Abstract

Purpose

The National Colorectal Cancer Cohort (NCRCC) study aims to specifically assess risk factors and biomarkers related to endpoints across the colorectal cancer continuum from the aetiology through survivorship.

Participants

The NCRCC study includes the Colorectal Cancer Screening Cohort (CRCSC), which recruited individuals who were at high risk of CRC between 2016 and 2020 and Colorectal Cancer Patients Cohort (CRCPC), which recruited newly diagnosed patients with CRC between 2015 and 2020. Data collection was based on questionnaires and abstraction from electronic medical record. Items included demographic and lifestyle factors, clinical information, survivorship endpoints and other information. Multiple biospecimens including blood, tissue and urine samples were collected. Participants in CRCSC were followed by a combination of periodic survey every 5 years and annual linkage with regional or national cancer and death registries for at least 10 years. In CRCPC, follow-up was conducted with both active and passive approaches at 6, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48 and 60 months after surgery.

Findings to date

A total of 19 377 participants and 15 551 patients with CRC were recruited in CRCSC and in CRCPC, respectively. In CRCSC, 48.0% were men, and the average age of participants at enrolment was 58.7±8.3 years. In CRCPC, 61.4% were men, and the average age was 60.3±12.3 years with 18.9% of participants under 50 years of age.

Future plans

Longitudinal data and biospecimens will continue to be collected. Based on the cohorts, several studies to assess risk factors and biomarkers for CRC or its survivorship will be conducted, ultimately providing research evidence from Chinese population and optimising evidence-based guidelines across the CRC continuum.

Keywords: gastrointestinal tumours, epidemiology, surgery

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The National Colorectal Cancer Cohort (NCRCC) is a prospective and observational design with large sample size and supports a wide range of research topics related to endpoints across colorectal cancer (CRC) continuum from the aetiology through survivorship.

We collected comprehensive exposure data and multidimensional clinical information as well as multiple biospecimens.

The Colorectal Cancer Patients’ Cohort (CRCPC) has large number of patients with CRC with geography diversity.

Some epidemiological data and specific biospecimen collection are not available in all research sites.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide.1 In China, the CRC incidence and mortality have rapidly increased in recent years.2 3 In parallel, the number of CRC survivors continues to increase, which is partly due to wider participation in CRC screening and personalised comprehensive treatment.4–6 Therefore, recognising that prognosis in cancer survivors has tremendous associations with early diagnosis, treatment and health behaviours, evidence-based guidelines are urgently required to improve these processes.

Studies of lifestyle factors, genetic and molecular profiles can contribute to discovery of novel and powerful predictors of early screening, clinical outcomes and survival. However, such studies require large sample size with comprehensive exposure data, well-annotated clinical outcomes, multiple types of biospecimens and high-quality follow-up information. Compared with the well-known established CRC cohorts, there are few large prospective cohorts that combine a comprehensive set of behavioural factors, together with detailed assessments of clinical outcomes and survivorship endpoints in survivors. Additionally, all those established CRC patient cohorts provided sample size with less than 10 000 and the study populations were restricted in developed countries.7 8 However, patterns of exposure vary markedly between developed countries and developing countries, especially in diet and lifestyle. Therefore, there is a critical need for a large CRC cohort capable of identifying potentially modifiable factors and novel biomarkers for screening and clinical outcomes, and assessing survivorship related to CRC treatments, especially in developing countries.

With an unprecedented economic development in recent years, the whole landscape of lifestyle behaviours in Chinese population has been largely changed. Resent researches have shown that the increasing CRC incidence and mortality were mainly due to unhealthy lifestyle changes, such as obesity,9 Western dietary habits,10 11 insufficient exercise,10 smoking12 and excessive alcohol drinking.13 However, to date, still little is known about the effects of changed lifestyle on incidence and prognosis of CRC among the Chinese population. Meanwhile, existing diagnosis and treatment guidelines of CRC have limited research evidence from the Chinese population, and the clinical outcomes of comprehensive treatments to CRC in developing countries require further verification by large cohort studies. Therefore, it is desirable to develop a cohort with large sample size in China to support a series of well-powered studies and provide evidence to improve guidelines of CRC screening, diagnosis, treatment and management for the Chinese population.

