Abstract

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the AP endonucleases encoded by the APN1 and APN2 genes provide alternate pathways for the removal of abasic sites. Oxidative DNA-damaging agents, such as H2O2, produce DNA strand breaks which contain 3′-phosphate or 3′-phosphoglycolate termini. Such 3′ termini are inhibitory to synthesis by DNA polymerases. Here, we show that purified yeast Apn2 protein contains 3′-phosphodiesterase and 3′→5′ exonuclease activities, and mutation of the active-site residue Glu59 to Ala in Apn2 inactivates both these activities. Consistent with these biochemical observations, genetic studies indicate the involvement of APN2 in the repair of H2O2-induced DNA damage in a pathway alternate to APN1, and the Ala59 mutation inactivates this function of Apn2. From these results, we conclude that the ability of Apn2 to remove 3′-end groups from DNA is paramount for the repair of strand breaks arising from the reaction of DNA with reactive oxygen species.

Oxygen free radicals formed during normal cellular oxidative metabolism produce DNA damage such as abasic (AP) sites, DNA strand breaks, and modified miscoding bases. AP sites are also formed by spontaneous base hydrolysis. It has been estimated that as many as 104 purines are lost spontaneously in a mammalian cell per day (6). Cells possess class II AP endonucleases that remove the AP sites by cleaving the phosphodiester backbone on the 5′ side of the lesion, producing a 3′-OH group and a 5′-baseless deoxyribose 5′-phosphate residue. Removal of the 5′ AP residue followed by DNA repair synthesis and ligation complete the repair process (9, 13). A characteristic form of oxidative damage is a free radical-initiated DNA strand break bearing a 3′-phosphate or a 3′-phosphoglycolate (3′-PG) terminus (3, 4). These 3′-end groups are a block to synthesis by DNA polymerases and must be removed for subsequent repair to occur (2). Class II AP endonucleases also function in the removal of such 3′ termini.

Two families of class II AP endonuclease 3′-repair diesterase enzymes have been identified. One of these includes endonuclease IV of Escherichia coli and its homolog, the Apn1 protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Endonuclease IV represents ∼10 and 50% of the total AP endonuclease activity in uninduced and induced bacterial cells, respectively, while Apn1 is the major AP endonuclease in yeast, representing >90% of the activity in yeast cells. Both enzymes also possess a 3′-phosphatase and a 3′-phosphodiesterase activity that can remove the 3′-terminal groups formed in DNA by free radical attack or by the action of DNA glycosylase-associated β-lyase activity (9, 13).

The second family of class II AP endonucleases includes exonuclease III (ExoIII) of E. coli, the Apn2 protein of S. cerevisiae, and the human Ape1 protein (5). ExoIII and Ape1 are the predominant AP endonucleases in E. coli and in humans, respectively, while Apn2 accounts for <10% of the total AP endonuclease activity in yeast. In addition to AP endonuclease activity, ExoIII possesses 3′-phosphatase and 3′-phosphodiesterase activities, and it also has a 3′→5′ exonuclease activity specific for double-stranded DNA (13). Compared to its AP endonuclease activity, Ape1 has a relatively low 3′-phosphodiesterase activity, and Ape1 is most efficient in removing a 3′-PG when it is present at an internal 1-base gap in duplex DNA (10). However, even on this substrate, Ape1 is over 100-fold less efficient in the removal of 3′-PG than the removal of an AP site from duplex DNA (10). Ape1 also displays a very weak 3′→5′ exonuclease activity on duplex DNA (14).

S. cerevisiae Apn2 is a member of a distinct subfamily within the ExoIII/Ape family of proteins, and it more closely resembles the human Ape2 protein than Ape1 (11). Also, S. cerevisiae Apn2, human Ape2, and other members of this subfamily contain a conserved carboxyl-terminal extension that is absent from Ape1 and ExoIII (5, 11). Previously, we purified Apn2 from yeast and showed that it is a class II AP endonuclease (11). Here we examine Apn2 for its ability to remove a 3′-PG from DNA and determine whether it also has a 3′→5′ exonuclease activity. We find that Apn2 contains both these activities. Mutational inactivation of an active-site residue in Apn2 renders cells sensitive to H2O2, indicating the requirement of its 3′-phosphodiesterase activity in the removal of 3′-end groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification of Apn2 protein from yeast.

