U1snRNAs failed to correct splicing in the OTC-386Ah context (Fig. 6B and Additional file 7: Fig. S6).

Fig. 6.

Cross-activity of the human and mouse tailored U1snRNAs. A Pre-mRNA sequences of the human and mouse OTC exon 4 exon–intron junctions, with exonic and intronic nucleotides in upper and lower cases, respectively. The regions targeted by the 5′ tail of the modified U1snRNAs are reported (solid line). The c.386G>A change is indicated in bold. B The bar plots report the splicing patterns in HepG2 or Hepa1-6 transiently transfected with the OTC-386Ah (left) or OTC-386Am (right) minigenes, respectively, and challenged with the U1 variants. Bar plots indicate the relative percentage of each transcript, and results are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments

Overall data demonstrated that the strong proximal cryptic 5′ss in the human OTC context prevents U1snRNA-mediated correction of the c.386G>A mutation.

Discussion

The mouse is the most commonly used animal to model human disease. However, despite the striking genetic homology with human genome that makes studying mice so insightful to understand human diseases, numerous studies showed discrepancies between the human and mouse phenotypes in pathological condition (Elsea and Lucas 2002; Bochner et al. 2013; Telias 2019; Brown et al. 2020).

Aberrant splicing is a common outcome in the presence of exonic or intronic variants that might hamper the intricate network of interactions defining an exon in a specific gene context. Therefore, the evaluation of the functional, and potentially pathological, role of nucleotide changes remains one of the major challenges in the modern genomic era (Taneri et al. 2012; Hartin et al. 2020). This aspect has also to be taken into account during the pre-clinical evaluation of innovative therapeutic approaches in animal models of human diseases. This is of particular relevance when developing therapeutics acting on splicing, an intriguing and expanding research area for several disorders (Donadon et al. 2018, 2019; Yamazaki et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2019; Donegà et al. 2020).

Ornithine TransCarbamylase Deficiency (OTCD) is the most frequent urea cycle disease, an X-linked recessive trait caused by mutations in OTC gene, which is expressed in liver and encodes a mitochondrial enzyme. There is no cure for OTCD but only treatments to limit hyperammonemia, and the disease features make a strong quest for alternative therapies. Among the OTCD mouse models, the mouse spfash is characterized by the c.386G>A splicing mutation and it has been exploited to evaluate replacement gene therapy approaches (Moscioni et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2011, 2012; Cunningham et al. 2013). This animal model represents therefore an ideal pre-clinical platform to assess the therapeutic potential of RNA therapeutics based on engineered variants of the spliceosomal U1snRNAs, which were proven to be capable, both in cellular (Glaus et al. 2011; Schmid et al. 2013; Scalet et al. 2017, 2018, 2019; Martínez-Pizarro et al. 2018; Balestra et al. 2019a, b; Martín et al. 2021) and animal (Balestra et al. 2014, 2016, 2020b; Dal Mas et al. 2015; Rogalska et al. 2016) models of human diseases, to counteract splicing mutations and force exon recognition, thus rescuing gene expression. Recently, a U1snRNA variant, upon delivery via an Adeno-Associated virus Vector in spfash mice, partially restored OTC expression at RNA and protein level in liver (Balestra et al. 2020a). On the other hand, translation to humans requires careful evaluation of splicing regulatory elements accounting for species-specific splicing profiles, and potentially affecting responsiveness to splicing-switching molecules.

As a matter of fact, the OTCD-causing c.386G>A mutation leads to different splicing patterns in the human and mouse contexts. By combining computational analysis and minigene assays we demonstrated that, with the exception of the cryptic 5′ss at position +49 of intron 4, which is a peculiar feature of the mouse genomic context, variations at intronic +10-11 positions modulate the interplay between the authentic and the adjacent (+5) cryptic 5′ss, and explain the differential species-specific impact of the c.386G>A mutation, and the milder effects in the mouse context. Pull-down and over-expression assays revealed that the TIA1 splicing factor preferentially binds at positions +10-11 in the mouse context, and has a functional role. As previously reported (Förch et al. 2002; Gal-Mark et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2014), TIA1 can favor the recruitment of U1snRNP at the 5′ss through the interaction with the U1snRNP subunits U1C. Therefore, interaction of the endogenous U1snRNP with the splicing factor TIA1, bound in the proximity of the 5′ss of OTC exon 4, would explain the species-specific splicing outcome observed in the spfash mouse model, leading to a better exon definition and thus selection of the authentic but mutated 5′ss. Conversely, the prevalent usage of the adjacent cryptic 5′ss in humans seems the results of the poor interaction with TIA1, disfavoring recognition of the authentic 5′ss by the U1snRNA in the presence of the mutation. In fact, it is well reported that U1snRNA interact with the 5′ss through base-pairing with nucleotides from −3 to +6 positions with reference to the exon–intron junction, extending also up to +7-8 positions (Tan et al. 2016).

