Abstract

The management of difficult-to-treat periocular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) becomes very challenging in cases of delayed diagnosis, leading to the development of locally advanced BCC. The aim of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of Hedgehog pathway inhibitors (vismodegib and sonidegib) treatment in patients affected by periocular locally advanced BCC. We focused on the common adverse events and their correlation with the administration schedule, to determine a management protocol specific for the periocular area.

This observational prospective study included a single-center case series with patients who were histologically confirmed to have periocular or orbital locally advanced BCC, treated with Hedgehog pathway inhibitors. All patients benefitted in terms of regression or stabilization of the neoplasm. In the first months of treatment, the HPIs were well tolerated, and the first important side effects appeared after about 5 months of continuous use of the drug.

These data could lead to a new type of therapeutic scheme where neoadjuvant therapy could be followed by pulse therapy as an adjuvant to surgery.

Key words: Skin cancer, Vismodegib, Sonidegib, Eyelid, Therapy

Introduction

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common malignancy in Caucasians and accounts for 75% of all skin cancers.1 Different risk factors are involved in the pathogenesis, and UV radiation is the most important cause. Therefore, sun-exposed areas such as the periocular area are very frequently involved. Among the various anatomical regions, the periocular region is certainly one of the most challenging sites for the appearance of a BCC because of its proximity to intracranial structures such as the eyes and to nerve endings. According to the literature, a low percentage of periocular BCCs (1.7% to 2.5%) can lead to the involvement of the orbital area.2,3

Factors that have been identified as leading risk factors for orbital involvement include male gender, advanced age, medial canthal location, previous recurrences, large tumor size, aggressive histologic subtype, and perineural invasion.4 In this particular location, perineural invasion is very frequent and is generally difficult to treat as it can present long after primary tumor removal. Furthermore, it can be associated with skip areas, which complicate margin control. It has been suggested that lowresistance cleavage planes and the perineural sheath can facilitate rapid and broad tumor extension.5 However, even in cases of small lesions, it is difficult for surgeons to maintain adequate safety margins without sacrificing important structures and leading to disfigurement. For these reasons, the current protocols used for the treatment of BCC should be adapted to the periocular location.

Surgery is generally the most efficient approach for easy-to-treat BCC, but it is not feasible for some complicated lesions, mostly due to possible disfigurement, loss of function, and the patient’s inability to endure the surgical procedure and reconstruction. Moreover, alternative therapies such as radiotherapy are not free of severe side effects, especially in this highly sensitive anatomical area. The management of difficult-to-treat lesions becomes very challenging in cases of delayed diagnosis, leading to the development of locally advanced BCC (laBCC). In laBCC, surgery or radiotherapy is no longer able to manage the lesion without important functional or aesthetic negative outcomes, or the patient is not eligible for or refuses surgery or radiotherapy. 6

The Hedgehog pathway inhibitors (HPIs) sonidegib and vismodegib are increasingly being used as a valid medical therapy in the management of laBCC. Several studies support the effectiveness and safety of these drugs.7-9

The aim of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of HPI treatment in patients affected by periocular laBCC at our center. We focused on the common adverse events (AEs) and their correlation with the administration schedule (continuous or alternative therapy) in order to determine a management protocol specific for the periocular area.

Materials and methods

This observational prospective study included patients who were histologically confirmed to have periocular or orbital laBCC and were treated with HPIs since January 2016 at the Department of Ophthalmology and Dermatology at the University of Florence, Italy.

The Local Institutional Review Board approved this observational study. Informed consent was obtained for each patient. The report adhere to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki as amended in 2013.

The inclusion criteria were lesions considered inoperable/inappropriate for surgery, previously administered radiotherapy unless inappropriate, and at least two cycles of HPI therapy having been already performed. One cycle of therapy is defined as 30 days and 28 days of treatment with sonidegib 200 mg once-daily and vismodegib150 mg once-daily, respectively.