The wild-type and mutant glutathione S-transferase (GST)–Apn2 proteins were expressed and purified from yeast strain BJ5464 as described elsewhere (11), except that cell breakage buffer and solutions used after the elution step from the gluthathione-Sepharose 4B column contained 0.5 mM EDTA.

DNA substrates.

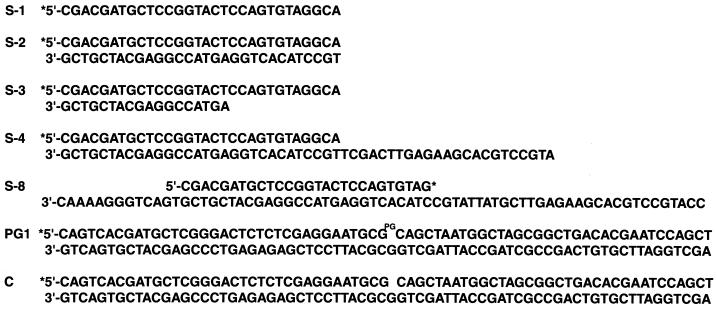

The various DNA substrates used in this study are shown in Fig. 1. A 35-nucleotide (nt) oligomer containing a 3′-PG terminus was synthesized on a 3′-CPG–glycerol support (purchased from Glen Research) at the 1 μM scale on a Perkin-Elmer Biosystems Expedite DNA synthesizer following the procedure of Urata and Akagi (12). The duplex DNA substrate PG1 was constructed by hybridizing the 35-nt oligomer containing a 3′-PG terminus and a 34-nt oligomer to the 70-nt oligomer (see Fig. 1). The oligonucleotides containing the 3′-PG modification were separated from the unmodified forms on a 7 M urea–15% polyacrylamide denaturing gel and were gel purified.

FIG. 1.

DNA substrates used in this study. See the text for further details. The asterisks indicate the radioactively labeled terminus.

Nuclease assays.

Standard exonuclease and phosphodiesterase reaction mixtures (10 μl) contained 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 100 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, and 10% glycerol. Routinely, 200 fmol of 32P-labeled oligonucleotide substrates was used in the reactions with 50 fmol of GST-Apn2 protein. Mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 5 min, and reactions were stopped by the addition of formamide-EDTA gel loading buffer. DNA products were separated on 7 M urea–10% polyacrylamide denaturing gels and quantified by PhosphorImager analysis and ImageQuant Software (Molecular Dynamics, Inc., Sunnyvale, Calif.).

RESULTS

Apn2 catalyzes the removal of the 3′-PG group.

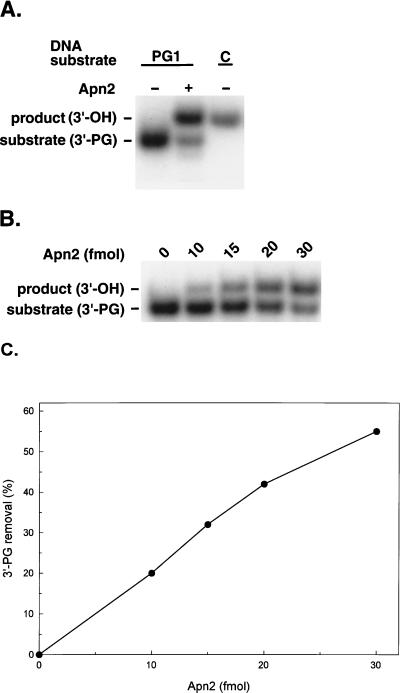

To examine the ability of Apn2 to remove 3′-PG, we used a 70-bp-long DNA substrate PG1 containing a single-strand break at position 35 (Fig. 1). The strand break has a 3′-PG terminus separated by a 1-base gap (Fig. 1). Enzymatic removal of the 3′-PG results in a 3′-hydroxyl terminus (3′-OH), and 3′-PG is released in the form of phosphoglycolic acid (15). The 3′-OH group confers lower electrophoretic mobility to the 35-nt oligomer on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel (10). Incubation of Apn2 protein with the PG1 substrate resulted in the appearance of a lower-mobility band on the gel at the position of the corresponding control substrate C (Fig. 1), in which the 3′ terminus of the 35-nt oligomer has a 3′-OH (Fig. 2A). Conversion of the 3′-PG into the 3′-OH increased linearly with increasing enzyme concentration (Fig. 2B and C). These results indicate that Apn2 has a phosphodiesterase activity.