These species-specific elements also explained the inability of engineered U1snRNA, either complementary or exon-specific, to re-direct usage of the authentic, albeit mutated, 5′ss in the human context, a correction effect that was restored with the incorporation of the mouse nucleotides at positions +10-11. It is worth noting that the compensatory human-tailored U1hOTC appreciably rescued the OTC-386Am thus ruling out that their ineffectiveness on hOTC was due to inefficient incorporation of the U1snRNA into a functional U1snRNP within cells or to reach the target. Taken together these data demonstrated that, in the hOTC context, the strong proximal cryptic 5′ss and the lack of binding of the splicing factor TIA1 helping correct 5′ss definition prevents U1snRNA-mediated correction of the c.386G>A mutation.

On the other hand, the interplay between the authentic and the proximal cryptic 5′ss in hOTC dictates the alternative splicing profile triggered by nucleotide changes occurring in this region and associated with OTCD in patients, and provide insights into their pathogenic role. In particular, the c.385C>T change, occurring at position −2 of the 5′ss, had a minor effect on splicing, a finding that points toward a major pathogenic role of the corresponding amino acid change (p.R129C) on OTC protein. The c.386+8A>G change did not alter splicing, thus leading to classify it as a silent polymorphism. Variants at positions −1 (c.386G>A, c.386G>T, and c.386G>C), +1 (c.386+1G>A, c.386+1G>C) and +2 (c.386+2T>C) led to barely appreciable levels of correct transcripts. Although studies in mice reported that the p.R129H amino acid change does not impair OTC activity (Hodges and Rosenberg 1989), and not excluding a contribution of the underlying p.R129L and p.R129P amino acid changes on OTC protein, these data indicate that these mutations exert their main pathogenic role via splicing impairment. Finally, the c.386+5G>A variant, a highly represented mutation at 5′ss annotated in the human mutation database (http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php), leads to complete exon skipping. Noticeably, this mutation, by abrogating the cryptic 5′ss, was rescued by the U1hOTC variant, thus further strengthening a mechanism where competition between 5′ss is governed by a downstream splicing regulatory element.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we dissected the molecular mechanisms underlying species-specific splicing profiles triggered by the c.386G>A mutation, relatively frequent in humans, and its responsiveness to U1snRNA-mediated correction, and provided the rationale to humanize the spfash and mimic the OTCD molecular phenotype. Subtle changes accounting for differential binding of splicing factors such as TIA1 at positions +10-11 govern the competition between alternative 5′ss, which in turn can be modulated by naturally-occurring mutations. Data refined the classification and pathogenic mechanisms of human OTC mutations, which assist genetic counselling, and highlight the importance to carefully investigate specie-specific molecular mechanisms for translational purposes.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Oligonucleotides for creation of minigenes and analysis of splicing. Table S2. Oligonucleotides for creation of engineered U1snRNA.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. The sequence at intronic positions +10 and +11 explains species-specific splicing patterns. A Evaluation by capillary electrophoresis of OTC splicing patterns in HepG2 and Hepa1-6 cells transiently transfected with human and mouse minigenes. The schematic representation of the transcripts is reported on top. B The electropherogram reports the sequence of the aberrant transcripts arising from the usage of the alternative 5′ss at position +5. Exon 4 is indicated by the white box.

