Abstract

Exposure to the ultraviolet (UV) radiation in sunlight creates DNA lesions, which if left unrepaired can induce mutations and contribute to skin cancer. The two most common UV-induced DNA lesions are the cis-syn cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) and pyrimidine (6–4) pyrimidone photoproducts (6–4PPs), both of which can initiate mutations. Interestingly, mutation frequency across the genomes of many cancers is heterogenous with significant increases in heterochromatin. Corresponding increases in UV lesion susceptibility and decreases in repair are observed in heterochromatin versus euchromatin. However, the individual contributions of CPDs and 6–4PPs to mutagenesis has not been systematically examined in specific genomic and epigenomic contexts. In this study, we compared genome-wide maps of 6–4PP and CPD lesion abundances in primary cells and conducted comprehensive analyses to determine the genetic and epigenetic features associated with susceptibility. Overall, we found a high degree of similarity between 6–4PP and CPD formation, with an enrichment of both in heterochromatin regions. However, when examining the relative levels of the two UV lesions, we found that bivalent and Polycomb-repressed chromatin states were uniquely more susceptible to 6–4PPs. Interestingly, when comparing UV susceptibility and repair with melanoma mutation frequency in these regions, disparate patterns were observed in that susceptibility was not always inversely associated with repair and mutation frequency. Functional enrichment analysis hint at mechanisms of negative selection for these regions that are essential for cell viability, immune function and induce cell death when mutated. Ultimately, these results reveal both the similarities and differences between UV-induced lesions that contribute to melanoma.

Keywords: UV susceptibility, 6–4PP, UV-induced mutations, melanoma, excision repair, CPD

1. Introduction

Ultraviolet radiation (UV) is the most abundant carcinogen in our environment and is the primary risk factor for skin cancer development (F.R. de Gruijl, 1999). UV radiation induces the formation of bulky, helix disrupting DNA lesions that interfere with DNA replication and transcription, and if left unrepaired can lead to cytotoxicity or mutagenesis. The two most abundant UV-induced DNA lesions are the cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD) and the pyrimidine (6–4) pyrimidone photoproduct (6–4PP) (Ravanat et al, 2001). CPD lesions are formed when a cyclobutane ring is formed between the C5 and C6 positions of two adjacent pyrimidine bases, whereas 6–4PPs are formed by a single covalent bond between the C6 of the 5’ end and the C4 position of two adjacent pyrimidines (Mitchell and Nairn, 1989). Upon formation, these DNA lesions induce distortions within the local DNA double helix. For instance, CPD lesions induce a 9° bend in DNA causing minor helical distortions, whereas 6–4PP lesions induce an even greater 44° bend (Kim et al, 1995). CPD lesions generally form approximately 3–5 times more often compared to 6–4PP lesions (You et al, 2001), however formation frequencies are strongly dependent on DNA sequence context.

The presence of bulky UV lesions can interfere with important cellular processes like transcription and replication, which can potentially compromise genome stability and cell viability (Balajee & Bohr, 2000). To circumvent the adverse effects caused by DNA lesions, cells utilize nucleotide excision repair (NER) machinery to remove 6–4PPs and CPDs using two distinct sub-pathways with varying efficiencies (Marteijn et al, 2014). The global genome NER (GG-NER) pathway probes the genome for bulky DNA lesions whereas the transcription-coupled NER (TC-NER) pathway activates when lesions stall RNA polymerase II during elongation. 6–4PPs are recognized with higher affinity by the GG-NER pathway due to the higher helix disrupting structure of 6–4PPs and are generally repaired with higher efficiency than CPDs. CPD lesions, which only induce minor helical disruptions, are detected more efficiently on the template strand by the TC-NER pathway.

UV radiation induces distinct C>T and CpC>TpT mutations (also called UV signature) at di-pyrimidine sequences and are also the most prevalent mutation type observed in sun-exposed skin cancers, such as cutaneous melanoma (Brash et al, 1991; Hayward et al, 2017). In fact, skin cancers have one of the highest somatic mutation loads of any cancer (Alexandrov et al, 2013). However, elucidating the relative mutagenic contribution of 6–4PPs and CPDs in skin cancer has remained a longstanding question in the field. Both 6–4PP and CPD lesions can induce mutations, which can vary depending on the sequence. For example, 6–4PP lesions are highly mutagenic at TpT sites in E. coli (LeClerc et al, 1991) inducing T>C transitions at the 5’-T. At TpC sequences, 6–4PP and CPD lesions have each been reported to induce C>T mutations in genetic studies using reporter constructs containing site-specific UV lesions (Horsfall and Lawrence, 1994; Horsfall et al, 1997). In a study using transgenic mutation reporter genes to measure the relative contributions of each UV lesion, the authors concluded that ~80% of UV-induced mutations in mammalian cells were caused by CPDs (You et al, 2001). Although CPD lesions are likely a major contributor to melanoma mutations due to their high abundance and slow repair, 6–4PP lesions may still contribute to the mutational spectrum in melanoma.

UV-induced mutations result from a complex process that involves DNA damage formation, inadequate repair and errors during replication, all of which occur within a dynamic chromatin landscape. Chromatin plays a critical role in regulating proper gene expression and maintaining genome integrity by spatially organizing the genome into structurally and functionally distinct euchromatic and heterochromatic compartments. Heterochromatin, enriched for trimethylated histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3), are highly compact regions in the genome with significantly elevated somatic mutation frequency (Polak et al, 2015; Schuster-Böckler et al, 2012). Recent studies demonstrate that NER is more active in gene-rich euchromatic regions, whereas sites with the lowest repair are heterochromatic regions (Hu et al, 2015; Adar et al, 2016).

Not only is DNA sequence an important factor for UV lesion formation frequencies, but nucleosomes and other DNA binding proteins also modulate lesion formation (Mao et al, 2017). Early studies using UV irradiated chromatin fibers found that CPD distributions displayed a 10.3 base periodicity within nucleosomal DNA but were randomly distributed in linker regions. Interestingly, 6–4PP lesions form 6-fold more frequently in linker DNA compared to core nucleosome DNA (Mitchell et al, 1990b). More recently, studies analyzing genome-wide distribution of CPD lesions revealed that regions most susceptible to CPD formation disproportionately occur within LINE repeat-enriched heterochromatin located near the nuclear periphery (García-Nieto et al, 2017). These recent studies have demonstrated that chromatin can modulate UV lesion formation and repair, however a similar study has not been conducted to investigate the factors regulating 6–4PP formation and to what extent 6–4PP lesions contribute to skin cancer development.

In this study we sought to delineate the epigenetic and genetic factors associated with 6–4PP susceptibility and potential contributions to mutagenesis in melanoma. In addition, we compare the relative distributions between 6–4PP and CPD lesions across the genome and within distinct epigenomic states. Comparative analyses revealed distinct regions that are uniquely more susceptible to either 6–4PP or CPD formation. In addition, we integrate both susceptibility and repair information for each lesion in order to determine mutagenic potential across the genome. Comparisons with mutation frequency in melanoma reveal possibilities for disproportionate contributions of either susceptibility or repair at different genomic loci and may suggest mechanisms of selective pressure during carcinogenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell culture and UV treatment

IMR-90 primary lung fibroblast cells were grown to 60–80% confluence and were treated with 100 J/m2 UVC followed by immediate lysis with buffer containing 1% SDS. Irradiated DNA was purified and isolated with RNase and proteinase K treatment followed by ethanol/sodium acetate precipitation. Purified DNA was fragmented through sonication using a Bioruptor (Diagenode) and single-strand DNA was incubated with anti-6–4PP antibody (64M-2 from Cosmo Bio USA). Immunoprecipitated DNA fragments were repaired using lesion specific photolyases for 6–4PP and CPD lesions (Selby and Sancar, 2006) and subsequently prepped for sequencing.

2.2. Library preparation and sequence processing

Libraries were prepared for sequencing with Illumina HiSeq using second-strand DNA synthesis, end repair, and adapter ligation with NEBNext Directional Second-Strand Synthesis (cat. No. E7550) and ChIP-seq Library Prep Master Mix for Illumina (cat. No. E6240). Sonicated DNA was used as the Input control and was prepared for sequencing. Data processing was conducted using specifications for the ENCODE (phase-3) transcription factor and histone ChIP-seq pipeline (ENCODE Project Consortium et al, 2012). Sequenced reads were mapped to the reference human genome (hg19) using Bowtie2 version 2.2.6. Technical replicates for 6–4PP and Input control were pooled together to generate fold change (IP/Input) bigWig signal track files using MACS2.0. Genome-wide map of CPD damage in IMR-90 cells was previously published in García-Nieto et al, 2017 and is available at GSE94434.

2.3. Rank normalization of UV lesion signals

A rank-based inverse normal transformation (INT) method was used to transform each UV lesion distribution to fit a standard normal distribution. 6–4PP and CPD fold change (IP/Input) signals (100kb and 1Mb bin size) were mapped to a probability scale and replaced with fractional ranks, and subsequently transformed into z-scores using the quantile function (qnorm) in R (Beasley and Erickson, 2009). To measure the relative difference in susceptibility, rank normalized CPD signals were subtracted from normalized 6–4PP signals within a genomic region (6–4PP – CPD).

