Abstract

Background:

Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) is common in low-income countries such as Malawi and is associated with high mortality in young children.

Objective:

To improve recognition and management of SAM in a tertiary hospital in Malawi.

Methods:

The impact of multifaceted quality improvement interventions in multiple process measures pertaining to identification and management of children with SAM using a before-after design was assessed. Interventions included focused training for clinical staff, reporting process measures to clinical staff, and mobile phone-based group messaging for enhanced communication. This initiative focused on children aged 6–36 months admitted to Kamuzu Central Hospital in Malawi from 18 September 2019 to 17 March 2020. Before-after comparisons were made with baseline data from the year prior, and process measures within this intervention period that included three plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles were compared.

Results:

During the intervention period, 418 children had SAM and in-hospital mortality was 10.8%, which was not significantly different than the baseline period. Compared with the baseline period, there was significant improvement in the documentation of full anthropometrics on admission, blood glucose test within 24 hours of admission and HIV testing results by discharge. During the intervention period, amidst increasing patient census with each PDSA cycle, three process measures were maintained (documentation of full anthropometrics, determination of nutrition status and HIV testing results) and there was significant improvement in blood glucose documentation.

Conclusions:

Significant improvement in key quality measures represents early progress towards the larger goal of improving patient outcome, most notably mortality, in children admitted with SAM.

Keywords: Severe acute malnutrition, quality improvement, Malawi

Introduction

Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) affects over 14 million children under the age of 5 years worldwide [1]. The United Nations estimates that poor nutrition causes 45% of deaths in this age group and that food insecurity continues to worsen in sub-Saharan Africa [2]. The COVID-19 pandemic is predicted to further worsen food insecurity, malnutrition, and consequently under-five child mortality in low- and middle-income countries [3,4].

For children aged 6–59 months, SAM is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the presence of any bilateral pitting oedema, a mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) of <11.5 cm, or a weight-for-length Z-score <-3 [5]. The majority of SAM cases are uncomplicated and can be effectively managed in a community-based setting [6]. Children with SAM and poor appetite, severe oedema (3+, defined as bilateral feet, hands and peri-orbital oedema), marasmic kwashiorkor, infections, or presenting with one or more Integrated Management of Childhood Illness danger signs are classified as complicated SAM and should be stabilised as inpatients [5]. The management of complicated SAM in the inpatient setting is based upon well defined guidelines published by WHO [5,6]. These guidelines are widely adopted at the national level in many countries with a high burden of SAM, including in Malawi [7]. In addition, Malawi guidelines for the management of acute malnutrition emphasise the importance of regular, directed quality improvement activities at the facility level to optimise care of this high-mortality population [7].

This project developed from an ongoing multi-institutional partnership between Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH, a tertiary government referral hospital in Lilongwe, Malawi) and the Pediatric Alliance for Child Health Improvement in Malawi at KCH and Environs (PACHIMAKE; a consortium of four US-based paediatric hospitals) aimed at improving the care of acutely ill children through implementation of high quality and sustainable clinical, educational, and research initiatives [8]. A retrospective chart review of children who died while hospitalised at KCH in 2015 detected large gaps in the timely recognition of SAM [9]. Additionally, using data from a separate prospective paediatric inpatient care database, risk factors for mortality and management of children with complicated SAM at KCH have been reported recently [10]. Of all children aged 6–36 months admitted to the paediatric inpatient ward at KCH from September 2018 to the end of September 2019, 9.7% had SAM and the in-hospital mortality of those with SAM was 10.1%. As a result of these data, the KCH Paediatric Department identified SAM as a high-priority focus and assembled a team of clinicians, nurses, nutritionists and nutrition assistants to collaboratively develop and implement a quality-improvement initiative to improve care and outcome in this vulnerable population.

The aim of this quality improvement initiative was to increase the recognition, and address gaps in the management of SAM by healthcare providers at Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH) so that mortality in this population would ultimately decrease.

Methods

This study was a quality improvement comparison with a before-after design and was approved by the institutional ethical review boards of the Malawi National Health Sciences Research Committee (protocol number 17/07/1870) and the University of North Carolina (study number 17–1942). As this study includes only information that is routinely collected for patient care and part of the standard medical record, the ethical review boards approved a waiver of informed consent.

