Abstract

We report a subtype of immune‐mediated encephalitis associated with COVID‐19, which closely mimics acute‐onset sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. A 64‐year‐old man presented with confusion, aphasia, myoclonus, and a silent interstitial pneumonia. He tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2. Cognition and myoclonus rapidly deteriorated, EEG evolved to generalized periodic discharges and brain MRI showed multiple cortical DWI hyperintensities. CSF analysis was normal, except for a positive 14‐3‐3 protein. RT‐QuIC analysis was negative. High levels of pro‐inflammatory cytokines were present in the CSF and serum. Treatment with steroids and intravenous immunoglobulins produced EEG and clinical improvement, with a good neurological outcome at a 6‐month follow‐up.

Introduction

At the time of this writing, health care systems are facing worldwide the coronavirus SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic and its associated disease, named COVID‐19. A variety of central nervous system (CNS) manifestations has been associated with COVID‐19, ranging from mild encephalopathy to necrotizing encephalitis, 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 despite CNS damage directly caused by SARS‐CoV‐2 seems unlikely from neuropathological studies. 5 , 6 Here, we report the case of an immune‐mediated encephalitis, with several features (EEG, MRI, CSF) mimicking acute‐onset sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (sCJD), occurring in the late hase of an asymptomatic COVID‐19 infection.

Case Presentation

A 64‐year‐old man was admitted to the Emergency Department with confusion, disorientation, moderate aphasia, mild right hemiparesis, and irregular myoclonic jerks at the right limbs, with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) 12 (eyes opening to verbal command, confused, localizing pain, not obeying commands). His wife reported that she saw him normal 3 hours earlier. He neither had fever nor respiratory symptoms in the previous days. His past medical history included hypothyroidism and hypertension. Brain CT and CT‐angiography were negative. Chest CT scan showed bilateral interstitial pneumonia, while his arterial blood oxygen was normal. D‐dimer levels (387 ng/mL) and C‐reactive protein (7.92 mg/dL) were mildly elevated. Nasopharyngeal swab and bronchoalveolar lavage tested negative for SARS‐CoV‐2 on admission, but repeated SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR on both respiratory tract specimens resulted positive on day 7, when anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies to nucleocapsid antigen were also found elevated in serum. A diagnosis of late‐phase, asymptomatic COVID‐19 pneumonia was made.

