Abstract

Hyperuricemia (HUA) is a metabolic disease, closely related to oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, caused by reduced excretion or increased production of uric acid. However, the existing therapeutic drugs have many side effects. It is imperative to find a drug or an alternative medicine to effectively control HUA. It was reported that Gardenia jasminoides and Poria cocos could reduce the level of uric acid in hyperuricemic rats through the inhibition of xanthine oxidase (XOD) activity. But there were few studies on its mechanism. Therefore, the effective ingredients in G. jasminoides and P. cocoa extracts (GPE), the active target sites, and the further potential mechanisms were studied by LC-/MS/MS, molecular docking, and network pharmacology, combined with the validation of animal experiments. These results proved that GPE could significantly improve HUA induced by potassium oxazine with the characteristics of multicomponent, multitarget, and multichannel overall regulation. In general, GPE could reduce the level of uric acid and alleviate liver and kidney injury caused by inflammatory response and oxidative stress. The mechanism might be related to the TNF-α and IL-7 signaling pathway.

1. Introduction

Hyperuricemia (HUA) is the biochemical basis of gout, mainly caused by the decreased excretion or increased production of uric acid or both. In recent years, the number of patients with HUA has increased significantly, and it has shown a development trend of rejuvenation [1]. Uric acid is produced by xanthine oxidase (XOD), which could promote the activation of reduced coenzyme II (NAPDH) and the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing renal oxidative stress [2, 3]. Uric acid at normal concentrations exerts antioxidant effects in vivo but above normal physiological levels can act as a prooxidant to expand the body's oxidative stress damage [4–6]. While oxidative stress responses can activate inflammatory factors in kidney cells and induce innate immune responses in vivo, the activation of related proinflammatory factors induces the development of inflammation [7–9]. Hyperuricemia has been reported to be closely related to oxidative stress and inflammatory responses [10]. At present, the drugs for the treatment of HUA in clinical practice including allopurinol, benzbromarone, and sodium bicarbonate can control the level of uric acid, but they have a series of toxic side effects such as liver and kidney function injury and hematopoietic dysfunction [11, 12]. Therefore, it is a hotspot to find the low-toxic and efficient antigout drugs from traditional Chinese medicine.

The fruit of Gardenia jasminoides is a traditional Chinese medicine which is commonly used to cure fever, red swelling, and pain [13]. Poria cocos could promote diuresis and dampness, strengthen the spleen, and calm the heart and is mainly used for the treatment of edema and diuretic detumescence medicine [14, 15]. G. jasminoides extracts can reduce uric acid levels in hyperuricemic mice by inhibiting XOD activity [16], but there are few studies on its mechanism.

Network pharmacology is a new method that integrates chemoinformatics, bioinformatics, traditional pharmacology, biological networks, and network analysis. Based on network pharmacology, the comprehensive network construction of medicinal components-active targets-disease targets of Chinese medicine can make the generalization of the pharmacological characteristics of Chinese medicine more comprehensive. In this study, the network pharmacology method combined with molecular docking was used, and the active ingredients in G. jasminoides and P. cocoa extracts (GPE) were used as the research objects to explore the efficacious ingredients, active targets, and potential mechanisms of GPE to reduce the high uric acid. Furthermore, animal experiments were carried out to verify the pharmacological effects of GPE.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.1.1. Instrument

Ultraperformance liquid chromatograph was purchased from Waters (Massachusetts, USA). High-resolution mass spectrometer (Q Exactive) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Massachusetts, USA). Hypersil GOLD aQ column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Massachusetts, USA). A low-temperature high-speed centrifuge (Centrifuge 5430) was purchased from Eppendorf (Hamburg, Germany). A vortex finder (QL-901) was purchased from Qilinbeier Instrument Manufacturing Co., Ltd. (Haimen, China). A pure water meter (Milli-Q) was purchased from Integral Millipore Corporation (Massachusetts, USA).

2.1.2. Reagent

d3-Leucine, 13C9-phenylalanine, d5-tryptophan, and 13C3-progesterone were used as internal standard. Methanol (A454-4) and acetonitrile (A996-4) were both chromatographic reagents, which were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Massachusetts, USA). Ammonium formate (17843–250 G) was obtained from Honeywell Fluka (New Jersey, USA). Formic acid (50144–50 mL) was obtained from DIMKA (Los Angeles, USA).

2.1.3. Materials

Gardenia jasminoides Ellis (1 kg) and Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf (1 kg) were purchased from the Yuzhou Medicinal Material Market (Yuzhou, China) and identified as Gardenia jasminoides Ellis (Rubiaceae) and Poria cocos (Schw.) by Professor Changqin Li at Henan University (Kaifeng, China). The voucher specimen (20200718) was deposited in the National Research and Development Center of Edible Fungi Processing Technology, Henan University.

2.1.4. Preparation of Sample

The dried fruits of G. jasminoides and the dried sclerotia of P. cocos (1 : 1) were soaked in 15 L of water and decocted for 60 min and then filtered. The filter residues were decocted in 10 L of water for 30 min and filtered. The two filtrates were combined and freeze-dried to obtain GPE with a yield of 11%.

2.2. Chromatographic Methods

2.2.1. Chromatographic Conditions

Hypersil GOLD aQ column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm) was used. The mobile phase was 0.1% formic acid-water (liquid A) and 0.1% formic acid-acetonitrile (liquid B) with the sequence as 0–2 min 5% B; 2–22 min 5–95% B; 22–27 min 95% B; 27.1–30 min 5% B. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min, the column temperature was 40°C, and the injection volume was 5 μL [17].

2.2.2. Mass Spectrometry Conditions

The mass range was set at 150–1500 daltons, the MS resolution was 70000, the AGC was 1e6, and the maximum injection time was 100 ms. According to the strength of the MS ions, the top 3 peaks were selected for fragmentation. The MS2 resolution was 35000, AGC is 2e5, the maximum injection time was 50 ms, and the fragmentation energy was set as 20, 40, and 60 eV. Ion source (ESI) parameter settings are as follows: sheath gas flow rate was 40 arb, aux gas flow rate was 10 arb, spray voltage of positive ion mode was 3.80 kV, spray voltage of negative ion mode was 3.20 kV, ion capillary temp was 320°C, and aux gas heater temp was 350°C [17].

2.2.3. Data Analysis

UPLC-MS/MS technology was used to systematically analyze the chemical constituents of GPE with positive and negative ion modes, respectively. The compounds were identified by comparing the retention time, accurate molecular weight, and MS2 data with standard databases such as MZVault, MZCloud, and BGI Library (self-built standard Library by BGI Co., Ltd.).

2.3. Screening and Target Prediction of Active Compounds in GPE

The effective ingredients of GPE were screened by TCMSP database and LC-MS-MS identification results. The screening condition is oral bioavailability (OB) ≥ 30%. Drug likeness (DL) is greater than ≥0.18. At the same time, the target prediction of the Swiss target prediction platform is used. UniProt is used to standardize the names of the screened target proteins.

2.4. Acquisition of HUA Disease Targets

“High uric acid” as a keyword was used to search and screen databases such as GeneCards, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), PharmGkb, TTD, and DrugBank. Venny 2.1.0 was used to draw a Venn diagram to obtain HUA disease target.

2.5. Construction and Analysis of Protein Interaction Network

Venny 2.1.0 was used to draw a Venn diagram and to obtain the intersection of GPE and the effective ingredients with the hyperuricemia target, which was the possible target of GPE in the treatment of hyperuricemia, and the intersection would be the target. A PPI protein interaction network was established in the database of the biomolecular functional annotation system STRING (https://string-db.org/), and the analysis was performed based on the results.

2.6. Topological Analysis of Protein Interaction Network (CytoNCA)

The PPI protein interaction files was imported and obtained from the STRING (https://string-db.org/) database into Bisogenet of Cytoscape to construct the PPI protein interaction network. CytoNCA in Cytoscape was used to perform topological analysis on the interaction network. The core network and key proteins for the treatment of HUA were obtained.

2.7. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) was used to mainly analyze the gene and protein functions of various species from the three aspects: biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis is commonly used to clarify the role of target proteins in signaling pathways. In this study, the clusterProfiler program package in R language was used to perform GO enrichment analysis and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway analysis on shared targets. The corresponding target proteins in the GPE were directly mapped on the pathway where the drug target is enriched as the pathway for drug therapy, and a bubble chart is drawn for visualization.

2.8. Molecular Docking

The 3D structure of the compound in GPE was obtained from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and screened from the RCSB PDB (http://www.rcsb.org/) database. The water molecules and small ligand molecules of the core target protein from the crystal structure were removed, and the structure of the potential protein isolated. The genetic algorithm in the SYBYL-X software was used for semiflexible docking. The center coordinates and size of the box were set according to the position of the active site of the protein molecule and the area where it might have an effect on the small molecule of the ligand. The remaining parameters remained as default. The target protein was subjected to molecular docking analysis.