2.4. Genomic analyses

CPD and 6–4PP fold change (IP/Input) signals were calculated over 100kb and 1Mb regions using, where designated, the mean. Genomic coordinates for repetitive elements were obtained by RepeatMasker version 4.0.5 (Smit, AFA, Hubley, R & Green, P. RepeatMasker Open-4.0. 2013–2015; http://www.repeatmasker.org). Annotations for genic features (1 to 5kb, promoter, 5’UTR, exon, intron, 3’UTR, and intergenic) were obtained from UCSC’s KnownGene database (https://genome.ucsc.edu/; Hsu et al, 2006). Gene coordinates were retrieved from Ensembl database v75 for hg19 (http://www.ensembl.org/) and were limited to include protein coding genes. Annotations for predicted enhancer and enhancer-target genes for IMR-90 cells were obtained from the EnhancerAtlas database (http://www.enhanceratlas.org/) (Gao and Qian, 2019; Gao et al, 2020). Coordinates for super-enhancer regions for IMR-90 were downloaded from the dbSUPER database (http://bioinfo.au.tsinghua.edu.cn/dbsuper/; Khan and Zhang, 2015) and were first characterized by Hnisz et al, 2013 using a H3K27ac ChIP-seq signal based ranking method. Analysis to test for over-representation (enrichment) and under-representation (depletion) of genomic features within indicated regions was conducted using a hypergeometric test. Enrichment was determined by measuring the probability of observing an equal or greater number of base-pair overlap between one set of genomic features and regions of interest than would be expected due to random chance, whereas depletion was determined by measuring the probability of observing an equal or fewer than number of base-pairs that would be expected due to random chance.

2.5. Epigenome analyses

A 15 chromatin state model was previously defined for IMR-90 using the multivariate Hidden Markov Model (HMM) which used multiple epigenetic features including DNase I hypersensitivity (HS), DNA methylation, a “core” set of five histone marks consisting of H3K4me3, H3K4me1, H3K36me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3 with an additional 21 histone marks (Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium et al, 2015). State coordinates and signal track files for individual chromatin features were downloaded from the project web portal (http://egg2.wustl.edu/roadmap/web_portal/). In addition to the 26 histone marks available from the Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium, ChIP-seq data for H4K20me3 was obtained from Nelson et al, 2016 and were reprocessed using the same pipeline used by Roadmap Epigenomics to conform with the same standards. UV lesion signal was calculated for each chromatin state using the mean and normalized using the median fold change (IP/Input) signal of the whole genome. Log2 (fold change) signals for each state were pooled to visualize distributions across all chromatin states. To measure differences between 6–4PP and CPD susceptibilities within each chromatin state, UV lesion signals binned by chromatin states of variable size were rank normalized as previously described in Materials and Methods. Normalized CPD signals were then subtracted from normalized 6–4PP signal within each chromatin state. Lamin B1 signal (log2 binding ratio) was determined using a lamin B1-DamID chimeric protein to map interaction sites in the genome (Guelen et al, 2008). Normalized Lamin B1 data was downloaded and consolidated into one file from accession GSE8854 and genomic coordinates were converted from hg18 to hg19 using UCSC’s liftOver tool. Analyses with individual chromatin features were conducted by measuring the mean signal over 1Mb genomic regions. Heatmap of epigenetic feature abundance per chromatin state was the log2 (mean fold change per state) normalized by the genome mean.

2.6. Principle component analysis

Principle component analysis (PCA) was conducted using the mean signal (log2(fold change)) for 6–4PP and CPD lesions, and all chromatin marks and lamin B1 within 1Mb bins. PCA was done using the prcomp function in R with center and scale = TRUE. To assess the contribution of each principle component the values of each principle component were correlated back to the values of every individual feature.

2.7. 3D genome modeling

Chrom3D (https://github.com/CollasLab/Chrom3D) was used to generate a 3D genome structure model of the IMR-90 nucleus where chromosomes are modeled as chains of connected beads and represent topologically-associated domains (TADs) (Paulsen et al, 2017, 2018). TAD-TAD contact maps from Hi-C data (Rao et al, 2014) and TAD-lamina interactions from Lamin B1-DamID data (Guelen et al, 2008) for IMR-90 cells were used to determine the relative proximity of TADs with each other and to the nuclear periphery, respectively. In 3D model, TADs with a minimum of 10% overlap with top or bottom susceptible 100kb bins are highlighted, resulting in >89% representation of top/bottom susceptible regions.

2.8. Melanoma mutation analyses

Mutation rates were calculated by obtaining single base substitution data for 136 cutaneous melanoma cancer genomes, characterized predominantly by UV-associated mutation signatures (Hayward et al, 2017). Mutation data was downloaded from the International Cancer Genome Consortium Data Coordination Centre (https://dcc.icgc.org/releases/current/Projects/MELA-AU). For mutation rate analyses, melanoma mutation rates were calculated by counting all C>T and G>A substitutions within non-overlapping regions of equal length (100kb or 1Mb bin sizes) or variable length (genes and enhancers). Mutation rates were normalized by cytosine and guanine content from the hg19 reference genome within each bin. Correlation analyses with mutation rates and UV lesions were conducted by normalizing UV lesions by TpT content, the most frequently occurring di-nucleotide sequence in raw CPD and 6–4PP sequencing files. Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient was used to determine correlation. A consolidated list of melanoma cancer driver genes (Supplemental File S1) was compiled from the Catalog of Somatic Mutations (COSMIC) Cancer Gene Census catalog (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic), the PanCancer Driver Gene list from Bailey et al, 2018 as part of the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), and the IntOGen cancer driver database release 2014.12 (www.intogen.org) (Gonzalez-Perez et al, 2013).

2.9. Nucleotide excision repair analyses

Excision repair rates for both types of UV lesions were measured in normal human fibroblast (NHF1) cells using eXcision Repair-sequencing (XR-seq), which sequences DNA fragments released from TFIIH in response to nucleotide excision repair processes (Adar et al, 2016). Repair datasets were downloaded from GSE76391 and contain strand-specific measurements that include six time points (1h, 4h, 8h, 16h, 24h, and 48h) for CPD lesions and five time points (5min, 20min, 1h, 2h, and 4h) for 6–4PP lesions.

Replicates and strand-specific XR-seq signal track values (reads normalized by sequencing depth) were averaged together for all analyses. Repair rates on the X-chromosome were removed from all analyses due to the indistinguishable and potentially different repair kinetics occurring on the transcriptionally active and inactive X-chromosomes. Cumulative excision repair levels were calculated by adding repair rates for all time measurements together for each UV lesion, respectively. For whole genome repair analyses, cumulative excision repair levels were measured by calculating the mean repair signal over indicated regions. For chromatin state, gene and enhancer repair analyses, XR-seq reads were filtered to only include reads (25 bp) that uniquely mapped to the genome within 24 bp using wgEncodeCrgMapabilityAlign24mer.bigWig downloaded from http://hgdownload.soe.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/encodeDCC/wgEncodeMapability/. Chromatin states, protein coding genes and enhancer regions with cumulative repair levels > 0 were included in analyses. Due to the variable bin sizes of each chromatin state, cumulative repair signals were normalized by dividing by the total count of all di-pyrimidine sequences (TpT, TpC, CpT and CpC on the forward stand, and ApA, GpA, ApG and GpG on the reverse strand) within each bin, respectively. UV susceptibility/excision repair ratio scores were measured in protein coding genes and enhancers that overlapped with at least 50% with 100kb binned regions.

2.10. Functional enrichment analysis

Enrichment analysis was conducted using the online tool Enrichr (Mount Sinai Innovation Partners, https://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/Enrichr/) (Chen et al, 2013; Kuleshov et al, 2016). Gene-set databases included the three core Gene Ontology libraries (biological process, molecular function and cellular component) (Ashburner et al, 2000) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (Ogata et al, 1998) for pathway enrichment. Enrichment values are the negative log10 transformed q-value, which is an adjusted p-value using the Benjamini-Hochberg method for correction of multiple hypothesis testing.

2.11. Data availability

Raw sequencing and signal track files generated in this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession number GSE157070). All code used in this study is available at our github repository (https://github.com/MorrisonLabSU).