Setting and study population

This intervention took place at Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH), a tertiary referral centre in Lilongwe, Malawi, that serves a population of about 7 million people. Each year, the paediatric ward admits up to 25,000 patients to its 299-bed facility. The bulk of the clinical care is provided by nursing staff and a permanent staff of clinical officers (COs) and rotating medical interns supervised by at least one paediatric consultant physician on call at all times. COs have completed a diploma-level training programme, with some having undergone further training with a Bachelor of Paediatrics and Child Health. Medical interns complete a 14-week rotation in the department. There is a permanent clinical staff member assigned to oversee the paediatric intake area (Under 5 unit), and another to oversee the Nutritional Rehabilitation Unit (NRU) and the Emergency Zone (EZ, an acute care ward). The department is often significantly understaffed, and health workers who are present have often received little formal training in the identification and management of SAM.

Since September 2017, PACHIMAKE and KCH have maintained a comprehensive database describing inpatients ages two weeks to 60 months who present acutely to the paediatric ward for care. The creation and implementation of the database and a complete description of the variables collected has been described previously [11].

Local standards of care for SAM

The cascade of care for the inpatient management of SAM at KCH is based on the Malawian Ministry of Health Guidelines [7] which are adapted from the WHO guidelines [5,6]. Initial steps occur in the Under 5 unit, where patients either present directly from the community or as referrals from other facilities. Measurement of weight, height, and MUAC, and assessment for oedema occurs in the Under 5 unit. These anthropometric measurements determine a child’s nutritional status and are carried out by nutritionist interns who often lack mentorship and oversight. The clinical team must then interpret the anthropometrics to identify children with SAM, document the diagnosis, and initiate appropriate management. For those with SAM, assessment must also include determination of severity of illness. A small subset of patients with SAM in the Under-5 unit have uncomplicated SAM (defined above) and are referred for immediate outpatient management. The majority have complicated SAM and are admitted to KCH for further management and stabilisation. These patients should be cohorted in the NRU if they are relatively stable, or in the EZ if they have more severe illness.

Intervention

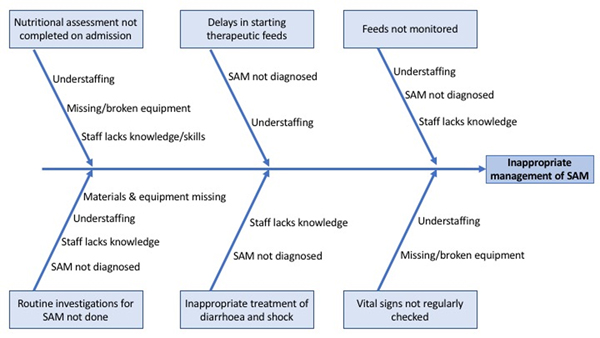

The study had two phases. Phase One consisted of baseline data collection for 6 months from September 2018 until March 2019, the results of which have already been published [10]. Phase Two entailed several plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles for intervention implementation, with continuous data collection for 6 months from September 2019 until March 2020. In August 2019, a multi-disciplinary team was assembled to review existing KCH data about the care of SAM patients, identify gaps in care and develop strategies to improve these deficiencies. The team consisted of the nurse matrons in charge of U5 and the NRU, the Deputy Head of the Paediatric Department, the NRU-assigned CO and the NRU staff. Identification of gaps in care was driven by baseline data from Phase One. Certain important aspects of SAM management such as assessment for hypothermia were not emphasised in Phase Two if gaps had not been identified in Phase One [10]. Table 1 defines the roles of the various staff involved in this quality improvement project. Figure 1 describes contributory factors. Five specific gaps were prioritised for focused improvement efforts (Table 2). Table 2 describes the project’s aims using the SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, time-bound) mnemonic.

Table 1.

Position and role of staff involved in the quality improvement initiative.

| Position | Role |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Nurses including those overseeing care of children in the Under-5 unit and in the NRU | • Overall leaders for implementation of activities in different units • Ensure required equipment is available • Coordinate quality improvement activities with other nurses throughout the paediatric ward • Educate and mentor other nurses in care of patients with SAM • Participate in quality improvement meetings to assess progress and direct future activities |

| Nutritionist Manager | • Supervise nutrition interns and other staff providing nutrition services • Oversee administration of therapeutic feeds • Participate in quality improvement meetings to assess progress and direct future activities |

| Nutritionist Interns | • Conduct nutrition assessment of all patients • Link patients with SAM into early steps of SAM care pathway, including obtaining labs and initiation of therapeutic feeds • Provide two daily updates to NRU team on WhatsApp group • Link patients to HIV testing and counselling services • Participate in quality improvement meetings to assess progress and direct future activities |

| Clinicians: Deputy Head of the Paediatric Department, NRU-assigned clinical officer, temporary foreign paediatricians | • Co-lead with nurses the implementation of activities at different units • Coordinate quality improvement activities with other clinicians throughout the paediatric ward • Educate and mentor other clinicians in the care of patients with SAM • Lead quality improvement meetings |

NRU: nutritional rehabilitation unit; SAM: severe acute malnutrition

Figure 1.

