Abstract

Internal carotid artery (ICA) injury is a catastrophic complication of endoscopic endonasal surgery (EES). However, its standard management, emergent endovascular treatment, may not always be available, and the transnasal approach may be insufficient to achieve hemostasis.

A 44-year-old woman with pituitary adenoma underwent EES complicated with the ICA cavernous segment injury (CSI). In urgent intraoperative angiogram, a good collateral flow from the contralateral carotid circulation was observed. Due to the unavailability of intraoperative embolization, emergent surgical trapping was performed by combined transcranial and cervical approach. The patient recovered but later developed a giant cavernous pseudoaneurysm. During the pseudoaneurysm embolization, ICA was directly accessed via a 1.7-F puncture hole using a bare microcatheter technique. Then, both the aneurysm and parent artery were obliterated with coils. At the 4-year follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic without a residual tumor. To our knowledge, this is the first case of ICA–CSI during EES successfully treated with ICA trapping as a lifesaving urgent surgery that achieved a complete recovery after a pseudoaneurysm embolization. Although several studies reported that EES-related ICA–CSIs with percutaneous carotid artery access, neither our surgical salvage technique nor our carotid access and tract embolization techniques were previously described.

Keywords: endonasal endoscopic surgery, endovascular treatment, ICA-cavernous segment, pituitary adenoma, trapping, urgent transcranial surgery

Introduction

Recently, endoscopic endonasal surgery (EES) has been increasingly performed for skull base and sellar pathologies in patients of all ages, albeit its complications. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Despite the numerous reports on EES, there is a paucity of reports on its complications, especially those involving the internal carotid artery (ICA) injury, commonly at its cavernous part. 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 In this report, we present the first case treated with surgical trapping, an emergent surgical treatment, for EES-related carotid injury, and review 15 studies describing 33 cases of EES-related ICA–cavernous segment injury with special attention to treatment options. Our patient finally recovered well after the initial lifesaving surgical treatment followed by the unique endovascular approach for the residual carotid pseudoaneurysm in the subacute phase. Although direct endovascular treatment remains the best option for this catastrophic injury, alternative methods should also be known.

