Long-term care homes (LTCHs) were at the epicentre of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Canada and were the sites where most deaths occurred.1 With increased morbidity and mortality of residents in the LTCH setting, clinician burnout risk is high, and team debriefs, especially after the death of a resident, offer a structured way to support team health and enhance clinicians’ ability to continue to provide high-quality care during and after the pandemic. This article describes the case of a LTCH resident with advanced dementia who was the first COVID-19–positive resident in this facility. Family physicians are often called on to lead team debriefs in LTCHs. We seek to explore the core elements of team debriefing, including the barriers faced by LTCHs to support this practice, and make recommendations.

Case

An 82-year-old female LTCH resident was diagnosed with COVID-19 in April 2020. She had been admitted to the LTCH in 2019 with advanced dementia. She had the first case of COVID-19 in this LTCH. The resident presented with a fever but no other symptoms of COVID-19. Her test swab results for COVID-19 were positive and her substitute decision maker was informed of the test result that same day. Goals of care were reviewed and followed symptom control and no hospital transfer protocol. Because of visitor restrictions, the resident’s family members were not able to visit in person, but they were updated by telephone by the most responsible physician (MRP) over the ensuing days. On day 7, the resident required oxygen at 2 L per min via nasal prongs for hypoxia. Midday on day 8, the resident became confused and restless, intermittently pulling at her oxygen tubing. On day 9, the resident was started on a continuous subcutaneous infusion of fluid for hydration as she had stopped eating and drinking. She became tachypneic and was prescribed 0.5 mg of subcutaneous hydromorphone every 4 hours as needed. The resident continued to labour in her breathing and became audibly congested. The next morning, her hydromorphone was converted to scheduled dosing and the continuous subcutaneous infusion for hydration was discontinued. The resident died that evening.

The following week, the resident’s care team assembled for a debriefing. The resident’s MRP, personal support worker, registered practical nurse, registered nurse, and the LTCH’s director of care attended. The MRP led the debriefing session. The resident’s long-standing personal support worker wept and expressed sadness about the resident’s distress during her last days of life and about her dying without the presence of her family. The resident’s nurse raised concerns regarding the rapidity of the resident’s decline, as well as about the stress of working in an understaffed environment and the internal tension involved in balancing the provision of compassionate care to this resident while following infection control and prevention measures. The MRP shared his own personal distress over his discomfort in managing severe respiratory distress. The team members also described communication challenges that were contributing to their distress, such as lacking the language and skills to help them respond to strong emotions, such as anger due to visitor policy restrictions, a sentiment that patients and families expressed. The director of care offered advice and supportive counseling. The team acknowledged that establishing goals of care early on in the resident’s trajectory had been helpful. They felt that having a standardized approach to establishing goals of care and having earlier advance care planning conversations for all residents would enhance resident care and lessen provider discomfort. The team members discussed that inviting a palliative care consultant to future debriefings could add an additional layer of support for staff, anticipating that other residents might experience severe symptoms related to COVID-19 or that in future situations communications strategies could assist with challenging discussions. All participants in the debrief acknowledged the value of the debrief and requested that a similar process be adopted in their LTCH for all deaths.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic is causing substantial challenges and suffering for residents and providers working in LTCHs. In Canada, LTCHs became the epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic, with more than 80% of COVID-19 deaths occurring among residents of these care homes.1 The uncertainty, complexity, and rapid clinical changes associated with COVID-19, and the separation of these patients from their loved ones, highlight the need for team-based approach to provide high-quality care to those living with serious illness. Moreover, the unrelenting clinical workload leaves little time to reflect on, or process, the clinician grief caused by COVID-19. This is likely contributing to increased clinician burnout risk, which has negative personal, patient and family, and systems-level implications. Therefore, interventions prioritizing team health are essential to ensuring a healthy and capable front-line work force in LTCHs. Debriefing after difficult health encounters, including resident deaths, is one way to enhance team health and to maximize our ability to provide care during and after the pandemic. As such, it is prudent to consider team debriefs after crisis events, including after the death of a resident experiencing the rapid clinical changes and severe respiratory distress due to COVID-19. It is also important to debrief after team successes and when both team and health system protocols work effectively to provide the best care.