Fishbone diagram illustrating challenges in management of patients with SAM.

Table 2.

Specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, time-bound (SMART) aims of identified prioritised gaps.

| By the first quarter of 2020 (Jan to March) for children aged 6–36 months admitted to KCH: | |

|

| |

| Full anthropometrics documented for all admissions | >97% |

| For those with SAM, SAM status is clearly documented | >50% |

| For those with SAM, blood glucose documented within 24 hrs of admission | >50% |

| For those with SAM, HIV status documented by discharge | >90% |

| For those with severe oedema, urine dipstick results documented within 48 hours of admission | >50% |

Phase Two, Cycle A (18 September to 24 November 2019):

Full PDSA cycle barriers and interventions are shown in Table 3. In brief, the first quality-improvement cycle intervention consisted of the following key components: (a) the Paediatric Department nurses and clinicians were given an overview of the baseline data and introduced to this quality improvement initiative during the daily morning handover; (b) in-person training was given for all ward nurses and clinicians who care for SAM patients, focused on how to conduct nutritional assessments, identify patients with SAM and manage their inpatient care. This training was conducted by the quality improvement team, was 2 days in length, and was based on Malawi guidelines for management of SAM [7]; and (c) to address the gap in HIV identification, a meeting was held with the HIV Testing and Counselling (HTC) team to discuss the baseline data demonstrating deficiencies in coverage of HIV testing of children with SAM. Patient flow factors inhibiting HIV testing were identified of which the HTC team was previously unaware.

Table 3.

Plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle barriers and associated interventions during the quality improvement initiative.

| Period | Barrier | Intervention |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Cycle A 18 Sept to 24 Nov 2019 |

SAM not diagnosed | • A nutritionist manager was hired and made responsible for overseeing nutritional assessment of all admissions and coordinating SAM care • Task-shifted nutritional assessments from data clerks to nutritionist interns (continued in Cycle B) |

| Understaffing/absenteeism | • Nutritionist manager tasked with oversight of NRU staff • Monthly NRU team schedule posted on WhatsApp group |

|

| Missing/broken equipment | • MUAC tape, scale, length board, and glucometer procured | |

| Staff lacks knowledge of SAM management | • 2-day guideline-based training for clinicians and nurses in identifying and managing complicated SAM • Permanent staff nurses and clinicians given overview of baseline data and introduction to these interventions • Charts created for patient care areas that detail the guidelines for inpatient management of SAM |

|

| Cycle B 25 Nov to 15 Jan 2020 |

Although documentation of SAM improved, clinical team not documenting the diagnosis nor appropriately managing those with SAM Power dynamics prevent NRU team from informing/reminding clinicians when SAM is identified or gaps in care occur | • NRU team encouraged to continue engaging clinicians • NRU team and nurses given permission to bypass clinicians to implement SAM management • Initiation of NRU team WhatsApp group with twice-daily updates from the team, including real-time updates on stockouts, faulty equipment, number of patients screened and found to have SAM, and handover of tasks to be followed up by the oncoming shift • Nutritionist manager added to ward clinical WhatsApp group to facilitate NRU consults |

| Cycle C 16 Jan to 17 March 2020 |

With increasing patient census, resources strained Ongoing disconnect between clinicians and NRU team to implement coordinated SAM management, especially in the EZ |

• Implementation of a register of SAM patients in the EZ that allows for central tracking of patients and detection of gaps in management of individual patients • Continued reminders to the staff of the initiative and the importance of SAM documentation and guidelines during morning meetings. • Nutritionist manager tasked with orientation of new NRU staff and clinicians to initiative and guidelines • Began staffing speciality follow-up clinics (cardiology, endocrine) |

| Future Interventions | High rate of post-discharge mortality and re-admission of SAM patients | • Home follow-up of recently discharged patients |

| Poor clinician engagement | • Hire clinician dedicated to management of SAM and providing consistent training and mentorship to department clinicians | |

| Vitals signs not regularly assessed and missed doses of medications | • Dedicated nursing staff for management of SAM | |

EZ: Emergency Zone, an acute care ward; MUAC: mid-upper-arm circumference; NGO: non-government organisation; NRU: nutritional rehabilitation unit; SAM: severe acute malnutrition.