3. Results

3.1. Genome-wide levels of 6–4PP are enriched in heterochromatin and correlated with CPD lesions

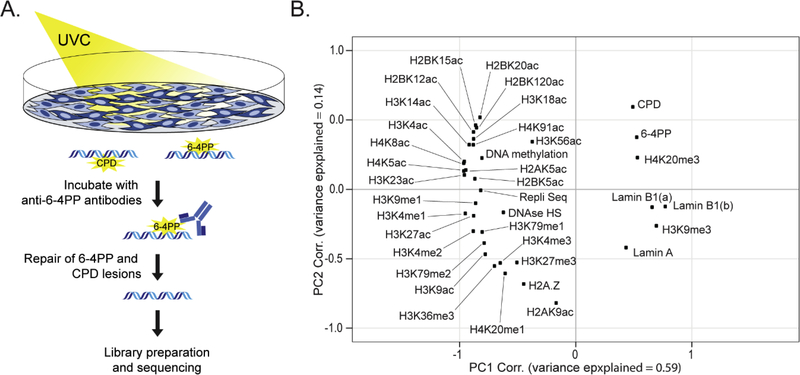

To investigate the genomic and epigenetic features associated with 6–4PP susceptibility, we first generated a genome-wide map of UV-induced 6–4PP damage. Briefly, cells were exposed to less than 10 seconds of UV light (100 J/m2), followed by immediate cell lysis. Purified DNA was subsequent immunoprecipitation (IP) with 6–4PP specific antibodies, repaired in vitro, and prepped for sequencing (Fig. 1A). Di-pyrimidine analysis of raw sequencing reads revealed an enrichment of TpT and TpC (Supp. Fig. 1A), in agreement with previous in vitro analysis of 6–4PP di-pyrimidine propensity (Douki and Cadet, 2001). Analysis of replicates at different bin sizes identified a Pearson correlation (r) ≥ 0.85 at 100kb bins or larger (Supp. Fig. 1B), indicating broad distribution of lesions across the genome.

Fig 1: Genome susceptibility patterns are similar between 6–4PP and CPD lesions.

(A) Experimental workflow of genome-wide mapping of 6–4PP lesions. IMR-90 cells were irradiated with 100 J/m2 UVC and immediately lysed. Purified DNA was then fragmented and immunoprecipitated using 6–4PP specific antibodies, followed by repair of CPDs and 6–4PP lesions prior to Illumina sequencing. (B) Principle component (PC) analysis of genome-wide abundances of 6–4PP, CPD lesions and epigenetic features for IMR-90 cells within 1MB bins (ENCODE Project et al, 2012; Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium et al, 2015; Nelson et al, 2016). Lamin A and two lamin B1 datasets (a and b) were previously defined (Lund et al, 2014; a, Sadaie et al, 2013; b, Guelen et al, 2008).

In order to uncover epigenetic patterns of 6–4PP susceptibility on a genome-wide scale, 6–4PP levels were compared with a comprehensive set of chromatin features previously characterized for IMR-90 cells (Guelen et al, 2008; Sadaie et al, 2013; Lund et al, 2014; Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium et al, 2015; Nelson et al, 2016; García-Nieto et al, 2017). Principle component (PC) analysis reveals that PC1 explains a majority of the variance and that 6–4PP abundance associates with patterns of CPD lesion susceptibility, repressive histone modifications (H4K20me3 and H3K9me3), and lamin A and lamin B1 binding sites compared with euchromatic features (Fig. 1B). Correlation analysis with individual features revealed that 6–4PP lesions negatively correlate with DNase I HS sites (r = −0.39) and histone marks associated with active transcription, such as H3K36me3 (r = −0.45) and H3K4me3 (r = −0.34) (Supp. Fig. 1C). Conversely, histone modifications associated with constitutive and facultative heterochromatin, such as H3K9me3, H4K20me3, H3K27me3, were positively associated with 6–4PP abundance (r = 0.24, 0.47, and 0.47, respectively) (Supp. Fig. 1D). Taken together, epigenomic patterns of 6–4PP susceptibility was found to be broadly similar to that of CPD susceptibility (García-Nieto et al, 2017; Hu et al, 2017), with both preferentially forming in lamina-associated heterochromatin.

3.2. Genetic and epigenetic composition of regions with higher 6–4PP susceptibility

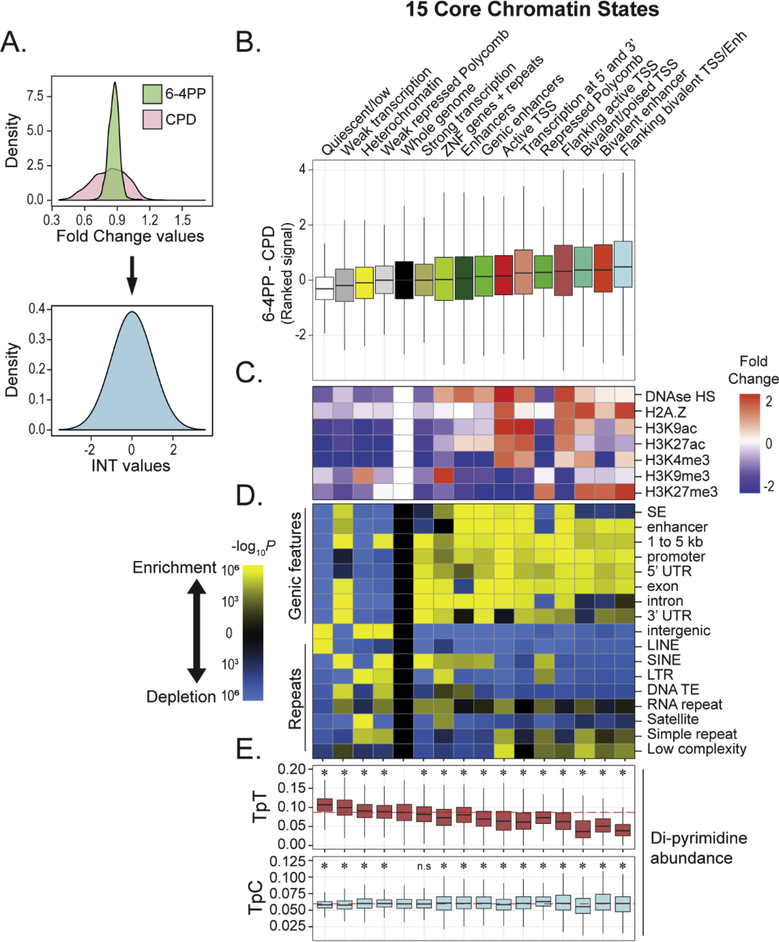

Despite the similarities between 6–4PP and CPD distributions, we sought to identify regions of the genome that preferentially form higher levels of 6–4PP lesions compared to CPDs and vice versa. In order to normalize the signal distribution between the 6–4PP and CPD datasets, we applied a rank-based inverse normal transformation (INT) (Fig. 2A) (Beasley and Erickson, 2009). Genome-wide analyses demonstrate that the transformed and non-transformed datasets are well correlated (Supp. Fig. 2A and B).

Fig 2: Genomic and epigenetic profiles of chromatin regions more susceptible to 6–4PP versus CPD.

(A) Rank-based inverse normal transformation (INT) of genome-wide 6–4PP and CPD fold change (IP/input) signals. Overlap of 6–4PP and CPD fold change (IP/Input) signal prior to rank normalization (top) and rank normalized standard distributions (bottom) are shown. (B) Distribution of susceptibility differences between 6–4PP and CPD lesions (6–4PP – CPD) within 15 previously defined chromatin states for IMR-90 (Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium et al, 2015). (C) Heatmap depicting mean log2[fold change (IP/input)/mean genome fold change] of representative epigenetic features in each state. (D) Heatmaps depicting significance of enrichment (yellow) and depletion (blue) of genic features (top) and repetitive elements (bottom) within each chromatin state. SE is super enhancer. DNA transposable element is DNA TE. A hypergeometric test was used to measure significant [−log10(P)] over-representation (enrichment) or under-representation (depletion). (E) TpT and TpC di-pyrimidine frequencies within each state. Significance was determined using a permutation test comparing the median di-pyrimidine frequency from a randomly sampled group of and median di-pyrimidine frequency each chromatin state. * P < 0.01.

Differences between 6–4PP and CPD susceptibilities were first examined within predefined chromatin states that represent diverse biological functions and epigenetic features (Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium et al, 2015). As expected, and previously reported, preferential formation of either 6–4PP or CPD is observed in heterochromatin versus euchromatin states (García-Nieto et al, 2017; Hu et al, 2017) (Supp. Fig. 2C and D). However, bivalent/poised chromatin states preferably form 6–4PPs compared to CPDs (Fig. 2B). Proximal promoter regions flanking active transcriptional start sites and repressed Polycomb states also had higher relative susceptibility levels for 6–4PP lesions. Bivalent chromatin states contain both “activating” and “repressing” histone modifications such as H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 at loci “poised” for activation during specific developmental timing whereas Polycomb repressed states only contain H3K27me3 (Harikumar and Meshorer, 2015) (Fig. 2C). In addition, regions with higher relative levels of 6–4PP were significantly enriched for enhancers and many genic features, including distal promoters (1 to 5kb), promoters, and exons (Fig. 2D). Conversely, regions that are enriched in both CPDs and 6–4PPs are heterochromatin-associated intergenic sequences containing repeat sequences, such as LINEs and SINEs (Fig 2D, and Supp. Fig. 2E and F).

To assess if di-pyrimidine abundance may contribute to the observed susceptibility patterns, we measured the frequency of TpC and TpT di-pyrimidines for all chromatin states. In terms of yield, CPDs form approximately ten times more often than 6–4PPs at TpT sites. Interestingly, both 6–4PP and CPD lesions form at TpC sites in equal amounts (Douki and Cadet, 2001; Mitchell et al, 1990a), making 6–4PP lesions at TpC the third most common UV-induced lesion. Indeed, we found that TpT frequency is inversely correlated with chromatin states with relatively higher 6–4PP levels (Fig. 2E), indicating that the observed pattern may be due to a decrease in TpT sequences most optimal for CPD formation. We also observed significantly higher levels of TpC sequences in the top 10% regions more susceptible to 6–4PP than CPDs, and higher levels of TpT in regions more susceptible to CPD than 6–4PP (bottom 10% 6–4PP – CPD) (Supp. Fig. 2G and H). This suggests that di-pyrimidine sequence frequency is linked to the differences in susceptibility between 6–4PP and CPD lesions.

