Summary

T cell activation requires the processing and presentation of antigenic peptides in the context of a major histocompatibility complex (MHC complex). Cross-dressing is a non-conventional antigen presentation mechanism, involving the transfer of preformed peptide/MHC complexes from whole cells, such as apoptotic cells (ACs) to the cell membrane of professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells (DCs). This is an essential mechanism for the induction of immune response against viral antigens, tumors, and graft rejection, which until now has not been clarified. Here we show for first time that the P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) is crucial to induce cross-dressing between ACs and Bone-Marrow DCs (BMDCs). In controlled ex vivo assays, we found that the P2X7R in both ACs and BMDCs is required to induce membrane and fully functional peptide/MHC complex transfer to BMDCs. These findings show that acquisition of ACs-derived preformed antigen/MHC-I complexes by BMDCs requires P2X7R expression.

Subject areas: Cell biology, Immune response, Immune system

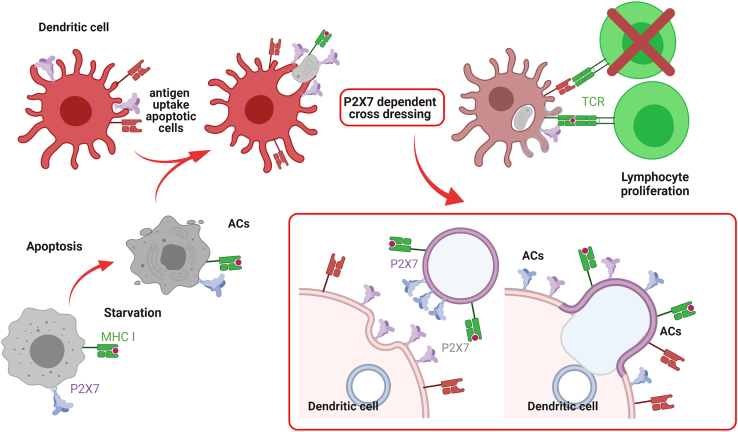

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Cross-dressing of antigens to Dendritic Cells (DCs) is dependent of P2X7 receptor

-

•

The P2X7 receptor must be present in both Dendritic Cells and antigen source

-

•

The transfer of antigen/MHC-I complexes to DCs is functional and activates T CD8 cells

-

•

The P2X7 receptor allows Cross-Dressing possibly through a membrane fusion process

Cell biology; Immune response; Immune system

Introduction

The P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) is a highly polymorphic member of the P2X family of ATP-gated cation-selective ion channels, but, at variance with the other members of the P2X family, this receptor can also form non-selective plasma membrane pores that are permeable to hydrophilic molecules of MW up to 900Da. P2X7R activation is linked to the stimulation of key immune-related responses such as activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1β maturation and release, initiation of various intracellular signaling cascades, scavenging of apoptotic cells, induction of cell-cell fusion, and therefore of multinucleated giant cell formation in vitro (Di Virgilio et al., 2017; Savio et al., 2018). The P2X7R is widely expressed in hematopoietic cells, including T cells and antigen-presenting cells (APC), such as dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages, where it is hypothesized to play a key role in differentiation and antigen (Ag) presentation (Borges Da Silva et al., 2018; Mutini et al., 1999; Rivas-Yáñez et al., 2020).

In DCs, besides NLRP3 inflammasome activation and presentation of soluble extracellular Ags, the P2X7R has been associated to additional responses such as microvesicle-mediated tissue factor release (Baroni et al., 2007), DC migration in response to endogenous danger signals (Sáez et al., 2017), and up-regulation of tolerogenic factors (Lecciso et al., 2017). Owing to its participation in Ag presentation and its fusogenic activity, we hypothesized that the P2X7R might be also involved in non-canonical mechanisms of Ag presentation of exogenous proteins (Nakayama, 2014). One such mechanism is cross-dressing, which involves the transfer of preformed peptide/MHC complexes from various antigenic sources, such as whole live/dead cells or his derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) to the plasma membrane of DCs, thus bypassing canonical Ag processing and resulting in a rapid activation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (Dolan et al., 2006; Mohapatra et al., 2020; Nakayama, 2014). This mechanism, possibly requiring membrane fusion between donor cell and recipient DCs, has been implicated in several physiological and physio-pathological processes, including the induction of immune response against viruses and tumors, and graft rejection (Zeng and Morelli, 2018). Cross-dressed cells can present the intact, unprocessed, peptide-MHC complexes to T lymphocytes and have a crucial role in activating memory, but not naive T cells (Wakim and Bevan, 2011). Here we identified a new P2X7R-dependent mechanism of cross-dressing, where the purinergic P2X7R expression is mandatory to promote membrane and peptide/MHC complex transfer from apoptotic cells (ACs) to DCs. In controlled ex vivo assays, we found that P2X7-mediated peptide/MHC transfer is fully functional and induces antigen-dependent T cell activation.

Results

The P2X7 receptor supports membrane transfer from apoptotic cells (ACs) to dendritic cells (DCs)

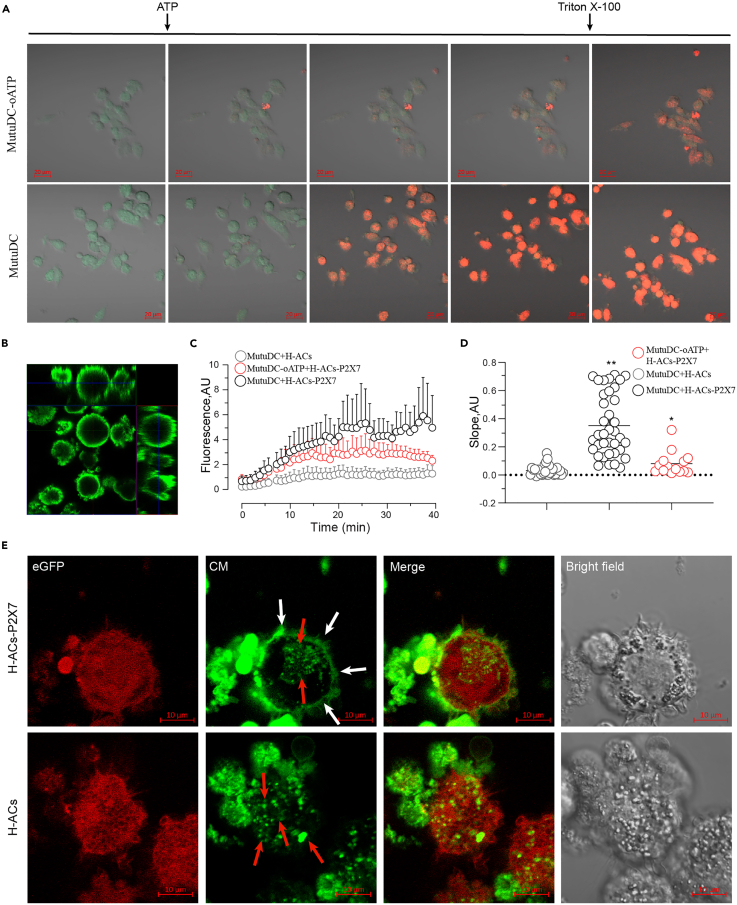

To assess participation of P2X7 in cross-dressing, we first verified whether the receptor (P2X7R) was expressed on the cell membranes of P2X7R-transfected HEK293 cells (donor) and in Mutu1940 DC line (MutuDC) (acceptor). We evaluated P2X7R activity by ethidium bromide (EtBr) incorporation with a time-lapse assay. Cells were incubated with EtBr and stimulated with 1mM ATP in the presence or absence of oxidized ATP (oATP), a weakly selective but very effective and widely used P2X7R antagonist (Murgia et al., 1993), then Triton X-100 addition was used to evaluate total EtBr incorporation. Representative images of MutuDC challenged with ATP alone show that EtBr was incorporated into the cells, and this process was inhibited by the P2X7R antagonist (Figures 1A and S1A). A similar ATP-induced EtBr uptake was observed in P2X7R-expressing but not in Wild Type (WT) HEK293 cells (Figure S1A), in agreement with previous reports (Leiva-Salcedo et al., 2011). These results confirm the presence of a functional P2X7R in MutuDCs and P2X7R-transfected HEK293 cells.

Figure 1.

H-ACs-P2X7 favor the membrane transfer to Mutu dendritic cells

(A). The expression of P2X7R in MutuDCs was evaluated in a functional assay as Ethidium Bromide (20 μg/mL) uptake over time in response to ATP (1 mM). Representative micrographs (every 5 min) are shown; ATP and Triton X-100 addition are indicated. Scale bar 20 µm.

(B) To evaluate the membrane transfer, ACs generated from transfected or parental HEK293 were labeled with the lipophilic stain CM Deep Red , shown as green pseudocolor. Orthogonal projection obtained from Z-stacks denotes the fluorescent membrane.

(C) MutuDCs were challenged with CM-labeled ACs. Transfer of fluorescence was evaluated in a circular region of interest on the outer perimeter of selected cells. The fluorescence over time was plotted for ACs loaded with CM using the ZEN Blue edition 2.6 software. Three to nine independent experiments were performed quantifying from 3 to 8 cells each one. The graph shows the fluorescence quantification on MutuDC1940 surface incubated with H-ACs-P2X7 (black), MutuDCs pretreated with oATP (300μM), and incubated with H-ACs-P2X7 (red) and MutuDCs incubated with parental H-ACs (gray).

(D) Slopes calculated from the fluorescence quantification curves shown in (C) Data are represented as the mean ± SEM. Results were analyzed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney test.

(E) Ninety minutes after the challenge with H-ACs-P2X7 or H-ACs, cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy. Representative micrographs show MutuDCs expressing eGFP, CM labeled H-ACs and the superposition of both colors. A peripheral (white arrows) and vesiculated (red arrows) distribution pattern are indicated. Scale bar 10 µm. ∗∗ and ∗ represent p < 0.01 and p < 0.05 respectively.

