Structured Abstract

Objective:

The burden of serious mental illness places a considerable toll on the mental health service system in the US. To date, no research has examined the availability of psychiatric emergency walk-in and crisis services. The goal of this study was to examine temporal trends, geographic variation, and characteristics of psychiatric facilities that provide emergency psychiatric walk-in and crisis services across the US.

Methods:

This study was based on annual (2014–2018) repeated, cross-sectional data from the National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS), a representative survey of public and private mental health treatment facilities in the US.

Results:

Overall, 42.6% percent of all mental health facilities in the US did not offer any mental health crisis services between 2014 and 2018. A third of facilities offered emergency psychiatric walk-in services (33.5%) and just under half provided crisis services (48.3%). When examining population-adjusted estimates, there was a 15.8% (1.52 to 1.28 per 100,000 US adults) and 7.5% (1.86 to 2.01 per 100,000 US adults) decrease in walk-in and crisis services, respectively, from 2014 to 2018. Large geographic variation in service availability was also present.

Conclusion:

A large proportion of psychiatric facilities in the US do not provide psychiatric walk-in or crisis services. Availability of these services is either flat or declining. Disparities, particularly around US borders and coasts, suggest policy efforts could be valuable to ensure equitable availability of services.

It is estimated that 1 in 25 adults in the United States experiences serious mental illness each year (1) and that serious psychological events, including death by suicide (2) are increasing over time. The emergence of COVID-19 and the associated burden on mental health is expected to exacerbate the incidence and prevalence of serious illness and the US mental health system must brace for the impact (3–6).

Unfortunately, hospital Emergency Departments (ED) are currently the frontline provider when triaging mental crises in the US (7–9). First responders and mental health professionals rely on EDs for brief stabilization and/or as a means of obtaining an inpatient bed. However, these settings often lack the resources and privacy needed to manage acute psychiatric events (10), especially when children and people with a developmental disability (9,11) are involved. Psychiatric visits that are not true emergencies are problematic because their length of stay is much longer than medical visits (12). There is even evidence to suggest these visits are increasing in length (12). When psychiatric ED visits are not urgent, they absorb precious healthcare resources and extend wait times for people with acute needs. Two large recent studies suggest a significant proportion of mental health visits to the ED are not urgent (9,13) and could be evaluated and treated in different settings. Therefore, outpatient mental health crisis services play an important role in managing both acute and subacute psychiatric events, especially since EDs are a diminishing resource as the pandemic spreads.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) defines mental health crisis services as “no-wrong-door safety net services” that are “for anyone, anywhere, and anytime” (14). These services provide rapid access to psychiatric evaluation and/or treatment, with the goal of avoiding escalation and preventing immediate harm. Crisis services take many forms, from crisis hotline services to specialized outpatient and hospital-based models. The actual therapeutic methods employed by these settings vary based on setting and expertise. Generally, they employ methods such as verbal de-escalation and psychotherapeutic strategies, PRN medications, outpatient and inpatient referrals, and treatment planning. Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Programs (CPEP) have become (15) increasingly important models of hospital-based psychiatric care. These programs have a trained group of mental health professionals that provide medical and psychiatric evaluation, oftentimes offering extended observation beds for short-term evaluation. CPEP services can even include both mobile and in-home services that provide longer-term (often 1–2 months) education, therapy, and medication management.

Two important in-person clinical services in the continuum of crisis care include psychiatric walk-in and crisis services. Psychiatric walk-in services reflect the availability of immediate, unscheduled, in-person assessment whenever the outpatient or inpatient facility is in operation (16,17). There is substantial heterogeneity in the services offered by walk-in models, ranging from treatment for ongoing symptom management (e.g., follow-up medication management) or assessment of an acute incident (e.g., determining if a referral for inpatient is warranted). Walk-in models have been shown to be helpful for improving access to care among traditionally-underserved groups who can struggle to maintain connections to their outpatient providers (18). At a minimum, this service reflects the facility’s willingness and capacity to accept urgent referrals.

As opposed to walk-in models, crisis services actively respond to mental health events, often through community outreach. The treatment provided depends on the nature of the referral and disciplines (e.g., social work, psychiatric nurse) reflected on the team. Many times, crisis services respond to acute events by providing brief interventions (e.g., brief psychotherapy, de-escalation). Crisis Services often partner with local law enforcement as well, termed Crisis Intervention Teams, in an effort to improve outcomes such as minimizing incarceration where possible. A recent Cochrane review demonstrated crisis services are promising and can reduce inpatient hospitalizations (19).

