Abstract

Objective.

Iatrogenic laryngotracheal stenosis (iLTS) is the pathologic narrowing of the glottis, subglottis, and/or trachea secondary to intubation or tracheostomy related injury. Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are more likely to develop iLTS. To date, the metabolomics and phenotypic expression of cell markers in fibroblasts derived from patients with T2DM and iLTS are largely unknown.

Study Design.

Controlled in vitro cohort study.

Setting.

Tertiary referral center (2017-2020).

Methods.

This in vitro study assessed samples from 6 patients with iLTS who underwent surgery at a single institution. Fibroblasts were isolated from biopsy specimens of laryngotracheal scar and normal-appearing trachea and compared with controls obtained from the trachea of rapid autopsy specimens. Patients with iLTS were subcategorized into those with and without T2DM. Metabolic substrates were identified by mass spectrometry, and cell protein expression was measured by flow cytometry.

Results.

T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts had a metabolically distinct profile and clustered tightly on a Pearson correlation heat map as compared with non-T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts. Levels of itaconate were elevated in T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts. Flow cytometry demonstrated that T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts were associated with higher CD90 expression (Thy-1; mean, 95%) when compared with non-T2DM iLTS-scar (mean, 83.6%; P = .0109) or normal tracheal fibroblasts (mean, 81.1%; P = .0042).

Conclusions.

Scar-derived fibroblasts from patients with T2DM and iLTS have a metabolically distinct profile. These fibroblasts are characterized by an increase in itaconate, a metabolite related to immune-induced scar remodeling, and can be identified by elevated expression of CD90 (Thy-1) in vitro.

Keywords: laryngotracheal stenosis, myofibroblast, fibroblast subsets, CD34, CD90, Thy-1, FAP, subglottic stenosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, T2DM

Laryngotracheal stenosis results in cicatricial airway scar that affects voice and breathing, frequently progressing to respiratory failure.1 Iatrogenic laryngotracheal stenosis (iLTS), secondary to postintubation or posttracheostomy injury, is the most prevalent etiology.2 Patients with iLTS require more frequent surgical intervention, including temporary and permanent tracheostomy.2,3 The propensity for severe disease in iLTS is in part due to the biology of pathologic fibroblasts and increased comorbidities, which adversely affect wound healing.4 The most prevalent comorbidity in iLTS is type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which is present in up to 53% of all patients with iLTS.2,5,6 Clinically, patients with T2DM are more likely to develop acute laryngeal injury7 as well as interarytenoid scar resulting in posterior glottic stenosis.6 Biologically, T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts are more contractile and metabolically distinct than non-T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts.8 With a rising incidence of T2DM nationally,9 there is a growing need to understand how T2DM affects iLTS-scar fibroblasts and wound healing in laryngotracheal injury.

The metabolic pathways involved in T2DM iLTS-scar pathogenesis remain largely unknown. Metabolomics, or the study of metabolite substrates, can isolate unique metabolic pathways that are critical in fibrotic diseases such as iLTS.10,11 In T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts, there is an increased mitochondria energy demand as compared with non-T2DM iLTS, suggesting a role for metabolic alteration in disease.4 In other diseases, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, lung biopsy metabolomics analyzed through mass spectrometry show alterations in multiple metabolic pathways when compared with nondiseased controls.12 Moreover, unique metabolic profiles are present in asthma-related airway fibrosis and phenotypically correlate with distinct cellular markers allowing for quantification of fibroblasts subsets.13 Elucidating the metabolic profile of T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts may provide insight into iLTS pathogenesis.

Identifying activated fibroblast subsets helps to distinguish the pathologic effector cell responsible for fibrotic disease.14-16 Many studies have defined fibroblast subsets based on expression of phenotypical intra- and extracellular markers. For instance, fibroblast activation protein (FAP), a surface glycoprotein, is one marker expressed on fibroblasts that is linked to pathologic phenotypes in other fibrotic diseases.17,18 Murine models of rheumatoid arthritis also contain pathologic synovial fibroblast subsets that express FAP+CD90+ via flow cytometry and are associated with inflammation.17 CD90 (Thy-1) expression is further elevated in fibroblasts derived from thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy (formerly known as Graves’-associated ophthalmopathy), which are more contractile than non-CD90+ fibroblasts.19 CD34, an extracellular marker prevalent on undifferentiated progenitor cells, is also seen on fibroblasts, and may be another marker for activated fibroblasts in wound healing.20 Identifying cell surface markers in T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts will allow us to identify pathologic subsets driving disease, which can be a target for intervention.