Research questions

The National Colorectal Cancer Cohort (NCRCC) study aims to recruit patients with CRC and individuals who have one or more high-risk factors of CRC. It was developed specifically to support valuable studies involving aetiological analysis, early screening and diagnosis, clinical outcomes and survivorship in well-characterised Chinese population. Specific research purposes and contents of the NCRCC study were:

(1) To integratively investigate lifestyle and genetic risk factors for CRC to develop risk prediction models.

We will assess the specific exposure spectrum in Chinese population, such as diet, alcohol drinking, smoking, physical activity, body fatness and aspirin use and investigate the association between these lifestyle factors and the risk of CRC. Single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping will be conducted to estimate the association between genetic variants and CRC risk. Since CRC is a complex disease that results from both genetic and lifestyle factors,14 15 interactions between lifestyle factors and genetic variants will also be evaluated. Finally, lifestyle and genetic risk factors will be combined to develop risk prediction models.

(2) To discover and validate new biomarkers for early screening and diagnosis, and prognosis.

We will identify new biomarkers (eg, metagenomic, metabolomic, genetic, epigenetic and proteomic biomarkers) for early screening and diagnosis. Previous studies have shown that gut microbiota contribute to the development of CRC16 and have potential to be biomarkers for CRC and adenoma diagnosis.17 18 At the present stage, we mainly focus on gut microbiota and their metabolites. For example, circulating bacterial DNA has been reported to discriminate other cancers (eg, prostate cancer and lung cancer) from healthy controls; however, it remains unexplored in patients with CRC. We will characterise alterations of bacterial DNA and their metabolites in plasma samples and identify bacteria-related biomarkers for CRC early detection as well as prognosis.

(3) To study the treatment response and survival disparities among patients and identify contributors to the observed disparities.

We will assess the treatment response of different therapies, such as neoadjuvant therapy, immunotherapy and identify the impact factors or applicable indicators of these therapies. For example, the gut microbiota and immune-related markers associated with the response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy will be studied. In addition, the association of surgical treatments (eg, complete mesocolic excision) and related operations with survival will also be investigated.

(4) To provide evidence-based recommendations for lifestyle behaviour changes to reduce the risk of CRC recurrence and therapy-induced adverse effect and improve the quality of life in survivors.

We will assess the lifestyle behaviour including diet, physical activity and medication use (eg, aspirin, statins and metformin) by questionnaires at diagnosis and during the following years and estimate the association between these modifiable factors and the risk of CRC recurrence among cancer survivors. Additionally, many patients with CRC who received treatments (eg, chemoradiotherapy) suffer from short and long-term adverse effects (eg, second primary cancer).19 Therefore, in this section, we will also focus on the impact of lifestyle behaviours on late effect of treatment and provide evidence for healthy lifestyle recommendation to improve the quality of life in survivors.

Cohort description

The NCRCC study includes two subcohorts: the Colorectal Cancer Screening Cohort (CRCSC), which is a community-based cohort recruiting participants who are identified as individuals at high risk of CRC and subsequently perform colonoscopy examinations, and the Colorectal Cancer Patients Cohort (CRCPC), in which newly diagnosed patients with CRC are recruited.

Colorectal Cancer Screening Cohort

The CRCSC was first launched in Jiashan County, Zhejiang Province, by the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, in January 2016. All individuals aged 40–74 years old who were permanent residents of Jiashan County and without history of CRC were eligible for CRC screening. The details of the screening were described in our previous study.20 Briefly, individuals were interviewed with a high-risk factor questionnaire (HRFQ) and submitted two faecal samples for faecal immunochemical tests (FITs). Those with a history of colorectal polyps or cancers other than CRC, or family history of CRC, or two or more of the following items: (1) chronic diarrhoea, (2) chronic constipation, (3) stressful life events, (4) mucous bloody stool, (5) chronic appendicitis or history of appendectomy, (6) chronic cholecystitis or history of cholecystectomy were regarded as positive HRFQ. A qualitative kit with a detection threshold of 100 ng haemoglobin/mL buffer was used for the FIT test. Individuals with a positive HRFQ result or at least one positive FIT result were identified as high-risk individuals and advised to perform a free colonoscopy examination. Those high-risk individuals who underwent a screening colonoscopy were recruited in CRCSC and were interviewed with a detailed baseline questionnaire by trained interviewers. By June 2020, 19 377 participants were enrolled. The demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in table 1. The average age of participants at enrolment was 58±8.3 years. Forty-eight percent of participants were men. The majority (94.4%) of participants received less than a high or technical school education.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants at enrolment in NCRCC study.