No recent epidemiologic research has examined the availability of these community-based approaches to crisis prevention and management in the US. A population-level understanding of the availability of these services is important for public health planning, particularly in light of the strain that COVID-19 places on healthcare systems. To address this gap, the current study has three aims: to examine 1) changes in the availability of walk-in models and crisis services, between 2014 and 2018, across the US; 2) examine the characteristics of facilities that offer these crisis intervention services, and; 3) evaluate regional and state-to-state geographical variation in the availability of crisis services.

Methods

Sample

Data for this study came from the National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS). The N-MHSS is a yearly, repeated cross-sectional survey, sponsored by SAMHSA, of all known public and private mental health treatment facilities in the US (http://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/n-mhss-national-mental-health-services-survey) (20). Its primary purpose is to serve as an annual census of all mental healthcare facilities in the US, which is curated into the National Directory of Mental Health Treatment Facilities (https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2020-national-directory-mental-health-treatment-facilities) and the Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator (https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov). The survey is completed by facility staff, including the director or an administrator. The most recent five years of publicly released N-MHSS data were used for this study. Data released prior to that had substantial missingness (2010) or fully omitted (2012) an outcome variable used in the current study. The mean N-MHSS response rate, between 2014 and 2018, was 90%. It’s important to note that the N-MHSS is a de-identified survey. As such, it is not possible to identify how many unique facilities are represented. Further information about the N-MHSS can be found at https://wwwdasis.samhsa.gov/dasis2/N-MHSS.htm.

The other data used in this study were retrieved from the US Bureau of Census (21). Census data served as the denominator when calculating population-based rates of services per 100,000 adults, ≥18 years of age, in the US. Census data were joined with the N-MHSS at the state-level for each year. Because N-MHSS and Census data are publicly available and fully de-identified, the governing institutional review board does not consider this study human subjects research.

Exclusion Criteria

Facilities were removed if they were listed as residential treatment facilities or owned by Veterans Affairs. They were excluded since they are healthcare facilities available to only those who live onsite, while VA services only serve veterans. Since neither service is available to the general public, they were removed. Facilities located in the Virgin Islands and other American territories were also excluded. This resulted in an average of 10,032 facilities per year.

Variables

Outcomes

The primary study outcomes were the reported availability of 1) psychiatric emergency walk-in, and/or 2) crisis services. Psychiatric emergency walk-in services were captured in a checklist of services list on the N-MHSS questionnaire (22). SAMHSA defines psychiatric emergency walk-in services as “specifically trained staff to provide psychiatric care, such as crisis intervention, in emergency situations on a walk-in basis to enable the individual(s), family members and friends to cope with the emergency while helping the individual function as a member of the community to the greatest extent possible” (22). The N-MHSS survey assessed crisis services with a standalone question: “Does this facility operate a crisis intervention team to handle acute mental health issues at this facility or offsite?” Unfortunately, no further definition for this term is provided to survey respondents or in the N-MHSS codebook.

Characteristics of Mental Health Facilities

A host of facility-related descriptors were available. These included the facility setting (psychiatric hospital, separate inpatient psychiatric unit of a general hospital, community mental health center, partial hospitalization/day treatment facility, outpatient mental health facility, multi-setting mental health facility, and other), whether the facility was licensed by a state mental health agency (yes/no), and type of ownership (private for-profit, private not-for-profit, public). Information about insurance acceptance was also available, including whether the facility accepted Medicaid (yes/no), whether they used a sliding scale for fees (yes/no) based on household income, and provision of substance use services (yes/no).

Analysis

To address the first study aim, two analyses were performed. First, a random effects logistic regression model was employed to evaluate changes in the probability of a facility offering a crisis service between 2014 and 2018 using data solely from the N-MHSS. A random effect was placed on state, to account for state-level clustering. Second, population rates (calculated as the number of facilities that offer an identified crisis service per 100,000 adults in the US per year) were reported descriptively and visually. For the second and third aims, descriptive statistics were used to better understand the characteristics of facilities that offered crisis services. To understand state-to-state variability, national maps were generated. Census data were used in these maps, as the denominator, to calculate population rates (per 100,000 adults) at the state level. Between-state variations in the census adjusted availability of the identified service were displayed using a five-point color-coding scheme, which was based on binning the population rates into quintiles. Only data from 2018 were analyzed for Aims 2 and 3, to provide the most up-to-date information. All analyses were conducted in STATA 15.0 (College Station, TX). Since there were very little missing data (<3% on all variables), this study employed complete case analysis.