The first studies of cross-dressing used apoptotic cells as an antigenic sources model (Dolan et al., 2006). Consequently, in our previous report (Morales et al., 2017), we used a starvation protocol to induce apoptosis in WT HEK293 cells or P2X7R-expressing HEK293. These Apoptotic Cells (ACs) showed >94% of apoptotic markers and 200 μm2 in diameter (Barrera-Avalos et al., 2021). The ACs generated (here referred to as H-ACs or H-ACs P2X7, respectively) were used as membrane donors. Then, ACs were stained with CellMask Green Plasma Membrane Stain (CM) and the fluorescence distribution on ACs was evaluated by orthogonal reconstruction using confocal microscopy. As expected, CM stains the membrane zone, but not the lumen in both H-ACs and H-ACs-P2X7 as showed in the representative orthogonal reconstruction of the confocal images for H-ACs-P2X7 (Figure 1B), although electron microscopy is necessary for its full confirmation. MutuDCs were then challenged with freshly CM-labeled ACs, and the time course of CM transfer was evaluated by measuring fluorescence increases in defined regions of interest (ROI) on the surface of MutuDC, which probably corresponds mostly to plasma membranes. We analyzed a membrane-containing zone of the cell and found a time-dependent increase of CM fluorescence in MutuDCs challenged with CM H-ACs-P2X7. This increased fluorescence was largely inhibited by oATP (Figure 1C) and was not observed in MutuDCs challenged with CM H-ACs (Figure 1C). The time-lapse experiments showed that fluorescence intensity on the MutuDC plasma membrane zone peaked about 20 min after ACs supplementation, with an increase in the ascending slope of CM H-ACs-P2X7 that was partially inhibited by oATP-pretreatment in MutuDCs (Figure 1D). Although the localization of CM on MutuDCs plasma membrane challenged from CM H-ACs-P2X7 should be verified by an ultrastructural analysis, our images showing CM preferentially staining the periphery of MutuDCs (white arrows) suggest that it corresponds to cell plasma membrane, while is detected to a lesser extent in a vesicular pattern (red arrows) (Figure 1E). Orthogonal reconstruction of the confocal images confirms that CM was at the cell surface edge (Figure S2A). On the time-lapse video, CM is observed on the membrane protrusions generated by the MutuDCs engulfing ACs (Video S1). Finally, Fluorescence Recovery After Photo bleaching (FRAP) analysis showed that the CM intensity was partially restored in the membrane plasmatic zone within the bleached area to about 61 ± 5% in a median recovery time of 4.6 ± 1.5 s (Figure S3). Besides, in absence of the P2X7R, CM shows only a vesicular pattern with no evident transfer to the DC plasma membrane or cell surface (Figure 1E, red arrows), as also shown by the 2D orthogonal reconstruction (Figure S2B). The time-lapse video shows that pieces of CM H-ACs-P2X7, but not of CM H-ACs, were detached and incorporated into the surface of DCs, most likely in the plasma membrane (Video S2). All these data indicate that P2X7R expression on ACs is necessary for a possible membrane transfer to DCs, although electron microscopy is necessary for its full confirmation. MutuDCs were then challenged with freshly CM-labeled ACs, and the time course of CM transfer was evaluated by measuring fluorescence increase in defined regions of interest (ROI) on the surface of MutuDC, which probably corresponds mostly to plasma membranes. We analyzed a membrane-containing zone of the cell and found a time-dependent increase of CM fluorescence in MutuDCs challenged with CM H-ACs-P2X7. This increased fluorescence was largely inhibited by oATP (Figure 1C) and was not observed in MutuDCs challenged with CM H-ACs (Figure 1C). The time-lapse experiments showed that fluorescence intensity on the MutuDC plasma membrane zone peaked about 20 min after ACs supplementation, with an increase in the ascending slope of CM H-ACs-P2X7 that was partially inhibited by oATP-pretreatment in MutuDCs (Figure 1D). Although the localization of CM on MutuDCs plasma membrane challenged from CM H-ACs-P2X7 should be verified by an ultrastructural analysis, our images showing CM preferentially staining the periphery of MutuDCs (white arrows) suggest that it corresponds to cell plasma membrane, while is detected to a lesser extent in a vesicular pattern (red arrows) (Figure 1E). Orthogonal reconstruction of the confocal images confirms that CM was at the cell surface edge (Figure S2A). On the time-lapse video, CM is observed on the membrane protrusions generated by the MutuDCs engulfing ACs (Video S1). Finally, Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) analysis showed that the CM intensity was partially restored in the membrane plasmatic zone within the bleached area to about 61 ± 5% in a median recovery time of 4.6 ± 1.5 s (Figure S3). Besides, in absence of the P2X7R, CM shows only a vesicular pattern with no evident transfer to the DC plasma membrane or cell surface (Figure 1E, red arrows), as also shown by the 2D orthogonal reconstruction (Figure S2B). The time-lapse video shows that pieces of CM H-ACs-P2X7, but not of CM H-ACs, were detached and incorporated into the surface of DCs, most likely in the plasma membrane (Video S2). All these data indicate that P2X7R expression on ACs is necessary for a possible membrane transfer to DCs.

Membrane transfer from P2X7 H-ACs to Mutu1940 dendritic cells. Mutu1940 dendritic cells expressing eGFP (red pseudocolor) and H-ACs-P2X7 labeled on their membrane with the lipophilic marker CellMask (CM) DeepRed (green pseudocolor). The size scale is displayed at the bottom of the video and the elapsed minutes are displayed at the top right. Representative of 3 independent experiments.

Membrane transfer from parental H-ACs to Mutu dendritic cells. MutuDCs expressing eGFP (red pseudocolor) and H-ACs-P2X7 labeled the CellMask (CM) DeepRed membrane marker (green pseudocolor). The size scale is displayed at the bottom of the video and the elapsed minutes are displayed at the top right. Representative of 4 independent experiments.

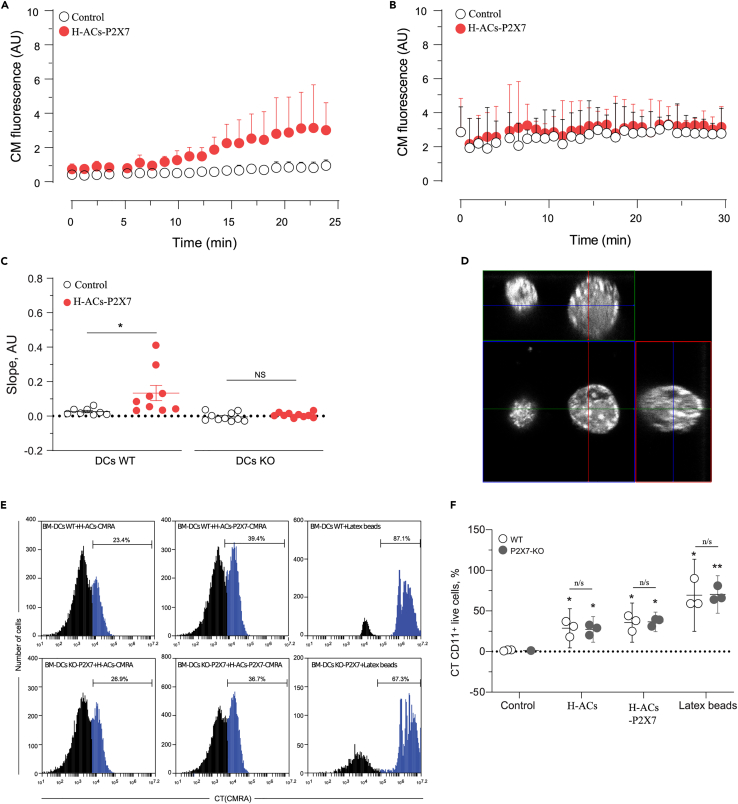

To verify whether presence of the P2X7R on the acceptor DCs is also required for membrane transfer from ACs, bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) from WT-C57BL/6 (B6) or C57BL/6 P2X7-KO mice were challenged with CM H-ACs-P2X7 or CM H-ACs. In contrast to MutuDCs, BMDCs are highly mobile, making it difficult to perform ROI analysis. Despite this, time-lapse experiments showed that CM from CM H-ACs-P2X7 was readily transferred to the plasma membrane zone of WT-BMDCs (Figure 2A). On the contrary, CM from H-ACs-P2X7 was not transferred to the plasma membrane zone of P2X7-KO-BMDCs (Figure 2B). No membrane fluorescence by CM was found in BMDCs not contacting ACs. Accordingly, slopes of fluorescence increase in time-lapse experiments showed an increase only in WT but not in P2X7-KO-BMDCs incubated with H-ACs-P2X7. Furthermore, no fluorescence increase was detected in WT- or P2X7-KO-BMDCs non-associated to ACs (Figure 2C). To rule out that lack of CM transfer to P2X7R-deficient cells was due to decreased phagocytosis, we analyzed ACs-phagocytosis in WT-BMDCs and P2X7-KO-BMDCs. ACs was generated from HEK293 cells stained with Cell tracker fluorescent probe (CT), and phagocytosis was measured by flow cytometry in CT+ BMDCs (CD11c+ cells) excluding propidium iodide positive (PI+) cells to discard ACs associated to non-phagocytosing BMDCs. H-ACs show whole-cell fluorescence distribution in the 2D orthogonal reconstruction from data obtained by confocal microscopy (Figure 2D). Similar phagocytosis levels were observed in WT and P2X7-KO-BMDCs, regardless of the presence of P2X7R in the H-ACs (Figures 2E and 2F). This observation supports the conclusion that increased incorporation of membrane markers into DC plasma membranes is not due to differential phagocytosis of P2XR-expressing versus P2X7R-less ACs. Altogether these data indicate that the P2X7R is essential for a possible membrane transfer from ACs to BMDCs.

Figure 2.