The collected patient data included age, sex, BCC histotype, site, and extension. Orbital interest was confirmed by imaging (CT, MRI), which demonstrated bone and soft tissue involvement. Other data included the dose, duration, response to treatment, tolerability, and surgical treatment with histopathological findings. A complete response to treatment was defined as complete regression of the tumour. A partial response was defined as regression of tumour but not to the extent of a complete response. Patients received a follow-up visit monthly, and all AEs were recorded. Safety was evaluated by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 from the National Cancer Institute.10

Results

The study included 15 patients (8 females and 7 males), of which 13 were treated with vismodegib, and 2 treated with sonidegib. The mean age was 83 years (range 63-94 years, median 87 years). At presentation, 5 patients had orbital invasion. The primary location was the medial canthus for 8 patients, the lateral canthus for 6 patients, and the lower eyelid for one patient. The left eye was affected in 12 patients. Most patients had been previously treated with surgery-not eligible for radiotherapy (8/15; 53.33%); the others were patients previously treated with radiotherapy after surgery (2/15; 13.33%), or patients not eligible for surgery and radiotherapy (5/15; 33.33%) (Table 1).

Discontinued patients (n=9/15, 60%)

Three patients treated with vismodegib discontinued the drug upon complete response (CR) after an average drug intake of approximately 12 months. At 15 months after stopping therapy, one of these patients was still free from disease, but the other two patients had disease recurrence after 31 and 7 months of follow-up, respectively. One of these patients successfully underwent surgery, and the other resumed HPI therapy with an initial clinical response.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and exposure to HPI.

| Characteristics | Locally advanced BCC (N=15) |

|---|---|

| Median age-yr (range) | 87 (63-94) |

| Male sex, n. (%) | 7 (46.67) |

| Patients previously treated with surgery -not eligible for radiotherapy, n. (%) | 8 (53,33) |

| Patients previously treated with radiotherapy after surgery, n. (%) | 2 (13.33) |

| Patients not eligible for surgery and radiotherapy (%) | 5 (33,33) |

| Primary BCC site, n. (%) | |

| Medial canthus | 8 (53.33) |

| Later canthus | 6(40) |

| Lower eyelid | 1 (6.67) |

| BCC with orbital interest | 5 (33.33) |

| Discontinued patients (%) | 9(60) |

| CR | 3(20) |

| PR | 12(80) |

| Withdrawn for AEs | 5 (33.33) |

| Death for other causes | 1 (6.67) |

| Ongoing patients (%) | 6(40) |

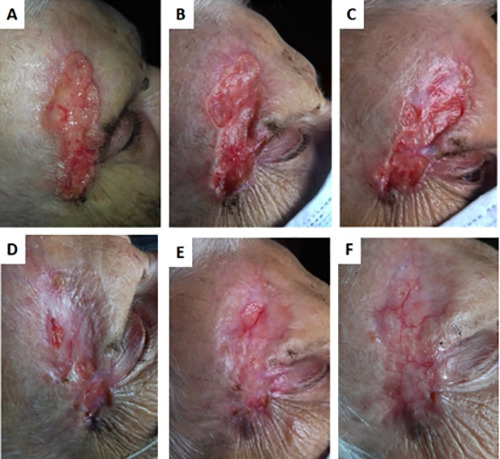

Figure 1.

Efficient re-epithelialization without exudate of a laBCC of the periocular and right frontotemporal regions upon therapy with 200 mg of daily sonidegib at baseline (A) and 1 month (B), 2 months (C), 3 months (D), 4 months (E), and 5 months (F) after start of treatment. Sonidegib 200 mg once daily was ongoing and very well tolerated except for a mild asthenia throughout the therapy that started at month 3.

One patient with a partial clinical response with vismodegib treatment died after 5 months of treatment from cancerindependent causes. Five patients who responded well to vismodegib therapy had to stop treatment due toAEs after approximately 5 cycles of treatment on average. The most frequent causes of interruption were dysgeusia with consequent weight loss and muscle spasms. In one case, the cause was liver toxicity. Of these 5 patients, 4 are currently in stable condition, and one patient progressed at about 3 months after the interruption. This latter patient is stable and has successfully undergone surgery.