Results

Between 2014 and 2018, one-third of all mental health facilities offered emergency psychiatric walk-in services (N=16,767; 33.5%), and just under half provided crisis services (N=24,136; 48.3%). When a facility offered walk-in services, they often provide crisis services as well (72.8%). When crisis services were offered, walk-in services were provided half the time (50.5%). Overall, 42.6% of facilities did not offer either service, 33.0% offered one of the services, and 24.4% offered both services.

Trends in Crisis Service Availability

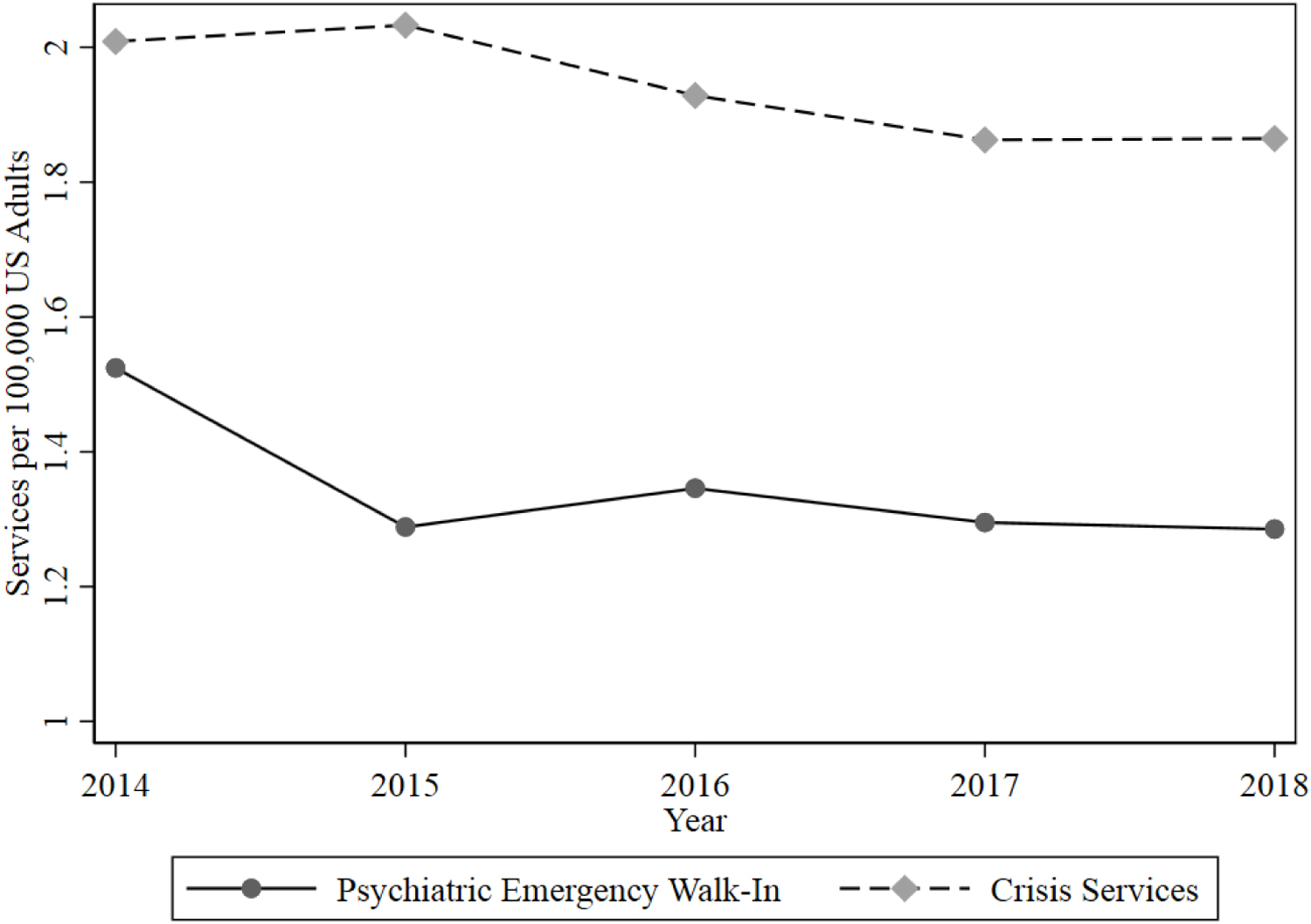

The proportion of facilities that offered walk-in services slightly declined between 2014 (36.7%) and 2018 (33.7%). Results from the random effects logistic model demonstrated a decrease in the probability of facilities offering walk-in services for 2015–2018 when compared to 2014 (all p<.001). For crisis services, there was a significant decrease in 2015, when compared to 2014 (p=.04). However, there was no significant change thereafter, when compared to 2014 (see Table 1 for regression estimates). The census-adjusted estimates of services per 100,000 adults ≥18 years of age are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. Between 2014 and 2018 there was a 15.8% (1.52 to 1.28 facilities per 100,000 adults) and 7.5% (2.01 to 1.86 facilities per 100,000 adults) decrease in walk-in and crisis services, respectively.