Additional file 3: Figure S2. Bioinformatic analysis of splicing factors show TIA1 preferential binding at nucleotide variations +10-11 in mouse. Bioinformatic analysis of splicing factors binding at mouse (upper) and human (lower) 5′ss of exon 4. Exonic and intronic sequences are indicated in upper and lower case, respectively. Bar plots report the positive and negative scores of target sequences that facilitate exon and intron definition, respectively. Bars have variable width and height respectively related to the number of nucleotides of the binding site and to its score (binding affinity). The label over each bar indicates the name of the protein predicted to bind moreover overlapping bars.

Additional file 4: Figure S3. Overexpression of TIA1, but Sam68, remarkably increased usage of the authentic 5′ss in the mouse context. Evaluation by capillary electrophoresis of OTC splicing patterns in HepG2 and Hepa1-6 cells transiently transfected with the human or mouse minigenes alone or in combination with TIA1 or Sam68-expressing plasmids. The schematic representation of the transcripts is reported on top.

Additional file 5: Figure S4. The compensatory U1hOTC, but not the ExSpe U1h1, partially rescue the natural c.386+5G>A mutation. Evaluation by capillary electrophoresis of OTC splicing patterns in HepG2 cells transiently transfected with the human minigenes, harboring the c.386G>A or c.386+5G>A variants, alone or in combination with engineered U1snRNA variants, either the complementary (U1hOTC) and Exon Specific (U1h1, U1h2, U1h3) ones. The schematic representation of the transcripts is reported on top.

Additional file 6: Figure S5. Nucleotides +10 and +11, either singularly or in combination, renders the human c.386G>A variant rescuable by the compensatory U1hOTC. Evaluation by capillary electrophoresis of OTC splicing patterns in HepG2 or Hepa1-6 cells transiently transfected with human and mouse OTC minigenes differing at +10-11 positions alone or in combination with the corresponding U1hOTC designed on the mutated 5′ss. The schematic representation of the transcripts is reported on top.

Additional file 7: Figure S6. Cross-activity of the human and mouse tailored U1snRNAs. Evaluation by capillary electrophoresis of OTC splicing patterns in HepG2 or Hepa1-6 cells transiently transfected with the OTC-386Ah (left) or OTC-386Am (right) minigenes, respectively, and challenged with the U1 variants. The schematic representation of the transcripts is reported on top.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- 5′ss

5′ Donor splice site

- AS

Alternative splicing

- ExSpeU1

Exon specific U1snRNA

- OTC

Ornithine TransCarbamylase

- OTCD

Ornithine TransCarbamylase Deficiency

- ss

Splice site

- U1snRNA

U1 small nuclear RNA

- U1snRNP

Spliceosomal U1 ribonucleoprotein

Authors' contributions

LP created human OTC expression vectors and tested the role of the +10-11 nucleotides on splicing patterns, drafted the paper and compiled the figures; CS designed the U1snRNA variants and tested them in the mouse and human context; IM performed denaturing capillary electrophoresis; FT performed comparative OTC analysis; FB, FB, FP, SFJvdG analyzed and interpreted data and revised the manuscript. DB and MP conceived the study, designed the experiments, drafted the paper and compiled the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by AFM Telethon (#21527) and the University of Ferrara. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

M.P. and F.P. are inventors of patents on modified U1snRNAs. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Claudia Sacchetto, Laura Peretto, Mirko Pinotti and Dario Balestra have contributed equally to the study

Contributor Information

Mirko Pinotti, Email: pnm@unife.it.

Dario Balestra, Email: blsdra@unife.it.