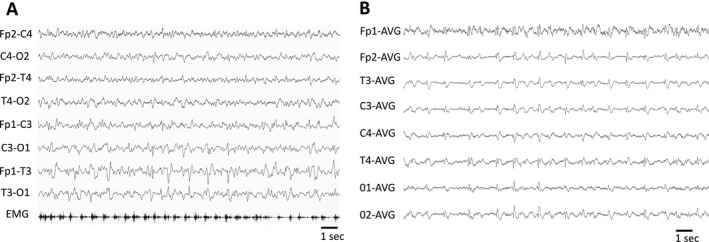

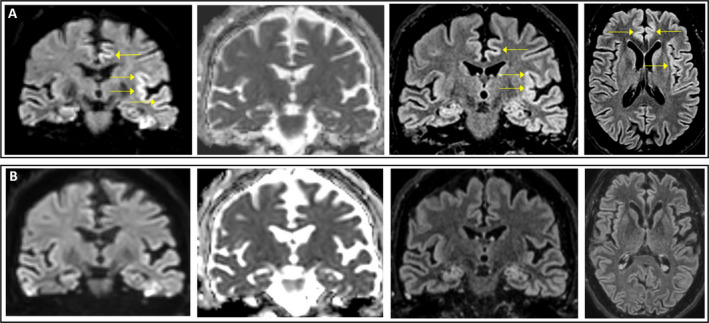

A first EEG showed irregular, left‐sided periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges (Figure 1A), apparently time‐locked with right‐sided myoclonus (back averaging analysis was not performed). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed normal protein content (18 mg/dL) and cell count (3 cells/uL); comprehensive virologic testing (including HSV1, HSV2, VZV, EBV, CMV, HHV6, HHV8, adenovirus, enterovirus, parvovirus B19, JC virus, West Nile virus, influenza A and B virus, respiratory syncytial virus A and B, Zika virus, and SARS‐CoV‐2) was negative, as well as bacterial and fungal cultures. Oligoclonal bands were present in both CSF and serum (pattern type 4). Onconeural antibodies (GAD‐65, Zic4, Tr, SOX1, Ma2, Ma1, amphiphysin, CRMP5, Hu, Yo, Ri), GAD‐65, and neural surface antigens antibodies (VGKC, LGI1, CASPR2, DPPX, NMDAr, AMPA1‐2, mGluR3, GABAb1, VGCC) were absent in serum and CSF. We also tested serum and CSF using a tissue‐based assay on primate brain sections, without obtaining any specific fluorescence signal. He was initially treated with intravenous diazepam followed by intravenous antiepileptic drugs (valproate, levetiracetam, lacosamide), without clinical benefit. The day after admission, the level of consciousness decreased to GCS 7 (no eyes opening, no verbal response, localizing pain on the left, no motor response on the right) and acute respiratory failure developed, requiring intubation and transfer to the Intensive Care Unit. Continuous EEG monitoring showed evolution of the EEG pattern to generalized periodic epileptiform discharges at 1 Hz (Figure 1B), which were transiently abolished during two cycles of anesthetics (propofol‐midazolam for 24 hours and ketamine‐midazolam for 48 hours), but relapsed after withdrawal of anesthetics. Add‐on perampanel had no effect on either EEG or clinical picture. On day 3, a first brain MRI was normal. Seven days later (on day 10) a second brain MRI showed signal hyperintensity of the cortical ribbon of the left perisylvian regions (insula, middle frontal gyrus, inferior parietal lobule, and superior temporal gyrus) and bilateral cingulate gyrus on diffusion‐weighted imaging (DWI) sequences, without concomitant reduction on the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map and with subtle hyperintensities on fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences (Figure 2A).

Figure 1.

Representative EEG epochs showing left‐sided lateralized periodic discharges with associated myoclonus on day 1 (A) and generalized periodic discharges on day 7 (B). EMG = right flexor carpi surface electromyography electrode.

Figure 2.

Representative MRI images showing coronal DWI, ADC, and FLAIR sequences of the same slice and axial FLAIR sequence, performed in the subacute phase (day 10; (A) and post‐acute phase (day 50; (B). Abnormal cortical areas are indicated by arrows. Notably, ADC map does not show commensurate hypointensity in the anterior cingulate and insula, where the DWI and FLAIR cortical hyperintensity was present. ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DWI, diffusion‐weighted imaging; FLAIR, fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery.

Considering MRI evolution, EEG showing periodic sharp wave complexes and refractoriness to treatment, a differential diagnosis between acute‐onset sCJD and autoimmune encephalitis associated with COVID‐19 was hypothesized.

Further diagnostic tests were performed on the CSF and serum samples: 14‐3‐3 protein was positive on a CSF sample from day 10; nonetheless, Real Time Quaking‐Induced Conversion (RT‐QuIC) analysis did not show any positive seeding activity due the presence of prion; re‐assessment of the CSF and serum samples from day 1 showed very high levels of IL‐6 in the CSF, compared to serum, elevated levels of IL‐23 and IL‐31 in both serum and CSF and elevated IL‐33 in serum (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected values of laboratory diagnostic tests on cerebrospinal fluid and serum.

| Diagnostic test | Day | Unit | CSF [normal range] | Serum [normal range] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins | 1 | mg/dL | 18 [15‐45] | ‐ |

| Glucose | 1 | mg/dL | 63 [40‐70] | 110 [70‐110] |

| White cell count | 1 | cells | 3 [< 4] | ‐ |

| Link index | 1 | ratio | 0.63 [0.10‐0.70] | ‐ |

| Oligoclonal bands | 1 | ‐ | Present (pattern 4) | Present (pattern 4) |

| Gram stain | 1 | ‐ | Negative | ‐ |

| SARS‐CoV‐2 | 1 | ‐ | Negative | ‐ |

| Anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 IgG | 7 | ‐ | ‐ | Positive |