Phase Two, Cycle B (25 November 2019 to 15 January 2020).

During this cycle, the team noted improvement in the assessment of children for malnutrition but recognised a persistent gap in the communication between the NRU team and the clinicians, which led to under-documentation of SAM and subsequently poor adherence to management protocols. Inherent to this poor communication was the power differential between the clinical staff and the nutritionist interns. Strategies to overcome this were identified by the two groups, including direct communication with the nursing team, bypassing the clinician to initiate feeds, and discussing with the Deputy Head of Department when issues arose with specific clinicians.

As a response to the above conversation, a handover process was created for the nutritionist interns, and twice-daily updates were initiated on a text messaging group using the WhatsApp mobile phone application. These updates include the number of children assessed, the number with SAM, whether patients received the appropriate initial tests and were started on feeds, and group discussions to troubleshoot general issues that arose.

Phase Two, Cycle C (16 January to 17 March 2020).

This cycle occurred during the peak of the malnutrition season, and the census was high. The team struggled with ongoing communication problems between the clinical staff and the nutritionist interns. A register of patients admitted with SAM was created to track them within the different departments and to help identify gaps in management.

Throughout this project, the Paediatric Department was updated monthly on key metrics during staff meetings and via a departmental WhatsApp group.

Measurements

Table 4 describes the measures for this improvement project. While the outcome and process measures were quantitatively measured, the balance measures were gathered through feedback from the team throughout the course of the project.

Table 4.

Quality improvement measures. Outcome measures are patient-centred experiences. Process measures describe steps in a system performing as planned. Balance measures are unintended consequences in the system.

| Measure | Measure Type |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Proportion lost to follow-up or with in-patient mortality | Outcome |

| Proportion with full anthropometrics | Process |

| Proportion with SAM status documented | Process |

| Proportion with blood glucose documented within 24 hours | Process |

| Proportion with HIV status documented by discharge | Process |

| Proportion with severe oedema with urine dipstick documented within 48 hours | Process |

| Increased resource usagea | Balance |

| • Staffing for nutrition assessments and HIV testing | |

| • Glucose testing and urine dipstick supplies | |

Qualitative measure through feedback from team.

Outcome measures are patient-centred experiences. Process measures describe steps in a system performing as planned. Balance measures are unintended consequences in the system.

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed using Stata version 16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Clinical outcome and target quality gaps were summarised using descriptive statistics. Proportions were compared between the baseline and intervention time periods, and between the different PDSA cycles, using the χ2 test. For all comparisons, statistical significance was achieved with p<0.05.

Results

Data on 418 children with SAM admitted to KCH during the intervention period were included in the analysis. Of these 418 children, 54.1% were male, 65.3% were aged 6–20 months and 34.7% were aged 21–36 months (data not shown). Although both periods included the same months (September to the following March) over 2 consecutive years, the intervention time period involved 21% more total admissions (4652 vs 3665) and 8% more SAM cases (418 vs 385) compared with the baseline period (Table 5). However, proportions of outcome for total admissions and SAM admissions were not significantly different between the two time periods. Specifically, no statistically significant difference was seen in mortality between the baseline and intervention periods.

Table 5.

Hospital outcome in all patients and patients with SAM during the baseline (18 September 2018 and 17 March 2019) and intervention periods (18 September 2019 and 17 March 2020).

| Baseline | Intervention | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Total admissions | 3665 | 4652 | |

| Discharged alive | 3244 (88.5) | 4157 (89.4%) | 0.41 |

| Died during admission | 151 (4.1) | 186 (4.0) | |

| Unknown outcome | 270 (7.4) | 309 (6.6) | |

| Excluded (% of total)a | 57 (1.6) | 67 (1.4) | |

| SAM (% of total) | 385 (10.5) | 418 (9.0%) | |

| Discharged alive | 322 (83.6) | 331 (79.2%) | 0.26 |

| Died during admission | 34 (8.8) | 45 (10.8) | |

| Unknown outcome | 29 (7.5) | 42 (10.1) | |

Those with anthropometrics consistent with SAM but documented cardiac or renal pathology were excluded.