Debriefing originated in the military, where soldiers would meet to discuss an event with the goal of identifying errors and reducing psychological stress.2 Clinically, debriefing has been used after critical events to discuss individual and team performance, knowledge, and cognitive decision making.3 This framework, referred to as crisis resource management, decreases mental workload and potentially improves clinical outcomes.4-6 When there is a particularly difficult case, providing care to a resident can be distressing, leaving staff drained or upset because of unresolved questions and emotions. It can be challenging for staff to go forward after such a case, whether or not it resulted in the resident’s death. Grief is a natural reaction to loss or death, and is experienced differently by each staff member. When grief is present in LTCHs and is not addressed, staff are at risk for compassion fatigue and disenfranchised grief.7 Peer-led debriefing has been used effectively as a tool for grief support in LTCHs.8

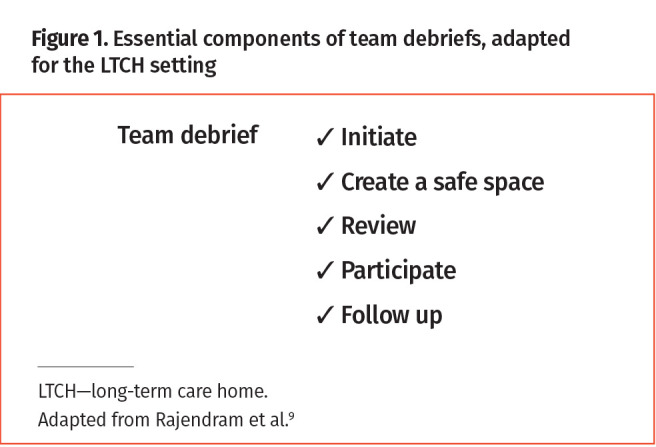

Debriefing is a guided process that aims to review and understand critical experiences, including death. Based on our experiences in LTCHs throughout the pandemic, the key components of a team debrief are as follows: debriefs are initiated by identifying a debriefing leader, who announces and invites team members to the session. Ideally, a debrief is scheduled soon after the death of a resident or a health crisis, in part to immediately address and diffuse the emotions associated with it, but this timing is subject to scheduling and circumstances within the LTCH. A safe space is created by ensuring a flat hierarchy and maintaining privacy for the participating team members. There should be a “no-blame” and a “nonthreatening” environment. The process of review involves the debriefing leader identifying the chronology of events, allowing all team members to provide their own perspectives, and asking whether there are any unanswered questions. Team successes and challenges alike should be reflected on and discussed. Any personnel, process, and equipment issues should be raised and discussed. Communication can be highlighted, discussing both enablers of and barriers to effective communication. Critiques of any individual’s performance should be avoided. The debriefing leader should ensure all team members have an equal opportunity to speak or to “pass” on direct questions that might arise. The debriefing leader then creates an opportunity to discuss what the staff might need as a group, or individually, to manage, either through their current shift or moving forward, their physical, cognitive, emotional, and self-care needs. Opportunity should be given to understand the impact of the experience on the team members, normalizing reactions and promoting a sense of team support. The final component of a team debrief includes planning and follow-up. Voiced concerns should be tracked and followed up, with referral to professional services if appropriate. The option for individuals to discuss concerns privately should also be made available. A summary of the essential components of team debriefs has been adapted and is presented in Figure 1.9

Figure 1.

Essential components of team debriefs, adapted for the LTCH setting

Anecdotally, debriefing in our LTCH during the pandemic identified opportunities to enhance communication training so as to better equip clinicians with the language and skills to expertly respond to patient and family emotion (eg, anger, frustration, guilt, etc) during a challenging time. Existing Web-based, virtual, and in-person training programs, such as the Serious Illness Care Program (www.ariadnelabs.org), VitalTalk (www.vitaltalk.org), and Learning Essential Approaches to Palliative Care (www.pallium.ca), are available for interprofessional teams to gain the knowledge and skills to feel more comfortable in this area. Using a structured approach to guide a goal-directed conversation has been shown to be feasible,10 while learning component communication skills led to favourable clinician and patient outcomes.11 Investing in time to debrief a challenging situation allowed this team to identify an organizational learning opportunity that has the potential to enhance resiliency and might improve resident and family outcomes.