As mentioned, we previously demonstrated that regions highly susceptible to CPD formation are LINE-rich heterochromatin located at the nuclear periphery (García-Nieto et al, 2017). In order to investigate the radial position of regions that are more susceptible to 6–4PP formation, we examined susceptibility across individual chromosomes with radial positioning data previously determined by Bolzer et al, 2005. Although both 6–4PP and CPD separately correlate with radial positioning (r = 0.68 and r = 0.6, respectively), and as previously reported for CPDs (García-Nieto et al, 2017), no significant correlation between 6–4PP – CPD ranked differences and spatial chromosome organization were identified (Supp. Fig. 3A). In order to assess susceptibility at a higher resolution, we utilized Chrom3D, a modeling program for 3D positioning of topologically-associated domains (TADs) (Paulsen et al, 2017, 2018). We found that top 10% 6–4PP and CPD susceptible regions localized closer to the nuclear periphery compared to relatively protected regions in the center of the nucleus (Supp. Fig. 3B and C), consistent with previously published results (García-Nieto et al, 2017). Interestingly, regions more susceptible to 6–4PP formation (top 10% 6–4PP – CPD) were closer to the nuclear interior compared to regions more susceptible to CPD formation at the exterior (bottom 10% 6–4PP-CPD).

In summary, this data demonstrates that global levels of 6–4PP and CPDs are enriched in heterochromatin regions at the nuclear periphery, while bivalent genic and enhancer regions are uniquely more susceptible to 6–4PP and are located more proximal to the nuclear interior.

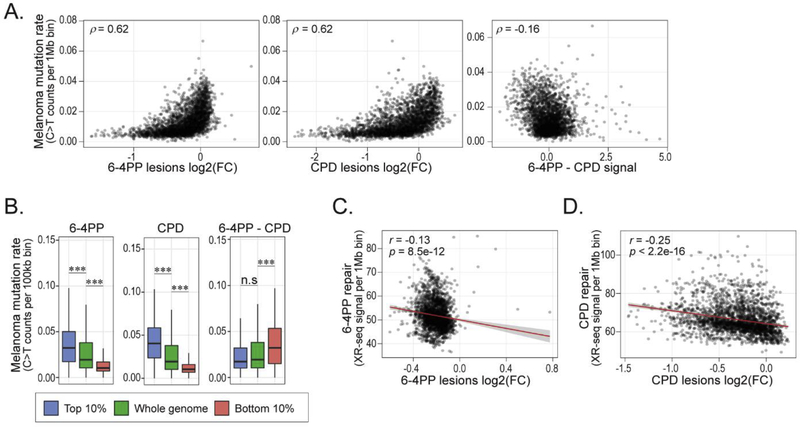

3.3. Genome-wide correlations between susceptibility, repair and mutation frequency

As mentioned, cytosine to thymine nucleotide substitutions are the most prevalent somatic mutation observed in cutaneous melanomas and is attributed to UV radiation (Hodis et al, 2012; Alexandrov et al, 2013; Hayward et al, 2017). Across the genome, 6–4PP levels positively correlate with melanoma C>T mutation density (Spearman’s rho (ρ) = 0.62, Fig. 3A), and were comparable to CPD results previously published (García-Nieto et al, 2017). The distribution of UV lesion susceptibility differences (6–4PP – CPD) showed a subtle but significantly negative correlation with melanoma mutation rates (ρ= −0.16). Accordingly, regions of the genome with the highest susceptibility (top 10%) to either 6–4PP or CPD formation exhibited significantly higher mutation rates, while the regions with the lowest susceptibility exhibited significantly lower rates (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, regions in the genome more susceptible to 6–4PP lesions than CPDs did not have significantly different mutation rates compared to the genome median, whereas regions with higher relative CPD levels (bottom 10% 6–4PP – CPD) were significantly more mutated than the rest of the genome.

Fig 3: 6–4PP and CPD lesion susceptibility positively correlates with increased mutation rate and negatively correlates with excision repair.

(A) Scatterplots comparing genome-wide C>T mutation rates (C>T rate + G>A rate) from cutaneous melanoma samples (Hayward et al, 2017) and 6–4PP (left), CPD (middle) lesion abundance [log2 fold change (FC) IP/input] and differences in UV susceptibility (6–4PP – CPD, right) within 1Mb windows. Scatterplot contains Spearman’s rho (ρ) correlation value. (B) Distribution of total C>T mutation rates within top and bottom 10% 6–4PP, CPD and 6–4PP-CPD compared to median genome mutation rate. Wilcoxon rank sum test: n.s = not significant, ***P < 0.0001. (C-D) Scatterplots comparing genome-wide 6–4PP (C) and CPD (D) abundance [log2 fold change (FC) IP/input] with cumulative repair levels of the same lesion type at 1Mb bin size. Scatterplots include Pearson’s correlation (r) and significance value (p). Shaded gray indicates 95% confidence interval and linear regression line is shown in red.

Mutations are contributed by both susceptibility and repair efficiency. To better understand how mutation frequency is influenced by excision repair activity and susceptibility across different chromatin states, we compared previously published (Adar et al, 2016) NER data for 6–4PP and CPD lesions and acute UV damage susceptibility generated in this project and previously published (García-Nieto et al, 2017). Cumulative repair was measured by adding the repair counts from all time points for each lesion type (see Materials and Methods) Consistent with previous results (Adar et al, 2016; Balajee et al, 2000), cumulative repair levels for either 6–4PP or CPD were highest in chromatin states characterized by active and poised transcription demarcated by elevated levels of active chromatin marks, whereas repressed and heterochromatic states had the lowest repair levels (Supp. Fig. 4).

We thus wanted to determine the relationship between 6–4PP and CPD susceptibility with cumulative levels of repair across the genome (1Mb bins). We hypothesized that 6–4PP and CPD levels would negatively correlate with repair due to the high abundance of both lesions in heterochromatin, which is also characterized by slow repair (Adar et al, 2016). Indeed, genome-wide correlation analysis revealed subtle, yet statistically significantly, negative associations between excision repair and susceptibility for both 6–4PP (r = −0.13) and CPD (r = −0.26) (Fig. 3C and D).

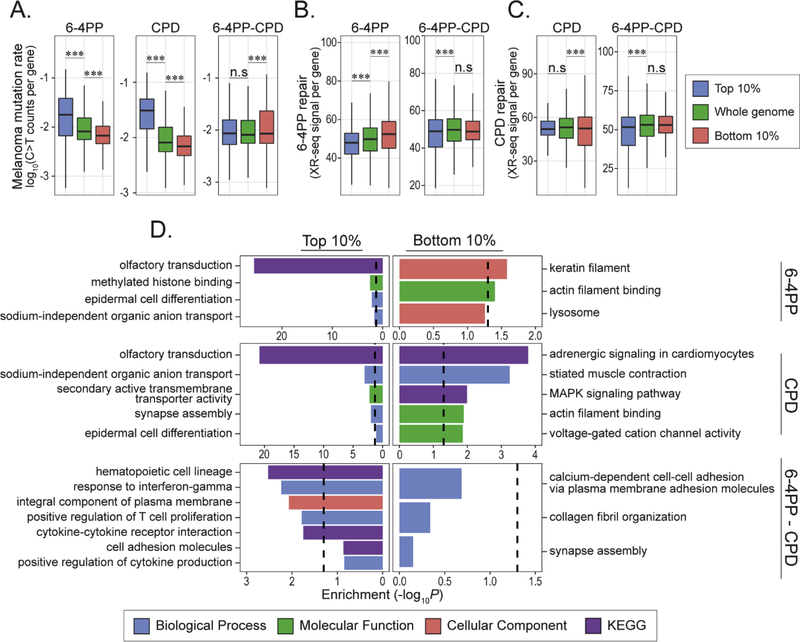

3.4. Contribution of UV susceptibility and repair to mutation frequency in genic regions

As previously described, bot genic regions and enhancers are uniquely susceptible to 6–4PP lesions compared to CPD. When restricting our susceptibility analyses to genic regions we found similar trends to those from whole genome analyses, namely increased susceptibility correlates with increased mutation frequency (Fig. 4A). However, in regions that are preferentially susceptible to 6–4PP formation compared to CPD, there is no significant difference in mutation compared to genome-wide average.

