Abstract

This study examines rates of home dialysis and transplant at dialysis facilities that serve patients with high social risk to understand how they fare under the End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices Model.

In 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the mandatory End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices (ETC) Model, which randomly assigned 30% of dialysis facilities to receive financial incentives to increase home dialysis and kidney transplants. Social risk factors, such as exposure to poverty and racism, are associated with less access to home dialysis and kidney transplant, but the ETC Model performance measures did not initially account for social risk.1,2,3 We assessed rates of home dialysis and transplant among dialysis facilities that serve patients with high social risk to understand how these facilities may fare under the ETC Model.

Methods

We attributed adult patients with incident kidney failure from January 2017 through June 2020 to dialysis facilities using CMS Form 2728 (Supplement). Consistent with CMS methods, we aggregated facilities with common ownership (from Dialysis Facility Compare) within the same hospital referral region (hereafter referred to as facility groups). The ETC Model includes prevalent patients receiving dialysis enrolled in traditional Medicare. Our data included all incident patients receiving dialysis and lacked information on 1 ETC Model measure (transplant waitlisting).

Four measures of social risk identified facility groups in the highest quintile of the percentage of incident patients who were non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, uninsured or Medicaid-covered at dialysis initiation, or residents of neighborhoods in the highest quintile of disadvantage using the 2018 Area Deprivation Index (Supplement). A composite score assigned groups with none, 1, or at least 2 of these characteristics.

Two-tailed independent t tests compared home dialysis initiation and 1-year overall and living donor age-standardized kidney transplant by facility groups’ social risk scores. Beginning in 2022, CMS will stratify performance by groups’ share of patients who are dual-eligible or receive Medicare’s Low-Income Subsidy using a cut point of 50%.4 We approximated this stratification using facility groups’ share of Medicaid-covered patients, with the group mean (27.9%) as the cut point (Supplement). Analyses were conducted in Stata version 17 with a significance threshold of P < .05. Brown University’s institutional review board approved the study with a waiver of informed consent.

Results

We attributed 422 831 incident patients (177 031 [41.9%] women) at 7570 dialysis facilities to 1713 dialysis facility groups, of which 479 (28%) had 1 social risk characteristic and 410 (24%) had 2 or more (Table). Compared with facility groups with no social risk features, groups with 2 or more features were less likely to offer peritoneal dialysis (62.1% vs 79.5%; difference, −17.5 [95% CI, −12.1 to −22.8] percentage points) and had lower rates of home dialysis initiation (9.3% vs 15.6%; difference, −6.3 [95% CI, −3.8 to −8.9] percentage points) and 1-year transplant (1.7% vs 3.6%; difference, −1.9 [95% CI, −1.4 to −2.4] percentage points). Facility groups with 1 social risk feature had lower 1-year transplant rates but similar home dialysis initiation rates as facility groups with none.

Table. Characteristics of Dialysis Facility Groups, by Composite Social Risk Score, January 2017–June 2020.

| Characteristics | Composite social risk scorea | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | ≥2 | |

| Facility groups, No. (%)b | 824 (48.1) | 479 (28.0) | 410 (23.9) |

| Facilities per group, mean (SD) | 4.6 (7.3) | 4.7 (9.5) | 3.7 (7.7) |

| No. of incident patients per facility group, median (IQR) | 90 (35-276) | 79 (31-270) | 68 (32-159) |

| Incident patient composition at facility group level, mean (SD), % | |||

| Non-Hispanic Blackc | 14.0 (12.3) | 29.0 (24.8) | 39.1 (30.3) |

| Hispanicc | 7.0 (6.7) | 16.5 (18.5) | 29.4 (29.1) |

| With Medicaid/uninsured | 23.7 (9.3) | 31.3 (12.2) | 52.3 (17.8) |

| From high social disadvantage neighborhoodd | 15.9 (13.7) | 27.5 (22.8) | 34.0 (29.6) |

| Facility group characteristics, No. (%) | |||

| For-profit | 547 (70.4) | 359 (78.7) | 270 (71.6) |

| Chain | 472 (60.7) | 271 (59.4) | 159 (42.2) |

| ≥1 Facility with late shift | 324 (41.7) | 164 (36.0) | 128 (34.0) |

| ≥1 Facility offers hemodialysis | 742 (95.5) | 428 (93.9) | 367 (97.3) |

| ≥1 Facility offers peritoneal dialysis | 618 (79.5) | 351 (77.0) | 234 (62.1) |

| ≥1 Facility offers home hemodialysis | 461 (59.3) | 234 (51.3) | 139 (36.9) |

| Facility group assigned to ETC Model | 272 (33.0) | 140 (29.2) | 109 (26.6) |

| No. of dialysis stations per facility, mean (SD) | 14.8 (7.4) | 16.3 (9.3) | 18.2 (9.8) |