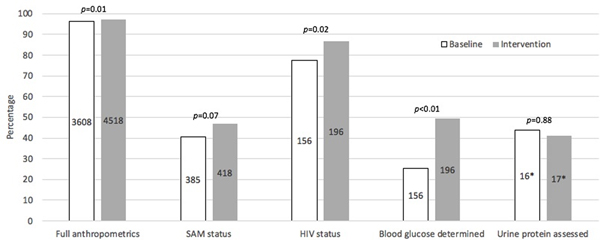

Figure 2 shows overall compliance with documentation of the targeted key components of SAM evaluation and management described in Table 4 between baseline and intervention time periods (including all three PDSA Cycles). Statistical improvement with documentation was seen for full anthropometrics (p=0.01), HIV status (p=0.02) and blood glucose (p<0.01). Although there was a trend towards improvement in documentation of the diagnosis of SAM, it did not reach statistical significance (p=0.07). There was no statistical improvement between the two periods for proteinuria assessment in those with 3+ oedema, although only a total of 33 children had 3+ oedema.

Figure 2.

Proportions of quality gap documentation between baseline (18 September 2018 to 17 March 2019, white bars) and intervention periods (18 September 2019 to 17 March 2020, grey bars). Values centred in the bars are the denominators in the percentage calculations. *Only includes those with 3+ oedema. SAM: severe acute malnutrition.

Appendix 1 presents outcome measures over time via run charts with annotations of cycles. Within the intervention phase, the number of patients with SAM increased from 88 in Cycle A to 199 in Cycle C. Although improvement in Cycles B and C compared with Cycle A were noted for a number of target quality gaps, the only statistically significant improvement was seen for blood glucose documentation (Table 6).

Table 6.

Target quality gap outcomes over three PDSA cycles during the intervention period (18 September 2019 and 17 March 2020).

| Target quality gap | Cycle A (18 Sept to 24 Nov) |

Cycle B (25 Nov to 15 Jan) |

Cycle C (16 Jan to 17 March) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Anthropometrics documented on admission | |||

| At least MUAC | 1000/1026 (97.5) | 1308/1340 (97.6) | 2157/2219 (97.2) |

| At least weight | 1022/1026 (99.6) | 1331/1340 (99.3) | 2207/2219 (99.5) |

| At least height | 1003/1026 (97.8) | 1314/1340 (98.1) | 2189/2219 (98.6) |

| All MUAC, weight and height | 993/1026 (96.8) | 1305/1340 (97.4) | 2155/2219 (97.1) |

| SAM documented by admissiona | 44/88 (50.0) | 58/131 (44.3) | 94/199 (47.2) |

| HIV status documented on dischargeb | 36/44 (81.8) | 50/58 (86.2) | 84/94 (89.4) |

| Blood glucose documented within 24 hrs of admissionb | 18/44 (40.9) | 20/58 (34.5) | 59/94 (62.8)d |

| Proteinuria assessed within 48 hrs of admissionc | 1/3 (33.3) | 1/6 (16.7) | 5/8 (62.5) |

Only for those with SAM based on anthropometrics.

Only for those with SAM documented by admission.

Only for those with 3+ oedema. dp<0.05 by χ2 test comparing outcome of Cycle B or C with Cycle A.

Outcome measures are patient-centred experiences. Process measures describe steps in a system performing as planned. Balance measures are unintended consequences in the system.

Discussion

This study describes a quality improvement programme aimed at improving the recognition and management of SAM in children aged 6–36 months admitted to a tertiary referral hospital in Malawi. Based upon previous studies at this site [9,10] and the experience of local providers, Paediatrics Department leadership at this facility identified a need for improvement of recognition and management of children with complicated SAM, given the high mortality rate in this population. Five specific quality gaps were identified for focused improvement efforts, and three PDSA cycles were conducted over 6 months during the intervention phase to address these gaps. Compared with the same period in the year before these quality improvement activities (Phase 1), significant improvement was noted for three of the five quality gaps in the context of a greater than 20% increase in patient volume during Phase 2. When comparing outcome between the three PDSA cycles, improvement was not consistent. However, given dramatic increases in patient volume with each cycle, maintenance in the coverage of target gaps in this resource-limited setting in the face of an increased workload suggests a positive effect of this quality improvement programme. Considering the cascade of events needed for appropriate care of this unique population, documentation of SAM status and awareness by the medical team remains a key target quality gap.