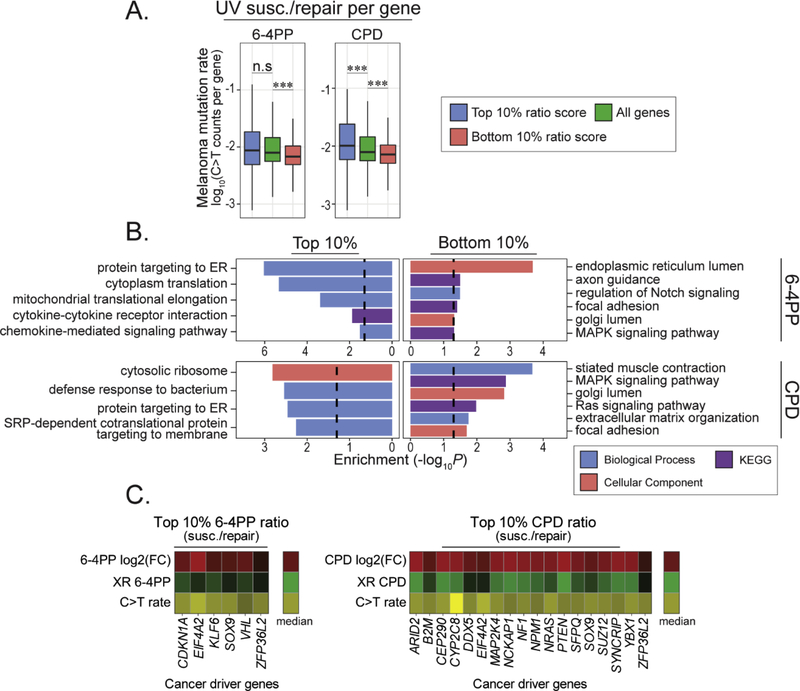

Fig 4: Mutation rate, excision repair and functional enrichment analysis of protein coding genes in differentially UV susceptible regions.

(A) Mutation rates of protein coding genes residing in top and bottom 10% 6–4PP (top, n = 955, bottom, n = 3,924), CPD (top, n = 589; bottom, n = 4,801), and 6–4PP-CPD (top, n = 2,452; bottom, n = 952) compared the median mutation rate of all genes (n = 19,811). (B-C) Cumulative nucleotide excision repair rates of protein coding genes residing within top and bottom 10% genomic 6–4PP and CPD susceptible regions (100kb bin size). (B) 6–4PP excision repair activity in protein coding genes in top and bottom 10% 6–4PP (top, n = 689, bottom, n = 3,585) and 6–4PP-CPD (top, n = 2,012, bottom, n = 840) regions. (C) CPD excision repair activity in protein coding genes in top and bottom 10% CPD (top, n=406, bottom, n = 4,284) and 6–4PP-CPD (top, n = 1,946, bottom, n = 831) regions. Wilcoxon rank sum test: n.s = not significant, ***P < 0.0001. (D) Enrichment analysis of protein coding genes in top and bottom 10% UV susceptible regions was conducted using Enrichr (Chen et al, 2013; Kuleshov et al, 2016). Gene Ontology (biological process, molecular function and cellular component) and KEGG pathways were used. Enrichment values are −log10(P.adjust). Dashed lines denote significance threshold (−log10(0.05)).

Cumulative excision repair activity was also measured for protein coding genes in the top 10% 6–4PP susceptible regions and showed significant decrease in repair compared to all genes, while the top CPD susceptible gene regions did not (Fig. 4B and C). Excision repair in genic regions that are more susceptible to 6–4PP lesion formation than CPD (top 10% 6–4PP - CPD) displayed a small but statistically significant decrease in cumulative repair for both 6–4PP and CPD (Fig. 4B and C). Conversely, genes residing in regions more susceptible to CPD (bottom 10% 6–4PP – CPD) showed no difference in repair activity compared to the whole genome.

To understand the function of genes that are more susceptible to 6–4PPs and CPDs we performed functional enrichment analysis (Fig. 4D, Supplemental Files S2-4). Analysis of protein coding genes in top 10% 6–4PP and CPD regions were both enriched in similar functions involving olfactory transduction pathways and organic anion transport proteins (Fig. 4D). Genes involved in epidermal differentiation and chromatin modifying enzymes such as the histone demethylase protein KDM5A were significantly enriched in top 6–4PP regions. Interestingly, genes in regions more susceptible to 6–4PP (top 10% 6–4PP – CPD) were enriched for various immune-related processes like cytokine-mediated signaling pathways, response to interferon-gamma and genes important for immune cell proliferation and differentiation. Genes enriched in the bottom 10% 6–4PP regions were associated with cytoskeletal filament proteins like actin and keratin, whereas genes enriched in the bottom 10% CPD regions were mainly enriched in functions involving synapse activity such as voltage-gated cation channel activity and muscle contraction but were also enriched for proteins functioning in the MAPK signaling pathway (Fig. 4D).

To further investigate the potential contribution of UV susceptibility and excision repair to mutation frequency, we calculated UV lesion susceptibility to repair ratio (UV ratio) for both 6–4PP and CPD in protein coding regions and compared them with melanoma mutation frequency. As expected, genic regions with relatively lower CPD or 6–4PP susceptibility and higher repair (bottom 10% UV ratio) exhibited lower mutation rates compared to the median mutation rate of all genes in the genome (Fig. 5A). Conversely, genic regions with relatively higher CPD susceptibility and lower repair (top 10% UV ratio) exhibited significantly higher mutation rates. However, genes in the top 6–4PP UV ratio did not have a significant difference compared to all genes.

Fig 5: Mutational and functional enrichment analysis of genes disproportionately influenced by UV susceptibility and/or excision repair activity.

(A) Melanoma mutation rates of protein coding genes with UV susceptibility to repair (susc./repair) ratio scores measured for 6–4PP (left) and CPD (right). (B) Functional enrichment analysis of protein coding genes with top and bottom 10% UV (susc./repair) ratio scores for 6–4PP and CPD. Manually curated Gene Ontology (biological process and cellular component) and KEGG pathways are shown. Enrichment values are the −log10(P.adjust). Dashed lines denote significance threshold (−log10(0.05)). (C) Heatmap showing UV lesion susceptibility, cumulative excision repair and mutation density for melanoma cancer driver genes with top 10% UV ratio scores. Heatmap values for UV susceptibility and repair range from the lower limit (Q1 − 1.57*Interquartile range (IQR)) to the upper limit (Q3 + 1.57*IQR) of each distribution, respectively. Ranges for mutation rate values include the minimum and upper limit (Q3 + 1.57*IQR). Colors depicting the median values for susceptibility, repair and mutation rate are shown.

Genes with the highest (top 10%) 6–4PP and CPD ratios were enriched in functions relating to protein synthesis in the cytoplasm that get targeted to the ER and plasma membrane (Fig. 5B, Supplemental Files S5 and S6). Additionally, genes involved in immune-related pathways were also enriched, such as cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction and defense response to bacterium. In contrast, genes with the lowest (bottom 10%) 6–4PP and CPD ratios were enriched in cellular components involving membrane-bound compartments, such as the ER and golgi (Fig. 5B). Additionally, membrane-associated pathways, such as the MAPK pathway and adhesion proteins were also enriched. Notably, several cancer driver genes are in regions of high UV ratios (Fig. 5C). For example, NRAS, PTEN, NF1, and VHL, are all in regions of high CPD or 6–4PP ratios, suggesting that mutability (susceptibility/repair ratio) is a likely contributor to high mutation frequencies of these genes in melanoma.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that, across the genome, there is a general trend of increased mutation frequency with more UV-induced lesions and less repair. Our analyses also highlight how differential susceptibility and/or repair may contribute to mutation frequency in malignant melanoma. For example, in genic regions, including many cancer driver genes, relatively higher levels of CPD susceptibility are accompanied by repair activity that is comparable to the average, thus increased mutation frequency in these genes may be largely driven by susceptibility. However, genic regions with relatively high 6–4PP and low repair do not exhibit increased mutation frequency in melanoma, suggesting generalized decreased mutagenicity of 6–4PP or negative selection during carcinogenesis. Exceptions for cancer driver genes in these regions are observed, as they have high mutation rates associated with low repair.