| Incident patient outcomes at facility group level, mean (SD), %e | |||

| Initiating with home dialysis | 15.6 (23.1) | 15.4 (24.4) [P = .89] | 9.3 (18.2) [P <.001] |

| With kidney transplant by 1 yf | 3.6 (4.6) | 2.3 (3.1) [P <.001] | 1.7 (3.3) [P <.001] |

| With living-donor kidney transplant by 1 yf | 1.9 (2.9) | 1.3 (2.4) [P <.001] | 0.9 (2.1) [P <.001] |

| Facility groups with performance measure rates of 0%, No. (%)e | |||

| Home dialysis rate of 0% | 201 (24.4) | 126 (26.3) [P = .44] | 185 (45.1) [P <.001] |

| 1-Year transplant rate of 0%f | 274 (33.3) | 189 (39.5) [P = .02] | 211 (51.5) [P <.001] |

| 1-Year living donor transplant rate of 0%f | 366 (44.4) | 244 (50.9) [P = .02] | 269 (65.6) [P <.001] |

Composite social risk score is the number of categories of social risk per facility group. Categories of social risk were facility groups in the highest quintile of proportion of incident patients who were non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, uninsured or Medicaid-covered at dialysis initiation (including those dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare), and residents of neighborhoods with high social disadvantage.

Facility groups are composed of all dialysis facilities with common ownership in a given hospital referral region.

Patient race and ethnicity were obtained from categories available on CMS Form 2728, completed by the dialysis facility’s attending physician, head nurse, or social worker for patients, with instructions to obtain patients’ self-reported ethnicity and race (included in the study as a proxy for the social risk factor of exposure to structural and/or interpersonal racism).

High social disadvantage neighborhoods were defined as those in the highest quintile of area deprivation using the 2018 Area Deprivation Index.

Two-tailed independent t tests were used to compare outcomes of facility groups with 1 or ≥2 vs those with 0 social risk characteristics.

Transplant rate includes only incident patients aged 18-74 years who initiated dialysis in January 2017–June 2019. Transplant rates were age-standardized to the overall distribution of attributed patients by age 18-55, 56-70, and 71-74 years, consistent with the End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices (ETC) Model and national standardized transplantation ratio metrics.