2.9. Animal Experiments

2.9.1. Materials and Reagents

Potassium oxonate was purchased from Yuanye Biological Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Benzbromarone was purchased from Heumann Pharma GmbH (Kunshan, China). CMC-Na was purchased from Shanghai Chemical Reagent Station Branch Factory (Shanghai, China). Uric acid (UA) content detection kit and XOD activity detection kit were purchased from Solaibao Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Total superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), malondialdehyde (MDA), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cr), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin (IL-2), interleukin-4 (IL-4), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) detection kits were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). NADPH oxidase (NADPH-OX) kit, reactive oxygen species (ROS) kit, and β2 microglobulin (β2-MG) kit were purchased from Shanghai Jining Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.9.2. Animals and Experimental Design

(1) Animals. Forty Specific Pathogen-Free (SPF) Sprague-Dawley (SD) male rats were provided by the Henan Laboratory Animal Center (laboratory animal license number: SCXK (Yu) 2017-0001). The rats were adapted for one week (temperature 25 ± 2°C, light circle 12 h/d, humidity 40 to 45%) before the experiment and fed with a standard diet with free access to water.

2.9.3. Experimental Grouping and Administration

Thirty-six rats were randomly divided into six groups: blank control (BC) group, model control (MC) group, positive control (PC) group, GPE high-dose group (GPE-HD, 1000 mg/kg), medium-dose group (GPE-MD, 500 mg/kg), and low-dose group (GPE-LD, 250 mg/kg). The dosage of benzbromarone for the PC group was 8 mg/kg, and it was suspended with an appropriate amount of 0.5% CMC-Na. The BC group was administered with the same volume of 0.5% CMC-Na without benzbromarone.

2.9.4. Establishment of Hyperuricemic Rat Model

Animal groups of GPE-HD, GPE-MD, and GPE-LD were administered for 15 d. Except for the blank group, the other groups were intraperitoneally injected with 300 mg/kg potassium oxonate 1 h before the last oral administration, and the blank group was injected with an equal volume of 0.5% CMC-Na. Two hours after the last administration, blood was collected from the abdominal aorta and centrifuged. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 3500 g for 10 min. The tissues of the liver and kidney were collected and frozen in a -80°C freezer.

2.9.5. Determination of Inflammatory Factors in Rat Plasma

The contents of IL-2, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-1β in plasma were measured according to the ELISA kit instructions.

2.9.6. Determination of Antioxidative Stress Ability in Rats

The liver tissues were collected to make tissue homogenates at the corresponding concentrations, and the activities of XOD, SOD, NADPH-OX, ROS, GSH-PX, T-AOC, CAT, and MDA in plasma and tissues were measured, respectively, according to the kit instructions.

2.9.7. Effects of Samples on Liver and Kidney Function Injury

The contents of BUN, Cr, β2-MG, and XOD in plasma were determined in strict accordance with the kit instructions.

2.9.8. Pathological Changes of Liver and Kidney Tissues

Two hours after the last oral administration, the liver and kidney tissues were collected, washed with cold saline, fixed in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde solution for 24 h, rinsed in PBS for 6 h, dehydrated and embedded, then sliced into 5 μm sections by a microtome, stained with H&E, and observed and photographed under a microscope.

2.9.9. Detection of Uric Acid Levels in Rat Plasma

The content of UA in plasma was measured within 15-20 min in strict accordance with the kit instructions.

2.9.10. Statistical Processing

SPSS 19.0 software was used to process statistical data. Differences of data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). P < 0.05 was considered significantly different.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Effective Ingredient Screening and Target Prediction in GPE

Based on TCMSP database and LC-MS-MS identification results, the effective ingredients and target prediction data of GPE were selected (in Tables 1 and 2), and 30 effective compounds and corresponding gene targets of the GPE were obtained. The specific effective ingredients from GPE are illustrated in Table 3.

Table 1.

The compounds identified from GPE by LC-MS-MS in positive model.

| RT (min) | Adducts | Formula | Measured value | Molecular weight | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.871 | [M+H]+ | C10H14N5O7P | 347.06293 | 348.07007 | Adenosine 5′-monophosphate |

| 1.012 | [M+H]+ | C6H14O6 | 182.07906 | 183.08633 | Galactitol |

| 1.115 | [M+H]+ | C9H11NO3 | 181.07413 | 182.08142 | L-tyrosine |

| 1.12 | [M+H]+ | C10H13NO4 | 267.09656 | 268.1037 | Adenosine |

| 3.05 | [M+H]+ | C11H9NO2 | 187.06352 | 188.0708 | Indole-3-acrylic acid |

| 3.834 | [M+H]+ | C16H26O8 | 346.16224 | 347.17001 | Jasminoside B |

| 3.978 | [M+H]+ | C10H12N2 | 160.10024 | 161.10744 | Tryptamine |

| 4.18 | [M+H]+ | C10H14O | 150.1046 | 151.11189 | Carvone |

| 4.607 | [M+H]+ | C14H14N2O5 | 290.09014 | 291.09741 | Indole-3-acetyl-l-aspartic acid |

| 5.912 | [M+H]+ | C15H22O2 | 234.16208 | 235.16927 | Artemisinic acid |

| 6.153 | [M+H]+ | C33H40O19 | 740.21617 | 741.22345 | Mauritianin |

| 6.216 | [M+H]+ | C10H10O4 | 194.05802 | 195.06546 | Isoferulic acid |

| 6.274 | [M+H]+ | C10H16O | 152.12026 | 153.12759 | α-Pinene-2-oxide |

| 6.295 | [M+H]+ | C27H30O16 | 610.15294 | 611.16016 | Rutin |

| 6.357 | [M+H]+ | C27H30O16 | 610.15294 | 611.15985 | Rutin |

| 6.514 | [M+H]+ | C10H12O2 | 164.08388 | 165.09126 | 4-Phenylbutyric acid |

| 6.526 | [M+H]+ | C21H20O12 | 464.09551 | 465.10303 | Isoquercitrin |

| 6.531 | [M+H]+ | C15H10O7 | 302.04238 | 303.04974 | Quercetin |

| 6.84 | [M+H]+ | C27H30O15 | 594.1591 | 595.16565 | Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside |

| 7.252 | [M+H]+ | C9H8O3 | 164.04749 | 165.05476 | 3-Hydroxycinnamic acid |

| 7.407 | [M+H-H2O]+ | C10H10O4 | 194.058 | 177.05469 | Ferulic acid |

| 10.436 | [M+H]+ | C12H17NO | 191.13118 | 192.13846 | DEET |

| 10.839 | [M+H]+ | C21H32O2 | 316.24007 | 317.24747 | Pregnenolone |

| 11.096 | [M+H]+ | C15H18O2 | 230.13068 | 231.13805 | Dehydrocostus lactone |

| 12.931 | [M+H]+ | C24H30O6 | 414.20437 | 415.21176 | Bis(4-ethylbenzylidene)sorbitol |

| 13.036 | [M+H]+ | C20H34O2 | 306.25575 | 307.26303 | 11(z),14(z),17(z)-Eicosatrienoic acid |

| 14.969 | [M+H]+ | C18H30O2 | 278.22439 | 279.23169 | Α-Eleostearic acid |

| 15.833 | [M+H]+ | C18H30O3 | 294.21933 | 295.22665 | 9-Oxo-10(e),12(e)-octadecadienoic acid |

| 16.83 | [M+H]+ | C22H32O2 | 328.24016 | 329.24728 | Docosahexaenoic acid |

| 17.661 | [M+H]+ | C21H38O4 | 354.27686 | 355.28418 | 1-Linoleoyl glycerol |

| 17.749 | [M+H]+ | C20H34O2 | 306.25572 | 307.26303 | Γ-Linolenic acid ethyl ester |

| 17.775 | [M+H-H2O]+ | C33H52O5 | 528.3822 | 529.38953 | Pachymic acid |

| 18.518 | [M+H]+ | C16H30O2 | 254.2246 | 255.23183 | Palmitoleic acid |

| 18.577 | [M+H-H2O]+ | C30H48O3 | 456.36039 | 457.36777 | Ursolic acid |

| 18.601 | [M+H]+ | C18H37NO2 | 299.28224 | 300.28952 | Palmitoylethanolamide |

| 18.962 | [M+H]+ | C21H40O4 | 356.29248 | 357.29977 | Monoolein |

| 19.038 | [M+H-H2O]+ | C30H46O3 | 454.34482 | 455.35299 | Dehydrotrametenolic acid |

| 19.74 | [M+H]+ | C18H35NO | 281.27173 | 282.27899 | Oleamide |

| 20.128 | [M+H]+ | C16H33NO | 255.25618 | 256.26346 | Hexadecanamide |

| 20.812 | [M+H]+ | C20H34O2 | 306.25572 | 307.26303 | Linolenic acid ethyl ester |

| 22.464 | [M+H]+ | C18H37NO | 283.2874 | 284.29468 | Stearamide |

| 23.556 | [M+H]+ | C22H43NO | 337.3344 | 338.34174 | Erucamide |

Table 2.