We performed a discovery study to investigate the metabolic profiles of T2DM and non-T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts. We hypothesized that T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts have a unique and metabolic profile distinct from non-T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts and nonscar fibroblasts. We further hypothesized that T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts have specific cell surface markers that can identify activated fibroblast subsets responsible for a more severe phenotype in T2DM iLTS.

Methods

Fibroblast Isolation and Cell Culture

Endoscopic biopsy samples of airway scar or normal tissue were taken from 6 patients following informed consent in accordance with the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board (NA_00078310). Patients with iLTS were divided into those with and without a preoperative diagnosis of T2DM. All primary fibroblasts were isolated, cultured, and expanded as previously described.21,22 In brief, biopsy specimens were cut into Petri dishes with a scalpel blade. Cells were grown in standard Dulbecco’s modified Eagle media + 10% fetal bovine serum + 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Thermo Scientific).22 Passages 0 to 2 were used for the duration of this study. Normal controls were derived from either nonscar tracheal mucosa in patients with non-T2DM iLTS or autopsy specimens processed within 24 hours of death.23

Mass Spectrometry Metabolomics

Fibroblasts (passages 1 and 2) were passaged onto 10-cm Petri dishes under standard culture conditions. Fibroblasts were grown to confluence, washed twice with phosphate buffered saline, and then collected by mass spectrometer–grade methanol (80%) and a cell scraper. Samples were stored in a −80 °C freezer until all cell lines were collected to minimize the freeze-thaw cycle and perform analysis in bulk. Once thawed, samples were sonicated (Hielscher Ultrasonic Technology) in three 1-second pulses to release cellular contents and placed on a rotator (Thermo Scientific) at low speed overnight. Samples were then centrifuged at 4 °C and the supernatant collected. Cell pellets were isolated and refrozen at −80 °C for total protein quantification. The supernatant (metabolite containing) was dehydrated with nitrogen gas at low flow until there was a 50% reduction in volume. Samples were again centrifuged to remove additional cellular debris, and the supernatant was reconstituted in mass spectrometer–grade acetonitrile. Samples were then analyzed with a Sciex 5500 quadrupole LC/MS mass spectrometer.24 Sufficient data quality was available for 71 metabolites (Supplemental Table S1, available online) based on peak expression. Fibroblasts were grouped by etiology: non-T2DM iLTS-scar (n = 3), T2DM iLTS-scar (n = 3), and normal tracheal biopsies from patients with iLTS (n = 2). Each metabolite peak intensity (mz/rt) was normalized through total protein (μg/mL) and analyzed with MetaboAnalyst 4.0 software.25,26

For total protein concentration, sample pellets were thawed and lysed with an AllPrep RNA/Protein kit (Qiagen). Total protein was then measured with the Qubit Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific).27 Metabolite peaks were subsequently normalized relative to total protein concentration.

Flow Cytometry

Cultured fibroblasts (passages 0-2) were grown in culture to 80% to 90% confluence and trypsinized, as previously described.4 Single-cell suspensions were aliquoted to a 96-well plate. Cells were stained with the following antibody panel: LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua, CD31 (PECAM) Brilliant Violet 421 (303124; BioLegend), CD34 PerCP-CY5.5 (343612; BioLegend), FAPa PE (FAB3715P-025; R&D Systems), CD90 Alexa Fluor 647 (328120; BioLegend), and PDGFR (platelet-derived growth factor receptor) PE/Cy7 (323508; BioLegend). After staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized. Single-stained and florescence minus one–stained samples were used as controls for gate selection. Viability Aqua–negative (live) cells were subsequently evaluated by percentage population of fibroblasts (FAP+). Fibroblast cells line were grouped according to etiology (n = 3), with rapidly processed autopsy tracheal mucosa–derived nonscar fibroblasts used as controls. All analyses were performed in FlowJo Flow Cytometry Analysis Software (Treestar, Version 10.7.1 for Mac).