Ongoing patients (n=6/15, 40%)

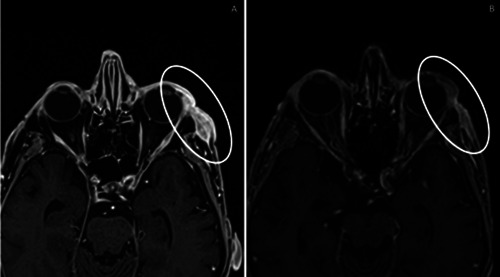

Two patients were being treated with sonidegib. One of these patients achieved a satisfactory response characterized by efficient re-epithelialization without exudate (Figure 1). Sonidegib treatment was very well tolerated with mild (grade 1) asthenia arising at 3 months after starting therapy. The second patient had previously been treated with multiple surgeries and reported to our center with a periocular and orbital lesion characterized by extensive infiltration of the lateral rectus muscle and lacrimal gland. Ongoing treatment with sonidegib at 200 mg daily led to a significant reduction of the extraorbital invasion after only 4 cycles (Figure 2). The patient experienced mild (grade 1) AEs, including muscle pain and CK elevation. During the first cycle, conjunctival chemosis affected the eye, but according to our ophthalmologist consultant, it was not related to sonidegib therapy. It resolved completely in 7 days with appropriate treatment and no reduction of the sonidegib dose.

Two patients are currently on an approved schedule treatment with vismodegib. They had a partial clinical response after 12 cycles on average. Both patients had dysgeusia and muscle spasms of low or medium severity. Another two patients treated with vismodegib underwent the first four months of continuous treatment according to the label, and then after a partial clinical response, they had to be administered an off-label alternative scheduledue to intolerable Aes. In particular, one patient presented with hypercreatininemia and takes the drug every other day with a maintained clinical response. The second patient suffered from major night cramps and continued therapy with vismodegib for 4 weeks on and 4 weeks off. The patient showed an improvement in Aes and maintained clinical response. In summary, all patients had clinical benefit in as early as the first two cycles of therapy (either complete or partial response or stable disease). The most common Aes were dysgeusia and muscle spasms (12 patients, 80%), followed by weight loss (7 patients, 46. 67%); fatigue (6 patients, 40%); anorexia, alopecia, and laboratory alteration (5 patients, 33.33%); nausea and constipation (2 patients, 13.33%); and diarrhea and mood alteration (1 patient, 6.67%) (Table 2)

Discussion

Among patients with BCC, the periocular region is certainly one of the most difficult anatomical sites to manage because of both its important functional aspect and the difficulty of having disease-free operating margins. In addition, the particular characteristics of the lesion (e.g., perineural invasion) combined with the multiple structures present at the periocular area favor a rapid spread to nearby and deep structures with serious damage to the patient. For these reasons, and according to our experience, protocols dedicated to the periocular area should be developed. The purpose of our study was to present our therapeutic management strategy for this particular anatomical site.

Figure 2.

Extraorbital invasion of the lateral rectus muscle at baseline (A) and significant reduction of the infiltration after 4 months on sonidegib at 200 mg daily (B).

Table 2.

Adverse events.*

| Adverse event | Locally advanced basal cell carcinoma (N=15) | |

|---|---|---|

| Any grade n. of patients (%) | Grade ≥3 n. of patients (%) | |

| Any° | 15(100) | 5 (33.33) |

| Led to discontinuation# | 5 (33.33) | 1 (6.67) |

| Dysgeusia | 12(80) | (0) |

| Muscle spasm | 12(80) | 4 (26.67) |

| Weight loss | 7 (46.67) | (0) |

| Fatigue | 6(40) | (0) |

| Anorexia | 5 (33.33) | (0) |

| Alopecia | 5 (33.33) | (0) |

| Laboratory alterations | 5 (33.33) | 1 (6.67) |

| Constipation | 2 (13.33) | (0) |

| Nausea | 2 (13.33) | (0) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (6.67) | (0) |

| Mood alteration | 1 (6.67) | (0) |

*The severity of adverse events was graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0. The events are listed in descending order of frequency in any grade. °Patients treated with sonidegib had no adverse events greater than G1.

#Adverse events leading to discontinuation: dysgeusia (4 patients), muscle spasms (2 patients), liver toxicity (1 patient). Some patients had more than one adverse event leading to discontinuation.

An important finding that of our study is that all patients benefitted in terms of regression or stabilization of the neoplasm. In this periocular site, our rates of complete responders (20%) and partial responders (80%) were higher than the values obtained in the skin in general.6,8 In our case series, the first evident clinical response to the drug was a fast onset in all patients with an average of about 2-3 months from the start of therapy.