The compounds identified from GPE by LC-MS-MS in negative model.

| RT (min) | Adducts | Formula | Measured value | Molecular weight | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.769 | [M-H]− | C17H27N3O17P2 | 607.08107 | 606.07379 | UDP-n-Acetylglucosamine |

| 0.943 | [M-H]− | C6H12O7 | 196.05816 | 195.05075 | Gluconic acid |

| 0.945 | [M-H]− | C12H22O11 | 342.11583 | 341.10855 | α,α-Trehalose |

| 0.946 | [M-H]− | C6H12O6 | 180.06327 | 179.05606 | L-Sorbose |

| 0.999 | [M-H]− | C4H6O5 | 134.02147 | 133.01421 | DL-Malic acid |

| 1.113 | [M-H]− | C6H8O7 | 192.02686 | 191.01958 | Citric acid |

| 1.154 | [M-H]− | C4H6O4 | 118.02666 | 117.01942 | Succinic acid |

| 1.358 | [M-H]− | C7H6O5 | 170.02148 | 169.01421 | Gallic acid |

| 1.87 | [2M-H]− | C16H24O11 | 392.13228 | 391.12427 | Shanzhiside |

| 2.756 | [M-H]− | C16H18O9 | 354.0948 | 353.08759 | Neochlorogenic acid |

| 3.056 | [M-H]− | C16H24O10 | 376.13649 | 375.12929 | Mussaenosidic acid |

| 4.441 | [M-H]− | C16H24O10 | 376.13663 | 375.12943 | Loganic acid |

| 4.454 | [M-H]− | C16H18O9 | 354.0948 | 353.08762 | Cryptochlorogenic acid |

| 4.529 | [M-H]− | C9H6O4 | 178.02656 | 177.01924 | Esculetin |

| 4.554 | [M+FA-H]− | C23H34O15 | 550.18934 | 549.18079 | Genipin 1-O-β-D-gentiobioside |

| 4.663 | [M-H]− | C9H8O4 | 180.04225 | 179.03493 | Caffeic acid |

| 4.902 | [M-H]− | C16H18O9 | 354.0948 | 353.08762 | Chlorogenic acid |

| 5.028 | [M+FA-H]− | C17H24O10 | 388.13649 | 387.12878 | Geniposide |

| 5.69 | [M-H]− | C7H8O2 | 124.05246 | 123.04516 | 4-Hydroxybenzyl alcohol |

| 5.734 | [M-H]− | C9H8O3 | 164.04736 | 163.04008 | 3-Coumaric acid |

| 5.847 | [M-H]− | C8H14O4 | 174.08906 | 173.08179 | Suberic acid |

| 6.356 | [M-H]− | C11H12O5 | 224.06829 | 223.06102 | Sinapic acid |

| 6.384 | [M-H]− | C27H30O16 | 610.15473 | 609.14746 | Rutin |

| 6.556 | [M-H]− | C21H20O12 | 464.09505 | 643.08768 | Isoquercitrin |

| 6.729 | [M-H]− | C25H24O12 | 516.12591 | 515.11871 | Isochlorogenic acid B |

| 6.869 | [M-H]− | C27H30O15 | 594.1583 | 593.15118 | Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside |

| 6.884 | [M-H]− | C25H24O12 | 516.12587 | 515.11884 | 3,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid |

| 7.057 | [M-H]− | C21H20O11 | 448.10017 | 447.0929 | Astragalin |

| 7.234 | [M+cl]− | C25H24O12 | 516.12591 | 551.0954 | 4,5-Dicaffeoylquinic |

| 8.104 | [M-H]− | C15H20O4 | 264.13576 | 263.12848 | (±)-Abscisic acid |

| 8.451 | [M-H]− | C15H10O7 | 302.0424 | 301.03513 | Morin |

| 8.516 | [M-H]− | C15H10O6 | 286.04741 | 285.04013 | Luteolin |

| 10.273 | [M-H]− | C12H14O4 | 222.0889 | 221.08162 | Monobutyl phthalate |

| 11.813 | [M-H]− | C16H12O5 | 284.06801 | 283.06064 | Acacetin |

| 12.754 | [M-H]− | C18H34O4 | 314.24519 | 313.23782 | (+/-)12(13)-Dihome |

| 15.249 | [M-H]− | C31H46O5 | 498.33362 | 497.32639 | Poricoic acid A |

| 17.272 | [M-H]− | C32H50O5 | 514.36476 | 513.35754 | 3-O-Acetyl-1α-hydroxytrametenolic acid, pachymic acid |

| 17.806 | [M-H]− | C33H52O5 | 528.38028 | 527.37286 | Oleic acid alkyne |

| 17.917 | [M-H]− | C18H30O2 | 278.2242 | 277.21689 | Ursolic acid |

| 18.595 | [M-H]− | C30H48O3 | 456.3596 | 455.35211 | Ursolic acid |

Table 3.

Effective ingredients in GPE.

| MOL ID | Compound name | Source | Target no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOL000273 | 16α-Hydroxydehydrotrametenolic acid | P. cocos | 2 |

| MOL000275 | Trametenolic acid | P. cocos | 1 |

| MOL000276 | 7,9(11)-Dehydropachymic acid | P. cocos | 0 |

| MOL000279 | Cerevisterol | P. cocos | 1 |

| MOL000280 | (2R)-2-[(3S,5R,10S,13R,14R,16R,17R)-3,16-Dihydroxy-4,4,10,13,14-pentamethyl-2,3,5,6,12,15,16,17-octahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-17-yl]-5-isopropyl-hex-5-enoic acid | P. cocos | 0 |

| MOL000282 | Ergosta-7,22E-dien-3beta-ol | P. cocos | 1 |

| MOL000283 | Ergosterol peroxide | P. cocos | 1 |

| MOL000285 | (2R)-2-[(5R,10S,13R,14R,16R,17R)-16-Hydroxy-3-keto-4,4,10,13,14-pentamethyl-1,2,5,6,12,15,16,17-octahydrocyclopenta[a]phenanthren-17-yl]-5-isopropyl-hex-5-enoic acid | P. cocos | 0 |

| MOL000287 | Eburicoic acid | P. cocos | 0 |

| MOL000289 | Poricoic acid | P. cocos | 0 |

| MOL000290 | Poricoic acid A | P. cocos | 0 |

| MOL000291 | Poricoic acid B | P. cocos | 0 |

| MOL000292 | Poricoic acid C | P. cocos | 0 |

| MOL000296 | Hederagenin | P. cocos | 23 |

| MOL000300 | Dehydroeburicoic acid | P. cocos | 0 |

| MOL001406 | Crocetin | G. jasminoides | 14 |

| MOL001663 | 3-Epioleanolic acid | G. jasminoides | 0 |

| MOL001941 | Ammidin | G. jasminoides | 8 |

| MOL004561 | Sudan III | G. jasminoides | 13 |

| MOL000098 | Quercetin | G. jasminoides | 153 |

| MOL000358 | Beta-sitosterol | G. jasminoides | 37 |

| MOL000422 | Kaempferol | G. jasminoides | 72 |

| MOL000449 | Stigmasterol | G. jasminoides | 34 |

| MOL001494 | Mandenol | G. jasminoides | 3 |

| MOL001506 | Supraene | G. jasminoides | 0 |

| MOL001942 | Isoimperatorin | G. jasminoides | 1 |

| MOL002883 | Ethyl oleate (NF) | G. jasminoides | 1 |

| MOL003095 | 5-Hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)chromone | G. jasminoides | 26 |

| MOL007245 | 3-Methylkempferol | G. jasminoides | 11 |

| MOL009038 | GBGB | G. jasminoides | 0 |

3.2. Intersection Analysis of the Effective Ingredient Targets of GPE and the Targets of HUA

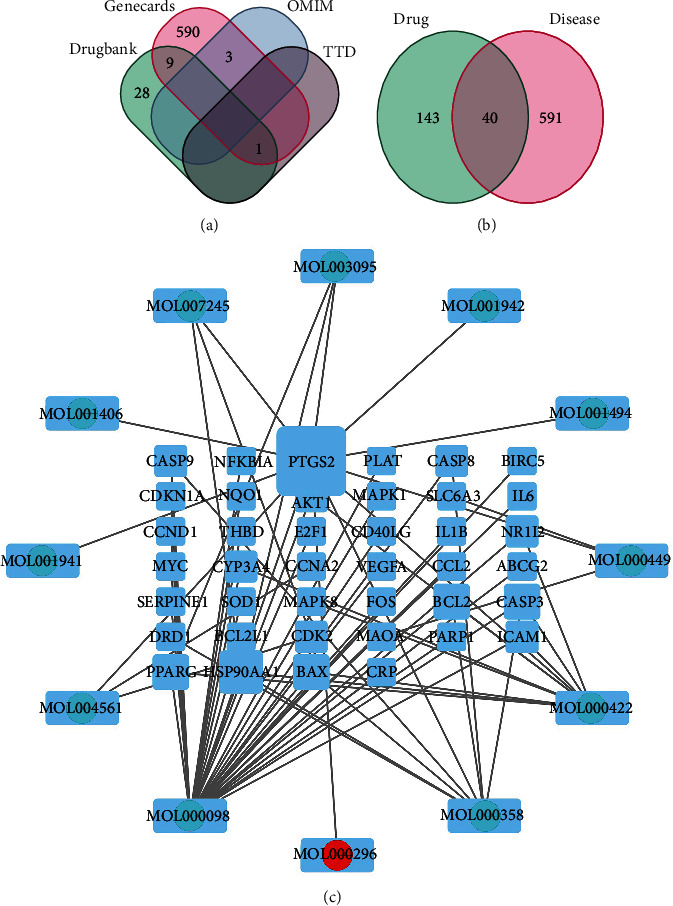

The 631 hyperuricemia-related targets were searched (Figure 1(a)) from GeneCards, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), PharmGkb, TTD, DrugBank, and other databases. There were 183 targets of GPE intersected with the disease targets, and 40 common targets of GPE and HUA were mapped as the Venn diagram (in Figure 1(b)).

Figure 1.

(a) HUA disease targets; (b) intersection of active component targets of GPE and hyperuricemic acid target; (c) regulation network of active components of GPE.