FIG. 2.

Phosphodiesterase activity of the Apn2 protein. (A) GST-Apn2 protein (50 fmol) was incubated with 200 fmol of PG1 substrate, which contains a 5′-labeled 35-nt DNA strand with a 3′-PG terminus. Lane C represents a control DNA substrate which is the same as PG1 except that the 5′-labeled strand has a 3′-OH end instead of PG. Reactions were carried out for 5 min at 30°C, and the reaction products were analyzed on a 7 M urea–12% polyacrylamide gel. (B) PG1 substrate (200 fmol) was incubated with the indicated amount of GST-Apn2. (C) Graphic representation of results in panel B.

A 3′→5′ exonuclease activity in Apn2.

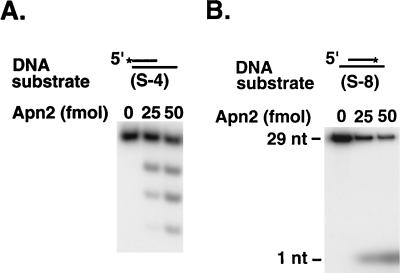

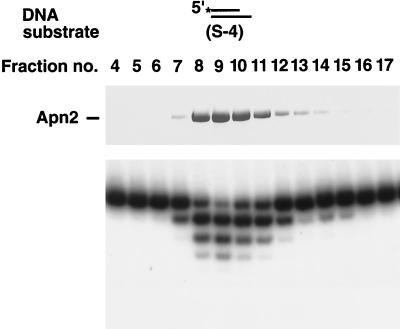

The exonuclease activity of Apn2 was first assayed on a double-stranded DNA substrate containing a 5′-end-labeled strand with a recessed 3′ terminus. Incubation of increasing amounts of Apn2 with this DNA substrate generated a series of smaller products (Fig. 3A), indicating that Apn2 exonucleolytically digested the DNA from the 3′ terminus. In another experiment, we used a double-stranded DNA substrate in which both the 5′ and 3′ termini of the 3′-end-labeled strand were recessed. With this substrate, we could identify the release of a mononucleotide product by Apn2 (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that Apn2 hydrolyzes DNA in the 3′→5′ direction. As shown in Fig. 4, the exonuclease activity copurifies with the Apn2 protein. The strict coelution of the exonuclease activity with Apn2 in the Mini-S chromatography fractions strongly suggested that this activity was intrinsic to the Apn2 protein.

FIG. 3.

Apn2 has a 3′→5′ exonuclease activity. The indicated amounts of GST-Apn2 protein were incubated for 5 min at 30°C with the following substrates: 200 fmol of the S-4 partial DNA duplex containing a 5′-labeled strand with a 3′-recessed terminus (A) and 200 fmol of the S-8 partial DNA duplex containing a 3′-labeled strand with 5′- and 3′-recessed termini (B). The reaction products were analyzed on a 7 M urea–10% polyacrylamide gel (A) and on a 7 M urea–20% polyacrylamide gel (B). DNA bands were visualized by autoradiography. The positions of the uncleaved 29-mer oligonucleotide and the mononucleotide product are shown on the left on Fig. 3B. The asterisk indicates the radioactively labeled terminus. See the legend to Fig. 1 for C-4, S-8, and other DNA substrates used in this study.

FIG. 4.

Coelution of 3′→5′ exonuclease activity with the Apn2 protein. Fractions from the Mini-S chromatography step were assayed for exonuclease activity. (Top) Each fraction (1 μl) was separated on an 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie blue. (Bottom) Fractions were diluted 100-fold and examined for exonuclease activity with the S-4 partial DNA duplex containing a 5′-labeled strand with a 3′-recessed terminus.

