Edwards et al. (1) use synthetic cohort life tables to produce county-level estimates of the cumulative prevalence of contact with Child Protective Services (CPS) in the 20 most populous counties in the United States. Their findings are generated from state records of maltreatment submitted to the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) and foster care records submitted to the federal Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) (2, 3). Documenting lifetime CPS involvement is an incredibly important contribution to the literature (4–8). Cumulative estimates, however, are vulnerable to significant misestimation if first events are not accurately identified (9). And documenting a child’s first investigation, even within a state, poses unique challenges in national CPS data sources (4).

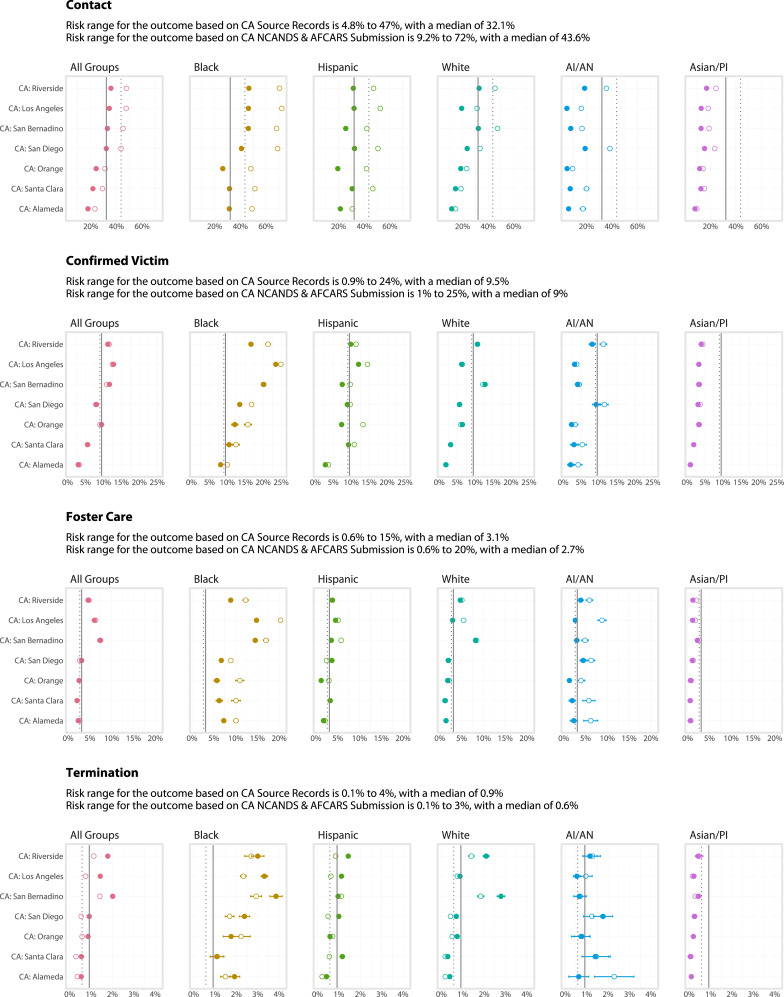

We use source CPS records from California to reproduce estimates for 7 of 20 counties in Edwards et al.’s (1) analysis. Our findings suggest that the cumulative prevalence of children investigated for maltreatment has been significantly overestimated (Fig. 1). For example, Edwards et al. estimate that 72% of Black children in Los Angeles will experience an investigation during childhood. Using their code, but drawing upon data that allow us to longitudinally observe a child’s combined investigation history under a single unique identifier, our estimate was significantly lower: 46% of Black children. Although we do not have data to make comparisons for non-California counties, we have no reason to think that those investigation estimates are not similarly compromised.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of cumulative risk estimates of CPS contact: California source records vs. Edwards et al.’s (1) estimates by race/ethnicity and county (2014–2018). California source estimates are shown as shaded dots ●; the median for all groups is depicted as a solid line. Edwards et al.’s estimates are shown as unshaded dots ○; the median for all groups is depicted as a dashed line. Counties are ordered from high to low based on overall contact. Each CPS outcome has its own x axis. The California source record analysis presented here falls under a university–agency data sharing agreement with the California Department of Social Services, which provides access to a fully longitudinal record of children’s first and subsequent CPS encounters. Importantly, the extracts of data we have access to (going back to 1998) are updated quarterly and organized into event files by the California Child Welfare Indicators Project at University of California, Berkeley. This permits us to directly observe changes to the unique identifier assigned to children and their associated encounter records over time, including records that may have been combined because of duplication or other data clean-up that may have occurred. Drawing upon these source records from California, we replicated the first encounter data structure detailed in code published by Edwards et al. We adopted their approach to coding race/ethnicity, used the same population estimates, and pulled records from the same 5-y window. We were unable to apply their imputation strategy, as that code was not publicly available. That said, the number of children with missing race/ethnicity was too low to explain the differences that emerged. We have included children with missing race/ethnicity in our overall “All Groups” estimates, consistent with the prior publication of investigations (4). AI/AN, American Indian/Alaska Native; PI, Pacific Islander.