3.3. GPE Effective Ingredient-Disease Target Regulatory Network

Twelve effective ingredients and 40 related targets of GPE were introduced into Cytoscape 3.7.0 to obtain the “effective ingredient-target” regulatory network diagram (Figure 1(c)). In Figure 1(c), there were 52 nodes (12 ingredients, 40 targets) and 70 edges; round nodes represent active ingredients, square nodes represent corresponding targets, and black edges represent the relationship between active ingredients and HUA targets. The results showed that 58.3% (7) of the effective ingredients in GPE could act on multiple gene targets. Among them, quercetin, kaempferol, β-sitosterol, and hederagenin had many targets and played the important role in the regulation process. The same target could also be regulated by multiple effective ingredients. Thirteen targets (32.5%) were corresponding to more than two effective ingredients, indicating the complex and diverse action mechanism characteristics of GPE components.

3.4. Results of Core Target Screening and PPI Network Construction

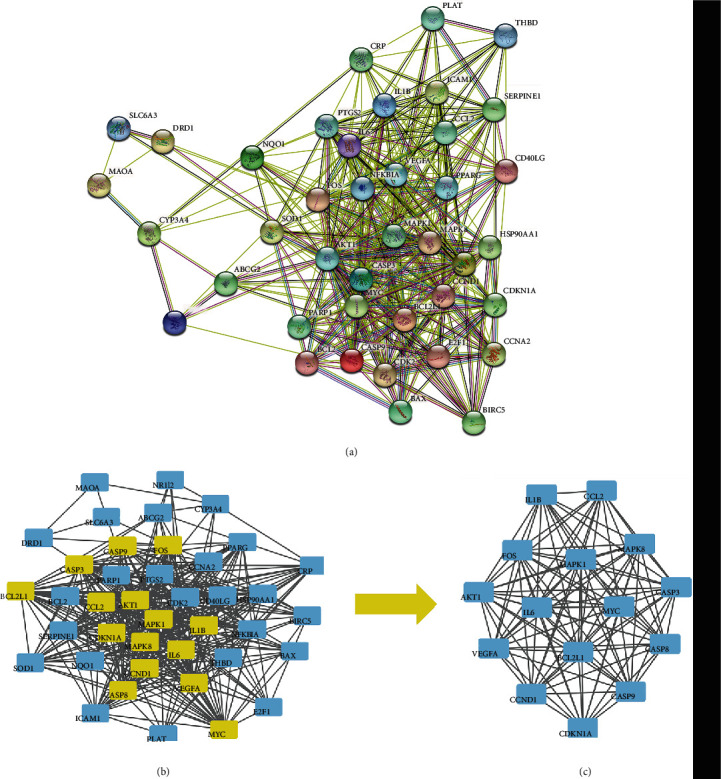

The intersection target was imported into the STRING database, and the species was set as “Homo sapiens” to analyze protein interaction (Figure 2(a)). The relevant files were imported into the Cytoscape software to build a PPI network diagram; one node represented one target, and the TCMSP edge represented the target. We click on the interaction relationship and finally get the protein interaction network analysis diagram (Figure 2(a)). The network contained 15 key gene targets, i.e., IL-1B, IL-6, MAPK1, MAPK8, AKT1, MYC, VEGFA, CASP3, CASP8, CASP9, BCL2L1, FOS, CCND1, CDKN1A, and CCL2, which were the components of the core network (Figures 2(b) and 2(c)).

Figure 2.

PPI protein interaction network of GPE in treatment of HUA targets (a) and CytoNCA Core Network Analysis (b, c).

3.5. The Results of GO Function Enrichment Analysis

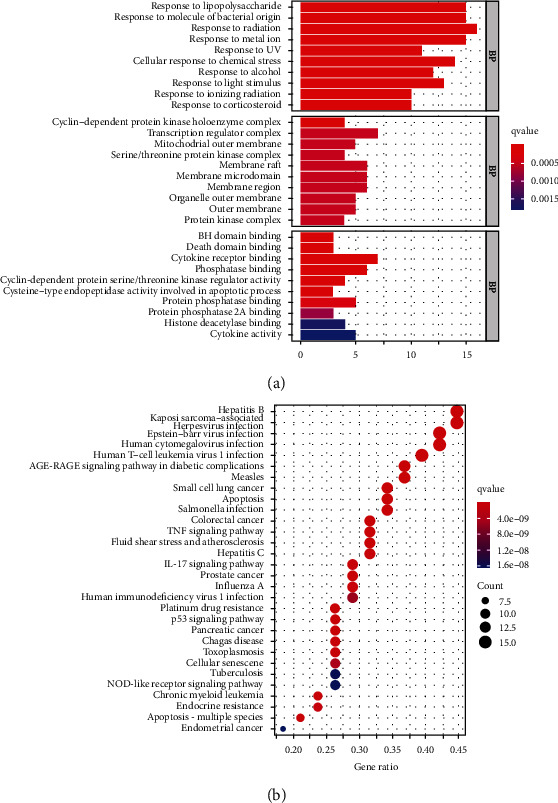

GO describes the biological process (BP) of gene products (protein or RNA), molecular function (MF), and cellular component (CC) and organizes the functional concepts with different thicknesses into atlases for analysis and sorting according to P value (Figure 3(a)). In Figure 3(a), the abscissa represents the number of enriched genes and the color of the bar represents the size of the P value. When the color changed from blue to red, the P value changed to small. The process was mainly concentrated in the biological process, and there were 1591 enrichment results which were mainly involved in the reaction of oxidative stress, lipids, bacteria-derived molecules, and chemical substances. In molecular functions, there were 57 results which were related to cell death, cytokine receptors, and other enzyme activities. There were 27 enriched results for cell composition, which had the relationship with the cyclin-dependent protein kinase holoenzyme complex, transcription regulation complex, and mitochondrial outer membrane.

Figure 3.

GO biological function enrichment bar chart (a) and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis bubble diagram (b).

3.6. The Results of KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis

The corresponding target protein of GPE was mapped to the pathway by KEGG to analyze the activity, target, and pathway of drug. The signaling pathways mainly included the inflammatory signaling pathways of TNF and IL-7, apoptosis, tumors such as small cell lung cancer, and AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications. There were 139 pathways by the KEGG enrichment pathway analysis, and the top 20 pathways are shown in Figure 3(b).

3.7. Docking Prediction of Effective Ingredients and Core Target Molecules

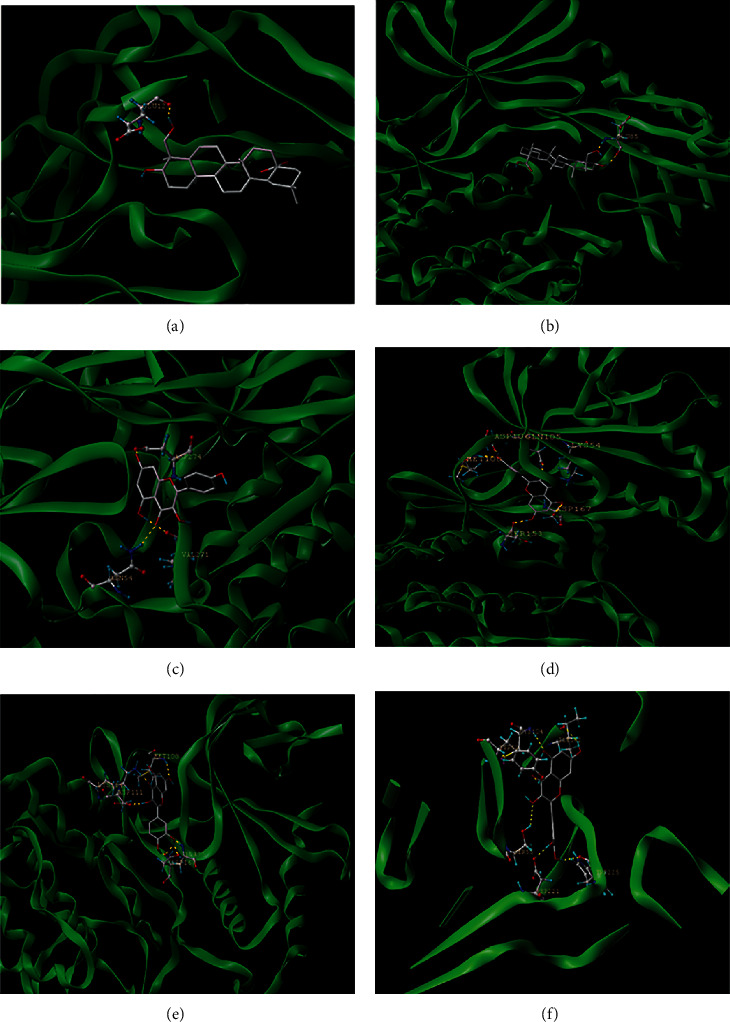

The core targets of IL-6, AKT1, MYC, VEGFA, and MAPK1 protein with higher node degree values and the best effective ingredients, quercetin, kaempferol, and hederagenin, in GPE were selected for molecular docking in the PPI protein interaction network (Table 4, Figure 4).

Table 4.

Binding energy of effective ingredients in GPE with potential HUA targets.

| Compounds | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKT1 | VEGFA | MAPK1 | IL-6 | |

| Quercetin | -8.1 | -6.9 | -9.1 | -9.4 |

| Kaempferol | -8.1 | -5.5 | -7.5 | -5.9 |

| Hederagenin | -6.5 | -7 | ||

Figure 4.