Table 1:

Proportion of Facilities with Psychiatric Walk-In and/or Crisis Services in the US

| Facilities offering Psychiatric Walk-In Service | Facilities offering Crisis Team Services | Total Facilities | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | M | OR | 95% CI | N | % | M | OR | 95% CI | N | |

| 2014 | 3,732 | 36.73 | 1.52 | Reference | 4,918 | 48.19 | 2.01 | Reference | 10,247 | ||

| 2015 | 3,184 | 30.06* | 1.29 | 0.73* | 0.69, 0.77 | 5,024 | 47.49* | 2.03 | 0.96 * | 0.93, 0.99 | 10,598 |

| 2016 | 3,357 | 33.50* | 1.34 | 0.86* | 0.82, 0.90 | 4,810 | 48.04 | 1.93 | 0.99 | 0.94, 1.04 | 10,026 |

| 2017 | 3,258 | 33.85* | 1.29 | 0.88* | 0.83, 0.93 | 4,686 | 48.71 | 1.86 | 1.02 | 0.97, 1.08 | 9,629 |

| 2018 | 3,262 | 33.77* | 1.28 | 0.88* | 0.82, 0.93 | 4,732 | 49.04 | 1.86 | 1.04 | 0.97, 1.11 | 9,664 |

| Total | 16,793 | 33.54 | 1.34 | --- | 24,170 | 48.28 | 1.93 | --- | 50,160 | ||

change since 2014, p<.05; Note: M = Mean services per 100,000 adults in the US; OR (95% CI) indicate Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals for random effects logistic regression model for each year compared to the year 2014; Percentages reflect the proportion of facilities, per year, that offer the identified service; Psychiatric Walk-In and Crisis Intervention Team services are not mutually exclusive

Figure 1:

Changes in the Availability of Crisis Services in the US

Characteristics of Crisis Facilities

Shown in Table 2, hospitals and CMHCs most frequently offered psychiatric walk-in and crisis services (45–67%), whereas all other settings provided these services less frequently (except 50.4% of multi-setting facilities offered crisis services). Most (about 80%) facilities that provided either crisis service were certified by the state. Public facilities were more likely to provide both services, especially when compared to private for-profit facilities. Almost all facilities that offered walk-in and/or crisis services (>97%) accepted Medicaid, although substantially fewer facilities provided services at a sliding scale (68%). About two-thirds of facilities that provided walk-in or crisis services offered substance use-related services.

Table 2:

Characteristics of Facilities with Psychiatric Walk-In and/or Crisis Services in the US, 2014–2018

| Facilities offering Psychiatric Walk-In Service | Facilities offering Crisis Team Services | Total Facilities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 3,169 | 27.34 | 4,385 | 37.82 | 11,612 | 23.15 |

| Midwest | 3,938 | 31.03 | 6,153 | 48.46 | 12,715 | 25.35 |

| South | 6,004 | 41.15 | 7,731 | 53.01 | 14,612 | 29.13 |

| West | 3,682 | 32.90 | 5,901 | 52.73 | 11,221 | 22.37 |

| Setting | ||||||

| Psychiatric Hospital | 1,656 | 48.72 | 1,675 | 49.34 | 3,406 | 6.79 |

| Separate Hospital | 3,060 | 55.26 | 2,774 | 50.14 | 5,542 | 11.05 |

| Community Mental Health Clinic | 6,350 | 56.56 | 9,192 | 67.38 | 13,658 | 27.23 |