P2X7 in DCs favor the membrane transfer from ACs to MutuDC cells

(A and B) CellMask transference from H-ACs to the surface of the BM-DCs (A) and P2X7-KO BM-DCs (B) was analyzed to assess the role of DC P2X7 in membrane transference. Graphs show the fluorescence intensity on the surface of BM-DCs associated with ACs (red) and BM-DCs not associated with ACs (control, open black).

(C) Graph shows the slope derived from each fluorescence intensity curve.

(D) P2X7 expressing or parental HEK293 cells were loaded with CellTracker Orange (CMRA), and H-ACs were obtained by nutrient deprivation. The orthogonal projection of H-ACs shows the whole-cell distribution of fluorescence. ACs are shown as white pseudocolor.

(E and F) Representative histograms and (F) percentage of BM-DCs which have phagocytosed CMRA labeled ACs. H-ACs and H-ACs-P2X7 phagocytosed by CD11c+ 7-AAD+ WT DCs (Upper panel) or CD11c+ 7-AAD+ P2X7-KO DCs (Lower panel). Phagocytosis of fluorescence latex beads was the positive control. The quantification of three independent experiments was graphed and represented as the mean ± SEM. Results were analyzed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney test, ∗ represent significant differences p < 0.05 and ∗∗ p < 0.01, treatments compared against control, n/s; not significant.

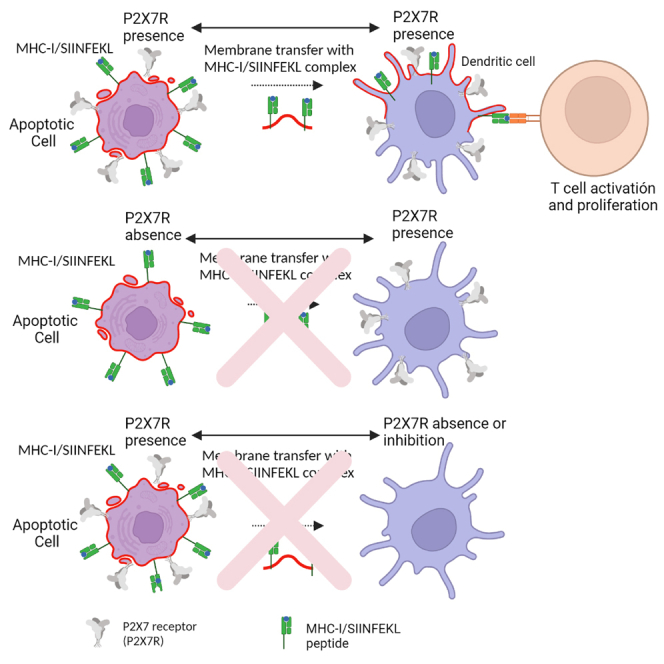

P2X7 receptor mediates a functional peptide/MHC-I complex from apoptotic cells to dendritic cells

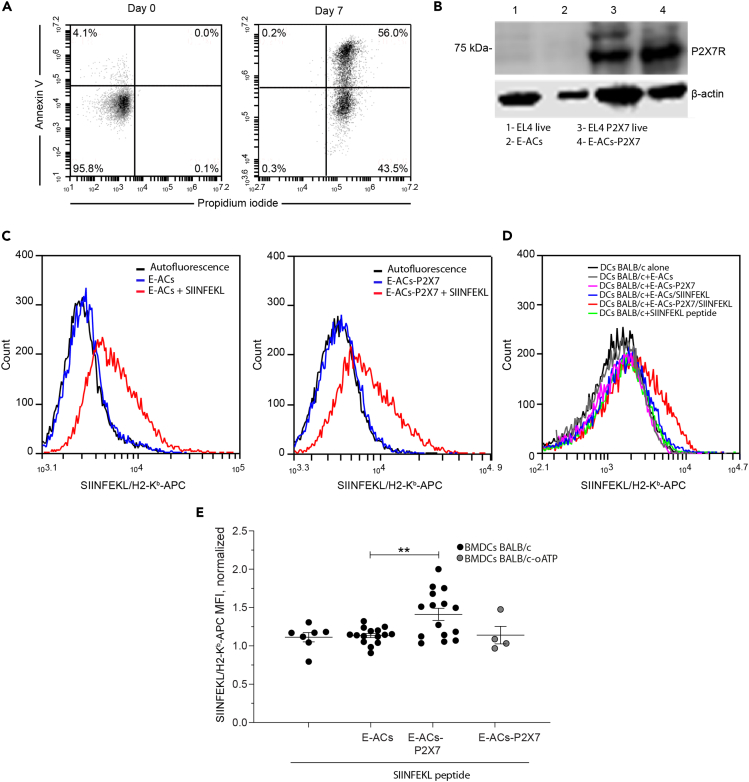

The next step was to determine whether the P2X7R facilitates cross-dressing. First, we generated ACs from WT EL4 (E-ACs) and EL4 cells P2X7R-expressing (E-ACs-P2X7) both with H-2b haplotype (Figure 3A) and evaluated the transfer of the ovalbumin-derived SIINFEKL/H-2Kb complex from ACs to BMDCs generated from BALB/cJ mice (H-2d haplotype). P2X7 expression was detected by Western blot in P2X7R-transfected EL4 and ACs thereof, but slightly in the parental cells (Figure 3B). WT-EL4 and P2X7R-transfected EL4 cells expressed high levels of MHC-I, and were loaded to same level with the SIINFEKL peptide, thus indicating that the P2X7R transfection process did not interfere with peptide loading (Figure 3C left and right histograms). Following incubation of the allogeneic H-2d BMDCs with SIINFEKL-loaded E-CAs or SIINFEKL-loaded P2X7R-E-CAs, expression of the peptide/H-2Kb complex cell surface was analyzed by flow cytometry on the H-2d BMDCs, as explained in the representative methodological scheme (Figure S4). Interestingly, transfer of SIINFEKL/H-2Kb to BMDCs occurred only from SIINFEKL-loaded P2X7-E-ACs (E-ACs-P2X7/SIINFEKL) but not from SIINFEKL-loaded E-ACs (E-ACs/SIINFEKL) (Figure 3D). Furthermore, the inhibition of P2X7 by oATP in BMDCs BALB/c interferes in the transfer of the SIINFEKL/MHC-I complex even using E-ACs-P2X7/SIINFEKL (Figure 3E). BMDCs-BALB/c (H-2d) incubated with ACs alone and soluble SIINFEKL peptide, does not generate an increase in SIINFEKL/MHC-I (Figure 3D). The quantitative expression of all added controls is shown in Figure S5. These results demonstrated that the P2X7R is required on both sides (DCs and antigen source) for the cross-dressing of BMDCs with peptide/MHC I complex derived from ACs.

Figure 3.

CD8+ OT-1 lymphocytes are activated by P2X7-dependent cross-dressing

(A) ACs generated from EL4 cells (E-ACs) by nutrient deprivation-induced cell death were identified with Annexin V (AV) and Propidium Iodide (PI) on the seventh day of culture. Representative dot plots of flow cytometry analysis show two populations of E-ACs: late Apoptotic (PI + AV+) and early apoptotic (PI-AV+) E-ACs. Data represents one of three independent experiments. Only PI-AV- cells are present at the beginning of treatment.

(B) Western blot for P2X7 receptor from EL4 live cells, E-ACs, EL4 P2X7 live cells, and E-ACs-P2X7, 1–4 lanes, left to right, respectively. The 75 kDa band corresponds to the molecular weight of the P2X7 receptor.

(C) The SIINFEKL/H2-Kb presence was evaluated by flow cytometry in ACs generated from both parental (E-ACs, left side) and P2X7 overexpressing (E-ACs-P2X7, right side) H-2Kb EL4 cells. SIINFEKL/H2-Kb in unloaded ACs (blue) and peptide-loaded ACs (red) were compared against basal fluorescence (no antibody, black).

(D) Evaluation of antigen/MHC (SIINFEKL/H2-Kb complex) transference from ACs to the surface of allogenic (H-2d) BMDCs-BALB/c. A representative histogram from 15 independent experiments of the SIINFEKL/H2-Kb detected in CD11+ BM-DCs challenged with E-ACs (gray), E-ACs-P2X7 (pink), E-ACs SIINFEKL (blue), and E-ACs-P2X7/SIINFEKL (red). As controls, BMDCs-BALB/c not challenged (black) and challenged with SIINFEKL peptide (green) were included.

(E) The quantification of at least six independent experiments was graphed and represented as the mean ± SEM, SIINFEKL/H2-Kb MFI in CD11+ BM-DCs normalized to DCs not challenged. Gray circles represent BMDCs-BALB/c pretreated with oATP before challenge with each treatment. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Results were analyzed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney test, ∗∗ p < 0.01.