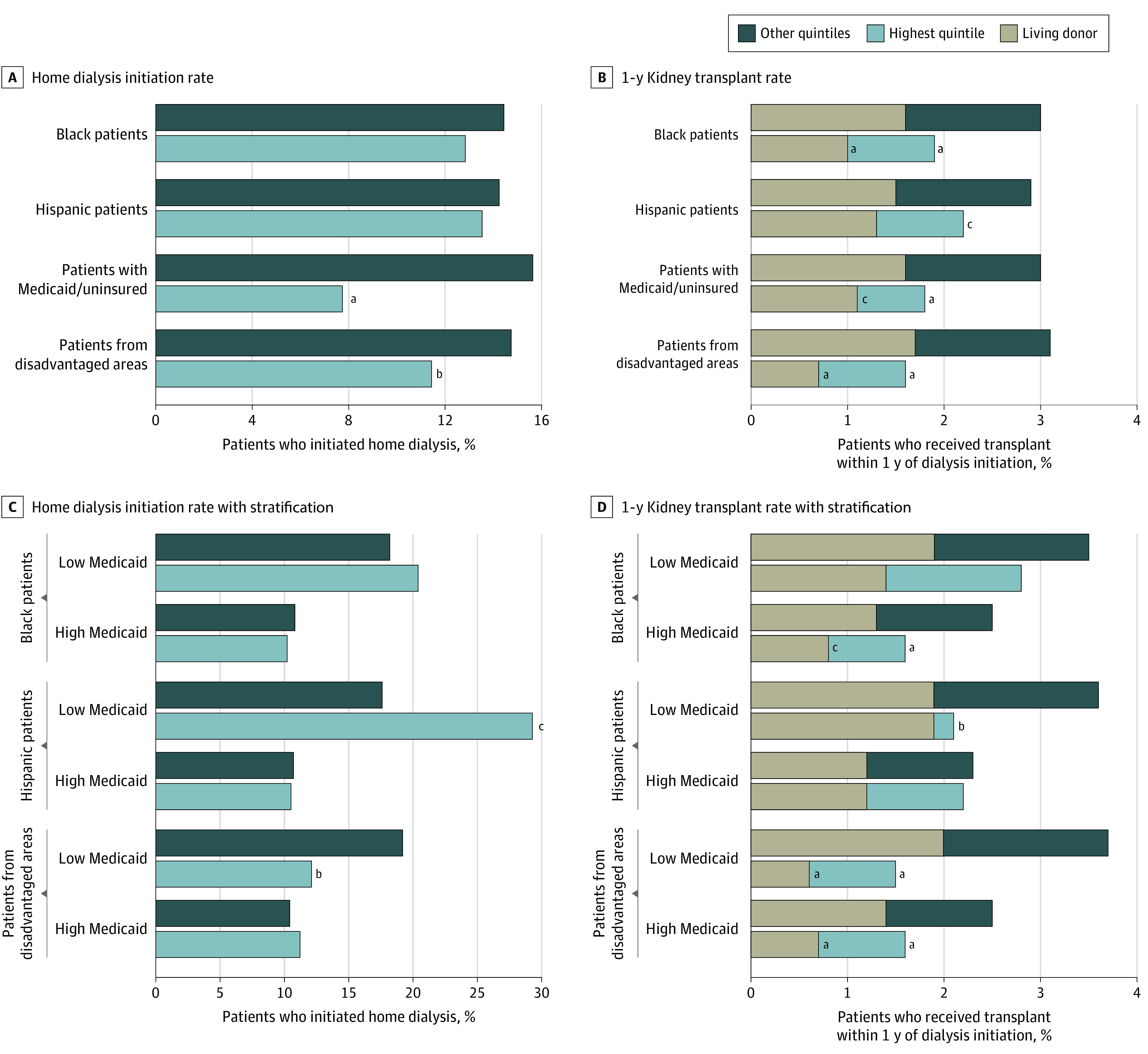

Facility groups in the highest quintile of uninsured/Medicaid-covered patients had lower home dialysis initiation (7.7% vs 15.6%; difference, −7.9 [95% CI, −5.3 to −10.6] percentage points), but comparisons stratified by share of Medicaid-covered patients mitigated differences. One-year transplants were significantly lower for facility groups with large percentages of non-Hispanic Black patients or patients from disadvantaged neighborhoods, and persisted after stratification by facility share of Medicaid-covered patients (Figure).

Figure. Home Dialysis Initiation and 1-Year Kidney Transplant Rates for Dialysis Facility Groups, by Dimension of Social Risk, January 2017–June 2020.

Facility groups are composed of all dialysis facilities with common ownership in a given hospital referral region. The characteristics of adult incident dialysis patients in January 2017–June 2020 were used to identify facility groups in the highest quintile of proportion of patients who were non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, uninsured or Medicaid-covered at dialysis initiation (including those dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare), and residents of the most socially disadvantaged neighborhoods. Age-standardized transplant rates include only incident patients aged 18 to 74 years who initiated dialysis from January 2017 through June 2019. Two-tailed independent t tests were used to compare outcomes of facility groups in the highest quintile vs other quintiles for each dimension of social risk. “Low-Medicaid” facility groups have fewer Medicaid-covered patients than the national mean of 27.9%; “high-Medicaid” groups have more Medicaid-covered patients than the national mean. This stratification is similar to the CMS’ forthcoming changes to the End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices Model.

aP < .001. bP < .05. cP < .01.

Discussion

Dialysis facility groups serving higher proportions of patients with social risk factors performed worse on measures similar to those in the ETC Model vs facility groups serving patients with fewer social risk factors. Less use of home dialysis and transplant may disproportionately penalize these facilities, consistent with other CMS alternative payment models.5,6 Stratifying performance by share of patients with Medicaid, consistent with CMS’ forthcoming policy, attenuated differences in home dialysis by social risk. However, differences in kidney transplant between facilities serving patients with higher vs lower social risk largely persisted.

Study limitations include the following differences from the ETC Model: using incident rather than prevalent patients, not restricting to traditional Medicare beneficiaries, and lack of data on transplant waitlisting.

The ETC Model includes both achievement and improvement pathways, so low-performing facilities may avoid penalties if they can improve home dialysis and transplant rates. However, facility groups that cared for patients with high social risk were less likely to offer home dialysis services. These findings support monitoring the effect of the ETC Model on facilities that provide care for underserved populations.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Associate Editor.

eMethods

eReferences

References

- 1.Arriola KJ. Race, racism, and access to renal transplantation among African Americans. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(1):30-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy KA, Jackson JW, Purnell TS, et al. Association of socioeconomic status and comorbidities with racial disparities during kidney transplant evaluation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(6):843-851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen JI, Chen L, Vangala S, et al. Socioeconomic factors and racial and ethnic differences in the initiation of home dialysis. Kidney Med. 2020;2(2):105-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medicare program; end-stage renal disease prospective payment system, payment for renal dialysis services furnished to individuals with acute kidney injury, end-stage renal disease quality incentive program, and end-stage renal disease treatment choices model. Federal Register. Published November 8, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2021. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/11/08/2021-23907/medicare-program-end-stage-renal-disease-prospective-payment-system-payment-for-renal-dialysis [PubMed]

- 5.Qi AC, Butler AM, Joynt Maddox KE. The role of social risk factors in dialysis facility ratings and penalties under a Medicare quality incentive program. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(7):1101-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joynt Maddox KE, Reidhead M, Hu J, et al. Adjusting for social risk factors impacts performance and penalties in the hospital readmissions reduction program. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(2):327-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eReferences