Statistical Analysis

Metabolomic data were analyzed through standard unpaired t tests for direct comparison between T2DM and non-T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts. A volcano plot—log2(fold change) versus statistical significance (log10[P], P < .05)—was performed to determine metabolites that were elevated in T2DM versus non-T2DM iLTS fibroblasts. A Pearson R coefficient was calculated for sample and metabolite heat map correlations. Partial least squares discriminant analysis was performed, where R2 is an estimate of fit and Q2 is an estimate of predictive ability of the model and is calculated via cross-validation.28 Data analysis was performed with the MetaboAnalyst 4.0 metabolomic web server (metaboanalyst.ca).26

Flow cytometry results were presented as percentage expressed (mean ± SEM). Multiple groups were compared through analysis of variance with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons. Significance criterion for all analyses was set at P < .05. Data analysis was performed with Prism software (GraphPad, Version 8).

Results

Experimental Cohort

Patient demographics were similar between groups (Table 1). No significant differences were noted in age, sex, or BMI. Patients with T2DM and iLTS had higher Charlson Comorbidity Index than those with non-T2DM iLTS and normal tracheal biopsies.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics.a

| T2DM (n = 3) |

Non-T2DM (n = 3) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 54 (38-72) | 48.3 (29-64) | .84 |

| Sex: female | 3 (100) | 2 (66) | .16 |

| Body mass index | 35.6 (26-49) | 32.3 (29-39) | .13 |

| Hemoglobin A1C | 6.3 (6.1-6.7) | ||

| Tobacco use | |||

| Current | 0 | 0 | |

| Former | 1 | 1 | |

| Never | 2 | 2 | |

| Cotton-Meyer grade | .2733 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 2 | 3 | |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | |

| History of tracheostomy | 1 | 3 | |

| Medication | |||

| Metformin | 2 | ||

| Insulin | 2 | ||

| Oxygen therapy | 2 | 0 | |

| Inhaled steroids | 0 | 0 | |

| PPI | 1 | 0 | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Asthma | 0 | 0 | |

| COPD | 0 | 0 | |

| Depression | 1 | 1 | |

| GERD | 2 | 0 | |

| Hemiplegia | 1 | 0 | |

| Hypertension | 2 | 2 | |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 0 | 0 | |

| Solid tumor | 0 | 0 | |

| Inflammatory tissue disease | 0 | 0 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 5 (4-8) | 1.3 (0-5) | .006 |

| Level of stenosis | |||

| Posterior glottis | 2 | 0 | |

| Subglottic | 2 | 3 | |

| Tracheal | 0 | 1 | |

| Multilevel | 1 | 1 |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Blank cells indicate not applicable. Values are presented as mean (range) or No. (%).

T2DM iLTS-Scar Fibroblasts Exhibit a Unique Metabolic Fingerprint vs Non-T2DM iLTS-Scar and Control Fibroblasts

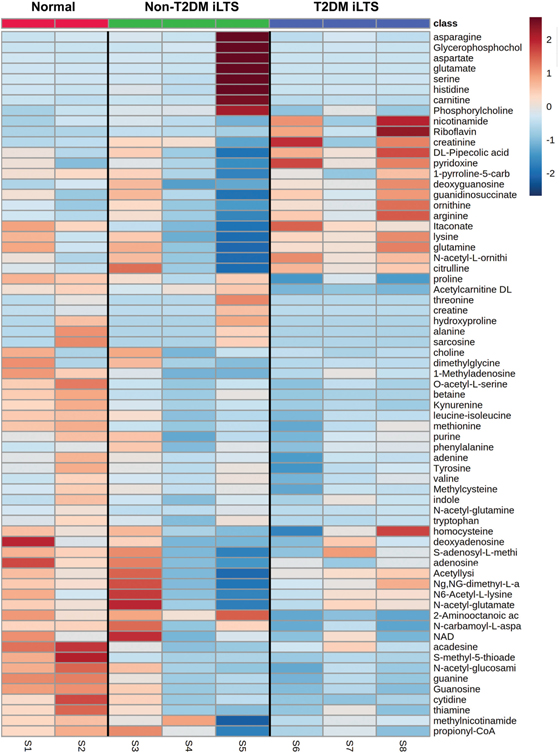

A Pearson coefficient heat map of samples relative to metabolites illustrates distinct metabolite fingerprints in T2DM iLTS-scar and nonscar fibroblast samples (Figure 1). Non-T2DM iLTS fibroblasts were less clustered and more metabolically heterogeneous, most notably in sample S5. Sample-to-sample comparison via a Pearson R coefficient heat map showed that T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblast cell lines were metabolically correlated and that non-T2DM iLTS fibroblasts were more heterogenous (Figure 2a). A 2-component partial least squares discriminant analysis (Q2 = −0.74, R2 = 0.86) demonstrated 2 distinct groups metabolically as a function of etiology (T2DM vs non-T2DM; Figure 2b).