| Characteristics | CRCSC | CRCPC |

| N=19 377 (%) | N=15 551 (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 48.2 | 61.4 |

| Women | 51.8 | 38.6 |

| Age (year) | 58.7±8.3 | 60.3±12.3 |

| <50 | 15.1 | 18.9 |

| 50–65 | 56.8 | 42.9 |

| ≥65 | 28.1 | 38.2 |

| Education | ||

| No formal education | 30.4 | 21.8 |

| Elementary | 33.2 | 26.3 |

| Middle school | 30.7 | 25.0 |

| High/technical school | 4.7 | 12.9 |

| College or above | 1.0 | 14.0 |

| Family history of cancer | 29.9 | 26.6 |

| BMI(kg/m2) | 23.4±3.1 | 23.2±3.3 |

| Normal weight (18.5–24) | 55.39 | 53.8 |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 4.4 | 6.9 |

| Overweight (24–27.9) | 33.2 | 31.8 |

| Obesity(≥28) | 7.1 | 7.5 |

CRCPC, Colorectal Cancer Patients Cohort; CRCSC, Colorectal Cancer Screening Cohort; NCRCC, National Colorectal Cancer Cohort.

Colorectal Cancer Patients Cohort

Colorectal Cancer Patients Cohort (CRCPC) was a national, multicentre prospective cohort study, which was initiated in January 2015 and established at 16 hospitals (online supplemental table S1) from 11 provinces in China. All consecutive patients who were newly diagnosed with CRC and ascertained by histopathology were eligible for the study. Patients with a history of CRC or any mental condition that makes it impossible to provide informed consent or complete questionnaires were excluded. Each subject in the CRCPC was interviewed by a trained general physician or nurse in the local region. A baseline questionnaire was administered and the structured data of clinical information were abstracted from the electronic medical record (EMR). Standardised recruitment protocols were implemented at each research site. As of June 2020, 15 551 participants were enrolled in the CRCPC. The majority (61.4%) of participants were men, and 18.9% were under 50 years of age (table 1). A total of 73.1% received less than a high or technical school education.

bmjopen-2021-051397supp001.pdf (16.6KB, pdf)

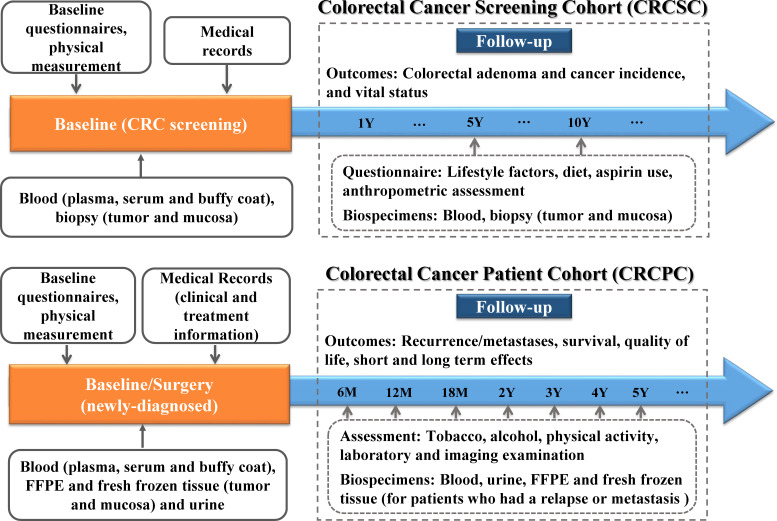

The study had been registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov. Detailed data and biospecimen collection procedures of the study are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of data and biospecimen collection for CRCSC and CRCPC in NCRCC study. CRCPC, Colorectal Cancer Patients Cohort; CRCSC, Colorectal Cancer Screening Cohort; FFPE, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; NCRCC, National Colorectal Cancer Cohort.

How often have been followed up?

CRCSC

Participants in the CRCSC were followed up by a combination of periodic CRC screening and linkage with regional or national cancer and death registry systems, and the follow-up would last for at least 10 years. The new CRC cases were identified by annually checking the files of cancer registry system, which included information on cancer location, histology and diagnosis date. The information on vital status was updated annually via the death registry system. In addition, each subject enrolled in the cohort would update their exposure and health status every 5 years during periodic CRC screening.