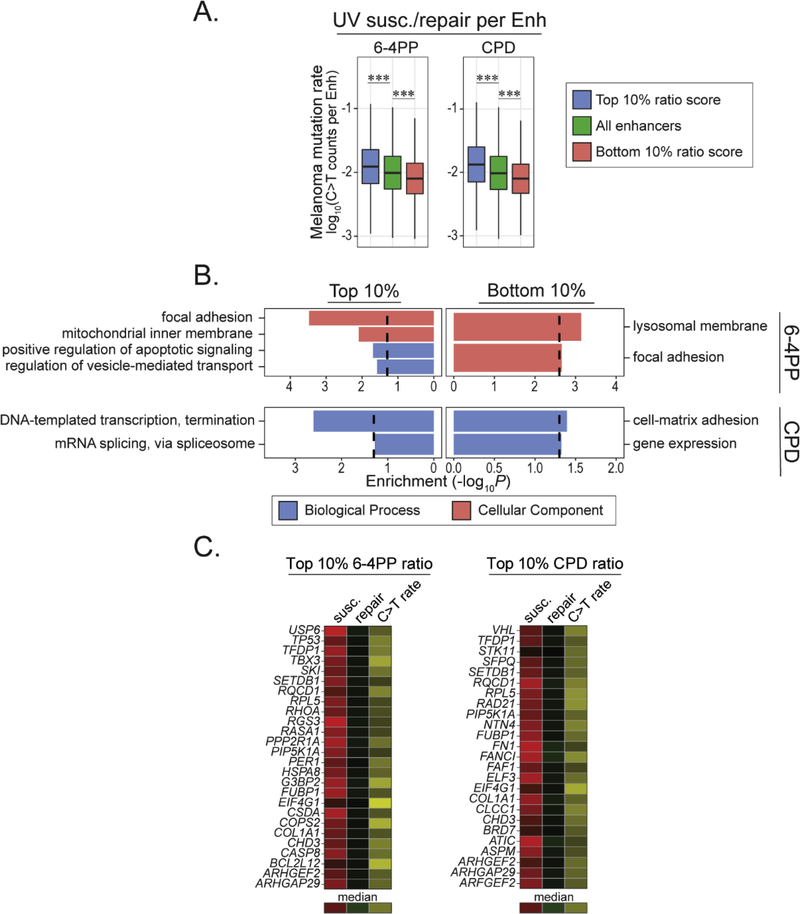

3.5. Contribution of UV susceptibility and repair to mutation frequency in enhancers

We next sought to analyze the mutational burden and excision repair activity within enhancers across the genome and in differentially susceptible regions. We note that the majority of enhancers (~80%) contained C>T mutations, whereas fewer than half of enhancers in the genome displayed detectable levels of excision repair for either 6–4PP or CPD (38% 6–4PP repair and 35% CPD repair; Supp. Fig. 5A and File S7). As expected, mutation rates were lower in enhancers with excision repair compared to enhancers without repair (Supp. Fig. 5B). We also analyzed the percentage of enhancers with mutations and repair in top and bottom 10% UV susceptible regions. The proportion of enhancers with mutations in top and bottom 10% regions (6–4PP, CPD and 6–4PP – CPD) were comparable to the whole genome (Supp. Fig 5C-D). However, the percentage of enhancers with detectable excision repair was markedly lower in top 6–4PP and CPD regions (26% in top 6–4PP and 24% in top CPD). Similar to whole genome trends, mutation rates of enhancers with repair were statistically lower compared to enhancers lacking repair (Supp. Fig. 5E-F). These results reveal that most enhancers in the genome acquire melanoma mutations yet only a small subset are repaired for either 6–4PP or CPD types of damage.

Next, we wanted to determine if there were differences in mutation load and excision repair levels within enhancers residing in regions most susceptible to UV damage. Enhancers with mutations in top and bottom 10% 6–4PP and CPD regions exhibited corresponding changes in mutation frequency (Fig. 6A), similar to the trends found across the whole genome (Fig. 3B) and protein coding genes (Fig. 4A). Repair was inversely associated with susceptibility, as regions with high susceptibility had significant decreases in repair, compared to the median of all enhancers (Fig. 6B and C). Thus, elevated mutation frequency in these enhancers is likely a combination of both increased susceptibility and decreased repair.

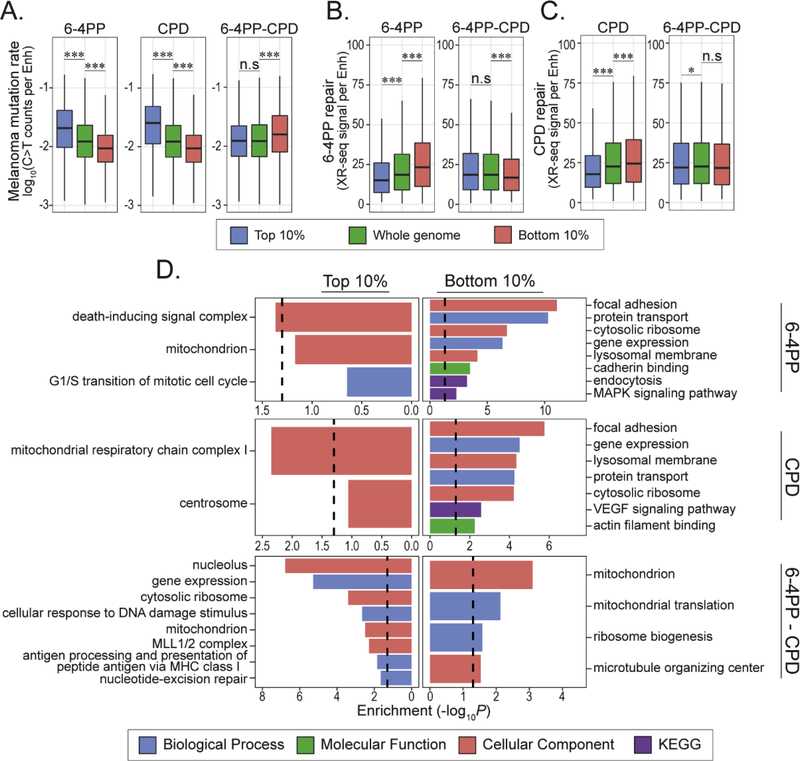

Fig 6: Mutation rates and functional roles of enhancers in differentially UV susceptible regions.

(A) Mutation rates of enhancer elements in top and bottom 10% 6–4PP (top, n = 3,105; bottom, n = 12,210), CPD (top, n = 2,803; bottom, n = 12,684), and 6–4PP-CPD (top, n = 7,014; bottom, n = 4,323) 100kb regions. Predicted enhancer regions for IMR-90 cells were obtained from EnhancerAtlas.org (Gao and Qian, 2019). (B-C) Cumulative nucleotide excision repair rates of enhancers residing within top and bottom 10% genomic 6–4PP and CPD susceptible regions (100kb bins). (B) 6–4PP excision repair activity in enhancer elements in top and bottom 10% 6–4PP (top, n = 920, bottom, n = 7,310) and 6–4PP-CPD (top, n = 3,095, bottom, n = 1,800) regions. (C) CPD excision repair activity in enhancer elements in top and bottom 10% CPD (top, n=627, bottom, n = 6,174) and 6–4PP-CPD (top, n = 2,671, bottom, n = 1,675) regions. Wilcoxon rank sum test: n.s = not significant, ***P < 0.0001. (D) Manually curated enrichment analysis of enhancer-target genes in top and bottom 10% UV susceptible regions. Gene Ontology (biological process, molecular function and cellular component) and KEGG pathways were used. Enrichment values are −log10(P.adjust). Dashed lines denote significance threshold (−log10(0.05)).

However, in enhancers that are uniquely susceptible to 6–4PP versus CPD (top 6–4PP – CPD), there is no significant increase in mutation frequency compared to the median (Fig. 6A).

This is likely due to insignificant differences for 6–4PP repair in these regions compared to the genome median (Fig. 6B). This differs from the situation within genic regions, where repair is significantly decreased in regions with relatively more 6–4PP versus CPD lesions (Fig. 4B). Conversely, similar to genic regions, enhancer regions that are uniquely susceptible to CPD versus 6–4PP (bottom 6–4PP – CPD) have elevated mutation frequency despite having repair activity similar to the genome median (Fig. 6A and C).

We then conduced functional enrichment analysis on the target genes of enhancers in top and bottom 10% UV susceptible regions. The only significantly enriched term in the top 10% 6–4PP regions was death-inducing signal complex (Fig. 6D, Supplemental Files S8-10). In comparison, enhancer-target genes in top 10% CPD regions were enriched for proteins functioning in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Furthermore, enhancer-target genes in regions more susceptible to 6–4PP (top 10% 6–4PP – CPD) were involved in diverse biological processes, such as DNA damage responses, gene expression, and ribosome function. Analysis of enhancer-target genes in regions more susceptible to CPD (bottom 10% 6–4PP – CPD) found enrichments in processes involved in mitochondrial biosynthesis and proteins belonging to the microtubule organizing center.

When assessing mutagenic potential by calculating the ratio of susceptibility to cumulative repair, we found enhancers with the highest ratios for both 6–4PP and CPD had elevated mutation rates, while those with the lowest ratios had decreased mutation rates (Fig. 7A), indicative of both susceptibility and repair contributions to mutation in cancer. Enrichment analysis of enhancers with the highest 6–4PP ratios were found to interact with genes involved in cell adhesion, transport, apoptosis and proteins that localize to the mitochondria (Fig. 7B, Supplemental Files S11 and S12). Furthermore, enhancers with the highest CPD ratios interact with genes involved in transcription and splicing while enhancers with the lowest ratios for 6–4PP and CPD had interactions with genes involving lysosome and cell adhesion function, respectively.

Fig 7: Mutation rate and functional enrichment analysis of genes and enhancers with top and bottom UV susceptibility/repair scores.

(A) Mutation rate and functional enrichment analysis of enhancers with top and bottom 10% UV susceptibility/excision repair ratio scores. UV ratio scores were measured from 6–4PP (left) and CPD (right) lesion abundance and their respective repair levels. (B) Enrichment analysis of enhancer-target genes with top and bottom 10% UV ratio scores. Manually curated Gene Ontology annotations for biological process and cellular component are shown. Enrichment values are −log10(P.adjust). Dashed lines denote significance threshold (−log10(0.05)). (C) Heatmap showing UV lesion susceptibility, cumulative excision repair and mutation density for melanoma cancer driver genes that interact with enhancers with top 10% UV ratio scores. The mean values for susceptibility, repair and mutation rate were used for multiple enhancers targeting the same gene (Supplemental File S13). Heatmap values for UV susceptibility and repair range from the lower limit (Q1 − 1.57*IQR) to the upper limit (Q3 + 1.57*IQR) of each distribution, respectively. Ranges for mutation rate values include the minimum and upper limit (Q3 + 1.57*IQR). Colors depicting the median values for susceptibility, repair and mutation rate are shown.