The exonuclease activity of Apn2 increases with incubation time for up to 30 min (Fig. 5A), and it shows high activity in the pH range of 7.5 to 8.8 (Fig. 5B) in a reaction buffer containing no salt. Addition of salt inhibits the exonuclease activity, and little activity was observed at NaCl concentrations of 200 mM or higher (Fig. 5C). Apn2 exonuclease is strongly dependent on metal ions and requires magnesium or manganese (Fig. 5D). No exonuclease activity was observed in the absence of these metals or in the presence of calcium, cobalt, or zinc (Fig. 5D). Curiously, the AP endonuclease activity of Apn2 is not affected in the absence of magnesium or other metals (11).

FIG. 5.

Optimal reaction conditions for the exonuclease activity of Apn2 protein. The exonuclease activity of GST-Apn2 was assayed under various conditions, using the S-4 partial DNA duplex substrate. (A) Time dependence; (B) pH dependence (morpholineethanesulfonic acid [MES] was used for pHs 5 and 6, and Tris was used for pHs 6.8, 7.5, 8.0, and 8.8); (C) NaCl concentration dependence; (D) metal ion dependence. The first lane contains reaction mixture without any metal ions in the reaction buffer.

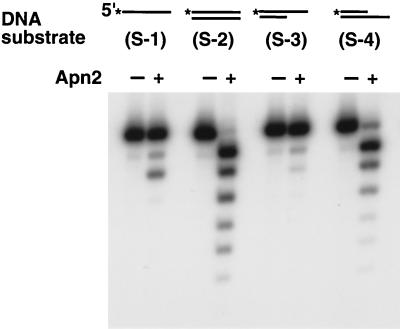

DNA substrate specificity of Apn2 exonuclease.

To determine the DNA substrate requirement for the exonuclease activity, we examined Apn2 for its ability to hydrolyze single-stranded DNA, blunt-ended duplex DNA, or partial DNA duplexes with either a protruding or a recessed 3′ terminus. As shown in Fig. 6, Apn2 is most active on blunt-ended or 3′-recessed double-stranded DNA substrates, whereas much weaker activity was detected with single-stranded DNA and with DNA duplex containing a 3′-protruding terminus.

FIG. 6.

Exonuclease activity of Apn2 protein on different DNA substrates. GST-Apn2 (50 fmol) was incubated with 200 fmol of each of the indicated 5′-labeled DNA substrates for 5 min at 30°C. Lanes − contain a control reaction mixture without any GST-Apn2 protein. Asterisks indicate the radioactively labeled terminus.

Although Apn2 shows significant activity on the single-stranded substrate, the cleavage is not fully progressive. Such an outcome might be expected if the single-stranded substrate folds back and the nuclease cleaves the annealed nucleotides. In agreement with this proposal, Apn2 shows no 3′→5′ exonuclease activity on a homopolymeric oligo(dT) substrate (data not shown), suggesting a high degree of specificity of this activity for double-stranded DNA.

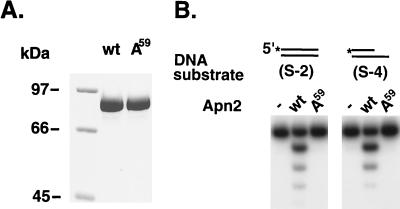

Mutational inactivation of Apn2 3′→5′ exonuclease and 3′-phosphodiesterase activities.

