SARS-CoV-2 infections have caused substantial mortality and morbidity, including thrombocytopenia, thromboses, and their co-occurrence.1 COVID-19 vaccines have prevented hospitalisations and deaths worldwide,2 showing real-world effectiveness.3 AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCov-19) is used in more than 170 countries,4 with more than 2 billion doses supplied to date (Nov 17, 2021). During real-world use of COVID-19 vaccines, an extremely rare adverse event was reported: thrombosis associated with thrombocytopenia (thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome [TTS]).1 The risks of these events were substantially higher after SARS-CoV-2 infection than vaccination.1 Ongoing AstraZeneca standard safety monitoring for AZD1222 showed reporting rates of 8·1 potential TTS cases per million vaccinees within 14 days of first-dose administration and 2·3 potential TTS cases per million vaccinees within 14 days of second-dose administration through April 30, 2021.5

TTS has been reported from different geographical regions in which AZD1222 has been used in diverse populations of various ages and with different risk factors. We present TTS reporting rates following AZD1222 vaccination from spontaneous reporting across a broad geographical distribution, representing all reported cases captured in the AstraZeneca global safety database until August 31, 2021 (appendix p 1).

To calculate TTS reporting rates, countries in which vaccine administration was tracked and data made available were identified, and the number of reports from the respective countries were divided by the number of vaccine doses administered. TTS cases were identified in the AstraZeneca global safety database with searches for events within 21 days of vaccination using standardised Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (version 24.0) queries for “embolic and thrombotic events” and “haematopoietic thrombocytopenia”, and the high-level term “thrombocytopenias”, broadly reflecting the Brighton Collaboration definition of TTS.6 All reported cases were included in the calculation of TTS reporting rates, regardless of classification as definite, probable, or possible cases. The US Truven MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database was used to calculate the background TTS rate in an unvaccinated prepandemic population. Two methods of calculation of background TTS rate were used, both of which were amended from a previous analysis5 to use a 21-day timeframe instead of 14 days to reflect the evolving definition of TTS. In the first method, TTS was defined as primary or unspecified thrombocytopenia occurring between 7 days before and 7 days after a thrombosis event (focused on thrombosis of limbs, splanchnic region, and cerebral or pulmonary embolism), restricted to patients without a history of thrombocytopenia or thrombotic event in the previous 12 months. In the second method, TTS was defined as primary or unspecified thrombocytopenia occurring the day before, or 14 days after, thrombosis.5

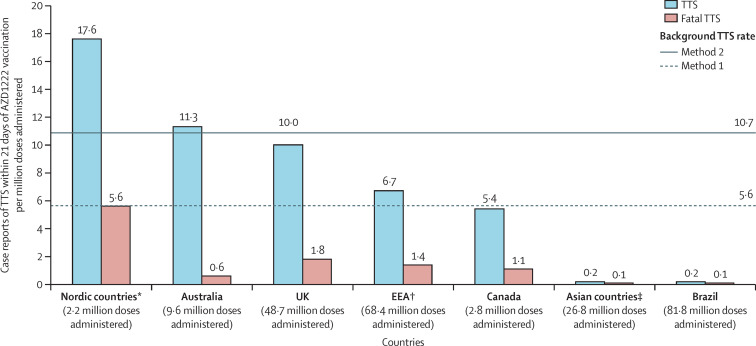

TTS reporting rates (cases per million doses administered per 21 days) ranged from 17·6 in Nordic countries to 0·2 in Asian countries and Brazil (figure ; estimated background rate, prepandemic population: 5·6–10·7 events per million persons per 21 days), suggesting geographical differences in TTS risk. TTS-related fatality rates per million doses administered were heterogenous but low in Asian countries and Brazil (<0·1 to 0·2), and in Australia, Spain, France, Canada, and Italy (0·6 to 1·3; figure; appendix p 1).

Figure.