Interestingly, several cancer driver genes were identified as targets for enhancers in regions with high UV ratios. For example, TP53 and VHL, were associated with enhancers in top 6–4PP and CPD ratio regions, respectively.

Collectively, these enhancer analyses indicate that mutation frequency in melanoma is largely contributed by both increases in susceptibility and lack of repair. As with the genic regions, enhancers that are uniquely susceptible to 6–4PP than CPD have no significant increase in mutation frequency. However, unlike genic regions, this may be largely due to relatively average repair levels, while genic regions are repaired less than average. Again, exceptions include enhancers of several cancer driver genes with top 6–4PP and CPD ratio scores, as they largely exhibit increased susceptibility and decreased repair, both of which likely contributing to elevated mutation frequency in melanoma.

4. Discussion

Results from this study show that genome-wide distribution of 6–4PP lesions coincide with CPD distribution and were most abundant in heterochromatin near the nuclear periphery. As previously described, several genetic and epigenetic factors likely regulate differential susceptibility in these regions (García-Nieto et al, 2017). For example, it is notable that TpT and TpC, which favor UV lesion formation (Douki and Cadet, 2001), are enriched in heterochromatin and transcriptionally repressed states. It is also possible that specific structural features within these highly condensed states can more readily facilitate the formation of UV lesions. For example, it has been shown that the conformation of DNA in complex with chromosomal proteins like histone octamers can modulate UV-induced lesion formation (Gale et al, 1987; Mitchell et al, 1990b). Another possibility likely involves spatial organization of chromatin in the nucleus. Indeed, the “bodyguard hypothesis” first proposed by Hsu in 1975 suggests that heterochromatin located at the nuclear periphery protects gene-rich euchromatin located in the interior (Hsu, 1975).

Nevertheless, comparing the relative differences between 6–4PP and CPD abundance levels, we identified distinct chromatin regions demarcated by bivalent and Polycomb repressed epigenetic features that are more susceptible to 6–4PP formation compared to CPDs. These regions were also enriched for enhancers and genic features, including promoters, 5’UTRs and exons. In addition, we identified enrichment of several repetitive elements, such as SINEs and LTR retrotransposons, which localize within or near euchromatic and heterochromatic regions, respectively (Estécio et al, 2012; Solovei et al, 2016). Notably, in bivalent and Polycomb repressed regions there is a significant difference in the abundance of specific di-pyrimidines, namely TpT and TpC that form CPDs and 6–4PPs at variable frequencies. Thus, DNA content is a likely contributor to susceptibility in these regions. This highlights the importance of genetic diversity throughout the genome as a critical determinant for UV-induced damage susceptibility and subsequent mutagenesis.

Analysis of susceptibility, repair and mutation frequency across the genome revealed both positive susceptibility and negative repair correlations with melanoma mutation frequency. As expected, these results demonstrate that mutagenic potential is contributed by both UV susceptibility and repair. However, when examining specific regions of the genome, such as those that contain protein coding genes, significant differences in mutagenic potential were identified. For example, disproportionate differences between susceptibility and repair in genic regions suggest that elevated susceptibility may largely influence mutation rates. It should be noted that we do not have the sequencing depth to extend these observations to single-base resolution, thus our observations are generalized to larger genomic domains.

Interestingly, we identified several oncogenes and tumor suppressors with higher mutagenic potential (susceptibility/repair ratio), such as NRAS, PTEN, NF1, ARID2, and VHL. In addition, enhancers of several tumor suppressors were also found to have higher mutagenic potential, such as TP53, NF1, and VHL. These results reveal that many cancer driver genes are, in fact, predisposed to mutation by being in genomic regions with relatively high susceptibility and low repair.

Notably, we found that the majority of genic and enhancer regions that are more uniquely susceptible to 6–4PP than CPDs do not have corresponding increases in melanoma mutation frequency. However, it should be noted that the method we used to rank normalize each dataset does not account for differences in the total abundance of each UV-induced lesion, and that CPDs are generally more abundant that 6–4PPs (Mitchell et al, 1990a; Douki and Cadet, 2001). Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the possibility of negative selection for these regions. In recent years, several studies have identified genes under significant negative selection in various cancers (Van den Eynden et al, 2016). For example, enhancers of genes involved in essential cellular components, such as ribosome, nucleolus, and mitochondrion, were identified as more susceptible to 6–4PPs than CPDs. 6–4PP damage has also been observed to be potent trigger of apoptosis in mammalian cells, whereas CPD primarily induce cell cycle arrest (Lo et al, 2005; Mitchell and Nairn, 1989). Apoptosis triggered by 6–4PP damage could then contribute to negative selection in a tumor population. Furthermore, apoptosis also plays an important role in skin aging (Haake et al, 1998), and may suggest an additional role for 6–4PP in photoaging.

In addition, immune-related signaling pathways and structural components localized to the cell periphery (e.g. “cytokine-mediated signaling pathway” and “integral component of plasma membrane”) were enriched in regions more susceptible to 6–4PP than CPD and have been identified as targets of negative selection in melanoma (Pyatnitskiy et al, 2016; Zapata et al, 2018). In particular, mutation may lead to the development of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) neo-antigens, which has been proposed to facilitate immune evasion of cancer cells from the host immune surveillance system (Pyatnitskiy et al, 2015).

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study is the first to examine differential susceptibilities and repair for the most abundant and mutagenic UV-induced lesions and primary contributors to mutation in melanoma. Higher resolution studies with more sequencing depth will surely extend these initial observations and provide more information on UV-induced mutagenesis that contributes to carcinogenesis. Additional research may also find interesting parallels between mutagenic potential associated with UV-induced damage and that of other carcinogens, potentially revealing evolutionarily-conserved process for tolerance of environmental genotoxins.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental File S1. Melanoma Cancer Driver Genes

Supplemental File S2. Enrichment of 64PP Genes

Supplemental File S3. Enrichment of CPD Genes

Supplemental File S4. Enrichment of 64PP-CPD Genes

Supplemental File S5. Enrichment of 64PP Ratio Genes

Supplemental File S6. Enrichment of CPD Ratio Genes

Supplemental File S7. Enhancer mutations and Excision Repair

Supplemental File S8. Enrichment of Enhancer-Target 64PP Genes

Supplemental File S9. Enrichment of Enhancer-Target CPD Genes

Supplemental File S10. Enrichment of Enhancer-Target 64PP-CPD Genes

Supplemental File S11. Enrichment of Enhancer-Target 64PP Ratio Genes

Supplemental File S12. Enrichment of Enhancer-Target CPD Ratio Genes

Supplemental File S13. Enhancer-Cancer Driver Genes with Top UV Ratios

Highlights.

Across the genome, 6–4PP and CPD lesions have broadly similar distributions

Chromatin differentially susceptible to 6–4PPs are bivalent and Polycomb-repressed enhancers and genic features

Genes and enhancers more susceptible to 6–4PPs than CPD are associated with cell viability and immune-related pathways

Both 6–4PP and CPD lesions correlate with C>T mutation rates across the genome

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Aziz Sancar for providing us with CPD and 6-4PP photolyases used for DNA repair. BSP is supported by the National Institute of Health grant T32 GM007276 and is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Gilliam Fellow. AJM received funding support from NIH NCI awards R21CA178529 and R21CA171050. We thank all members of the Morrison lab for helpful suggestions