The ultimate goal of this quality improvement work is to reduce in-hospital mortality for the population of children admitted to this facility with SAM. Compared with the baseline period, there was not a significant change in mortality during the quality improvement intervention period, despite the described progress with the target quality gaps addressed here. This is not surprising given that this study was not powered to assess changes in mortality. Although implementation of guidelines for inpatient management of SAM has the purpose of reducing mortality, incremental improvement in implementation of these guidelines are steps towards the larger goal of reducing mortality that can be assessed over longer time going forward.

A previous study at this site collecting data from December 2011 to May 2012 demonstrated the value of relying on lay personnel to screen for SAM in hospitalised patients, shifting this task away from clinicians and nurses [12]. Since then, this practice has become the standard of care in the KCH paediatric ward. Nutrition assistants (typically holders of secondary-school degrees having completed a short course in nutrition) and nutritionist interns (individuals in a nutrition bachelor’s degree programme) were responsible for nutritional screening during this study. These positions are often poorly paid and general lack supervision by the overburdened management, so absenteeism was rampant and there was little accountability. To avoid large gaps in data collection, the data clerks who were hired as part of the implementation of the paediatric inpatient care database were the individuals who were mainly responsible for the abstraction of data from patients’ charts. They were trained to measure anthropometrics and were instructed to complete and document anthropometrics when this was not done by nutrition assistants or nutritionist interns by the time of a patient’s admission. The baseline data include these assessments, and it is suspected that the added support from the data clerks accounts for the high coverage of anthropometrics during this period (96.2%). One of the goals of the second phase of the quality improvement initiative was to effectively move nutritional assessment from the data clerks to the NRU team, which occurred during Cycles A and B of Phase 2. Unfortunately, the intervention data do not differentiate between assessments completed by NRU staff and data clerks, which is a limitation. With the interventions described here, and despite moving responsibility back to the NRU team, screening significantly improved between the baseline and intervention periods.

A major challenge to implementing these quality improvement efforts was the high turnover of clinical staff, particularly in the Under 5 unit where children arriving at KCH are initially admitted and managed. The provision of training for nurses and rotating clinical interns was a major strategy during this intervention to address knowledge gaps; however, the rotation of learners through the department was not uniform or predictable. This issue of staff turnover in healthcare settings is universal and is particularly draining in resource-limited settings. The implementation of a locally developed checklist for inpatient management of SAM in Rwanda with early evidence for supporting quality improvement initiatives has recently been reported [13]. The checklist included the WHO 10 Steps for Inpatient Management of SAM [5,6], tracking changes in anthropometrics during admission, assessing for adverse reactions to therapeutic feeds and assessing for the criteria for advancing therapeutic feeds [13]. A similar strategy at KCH could ameliorate the challenges of insufficiently trained staff and high staff turnover as checklists are known to standardise and strengthen adherence to implementation of complex but repetitive clinical practices in a variety of contexts [14–16]. Nevertheless, providers must have an understanding of the implications of implementing best practices and the potential consequences of not doing so. In settings such as Malawi where mobile phone technology and understanding of information technology are rapidly improving, an interesting tool that has been demonstrated to improve adherence to guidelines and case-fatality rates is an interactive, scenario-based eLearning platform [17].

Another significant challenge to the implementation of the management steps was communication between NRU staff and clinical staff. NRU staff typically identify patients with SAM, and the expected workflow is that this diagnosis is communicated to clinical staff who can then manage appropriately those with SAM. However, this communication proved challenging for our NRU staff who, while knowledgeable about SAM, may have been considered a lower cadre than the clinicians with higher-level degrees. Clinical staff were reported to be resistant to receiving consultation from ‘lower-tier’ NRU staff, particularly during periods with high volumes of acutely ill children. The diagnosis of SAM may also have been perceived as a burden on the clinical staff as management decisions and tasks may be more complicated for patients with SAM compared with those without it. NRU staff were often frustrated by clinical staff placing a lower priority on the management of SAM or disregarding diagnoses of SAM altogether. If the clinician did not diagnose SAM, the care cascade could not be initiated. Although the team strategised different ways to resolve the issue of poor communication between cadres, it has remained a barrier. Closely related to the issues of staff turnover and poor communication between cadres is the fundamental issue of understaffing. Addressing the problem of understaffing will be a major focus in future, with anticipated secondary effects of improved oversight and mentorship of frontline staff by supervisors, and improved communication between cadres. The challenges described above and the additional barriers to implementation of the quality improvement activities listed in Table 3 are important considerations for quality improvement teams working in similar settings.