| Partial Hospitalization | 73 | 4.84 | 570 | 37.85 | 1,511 | 3.01 |

| Outpatient | 5,011 | 21.35 | 8,744 | 37.24 | 23,525 | 46.90 |

| Multi-Setting Facility | 576 | 26.10 | 1,112 | 50.45 | 2,212 | 4.41 |

| Other | 67 | 22.11 | 103 | 33.88 | 306 | 0.61 |

| Licensed by State Mental Health Agency | ||||||

| No | 3,247 | 28.71 | 4,386 | 38.25 | 11,337 | 23.22 |

| Yes | 13,181 | 35.22 | 19,266 | 51.46 | 37,497 | 76.78 |

| Ownership | ||||||

| Private For-Profit | 2,594 | 29.30 | 3,449 | 38.99 | 8,875 | 17.69 |

| Private Non-Profit | 9,954 | 30.82 | 15,308 | 47.38 | 32,358 | 64.51 |

| Public | 4,245 | 47.61 | 5,413 | 60.75 | 8,927 | 17.80 |

| Accepts Medicaid | ||||||

| No | 276 | 1.65 | 521 | 2.17 | 1,826 | 3.66 |

| Yes | 16,422 | 98.35 | 23,533 | 97.83 | 48,002 | 96.34 |

| Accepts Sliding Scale | ||||||

| No | 5,336 | 31.90 | 7,750 | 32.14 | 18,905 | 37.82 |

| Yes | 11,392 | 68.10 | 16,364 | 67.86 | 31,088 | 62.18 |

| Offers Substance Use Services | ||||||

| No | 5,378 | 32.03 | 8,711 | 36.04 | 21,892 | 43.64 |