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adar S, Hu J, Lieb JD, Sancar A. Genome-wide kinetics of DNA excision repair in relation to chromatin state and mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(15):E2124–E2133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603388113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbani R, Akdemir KC, Aksoy BA, et al. Genomic Classification of Cutaneous Melanoma. Cell. 2015;161(7):1681–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500(7463):415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey MH, Tokheim C, Porta-Pardo E, et al. Comprehensive Characterization of Cancer Driver Genes and Mutations. Cell. 2018;173(2):371–385.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balajee AS, Bohr VA. Genomic heterogeneity of nucleotide excision repair. Gene. 2000;250(1–2):15–30. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00172-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley TM, Erickson S, Allison DB. Rank-based inverse normal transformations are increasingly used, but are they merited? Behav Genet. 2009;39(5):580–595. doi: 10.1007/s10519-009-9281-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolzer A, Kreth G, Solovei I, et al. Three-dimensional maps of all chromosomes in human male fibroblast nuclei and prometaphase rosettes. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(5):0826–0842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brash DE, Rudolph JA, Simon JA, et al. A role for sunlight in skin cancer: UV-induced p53 mutations in squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(22):10124–10128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, et al. Enrichr: Interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14(4):128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gruijl FR. Skin cancer and solar UV radiation. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(14):2003–2009. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00283-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douki T, Cadet J. Individual determination of the yield of the main UV-induced dimeric pyrimidine photoproducts in DNA suggests a high mutagenicity of CC photolesions. Biochemistry. 2001;40(8):2495–2501. doi: 10.1021/bi0022543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham I, Kundaje A, Aldred SF, et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489(7414):57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estécio MRH, Gallegos J, Dekmezian M, Lu Y, Liang S, Issa JPJ. SINE retrotransposons cause epigenetic reprogramming of adjacent gene promoters. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10(10):1332–1342. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale JM, Nissen KA, Smerdon MJ. UV-induced formation of pyrimidine dimers in nucleosome core DNA is strongly modulated with a period of 10.3 bases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(19):6644–6658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T, Qian J. EAGLE: An algorithm that utilizes a small number of genomic features to predict tissue/cell type-specific enhancer-gene interactions. Ioshikhes I, ed. PLOS Comput Biol. 2019;15(10):e1007436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T, Qian J. EnhancerAtlas 2.0: An updated resource with enhancer annotation in 586 tissue/cell types across nine species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D58–D64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Nieto PE, Schwartz EK, King DA, et al. Carcinogen susceptibility is regulated by genome architecture and predicts cancer mutagenesis. EMBO J. 2017;36(19):2829–2843. doi: 10.15252/embj.201796717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Perez A, Perez-Llamas C, Deu-Pons J, et al. IntOGen-mutations identifies cancer drivers across tumor types. Nat Methods. 2013;10(11):1081–1084. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guelen L, Pagie L, Brasset E, et al. Domain organization of human chromosomes revealed by mapping of nuclear lamina interactions. Nature. 2008;453(7197):948–951. doi: 10.1038/nature06947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haake AR, Roublevskaia I, Cooklis M. Apoptosis: A Role in Skin Aging?; 1998. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.1998.8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Harikumar A, Meshorer E. Chromatin remodeling and bivalent histone modifications in embryonic stem cells. EMBO Rep. 2015;16(12):1609–1619. doi: 10.15252/embr.201541011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward NK, Wilmott JS, Waddell N, et al. Whole-genome landscapes of major melanoma subtypes. Nature. 2017;545(7653):175–180. doi: 10.1038/nature22071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnisz D, Abraham BJ, Lee TI, et al. XSuper-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell. 2013;155(4):934. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodis E, Watson IR, Kryukov G V., et al. A Landscape of Driver Mutations in Melanoma. Cell. 2012;150(2):251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsfall MJ, Borden A, Lawrence CW. Mutagenic properties of the T-C cyclobutane dimer. J Bacteriol. 1997;179(9):2835–2839. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2835-2839.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsfall MJ, Lawrence CW. Accuracy of replication past the T-C (6–4) adduct. J Mol Biol. 1994;235(2):465–471. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu F, Kent JW, Clawson H, Kuhn RM, Diekhans M, Haussier D. The UCSC known genes. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(9):1036–1046. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu TC. A possible function of constitutive heterochromatin: the bodyguard hypothesis. Genetics. 1975;79 Suppl:137–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Adar S, Selby CP, Lieb JD, Sancar A. Genome-wide analysis of human global and transcription-coupled excision repair of UV damage at single-nucleotide resolution. Genes Dev. 2015;29(9):948–960. doi: 10.1101/gad.261271.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Adebali O, Adar S, Sancar A. Dynamic maps of UV damage formation and repair for the human genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(26):6758–6763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706522114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Zhang X. DbSUPER: A database of Super-enhancers in mouse and human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D164–D171. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J-K, Patel D, Choi B-S. CONTRASTING STRUCTURAL IMPACTS INDUCED BY cis-syn CYCLOBUTANE DIMER AND (6–4) ADDUCT IN DNA DUPLEX DECAMERS: IMPLICATION IN MUTAGENESIS AND REPAIR ACTIVITY. Photochem Photobiol. 1995;62(1):44–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1995.tb05236.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W90–W97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo HL, Nakajima S, Ma L, et al. Differential biologic effects of CPD and 6–4PP UV-induced DNA damage on the induction of apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund E, Oldenburg AR, Collas P. Enriched domain detector: A program for detection of wide genomic enrichment domains robust against local variations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(11):e92–e92. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao P, Wyrick JJ, Roberts SA, Smerdon MJ. UV-Induced DNA Damage and Mutagenesis in Chromatin. Photochem Photobiol. 2017;93(1):216–228. doi: 10.1111/php.12646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteijn JA, Lans H, Vermeulen W, Hoeijmakers JHJ. Understanding nucleotide excision repair and its roles in cancer and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(7):465–481. doi: 10.1038/nrm3822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DL, Allison JP, Nairn RS. Immunoprecipitation of Pyrimidine(6–4)pyrimidone Photoproducts and Cyclobutane Pyrimidine Dimers in uv-Irradiated DNA. Radiat Res. 1990(a);123(3):299. doi: 10.2307/3577736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DL, Nairn RS. The biology of the (6–4) photoproduct. Photochem Photobiol. 1989;49(6):805–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1989.tb05578.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DL, Nguyen TD, Cleaver JE. Nonrandom induction of pyrimidine-pyrimidone (6–4) photoproducts in ultraviolet-irradiated human chromatin. J Biol Chem. 1990(b);265(10):5353–5356. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2318816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DM, Jaber-Hijazi F, Cole JJ, et al. Mapping H4K20me3 onto the chromatin landscape of senescent cells indicates a function in control of cell senescence and tumor suppression through preservation of genetic and epigenetic stability. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):1–20. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1017-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata H, Goto S, Fujibuchi W, Kanehisa M. Computation with the KEGG Pathway Database. Vol 47. Elsevier; 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0303-2647(98)00017-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen J, Liyakat Ali TM, Collas P. Computational 3D genome modeling using Chrom3D. Nat Protoc. 2018;13(5):1137–1152. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2018.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen J, Sekelja M, Oldenburg AR, et al. Chrom3D: Three-dimensional genome modeling from Hi-C and nuclear lamin-genome contacts. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1146-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polak P, Karlic R, Koren A, et al. Cell-of-origin chromatin organization shapes the mutational landscape of cancer. Nature. 2015;518(7539):360–364. doi: 10.1038/nature14221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyatnitskiy M, Karpov D, Poverennaya E, Lisitsa A, Moshkovskii S. Bringing Down Cancer Aircraft: Searching for Essential Hypomutated Proteins in Skin Melanoma. Chammas R, ed. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142819. doi: 10.1371/journalpone.0142819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SSPP, Huntley MH, Durand NC, et al. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell. 2014;159(7):1665–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravanat JL, Douki T, Cadet J. Direct and indirect effects of UV radiation on DNA and its components. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2001;63(1–3):88–102. doi: 10.1016/S1011-1344(01)00206-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium, Kundaje A, Meuleman W, et al. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015;518(7539):317–330. doi: 10.1038/nature14248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadaie M, Salama R, Carroll T, et al. Redistribution of the Lamin B1 genomic binding profile affects rearrangement of heterochromatic doma.pdf. Genes Dev. 2013;27(1):1800–1808. doi: 10.1101/gad.217281.113.Freely [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster-Böckler B, Lehner B. Chromatin organization is a major influence on regional mutation rates in human cancer cells. Nature. 2012;488(7412):504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature11273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby CP, Sancar A. A cryptochrome/photolyase class of enzymes with single-stranded DNA-specific photolyase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(47):17696–17700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607993103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solovei I, Thanisch K, Feodorova Y. How to rule the nucleus: divide et impera. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2016;40:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Eynden J, Basu S, Larsson E. Somatic Mutation Patterns in Hemizygous Genomic Regions Unveil Purifying Selection during Tumor Evolution. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(12):1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You YH, Lee DH, Yoon JH, Nakajima S, Yasui A, Pfeifer GP. Cyclobutane Pyrimidine Dimers Are Responsible for the Vast Majority of Mutations Induced by UVB Irradiation in Mammalian Cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(48):44688–44694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107696200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapata L, Pich O, Serrano L, Kondrashov FA, Ossowski S, Schaefer MH. Negative selection in tumor genome evolution acts on essential cellular functions and the immunopeptidome. Genome Biol. 2018;19(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1434-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental File S1. Melanoma Cancer Driver Genes

Supplemental File S2. Enrichment of 64PP Genes

Supplemental File S3. Enrichment of CPD Genes

Supplemental File S4. Enrichment of 64PP-CPD Genes

Supplemental File S5. Enrichment of 64PP Ratio Genes

Supplemental File S6. Enrichment of CPD Ratio Genes

Supplemental File S7. Enhancer mutations and Excision Repair

Supplemental File S8. Enrichment of Enhancer-Target 64PP Genes

Supplemental File S9. Enrichment of Enhancer-Target CPD Genes

Supplemental File S10. Enrichment of Enhancer-Target 64PP-CPD Genes

Supplemental File S11. Enrichment of Enhancer-Target 64PP Ratio Genes

Supplemental File S12. Enrichment of Enhancer-Target CPD Ratio Genes

Supplemental File S13. Enhancer-Cancer Driver Genes with Top UV Ratios

Data Availability Statement

Raw sequencing and signal track files generated in this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession number GSE157070). All code used in this study is available at our github repository (https://github.com/MorrisonLabSU).