References

- Balestra D, Faella A, Margaritis P, Cavallari N, Pagani F, Bernardi F, et al. An engineered U1 small nuclear RNA rescues splicing-defective coagulation F7 gene expression in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(2):177–185. doi: 10.1111/jth.12471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestra D, Barbon E, Scalet D, Cavallari N, Perrone D, Zanibellato S, et al. Regulation of a strong F9 cryptic 5′ss by intrinsic elements and by combination of tailored U1snRNAs with antisense oligonucleotides. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(17):4809–4816. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestra D, Scalet D, Pagani F, Rogalska ME, Mari R, Bernardi F, et al. An exon-specific U1snRNA induces a robust factor IX activity in mice expressing multiple human FIX splicing mutants. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2016;5(10):e370. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2016.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestra D, Giorgio D, Bizzotto M, Fazzari M, Ben Zeev B, Pinotti M, et al. Splicing mutations impairing CDKL5 expression and activity can be efficiently rescued by U1snRNA-based therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(17):4130. doi: 10.3390/ijms20174130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestra D, Maestri I, Branchini A, Ferrarese M, Bernardi F, Pinotti M. An altered splicing registry explains the differential ExSpeU1-mediated rescue of splicing mutations causing haemophilia A. Front Genet. 2019;10:974. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestra D, Ferrarese M, Lombardi S, Ziliotto N, Branchini A, Petersen N, et al. An exon-specific small nuclear U1 RNA (ExSpeU1) improves hepatic OTC expression in a splicing-defective spf/ash mouse model of ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(22):8735. doi: 10.3390/ijms21228735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestra D, Scalet D, Ferrarese M, Lombardi S, Ziliotto N, Croes CC, et al. A compensatory U1snRNA partially rescues FAH splicing and protein expression in a splicing-defective mouse model of tyrosinemia type I. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(6):2136. doi: 10.3390/ijms21062136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baralle M, Baralle FE. The splicing code. Biosystems. 2018;164:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa-Morais NL, Irimia M, Pan Q, Xiong HY, Gueroussov S, Lee LJ, et al. The evolutionary landscape of alternative splicing in vertebrate species. Science. 2012;338(6114):1587–1593. doi: 10.1126/science.1230612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochner R, Ziv Y, Zeevi D, Donyo M, Abraham L, Ashery-Padan R, et al. Phosphatidylserine increases IKBKAP levels in a humanized knock-in IKBKAP mouse model. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(14):2785–2794. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SC, Fernandez-Fuente M, Muntoni F, Vissing J. Phenotypic spectrum of α-dystroglycanopathies associated with the c.919T>a variant in the FKRP gene in humans and mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2020;79(12):1257–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cunningham SC, Kok CY, Spinoulas A, Carpenter KH, Alexander IE. AAV-encoded OTC activity persisting to adulthood following delivery to newborn spfash mice is insufficient to prevent shRNA-induced hyperammonaemia. Gene Ther. 2013;20(12):1184–1187. doi: 10.1038/gt.2013.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Mas A, Rogalska ME, Bussani E, Pagani F. Improvement of SMN2 pre-mRNA processing mediated by exon-specific U1 small nuclear RNA. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(1):93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Conti L, Baralle M, Buratti E. Exon and intron definition in pre-mRNA splicing. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2013;4(1):49–60. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donadon I, Pinotti M, Rajkowska K, Pianigiani G, Barbon E, Morini E, et al. Exon-specific U1 snRNAs improve ELP1 exon 20 definition and rescue ELP1 protein expression in a familial dysautonomia mouse model. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27(14):2466–2476. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donadon I, Bussani E, Riccardi F, Licastro D, Romano G, Pianigiani G, et al. Rescue of spinal muscular atrophy mouse models with AAV9-exon-specific U1 snRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(14):7618–7632. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donegà S, Rogalska ME, Pianigiani G, Igreja S, Amaral MD, Pagani F. Rescue of common exon-skipping mutations in cystic fibrosis with modified U1 snRNAs. Hum Mutat. 2020;41(12):2143–2154. doi: 10.1002/humu.24116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsea SH, Lucas RE. The mousetrap: what we can learn when the mouse model does not mimic the human disease. ILAR J. 2002;43(2):66–79. doi: 10.1093/ilar.43.2.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraresi P, Balestra D, Guittard C, Buthiau D, Pan-Petesh B, Maestri I, et al. Next-generation sequencing and recombinant expression characterized aberrant splicing mechanisms and provided correction strategies in factor VII deficiency. Haematologica. 2020;105(3):829–37. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.217539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förch P, Puig O, Martínez C, Séraphin B, Valcárcel J. The splicing regulator TIA-1 interacts with U1-C to promote U1 snRNP recruitment to 5′ splice sites. EMBO J. 2002;21(24):6882–6892. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal-Mark N, Schwartz S, Ram O, Eyras E, Ast G. The pivotal roles of TIA proteins in 5′ splice-site selection of Alu exons and across evolution. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(11):e1000717. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaus E, Schmid F, Da Costa R, Berger W, Neidhardt J. Gene therapeutic approach using mutation-adapted U1 snRNA to correct a RPGR Splice defect in patient-derived cells. Mol Ther. 2011;19(5):936–941. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartin SN, Means JC, Alaimo JT, Younger ST. Expediting rare disease diagnosis: a call to bridge the gap between clinical and functional genomics. Mol Med. 2020;26(1):117. doi: 10.1186/s10020-020-00244-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges PE, Rosenberg LE. The spf(ash) mouse: a missense mutation in the ornithine transcarbamylase gene also causes aberrant mRNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86(11):4142–4146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Magen A, Ast G. Different levels of alternative splicing among eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(1):125–131. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Kim Y, Kim S, Goh S, Kim J, Oh S, et al. Modified U1 snRNA and antisense oligonucleotides rescue splice mutations in SLC26A4 that cause hereditary hearing loss. Hum Mutat. 2019 doi: 10.1002/humu.23774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín E, Vivori C, Rogalska M, Herrero-Vicente J, Valcárcel J. Alternative splicing regulation of cell-cycle genes by SPF45/SR140/CHERP complex controls cell proliferation. RNA. 2021;27(12):1557–1576. doi: 10.1261/rna.078935.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Pizarro A, Dembic M, Pérez B, Andresen BS, Desviat LR. Intronic PAH gene mutations cause a splicing defect by a novel mechanism involving U1snRNP binding downstream of the 5′ splice site. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(4):1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkin J, Russell C, Chen P, Burge CB. Evolutionary dynamics of gene and isoform regulation in mammalian tissues. Science. 2012;338(6114):1593–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.1228186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscioni D, Morizono H, McCarter RJ, Stern A, Cabrera-Luque J, Hoang A, et al. Long-term correction of ammonia metabolism and prolonged survival in ornithine transcarbamylase-deficient mice following liver-directed treatment with adeno-associated viral vectors. Mol Ther. 2006;14(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen TW, Graveley BR. Expansion of the eukaryotic proteome by alternative splicing. Nature. 2010;463(7280):457–463. doi: 10.1038/nature08909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Barahona A, Sánchez-Alcudia R, Viecelli HM, Rüfenacht V, Pérez B, Ugarte M, et al. Functional characterization of the spf/ash splicing variation in OTC deficiency of mice and man. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0122966–e0122966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogalska ME, Tajnik M, Licastro D, Bussani E, Camparini L, Mattioli C, et al. Therapeutic activity of modified U1 core spliceosomal particles. Nat Commun. 2016;7(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalet D, Balestra D, Rohban S, Bovolenta M, Perrone D, Bernardi F, et al. Exploring splicing-switching molecules for Seckel syndrome therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1863(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalet D, Sacchetto C, Bernardi F, Pinotti M, Van De Graaf SFJ, Balestra D. The somatic FAH C.1061C>A change counteracts the frequent FAH c.1062+5G>A mutation and permits U1snRNA-based splicing correction. J Hum Genet. 2018;63(5):683–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Scalet D, Maestri I, Branchini A, Bernardi F, Pinotti M, Balestra D. Disease-causing variants of the conserved +2T of 5′ splice sites can be rescued by engineered U1snRNAs. Hum Mutat. 2019;40(1):48–52. doi: 10.1002/humu.23680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid F, Hiller T, Korner G, Glaus E, Berger W, Neidhardt J. A gene therapeutic approach to correct splice defects with modified U1 and U6 snRNPs. Hum Gene Ther. 2013;24(1):97–104. doi: 10.1089/hum.2012.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Ho JXJ, Zhong Z, Luo S, Chen G, Roca X. Noncanonical registers and base pairs in human 5′ splice-site selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(8):3908–3921. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneri B, Asilmaz E, Gaasterland T. Biomedical impact of splicing mutations revealed through exome sequencing. Mol Med. 2012;18(2):314–319. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telias M. Fragile X syndrome pre-clinical research: comparing mouse- and human-based models. Methods Mol Biol Clifton NJ. 2019;1942:155–162. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9080-1_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuchman M, Jaleel N, Morizono H, Sheehy L, Lynch MG. Mutations and polymorphisms in the human ornithine transcarbamylase gene. Hum Mutat. 2002;19(2):93–107. doi: 10.1002/humu.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Wang H, Morizono H, Bell P, Jones D, Lin J, et al. Sustained correction of OTC deficiency in spfash mice using optimized self-complementary AAV2/8 vectors. Gene Ther. 2011;19(4):404–410. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Morizono H, Lin J, Bell P, Jones D, McMenamin D, et al. Preclinical evaluation of a clinical candidate AAV8 vector for ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency reveals functional enzyme from each persisting vector genome. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;105(2):203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang I, Hennig J, Jagtap PKA, Sonntag M, Valcárcel J, Sattler M. Structure, dynamics and RNA binding of the multi-domain splicing factor TIA-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(9):5949–5966. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S, Brailey LL, Morizono H, Bale AE, Tuchman M. Mutations and polymorphisms in the human ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) gene. Hum Mutat. 2006;27(7):626–632. doi: 10.1002/humu.20339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki N, Kanazawa K, Kimura M, Ike H, Shinomiya M, Tanaka S, et al. Use of modified U1 small nuclear RNA for rescue from exon 7 skipping caused by 5′-splice site mutation of human cathepsin A gene. Gene. 2018;677:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer KP, Bendiks M, Mori M, Kominami E, Robinson MB, Ye X, et al. Efficient mitochondrial import of newly synthesized ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) and correction of secondary metabolic alterations in spfash mice following gene therapy of OTC deficiency. Mol Med. 1999;5(4):244–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Oligonucleotides for creation of minigenes and analysis of splicing. Table S2. Oligonucleotides for creation of engineered U1snRNA.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. The sequence at intronic positions +10 and +11 explains species-specific splicing patterns. A Evaluation by capillary electrophoresis of OTC splicing patterns in HepG2 and Hepa1-6 cells transiently transfected with human and mouse minigenes. The schematic representation of the transcripts is reported on top. B The electropherogram reports the sequence of the aberrant transcripts arising from the usage of the alternative 5′ss at position +5. Exon 4 is indicated by the white box.