| Yes | 11,415 | 67.97 | 15,459 | 63.96 | 28,268 | 56.36 |

Geographic Location of Crisis Facilities

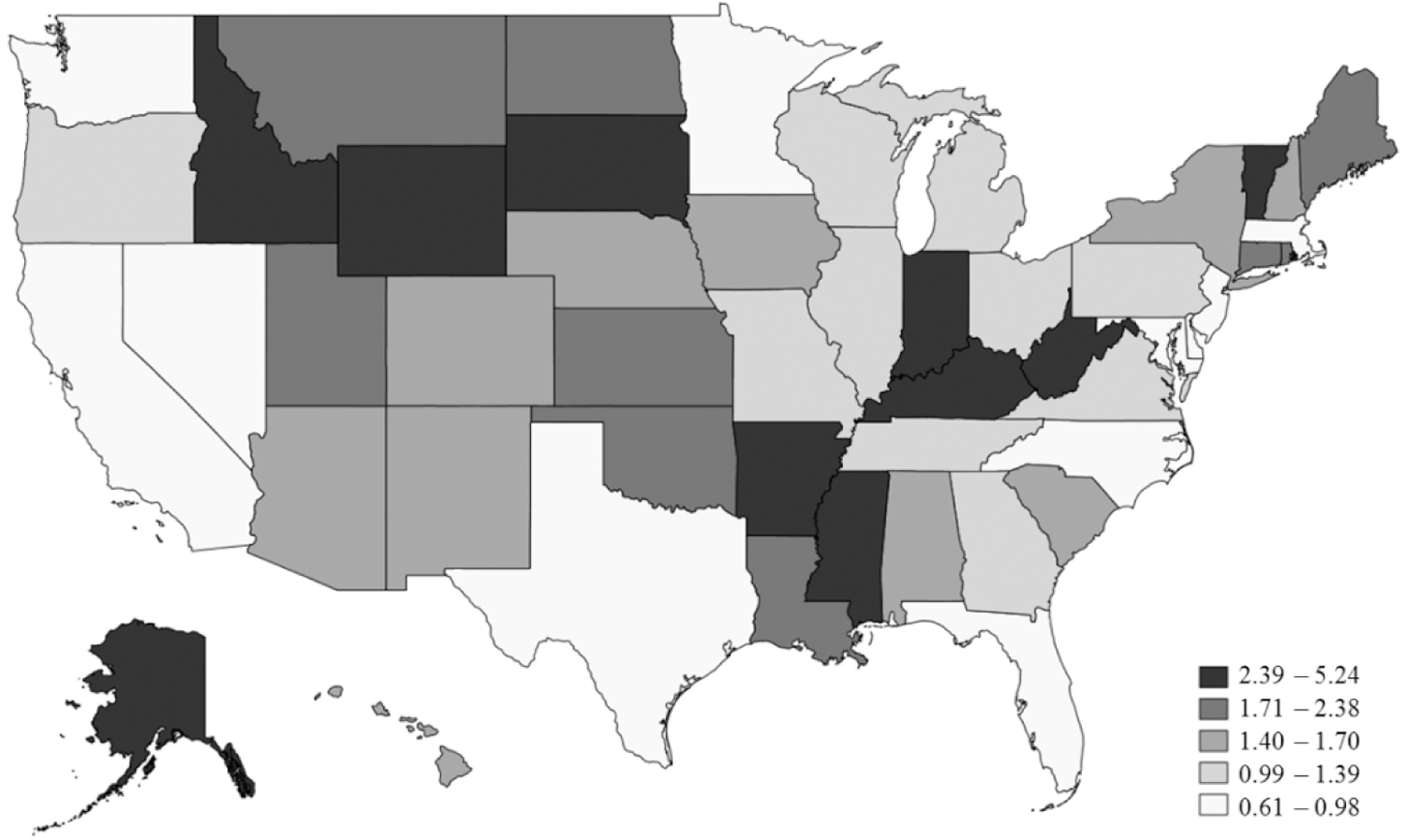

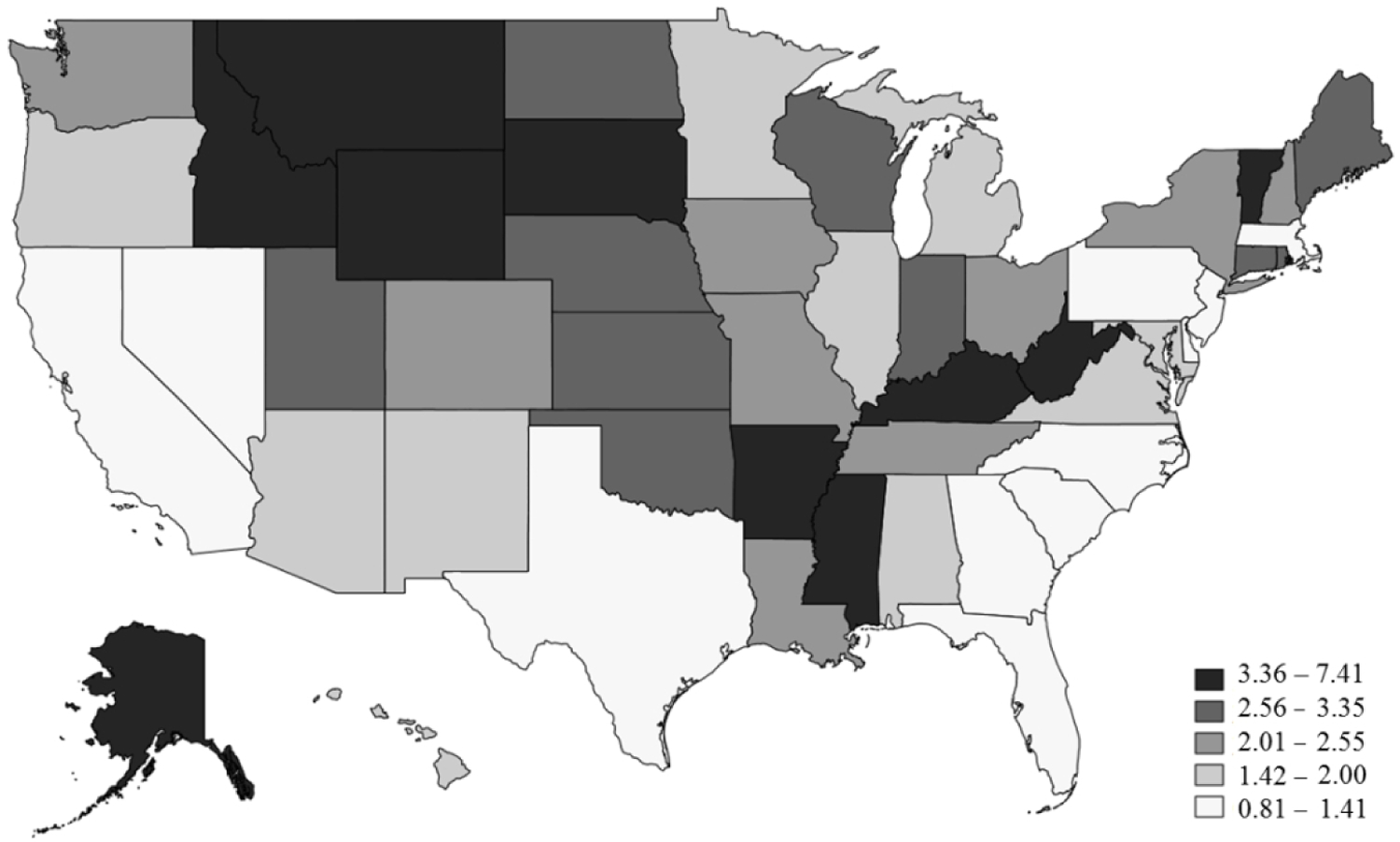

Table 2 shows the regional differences in the proportion of facilities that offered crisis services. Using just the NMHSS data, facilities in the South offered the highest proportion of both services, whereas the Northeast had the lowest. Figures 2 and 3 display state-to-state variability in walk-in and crisis services, respectively, 2018. State-specific estimates, for 2018, are shown in the Online Supplement, Supplemental Table. Low availability of both walk-in and crisis services occurred for Massachusetts, New Jersey, Delaware, North Carolina, Florida, Texas, Nevada, and California. We believe the census-based estimates provide the greatest understanding of geographic availability, as opposed to the regional proportions (based solely on NMHSS data), because those figures account for population density.