Importantly, our analysis serves to largely validate estimates of “confirmed victims.” This is not surprising: States include, in their submissions to NCANDS, an indicator documenting whether a child was a “prior victim.” Likewise, AFCARS includes a foster care episode counter, and terminations of parental rights are unique events (5)—and we find that estimates generated using California source records generally align with those that were published. We do, however, observe unexplained differences in foster care entries for Black children. Counts released by Edwards et al. (1) suggest an unusual number of first entries estimated for adolescents, but only in 2014–2016. Documentation (3) indicates that there was a change in how duplicated records were reconciled in AFCARS submissions prior to 2005, which could contribute to inflated estimates for adolescents in 2014–2016, specifically. Further examination may be warranted.

In closing, we must acknowledge the seeming absurdity of questioning whether it is nearly 75% of Black children investigated in a given county during childhood or almost 50%, but the accuracy of these numbers matters. If a significant misestimation of investigation risk is allowed to stand without correction, it will erode trust in important sources of administrative data that can—and should—guide policy reforms. We hope that the comparisons presented here will provoke further examinations of data from other states, while also advancing important conversations around the structure and approach to state data submissions to NCANDS and AFCARS.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- 1.Edwards F., Wakefield S., Healy K., Wildeman C., Contact with Child Protective Services is pervasive but unequally distributed by race and ethnicity in large US counties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2106272118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect, National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) Child File FFY 2018. https:www.ndacan.acf.hhs.gov/datasets/dataset-details.cfm?ID=233. Accessed 3 August 2021.

- 3.National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect, AFCARS Foster Care Annual File User’s Guide. https://www.ndacan.acf.hhs.gov/datasets/pdfs_user_guides/afcars-foster-care-users-guide-2000-present.pdf. Accessed 3 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim H., Wildeman C., Jonson-reid M., Drake B.. Lifetime prevalence of investigating child maltreatment among US children. Am. J. Public Health 107, 274–280 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wildeman C., Edwards F. R., Wakefield S., The cumulative prevalence of termination of parental rights for U.S. children, 2000–2016. Child Maltreat. 25, 32–42 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wildeman C., Emanuel N., Cumulative risks of foster care placement by age 18 for U.S. children, 2000-2011. PloS One 9, e92785 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wildeman C., et al. , The prevalence of confirmed maltreatment among US children, 2004 to 2011. JAMA Pediatr. 168, 706–713 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putnam-Hornstein E., et al. , Cumulative rates of child protection involvement and terminations of parental rights in a California birth cohort, 1999–2017. Am. J. Public Health 111, 1157–1163 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Namboodiri K., Suchindran C. M., Life Table Techniques and Their Applications (Academic, 1987). [Google Scholar]