Case Report

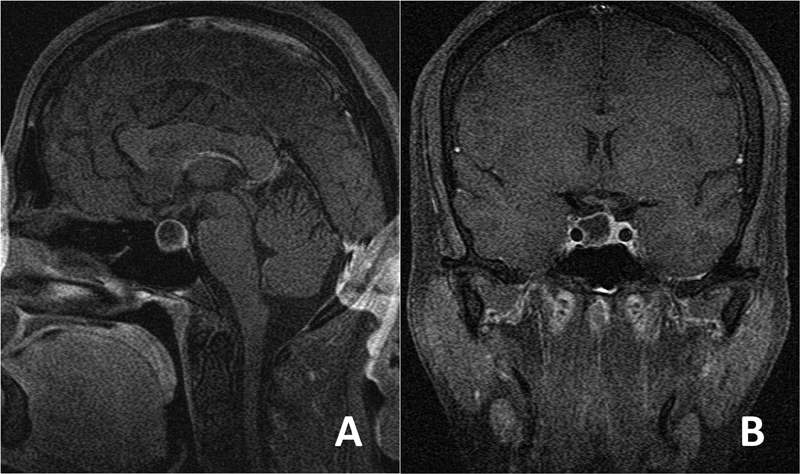

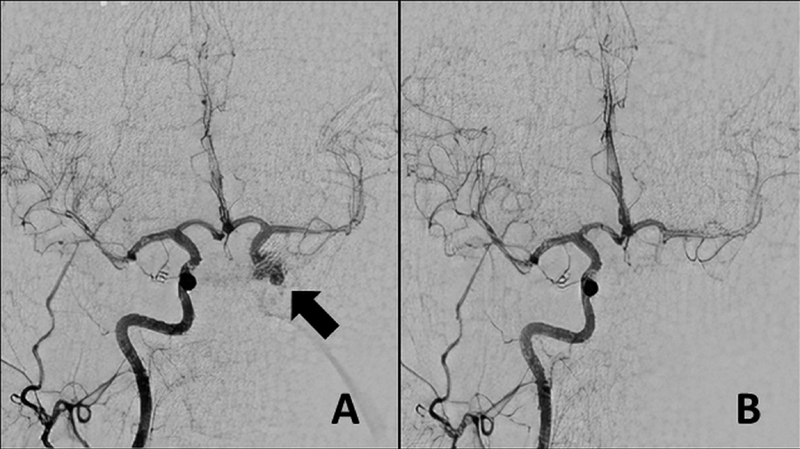

A 44-year-old female patient presented to our institution with hand and foot enlargement. On admission, no motor or sensory deficits were observed; however, bilateral temporal visual field cuts were detected. Laboratory workup revealed elevated somatomedin-C (IGF-1), 413 (94–269) ng/mL; somatotropin (GH), 3.86 (0–3.5) ng/mL; adrenocorticotropic hormone, 84.06 (7.2–63.3) pg/mL; and cortisol levels, 29.06 (6.7–42.6) µ. On magnetic resonance imaging, a macroadenoma was diagnosed ( Fig. 1A, B ), and the patient agreed to undergo an endonasal surgical treatment. Intraoperatively, the patient was placed in the standard supine position, with her head in a horseshoe cap and minimal extension. After reaching the sellar region, the bone was breached to reach the dura. As soon as the dura was reached using a number 15 blade, severe bleeding occurred. First, cotton, Surgicel (Ethicon) and bipolar cauterization and eventually muscle and fat tamponade were used but were unsuccessful to control the bleeding. Afterward, an emergent neck dissection was performed to place a temporary clip in the carotid artery. Then, as the bleeding was temporarily controlled, an intraoperative angiogram was performed, which revealed a lacerated cavernous ICA segment ( Fig. 2A ). A good collateral flow from the contralateral carotid circulation was also observed ( Fig. 2B ). Due to the unavailability of emergent neurointerventional support at that time, a decision was made to proceed with craniotomy emergently to prevent impending exsanguination and urgent transcranial surgery was performed. The patient was placed in supine position and the head was rotated at 30 degrees counterclockwise. A minipterional craniotomy was performed, and the anterior clinoid process was removed using a high-speed drill and rongeur extradurally. The dura was opened after removing the anterior clinoid process. On close inspection, no trace of subarachnoid hemorrhage and a normal appearing brain were observed. A proximal sylvian dissection was performed. All the supraclinoid portions of the ICA including the anterior choroidal, posterior communicating, and ophthalmic arteries were exposed. The ICA was trapped between its cervical and transitional segments (just proximal to the origin of the ophthalmic artery) by placing permanent aneurysm clips. Immediately after trapping, hemostasis was also verified endoscopically. Intraoperative Doppler sonography was used to determine the flow distal to the dural ring. After ensuring the distal flow, the tumor was completely removed via a transsylvian route. The patient again underwent an immediate postoperative angiography that confirmed the absence of bleeding and maintenance of good collateral supply to the ipsilateral carotid circulation above the cavernous segment. After a close observation in the neurointensive care unit postoperatively, the patient was transferred to the neurosurgical ward on postoperative day 3 with a Glasgow Coma Score of 15 and an intact neurological examination, except for left ptosis. On follow-up, the patient's serum hormone levels were normalized, and the ptosis had significantly improved at 6 months. The patient was readmitted to another institution for follow-up angiography at 11 months postoperatively. A cerebral angiogram demonstrated reconstitution of ICA flow inferiorly via the left vertebral and external carotid arteries ( Supplementary file 1 ). Below the carotid bifurcation, the common carotid artery was completely occluded. Superiorly, a persistent flow in the internal carotid circulation was observed via a significantly stenosed parent artery at the level of the previously placed clip. In the interim, an ∼40-mm cavernous pseudoaneurysm had developed. After consultation with the previous operator, endovascular approach was planned for the pseudoaneurysm. However, there was no antegrade access to the pseudoaneurysm from the aortic arch due to the previous carotid sacrifice ( Supplementary file 1 ). Under general anesthesia, the left vertebral artery was first catheterized through a transfemoral route. Vertebral angiograms demonstrated reconstruction of the left internal carotid circulation via the external carotid and distally to the posterior communicating arteries and antegrade filling of giant pseudoaneurysm and the ICA ( Supplementary file 1 ). Since the ICA had been surgically occluded, direct carotid puncture at the cervical segment of the ICA was performed using a 21-G micropuncture needle (Merit Medical Systems, United States) under fluoroscopic guidance ( Supplementary file 1 ). A Transcend 14 microwire (Stryker Neurovascular, United States) was placed through the needle, and then the needle was directly exchanged with an SL-10 microcatheter (Stryker Neurovascular, United States) over the Transcend microwire without using a vascular sheath ( Supplementary file 1 ). The supraclinoid portion of the left ICA was directly catheterized with the same microcatheter over a Synchro 14 microwire (Stryker Neurovascular, United States). The giant aneurysm and its neighboring parent artery were occluded with detachable bare platinum coils followed by an N-butyl cyanoacrylate injection. At the end of the procedure, both aneurysm and neighboring left ICA segment occlusion were demonstrated and left intracranial carotid circulation reconstruction was verified on the left vertebral and right carotid angiograms ( Supplementary file 1 ). While withdrawing the microcatheter, a glue bubble was first formed at the tip of the microcatheter by very slowly injecting an embolizing agent, and then the glue bubble was gently retracted with the microcatheter down the puncture site to plug the puncture hole from the endoluminal site. Subsequently, the glue was injected into the puncture tract while further withdrawing the microcatheter ( Supplementary file 1 ). Manual compression was not applied, and no neck hematoma was observed at the puncture site. The patient awakened from anesthesia uneventfully. Further follow-up showed persistent pseudoaneurysm and parent artery occlusion. The patient was asymptomatic including her previously affected third nerve function, and she had a normal hormonal profile at the 4-year follow-up.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the patient in sagittal ( A ) and coronal ( B ) sections demonstrating the pituitary adenoma.

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative emergent angiography showed left internal carotid artery (ICA)–cavernous segment injury (arrow) ( A ) and good collateral flow from the right ICA circulation ( B ).

Discussion

EES has become a routine approach for lesions extending from the frontal sinus to the second cervical vertebra in the sagittal plane and from the roof of the orbit and floor of the middle cranial fossa to the jugular foramen in the coronal plane in skull base surgery. 26 27 The main advantages of EES are absence of skin incisions (cosmetically more acceptable), minimally invasive nature, diminished postoperative pain, and short duration of postoperative hospital stay, which promoted its popularity. 26 In spite of these advantages, certain complications may occur, including but not limited to hemorrhagic vascular complications, rhinorrhea, and infection. 2 28 29 Among these, ICA injury is a life-threatening complication of EES. 5 17 29 30 31