A recent report described quality improvement efforts in the care of children with acute malnutrition over 5 years in a rural South African district [18]. The importance of establishing an ‘enabling environment’ as a key factor in reducing in-hospital mortality was emphasised [18]. The concept of using an ‘enabling environment’ for reducing malnutrition is detailed in another report with three principles: (a) “framing, generation, and communication of knowledge and evidence”, (b) “political economy of stakeholders, ideas, and interests” and (c) “capacity (individual, organisational, and systematic) and financial resources.” [19]. In the early stages of quality improvement work at this facility, efforts in each of these three principle areas have begun. The framework challenges us to continue broadening our approach within each of these domains to improve the care of this vulnerable population.

There are notable limitations to this study. It relied upon routinely collected data documented in patient charts and consequently included some incomplete data, which is a reality of quality improvement research. For example, discharge outcome was not documented for 10.1% of patients with SAM during the intervention period. Timely and appropriate administration of therapeutic feeds is an essential component of managing complicated SAM, but this was not assessed. Given that previous studies have demonstrated a high rate of post-discharge mortality in children with SAM in the months after discharge from inpatient programmes [20,21], this study’s focus only on inpatient mortality is also a limitation. Feeding indicators, including frequency, and post-discharge mortality should be assessed in future quality improvement interventions in this population. As noted above, with data clerks completing and documenting anthropometrics when staff failed to do so, the impact that quality improvement interventions (which supported staff responsible for completing anthropometrics) had on anthropometrics coverage could not be adequately assessed. As the referral hospital for the central third of the country, the case mix here may not represent a typical inpatient setting caring for those with complicated SAM at a regional health centre or district hospital. Those with SAM cared for at KCH in this study are probably from a more urban population and with more complicated SAM requiring referral to this facility.

A quality improvement initiative to improve case-finding of SAM and implementation of the WHO 10 Steps for Inpatient Management of SAM at a busy, urban tertiary referral hospital in Malawi is described. Significant reduction of key quality gaps (completion of anthropometrics on admission, documentation of HIV testing results and documentation of blood glucose) represent early progress towards the larger goal of reducing mortality in this population. The processes described here may be relevant to those implementing quality improvement in other resource-limited inpatient settings.

Supplementary Material

Appendix Figure 1. Run charts of process measures with annotation of cycles. (A) The bars show weekly number of patients aged 6–36 months admitted. The black lines show compliance with documentation of full anthropometrics (height, weight and mid-upper-arm circumference) of all patients aged 6–36 months (solid line) and SAM status documentation (i.e. presence or absence of SAM) for those with SAM (dashed line). (B) The black lines show compliance with documentation of HIV status (solid line) and blood glucose (dashed line) for those with SAM. (C) The bars show bi-weekly number of patients with severe oedema (blue) and, of those, the number with urine dipstick documented (green). The black line shows compliance with documentation of urine dipsticks for those with severe oedema. All red lines indicate measure goals.

Acknowledgments

We would like first and foremost like to thank our patients and their caregivers for their involvement in this study, the KCH paediatric staff for their tireless care of these patients, and the data clerks for their diligent management of the patient data. We also thank PACHIMAKE, Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation Malawi, UNC Children’s Foundation, and UNC Project Malawi for the guidance and support which made this project possible. Finally, we thank the late Dr Peter Kazembe for his guidance at the start of this project and for the efforts throughout his life to improve the wellbeing of children in Malawi and throughout the world.

Funding: The use of REDCap was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health [Grant Award Number UL1TR001111].

Abbreviations:

- CO

clinical officer

- EZ

Emergency Zone

- HTC

HIV testing and counselling

- KCH

Kamuzu Central Hospital

- MUAC

mid-upper arm circumference

- NGO

non-government organisation

- NRU

nutritional rehabilitation unit

- PACHIMAKE

Pediatric Alliance for Child Health Improvement in Malawi at KCH and Environs

- PDSA

plan-do-study-act

- SAM

severe acute malnutrition

- WHO

World Health Organization

Biographical notes

Bryan Vonasek is a paediatric infectious diseases fellow at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

Susan Mhango is the lead nutritionist at Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation Malawi, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Heather Crouse is an Associate Professor of Pediatrics in the Section of Pediatric Emergency Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA.