CRCPC

Follow-up for the CRCPC was conducted with both active and passive approaches and would last for at least 5 years. Participants were requested to come back to the hospital to check the health status at 6, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48 and 60 months after surgery. For patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy or (and) radiotherapy, reviews of medical records and exposure assessment were also performed at the end of each cycle. The research centres collected information on updated health status and behaviours and related specimens, including blood and urine samples. Computer matches with the cohort follow-up files identified patients who have presented for a recent appointment versus those who have not visited during each follow-up period. For the latter group, a phone call was sent to interview about the patient’s health status and lifestyle behaviours. CRC recurrence/metastasis was ascertained by carefully reviewing the patient’s medical record, including pathology and imaging reports. For patients who had not regularly visited the recruiting hospital during the follow-up period and shown any signs of cancer recurrence or metastasis, a review of outside medical records would be performed. Finally, for those lost to follow-up with the above two approaches, information on vital status was retrieved by linkage with a vital registration system.

What has been measured?

An NCRCC information system was developed to jointly record baseline data, clinical outcomes, follow-up data and biospecimen information and provide a platform for sharing data resources. Baseline data from the electronic questionnaire can be interconnected and submitted to the information system through the internet. Clinical outcomes of all participants were abstracted in a standardised form and submitted to the system. Biospecimens were stored at each research site but with centralised management of biospecimen information by the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University.

Data collection

A summary of the information collected in the NCRCC study is presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline, clinical and follow-up information collected in the NCRCC study

| Cohort | Measurements | |

| Baseline information | CRCSC, CRCPC | Demographic (eg, gender, education, marital status and race), family history of cancer, medical history, lifestyle factors (eg, tobacco and alcohol use history, physical activity, shift work, and sleep), diet (vegetables, red meat, white meat, fruit, soy food, milk, et al), medication use (eg, aspirin, statins, metformin, antibiotics), dietary supplement use (multivitamins, calcium), and for women, hormone replacement therapy, menopausal status, menstrual and reproductive history. Body weight, height, waist and hip circumference. |

| Clinical outcome | CRCSC | Diagnosis date, results of FIT and colonoscopy (number, location, size), pathological features and treatment. |

| CRCPC | Diagnosis date, AJCC stage, tumour location, pathological features (eg, histology, cell differentiation, lymphovascular or perineural invasion and number of positive lymph nodes), molecular features (MSI, KRAS, BRAF), imaging report (CT, colonoscopy), results of laboratory (CEA, CA199, et al), information on surgical procedures, surgical complications, treatment (ingredient, modality, timing and dose), tumour response and toxicities. | |

| Follow-up data | CRCSC | Lifestyle factors (eg, tobacco and alcohol use history, physical activity, shift work, and sleep), diet, medication use (eg, aspirin, statins, metformin, antibiotics), dietary supplement use (multivitamins, calcium), patients’ health (diagnosis of colorectal cancer) and vital status (survivorship, date and cause of death). |

| CRCPC | Lifestyle factors (tobacco and alcohol use, physical activity), patients’ health (recurrence/metastasis, treatment hospital, diagnosis of second primary cancer) and vital status (survivorship, date and cause of death) |

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; CA199, carbohydrate antigen 19; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CRCPC, Colorectal Cancer Patients Cohort; CRCSC, Colorectal Cancer Screening Cohort; FIT, faecal immunochemical test; MSI, microsatellite instability.

Baseline information

In the CRCSC, each individual was administered an electronic baseline questionnaire at recruitment. Items included demographics, lifestyle factors, diet, medication and dietary supplements use; for women, information on hormone replacement therapy, menopausal status and menstrual and reproductive history were also collected (table 2).

In the CRCPC, as part of the institutional registration process, all newly diagnosed patients were interviewed before treatment to complete baseline questionnaires, which include information on demographics (eg, gender, education, marital status and race), medical history, family history and medication use (eg, aspirin, statins, metformin). Since July 2018, an electronic questionnaire with more comprehensive baseline information (table 2) was first implemented at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University and would be gradually implemented at the remaining research sites. As of June 2020, 2122 records were collected using this tool.

For both cohorts, some specific exposures of Chinese populations, such as yellow rice wine, Chinese tea and diet, were investigated. Body weight, height, waist and hip circumference were measured by trained researchers at recruitment in both cohorts.

Clinical outcomes

In the CRCSC, for participants who had FIT or colonoscopy examination, the results of FIT or colonoscopy were collected. For participants with colorectal lesions after screening, information on pathological features and the following treatment were collected (table 2). In the CRCPC, detailed information on clinical outcomes was standardised and abstracted from the EMR (table 2).