The incidence of ICA injury during neurosurgical transsphenoidal interventions is 0.2 to 1.4% for pituitary surgery. 17 31 ICA injury during EES is rare and less common as compared with microsurgical series. 17 32 33 34 35 On the other hand, some studies have revealed contrasting opinions. 36 Obviously, the rule of thumb is to prevent these injuries by proper training and operator experience, using the “2 surgeons, 4 hands” method, and having a good grasp of patient-specific anatomy utilizing the best preoperative imaging techniques. 30 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 Anatomical considerations in EES must be kept in the mind to avoid this serious complication. 44 45 46 However, ICA injury may still occur in the best of hands, 47 and apart from exsanguination, this injury may lead to a diverse range of vascular findings such as pseudoaneurysms, arterial spasm, arterial thrombosis/emboli, and caroticocavernous fistula formation. 3 4 Although endovascular treatment is currently the best choice for the management of ICA injury during EES, surgical options must be considered in cases of unavailable or delayed emergent endovascular treatment. 8 9 25 48 49 50 51 Therefore, this report aimed to describe the alternative surgical approach in such case scenario by demonstrating our case and a literature review. Surprisingly, we discovered that this process with subsequent ICA trapping in the hyperacute phase has not yet been reported in the literature, although reverting to craniotomy in such a catastrophic emergency is basically an intuitive procedure.

Several literature reports showed data on ICA–cavernous segment injury during EES operations, as summarized in Table 1 . 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 In a larger series, Romero et al described four arterial injuries out of their 800 EES cases. 23 However, only one of these injuries occurred in the cavernous ICA. In this case, an emergent angiogram showed sufficient collaterals via the circle of Willis; therefore, the operators were able to proceed with the endovascular occlusion of ICA, and 4 months later, they removed the tumor via orbitofrontal craniotomy. Additionally, in same study, the authors reviewed the literature and described that 25 out of 7,336 patients undergoing EES had arterial injury intraoperatively (0.34%). They found 19 ICA injuries in the same (0.26%) meta-analysis. In the largest series of EES describing ICA injury, Kalinin et al described four cases of ICA–cavernosal segment injury in their 3,000 patients from Burdenko (0.13%). 19 Among them, one had ICA occlusion and three had pseudoaneurysm formation; three of them underwent endovascular treatment. One patient required bilateral decompressive craniotomy postoperatively and subsequently died. In a systematic review on ICA injury in EES, Chin et al evaluated 25 papers revealing 50 patients with injury 52 : 34 at the ICA–cavernous segment and 3 at the ophthalmic artery, occurring more commonly on the left eye (1.3/1). In 35 patients who achieved initial hemostasis through packing, four underwent an endoscopic clip sacrifice, three had bipolar coagulation to seal the defect, and one had bipolar coagulation to sacrifice the ICA. Intraoperative or immediate postoperative angiography was reported in 27 cases in this meta-analysis. Our literature review, as summarized in Table 1 , yielded 33 patients (12 males and 15 females; no gender information was available for 6 patients) with a mean age of 47.36 years (range: 12–82 years). The most common pathology was pituitary tumor (18 patients: 4 patients with acromegaly, 4 with nonfunctional tumors, 2 with Cushing syndrome, 2 with prolactinomas, and the lesion type was not provided for 6 patients). The other pathologies were chordoma-chondrosarcomas in five patients, meningiomas in three patients, carcinoma in two patients, and one patient had craniopharyngioma, fibrous dysplasia, Rathke cleft cyst, giant cell tumor, and endoscopic sinus surgery each. In total, cavernous segment injury occurred mostly during tumor resection in nine patients and drilling/remove bone in eight patients; it also occurred during tumor dissection in five patients, dura incision in three patients, and finally during hemostasis stage in one patient. It was reported to occur spontaneously in one patient, whereas no such data was obtained for six patients. The injury was left-sided in 11 patients and right-sided in 9 patients (data unavailable for 13 patients). Packing was the most common initial method to treat the injury (16 patients). An immediate angiogram was performed in all patients except one (no data for one series). Endovascular treatment was the most commonly used treatment method. Most patients had no sequelae (21 cases) and were alive; however, sufficient information on outcomes was lacking in seven patients. One patient had a sequela and another died due to unrelated reasons later. Three deaths were directly related to the procedure.

Table 1. Previous literature data on patients with ICA-cavernous segment injury during EES.

| P | S/ Re | A/G | Pathology | Injury | Side | Initial | IA | Finding | ICA status/Repair | Patient status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 (11,12) |