Structural and mutational studies with E. coli ExoIII and human Ape1 have revealed that Glu34 in ExoIII and the equivalent Glu96 in Ape1 play a critical role in metal binding (1, 7, 8). This glutamate residue and the surrounding amino acids are conserved in all members of the ExoIII family of proteins (5, 11). To investigate the requirement of the corresponding glutamate residue, Glu59, in Apn2, we generated a mutant Apn2 protein bearing the Glu59→Ala59 mutation. This Apn2 Ala59 mutant protein, designated A59, was overexpressed and purified to near homogeneity from yeast cells following the same chromatographic procedures as were used for the wild-type protein. During purification, the mutant protein behaved in the same manner as the wild-type protein, and during gel electrophoresis, it migrated to the same position as the wild-type protein (Fig. 7A). The exonuclease activity of A59 was assayed on the two substrates on which wild-type Apn2 protein shows the highest activity: a double-stranded blunt-ended DNA duplex and a partial duplex with a 3′-recessed terminus. In contrast to the proficient degradation of both these substrates by the wild-type Apn2 protein, the A59 mutant protein displayed no activity on either of these substrates (Fig. 7B). Also, unlike the wild-type Apn2 protein (Fig. 2), the A59 mutant protein was unable to remove the 3′-PG terminus (data not shown). These observations indicate that the 3′→5′ exonuclease and 3′-phosphodiesterase activities are intrinsic to Apn2 and that Glu59 in Apn2, just like the equivalent glutamate residue of ExoIII and Ape1, is essential for normal activity.

FIG. 7.

The purity and the activity of the Apn2 Ala59 mutant protein. (A) Two micrograms of the wild-type (wt) and the Ala59 mutant (A59) GST-Apn2 proteins was loaded on an 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie blue. Molecular mass standards with the indicated molecular masses are on the left. (B) The exonuclease activities of the wild-type and mutant GST-Apn2 proteins were compared by using two different DNA substrates. Lanes − contain reaction mixtures without any protein added.

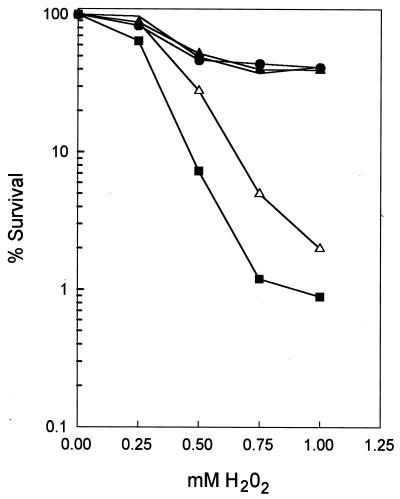

Requirement of Apn2 3′-phosphodiesterase and 3′→5′ exonuclease activities for the removal of 3′-blocked termini.

H2O2 is a common product of oxidative metabolism. The Fenton reaction, which requires H2O2 and a transition metal ion in the reduced form, such as Fe2+, produces a hydroxyl radical (3, 4). OH radicals, formed when DNA-bound Fe2+ reacts with H2O2, often lead to DNA strand breaks that contain a 3′-PG terminus (3, 4). Exposure of E. coli lacking ExoIII to H2O2 results in DNA that contains nicks with 3′ termini that block DNA polymerases, and treatment of such DNA with ExoIII activates it for synthesis by DNA polymerases (2).

As is shown in Fig. 8, although sensitivity to H2O2 is not increased in the apn1Δ or the apn2Δ single mutants, the apn1Δ apn2Δ double mutant strain is strikingly much more sensitive to H2O2 than the single mutants. This suggests that Apn1 and Apn2 provide alternate pathways for the repair of H2O2-induced DNA damage. To determine the role of Apn2 3′-phosphodiesterase activity in the repair of H2O2-induced DNA damage, we introduced plasmid pPM1039, carrying the Ala59 mutation in the APN2 gene, into the apn1Δ apn2Δ strain and examined its H2O2 sensitivity. However, the H2O2 resistance of the apn1Δ apn2Δ strain was not improved by the Apn2 Ala59 mutation (Fig. 8). In fact, the apn1Δ apn2Δ strain carrying the Apn2 Ala59 mutation displays greater H2O2 sensitivity than the apn1Δ apn2Δ strain (Fig. 8). This may be due to unproductive binding of the mutant Apn2 protein to 3′-blocked termini, inhibiting repair by another alternate pathway. Thus, in addition to Apn1 and Apn2, yeast cells may possess a third alternate pathway for the removal of 3′-blocked termini. In summary, our results indicate that the Ala59 mutation, defective in 3′-phosphodiesterase and 3′→5′ exonuclease activities, is unable to repair DNA lesions resulting from H2O2 treatment.