Follow-up data

In the CRCSC, the diagnosis of CRC and vital status were collected through cancer and death registry systems. Detailed information on exposure, including lifestyle factors, diet, medication and dietary supplements, would be updated at periodic CRC screening (table 2).

In the CRCPC, information on lifestyle factors (eg, tobacco and alcohol use, physical activity), patients’ health (recurrence/metastasis, treatment hospital, diagnosis of second primary cancer) and vital status was collected at each follow-up.

Furthermore, we plan to collect more epidemiological data (eg, diet, medication and dietary supplement use) during the follow-up period to explore the association between postdiagnosis lifestyle behaviours and survival. In addition, data on quality of life (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-C30)21 are taken into consideration in 2020.

Biospecimen collection

Biospecimens, including blood and tissue samples, were collected, processed and stored according to the same standardised protocols at all research sites. In the CRCSC, each subject provided two 5 mL blood samples at recruitment. Biopsy tissue samples, which included polyp or tumour tissue and normal mucosa, were collected from participants who had lesions. In the CRCPC, newly recruited participants provided two 5 mL blood samples before treatment and immediately after surgery, respectively. All blood samples were kept at 4 °C, processed into plasma, serum and buffy coat within 6 hours and stored at −80 °C. Tissue samples that included tumour tissue and normal mucosa (both adjacent and distant to the tumour) were collected as both formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) and fresh frozen status. Fresh frozen tissue samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen after excision and delivered to be stored at −80 °C within 30 min to minimise the loss of RNA quality.22 For patients who had a relapse or metastasis and were treated in the recruiting hospital during the follow-up period, tissue samples were collected. In addition, 5 mL blood and urine samples at each clinic visit during follow-up period were collected in the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University.

Biospecimen collection rates differed by sample type, time point and research centre. In the CRCSC, more than 80% of participants had blood samples. In the CRCPC, blood samples at baseline are currently available for 62.5% of participants. Fresh frozen tissues were collected from approximately 30% of patients with CRC undergoing surgery, while FFPE tissues were generally available.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the development of this study.

Findings to date

Until June 2020, nearly 35 000 participants have been enrolled in the NCRCC study, with 19 377 participants in the CRCSC and 15 551 patients in the CRCPC. The demographic and selected baseline characteristics of the recruited NCRCC participants are shown in tables 1 and 3. Some selected clinical characteristics of CRCPC participants are given in table 4.

Table 3.

Selected baseline characteristics of participants at enrolment in NCRCC study

| Selected characteristics | CRCSC | CRCPC |

| N=19 377 (%) | N=2122* (%) | |

| Income (Yuan per year) | ||

| Less than 32 000 | 60.8 | 38.8 |

| 32 000~50 000 | 26.4 | 33.7 |

| More than 50 000 | 12.7 | 27.5 |

| WHR (mean±SD) | 0.91±0.05 | 0.92±0.06 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 85.1±8.1 | 81.0±8.8 |

| Tobacco | ||

| Ever smoked | 3.6 | 16.6 |

| Currently smoking | 28.2 | 24.1 |

| 1–14 cigarettes per day | 27.5 | 35.3 |

| 15–20 cigarettes per day | 57.8 | 55.6 |

| >20 cigarettes per day | 14.7 | 9.0 |

| Pack-years of smoking (mean±SD) | 34.2±18.1 | 31.1±19.2 |

| Alcohol | ||

| Ever drank | 1.5 | 10.8 |

| Currently drinking | 20.4 | 23.8 |

| Low risk drinking† | 30.3 | 44.9 |

| Medium risk drinking‡ | 28.1 | 21.1 |

| High risk drinking§ | 27.7 | 15.0 |

| Very high risk drinking¶ | 14.0 | 19.0 |

| Green tea | ||

| Former drinking | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Currently drinking | 33.6 | 26.6 |

| Red meat intake (≥4 times per week) | 51.9 | 39.2 |

| Vegetable intake (≥6 times per week) | 94.5 | 19.5 |

| Fruit intake (≥4 times per week) | 25.0 | 28.0 |

| Regular exercise | 13.4 | 34.1 |

| Sleep time (hour, mean±SD) | 8.4±1.2 | 8.7±1.0 |

| Aspirin use | 4.9 | 4.5 |

| Statin use | – | 4.7 |

| Metformin use | – | 4.1 |

| Hypertension | 34.8 | 35.8 |

| Diabetes | 7.6 | 12.1 |

| Vascular disease | 5.8 | 7.4 |

*2122 participants who received an electronic version questionnaire.