Figure 1.

Heat map of samples vs metabolites. Pearson R coefficient heat map of fibroblast samples vs metabolites detected by mass spectrometry. Normal, red; non-T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts, green; T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts, blue. Color scale range: −3 (blue) to +3 (red). iLTS, iatrogenic laryngotracheal stenosis; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 2.

Clustering of iLTS-scar fibroblasts. (A) Intersample Pearson R coefficient heat map with strong correlations between T2DM iLTS-scar samples (box with white border). (B) Partial least squares discriminant analysis scoring chart shows nonrandom clustering representing distinct metabolic profiles. Shaded areas = 95% confidence regions. iLTS, iatrogenic laryngotracheal stenosis; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Mitochondria-Related Metabolites Are Elevated in T2DM iLTS-Scar Fibroblast

Data were collected on a total of 71 metabolites, with 8 peaks (1.9%) excluded from subsequent analysis due to an insufficient signal-to-noise ratio. Metabolic discovery (Figure 3) revealed that 1 metabolite, itaconate, was elevated in T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts (2.0×, P = .045). Two additional metabolites, riboflavin and pyridoxine, trended toward an increase (9.5×, P = .125; 1.6×, P = .056, respectively) in T2DM iLTS-scar. Acetylcarnitine (0.061, P = .007) and 2-aminooctanic acid (0.22×, P = .008) were significantly decreased in T2DM iLTS-scar as compared with non-T2DM iLTS-scar. Metabolites in the glutamine pathway (glutamate and hydroxyproline) were elevated (21× and 17×) in non-T2DM iLTS fibroblasts, although these did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 3.

Metabolic discovery. Volcano plot between non-T2DM (green/left) and T2DM (right/blue) iLTS-scar fibroblasts. Values represents an individual metabolite and expression in T2DM vs non-T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblast samples. Itaconate (2.0×; P = .045) was elevated in T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts. iLTS, iatrogenic laryngotracheal stenosis; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

FAP+ CD90+ Subsets Are Predominant in T2DM iLTS-Scar Fibroblasts

Figure 4a shows the gating strategy. The fibroblast marker FAP (>98% expression) was used for subsequent gating of cells (Figure 4b). T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts (n = 3) had a significantly higher expression of FAP+CD90+ cells (mean expression, 95%; P = .004) as compared with non-T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts (n = 3, mean = 83.6%, P = .0109) or controls (n = 3, mean = 81.1%, P = .0042). There was no difference between non-T2DM iLTS-scar and normal tracheal fibroblasts. FAP+PDGFR+ fibroblasts were less common (<5% expression) in all groups except for a T2DM iLTS-scar sample, which was slightly elevated at 11%. Less than 20% of fibroblasts expressed FAP+CD34+ and were not significantly different among the control, T2DM, and non-T2DM iLTS-scar groups. Less than 1% of living cells expressed CD31 (PECAM).

Figure 4.

High-CD90 expression in T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts. (A) Fibroblast flow gating schema. A, area; FSC, forward scatter; H, height; SSC, side scatter. (B) FAP+CD90+ fibroblasts were more prevalent in T2DM than in non-T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts (P = .011) and control (P = .0042). *P <.05. **P <.01. CD90, Thy-1; FAP, fibroblast activation protein; iLTS, iatrogenic laryngotracheal stenosis; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the metabolomics of T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts. T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts represent a metabolically homogenous population and are distinguishable from non-T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts in a number of metabolic pathways, including elevated itaconate. T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts could be identified by increased CD90 (Thy-1) expression as compared with non-T2DM iLTS-scar and nonscar fibroblasts. Together, these data demonstrate that cultured T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts express an etiology-specific metabolic profile that can be identified by extracellular marker phenotyping.