Temwachi Nyangulu is a nurse on the Paediatric Ward of Kamuzu Central Hospital, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Wilfred Gaven is a lecturer in the Faculty of Clinical Medicine, Malawi College of Health Sciences, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Emily Ciccone is an Infectious Diseases Clinical Instructor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Alexander Kondwani is a paediatric clinical officer and MSc student at North West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa.

Binita Patel is an Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine in the Section of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA.

Elizabeth Fitzgerald is an Assistant Professor of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill School of Medicine, and Director of UNC Pediatric Global Health in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

Data availability:

EThe data which support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.World Bank, United Nations Children’s Fund, World Health Organization. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: key findings of the 2020 edition. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/69816/file/Joint-malnutrition-estimates-2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report. New York; 2019. Available from: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberton T, Carter ED, Chou VB, et al. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e901–e908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aborode AT, Ogunsola SO, Adeyemo AO. A crisis within a crisis: Covid-19 and hunger in African children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;104:30–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Guideline: updates on the management of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/95584/9789241506328_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 25 April 2020). [PubMed]

- 6.Ashworth A, Khanum S, Jackson A, et al. Guidelines for the inpatient treatment of severely malnourished children. 2003. Available from: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guide_inpatient_text.pdf (accessed 25 April 2020).

- 7.Malawi Ministry of Health. Guidelines for community-based management of acute malnutrition. 2016. Available from: https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/Malawi-CMAM-Guidelines-Dec2016.pdf

- 8.Eckerle M, Crouse HL, Chiume M, et al. Building sustainable partnerships to strengthen pediatric capacity at a government hospital in Malawi. Front Public Health. 2017;5:183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald E, Mlotha-mitole R, Ciccone EJ, et al. A pediatric death audit in a large referral hospital in Malawi. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vonasek BJ, Chiume M, Crouse HL, et al. Risk factors for mortality and management of children with complicated severe acute malnutrition at a tertiary referral hospital in Malawi. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2020;40:148–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciccone EJ, Tilly AE, Chiume M, et al. Lessons learned from the development and implementation of an electronic paediatric emergency and acute care database in Lilongwe, Malawi. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LaCourse SM, Chester FM, Preidis G, et al. Lay-screeners and use of WHO growth standards increase case finding of hospitalized Malawian children with severe acute malnutrition. J Trop Pediatr. 2015;61:44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck K, Mukantaganda A, Bayitondere S, et al. Experience: developing an inpatient malnutrition checklist for children 6 to 59 months to improve WHO protocol adherence and facilitate quality improvement in a low-resource setting. Glob Health Action. 2018;11:1503785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semrau KEA, Hirschhorn LR, Delaney MM, et al. Outcomes of a coaching-based WHO safe childbirth checklist program in India. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2313–2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:491–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infection in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2725–2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi S, Yuen HM, Annan R, et al. Improved care and survival in severe malnutrition through eLearning. Arch Dis Child. 2019;105:32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider H, van der Merwe M, Marutla B, et al. The whole is more than the sum of the parts: establishing an enabling health system environment for reducing acute child malnutrition in a rural South African district. Health Policy Plan. 2019;34:430–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillespie S, Haddad L, Mannar V, et al. The politics of reducing malnutrition: building commitment and accelerating progress. Lancet. 2013;382:552–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chisti MJ, Graham SM, Duke T, et al. Post-discharge mortality in children with severe malnutrition and pneumonia in Bangladesh . PLoS One. 2014;9:e107663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerac M, Bunn J, Chagaluka G, et al. Follow-up of post-discharge growth and mortality after treatment for severe acute malnutrition (FuSAM study): a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix Figure 1. Run charts of process measures with annotation of cycles. (A) The bars show weekly number of patients aged 6–36 months admitted. The black lines show compliance with documentation of full anthropometrics (height, weight and mid-upper-arm circumference) of all patients aged 6–36 months (solid line) and SAM status documentation (i.e. presence or absence of SAM) for those with SAM (dashed line). (B) The black lines show compliance with documentation of HIV status (solid line) and blood glucose (dashed line) for those with SAM. (C) The bars show bi-weekly number of patients with severe oedema (blue) and, of those, the number with urine dipstick documented (green). The black line shows compliance with documentation of urine dipsticks for those with severe oedema. All red lines indicate measure goals.

Data Availability Statement

EThe data which support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.