FIG. 8.

Requirement of 3′-phosphodiesterase activity for the repair of H2O2-induced DNA damage. Cells were grown overnight in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose medium (YPD) or in synthetic complete medium lacking leucine (SC-leu) to ensure retention of plasmid pPM1039 carrying the Apn2 Ala59 mutant allele. Cells were diluted in either YPD or SC-leu and incubated at 30°C until they had reached early to mid-exponential phase (density of 5 × 106 to 1 × 107 per ml), at which time 0.5-ml aliquots were treated with H2O2 at 30°C for 1 h with vigorous shaking. Cell suspensions were diluted 10-fold with cold water, and appropriate dilutions were plated on YPD for viability determinations. Each curve represents the average from three or more experiments. Symbols: ●, wild type; ○, apn1Δ; ▴, apn2Δ; ▵, apn1Δ apn2Δ; ▪, apn1Δ apn2Δ cells carrying the Apn2 Ala59 mutant allele in plasmid pPM1039.

DISCUSSION

In the ExoIII/Ape1/Apn2 family of proteins, E. coli ExoIII and human Ape1 have been extensively studied, and both of these enzymes have been shown to possess AP endonuclease, 3′-phosphodiesterase, and 3′→5′ exonuclease activities. Although S. cerevisiae Apn2 has homology with ExoIII and Ape1, the Apn2 proteins of different species are more similar and constitute a new subfamily within the ExoIII/Ape1/Apn2 family. All the proteins in the Apn2 subfamily share the highly conserved motifs in the N terminus involved in metal binding and catalysis, but in addition, the proteins in this subfamily contain a conserved carboxyl-terminal extension absent from ExoIII and Ape1 (5, 11).

We have previously identified a class II AP endonuclease activity in the Apn2 protein of S. cerevisiae (11). In this study we show that like ExoIII, Apn2 is a multifunctional enzyme. It has a 3′→5′ exonuclease activity with a substrate specificity similar to that of ExoIII. Apn2 preferentially hydrolyzes double-stranded DNA substrates and is particularly active on double-stranded blunt-ended DNA and on a partial DNA duplex with a 3′-recessed terminus. Apn2 also catalyzes the removal of a 3′-PG terminus formed in DNA by oxidative agents.

In S. cerevisiae, Apn1 and Apn2 constitute alternate pathways for the removal of AP sites (5). Here, we show that Apn1 and Apn2 play redundant roles in the repair of damage inflicted upon DNA by the oxidative agent H2O2. H2O2 produces DNA strand breaks containing a 3′-phosphate or a 3′-PG terminus, a hallmark of oxidative DNA damage. DNA strand breaks with such 3′-blocked termini impede synthesis by DNA polymerases, and hence, they are refractory to DNA repair synthesis. Although neither the apn1Δ nor the apn2Δ mutation causes an increase in H2O2 sensitivity over that in the wild-type strain, the apn1Δ apn2Δ double mutation confers a large increase in H2O2 sensitivity. The identification of the AP endonuclease activity (11), as well as of the 3′-phosphodiesterase and 3′→5′ exonuclease activities in the yeast Apn2 protein, strongly suggests that Ape2, the human counterpart of yeast Apn2, would also possess all these activities. Our findings that Apn1 and Apn2 provide alternate pathways for the removal of AP sites and for the removal of 3′-end groups such as the 3′-PG termini further suggest that human Ape2 protein would also function in the repair of these various DNA lesions.

To confirm that the 3′-phosphodiesterase or 3′-exonuclease activities of Apn2 are responsible for the repair of 3′-blocked ends formed in DNA by oxidative DNA-damaging agents, we altered the conserved Glu59 residue in Apn2 to Ala59. This acidic residue in Apn2 is equivalent to Glu34 in ExoIII and Glu96 in Ape1 shown previously to be involved in metal binding. As expected, the Apn2 Ala59 mutant protein has no 3′-phosphodiesterase or 3′-exonuclease activity, and this mutation is unable to ameliorate the H2O2 sensitivity of the apn1Δ apn2Δ strain. From these observations, we conclude that there is a role for the 3′-phosphodiesterase activity of Apn2 in the removal of 3′-blocked ends formed in DNA upon treatment with H2O2 and other oxidative DNA-damaging agents.