| 14‐3‐3 protein | 10 | ‐ | Positive | ‐ |

| RT‐QuIC assay | 10 | ‐ | Negative | ‐ |

| IL‐1beta | 1 | pg/mL | 0.68 | 1.70 [<5.8] |

| IL‐4 | 1 | pg/mL | 0 | 9.21 [4.06‐5.5] |

| IL‐6 | 1 | pg/mL | 299.89 | 20.14 [<24.8] |

| IL‐10 | 1 | pg/mL | 1.48 | 6.82 [0.6‐25.0] |

| IL‐17a | 1 | pg/mL | 1.59 | 8.68 [<9.7] |

| IL‐17f | 1 | pg/mL | 0 | 8.68 [absent] |

| IL‐21 | 1 | pg/mL | 0 | 34.23 [absent] |

| IL‐22 | 1 | pg/mL | 2.87 | 15.40 [absent] |

| IL‐23 | 1 | pg/mL | 81.24 | 333.52 [absent] |

| IL‐25 | 1 | pg/mL | 0.55 | 3.54 [absent] |

| IL‐31 | 1 | pg/mL | 20.23 | 424.51 [absent] |

| IL‐33 | 1 | pg/mL | 0 | 98.43 [absent] |

| IFN‐gamma | 1 | pg/mL | 3.22 | 28.55 [<50] |

| sCD40L | 1 | pg/mL | 25.91 | 109.15 [80.3‐210.2] |

| TNF‐alfa | 1 | pg/mL | 0 | 0 [<50] |

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; IL, interleukin; INF, interferon; RT‐QuIC, real time quaking‐induced conversion; SCD40L, soluble CD40 ligand; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

The patient was treated with high‐dose intravenous methylprednisolone (1000 mg/day for 5 days), immediately followed by intravenous immunoglobulins (0.4 g/kg/day for 5 days). A clear EEG improvement was observed during the last day of immunoglobulin infusion, with disappearance of generalized periodic discharges. Anesthetics were withdrawn and antiepileptic drugs were reduced, followed by gradual improvement of consciousness with no relapse of seizures or myoclonus. A third brain MRI, performed 7 weeks after hospital admission, showed disappearance of the previously detected cortical abnormalities (Figure 2B).

In the following weeks, the patient regained a full functional status, including cognitive abilities, and was discharged home. At the follow‐up visit 6 months later, his neurological examination was unremarkable and no further seizure occurred.

Discussion

We report for the first time a probable association between COVID‐19 infection and a peculiar type of immune‐mediated encephalitis which closely resembles acute‐onset sCJD. Rapidly progressive cognitive dysfunction, focal myoclonus, EEG evolution to periodic sharp wave complexes, bilateral cortical DWI hyperintensities on brain MRI and 14‐3‐3 protein in the CSF were present in this case and were consistent with diagnostic criteria of sCJD. 7 , 8 Although a subacute onset is typical for sCJD, a stroke‐like onset has been recognized as a rare sCJD presentation. 9 , 10 , 11 In our case, this severe neurological picture was entirely driven by a COVID‐19‐ associated cytokine storm in both the CNS and bloodstream and was fully reversed by immunotherapy, leading to a complete neurological recovery.

A positive 14‐3‐3 protein in the CSF was reported in stuporous and comatose COVID‐19 patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies in the CSF. 12 14‐3‐3 protein is often present in the CSF of patients with sCJD (sensitivity 92% and a specificity of 80%) but can be detected also in the CSF of patients with other neurological conditions associated with neuronal injury. 13 In the present study, the positivity of the 14‐3‐3 could be the consequence of refractory status epilepticus. RT‐QuIC analysis of the CSF sample resulted negative. Moreover, the typical MRI pattern of sCJD includes cortical DWI hyperintensities associated with restricted diffusion on ADC map, 14 , 15 while ADC was not affected in our patient. The absence of hypointensity on ADC in retrospect should have suggested against a sCJD diagnosis. Our case further confirms that either a positive CSF 14‐3‐3 and/or a DWI MRI cortical ribboning, without evidence of restricted diffusion on ADC map, can lead to a misdiagnosis of sCJD.