Additional file 3: Figure S2. Bioinformatic analysis of splicing factors show TIA1 preferential binding at nucleotide variations +10-11 in mouse. Bioinformatic analysis of splicing factors binding at mouse (upper) and human (lower) 5′ss of exon 4. Exonic and intronic sequences are indicated in upper and lower case, respectively. Bar plots report the positive and negative scores of target sequences that facilitate exon and intron definition, respectively. Bars have variable width and height respectively related to the number of nucleotides of the binding site and to its score (binding affinity). The label over each bar indicates the name of the protein predicted to bind moreover overlapping bars.

Additional file 4: Figure S3. Overexpression of TIA1, but Sam68, remarkably increased usage of the authentic 5′ss in the mouse context. Evaluation by capillary electrophoresis of OTC splicing patterns in HepG2 and Hepa1-6 cells transiently transfected with the human or mouse minigenes alone or in combination with TIA1 or Sam68-expressing plasmids. The schematic representation of the transcripts is reported on top.

Additional file 5: Figure S4. The compensatory U1hOTC, but not the ExSpe U1h1, partially rescue the natural c.386+5G>A mutation. Evaluation by capillary electrophoresis of OTC splicing patterns in HepG2 cells transiently transfected with the human minigenes, harboring the c.386G>A or c.386+5G>A variants, alone or in combination with engineered U1snRNA variants, either the complementary (U1hOTC) and Exon Specific (U1h1, U1h2, U1h3) ones. The schematic representation of the transcripts is reported on top.

Additional file 6: Figure S5. Nucleotides +10 and +11, either singularly or in combination, renders the human c.386G>A variant rescuable by the compensatory U1hOTC. Evaluation by capillary electrophoresis of OTC splicing patterns in HepG2 or Hepa1-6 cells transiently transfected with human and mouse OTC minigenes differing at +10-11 positions alone or in combination with the corresponding U1hOTC designed on the mutated 5′ss. The schematic representation of the transcripts is reported on top.

Additional file 7: Figure S6. Cross-activity of the human and mouse tailored U1snRNAs. Evaluation by capillary electrophoresis of OTC splicing patterns in HepG2 or Hepa1-6 cells transiently transfected with the OTC-386Ah (left) or OTC-386Am (right) minigenes, respectively, and challenged with the U1 variants. The schematic representation of the transcripts is reported on top.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.