There are several barriers to having a team debrief, including in the setting of LTCHs. Understaffed LTCHs and competing resident care demands become a serious challenge. Other barriers include lack of a private space in the clinical area, disinterest by some team members, lack of support from administration, and fear of team members being judged or scrutinized for clinical work or decision making.12 Given the unique challenges of having immediate debriefing sessions in LTCHs during the COVID-19 pandemic, becoming familiar with the essential components of team debriefing might aid in one’s confidence to implement debriefings. Consider developing partnerships with palliative care clinicians as they are well placed to facilitate these debriefs, given their empathetic communication skills training, extensive experience leading and navigating difficult conversations, and expertise in serious illness care.

Conclusion

Team debriefs in the setting of LTCHs, where COVID-19 is causing substantial suffering, have the potential to be effective, high-return interventions that can be offered routinely or in response to crisis to promote team health and minimize the risk of compassion fatigue and disenfranchised grief, and can create action plans that mitigate future crises. Core components of team debriefs in this setting include initiating the debrief; creating a safe space; reviewing the clinical events; assessing resultant individual, team, and organizational impacts; doing a needs assessment; and creating a plan for follow-up and closure.

Editor’s key points

▸ In long-term care homes, team debriefs are a tool to reduce compassion fatigue and disenfranchised grief of staff, and to identify growth opportunities for the team and organization.

▸ A team debrief is a guided process that aims to review and understand the facts and emotions of lived experiences, including those surrounding the death of a long-term care home resident.

▸ Core features of a successful team debrief include initiating a debriefing session, creating a safe space, reviewing the clinical events, doing a needs assessment, and creating a plan for follow-up and closure.

Points de repère du rédacteur

▸ Dans les centres de soins de longue durée, le débreffage en équipe est un outil pour réduire l’épuisement compassionnel et aborder la privation du deuil chez les membres du personnel, de même que pour identifier des possibilités de croissance pour l’équipe et l’organisation.

▸ Le débreffage en équipe est un processus guidé qui a pour but de revoir et de comprendre les faits et les émotions des expériences vécues, y compris ceux entourant le décès d’un résident d’un centre de soins de longue durée.

▸ Les principales caractéristiques de la réussite d’un débreffage en équipe comprennent l’initiative de tenir une telle séance, la création d’un espace sécuritaire, la revue des événements cliniques, l’évaluation des besoins et la production d’un plan de suivi et de résolution du deuil.

Footnotes

Competing interests

None declared

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

References

- 1.COVID-19 daily epidemiology update. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2020. Available from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/epidemiological-summary-covid-19-cases.html. Accessed 2020 Mar 26. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter LA. Debriefing and feedback in the current healthcare environment. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 2016;30(3):174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg GM, Hervey AM, Basham-Saif A, Parsons D, Acuna DL, Lippoldt D.. Acceptability and implementation of debriefings after trauma resuscitation. J Trauma Nurs 2014;21(5):201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coppens I, Verhaeghe S, Van Hecke A, Beeckman D.. The effectiveness of crisis resource management and team debriefing in resuscitation education of nursing students: a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Nurs 2018;27(1-2):77-85. Epub 2017 Jun 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boet S, Sharma B, Pigford AA, Hladkowicz E, Rittenhouse N, Grantcharov T.. Debriefing decreases mental workload in surgical crisis: a randomized controlled trial. Surgery 2017;161(5):1215-20. Epub 2017 Jan 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couper K, Salman B, Soar J, Finn J, Perkins GD.. Debriefing to improve outcomes from critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 2013;39(9):1513-23. Epub 2013 Jun 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boerner K, Burack OR, Jopp DS, Mock SE.. Grief after patient death: direct care staff in nursing homes and homecare. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49(2):214-22. Epub 2014 Jul 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulz M. Taking the lead: supporting staff in coping with grief and loss in dementia care. Healthc Manage Forum 2017;30(1):16-9. Epub 2016 Dec 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajendram P, Notario L, Reid C, Wira CR, Suarez JI, Weingart SD, et al. Crisis resource management and high-performing teams in hyperacute stroke care. Neurocrit Care 2020;33(2):338-46. Epub 2020 Aug 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lakin JR, Koritsanszky LA, Cunningham R, Maloney FL, Neal BJ, Paladino J, et al. A systematic intervention to improve serious illness communication in primary care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(7):1258-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, Olsen MK, Jeffreys AS, Rodriguez KL, et al. Enhancing communication between oncologists and patients with a computer-based training program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2011;155(9):593-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullan PC, Kessler DO, Cheng A.. Educational opportunities with postevent debriefing. JAMA 2014;312(22):2333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]