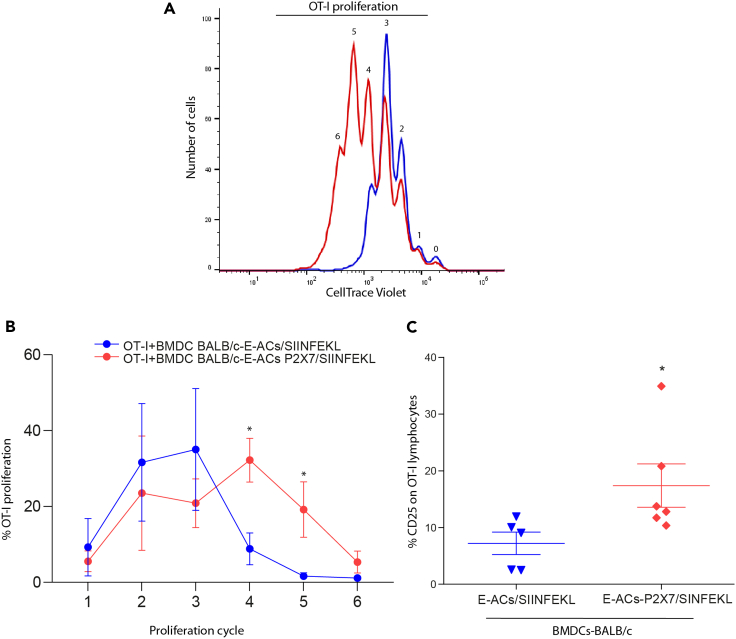

To determine whether the transferred peptide/MHC complexes to BMDC-BALB/c were functional, i.e., capable of activating specific T CD8+ cells, BMDCs-BALB/c challenged for 24 h with E-ACs and E-ACs-P2X7, with or without SIINFEKL, were co-cultured with CellTrace-labeled OT-I CD8+ T cells, responsive to SIINFEKL/MHC-I complex (in H-2b context, same haplotype as EL4 cells). OT-I lymphocytes incubated with BMDC-BALB/c loaded with the SIINFEKL/MHC-I complex from E-ACs expressing P2X7R (E-ACs-P2X7/SIINFEKL), showed six marked rounds of proliferation compared to BMDC-BALB/c charged with ACs/SIINFEKL without P2X7 (Figure 4A). Furthermore, this was related to a higher percentage of OT-I cells in higher proliferation cycles (Cycle 4–5) for the first condition compared to the second (Cycles 2–3) (Figure 4B, Red lines). OT-I cells incubated with BMDCs BALB/c alone, or with direct E-ACs, does not induce proliferation, indicating that the only way that OT-I proliferate by Allogeneic DCs (BALB/c) is that they have been loaded with the SIINFEKL/MHC-I peptide from ACs expressing P2X7. All the controls (positive and negative) used are shown in Figure S6. In addition, in most controls, we observe many dead cells, likely because of lack of growth stimuli in these OT-I cultures, where the proliferation observed in some controls is suggested as a background signal.

Figure 4.

P2X7-dependent cross-dressing induces the proliferation of CD8+ OT-1 lymphocytes

In a 1:1 ratio 1 x 105 CT Violet OT-1 lymphocytes were co-cultivated with allogeneic BMDC-BALB/c. The proliferation round of OT-1 lymphocytes was determined by the decrease in CT Violet fluorescence and counting peaks to the left. Representative histograms from 3 to 6 independent experiments.

(A) Proliferation rounds of OT-1 lymphocytes incubated with BMDC-BALB/c previously challenged with E-ACs (blue) and E-ACs-P2X7 (red) both loaded with SIINFEKL.

(B) The percentage of CD8+ OT-1 cells that completed a proliferation cycle (1–6) is shown for each treatment.

(C) The % CD25 + CD8+ OT-1 lymphocytes after stimulation. OT-1 CD8+ lymphocytes were incubated for 24 h with BMDC-BALB/c challenged with E-ACs (blue) and E-ACs-P2X7 (red) both SIINFEKL-loaded. The CD25 + CD8+ OT-1 population of each condition was normalized against untreated OT-1 splenocytes. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Results were analyzed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney test, ∗ p < 0.05

The proliferation of OT-I lymphocytes is directly related to their activation and positive regulation of the CD25 receptor, the high-affinity IL-2 receptor (Ross and Cantrell, 2018). BMDC-BALB/c challenged with E-ACs/SIINFEKL induced modest levels of CD25 expression (7%) (Figure 4C). In contrast, H-2d BMDCs-BALB/c challenged with E-ACs-P2X7/SIINFEKL induced CD25 expression in a higher percentage in OT-I cells (14%). Positive control of stimulation of OT-I by Syngeneic C57BL/6 (B6) BMDC pulsed with the SIINFEKL peptide, up to 40% of OT-I cells expressing CD25 (data not shown). As in the proliferation analyzes, a high cell death was observed in most of the controls because of lack of stimulation of the lymphocytes, like what has been previously reported (Rathmell et al., 2000). Therefore, the measurement of CD25 under these conditions was not performed. Altogether, these results demonstrate for the first time that P2X7 is required for the functional cross-dressing of DCs.

P2X7 supports antigen transfer from apoptotic cells to dendritic cells cytoplasm

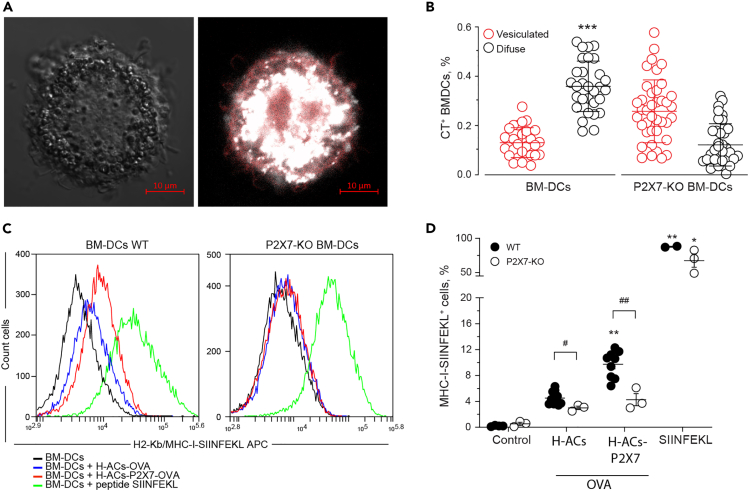

Because cross-dressing requires membrane transfer, and transfer of membrane patches requires a complete or transient fusion of both donor and acceptor membrane, the P2X7R might contribute to this process by accelerating or even allowing membrane fusion (Chiozzi et al., 1997; Lemaire et al., 2006). P2X7R-mediated membrane fusion has been shown to require P2X7R localization at the cell-cell contact sites (Falzoni et al., 2000), in line with the requirement that this receptor must be present on both membranes to achieve ACs-to-DCs membrane transfer. We hypothesized that, if the cross-dressing mechanism involved in membrane transfer requires membrane fusion, we should be able to detect antigen transfer from ACs to the cytoplasm of DCs by fluorescence microscopy. To address this issue, we generated ACs from HEK293 and HEK293-P2X7 by starvation, previously loaded with cytoplasmic probe Cell Tracker (CT). CT-labeled H-ACs were used to challenge MutuDCs and CT transfer was evaluated by fluorescence measurements in a defined ROI. To measure cytoplasmic fluorescence, ROI was defined within the cell body, separated from the initial ACs contact zone. MutuDCs challenged with CT H-ACs-P2X7 and CT H-CAs for 1 h, showed no diffuse increase in cytoplasmic fluorescence (Figures S7A and S7B), suggesting that CT is not being transferred to DC cytoplasm, or if it is, this occurs at undetectable levels. On the contrary, we observed many intracellular CT-loaded small vesicles, suggesting ACs uptake (Figure S7C). This was confirmed by orthogonal reconstruction (Figures S7D and S7F) (Videos S3 and S4). To address if CT transfer to the cytoplasm occurs over longer incubation times, we analyzed MutuDC fluorescence after 18 h incubation with CT H-ACs and H-ACs-P2X7. Under the second condition, we observed a diffuse pattern of CT fluorescence in MutuDCs (Figure 5A), which was confirmed by orthogonal reconstruction (Figure S8). Diffuse cytoplasmic fluorescence was stronger in WT-versus P2X7-KO-BMDCs (Figure S9), consistent with CT leakage from ACs into the cytoplasm of BMDCs (Figure 5B). Thus, these set of experiments confirmed that the P2X7R facilitates antigen transfer from ACs to DCs.

Figure 5.

Membrane transfer from H-ACs to DCs comprises membrane fusion

(A) HEK293 cells were loaded with CellTracker (CT) before generating ACs. MutuDCs were challenged with the CT ACs and the CT transference was evaluated after 18 h. A representative bright-field photograph of cells is shown in the left panel. MutuDCs eEGF (red pseudocolor) merged with Celltracker (white pseudocolor) is shown in the right panel. Scale bar 10 µm.

(B) WT BM-DCs or P2X7-KO BM-DCs were challenged with CT H-ACs-P2X7. CT transference and its cell distribution on WT BM-DCs (black) and P2X7-KO BM-DCs (red) were evaluated 24 h following the challenge. CT distribution showed different cell patterns: cells with perinuclear or vesiculated distribution, and cells with a diffused fluorescence distribution into the cytoplasm. Cells with no incorporation were also observed (not shown). Results for 2–3 independent experiments were quantified and graphed.

(C) Representative histograms show the SIINFEKL/H-2Kb transference from H-ACs expressing cytoplasmic-OVA to BMDCs. The presence of the SIINFEKL/H-2Kb (SIINFEKL/MHC-I) complex was evaluated using a monoclonal antibody (clone eBio25D1.16 APC) in the CD11c+ DC population. WT BM-DCs (left) and P2X7-KO BM-DCs (right) challenged with H-ACs-OVA (blue) or H-ACs-OVA-P2X7 (red). As negative and positive controls were BMDCs not challenged (black) and incubated with SIINFEKL (green), respectively.

(D) Graph of summarized results from peptide/MHC transference experiment. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Results were analyzed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney test, ∗ p < 0.05 and ∗∗ p < 0.01 and ∗∗∗ p < 0.005; compared against vesiculated condition (B) and H-ACs-OVA-P2X7 condition was compared with H-ACs-OVA (D). # p < 0.05 and ## p<0.01; indicate differences between conditions.

CellTracker Green-CMFDA transfer from P2X7 H-ACs to Mutu1940 dendritic cells. Mutu1940 dendritic cells expressing eGFP (red pseudocolor) and H-ACs-P2X7 labeled with CellTracker (CT) Green-CMFDA in their cytoplasm (white pseudocolor). The size scale is displayed at the bottom of the video and the elapsed minutes at the top right. Representative of 5 independent experiments.