†40 g of alcohol consumption per day or less for men and 20 g for women.

‡41–60 g of alcohol consumption per day for men and 21–40 g for women.

§61–100 g of alcohol consumption per day for men and 41–60 g for women.

¶More than 100 g of alcohol consumption per day for men and 60 g for women.

CRCPC, Colorectal Cancer Patients Cohort; CRCSC, Colorectal Cancer Screening Cohort; NCRCC, National Colorectal Cancer Cohort; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.;

Table 4.

Selected clinical characteristics of colorectal cancer patients in the CRCPC

| Selected clinical characteristics | CRCPC |

| N=15 551 (%) | |

| Tumour site | |

| Colon | 46.3 |

| Rectum | 52.3 |

| Synchronous | 1.4 |

| AJCC stage | |

| Ⅰ | 16.4 |

| Ⅱ | 34.9 |

| Ⅲ | 34.5 |

| Ⅳ | 14.20 |

| Cell differentiation | |

| Undifferentiation/poor differentiation | 18.4 |

| Moderate differentiation | 9.2 |

| High differentiation | 72.4 |

| Histology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 94.7 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 4.4 |

| Signet-ring cell carcinoma | 0.5 |

| Carcinoid/neuroendocrine carcinoma | 0.3 |

| CEA | |

| <5 µg/L | 37.0 |

| ≥5 µg/L | 63.0 |

| CA199 | |

| <37 µg/L | 9.4 |

| ≥37 µg/L | 90.6 |

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; CA199, carbohydrate antigen 199; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CRCPC, Colorectal Cancer Patients Cohort.

In the CRCSC, the prevalence of overweight/obesity (BMI ≥24 kg/m2) was 40.3%, and that of obesity (BMI ≥28 kg/m2) was 7.1%. A total of 3.6% patients had ever smoked and 28.2% currently smoked. Among the smokers, 14.7% smoked more than 20 cigarettes per day, and the average pack-years of smoking was 34.2±18.1 years. A total of 1.5% and 20.4% of participants reported having ever drunk and currently drinking alcohol, respectively. Among the drinkers, 14.0% were very high-risk drinkers (more than 100 g of alcohol consumption per day for men and 60 g for women).23 A total of 33.8% of participants had ever drunk/currently drank Chinese tea and 13.4% engaged in regular exercise. At the baseline survey, 34.8%, 7.6% and 5.8% of the participants reported a history of hypertension, diabetes and vascular disease, respectively.

In the CRCPC, 16.6% had ever smoked, and 24.1% currently smoked. Among the smokers, 9.0% smoked more than 20 cigarettes per day, and the average pack-years of smoking was 31.1±19.2 years. A total of 10.8% had ever drunk and 23.8% currently drank regularly. Among the drinkers, 19.0% had very high-risk drinking. At the baseline survey, 35.8%, 12.1% and 7.4% of the participants reported a history of hypertension, diabetes and vascular disease, respectively. The percentages of rectal cancer and colon cancer were 46.3% and 52.3%, respectively. Of all the patients with CRC, 16.4% were at stage Ⅰ, 34.9% were at stage Ⅱ, 34.5% were at stage Ⅲ and 14.2% were at stage Ⅳ. The majority of pathology type was adenocarcinoma (94.7%), and 18.4% of patients were undifferentiated or poorly differentiated in tumour cells. A total of 37.0% and 9.4% of patients had carcinoembryonic antigen levels ≥5 µg /L and carbohydrate antigen 199 levels ≥37 µg/L, respectively.

Based on the NCRCC study, we conducted a substudy, which included 30 sporadic patients with CRC and 14 patients with colorectal adenoma from NCRCC. In this substudy, we have characterised alterations of bacterial DNA in plasma and identified 28 bacterial species with high predictive ability in preliminary discrimination between colorectal adenoma/cancer and healthy controls, demonstrating that circulating bacterial DNA has the potential to be used as a non-invasive tool for colorectal neoplasia screening and early diagnosis.24 In addition, associations of lifestyle factors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, diet intake and aspirin use, with colorectal neoplasia have been explored.