22/F | PT-Acro | TD | R | Pac | + | PA | EC | NS |

| 2 | 2 (13) |

42/M | Car | TD | L | Pac | + | PA | EBO | Li/NA |

| 3 | 3 (14) |

31/M | PT-Acro | un | L | Pac | + | un | EC | NS |

| 4 | 4 (15) |

45/M | PT-NP | DI | R | Pac + MP | + | un | ESt + EC | NS |

| 5 | 4 (15) |

12/M | PT-Cushing | DRB | un | Pac | + | un | ESt + EC | NS |

| 6 | 5 (16) |

41/F | PT-Cushing | DRB | un | un | + | Aneurysm | ESt | NS |

| 7 | 6 (17) |

un | PT-NP | TD | L | SKC | un | Stenosis | ESa | Ex |

| 8 | 6 (17) |

un | PT-PRL | TR | L | BS | un | PA | EVt | NS |

| 9 | 6 (17) |

un | C | TD | L | BS | un | Stenosis | EC | NS |

| 10 | 6 (17) |

un | C | TR | R | BS | un | un | ICA intact | UEx |

| 11 | 6 (17) |

un | M | DRB | R | Pac | un | Mild stenosis | ICA intact | NS |

| 12 | 7 (18) |

31/M | GCT | DRB | L | Pac | + | MCA thrombus | EC | NS |

| 13 | 8 (19) |

54/F | PT-NP | TR | L | Pac | + | Stenosis | No treatment/surgery | Ex |

| 14 | 8 (19) |

61/F | PT-NP | DI | R | Un | + | ICA wall defect | Good collateral EBO |

Ex |

| 15 | 8 (19) |

40/F | PT-Acro | DI | L | Un | + | un | Good collateral EBO |

NS |

| 16 | 8 (19) |

46/M | PT-PRL | HS | R | Un | + | PA | ESt | NS a |

| 17 | 9 (20) |

29/F | PT | un | un | Pac | + | PA PCF |

ICA-MCA bypass | Li/NA |

| 18 | 9 (20) |

45/M | PT | un | un | Pac | + | PCF | ICA-MCA bypass | Li/NA |

| 19 | 9 (20) |

38/M | RCC | un | un | Pac | + | PA | ICA-MCA bypass | Li/NA |

| 20 | 9 (20) |

65/M | C | un | R | Pac | + | Stenosis | EVt + ICA-MCA bypass | Li/NA |

| 21 | 10 (21) |

37/M | PT | TD | un | AC + MP | + | N | N | NS |

| 22 | 10 (21) |

50/F | C | TR | un | AC + MP | + | N | N | NS |

| 23 | 10 (21) |

54/F | PT | TR | un | AC + MP | + | Limited ICA flow | ESt | Li/NA |

| 24 | 10 (21) |

76/F | Cra | DRB | un | AC + MP | + | N | N | NS |

| 25 | 10 (21) |

40/F | PT | Spo | un | AC + MP | + | No ICA flow | Good collateral | NS |

| 26 | 10 (21) |

82/F | M | DRB | un | AC + MP | + | N | N | NS |

| 27 | 10 (21) |

58/F | FD | DRB | un | AC + MP | + | PA | ESt | NS |

| 28 | 10 (21) |

69/M | Car | TR | un | AC + MP | + | CD | Observed | Li/NA |

| 29 | 11 (22) |

un | PT | TR | L | Pac | + | ICA Wall defect |

EBO TCS b |

Sq c |

| 30 | 12 (23) |

67/F | M | DRB | R | Pac | + | ICA Wall defect |

Good Collateral EC |

NS d |

| 31 | 13 (24) |

44/M | ESS | un | R | un | + | PA | EC | NS |

| 32 | 14 (25) |

57/F | C | TR | L | Pac | − | PA | un | NS |

| 33 | CR | 44/F | PT-Acro | TR | L | Pac | + | ICA Wall defect | ICA trapping operation |

NS |

Abbreviations: A, age; Acro, acromegaly; AC, aneurysm clip; BS, bipolar coagulation/sealing-sacrifice; C, chordoma/chondrosarcoma; Car, carcinoma; CD, carotid dissection; CR, current report; Cra, craniopharyngioma; DI, dura incision; DRB, drilling/remove bone; EBO, endovascular balloon occlusion; EC, endovascular coil; ESa, endovascular sacrifice; ESt, endovascular stenting; EVt, endovascular thrombectomy; ESS, endoscopic sinus surgery; Ex, exitus; FD, fibrous dysplasia; G, gender; GCT, giant cell tumor; HS, hemostasis stage; IA, immediate angiogram; ICA, internal carotid artery; L, left, Li, alive; M, meningioma; MC, microcatheter; MCA, middle cerebral artery; MP, muscular patch; N, normal; NA, not applicable; NBCA, acrylic glue mixed with lipiodol; NP, nonfunctional pituitary tumor; NS, no sequelae; P, patient; Pac, packing; PA, pseudoaneurysm; PCF, poor collateral flow; PRL, prolactinoma; PT, pituitary tumor; Re, references; R, right; RCC, Rathke cleft cyst; S, study; Spo, spontaneous; SKC, Sundt–Kees aneurysm clip; Sq, sequelae; TCS, transcranial surgery; TD, tumor dissection/exposure; TR, tumor resection; UEx, unrelated/delayed ex; un, unknown.

1. 11,12 (Cappabianca et al, 2001)

2. 13 (Liu and Di, 2009)

3. 14 (Zada et al, 2010)

4. 15 (Gondim et al, 2011)

5. 16 (Berker et al, 2012)

6. 17 (Gardner et al, 2013)

7. 18 (Iacoangeli et al, 2013)

8. 19 (Kalinin et al, 2013)

9. 20 (Rangel-Castilla et al, 2014)

10. 21 (Padhye et al, 2015)

11. 22 (Magro et al, 2016)

12. 23 (Romero et al, 2017)

13. 24 (Dedmon et al, 2014)

14. 25 (Duek et al, 2017)

Without augmentation of focal neurological deficit.

Because of the packing and hematoma, the patient had visual worsening that required an intracranial approach.

Visual field and acuity remained severely worsened.

Four months later, the patient received an orbitofrontal craniotomy to remove the tumor.

Although several model studies and surgical simulations have been reported on the management of this complication, vascular injury can be managed with a few methods in the acute setting. 53 54 55 56 57 58 In cases of small injury, the opening can be sealed off with the help of a bipolar electrode with or without using the muscle tissue. 5 41 59 60 61 However, this may result in pseudoaneurysm formation with unstable seal. 62 63 64 Suturing the site of injury is an option; however, it can be hard to perform in EES and generally results in a high-degree stenosis. 4 Again, clipping the injury site is also an option; however, this can lead to pseudoaneurysm formation, if not stenosis or ischemia. 59 60 If none of these is possible, the artery should be temporarily wrapped, and endovascular treatment should be considered. 8 30 49 65 66 67 68 Padhye et al described the effects of endoscopic direct clamp closure and muscle patch application in their multicenter study. 21 Among nine patients with arterial injury during EES (one basilar artery and eight ICA), no deaths occurred, one had pseudoaneurysm with successful endovascular treatment, two had impaired carotid flow, and one with carotid dissection was conservatively managed. Finally, if endovascular options are limited or unavailable, transcranial approaches such as an extracranial-to-intracranial bypass or transcavernous approach can be utilized in arterial or ICA injury due to a transsphenoidal approach. 20 69 70 In our case, ICA trapping was performed based on the intraoperative angiogram, because proximal arterial control should be first achieved via a cervical incision. Since this remained as our only means to salvage the injury, we suggest that tissues surrounding the carotid sheath should be carefully maintained intraoperatively in widely spread lesions like chordomas.