CellTracker Green-CMFDA transfer from parental H-ACs to Mutu1940 dendritic cells. Mutu 1940 dendritic cells expressing eGFP (red pseudocolor) and parental H-ACs labeled with CellTracker (CT) Green-CMFDA in their cytoplasm (white pseudocolor). The size scale is displayed at the bottom of the video and the elapsed minutes are displayed at the top right. Representative of 4 independent experiments.

So far, we have determined that the P2X7R promotes transfer of Ag/MHC I complex-containing membrane patches and luminal content from ACs to both DCs plasma membrane zone and DC cytoplasm, and therefore presumably also of soluble Ags. To verify whether P2X7 facilitates the transfer of peptide antigens from ACs to DCs cytoplasm, H-2Kb BMDCs (B6) were challenged with ACs generated from internal OVA-expressing HEK293 (H-ACs-OVA) or P2X7R-transfected, OVA-expressing HEK293 (H-ACs-P2X7-OVA) cells. Twenty-four hours later, we evaluated expression of the SIINFEKL/H-2Kb complex in BMDCs cells by flow cytometry. Incubation in the presence of H-ACs-P2X7-OVA increased SIINFEKL/H-2Kb levels on WT BMDCs (Figure 5C left), in agreement with similar previous reports (Li et al., 2008; Morales et al., 2017), but not in P2X7R- KO BMDCs (Figure 5C right and 5D). Altogether, this data indicates that membrane transfer from ACs to DCs also comprises membrane fusion, verified by transfer of CT and antigens from ACs to DC's cytoplasm. Finding SIINFEKL/H-2Kb in H-2b BMDCs means that DCs were able to obtain and present antigens from H-ACs. This observation suggests that P2X7 can not only support cross-dressing but also cross-presentation. The overall results are summarized in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Proposed mechanism of action. Immature DCs phagocyte normal ACs, overexpressing P2X7

Once incorporated, ACs and DCs membrane fusion is induced (shown in red square), transferring cytoplasmic antigen from ACs to DCs. In addition, membrane transfer induces antigen-loaded MHC transfer, triggering antigen-specific T cell proliferation

Discussion

Here we demonstrated that the P2X7R mediates membrane transfer from ACs to DC as this is associated with transfer of functional peptide/MHC complexes capable of inducing OT-I cell proliferation. Although the detailed mechanism remains to be elucidated, we showed that transfer depends on the expression of the P2X7R in both ACs and DCs, consistent with the hypothesis proposed by Falzoni et al. (2000) that in the cell fusion process, the P2X7R must be expressed at the sites of cell-cell contact on both the interacting cells (Falzoni et al., 2000). Our results support the view that CA-to-DC membrane transfer requires membrane fusion, as P2X7R expression also facilitates the transfer of soluble antigens from ACs to DC cytoplasm, thus allowing cross-presentation.

The general mechanism for the fusion of lipid bilayers involves phospholipid-dependent induction of membrane curvature at the site of fusion (Martens and McMahon, 2008). The importance of the lipid composition of the membrane and activity of phospholipases, such as sphingomyelinase, phospholipase C, and phospholipase D, for the membrane fusion, has been extensively studied (Goñi, 2000, 2014; Jouhet, 2013). P2X7R-mediated cell-to-cell fusion in vitro has been described widely in P2X7R-transfected HEK293 cells, macrophages (Chiozzi et al., 1997), and osteoclasts (Pellegatti et al., 2011). Relevant to membrane fusion, the P2X7R activates several signaling pathways possibly involved, including phospholipases A2, D, and C, neutral sphingomyelinase (Alzola et al., 1998; Kopp et al., 2019; Pellegatti et al., 2011), and also triggers ROCK and p38-dependent actin reorganization (Whitfield et al., 2002). Several additional P2X7R-associated responses might also promote or facilitate membrane fusion. For example, the well-known P2X7R-associated “macropore” might participate in the formation of the “fusion pore” needed to initiate membrane fusion (Di Virgilio, 1995). Alternatively, the scavenger activity of the P2X7R may be required to recognize and process “eat-me” signals exposed on the surface of ACs and allow resealing of juxtaposed membranes (Gu et al., 2011). In this line, other receptors such as the C-type lectin receptor CLEC9A involved in sensing necrotic cells have been associated with membrane fusion during antigen cross-presentation (Schreibelt et al., 2012).

Indirect evidence supports a role of the P2X7R in in vivo antigen presentation and T lymphocyte priming by DC. For instance, in cancer, the P2X7R is essential for antitumor immune response (Ghiringhelli et al., 2009) and the absence of the P2X7R in mice is associated with accelerated tumor progression (Adinolfi et al., 2015). Our research makes sense and is correlated with recent research, which reports that, during an infection or pathology, the levels of P2X7R in blood plasma are increased compared to healthy patients. These P2X7 receptors are associated with microvesicles or microparticles from infectious or cancerous tissue (Giuliani et al., 2019). This suggests that in certain conditions, cross-dressing could be favored to conduct an immune response mediated by this receptor. In the immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), in vivo activation of CD8+ T cell-specific response requires apoptotic cells (ACs) released from mycobacteria-infected macrophages (Boom, 2007; Mohagheghpour et al., 1998; Schaible et al., 2003), which facility the antigen cross-priming (Ramachandra et al., 2010) through either a conventional mechanism of DC cross-presentation (Hartman and Kornfeld, 2011) or a CD8+gamma delta-mediated mechanism of non-conventional cross-presentation (Brandes et al., 2009). Interestingly, the 1513A > C (Glu 496 Ala) loss-of-function SNP which generates a defective P2X7R (Bu et al., 2021), impairs the response against MTB and allows the survival of mycobacteria within the mice host cells (Saunders et al., 2003). In addition, the same SNP has been reported to be a risk factor for pulmonary tuberculosis in subjects of Asian, but not African or Latin-American, ethnicity (Custodio et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2014).

Besides the E496A, several other loss- (e.g., R276H, R307Q, and I568N) or gain-of-function (e.g., H155Y, H270R) SNPs have been identified in the P2X7R, which by impairing macropore formation might also affect membrane fusion (Lara et al., 2020). Several P2X7 splice variants have been identified, among which P2X7B is most closely characterized. This variant encodes a truncated P2X7 subunit lacking 249 C-terminal aa residues and incorporating 18 extra aa after residue 346 (Sun et al., 2010). The P2X7B receptor maintains the channel function but is unable to generate the macropore, thus in principle it should not promote membrane fusion or Ag presentation or cross-dressing. Overall, the role of the P2X7R in Ag presentation is still largely unexplored. Ever since the first observations by Mutini et al. PMID: 10438932, few studies investigated the role of this receptor in the stimulation of T lymphocytes by antigen-presenting cells. Early studies showed that stimulation by extracellular ATP of the P2X7R of MTB-infected macrophages triggered release of MHCII-bearing exosomes capable of presenting MTB Ags (Qu et al., 2009; Ramachandra et al., 2010), but whether the P2X7R was expressed on the exosomes, and whether there was a requirement for P2X7R expression on the responding T cells was not investigated.

In the light of accumulating evidence supporting the participation of the P2X7R in the activation of the immune response, we are confident that an in-depth investigation of the participation of this receptor to Ag processing and investigation will provide new insights in the pathogenesis of immune-mediated diseases and novel therapeutics (Cao et al., 2019; Linden et al., 2019).

Limitations of the study

Although we observed transfer of the CellMask membrane dye between the ACs and the surface of the DCs, we suggest that this occurs in an area mainly composed of plasma membrane; however, a characterization by electron microscopy is needed to verify this structure. Furthermore, we agree that the use of the EG7 cell model with EL4-SIINFEKL would rule out a possible nonspecific binding of traces of the SIINFEKL peptide present in the cell medium during the E-ACs SIINFEKL load, despite this is highly unlikely considering the protocol used in this study. Finally, to evaluate the final process of cross-presentation of the OVA antigen, it is required to evaluate the use of a lymphocyte proliferation, although this was not the main objective of the study, it will give cues of the possible mechanism of membrane fusion between ACs and DCs. Despite these limitations, the findings and conclusions of the study are supported by our results.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| P2X7 Polyclonal Antibody | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT#PA5-28020; RRID: AB_2545496 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, HRP | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT#A16110; RRID: AB_2534782 |

| CD11c Monoclonal Antibody (N418), PE | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT#12-0114-82; RRID: AB_465552 |

| MHC Class II (I-A/I-E) Monoclonal Antibody (M5/114.15.2), FITC | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT#11-5321-82; RRID: AB_465232 |

| CD16/CD32 Monoclonal Antibody (93) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT#14-0161-82; RRID: AB_467133 |

| FITC anti-mouse CD11c Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#117306; RRID: AB_313775 |

| OVA257-264 (SIINFEKL) peptide bound to H-2Kb Monoclonal Antibody (25-D1.16), APC | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT# 17-5743-82; RRID: AB_1311286 |

| PE Rat Anti-Mouse CD25 | BD Bioscience | CAT# 561065; RRID: AB_395101 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| pcDNA3-OVA plasmid | Diebold SS et al., 2001 | RRID: Addgene_64599 |

| P2X7-pIRES2/eGFP plasmid | Genscript Biotech | N/A |

| P2X7-pcDNA3.1 Hygro(+) plasmid | Genscript Biotech | N/A |

| Biological samples | ||

| Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) from BALB/CJ, C57BL/6 and P2X7KO mice | Eduardo Morales Santos Facility of Universidad de Santiago de Chile | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Recombinant Mouse GM-CSF | Biolegend | CAT# 576304; Accession # NM_009969 |

| Mouse IL-4 Recombinant Protein | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT#RMIL4I; GenBank Accession # P07750 |

| Lipofectamine™ 2000 Transfection Reagent | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT# 11668019 |

| Selection antibiotic G418 | Merck | CAT#345810; CAS 108321-42-2 |

| Hygromycin B (50 mg/ml) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT# 10687010 |

| CellTracker™ Red CMTPX Dye | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT# C34552 |

| CellTracker™ Orange CMRA Dye | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT# C34551 |

| CellMask™ Deep Red Plasma membrane Stain | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT# C10046 |

| Ovalbumin (257-264) chicken ≥97% | Sigma-Aldrich | N/A |

| 7-AAD Viability Staining Solution | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT#00-6993-50 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Dead Cell Apoptosis Kit with Annexin V Alexa Fluor™ 488 and Propidium Iodide (PI) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT# V13241 |