Strengths and limitations

The unique strength of the NCRCC study includes many aspects: prospective and observational design, large population with geographic diversity, richness in epidemiological and clinical data, multiple biospecimens and follow-up strategies. The goal of the NCRCC study is using these strengths to specifically assess risk factors and biomarkers related to endpoints across the CRC continuum from the aetiology through survivorship.

The NCRCC study design allows for the comprehensive assessment of multiple factors related to CRC incidence, treatment, prognosis and survival, which has rarely been studied among Chinese population. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, this large-scale national study (CRCPC), which includes 16 hospitals that are widely distributed in eastern, western, northern, southern and central China and has patients from almost all part of the country, is the largest CRC patient cohort with largest number of collaborating centres in China. Therefore, the results from the CRCPC may be generalisable to the whole patients with CRC in China.

The study is also strengthened by access to the EMR system to abstract multidimensional data (clinical, laboratory and imaging data) as well as the collection of comprehensive epidemiology data (dietary intake, lifestyle factors and medication use) at enrolment, which has not been available for most existing CRC patient cohort studies. Meanwhile, some exposure factors that are specific to the Chinese population offer a unique opportunity to better understand aetiology and prognosis of CRC. In addition, blood and tissue samples were collected from most participants, providing valuable resources to assess molecular biomarkers by multiomics. A series of blood and urine samples in posttreatment periods were also collected, enabling the assessment of changes in biomarkers in prognosis. Of note, the CRCPC is one of few existing CRC patient cohorts with a large number of biospecimens.

However, there are several limitations to this study. First, the CRCPC is a multicentre study that may introduce heterogeneity in participant enrolment, sample collection and follow-up. However, several standardised protocols for the study have been established and strictly enforced at each research site. All the data are standardised and uploaded through the internet from each research site. Second, epidemiological data and specific biospecimen collection are not sufficient. In our cohort, some epidemiological factors (eg, lifestyle factors, dietary intake and dietary supplement use) and samples (eg, urine) are not available in all research sites. However, these limitations will be eliminated by our ongoing efforts to collect the above-mentioned data from the remaining participants of the cohort.

In conclusion, the NCRCC study provides a large database and biorepository to test a wide range of scientific hypotheses related to CRC in the era of precision prevention, prediction and treatment. In addition, investigation of the association between specific exposure patterns in China with the development and prognosis of CRC will provide evidence-based guidance of health behaviours for Chinese population. Together, future findings of the NCRCC study will provide research evidence from Chinese population and optimise evidence-based guidelines across the CRC continuum.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely acknowledge Prof Zuo-Feng Zhang for his contributions to the study design. The authors would like to especially thank all NCRCC participants as well as staffs in the following hospitals and research centres who have made substantial contributions to the establishment of the National Colorectal Cancer Cohort: Beijing Cancer Hospital (Beijing), Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing), Cancer Institute of Jiashan (Zhejiang), Changhai Hospital (Shanghai), Daping Hospital, Third Military Medical University (Chongqing), Fujian Provincial Cancer Hospital (Fuzhou, Fujian), Hubei Cancer Hospital (Wuhan, Hubei), Jiangsu Provincial People's Hospital (Nanjing, Jiangsu), Peking University People's Hospital (Beijing), Shanxi Provincial Cancer Hospital (Taiyuan, Shanxi), Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (Guangzhou, Guangdong), The Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Hangzhou, Zhejiang), The Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University (Guangzhou, Guangdong), West China Hospital (Chengdu, Sichuan), Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University (Xi’an, Shaanxi), Zhejiang Academy of Medical Sciences (Hangzhou, China), Zhejiang Cancer Hospital (Hangzhou, Zhejiang), Zhongshan Hospital Fudan University (Shanghai).

Footnotes

YZ, YH and XK contributed equally.

Collaborators: The NCRCC introduction, progress, publication and contact information can be found at http://www.ncrcc.org.cn. Currently, the data are not yet openly available. Requests for potential collaboration can be addressed to Dr Kefeng Ding [dingkefeng@zju.edu.cn].

Contributors: YZ made substantial contributions to the conception of the study and drafted the manuscript. YH, XK and QX made contributions to the conception of the study and interpretation of data. ZP, ZZ, YW, ZW, DW and JC made contributions to the design of the study and data collection. KC, SZ, MW and XW made contributions to the design of the study and interpretation of data. KD made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. All authors have revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content and approved the final manuscript. KD acted as guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC0908200).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data are available upon reasonable request. Interested researchers can submit project proposals and request data or samples by contacting dingkefeng@zju.edu.cn. Ethics approval will be necessary prior to obtaining data.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for the NCRCC study was granted by the Committee on Research involving Human Subjects of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University (2017-072). Written informed consent was provided by each participant.