Although in its infancy, metabolomics has become a powerful tool for identifying metabolite substrate changes on a cellular level.29 In our study, we found clinically distinct patients with T2DM and iLTS to have scar fibroblasts that are characterized by a unique metabolic profile. Similar metabolic profiles were recently noted in dermal scar and thought to affect progenitor fibroblasts resulting in excessive scaring.10 However, correlating these metabolites to biologic pathways is difficult as few have reported on metabolite function in fibrosis. For instance, acetylcarnitine and 2-aminoctonic acid are involved with fatty acid synthesis, but neither has been studied in fibroblasts.30 Despite these challenges, we found that T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts have higher expression of itaconate when compared with non-T2DM iLTS. As a metabolic by-product of the citric acid cycle, itaconate is highly activated after inflammation and reduces collagen production in fibroblasts derived from patients with systemic sclerosis in vitro.31,32 As a biomarker, itaconate is correlated with disease severity in models of rheumatoid arthritis and is reduced with immunomodulatory treatment.33 Riboflavin (vitamin B2) and pyridoxine (vitamin B6), 2 metabolites heavily involved with mitochondrial metabolism, also trended toward increased expression in T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts.34,35 However, non-T2DM iLTS fibroblasts had an increased trend in levels of glutamate and hydroxyproline, 2 key components of glutamine metabolism that have been leveraged for inhibiting non-T2DM iLTS fibroblasts, which are more dependent on Warburg-like physiology (aerobic glycolysis).4,21 The metabolic profile of T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts in this study identifies specific substrates that are consistently elevated in the cell lines studied here.

To characterize the fibroblasts within the metabolically homogenous T2DM iLTS-scar, we evaluated for fibroblast-associated cell markers in the T2DM iLTS fibroblast cell lines. First, the purity of the cells lines was confirmed by finding that 98% of cells expressed FAP, with minimal CD31 (PECAM) staining for endothelial cells. While all samples expressed CD90, T2DM iLTS-scar had the highest expression versus non-T2DM or control iLTS-scar fibroblasts. In a study of 117 patients with keloid or hypertrophic scaring, Ho et al found similar pathologic CD90+ fibroblasts, which were derived from a CD34-to-CD90 fibroblast transition and histologically correlated with worsening scar progression.36 In other studies, fibroblasts expressing CD90 that were derived from arthritic joints in a murine model were proinflammatory and destructive when adoptively transferred into naïve joints, characteristic of an “activated” fibroblast subset.17 The activated CD90+ fibroblast subset in our study is predominant with T2DM iLTS-scar and may propagate the fibrotic phenotype.

While our study successfully characterized a metabolically distinct fibroblast subset in T2DM iLTS-scar, there are several limitations. The use of growth media, for instance, likely affects metabolic processes by providing a surplus of amino acids and growth factors for replication. Although cell starving is sometimes proposed to reduce the effects of growth media, cells that are dependent on aerobic (mitochondrial) metabolism are more sensitive to starvation than other subsets and therefore this method was not utilized as it could skew our results.37 Moreover, the non-T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts in our study were more heterogenous (Figure 1), which may be secondary to the presence of additional fibroblast subsets within the non-T2DM iLTS-scar group. Cultured fibroblasts are also known to undergo morphological changes and partial differentiation into myofibroblast-like phenotypes under normal culture conditions after plating.38,39 To limit the impact of dedifferentiation on identifying key fibroblast subsets in vitro, we used cells of low passage (≤2), which maintain greater similarity to primary cells. This subsequently reduced our sample availability and resulted in different control groups for the 2 experiments: tracheal biopsies from patients with iLTS in mass spectrometry and normal trachea from rapid autopsy specimens in flow cytometry experiments. Although we found a significant difference between CD90+ expression in T2DM and non-T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts, the clinical impact of CD90+ fibroblast subsets is still unknown. Future studies utilizing primary cells derived from dissociated tissue biopsy samples (prior to culture-induced changes) may better reflect laryngotracheal stenosis disease in vivo.

Conclusions

Clinically, patients with T2DM are at increased risk of developing iLTS. Distinct metabolic profiles exist within T2DM iLTS and are likely linked to clinical phenotype. In this study, we discovered a metabolically distinct phenotype in T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts that is correlated with elevated levels of itaconate. These T2DM iLTS-scar fibroblasts can be identified by increased expression of the extracellular marker CD90 (Thy-1) and represent an activated subset that may perpetuate fibrosis.