Molecular binding map of effective ingredients in GPE with HUA potential target: (a) hederagenin AKT1; (b) hederagenin VEGFA; (c) kaempferol AKT1; (d) kaempferol MAPK1; (e) quercetin IL-6; (f) quercetin MAPK1.

3.8. Verification of Animal Experiment

3.8.1. Effects on Plasma Uric Acid Levels of Hyperuricemic Rats

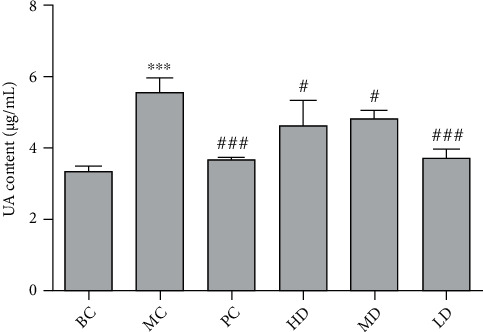

In Table 5 and Figure 5, the levels of uric acid in the model group were significantly increased compared with the blank group (P < 0.001), which indicated that the hyperuricemic rat model was established. Compared with the MC, GPE-HD, GPE-MD, and GPE-LD could effectively reduce the levels of uric acid (P < 0.05). GPE-LD showed significant difference (P < 0.001), and there was no significant difference compared with the PC (P > 0.05).

Table 5.

Effect of GPE on plasma uric acid levels in hyperuricemic rats (μg/mL, ) (n = 6).

| Groups | UA |

|---|---|

| BC | 3.37 ± 0.14 |

| MC | 5.56 ± 0.41∗∗∗ |

| PC | 3.69 ± 0.06### |

| GPE-HD | 4.64 ± 0.70# |

| GPE-MD | 4.83 ± 0.25# |

| GPE-LD | 3.70 ± 0.28### |

Note: compared with BC, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001; compared with MC, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Effect of GPE on UA levels in hyperuricemic rats. Compared with BC, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001; compared with MC, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001.

3.8.2. Effect on Antioxidative Stress Ability of Hyperuricemic Rats

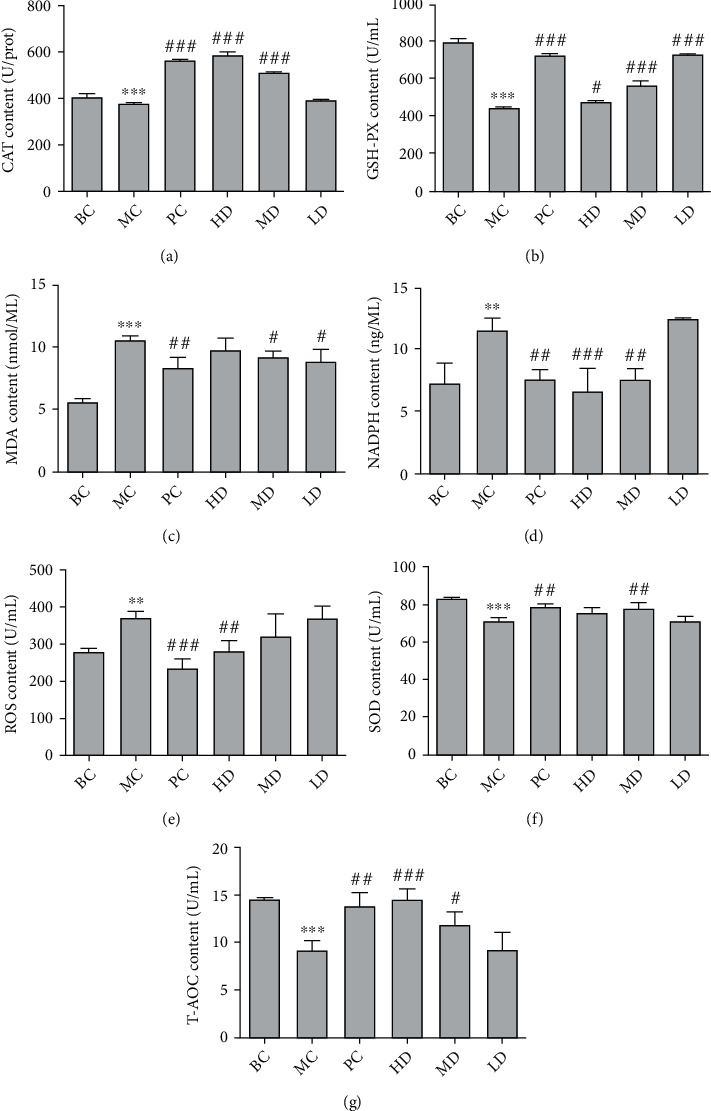

In Figures 6(b), 6(f), and 6(g), compared with BC, the contents of GSH-PX, T-AOC, and SOD in the plasma of MC were significantly decreased (P < 0.001), and the contents of CAT in the liver homogenate were significantly decreased (P < 0.001). In Figures 6(a), 6(c), 6(d), and 6(e), compared with BC, the contents of ROS, MDA, and NADPH in the plasma of MC were significantly increased (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, and P < 0.01, respectively); compared with MC, the levels of GSH-PX, T-AOC, and SOD in plasma of GPE-HD, GPE-MD, and GPE-LD were significantly increased (P < 0.05), and the contents of CAT in the liver homogenate of rats were significantly increased (P < 0.05). The contents of ROS, MDA, and NADPH in the plasma of GPE-HD, GPE-MD, and GPE-LD were significantly decreased (P < 0.05), indicating that GPE could improve oxidative stress produced by hyperuricemia.

Figure 6.

Effect of GPE on the levels of CAT (a), GSH-PX (b), MDA (c), NADPH (d), ROS (e), SOD (f), and T-AOC (g) in hyperuricemic rats. Compared with BC, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001; compared with MC, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001.

3.8.3. Effect on Liver and Kidney Function in Hyperuricemic Rats

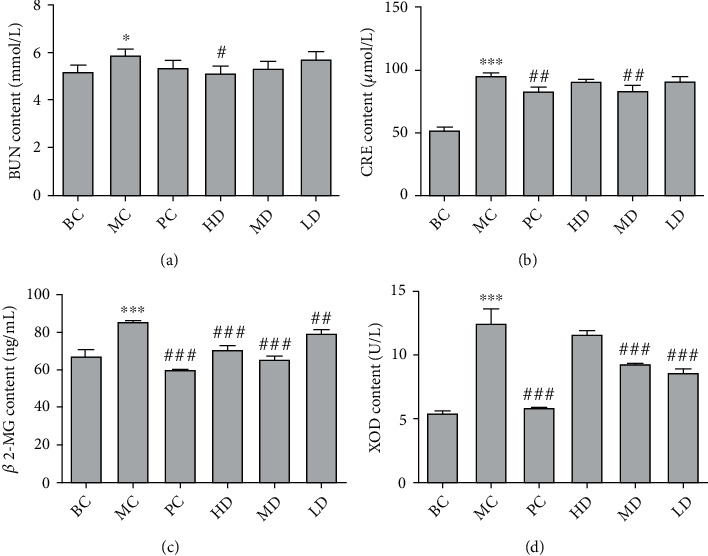

In Figure 7, compared with the BC, the contents of BUN, CRE, β2-MG, and XOD in the MC were significantly increased (P < 0.05); compared with the MC, the GPE-HD, GPE-MD, and GPE-LD could significantly reduce the BUN, CRE, β2-MG, and XOD in the plasma of rats (P < 0.05). Among them, the contents of β2-MG in the plasma of rats in the GPE-MD and GPE-HD were extremely significantly decreased (P < 0.001). It indicated that GPE could reduce uric acid in the plasma of hyperuricemic rats by reducing XOD activity and could improve liver and kidney damage produced by HUA.

Figure 7.

Effects of GPE on BUN (a), CRE (b), β2-MG (c), and XOD (d) levels in hyperuricemic rats. Compared with BC, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001; compared with MC, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001.