Reporting rate for TTS and TTS fatality rate following AZD1222 vaccination by regions and countries

EEA=European Economic Area. TTS=thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Background TTS rate estimated in an unvaccinated prepandemic population using the US Truven MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database. In method 1 for calculation of background TTS rate, TTS was defined as primary or unspecified thrombocytopenia occurring between 7 days before and 7 days after a thrombosis event (focused on thrombosis of limbs, splanchnic region, and cerebral or pulmonary embolism), restricted to patients without a history of thrombocytopenia or thrombotic event in the previous 12 months; in method 2, TTS was defined as primary or unspecified thrombocytopenia occurring the day before, or 14 days after, thrombosis. Exposure data from the EEA, Australia, the UK, Canada, Asian countries and Brazil are from data-lock point (Aug 31, 2021). *Nordic countries are Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. †EEA includes the Nordic countries. ‡Asian countries included are the Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Observed differences in TTS rates could result from a number of potential country-level differences, which need to be assessed. The potential effect of country-based reporting differences on observed TTS rates was investigated by analysing the reporting rates for another rare adverse event, anaphylaxis, which is well defined and prompts urgent care (appendix p 1). In the Philippines, which had a low TTS rate, anaphylaxis was reported at a much higher rate, suggesting that factors other than reporting system differences might contribute to the low TTS rate observed in this analysis. For South Korea, the low observed TTS rate is consistent with a national claims database analysis reporting an observed rate of intracranial venous thrombosis within 2 weeks of vaccination of 0·23 per million individuals;7 however, additional evaluation is required. The low reporting rates for TTS and anaphylaxis in Brazil require additional investigation; these rates suggest lower overall spontaneous reporting. Differences in TTS rates could also result from variations in country-specific vaccine use recommendations, with some countries prioritising vaccination of potentially younger and predominantly female health-care workers (appendix p 1), or in reporting behaviours (eg, understanding and awareness of TTS associated with the timing of the start of the vaccination programme; appendix p 1). Environmental factors and genetic factors (eg, ethnicity) could also result in differences in susceptibility, as suggested by reports of relevant medical history and risk factors in studies of Ad26.COV2.S;8, 9 this requires additional investigation. The extreme rarity of TTS suggests that multiple concurrent risk factors are probably required for an individual to develop it.

The data herein are important to inform and prompt country-specific risk:benefit evaluations. A better understanding of optimal TTS management is important as vaccination continues globally. Global collaboration and detailed spontaneous reporting are essential to understand and minimise the risk of very rare adverse events, including TTS. Vaccine confidence, derived from risk minimisation and benefit optimisation, remains a key driver for ending the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgments

All authors are employees of AstraZeneca and might have stock options. All authors contributed to the development of the manuscript, including interpretation of results, substantive review of drafts, and approval of the final draft for submission. NKS accessed and verified the data. The authors acknowledge Rebecca A Bachmann, AstraZeneca, for facilitating author discussion and for critical review of the manuscript. Medical writing and editing support for the development of this manuscript, under the direction and guidance of the authors, was provided by Jennifer Steeber and Steve Hill, of Ashfield MedComms, an Ashfield Health company, in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines. This support was funded by AstraZeneca.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Hippisley-Cox J, Patone M, Mei XW, et al. Risk of thrombocytopenia and thromboembolism after covid-19 vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 positive testing: self-controlled case series study. BMJ. 2021;374 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galvani AP, Moghadas SM, Schneider EC. Deaths and hospitalizations averted by rapid U.S. vaccination rollout. 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2021/jul/deaths-and-hospitalizations-averted-rapid-us-vaccination-rollout

- 3.Lopez Bernal J, Andrews N, Gower C, et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:585–594. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holder J. Tracking coronavirus vaccinations around the world. 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/world/covid-vaccinations-tracker.html

- 5.Bhuyan P, Medin J, da Silva HG, et al. Very rare thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after second AZD1222 dose: a global safety database analysis. Lancet. 2021;398:577–578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01693-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen RT, Black S. Updated Proposed Brighton Collaboration process for developing a standard case definition for study of new clinical syndrome X, as applied to Thrombosis with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome (TTS) 2021. https://brightoncollaboration.us/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/TTS-Interim-Case-Definition-v10.16.3-May-23-2021.pdf

- 7.Huh K, Na Y, Kim YE, Radnaabaatar M, Peck KR, Jung J. Predicted and observed incidence of thromboembolic events among Koreans vaccinated with ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36:e197. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takuva S, Takalani A, Garrett N, et al. Thromboembolic events in the South African Ad26.COV2.S vaccine study. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:570–571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2107920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.See I, Su JR, Lale A, et al. US case reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, March 2 to April 21, 2021. JAMA. 2021;325:2448–2456. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.