Supplementary Material

Funding source:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders of the National Institutes of Health under awards 1R01DC018567, R21DC017225, and T32DC000027. This study was also financially supported by the Triological Society and American College of Surgeons (Alexander T. Hillel) and the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation Resident Research Grant (Ioan A. Lina).

Footnotes

Competing interests: Alexander T. Hillel has a sponsored research agreement with Medtronic to investigate tracheostomy tube injury to the trachea.

Sponsorships: None

Supplemental Material

Additional supporting information is available in the online version of the article.

This article was presented at the AAO-HNSF 2020 Virtual Annual Meeting & OTO Experience; September 13–October 25, 2020.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Sempowski GD, Beckmann MP, Derdak S, Phipps RP. Subsets of murine lung fibroblasts express. Published 2019. Accessed September 30, 2019. http://www.jimmunol.org/content/152/7/3606 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelbard A, Francis DO, Sandulache VC, Simmons JC, Donovan DT, Ongkasuwan J. Causes and consequences of adult laryngotracheal stenosis. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(5):1137–1143. doi: 10.1002/lary.24956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gadkaree SK, Pandian V, Best S, et al. Laryngotracheal stenosis: risk factors for tracheostomy dependence and dilation interval. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(2):321–328. doi: 10.1177/0194599816675323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma G, Samad I, Motz K, et al. Metabolic variations in normal and fibrotic human laryngotracheal-derived fibroblasts: a Warburg-like effect. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(3):E107–E113. doi: 10.1002/lary.26254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gadkaree SK, Pandian V, Best S, et al. Laryngotracheal stenosis: risk factors for tracheostomy dependence and dilation interval. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2017;156(2):321–328. doi: 10.1177/0194599816675323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillel AT, Karatayli-Ozgursoy S, Samad I, et al. Predictors of posterior glottic stenosis: a multi-institutional case-control study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125(3):257–263. doi: 10.1177/0003489415608867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shinn JR, Kimura KS, Campbell BR, et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute laryngeal injury after prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(12):1699–1706. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lina I, Tsai H, Ding D, Davis R, Motz KM, Hillel AT. Characterization of fibroblasts in iatrogenic laryngotracheal stenosis and type II diabetes mellitus. Laryngoscope. Published online August 28, 2020. doi: 10.1002/lary.29026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;138:271–281. doi: 10.1016/J.DIABRES.2018.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song J, Li X, Li J. Emerging evidence for the roles of peptide in hypertrophic scar. Life Sci. 2020;241:117174. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.117174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Para R, Romero F, George G, Summer R. Metabolic reprogramming as a driver of fibroblast activation in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Med Sci. 2019;357(5):394–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang YP, Lee SB, Lee JM, et al. Metabolic profiling regarding pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Proteome Res. 2016;15(5):1717–1724. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reichard A, Wanner N, Stuehr E, et al. Quantification of airway fibrosis in asthma by flow cytometry. Cytom Part A. 2018;93(9): 952–958. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.23373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizoguchi F, Slowikowski K, Wei K, et al. Functionally distinct disease-associated fibroblast subsets in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):789. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02892-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rinkevich Y, Walmsley GG, Hu MS, et al. Skin fibrosis: identification and isolation of a dermal lineage with intrinsic fibrogenic potential. Science. 2015;348(6232):2151. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa2151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fowlkes V, Clark J, Fix C, et al. Type II diabetes promotes a myofibroblast phenotype in cardiac fibroblasts. Life Sci. 2013; 92(11):669–676. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Croft AP, Campos J, Jansen K, et al. Distinct fibroblast subsets drive inflammation and damage in arthritis. Nature. 2019; 570(7760):246–251. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1263-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varasteh Z, Mohanta S, Robu S, et al. Molecular imaging of fibroblast activity after myocardial infarction using a 68Ga-labeled fibroblast activation protein inhibitor, FAPI-04. J Nucl Med. 2019;60(12):1743–1749. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.119.226993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H, Fitchett C, Kozdon K, et al. Independent adipogenic and contractile properties of fibroblasts in Graves’ orbitopathy: an in vitro model for the evaluation of treatments. PLoS One. 2014; 9(4):e95586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Díaz-Flores L, Gutiérrez R, García MP, et al. Human resident CD341 stromal cells/telocytes have progenitor capacity and are a source of αSMA+ cells during repair. Histol Histopathol. 2015;30(5):615–627. doi: 10.14670/HH-30.615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsai HW, Motz KM, Ding D, et al. Inhibition of glutaminase to reverse fibrosis in iatrogenic laryngotracheal stenosis. Laryngoscope. Published online January 6, 2020. doi: 10.1002/lary.28493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motz K, Samad I, Yin LX, et al. Interferon-γ treatment of human laryngotracheal stenosis–derived fibroblasts. JAMA Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2017;143(11):1134. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.0977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis RJ, Lina I, Ding D, et al. Increased expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 in patients with laryngotracheal stenosis. Laryngoscope. Published online June 17, 2020. doi: 10.1002/lary.28790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chornoguz O, Hagan RS, Haile A, et al. mTORC1 promotes T-bet phosphorylation to regulate Th1 differentiation. J Immunol. 2017;198(10):3939–3948. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chong J, Xia J. Using MetaboAnalyst 4.0 for metabolomics data analysis, interpretation, and integration with other omics data. In: Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol 2104. Humana Press Inc; 2020:337–360. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0239-3_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia J, Psychogios N, Young N, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst: a web server for metabolomic data analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(suppl 2):W652–W660. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noble JE, Knight AE, Reason AJ, Di Matola A, Bailey MJA. A comparison of protein quantitation assays for biopharmaceutical applications. Mol Biotechnol. 2007;37(2):99–111. doi: 10.1007/s12033-007-0038-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szymańska E, Saccenti E, Smilde AK, Westerhuis JA. Double-check: validation of diagnostic statistics for PLS-DA models in metabolomics studies. Metabolomics. 2012;8(S1):3–16. doi: 10.1007/s11306-011-0330-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang C, Chen L, Rabinowitz JD. Metabolomics and isotope tracing. Cell. 2018;173(4):822–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adeva-Andany MM, Calvo-Castro I, Fernández-Fernández C, Donapetry-García C, Pedre-Piñeiro AM. Significance of l-carnitine for human health. IUBMB Life. 2017;69(8):578–594. doi: 10.1002/iub.1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lampropoulou V, Sergushichev A, Bambouskova M, et al. Itaconate links inhibition of succinate dehydrogenase with macrophage metabolic remodeling and regulation of inflammation. Cell Metab. 2016;24(1):158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henderson J, Duffy L, Stratton R, Ford D, O’Reilly S. Metabolic reprogramming of glycolysis and glutamine metabolism are key events in myofibroblast transition in systemic sclerosis pathogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. Published online November 2, 2020. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.16013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michopoulos F, Karagianni N, Whalley NM, et al. Targeted metabolic profiling of the Tg197 mouse model reveals itaconic acid as a marker of rheumatoid arthritis. J Proteome Res. 2016; 15(12):4579–4590. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scholte HR, Busch HFM, Bakker HD, Bogaard JM, Luyt-Houwen IEM, Kuyt LP. Riboflavin-responsive complex I deficiency. BBA Mol Basis Dis. 1995;1271(1):75–83. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(95)00013-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dalto D, Matte J-J. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) and the glutathione peroxidase system: a link between one-carbon metabolism and antioxidation. Nutrients. 2017;9(3):189. doi: 10.3390/nu9030189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho JD, Chung HJ, Barron A, et al. Extensive CD34-to-CD90 fibroblast transition defines regions of cutaneous reparative, hypertrophic, and keloidal scarring. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019; 41(1):16–28. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000001254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan HWS, Sim AYL, Long YC. Glutamine metabolism regulates autophagy-dependent mTORC1 reactivation during amino acid starvation. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):338. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00369-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang YHK, Ogando CR, Wang See C, Chang TY, Barabino GA. Changes in phenotype and differentiation potential of human mesenchymal stem cells aging in vitro. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0876-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baranyi U, Winter B, Gugerell A, et al. Primary human fibroblasts in culture switch to a myofibroblast-like phenotype independently of TGF beta. Cells. 2019;8(7):721. doi: 10.3390/cells8070721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.