3.8.4. Determination of Inflammatory Factors in Rat Plasma

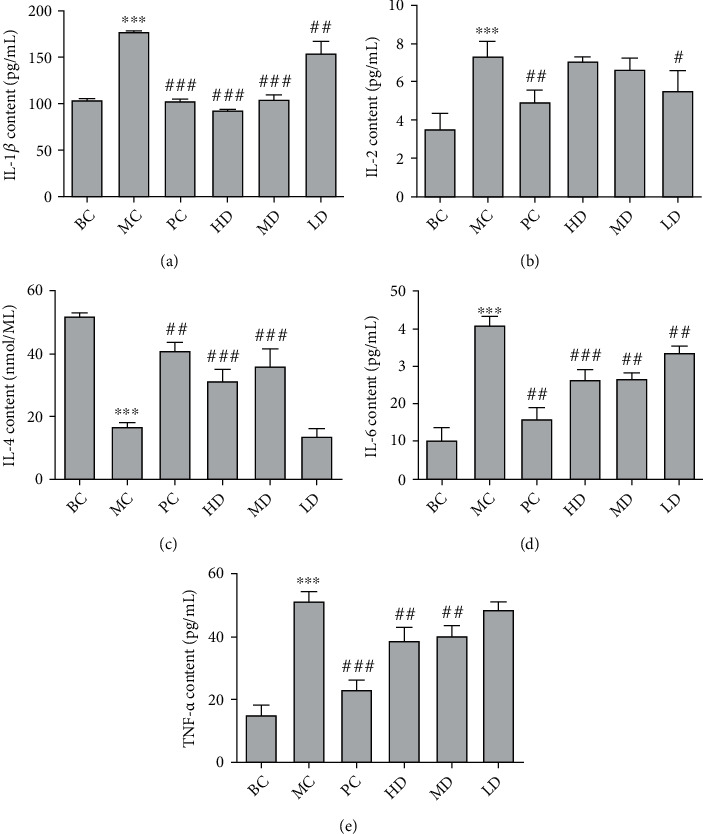

In Figure 8, the expression levels of IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, and TNF-α in the plasma in the MC were significantly increased compared with the BC (P < 0.001). The contents of IL-2, IL-6, and TNF-α in the plasma of the GPE-HD, GPE-MD, and GPE-LD were significantly decreased compared with those of the MC (P < 0.05), and the contents of IL-1β and IL-6 in the GPE-MD and GPE-HD were significantly decreased (P < 0.001). The contents of IL-4 in the plasma in the MC were significantly decreased compared with the those in the BC (P < 0.001). Compared with the MC, the IL-4 content in the plasma of the GPE-HD, GPE-MD, and GPE-LD was significantly increased (P < 0.001). The results showed that the GPE could improve the inflammatory level of hyperuricemia and also had an anti-inflammatory effect.

Figure 8.

Effect of GPE on the contents of IL-1β (a), IL-2 (b), IL-4 (c), IL-6 (d), and TNF-α (e) levels in hyperuricemic rats. Compared with BC, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001; compared with MC, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001.

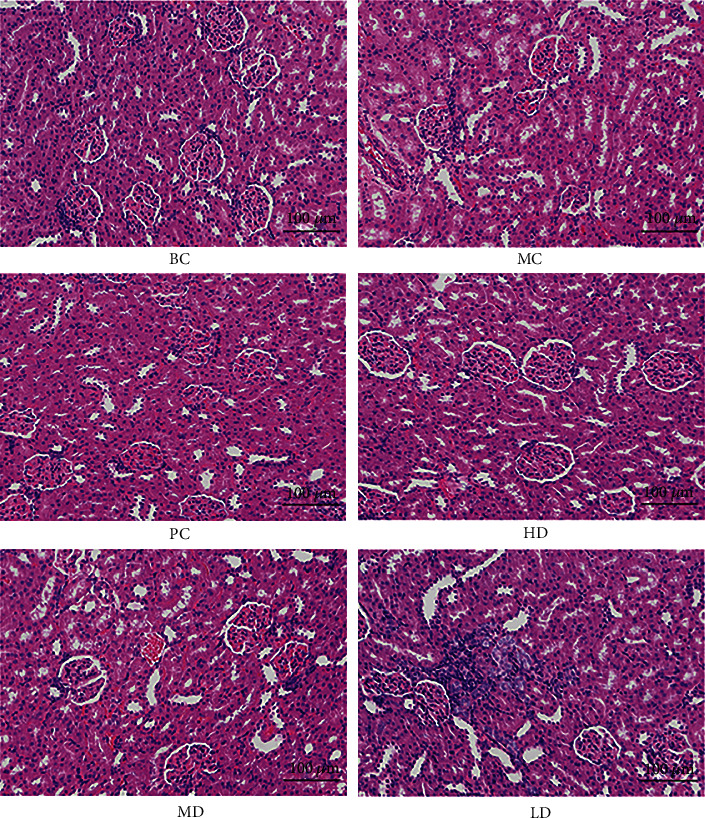

3.8.5. Pathological Changes of Renal Tissue in Rats

In Figure 9, the renal structure of BC was normal without inflammatory cell infiltration. In the MC group of rats, there were disorganized renal tubules, inflammatory factor infiltration in renal interstitial part, renal cortical edema, massive accumulation of lymphocytes, and inflammatory cell infiltration around glomeruli. The number of lymphocytes was relatively reduced in LD compared with MC, but there was still inflammatory cell infiltration, and tubular arrangement was scattered, which was not significant in GPE-MD compared with MC. The glomerular morphological structure of GPE-HD was basically normal with regular tubular arrangement.

Figure 9.

Pathological section of kidney tissue of hyperuricemic rats (200x).

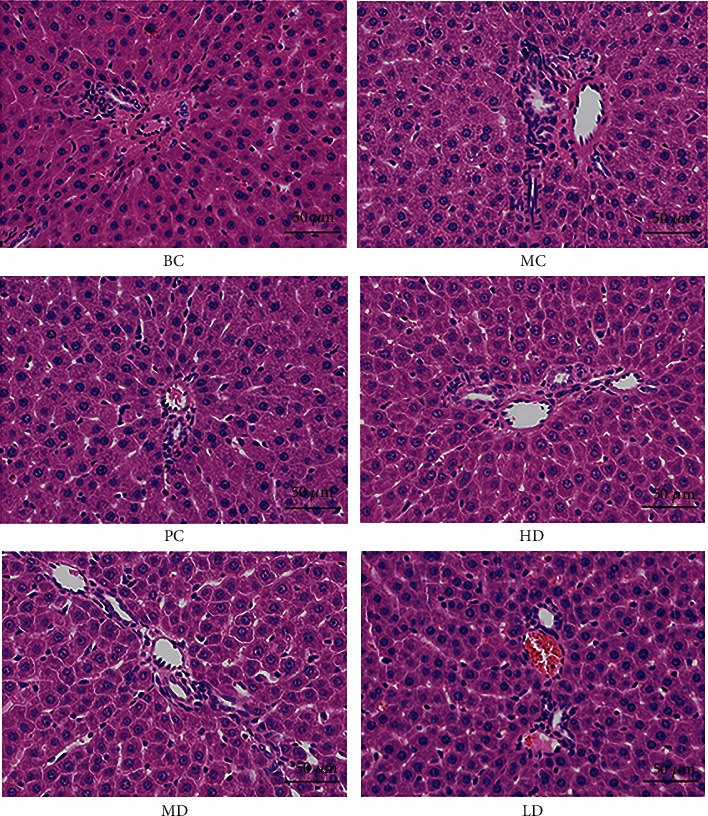

3.8.6. Pathological Changes of Liver Tissue in Rats

In Figure 10, compared with BC, the hepatocytes of rats in MC were significantly swollen, tiny round fat vacuoles were observed in the cytoplasm, and the swelling of hepatocytes was alleviated to varying degrees in each group without other obvious abnormalities. The swelling of hepatocytes was most significantly alleviated in LD, indicating that GPE could protect the liver from damage.

Figure 10.

Histopathological section of liver tissue in hyperuricemic rats (400x).

4. Discussion

In recent years, the incidence of gout has increased exponentially. There are two main reasons for excessive uric acid in the body: (i) the excessive production of UA due to abnormal activity of XOD or excessive intake of exogenous purines and (ii) the accumulation of UA in the body due to the decrease of UA excretion [18]. Despite the current drugs that inhibit XOD having a good effect on reducing UA, there are severe adverse reactions such as renal injury and myelosuppression [19]. Gardenia has the effect of purging fire and removing annoyance, clearing heat and dampness, and cooling blood and detoxification. Besides, it is often used in diseases such as fever, swelling and pain, astringent pain of gonorrhea, and hematemesis. Poria cocos has the effects of promoting diuresis and dampness, invigorating the spleen, and calming the heart [20]. Thus, this study discussed the potential mechanism of GPE in the treatment of HUA based on network pharmacology to understand the pharmacological mechanism of GPE.

Forty core targets of GPE in the treatment of HUA were screened in this study. Further analysis of the compound-disease-target regulatory network showed that quercetin, β-sitosterol, kaempferol, hederagenin, and other active ingredients could act on multiple targets in the network. Besides, the same target could also be regulated by multiple effective ingredients. Thirteen targets (32.5%) corresponded to more than two effective ingredients, indicating that there was the complex composition of GPE and the action mechanism of various targets. Quercetin can inhibit monosodium urate- (MSU-) induced mechanical hyperalgesia, leukocyte recruitment, the production of TNF-α and IL-1β, the production of superoxide anion, the activation of inflammatory reaction, the decrease of antioxidant level, the activation of NF-κB, and the expression of the inflammatory component mRNA [21]. β-Sitosterol can improve nephrotoxicity and kidney disease and adjust the activity of NRF-2 antioxidant enzymes to reduce nephrotoxic mouse creatinine and the expression of uric acid, urea, and iNOS to normal levels, and excessive peroxides and internal and external toxicants in the body are eliminated [22]. Hederagenin has antibacterial and anti-inflammatory pharmacological effects, and previous studies have shown that hederagenin can block the NF-κB signaling pathway to reduce the release of inflammatory factors such as IL-6, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and NO [23]. Some studies have shown that kaempferol may be a potential XOD inhibitor, because it can block the entry of the substrate by inserting the hydrophobic active site of XOD and inhibiting the activity of XOD by competing sites. Moreover, it can reduce the level of serum UA in hyperuricemia rat [24, 25]. PPI network also confirmed that there was a close relationship between GPE and HUA targets, and the results were reliable and of great reference value.