Apn1 constitutes >90% of the AP endonuclease activity in yeast cells and plays a more significant role in the repair of AP sites than Apn2 (5), as indicated by the fact that the apn1Δ strain exhibits a higher level of sensitivity to methyl methane sulfonate and is also much slower in the removal of AP sites than the apn2Δ strain. Apn1 and Apn2, however, play equally important roles in the repair of H2O2-induced DNA damage, as cells exhibit H2O2 sensitivity only in the absence of both these proteins. These genetic results are consistent with our estimation that the 3′-phosphodiesterase and 3′-exonuclease activities of Apn2 are 30- to 40-fold more active than its AP endonuclease activity. Also, in this regard, Apn2 differs from the human Ape1 protein, which has a much weaker 3′-phosdiesterase or 3′-exonuclease activity than AP endonuclease activity (10, 14). Thus, in humans, we expect Ape2 to play a more dominant role in the repair of oxidative DNA damage than Ape1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Department of Energy grant DE-FG03–00ER62910 and by National Institutes of Health grant CA41261.

We thank R. Hodge for the oligomer containing a 3′-PG terminus, the synthesis of which was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Science grant P30-ES06676.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barzilay G, Mol C D, Robson C N, Walker L J, Cunningham R P, Tainer J A, Hickson I D. Identification of critical active-site residues in the multifunctional human DNA repair enzyme HAP1. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:561–568. doi: 10.1038/nsb0795-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demple B, Johnson A, Fung D. Exonuclease III and endonuclease IV remove 3′ blocks from DNA synthesis primers in H2O2-damaged Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7731–7735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henle E S, Linn S. Formation, prevention, and repair of DNA damage by iron/hydrogen peroxide. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19095–19098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imlay J A, Linn S. DNA damage and oxygen radical toxicity. Science. 1988;240:1302–1309. doi: 10.1126/science.3287616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson R E, Torres-Ramos C A, Izumi T, Mitra S, Prakash S, Prakash L. Identification of APN2, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog of the major human AP endonuclease HAP1, and its role in the repair of abasic sites. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3137–3143. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindahl T, Nyberg B. Rate of depurination of native deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1972;11:3610–3617. doi: 10.1021/bi00769a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mol C D, Izumi T, Mitra S, Tainer J A. DNA-bound structures and mutants reveal abasic DNA binding by APE1 DNA repair and coordination. Nature. 2000;403:451–456. doi: 10.1038/35000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mol C D, Kuo C-F, Thayer M M, Cunningham R P, Tainer J A. Structure and function of the multifunctional DNA-repair enzyme exonuclease III. Nature. 1995;374:381–386. doi: 10.1038/374381a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seeberg E, Eide L, Bjorås M. The base excision repair pathway. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:391–396. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suh D, Wilson III D M, Povirk L F. 3′-Phosphodiesterase activity of human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease at DNA double-strand break ends. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2495–2500. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unk I, Haracska L, Johnson R E, Prakash S, Prakash L. Apurinic endonuclease activity of yeast Apn2 protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22427–22434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002845200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urata H, Akagi M. A convenient synthesis of oligonucleotides with a 3′-phosphoglycolate and 3′-phosphoglycaldehyde terminus. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:4015–4018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace S. Oxidative damage to DNA and its repair. In: Scandalios J G, editor. Oxidative stress and the molecular biology of antioxidant defenses. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 49–90. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson D M, III, Takeshita M, Grollman A P, Demple B. Incision activity of human apurinic endonuclease (Ape) at abasic site analogs in DNA. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16002–16007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.27.16002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winters T A, Henner W D, Russell P S, McCullough A, Jorgensen T J. Removal of 3′-phosphoglycolate from DNA strand-break damage in an oligonucleotide substrate by recombinant human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1866–1873. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.10.1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]