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| Mutu1940 | Faculty of Chemical Sciences, National University of Córdoba, Argentina. Dr. Gabriel Morón | N/A |

| EL-4 | ATCC | CAT#TIB-39 |

| HEK293 | ATCC | CAT#CRL-1573 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: BALB/cJ | The Jackson Laboratory | CAT# 000651 |

| Mouse: C57BL/6J | The Jackson Laboratory | CAT# 000664 |

| Mouse: B6.129P2-P2RX7tm1Gab (P2X7 KO) | The Jackson Laboratory | CAT# 005576 |

| Mouse: C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J (OT-1) | The Jackson Laboratory | CAT#003831 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism version 8.01 | GraphPad Software, Inc. | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| FlowJo 10.4 | Becton Dickinson | https://www.flowjo.com/solutions/flowjo/downloads/previous-versions |

| BD Accuri™ C6 plus | Becton Dickinson | https://www.bdbiosciences.com/en-us/products/instruments/flow-cytometers/research-cell-analyzers/bd-accuri-c6-plus |

| ZEN 2.6 blue edition | Carl Zeiss | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/int/products/microscope-software/zen-lite.html |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Claudio Acuña-Castillo (claudio.acuna@usach.cl)

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique materials.

Experimental model and subject details

Animals

Healthy Male or Female BALB/c, C57BL/6, or B6.129P2-P2RX7tm1Gab (P2X7KO) 6–12 weeks old mice were obtained from the “Eduardo Morales Santos Facility” of Universidad de Santiago de Chile. OT-I mice (Jackson laboratory, stock Nº003831) were obtained from the Science Facility of the University of Chile. The animals were housed and fed ad libitum with 12/12 h light/dark cycles. The ethics and animal handling protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the University of Santiago de Chile, with approval number No. 600. All procedures were conducted following the guidelines on the recognition of animal pain, distress, and discomfort.

Cell lines

HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). EL-4 and Mutu1640 dendritic cells (DCs) were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). MutuDCs (Steiner et al., 2008) kindly provided by Dr. Moron, stably expresses green fluorescent protein (eGFP) gene under the control of CD11c promoter. The culture medium for HEK293 and EL-4 cell lines was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, while the medium for Mutu1940 culture was supplemented with 15% of FBS. The culture medium was supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2.5 μg/mL amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Cell lines were kept at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere under 5% CO2.

Primary cultures

Primary cultures of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were generated from bone marrow precursors of male and female wild-type C57BL/6 (WT), deficient for P2X7 receptor (P2X7KO) and BALB/c mice. The animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and the femur and tibia were removed under sterile conditions. The ends were removed and perfused with RPMI-1640 medium. The cells obtained were centrifuged at 300 g for 10 minutes. The pellet was resuspended in ACK erythrocyte lysis solution (0.15 M NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO, 0.1 mM EDTA) for 5 minutes with gentle shaking at room temperature, followed by centrifugation at 300 g for 7 minutes. The cell pellet was resuspended and seeded in a 24-well plate (1.0 x 106 cells per well) with RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (100U/mL)/streptomycin (100μg/mL), 1mM pyruvate, 1mM L-glutamine, 1% non-essential amino acids, 10 ng/mL of GM-CSF (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA) and 5 ng/mL of IL-4 (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). After two days, 75% of the culture medium was renewed. On the fourth and sixth day, supplemented RPMI medium without cytokines was used to replace the old medium. Cells were used on the seventh day for each experimental assay.

Method details

Cell transfection

P2X7 rat gene into pCI-neo and pcDNA3.1Hygro (+) vectors were synthesized by Genscript (NJ, USA). pcDNA3-OVA plasmid was purchase from Addgene (plasmid #64599). This plasmid is a truncated OVA version at the N-terminus (amino acids 49–386) that lacks the secretion signal sequence. HEK293 cell line was transfected with rat P2X7-pIRES2/eGFP, P2X7-pcDNA3.1 Hygro(+) or pcDNA3-OVA (P2X7 HEK293 cell line) using lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following manufacturer's instructions. Stables clones were isolated and expanded using 500 μg/mL of the selection antibiotic G418 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) or 200μg/mL Hygromycin B (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), according to the vector. EL4 cells were transfected with 50μg of pCi-neo-P2X7 plasmid (P2X7 EL-4 cell line), 120 Volts, 960 μF and ∞Ω in a BioRad Gene Pulser (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and 200 μg/ml of G418 antibiotic was used to generate a stable selection.

Apoptosis Cells (ACs) generation

To obtain total Apoptosis Cells (ACs) from parental EL4, HEK293, P2X7 EL4, P2X7 HEK293 cell lines were subjected to starvation, as previously described by our group (Morales et al., 2017). Briefly, adherent cells were seeded and cultured up to 70% confluence or 1x106 cells in 35mm2 plates. Then cells were washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and cultured in nutrient-deprived PBS, containing 2.5 μg/mL fungizone and 10 μg/mL Gentamicin (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for one week at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere under 5% CO2. On day seven, all cells are detached, and the PBS containing total ACs was collected and centrifuged at 400g, washed twice, and used immediately. For the E-ACs characterization, EL4 cells were previously labeled with CellTracker™ red (CMTPX, Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and ACs were generated as indicated previously. E-ACs-apoptosis analysis was analyzed using the Dead Cell Apoptosis Kit with Annexin V Alexa Fluor™ 488 and Propidium Iodide (PI) (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to evaluate cell viability/apoptosis, following the manufacturers. Samples were observed by confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 800 confocal microscope, Carl Zeiss, Inc) and analyzed using Zeiss LSM 2,5 Blue software.

Western blot and ethidium bromide uptake

The expression of P2X7 receptor in live EL4 cells, E-ACs, EL4 P2X7, and E-ACs-P2X7, was confirmed and detected with a Western Blot (WB) using the polyclonal antibody-P2X7 (Clone: PA528020) and secondary anti-rabbit IgG HRP-Linked (Clone: A16110), both from (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Briefly, 2 x 105 live cells and ACs were lysed in 4X loading buffer heated to 70°C with β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The lysed samples were transferred to a 1.5mL Eppendorf tube and heated at 95°C for 5 minutes using a thermo-block (AccuBlock Digital Dry Bath-Labnet). The samples were stored at −80°C until the WB was performed using the Tetra-cell Bio Rad mini-protean equipment (BioRad, Hercules, CA). P2X7 receptor was evaluated, by ethidium bromide (BrET) uptake (Leiva-Salcedo et al., 2011). Briefly, Mutu1940, HEK293, P2X7 HEK293 cells, and BMDCs BALB/c were incubated up to 70% confluence under culture conditions, in 35mm2 plates in DMEM medium supplemented 10% without phenol red. Subsequently, the plates were mounted on a stage thermoregulated at 37°C of the LSM 800 microscope with an atmosphere of 5% CO2. After 5 minutes, BrEt (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to a final concentration of 20 μg/mL. The cells were challenged with 1mM ATP (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). On some occasions, the P2X7 inhibitor, A740003, was used at 100μM for 30 minutes, before the addition of ATP. BrEt uptake was determined by 30 minutes, and TritonX-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as a positive permeabilization control. The analysis was performed with the ZEN 2.6 blue edition software of the LSM 800 confocal microscope, using a 40x NA long-pass objective (Carl Zeiss, Inc).

Phagocytosis and BMDCs maturation

For the phagocytosis assay, previously generated BM-DCs from (Wild type) WT and P2X7KO mice were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere under 5% CO2 with 2x105 H-ACs (from HEK293 cell line) and H-ACs-P2X7 (from P2X7 overexpressing HEK293 cell line) previously labeled with CellTracker™ Orange (CMRA), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. For negative control, BM-DCs were incubated with unlabeled ACs, while yellow-green latex beads (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were used as a positive control. After incubation, BMDCs were collected and the CMRA fluorescence was detected in the total CD11c+ positive population by flow cytometry using anti-mouse CD11c FITC (Clone: N418). ACs and dead BMDCs were excluded by 7-AAD (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) staining to minimize non-specific ACs binding to BM-DCs.