It is preliminarily predicted that GPE plays a role in the treatment of HUA through cell death, cytokine receptor and other enzyme activity pathways, TNF signal pathway, IL-7 signal pathway, and others through the GO functional enrichment analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the core targets. During the pathological process of HUA, UA is an important endogenous antioxidant [26]. Under normal circumstances, the ROS generated are neutralized by the endogenous antioxidants, and there is an equilibrium between the ROS generated and the antioxidants present, but the continuous increase of the UA level will enhance the oxidative stress reaction in vivo [27]. The increase of the UA level in the blood can destroy the oxidation-reduction balance of the body through various ways, enabling the body to produce a mass of reactive oxygen species (ROS), damaging tissue cells, thus reducing the antioxidant capacity of the body and at last leading to the occurrence of oxidative stress damage [28–30]. NADPH oxidases (Nox) are one of many sources of ROS. Its catalytic product ROS participates in body defense and information transmission. The high level of ROS caused by excessive activation of NADPH will lead to tissue inflammation and further pathological damage of tissues and organs [31]. NADPH oxidase and its ROS products play a key role in the occurrence and development of acute kidney injury [32, 33]. The body scavenges reactive oxygen radicals through active enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), and peroxidase GSH-Px, thus reducing cell damage [34, 35]. Studies have shown that TNF-α can induce oxidative stress and inflammation. Besides, the increase of ROS production mainly comes from the intracellular NADPH oxidase pathway. TNF-α increases the level of oxidative stress mainly by upregulating the expression of NOX2 and its related subunits [36, 37]. IL-7 is a multifunctional cytokine, which can act on a variety of cells. The main function is to promote the development, antiapoptosis, and proliferation of immature B and T cells and to participate in the differentiation and maturation of thymocytes [38, 39]. The biological effect of IL-7 is mainly achieved through the binding of IL-7 to the IL-7 receptor (IL-7R). IL-7 activates the IL-7R signal pathway, upregulates the antiapoptotic protein, inhibits differentiated and activated T cell apoptosis, and downregulates the proapoptotic protein to prevent T cell apoptosis after binding to IL-7R. IL-7 has a strong immunomodulatory effect. As a consequence, IL-7 plays an important role in maintaining the homeostasis of immune function in vivo [40, 41].

High uric acid environment can cause oxidative stress, which is closely related to inflammation. Oxidative stress will promote the expression of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-6 [42]. At the same time, inflammatory cells generate more reactive oxygen species after activation, resulting in an increase of oxidative stress level after inflammatory lesions. Another major cause of the creation of hyperuricemia is the reduction of uric acid excretion. Around 70% of uric acid in the body is excreted by the kidney. Uric acid is finally excreted with urine in the form of urate after glomerular filtration, renal tubular reabsorption, renal tubular secretion, and reabsorption after secretion [43]. β2-Microglobulin (β2-MG) is a small molecule globulin produced by lymphocytes, platelets and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The excretion of β2-MG is extremely low under normal conditions, but its excretion increases when renal tubules are damaged or filtration function of glomerular decreases [44, 45]. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) is one of the indicators of renal function, and it is the final product of human protein metabolism. When glomerular filtration ability decreased to a certain degree, BUN level tends to increase [46]. Serum creatinine (SCr) is an endogenous creatinine filtered by glomerulus. Like BUN, the change of SCr content is also an important indicator of renal function [47]. When renal function is damaged, the level of SCr will increase [48]. In the clinic, the degree of renal function injury of patients is often judged by the detection of SCr index. Some studies have shown that hyperuricemia can damage rats' kidneys through inflammatory reaction and the oxidative stress pathway [49–51].

The model of hyperuricemia rats was established to demonstrate the results of network pharmacological analysis. The results showed that compared with the model group, the GPE group could significantly increase the activities of SOD, CAT, GSH-Px, and T-AOC in the plasma and liver tissue and decrease the levels of ROS, MDA, and NADPH in the plasma. It is suggested that GPE has the effect of antioxidant stress. The secretion of IL-4 was significantly increased after treatment with GPE. However, the contents of IL-6, IL-2, IL-1β, and TNF-α in the renal tissue of hyperuricemia rats were significantly decreased, indicating that GPE can enhance the secretion of IL-4 in hyperuricemia rats and reduce the inflammatory level of hyperuricemia rats, which has a certain anti-inflammatory effect. Compared with the blank group, the levels of β2-MG, BUN, and SCr in the model group were significantly higher, indicating that the kidney of hyperuricemia rats was damaged. The sections of rat renal tissue in the model group showed that the renal tubules were messy, and the renal interstitium was infiltrated with inflammatory factors. It also indicated that the kidney in the model group was damaged, which led to the decline of renal function in hyperuricemia rats. These renal injuries can reduce the renal excretion of UA, thus increasing the level of uric acid in the body. Compared with the model group, the levels of β2-MG, BUN, and Cr in the GPE group decreased significantly, indicating that the GPE can protect and improve renal function. It is speculated that GPE promotes the excretion of UA by improving the renal function damage caused by oxidative stress, thus reducing the level of UA. Besides, it can inhibit inflammatory reaction and antioxidant stress in order to achieve the purpose of treatment. Generally speaking, GPE has the characteristics of multicomponents, multitargets, and multipathways in the treatment of HUA. It mainly plays a role in controlling the development of HUA through cell death, cytokine receptor, and other enzyme activity pathways, such as TNF α, IL-7, and other signaling pathways. Further animal experiments confirmed that GPE can reduce the level of oxidative stress in HUA model rats. In addition, regulating the expression of inflammatory factors such as TNF-α in renal tissue may be one of its mechanisms.

5. Conclusion

GPE has the characteristics of multicomponents, multitargets, and multipathways in the treatment of HUA. It mainly plays a role in controlling the development of HUA through cell death, cytokine receptor, and other enzyme activity pathways, such as TNF-α and IL-7 signaling pathways. Further animal experiments confirmed that GPE can reduce the level of oxidative stress in HUA model rats. In addition, regulating the expression of inflammatory factors such as TNF-α in renal tissue may be one of its mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Major Public Welfare Projects in Henan Province (201300110200); Research on Precision Nutrition and Health Food, Department of Science and Technology of Henan Province (CXJD2021006); and the Key Project in Science and Technology Agency of Henan Province (212102110336 and 202102110136).

Contributor Information

Jinmei Wang, Email: wangjinmeiscp@126.com.

Yan Zhang, Email: snowwinglv@126.com.

Wenyi Kang, Email: kangweny@hotmail.com.

Data Availability

The [data type] data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Ethical Approval