A case of steroid‐responsive COVID‐19 encephalitis was reported, who presented with akinetic mutism, which is a core clinical symptom of sCJD. 16 These previous reports, together with our case, suggest that a COVID‐19‐associated autoimmune encephalitis could present as a sCJD‐like disorder, that needs to be recognized early and treated with immunotherapy to prevent an otherwise poor outcome. Similar to previously reported cases of COVID‐19‐related encephalitis, the CSF of our patient was negative for SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA and neuronal surface antibodies. SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies were not assessed in the CSF due to technical limitations of the available assay. Strikingly, the CSF tested normal on conventional analysis (protein count, cell count, glucose), despite a high content of pro‐inflammatory cytokines (IL‐6, IL‐23, IL‐31). The onset of encephalitis symptoms followed an asymptomatic COVID‐19 pneumonia by at least 10–14 days, since positive serum anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 IgG antibodies were found in the first week after admission. Overall, our case provides further evidence for an immune‐mediated, but likely not antibody‐mediated, mechanism of a subtype of COVID‐19‐associated encephalitis, which could be explained by cytokines release within the CNS and related neuroinflammation. Interestingly, a recent pathological study showed neuroinflammatory features of microglia and astrocytes from severe COVID‐19 patients. 17 Further studies are needed to assess the frequency of sCJD‐like presentation and confirm the response to immunotherapy, compared to other subtypes of COVID‐19‐associated encephalitis.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

S.B. and A.S. designed the study; S.B., A.S., C.B., J.C.D., A.P., R.R., M.B., F.A., P.C., F.M., G.G., G.F., G.B., and C.F. acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data; S.B. wrote the manuscript, which was critically revised by the other authors.

Informed Consent

A written informed consent was obtained from the patient for this publication.

References

- 1. Pilotto A, Masciocchi S, Volonghi I, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2‐related encephalitis: the ENCOVID multicenter study. J Infect Dis. 2021;223(1):28‐37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Paterson RW, Brown RL, Benjamin L, et al. The emerging spectrum of COVID‐19 neurology: clinical, radiological and laboratory findings. Brain. 2020;143(10):3104‐3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cao A, Rohaut B, Le Guennec L, et al. Severe COVID‐19‐related encephalitis can respond to immunotherapy. Brain. 2020;143(12):e102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zuhorn F, Omaimen H, Ruprecht B, et al. Parainfectious encephalitis in COVID‐19: "The Claustrum Sign". J Neurol. 2021;268(6):2031‐2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Serrano GE, Walker JE, Arce R, et al. Mapping of SARS‐CoV‐2 brain invasion and histopathology in COVID‐19 disease. Preprint. medRxiv. 2021;2021.02.15.21251511.

- 6. Matschke J, Lütgehetmann M, Hagel C, et al. Neuropathology of patients with COVID‐19 in Germany: a post‐mortem case series. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(11):919‐929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hermann P, Laux M, Glatzel M, et al. Validation and utilization of amended diagnostic criteria in Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease surveillance. Neurology. 2018;91(4):e331‐e338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zerr I, Kallenberg K, Summers DM, et al. Updated clinical diagnostic criteria for sporadic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 10):2659‐2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mead S, Rudge P. CJD mimics and chameleons. Pract Neurol. 2017;17(2):113‐121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Szabo K, Achtnichts L, Grips E, et al. Stroke‐like presentation in a case of Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18(3):251‐253. doi: 10.1159/000080109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hohler AD, Flynn FG. Onset of Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease mimicking an acute cerebrovascular event. Neurology. 2006;67(3):538‐539. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228279.28912.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alexopoulos H, Magira E, Bitzogli K, et al. Anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies in the CSF, blood‐brain barrier dysfunction, and neurological outcome: studies in 8 stuporous and comatose patients. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7(6):e893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Muayqil T, Gronseth G, Camicioli R. Evidence‐based guideline: diagnostic accuracy of CSF 14‐3‐3 protein in sporadic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease: report of the guideline development subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2012;79:1499‐1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vitali P, Maccagnano E, Caverzasi E, et al. Diffusion‐weighted MRI hyperintensity patterns differentiate CJD from other rapid dementias. Neurology. 2011;76(20):1711‐1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sacco S, Paoletti M, Staffaroni AM, et al. Multimodal MRI staging for tracking progression and clinical‐imaging correlation in sporadic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease. Neuroimage Clin. 2021;30:102523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pilotto A, Odolini S, Masciocchi S, et al. Steroid‐responsive encephalitis in coronavirus disease 2019. Ann Neurol. 2020;88(2):423‐427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang AC, Kern F, Losada PM, et al. Dysregulation of brain and choroid plexus cell types in severe COVID‐19. Nature. 2021;595(7868):565‐571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]