Figure 2:

Availability of Psychiatric Emergency Walk-In Services, 2018

**services per 100,000 US adults

Figure 3:

Availability of Crisis Services, 2018

**services per 100,000 US adults

Discussion

Overall, more than 40% of all mental health facilities in the US did not offer the mental health crisis services evaluated in this study between 2014 and 2018. One-third offered emergency psychiatric walk-in services and fewer than half provided crisis services; only a quarter offered both. After 2014, there was a significant decrease in the probability of a facility offering psychiatric emergency walk-in care. No significant change was observed in crisis services. These findings are disconcerting in the context of recent increases in suicide and opioid-related deaths (23,24). These data raise concerns about the availability of services, particularly for those who do not access outpatient services in a traditional way, to manage acute psychiatric events either passively (through referrals and walk-ins) or actively (through outreach, such as crisis services).

There was substantial geographic variation in the availability of psychiatric walk-in and crisis services. This finding reveals a lack of national policies or standards for crisis services. In general, the Northeast region had the lowest proportion of services, seen in Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Delaware. However, additional states outside of the Northeast had a disparity of services, including North Carolina, Florida, Texas, Nevada, and California. This finding raises concerns about an underdeveloped psychiatric emergency infrastructure in these regions.

These findings are especially pertinent in the era of COVID-19. Even prior to the pandemic, EDs in the US were stretched beyond their capacity (25–27). As the pandemic spreads, the emergency management system has fewer resources than ever to attend to those with mental health issues. These data suggest the need for licensed mental health facilities throughout the US to expand the provision of crisis services. This is particularly the case for outpatient settings, which are the largest segment of the mental health system, but where less than one-quarter provide walk-in services and about one-third provided crisis services. As state and federal governments are generating and applying stimulus packages to address gaps in the healthcare system secondary to COVID-19, attention could be paid towards funding training and delivery of crisis services in general, since mental health care should be fully integrated into a systems-based approach to disaster response and recovery (28). Critically, increased availability of crisis services and facilities alone are not sufficient to meet the needs of individuals in psychiatric crises. As described by Hogan and Goldman, broader changes in policy and funding are needed. This includes an increase in authorization and appropriation of funds by Congress, a 5% Mental Health Block Grant, increased funding for research and evaluation, additional payment mechanisms, and a central coordinating role for Congress (29).

This study should be interpreted in light of its strengths and weaknesses. In terms of strengths, data from this study were nationally representative. Survey and item-response rates were high. The findings are novel, timely, and important for national and state policy. A critical limitation was the lack of details about how, and for whom, crisis services were delivered, including the number of individuals actually served (as opposed to the facility capacity). Another important limitation was that details about additional crisis services were limited. This includes services like hotlines, crisis stabilization beds, comprehensive psychiatric emergency programs, peer supports, EmPATH Units, and psychiatric observations that were not measured by the N-MHSS or this study. Thus, this study does not reflect the true availability of crisis services in the US nor does it demonstrate the efficacy of such interventions. The exclusion of VA administration, given veterans face unique needs and require an in-depth investigation, is another limitation. Finally, there was some conceptual overlap between the items, used to capture walk-in vs. crisis services, since on vs. offsite crisis services could not be differentiated. Respondents may have selected both items/services when only walk-in services were available (since they may have considered onsite crisis services the same as walk-in services).

Conclusion

In summary, a large proportion of US mental health facilities are not delivering the mental health crisis services evaluated in this study. There was a decrease in the population-adjusted availability of crisis services between 2014 and 2018. The great state-to-state variability reveals the need for a national approach to crisis training and service delivery. It also raises questions about the fitness of the US to provide acute mental health care services both during and after the pandemic.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Nearly half of all mental health facilities in the US did not offer any mental health crisis services between 2014 and 2018.

There was a 15.8% (1.52 to 1.28 per 100,000 US adults) and 7.5% (1.86 to 2.01 per 100,000 US adults) decrease in walk-in and crisis services, respectively, from 2014 to 2018.

Disparities, particularly around US borders and coasts, suggest policy efforts could be valuable to ensure equitable availability of services.