OVA cross-presentation assay

For the evaluation of antigen cross-presentation, WT and P2X7KO BM-DCs were stimulated for 24 h with H-AC-OVA and H-ACs-OVA-P2X7, in a 2:1 ratio of ACs/BM-DCs. As a positive control, BM-DCs were incubated with 5 μM of OVA257-264 peptide (SIINFEKL, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 180 min at 37° C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After the pulse period, BMDCs labeling was performed with the anti-mouse- CD11c FITC and anti-mouse OVA antibodies (SIINFEKL/H-2Kb, clone eBio25D1.16 APC) from, both from eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA. Total viable cells were evaluated by PI + exclusion. SIINFEKL/MHC-I complex was analyzed in the BM-DCs surface using the Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer and the information was processed using CFlow Plus software (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA)

Antigen cross-dressing ex vivo

Mutu1940 (MutuDCs) cells, BMDCs and P2X7KO BMDCs were used as cell acceptors. The DCs were seeded and maintained on 24 mm coverslips under culture conditions. At the time of each experiment, the coverslip was removed and mounted in a tubular cell chamber with phenol red-free culture medium and placed on a thermoregulated stage at 37°C in an environment with 5% CO2 in Carl Zeiss confocal microscope LSM 800. Subsequently, 1 x 105 ACs previously labeled with CM were added directly to the tubular cell chamber containing the DCs (MutuDCs, BM-DCs or P2X7KO BM-DCs), and the images were acquired every 5 seconds for 30 min using a 63x objective; 1.46 NA (Carl Zeiss, Inc). For the analysis of membrane transfer from ACs to the surface of the DCs, a region of the DCs plasma membrane was selected, to measure the increase in fluorescence intensity of the CellMask ™ probe from ACs using ZEN 2.6 blue edition software. At the end of the experiment, Z-Stak (cross-sectional cell imaging planes) and FRAP (Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching) using the voltage in 50% of 640 nm laser were made. On occasions, DCs were pre-incubated with 200 μM of oATP (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 2 hours to test the effect of inhibition of this receptor. For SIINFEKL/H2Kb complex transfer from ACs to DCs, ACs were generated from EL4 and EL4 P2X7 live cells and incubated with 5 μM of the SIINFEKL peptide (OVA257-264) for 3 hours at 37°C in an atmosphere humidified with 5% CO2. After incubation, the ACs were washed three times with PBS and used immediately for each experiment. The E-ACs and E-ACs-P2X7 (Haplotype H-2Kb) loaded with the peptide SIINFEKL were incubated with BMDCs from the mouse strain BALB/c (Haplotype H-2Kd) in a ratio of 2: 1 (ACs: BM -DCs BALB/c) for 18 hours under cell culture conditions in 24 wells plates. After incubation, the BALB/c BMDCs were washed twice with PBS and released with CellScraper. Buffer IF (PBS + 10% SFB) was used and the Fc receptors were blocked using an anti-mouse CD16/32 antibody (Fc Block, Clone: 93, eBioscience, San Diego, California, USA) for 30 min at 4°C. Then the BMDCs BALB/c were labeled with anti-CD11c FITC (Clone: N418) and anti-mouse SIINFEKL/H-2Kb APC (Clone: 25-D1.16, eBioscience, San Diego, California, USA). In the population of total viable cells (negative propidium iodide) and CD11c positive, the fluorescence intensity of the SIINFEKL/H2Kb complex from the ACs was measured, using the Accuri C6 Flow (BD Bioscience) flow cytometer and the data were processed with the CFlow Plus software. On occasions, DCs were pre-incubated with 200 μM of oATP for 2 hours to evaluate the effect of inhibition of this receptor. Similar experiments were done using ACs labeled with CellTracker™ CMPTX (CT, pseudocolor white) generated from HEK293 or HEK293 P2X7, following the manufacturer's instructions. MutuDCs, BMDCs WT, and P2X7 KO were challenged with 1 x 105 H-ACs or H-ACs-P2X7, and the CT transfer from ACs to DCs cytoplasm was analyzed using a 63x objective; 1.46 NA of LSM 800 Carl Zeiss confocal (Carl Zeiss, Inc). Z-stack and FRAP tests were performed as indicated.

OT-I cells activation and proliferation

Naive CD8+ T cells were purified from the spleen and peripheral lymph nodes of OT-I mice. Briefly, the spleen was perfused with RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, red blood cells were lysed and then enriched by negative selection of naive CD8+ T cells using a commercial kit (Naive CD8+ T cell isolation kit- Miltenyi Biotec) following the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, naive CD8+ T cells (CD8+/CD44lo/ CD62Lhi/CD25−) were enriched (up to 99% purity) by cell-sorting isolation using Aria III FACS, BD Biosciences. The cells were then labeled with 5 μM of CellTrace Violet fluorescent probe (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Once labeled with the probe, 1 x 105 naive CD8 + OT-I T cells were incubated with 1 x 105 BALB/c BMDCs previously incubated for 72 h with E-ACs or P2X7 E-ACs loaded or not with SIINFEKL (OVA257-264). As controls, 1 x 105 T CD8 OT-I were incubated with 1 x 105 DCs C57BL/6 loaded with SIINFEKL peptide, or naive CD8+OT-I T lymphocytes were incubated with 2 nM of SIINFEKL peptide. The antigen-specific T cell response was measured by detection of CD25 in lymphocytes with the anti-mouse antibody CD25-PE (BD Biosciences, Clone: PC61.5) and by analysis of proliferation rounds as Cell Trace violet dilution using a cell sorter FACS Aria III and the software FlowJo 10.4.

Quantification and statistical analysis

The transfer of the membrane and the SIINFEKL/H2Kb complex from the ACs to BMDCs, MutuDCs, and activation of T lymphocytes, were analyzed using the non-parametric test of Mann Whitney. For the analysis of slopes in the incorporation of CM fluorescence in the plasma membranes of DC, BrEt uptake, slope analysis for nonlinear regression was used. For all experiments, statistical analyzes were performed with GraphPad Prism version 8.01 (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA). The results are presented as means ± SEM, and statistical differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following funding sources: FONDECYT 1161015 (M.I.), 11140731 (E.L-S.), and 1180666 (A.E.); FONDEQUIP EQM150069 and EQM190024; DICYT 021943AC (C.A-C.) and 021801MB (L.A.M.); and ANID fellowship (C.R-P., C.B-A.). Acknowledgment to Dirección de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica USACH (DICYT).

Author contributions

Conceptualization. C.B-A., C. A-C. Methodology C.B-A., L.A.M., M.I., J.P.H-T., D.S., E. L-S., C. R-P., and A. E. Investigation C.B-A., P.B., O.T., D.V., D.S., E. L-S., and C. R-P. Formal Analysis C.B-A., L.E.R., C. R-P. Writing – Original Draft, C.B-A., C. A-C., C. R-P. Writing – Review & Editing L.A.M. F.d.V., D.S., L.E.R., G.M., A. E. Funding Acquisition C. A-C., E.L-S., and A.E.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: December 17, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.103520.

Contributor Information

Daniela Sauma, Email: dsauma@uchile.cl.

Claudio Acuña-Castillo, Email: claudio.acuna@usach.cl.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

This paper does not report original code.