In the first months of treatment, the HPIs were well tolerated, and the first important side effects appeared after about 5 months of continuous use of the drug. These side effects led 33.33% of patients to discontinue the drugs despite good clinical results. Two patients, however, were moved to an unapproved vismodegib treatment schedule adapted to their AEs after about 4 months of vismodegib therapy at the first appearance of AEs.

Sonidegib is an alternative to off-label vismodegib and is the only HPI with an approved alternate-day dose (200 mg every other day), which favors the use of sonidegib in the management of patients experiencing AEs.11 The adjustment of dose is tailored to the patient’s symptoms and has already been investigated in previous studies. These studies showedvery good outcomes in terms of therapy adherence, clinical response, and tolerability.12-14

According to the literature, dysgeusia and muscle spasm begin to appear after three months of therapy and often result in modification of the dosage until withdrawal. 15 In our experience, the impact of dysgeusia is heavier in older patients (the mean age for grade 2 dysgeusia was 86, while that for grade1 was 76.8). In contrast, muscle spasms were more severe in younger patients (the mean age was 77.71byears for grade 2 and 3 muscle spasms and 86.17 for grade 1)

Furthermore, two of our patients underwent a surgical re-evaluation and were declared operable. The interventions were successful with disease-free margins, and the patients are currently in follow-up without disease recurrence. A neoadjuvant approach with HPIs has already been reported previously.16-18 In this setting, the use of sonidegib may be of interest since AEs seem to appear slightly later than with vismodegib.6 This would provide suitable time to perform a neoadjuvant approach without significant tolerability issues. Additionally, the median time to response according to an investigator review was 2.5 months at the 42-month follow-up for sonidegib and 4.7 months at the 39-month analysis for vismodegib.7,8 Again, this places sonidegib in a good potential position in a neoadjuvant setting.

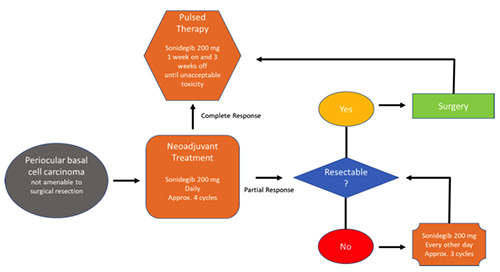

We propose a new regimen for periocular laBCC,which will need to be assessed in future studies. In this approach (Figure 3), periocular BCCs that are not amenable to surgery undergo approximately 4 cycles of neoadjuvant sonidegib at 200 mg daily [time to reach steady state (sonidegib SmPC)]. If this treatment leads to CR, a pulsed therapy can be applied (sonidegib 200 mg daily one week on and 3 weeks off) until unacceptable toxicity arises. Conversely, if there is partial response (PR) after the neoadjuvant approach and the lesion is resectable, the patient may undergo surgery and then pulsed therapy. If there is PR but the BCC cannot be excised, the patient may be put on the approved sonidegib dose of 200 mg every other day for approximately 3 cycles and then reassessed for resectability.

A direct comparison between vismodegib and sonidegib in a randomized controlled clinical trial is not available. Recently, a panel of European experts considered the ERIVANCE and BOLT trials appropriate for indirect comparison between sonidegib and vismodegib.6 At the 21-month follow-up, RECIST ORR for vismodegib was 47.6%, with 22.2% CR and 25.4% PR according to a central review. At the 18-month follow-up, the RECIST-like ORR of sonidegib was 60.6% with 21.2% CR and 39.4% PR according to a central review.6

Figure 3.

Periocular laBCC treatment algorithm proposed for future studies. Patients with periocular BCCs not amenable to surgery may undergo approximately 4 cycles of neoadjuvant sonidegib at 200 mg daily. If this treatment leads to CR, a pulsed therapy can be applied (sonidegib 200 mg daily one week on and 3 weeks off ) until unacceptable toxicity. If there is PR after neoadjuvant approach and the lesion is resectable, the patient may undergo surgery and then pulsed therapy.If there is PR but the BCC cannot be excised, the patient may be put on the approved sonidegib dose of 200 mg every other day for approximately 3 cycles and then re-assessed for resectability.