The largest number of ICA injuries from a single center was described by Gardner et al. 17 who found seven patients with a 0.3% incidence. They performed bipolar coagulation/sealing, with Sundt-Kees aneurysm clip or clip sacrifice, in these patients with further endovascular treatment during follow-up in some patients. A particular endovascular approach was also utilized in our patient during follow-up. Due to the reconstitution of the internal carotid flow via external carotid artery branches above the clipped segment of the carotid artery, vascular access options were limited. The transwillis approach was possible but would endanger both carotid circulations should a problem occur during embolization. Hence, the operator opted to puncture the cervical ICA directly and used the microcatheter alone, (without a sheath, needle, or catheter) to navigate until the dural ring level to perform parent artery occlusion with coils. Since arterial puncture occurred above the neck of the mandible, hemostasis using compression would be impossible. Although the use of arterial closure devices in the cervical approach has been described, 71 the lack of a safe distal landing zone for the deployment sheath in our case precluded the use of these devices. Consequently, the operator preferred to perform puncture-track embolization using the cyanoacrylate glue. A similar endovascular approach alone for internal carotid access without surgically exposing the carotid artery was previously reported in the literature in four papers to treat a total of five patients with residual carotid cavernous fistulas and one with a history of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and radiotherapy to acute carotid blow-out. 72 73 74 75 Review of these six patients is presented in Table 2 . Among them, Tsai et al could puncture the carotid artery low enough to enable sheath placement and subsequent closure with an arterial closure device, and Halbach et al also used a large sheath and finally embolized the carotid artery with coils. Khan et al used an 18-G needle as an access sheath, whereas Chang et al performed the embolization procedure only using a 19-G needle. A bare microcatheter technique using merely a microcatheter without an outer sheath or needle has not been reported to directly access the ICA, to our knowledge. This bare microcatheter technique allowed us to make a 1.7-F puncture hole only in the carotid artery, minimizing the risk of a puncture site hematoma. Regardless of this tiny hole, we further secured the access tract-by “tract embolization” with liquid embolic agents, which, again to our knowledge, has not been previously performed for carotid access.

Table 2. Previous literature data on patients treated with direct ICA artery percutaneous access, without surgically exposing the artery.

| P | S/Re | A/G | Underlying pathology | Primary puncture site | Primary access method | Primary access equipment | Endovascular treatment | Angiographic result | Clinical result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–3 | 1 (72) | un | Caroticocavernous fistulas | ICA | Fluoroscopic guidance | 18-G needle, then 5.5 to 7.3-F sheaths | Coiling + detachable balloon |

Obliteration of the fistula | Disappearance of fistula related symptoms |

| 4 | 2 (73) | 58, M | Acute blow-out secondary to radiation and pseudoaneurysm | ICA | Fluoroscopic guidance | 19-Gauge spinal needle | Coiling + NBCA injection |

Disappearance of extravasation and pseudoaneurysm | Death due to accompanying medical conditions |

| 5 | 3 (74) | 47/M | Caroticocavernous fistula | ICA | Fluoroscopic guidance | 18-G needle, then 5-F sheath | Coiling + NBCA injection |

Obliteration of the fistula | Disappearance of fistula related symptoms |

| 6 | 4 (75) | 20, M | Iatrogenic caroticocavernous fistula, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome | ICA | Ultrasound/Fluoroscopic guidance | 18-Gauge angiocath | Coiling | Minimal filling of the fistula | Regression of neurological symptoms |

| 7 | CR | 44/F | Cavernous aneurysm | ICA | Fluoroscopic guidance | 21-G needle, then MC directly over the microwire | Coiling + NBCA injection, tract embolization |

Obliteration of aneurysm and parent artery | Disappearance of aneurysm and third nerve palsy |

Abbreviations: A, age; CR, current report; G, gender; ICA, internal carotid artery; MC, microcatheter; NBCA, acrylic glue mixed with lipiodol; P, patient; Re, references; S, study; un, unknown.

1. 72 (Halbach et al, 1989)-3 patients

2. 73 (Chang et al, 2005)

3. 74 (Tsai et al, 2010)

4. 75 (Khan et al, 2012)

Conclusion

ICA injury is one of the serious complications that can occur during EES. In our rare case, this EES complication was successfully managed in a unique manner, by reverting to transcranial/transcervical carotid trapping followed by a parent artery sacrifice with direct internal carotid puncture, using a bare microcatheter technique and tract embolization. Both techniques may be lifesaving in case of a devastating carotid injury during EES.