We confirm that all methods used in this study were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Additionally, all experimental protocols were approved by Henan University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Lijun Liu, Shengjun Jiang, Xuqiang, and Liu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Yu Y. R., Liu Q. P., Li H. C., Wen C. P., He Z. X. Alterations of the gut microbiome associated with the treatment of hyperuricaemia in male rats. Frontiers in Microbiology . 2018;9:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang G. Y., Nie Y. C., Chang Y. B., et al. Protective effects of _Rhizoma smilacis glabrae_ extracts on potassium oxonate- and monosodium urate-induced hyperuricemia and gout in mice. Phytomedicine . 2019;59:p. 152772. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ota-Kontani A., Hirata H., Ogura M., Tsuchiya Y., Harada-Shiba M. Comprehensive analysis of mechanism underlying hypouricemic effect of glucosyl hesperidin. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications . 2020;521(4):861–867. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.10.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song C., Zhao X. Uric acid promotes oxidative stress and enhances vascular endothelial cell apoptosis in rats with middle cerebral artery occlusion. Bioscience Reports . 2018;38(3):1–9. doi: 10.1042/BSR20170939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurajoh M., Fukumoto S., Yoshida S., et al. Uric acid shown to contribute to increased oxidative stress level independent of xanthine oxidoreductase activity in MedCity21 health examination registry. Scientific Reports . 2021;11(1):p. 7378. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86962-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batandier C., Poyot T., Marissal-Arvy N., et al. Acute emotional stress and high fat/high fructose diet modulate brain oxidative damage through NrF2 and uric acid in rats. Nutrition Research . 2020;79(1):23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J., Yang Z. H., Zhang S. S., et al. Investigation of endogenous malondialdehyde through fluorescent probe MDA-6 during oxidative stress. Analytica Chimica Acta . 2020;1116:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2020.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J., Zhou L., Cui L., Liu Z., Wei J., Kang W. Antioxidant and _α_ -glucosidase inhibitiory activity of _Cercis chinensis_ flowers. Food Science and Human Wellness . 2020;9(4):313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2020.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehnati P., Baradaran B., Vahidian F., Nadiriazam S. Functional response difference between diabetic/normal cancerous patients to inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stresses after radiotherapy. Reports of Practical Oncology and Radiotherapy . 2020;25(5):730–737. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miricescu D., Totan A., Stefani C., et al. Hyperuricemia, endothelial dysfunction and hypertension. Romanian Journal of Medical Practice . 2020;15(2):178–182. doi: 10.37897/RJMP.2020.2.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Q. X., Wang Q. L., Deng W. W., et al. Anti-hyperuricemic and anti-gouty arthritis activities of polysaccharide purified from _Lonicera japonica_ in model rats. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules . 2019;123:801–809. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogino K., Kinugasa Y., Kato M., Yamamoto K., Hamada T., Hisatome I. Uric-acid lowering treatment by a xanthine oxidase inhibitor improved the diastolic function in patients with hyperuricemia. Journal of Cardiac Failure . 2019;25(8):p. S26. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2019.07.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shan M. Q., Wang T. J., Jiang Y. L., et al. Comparative analysis of sixteen active compounds and antioxidant and anti- influenza properties of _Gardenia jasminoides_ fruits at different times and application to the determination of the appropriate harvest period with hierarchical cluster analysis. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2019;233(233):169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Y. J., Li S., Li H. X., et al. Effect of a polysaccharide from _Poria cocos_ on humoral response in mice immunized by H1N1 influenza and HBsAg vaccines. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules . 2016;91:248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng L. J., Yan J. X., Wang P., Zhou Y., Wu X. A. Effects of Pachman on the expression of renal tubular transporters rURAT1, rOAT1 and r OCT2 of the rats with hyperuricemia. Western Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine . 2019;32(6):10–14. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu J. X., Zeng J. X., Luo G. M., Zhu Y. Y., Wang X. Y., Wu B. Study on effective part of anti-hyperuricemia in Gardeniae fructus. Chinese Journal of Experimental Traditional Medical Formulae . 2012;18(14):p. 159. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang F., Wang H. L., Feng G. Q., Zhang S. L., Wang J. M., Cui L. L. Rapid identification of chemical constituents in Hericium erinaceus based on LC-MS/MS metabolomics. Journal of Food Quality . 2021;2021:10. doi: 10.1155/2021/5560626.5560626 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong Q., Wang L. Y., Huang Z. Y., et al. High concentrations of uric acid and angiotensin II act additively to produce endothelial injury. Mediators of Inflammation . 2020;2020:11. doi: 10.1155/2020/8387654.8387654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Era B., Delogu G. L., Pintus F., et al. Looking for new xanthine oxidase inhibitors: 3-Phenylcoumarins _versus_ 2-phenylbenzofurans. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules . 2020;162:774–780. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.06.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang P. F., Hua T., Wang D., Zhao Z. W., Xi G. L., Chen Z. F. Phytochemical and chemotaxonomic study of _Poria cocos_ (Schw.) Wolf. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology . 2019;83:54–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bse.2019.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruiz-Miyazawa K. W., Staurengo-Ferrari L., Mizokami S. S., et al. Quercetin inhibits gout arthritis in mice: induction of an opioid-dependent regulation of inflammasome. Inflammopharmacology . 2017;25(5):555–570. doi: 10.1007/s10787-017-0356-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharmila R., Sindhu G., Arockianathan P. M. Nephroprotective effect of β-sitosterol on N-diethylnitrosamine initiated and ferric nitrilotriacetate promoted acute nephrotoxicity in Wistar rats. Journal of Basic and Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology . 2016;27(5):473–482. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp-2015-0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang G., Tang H., Zhang Y., Xiao X., Xia Y., Ai L. The intervention effects of _Lactobacillus casei_ LC2W on _Escherichia coli_ O157:H7 -induced mouse colitis. Food Science and Human Wellness . 2020;9(3):289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2020.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song S. H., Park D. H., Bae M. S., et al. Ethanol extract of Cudrania tricuspidata leaf ameliorates hyperuricemia in mice via inhibition of hepatic and serum xanthine oxidase activity. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2018;2018:9. doi: 10.1155/2018/8037925.8037925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Z., Xue Y., Wang N., et al. High uric acid model in Caenorhabditis elegans. Food Science and Human Wellness . 2019;8(1):63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2019.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirończuk-Chodakowska I., Witkowska A. M., Zujko M. E. Endogenous non-enzymatic antioxidants in the human body. Advances in Medical Sciences . 2017;63:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdel-Daim M. M., Abuzead S. M. M., Halawa S. M. Protective role of Spirulina platensis against acute deltamethrin-induced toxicity in rats. PLoS One . 2013;8(9):1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdel-Daim M. M. Synergistic protective role of ceftriaxone and ascorbic acid against subacute diazinon-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Cytotechnology . 2016;68(2):279–289. doi: 10.1007/s10616-014-9779-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdou R. H., Abdel-Daim M. M. Alpha-lipoic acid improves acute deltamethrin-induced toxicity in rats. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology . 2014;92(9):773–779. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2014-0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang L. J., Chang B. C., Guo Y. L., Wu X. P., Liu L. The role of oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis in the pathogenesis of uric acid nephropathy. Renal Failure . 2019;41(1):616–622. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2019.1633350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdelkhalek N. K. M., Ghazy E. W., Abdel-Daim M. M. Pharmacodynamic interaction of Spirulina platensis and deltamethrin in freshwater fish Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus: impact on lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International . 2015;22(4):3023–3031. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovacevic S., Ivanov M., Miloradovic Z., et al. Hyperbaric oxygen preconditioning and the role of NADPH oxidase inhibition in postischemic acute kidney injury induced in spontaneously hypertensive rats. PLoS One . 2020;15(1, article e0226974) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeong B. Y., Lee H. Y., Park C. G., et al. Oxidative stress caused by activation of NADPH oxidase 4 promotes contrast-induced acute kidney injury. PLoS One . 2018;13(1):1–22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun X., Xu Z., Wang Y., Liu N. Protective effects of blueberry anthocyanin extracts on hippocampal neuron damage induced by extremely low-frequency electromagnetic field. Food Science and Human Wellness . 2020;9(3):264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2020.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu X., Jiang C., Chen Y., Shi F., Lai C., Shen L. Major royal jelly proteins accelerate onset of puberty and promote ovarian follicular development in immature female mice. Food Science and Human Wellness . 2020;9(4):338–345. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2020.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maryam N., Sina M., Esmaeel B., et al. Ameliorative effects of histidine on oxidative stress, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and renal histological alterations in streptozotocin/nicotinamide-induced type 2 diabetic rats. Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences . 2020;6(23):1–10. doi: 10.22038/ijbms.2020.38553.9148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X., Zhang F. L., Zhou H. L., et al. Interplay of TNF-α, soluble TNF receptors and oxidative stress in coronary chronic total occlusion of the oldest patients with coronary heart disease. Cytokine . 2020;125:p. 154836. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2019.154836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coppola C., Hopkins B., Huhn S., du Z., Huang Z. Y., Kelly W. J. Investigation of the impact from IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15 on the growth and signaling of activated CD4+ T cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2020;21(21):7814–7823. doi: 10.3390/ijms21217814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin M. S., Kim D., Yim K., et al. IL-7 receptor alpha defines heterogeneity and signature of human effector memory CD8+ T cells in high dimensional analysis. Cellular Immunology . 2020;355:104155–104159. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2020.104155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Z. H., Li Y., Liu W., Li X. Engineered IL-7 receptor enhances the therapeutic effect of AXL-CAR-T cells on triple-negative breast cancer. BioMed Research International . 2020;2020:13. doi: 10.1155/2020/4795171.4795171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lundtoft C., Afum-Adjei Awuah A., Rimpler J., et al. Aberrant plasma IL-7 and soluble IL-7 receptor levels indicate impaired T-cell response to IL-7 in human tuberculosis. European Journal of Immunology . 2017;13(6):1–22. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Kuraishy H. M., Al-Gareeb A. I., Al-Nami M. S. Vinpocetine improves oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory mediators in acute kidney injury. International Journal of Preventive Medicine . 2019;10(1):142–142. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_5_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiong X. Y., Bai L., Bai S. J., Wang Y. K., Ji T. Uric acid induced epithelial−mesenchymal transition of renal tubular cells through PI3K/p-Akt signaling pathway. Journal of Cellular Physiology . 2019;234(9):15563–15569. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fiseha T., Mengesha T., Girma R., Kebede E., Gebreweld A. Estimation of renal function in adult outpatients with normal serum creatinine. BioMed Central . 2019;12(1):462–467. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4487-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang R., Hu H. T., Hu S., He H., Shui H. β2-microglobulin is an independent indicator of acute kidney injury and outcomes in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Medicine . 2020;99(8, article e19212) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang X., Zhao K., Deng W., et al. Apocynin attenuates acute kidney injury and inflammation in rats with acute hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis. Digestive Diseases and Sciences . 2020;65(6):1735–1747. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05892-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bian M., Wang J., Wang Y., et al. Chicory ameliorates hyperuricemia via modulating gut microbiota and alleviating LPS/TLR4 axis in quail. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy . 2020;131:p. 110719. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hatakeyama Y., Horino T., Nagata K., et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of estimated baseline serum creatinine for acute kidney injury diagnosis. Clinical and Experimental Nephrology . 2018;22(2):405–412. doi: 10.1007/s10157-017-1481-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meng X. W., He C. X., Chen X., Yang X. S., Liu C. The extract of _Gnaphalium affine_ D. Don protects against H2O2-induced apoptosis by targeting PI3K/AKT/GSK-3 β signaling pathway in cardiomyocytes. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2021;268:p. 113579. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakamura Y., Kobayashi H., Tanaka S., Yoshinari H., Noboru F., Masanori A. Association between plasma aldosterone, and markers of tubular and glomerular damage in primary aldosteronism. Clinical Endocrinology . 2021;94(6):920–926. doi: 10.1111/cen.14434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Milanesi S., Verzola D., Cappadona F., et al. Uric acid and angiotensin II additively promote inflammation and oxidative stress in human proximal tubule cells by activation of toll-like receptor 4. Journal of Cellular Physiology . 2019;234(7):10868–10876. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The [data type] data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.