Acknowledgments:

Work on the current manuscript was in part supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U54 HD079123).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest or competing interests.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA): Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019. Available from: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, Warner M: Suicide rates in the United States continue to increase (NCHS Data Brief No. 309). Hyattsville, Maryland, US, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db309.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keeter S: People financially affected by COVID-19 outbreak are experiencing more psychological distress than others. Washington, DC, Pew Research Center, 2020. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/30/people-financially-affected-by-covid-19-outbreak-are-experiencing-more-psychological-distress-than-others/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfefferbaum B, North CS: Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 510–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holingue C, Badillo-Goicoechea E, Riehm KE, et al. : Mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic among US adults without a pre-existing mental health condition: Findings from American trend panel survey. Prev Med (Baltim) 2020; 139: 106231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holingue C, Kalb LG, Riehm KE, et al. : Mental Distress in the United States at the Beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Public Health 2020; 110: 1628–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine: Pediatric and adolescent mental health emergencies in the emergency medical services system. Pediatrics 2011; 127: e1356–e1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeller SL: Treatment of psychiatric patients in emergency settings. Prim Psychiatry 2010; 17: 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalb LG, Stapp EK, Ballard ED, et al. : Trends in psychiatric emergency department visits among youth and young adults in the US. Pediatrics 2019; 143: e20182192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shattell MM, Andes M: Treatment of persons with mental illness and substance use disorders in medical emergency departments in the United States. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2011; 32: 140–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalb LG, Stuart EA, Vasa RA: Characteristics of psychiatric emergency department use among privately insured adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2019; 23: 566–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santillanes G, Axeen S, Lam CN, et al. : National trends in mental health-related emergency department visits by children and adults, 2009–2015. Am J Emerg Med 2020; 38: 2536–2544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molina-López A, Cruz-Islas JB, Palma-Cortés M, et al. : Validity and reliability of a novel Color-Risk Psychiatric Triage in a psychiatric emergency department. BMC Psychiatry 2016; 16: 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.SAMHSA: National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care - Best Practice Toolkit. Rockville, MD, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/national-guidelines-for-behavioral-health-crisis-care-02242020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan AM, Rivera J: Profile of a comprehensive psychiatric emergency program in a New York City municipal hospital. Psychiatr Q 2000; 71: 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroll DS, Chakravartti A, Gasparrini K, et al. : The walk-in clinic model improves access to psychiatry in primary care. J Psychosom Res 2016; 89: 11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Runnels P: Case studies in public-sector leadership: Addressing the problem of appointment nonadherence with a plan for a walk-in clinic. Psychiatr Serv 2013; 64: 404–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroll DS, Wrenn K, Grimaldi JA, et al. : Longitudinal Urgent Care Psychiatry as a Unique Access Point for Underserved Patients. Psychiatr Serv 2019; 70: 837–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy SM, Irving CB, Adams CE, et al. : Crisis intervention for people with severe mental illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Brown JD: Availability of Integrated Primary Care Services in Community Mental Health Care Settings. Psychiatr Serv 2019; 70: 499–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Census Bureau: American Community Survey 2014–2018 5-Year Data Release. Suitland, Suitland-Silver Hill, MD, United States Census Bureau, 2019. Available from: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2019/acs-5-year.html [Google Scholar]

- 22.SAMHSA: Definitions for Terms Used in the N‑MHSS Questionnaire. Rockville, MD, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019. Available from: https://info.nmhss.org/Definitions/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith HIVDN: Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2017–2018. Hyattsville, Maryland, US, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db330-h.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, Warner M: Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2017. 2018. Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/60894 [PubMed]

- 25.Salinsky E, Loftis C: Shrinking Inpatient Psychiatric Capacity: Cause for Celebration or Concern? Washington, DC, National Health Policy Forum, 2007. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560013/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alakeson V, Pande N, Ludwig M: A plan to reduce emergency room ‘boarding’of psychiatric patients. Health Aff 2010; 29: 1637–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nitkin K: The Changing Dynamics of Emergency Psychiatric Care. Dome - Johns Hopkins Medicine Family. 2018; Available from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/articles/the-changing-dynamics-of-emergency-psychiatric-care [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gostin LO, Viswanathan K, Altevogt BM, et al. : Crisis Standards of Care: A Systems Framework for Catastrophic Disaster Response: Volume 1: Introduction and CSC Framework. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2012. Available from: http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13351 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hogan MF, Goldman ML: New Opportunities to Improve Mental Health Crisis Systems. Psychiatr Serv 2021; 72: 169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.