Additionally, the experts concluded that sonidegib had an approximately 10% lower incidence of most AEs and slightly less severe AEs compared with vismodegib. The time to onset of AEs also indicated that patients treated with sonidegib may experience AEs slightly later than those treated with vismodegib.6 Finally, differences in the pharmacokinetic profile suggest that sonidegib is more extensively distributed in the skin than vismodegib, which may explain the potential differences in efficacy and toxicity between them.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the possibility of an alternative schedule to the label, the potential as a valid neoadjuvant therapy, the lower incidence and severity, and the slower onset of most AEs seen in trials convinced us to gain more experience with sonidegib. However, several limitations of this case series need to be considered. First of all, our data are from a single center, which potentially limits the generalizability of our results. Moreover, the low number of lesions included and the non-comparative methodology limit the thorough evaluation of other possible predisposing factors.

Nevertheless, these data could lead to a new type of therapeutic scheme where neoadjuvant therapy could be followed by pulse therapy as an adjuvant to surgery. However, there are concerns that this scheme could have tolerability issues. This proposal must be validated by larger case studies and multicenter trials.

Funding Statement

Funding: None.

References

- 1.Peris K, Fargnoli MC, Garbe C, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guidelines. Eur J Cancer 2019;118:10-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howard GR, Nerad JA, Carter KD, Whitaker DC. Clinical characteristics associated with orbital invasion of cutaneous basal cell and squamous cell tumors of the eyelid. Am J Ophthalmol 1992;113:123-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong VA, Marshall JA, Whitehead KJ, et al. Management of periocular basal cell carcinoma with modified in face frozen section controlled excision. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;18:430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leibovitch I, McNab A, Sullivan T, et al. Orbitalinvasion by periocularbasalcell carcinoma. Ophthalmology 2005;112:717-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun MT, Wu A, Figueira E, et al. Management of periorbital basal cell carcinoma with orbital invasion. Future Oncol 2015;11:3003-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Sonidegib and vismodegib in the treatment of patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma: a joint expert opinion. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020;34:1944-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dummer R, Guminksi A, Gutzmer R, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of sonidegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma: 42-month analysis of the phase II randomized, doubleblind BOLT study. Br J Dermatol 2020;182:1369-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sekulic A, Migden MR, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of vismodegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma: final update of the pivotal ERIVANCE BCC study. BMC Cancer 2017;17:332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basset-Seguin N, Hauschild A, Kunstfeld R, et al. Vismodegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma: Primary analysis of STEVIE, an international, open-label trial. Eur J Cancer 2017;86:334-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). Rockville, MD: National Cancer Institute. Available from: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm. Updated March 1, 2018. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_5x7.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odomzo (sonidegib). Summary of Product Characteristics 2020. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/odomzo [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacouture ME, Dréno B, Ascierto PA, et al. Characterization and Management of Hedgehog Pathway Inhibitor-Related Adverse Events in Patients With Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma. Oncologist 2016;21:1218-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker LR, Aakhus AE, Reich HC, Lee PK. A Novel Alternate Dosing of Vismodegib for Treatment of Patients With Advanced Basal Cell Carcinomas. JAMA Dermatol 2017;153:321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woltsche N, Pichler N, Wolf I, et al. Managing adverse effects by dose reduction during routine treatment of locally advanced basal cell carcinoma with the hedgehog inhibitor vismodegib: a single centre experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019;33:e144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scalvenzi M, Villani A, Costa C, Cappello M. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in patients with basal cell carcinoma: An Italian Center experience. Dermatol Ther 2019;32:e12971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ally MS, Aasi S, Wysong A, et al. An investigator-initiated open-label clinical trial of vismodegib as a neoadjuvant to surgery for high-risk basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;71:904-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sagiv O, Nagarajan P, Ferrarotto R, et al. Ocular preservation with neoadjuvant vismodegib in patients with locally advanced periocular basal cell carcinoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2019;103:775-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monteiro AF, Rato M, Trigo M, Martins C. Aggressive Inferior Eyelid Basal Cell Carcinoma: Advantage of Neoadjuvant Vismodegib. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2019;110:863-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]