Abbreviations

- A

Age

- Acro

Acromegaly

- AC

Aneurysm clip

- BS

Bipolar coagulation/sealing-sacrifice

- C

Chordoma/chondrosarcoma

- Car

Carcinoma

- CD

Carotid Dissection

- CR

Current report

- Cra

Craniopharyngioma

- DI

Dura incision

- DRB

Drilling/remove bone

- EBO

Endovascular balloon occlusion

- EC

Endovascular coil

- ESa

Endovascular sacrifice

- ESt

Endovascular stenting

- EVt

Endovascular thrombectomy

- ESS

Endoscopic sinus surgery

- Ex

Exitus

- FD

Fibrous dysplasia

- G

Gender

- GCT

Giant cell tumor

- HS

Haemostasis stage

- IA

Immediate angiogram

- ICA

Internal carotid artery

- L

Left

- Li

Alive

- M

Meningioma

- MC

Microcatheter

- MCA

Middle cerebral artery

- MP

Muscular patch

- N

Normal

- NA

Not applicable

- NBCA

Acrylic glue mixed with lipiodol

- NP

Non-functional pituitary tumor

- NS

No sequelae

- P

Patient

- Pac

Packing

- PA

Pseudoaneurysm

- PCF

Poor collateral flow

- PRL

Prolactinoma

- PT

Pituitary tumor

- Re

References

- R

Right

- RCC

Rathke cleft cyst

- S

Study

- Spo

Spontaneous

- SKC

Sundt–Kees aneurysm clip

- Sq

Sequelae

- TCS

Transcranial surgery

- TD

Tumor dissection/exposure

- TR

Tumor resection

- UEx

Unrelated/delayed ex

- un

Unknown

Funding Statement

Funding None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Schwartz T H, Fraser J F, Brown S, Tabaee A, Kacker A, Anand V K.Endoscopic cranial base surgery: classification of operative approaches Neurosurgery 20086205991–1002., discussion 1002–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciric I, Ragin A, Baumgartner C, Pierce D.Complications of transsphenoidal surgery: results of a national survey, review of the literature, and personal experience Neurosurgery 19974002225–236., discussion 236–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berker M, Aghayev K, Saatci I, Palaoğlu S, Onerci M. Overview of vascular complications of pituitary surgery with special emphasis on unexpected abnormality. Pituitary. 2010;13(02):160–167. doi: 10.1007/s11102-009-0198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solares C A, Ong Y K, Carrau R L. Prevention and management of vascular injuries in endoscopic surgery of the sinonasal tract and skull base. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2010;43(04):817–825. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weidenbecher M, Huk W J, Iro H. Internal carotid artery injury during functional endoscopic sinus surgery and its management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262(08):640–645. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0888-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babgi M, Alsaleh S, Babgi Y, Baeesa S, Ajlan A. Intracranial intradural vascular injury during endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery: a case report and literature review. J Neurol Surg Rep. 2020;81(03):e52–e58. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1717056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahilogullari G, Meco C, Beton S. Endoscopic transnasal skull base surgery in pediatric patients. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2020;81(05):515–525. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1692641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kocer N, Kizilkilic O, Albayram S, Adaletli I, Kantarci F, Islak C. Treatment of iatrogenic internal carotid artery laceration and carotid cavernous fistula with endovascular stent-graft placement. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(03):442–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safaee M, Young J S, El-Sayed I H, Theodosopoulos P V. Management of noncatastrophic internal carotid artery injury in endoscopic skull base surgery. Cureus. 2019;11(08):e5537. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pham M, Kale A, Marquez Y. Management of carotid artery injury during endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2014;75:309–313. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cappabianca P, Briganti F, Cavallo L M, de Divitiis E. Pseudoaneurysm of the intracavernous carotid artery following endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery, treated by endovascular approach. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2001;143(01):95–96. doi: 10.1007/s007010170144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cappabianca P, Cavallo L M, Colao A, de Divitiis E. Surgical complications associated with the endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach for pituitary adenomas. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(02):293–298. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.2.0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu H S, Di X. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for biopsy of cavernous sinus lesions. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2009;52(02):69–73. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1192015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zada G, Cavallo L M, Esposito F. Transsphenoidal surgery in patients with acromegaly: operative strategies for overcoming technically challenging anatomical variations. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;29(04):E8. doi: 10.3171/2010.8.FOCUS10156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gondim J A, Almeida J PC, Albuquerque L A. Endoscopic endonasal approach for pituitary adenoma: surgical complications in 301 patients. Pituitary. 2011;14(02):174–183. doi: 10.1007/s11102-010-0280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berker M, Hazer D B, Yücel T. Complications of endoscopic surgery of the pituitary adenomas: analysis of 570 patients and review of the literature. Pituitary. 2012;15(03):288–300. doi: 10.1007/s11102-011-0368-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner P A, Tormenti M J, Pant H, Fernandez-Miranda J C, Snyderman C H, Horowitz M B.Carotid artery injury during endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery: incidence and outcomesNeurosurgery 2013;73(2, Suppl Operative):ons261ȃons269, discussion ons269–ons270 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Iacoangeli M, Di Rienzo A, Re M. Endoscopic endonasal approach for the treatment of a large clival giant cell tumor complicated by an intraoperative internal carotid artery rupture. Cancer Manag Res. 2013;5:21–24. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S38768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalinin P L, Sharipov O I, Shkarubo A N.[Damage to the cavernous segment of internal carotid artery in transsphenoidal endoscopic removal of pituitary adenomas (report of 4 cases)] Vopr Neirokhir 2013770628–37., discussion 38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rangel-Castilla L, McDougall C G, Spetzler R F, Nakaji P.Urgent cerebral revascularization bypass surgery for iatrogenic skull base internal carotid artery injury Neurosurgery 20141004640–647., discussion 647–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padhye V, Valentine R, Sacks R. Coping with catastrophe: the value of endoscopic vascular injury training. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5(03):247–252. doi: 10.1002/alr.21471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magro E, Graillon T, Lassave J. Complications related to the endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach for nonfunctioning pituitary macroadenomas in 300 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2016;89:442–453. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romero A DCB, Lal Gangadharan J, Bander E D, Gobin Y P, Anand V K, Schwartz T H. Managing arterial injury in endoscopic skull base surgery: case series and review of the literature. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2017;13(01):138–149. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dedmon M, Meier J, Chambers K. Delayed endovascular coil extrusation following internal carotid artery embolization. J Neurol Surg Rep. 2014;75(02):e255–e258. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1387193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duek I, Sviri G E, Amit M, Gil Z. Endoscopic endonasal repair of internal carotid artery injury during endoscopic endonasal surgery. J Neurol Surg Rep. 2017;78(04):e125–e128. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1608635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snyderman C H, Pant H, Carrau R L, Prevedello D, Gardner P, Kassam A B. What are the limits of endoscopic sinus surgery?: the expanded endonasal approach to the skull base. Keio J Med. 2009;58(03):152–160. doi: 10.2302/kjm.58.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dehdashti A R, Ganna A, Witterick I, Gentili F.Expanded endoscopic endonasal approach for anterior cranial base and suprasellar lesions: indications and limitations Neurosurgery 20096404677–687., discussion 687–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zanation A M, Carrau R L, Snyderman C H. Nasoseptal flap reconstruction of high flow intraoperative cerebral spinal fluid leaks during endoscopic skull base surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23(05):518–521. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cavallo L M, Briganti F, Cappabianca P. Hemorrhagic vascular complications of endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2004;47(03):145–150. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-818489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valentine R, Wormald P J. Carotid artery injury after endonasal surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011;44(05):1059–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laws E R., Jr Vascular complications of transsphenoidal surgery. Pituitary. 1999;2(02):163–170. doi: 10.1023/a:1009951917649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alahmadi H, Dehdashti A R, Gentili F.Endoscopic endonasal surgery in recurrent and residual pituitary adenomas after microscopic resection World Neurosurg 201277(3-4):540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pasquini E, Zoli M, Frank G.Endoscopic endonasal surgery: new perspectives in recurrent and residual pituitary adenomas World Neurosurg 201277(3-4):457–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halvorsen H, Ramm-Pettersen J, Josefsen R. Surgical complications after transsphenoidal microscopic and endoscopic surgery for pituitary adenoma: a consecutive series of 506 procedures. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2014;156(03):441–449. doi: 10.1007/s00701-013-1959-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank G, Pasquini E, Farneti G.The endoscopic versus the traditional approach in pituitary surgery Neuroendocrinology 200683(3-4):240–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ammirati M, Wei L, Ciric I. Short-term outcome of endoscopic versus microscopic pituitary adenoma surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(08):843–849. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-303194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fang X, Di G, Zhou G. The anatomy of the parapharyngeal segment of the internal carotid artery for endoscopic endonasal approach. Neurosurg Rev. 2019;••• doi: 10.1007/s10143-019-01176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dal Secchi M M, Dolci R LL, Teixeira R, Lazarini P R. An analysis of anatomic variations of the sphenoid sinüs and its relationship to the internal carotid artery. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;22(02):161–166. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Truong H Q, Najera E, Zanabria-Ortiz R. Surgical anatomy of the superior hypophyseal artery and its relevance for endoscopic endonasal surgery. J Neurosurg. 2018;131(01):154–162. doi: 10.3171/2018.2.JNS172959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skandalakis G P, Koutsarnakis C, Pantazis N. The carotico-clinoid bar: a systematic review and meta-analysis of its prevalence and potential implications in cerebrovascular and skull base surgery. World Neurosurg. 2019;124:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rowan N R, Turner M T, Valappil B. Injury of the carotid artery during endoscopic endonasal surgery: surveys of skull base surgeons. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2018;79(03):302–308. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.AlQahtani A, London N R, Jr, Castelnuovo P. Assessment of factors associated with internal carotid injury in expanded endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(04):364–372. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.4864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dziedzic T, Koczyk K, Gotlib T, Kunert P, Maj E, Marchel A. Sphenoid sinus septations and their interconnections with parasphenoidal internal carotid artery protuberance: radioanatomical study with literature review. Wideochir Inne Tech Malo Inwazyjne. 2020;15(01):227–233. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2019.85837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erdogan U, Turhal G, Kaya I. Cavernous sinus and parasellar region: An endoscopic endonasal anatomic cadaver dissection. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29(07):e667–e670. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng Y, Zhao J W, Liu M. Internal carotid artery in the operative plane of endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23(03):909–912. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824ddf07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y, Tian Y, Song J, Li Y, Li W. Internal carotid artery in endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23(06):1866–1869. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31826bf22a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perry A, Graffeo C S, Meyer J. Beyond the learning curve: comparison of microscopic and endoscopic incidences of internal carotid artery injury in a series of highly experienced operators. World Neurosurg. 2019;131:e128–e135. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valentine R, Wormald P J. Controlling the surgical field during a large endoscopic vascular injury. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(03):562–566. doi: 10.1002/lary.21361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koitschev A, Simon C, Löwenheim H, Naegele T, Ernemann U. Management and outcome after internal carotid artery laceration during surgery of the paranasal sinuses. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;126(07):730–738. doi: 10.1080/00016480500469578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fastenberg J H, Garzon-Muvdi T, Hsue V. Adenosine-induced transient hypotension for carotid artery injury during endoscopic skull-base surgery: case report and review of the literature. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019;9(09):1023–1029. doi: 10.1002/alr.22381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang H K, Ma N, Sun X C, Wang D H. Endoscopic repair of the injured internal carotid artery utilizing oxidized regenerated cellulose and a free fascia lata graft. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(04):1021–1024. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chin O Y, Ghosh R, Fang C H, Baredes S, Liu J K, Eloy J A. Internal carotid artery injury in endoscopic endonasal surgery: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(03):582–590. doi: 10.1002/lary.25748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valentine R, Wormald P J. A vascular catastrophe during endonasal surgery: an endoscopic sheep model. Skull Base. 2011;21(02):109–114. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maza G, VanKoevering K K, Yanez-Siller J C. Surgical simulation of a catastrophic internal carotid artery injury: a laser-sintered model. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019;9(01):53–59. doi: 10.1002/alr.22178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muto J, Carrau R L, Oyama K, Otto B A, Prevedello D M. Training model for control of an internal carotid artery injury during transsphenoidal surgery. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(01):38–43. doi: 10.1002/lary.26181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pacca P, Jhawar S S, Seclen D V. ‘Live Cadaver’ model for internal carotid artery injury simulation in endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2017;13(06):732–738. doi: 10.1093/ons/opx035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shen J, Hur K, Zhang Z. Objective validation of perfusion-based human cadaveric simulation training model for management of internal carotid artery injury in endoscopic endonasal sinus and skull base surgery. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2018;15(02):231–238. doi: 10.1093/ons/opx262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dusick J R, Esposito F, Malkasian D, Kelly D F.Avoidance of carotid artery injuries in transsphenoidal surgery with the Doppler probe and micro-hook bladesNeurosurgery 2007;60(4, Suppl 2):322–328, discussion 328–329 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Raymond J, Hardy J, Czepko R, Roy D. Arterial injuries in transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary adenoma; the role of angiography and endovascular treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18(04):655–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ahuja A, Guterman L R, Hopkins L N.Carotid cavernous fistula and false aneurysm of the cavernous carotid artery: complications of transsphenoidal surgery Neurosurgery 19923104774–778., discussion 778–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang W H, Lieber S, Lan M Y. Nasopharyngeal muscle patch for the management of internal carotid artery injury in endoscopic endonasal surgery. J Neurosurg. 2019;18:1–6. doi: 10.3171/2019.7.JNS191370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Valentine R, Boase S, Jervis-Bardy J, Dones Cabral J D, Robinson S, Wormald P J. The efficacy of hemostatic techniques in the sheep model of carotid artery injury. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1(02):118–122. doi: 10.1002/alr.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Padhye V, Valentine R, Paramasivan S. Early and late complications of endoscopic hemostatic techniques following different carotid artery injury characteristics. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4(08):651–657. doi: 10.1002/alr.21326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karadag A, Kinali B, Ugur O, Oran I, Middlebrooks E H, Senoglu M. A case of pseudoaneurysm of the internal carotid artery following endoscopic endonasal pituitary surgery: endovascular treatment with flow-diverting stent implantation. Acta Med (Hradec Kralove) 2017;60(02):89–92. doi: 10.14712/18059694.2017.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Biswas D, Daudia A, Jones N S, McConachie N S. Profuse epistaxis following sphenoid surgery: a ruptured carotid artery pseudoaneurysm and its management. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123(06):692–694. doi: 10.1017/S0022215108002752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cobb M I, Nimjee S, Gonzalez L F, Jang D W, Zomorodi A.Direct repair of iatrogenic internal carotid artery injury during endoscopic endonasal approach surgery with temporary endovascular balloon-assisted occlusion: technical case report Neurosurgery 20151103E483–E486., discussion E486–E487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang Y, Tian Z, Li C. A modified endovascular treatment protocol for iatrogenic internal carotid artery injuries following endoscopic endonasal surgery. J Neurosurg. 2019;132(02):343–350. doi: 10.3171/2018.8.JNS181048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sylvester P T, Moran C J, Derdeyn C P. Endovascular management of internal carotid artery injuries secondary to endonasal surgery: case series and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2016;125(05):1256–1276. doi: 10.3171/2015.6.JNS142483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dolenc V V, Lipovsek M, Slokan S. Traumatic aneurysm and carotid-cavernous fistula following transsphenoidal approach to a pituitary adenoma: treatment by transcranial operation. Br J Neurosurg. 1999;13(02):185–188. doi: 10.1080/02688699943961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oskouian R J, Kelly D F, Laws E RJ., Jr Vascular injury and transsphenoidal surgery. Front Horm Res. 2006;34:256–278. doi: 10.1159/000091586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orlov K, Arat A, Osiev A.Transvenous treatment of carotid aneurysms through transseptal access World Neurosurg 2019S1878–8750.(19)30086-5. Doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.12.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Halbach V V, Higashida R T, Hieshima G B, Hardin C W. Direct puncture of the proximally occluded internal carotid artery for treatment of carotid cavernous fistulas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1989;10(01):151–154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chang F C, Lirng J F, Luo C B, Teng M M, Guo W Y, Chang C Y. Carotid blowout treated by direct percutaneous puncture of internal carotid artery with temporary balloon occlusion. Interv Neuroradiol. 2005;11(04):349–354. doi: 10.1177/159101990501100407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tsai Y H, Weng H H, Chen Y L, Wu Y M, Wong H F. Treatment of recurrent carotid cavernous fistula by direct puncture of a previously trapped internal carotid artery. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21(05):738–740. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Khan A, Chaudhary N, Pandey A S, Gemmete J J. Direct puncture of the highest cervical segment of the internal carotid artery for treatment of an iatrogenic carotid cavernous fistula in a patient with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Neurointerv Surg. 2012;4(05):e29. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2011-010075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.