References

- Adinolfi E., Capece M., Franceschini A., Falzoni S., Giuliani A.L., Rotondo A., Sarti A.C., Bonora M., Syberg S., Corigliano D., et al. Accelerated tumor progression in mice lacking the ATP receptor P2X7. Cancer Res. 2015;75:635–644. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzola E., Pérez-Etxebarria A., Kabré E., Fogarty D.J., Métioui M., Chaïb N., Macarulla J.M., Matute C., Dehaye J.P., Marino A. Activation by P2X7 agonists of two phospholipases A2 (PLA2) in ductal cells of rat submandibular gland: coupling of the calcium-independent PLA2 with kallikrein secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:30208–30217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroni M., Pizzirani C., Pinotti M., Ferrari D., Adinolfi E., Calzavarini S., Caruso P., Bernardi F., Di Virgilio F. Stimulation of P2 (P2X7) receptors in human dendritic cells induces the release of tissue factor-bearing microparticles. FASEB J. 2007;21:1926–1933. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7238com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera-Avalos C., Mena J., López X., Cappelli C., Neira T., Imarai M., Fernández R., Robles-Planells C., Rojo L.E., Milla L.A., et al. Adenosine triphosphate, polymyxin B and B16 cell-derived immunization induce anticancer response. Immunotherapy. 2021;13:309–326. doi: 10.2217/imt-2020-0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boom W.H. New TB vaccines: is there a requirement for CD8 T cells? J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:2092–2094. doi: 10.1172/JCI32933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges Da Silva H., Beura L.K., Wang H., Hanse E.A., Gore R., Scott M.C., Walsh D.A., Block K.E., Fonseca R., Yan Y., et al. The purinergic receptor P2RX7 directs metabolic fitness of long-lived memory CD8+ T cells. Nature. 2018;559:264–268. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes M., Willimann K., Bioley G., Lévy N., Eberl M., Luo M., Tampé R., Lévy F., Romero P., Moser B. Cross-presenting human γδ T cells induce robust CD8+ αβ T cell responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:2307–2312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810059106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu C., Sadtler S., Boldt W., Klapperstu M., Klapperstu M., Bu C., Sadtler S. Glu 496 Ala polymorphism of human P2X 7 receptor does not affect its electrophysiological phenotype. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2021;284:749–756. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00042.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao F., Hu L.Q., Yao S.R., Hu Y., Wang D.G., Fan Y.G., Pan G.X., Tao S.S., Zhang Q., Pan H.F., Wu G.C. P2X7 receptor: a potential therapeutic target for autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 2019;18:767–777. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2019.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiozzi P., Sanz J.M., Ferrari D., Falzoni S., Aleotti A., Buell G.N., Collo G., Virgilio F.D. Spontaneous cell fusion in macrophage cultures expressing high levels of the P2Z/P2X 7 receptor. J. Cell Biol. 1997;138:697–706. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custodio H., Masnita-Iusan C., Wludyka P., Rathore M.H. Change in rotavirus epidemiology in northeast Florida after the introduction of rotavirus vaccine. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2010;29:766–767. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181dbf256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan B.P., Gibbs K.D., Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Dendritic cells cross-dressed with peptide MHC class I complexes prime CD8 + T cells. J. Immunol. 2006;177:6018–6024. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falzoni S., Chiozzi P., Ferrari D., Buell G., Di Virgilio F. P2x7 receptor and polykarion formation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:3169–3176. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.9.3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiringhelli F., Apetoh L., Tesniere A., Aymeric L., Ma Y., Ortiz C., Vermaelen K., Panaretakis T., Mignot G., Ullrich E., et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in dendritic cells induces IL-1Β-dependent adaptive immunity against tumors. Nat. Med. 2009;15:1170–1178. doi: 10.1038/nm.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani A.L., Berchan M., Sanz J.M., Passaro A., Pizzicotti S., Vultaggio-poma V., Sarti A.C. The P2X7 receptor is shed into circulation : correlation with C-Reactive protein levels. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goñi A.A. Membrane fusion induced by phospholipase C and sphingomyelinases. Biosci. Rep. 2000;20:443–463. doi: 10.1023/a:1010450702670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goñi F.M. The basic structure and dynamics of cell membranes: an update of the Singer-Nicolson model. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr. 2014;1838:1467–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu B.J., Saunders B.M., Petrou S., Wiley J.S. P2X7 is a scavenger receptor for apoptotic cells in the absence of its ligand, extracellular ATP. J. Immunol. 2011;187:2365–2375. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman M.L., Kornfeld H. Interactions between naïve and infected macrophages reduce Mycobacterium tuberculosis viability. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouhet J. Importance of the hexagonal lipid phase in biological membrane organization. Front. Plant Sci. 2013;4:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp R., Krautloher A., Ramírez-Fernández A., Nicke A. P2X7 interactions and signaling – making head or tail of it. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019;12:1–25. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara R., Adinolfi E., Harwood C.A., Philpott M., Barden J.A., Di Virgilio F., McNulty S. P2X7 in cancer: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutics. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecciso M., Ocadlikova D., Sangaletti S., Trabanelli S., De Marchi E., Orioli E., Pegoraro A., Portararo P., Jandus C., Bontadini A., et al. ATP release from chemotherapy-treated dying leukemia cells Elicits an immune suppressive effect by increasing regulatory T cells and Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Front. Immunol. 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiva-Salcedo E., Coddou C., Rodríguez F.E., Penna A., Lopez X., Neira T., Fernández R., Imarai M., Rios M., Escobar J., et al. Lipopolysaccharide inhibits the channel activity of the P2X7 receptor. Mediators Inflamm. 2011;2011:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2011/152625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire I., Falzoni S., Leduc N., Zhang B., Pellegatti P., Adinolfi E., Chiozzi P., Di Virgilio F. Involvement of the purinergic P2X 7 receptor in the formation of multinucleated giant cells. J. Immunol. 2006;177:7257–7265. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Wang L.-X., Yang G., Fang H., Urba W.J., Hu H.-M. Efficient cross-presentation depends on autophagy in tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2008;16:6889–6895. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden J., Koch-Nolte F., Dahl G. Purine release, metabolism, and signaling in the inflammatory response. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2019;26:325–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-051116-052406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens S., McMahon H.T. Mechanisms of membrane fusion: disparate players and common principles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:543–556. doi: 10.1038/nrm2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohagheghpour N., Gammon D., Kawamura L.M., van Vollenhoven A., Benike C.J., Engleman E.G. CTL response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis: identification of an immunogenic epitope in the 19-kDa lipoprotein. J. Immunol. 1998;161:2400–2406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra A.D., Tirrell I., Benechet A.P., Pattnayak S., Khanna K.M., Srivastava P.K. Cross-dressing of CD8aþ dendritic cells with antigens from live mouse tumor cells is a major mechanism of cross-priming. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020;8:1287–1299. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-20-0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales J., Barrera-Avalos C., Castro C., Castillo S., Barrientos C., Robles-Planells C., López X., Torres E., Montoya M., Cortez-San Martín M., et al. Dead tumor cells expressing infectious salmon anemia virus fusogenic protein favor antigen cross-priming in Vitro. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:1170. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgia M., Hanau S., Pizzo P., Rippa M., Di Virgilio F. Oxidized ATP. An irreversible inhibitor of the macrophage purinergic P(2Z) receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:8199–8203. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9258(18)53082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutini C., Falzoni S., Ferrari D., Chiozzi P., Morelli A., Baricordi O.R., Collo G., Ricciardi-Castagnoli P., Di Virgilio F. Mouse dendritic cells express the P2X7 purinergic receptor: characterization and possible participation in antigen presentation. J. Immunol. 1999;163:1958–1965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama M. Antigen presentation by MHC-dressed cells. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegatti P., Falzoni S., Donvito G., Lemaire I., Di Virgilio F. P2X7 receptor drives osteoclast fusion by increasing the extracellular adenosine concentration. FASEB J. 2011;25:1264–1274. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-169854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y., Ramachandra L., Mohr S., Franchi L., Clifford V., Nunez G., Dubyak G.R. P2X7 receptor-stimulated secretion of MHC-II-containing exosomes requires the ASC/NLRP3 inflammasome but is independent of caspase-1. J. Immunol. 2009;182:5052–5062. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandra L., Qu Y., Wang Y., Lewis C.J., Cobb B.A., Takatsu K., Boom W.H., Dubyak G.R., Harding C.V. Mycobacterium tuberculosis synergizes with ATP to induce release of microvesicles and exosomes containing major histocompatibility complex class II molecules capable of antigen presentation. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:5116–5125. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01089-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathmell J.C., Heiden M.G.V., Harris M.H., Frauwirth K.A., Thompson C.B. In the absence of extrinsic signals, nutrient utilization by lymphocytes is insufficient to maintain either cell size or viability. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:683–692. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Yáñez E., Barrera-Avalos C., Parra-Tello B., Briceño P., Rosemblatt M.V., Saavedra-Almarza J., Rosemblatt M., Acuña-Castillo C., Bono M.R., Sauma D. P2x7 receptor at the crossroads of t cell fate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:1–22. doi: 10.3390/ijms21144937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S.H., Cantrell D.A. Signaling and function of interleukin-2 in T lymphocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2018;36:411–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sáez P.J., Vargas P., Shoji K.F., Harcha P.A., Sáez J.C. ATP promotes the fast migration of dendritic cells through the activity of pannexin 1 channels and P2X 7 receptors. Sci. Signal. 2017;10:1–12. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aah7107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders B.M., Fernando S.L., Sluyter R., Britton W.J., Wiley J.S. A loss-of-function polymorphism in the human P2X 7 receptor Abolishes ATP-mediated killing of mycobacteria. J. Immunol. 2003;171:5442–5446. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savio L.E.B., Mello P.de A., da Silva C.G., Coutinho-Silva R. The P2X7 receptor in inflammatory diseases: Angel or demon? Front. Pharmacol. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaible U.E., Winau F., Sieling P.A., Fischer K., Collins H.L., Hagens K., Modlin R.L., Brinkmann V., Kaufmann S.H.E. Apoptosis facilitates antigen presentation to T lymphocytes through MHC-I and CD1 in tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 2003;9:1039–1046. doi: 10.1038/nm906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibelt G., Klinkenberg L.J.J., Cruz L.J., Tacken P.J., Tel J., Kreutz M., Adema G.J., Brown G.D., Figdor C.G., De Vries I.J.M. The C-type lectin receptor CLEC9A mediates antigen uptake and (cross-)presentation by human blood BDCA3+ myeloid dendritic cells. Blood. 2012;119:2284–2292. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-373944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner Q.G., Otten L.A., Hicks M.J., Kaya G., Grosjean F., Saeuberli E., Lavanchy C., Beermann F., McClain K.L., Acha-Orbea H. In vivo transformation of mouse conventional CD8α+ dendritic cells leads to progressive multisystem histiocytosis. Blood. 2008;111:2073–2082. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-097576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Chu J., Singh S., Salter R.D. Identification and characterization of a novel variant of the human P2X7 receptor resulting in gain of function. Purinergic Signal. 2010;6:31–45. doi: 10.1007/s11302-009-9168-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Virgilio F. The P2Z purinoceptor: an intriguing role in immunity, inflammation and cell death. Immunol. Today. 1995;16:524–528. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80045-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Virgilio F., Dal Ben D., Sarti A.C., Giuliani A.L., Falzoni S. The P2X7 receptor in infection and inflammation. Immunity. 2017;47:15–31. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakim L.M., Bevan M.J. Cross-dressed dendritic cells drive memory CD8+ T-cell activation after viral infection. Nature. 2011;471:629–632. doi: 10.1038/nature09863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield M.L., Sherlock G., Saldanha A.J., Murray J.I., Ball C.A., Alexander K.E., Matese J.C., Perou C.M., Hurt M.M., Brown P.O., et al. Human cell cycle and their expression in tumors. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:1977–2000. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Zhao M., Gu X., Yao Y., Hongbing Liu Y.S. The effect of P2X7 receptor 1513 polymorphism on susceptibility to tuberculosis: a meta-analysis. Infect Genet. Evol. 2014;24:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng F., Morelli A.E. Extracellular vesicle-mediated MHC cross-dressing in immune homeostasis, transplantation, infectious diseases, and cancer. Semin. Immunopathol. 2018;40:477–490. doi: 10.1007/s00281-018-0679-8. Extracellular. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Membrane transfer from P2X7 H-ACs to Mutu1940 dendritic cells. Mutu1940 dendritic cells expressing eGFP (red pseudocolor) and H-ACs-P2X7 labeled on their membrane with the lipophilic marker CellMask (CM) DeepRed (green pseudocolor). The size scale is displayed at the bottom of the video and the elapsed minutes are displayed at the top right. Representative of 3 independent experiments.

Membrane transfer from parental H-ACs to Mutu dendritic cells. MutuDCs expressing eGFP (red pseudocolor) and H-ACs-P2X7 labeled the CellMask (CM) DeepRed membrane marker (green pseudocolor). The size scale is displayed at the bottom of the video and the elapsed minutes are displayed at the top right. Representative of 4 independent experiments.

CellTracker Green-CMFDA transfer from P2X7 H-ACs to Mutu1940 dendritic cells. Mutu1940 dendritic cells expressing eGFP (red pseudocolor) and H-ACs-P2X7 labeled with CellTracker (CT) Green-CMFDA in their cytoplasm (white pseudocolor). The size scale is displayed at the bottom of the video and the elapsed minutes at the top right. Representative of 5 independent experiments.

CellTracker Green-CMFDA transfer from parental H-ACs to Mutu1940 dendritic cells. Mutu 1940 dendritic cells expressing eGFP (red pseudocolor) and parental H-ACs labeled with CellTracker (CT) Green-CMFDA in their cytoplasm (white pseudocolor). The size scale is displayed at the bottom of the video and the elapsed minutes are displayed at the top right. Representative of 4 independent experiments.

Data Availability Statement

This paper does not report original code.