References

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:115–32. 10.3322/caac.21338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhu J, Tan Z, Hollis-Hansen K, et al. Epidemiological trends in colorectal cancer in China: an ecological study. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:235–43. 10.1007/s10620-016-4362-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:363–85. 10.3322/caac.21565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Levin TR, Corley DA, Jensen CD, et al. Effects of organized colorectal cancer screening on cancer incidence and mortality in a large community-based population. Gastroenterology 2018;155:1383–91. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee JK, Jensen CD, Levin TR, et al. Long-Term risk of colorectal cancer and related deaths after a colonoscopy with normal findings. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:153–60. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ulrich CM, Gigic B, Böhm J, et al. The ColoCare study: a paradigm of Transdisciplinary science in colorectal cancer outcomes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019;28:591–601. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wu X, Hildebrandt MA, Ye Y, et al. Cohort profile: the MD Anderson cancer patients and survivors cohort (MDA-CPSC). Int J Epidemiol 2016;45:713–713f. 10.1093/ije/dyv317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu P-H, Wu K, Ng K, et al. Association of obesity with risk of early-onset colorectal cancer among women. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:37–44. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Song M, Chan AT. The potential role of exercise and nutrition in harnessing the immune system to improve colorectal cancer survival. Gastroenterology 2018;155:596–600. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Song M, Chan AT, Diet CAT. Diet, gut microbiota, and colorectal cancer prevention: a review of potential mechanisms and promising targets for future research. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep 2017;13:429–39. 10.1007/s11888-017-0389-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gong J, Hutter CM, Newcomb PA, et al. Genome-Wide interaction analyses between genetic variants and alcohol consumption and smoking for risk of colorectal cancer. PLoS Genet 2016;12:e1006296. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rossi M, Jahanzaib Anwar M, Usman A. And alcohol Consumption-Populations to molecules. Cancers 2018;10:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huyghe JR, Bien SA, Harrison TA, et al. Discovery of common and rare genetic risk variants for colorectal cancer. Nat Genet 2019;51:76–87. 10.1038/s41588-018-0286-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johnson CM, Wei C, Ensor JE, et al. Meta-Analyses of colorectal cancer risk factors. Cancer Causes Control 2013;24:1207–22. 10.1007/s10552-013-0201-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Song M, Chan AT, Sun J. Influence of the gut microbiome, diet, and environment on risk of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2020;158:322–40. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.06.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shah MS, DeSantis TZ, Weinmaier T, et al. Leveraging sequence-based faecal microbial community survey data to identify a composite biomarker for colorectal cancer. Gut 2018;67:882–91. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liang JQ, Li T, Nakatsu G, et al. A novel faecal Lachnoclostridium marker for the non-invasive diagnosis of colorectal adenoma and cancer. Gut 2020;69:1248–57. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shin DW, Choi YJ, Kim HS, et al. Secondary breast, ovarian, and uterine cancers after colorectal cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Korea. Dis Colon Rectum 2018;61:1250–7. 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ye D, Huang Q, Li Q, et al. Comparative evaluation of preliminary screening methods for colorectal cancer in a mass program. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:2532–41. 10.1007/s10620-017-4648-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fayers P, Bottomley A, et al. , EORTC Quality of Life Group . Quality of life research within the EORTC-the EORTC QLQ-C30. European organisation for research and treatment of cancer. Eur J Cancer 2002;38 Suppl 4:S125–33. 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00448-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bray SE, Paulin FEM, Fong SC, et al. Gene expression in colorectal neoplasia: modifications induced by tissue ischaemic time and tissue handling protocol. Histopathology 2010;56:240–50. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03470.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization . International guide for monitoring alcohol consumption and related harm. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xiao Q, Lu W, Kong X, et al. Alterations of circulating bacterial DNA in colorectal cancer and adenoma: a proof-of-concept study. Cancer Lett 2021;499:201–8. 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-051397supp001.pdf (16.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data are available upon reasonable request. Interested researchers can submit project proposals and request data or samples by contacting dingkefeng@zju.edu.cn. Ethics approval will be necessary prior to obtaining data.