Abstract

The objective of this essay is to clarify the understanding and use of Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) by exploring basic characteristics of ‘determinants’ and ‘fundamental causes,’ the ‘social,’ ‘structure,’ and ‘modifiability,’ and to consider theoretical and practical implications of this reconceptualization for public health. The analysis distinguishes Social Determinants of Health from other determinants of health. We define social determinants of health as mutable societal systems, their components, and the social resources and hazards for health that societal systems control and distribute, allocate and withhold, and that, in turn, cause health consequences, including changes in the demographic distributions and trends of health. A systems conceptualization holds concepts such as “race” as the creations of social systems and as having negative consequences, such as racism, when part of a racist system, but potentially ameliorative consequences when part of an anti-racist system. The integration of Social Determinants of Health into public health theory and practice may substantially expand the benefits of public health, but will require new theorizing, intervention research, education, collaboration, policy, and practice.

Significance for public health.

Clarity in the conceptual and theoretical basis of SDOH creates critical opportunities for major advances in public health understanding and intervention. The questions raised here should continue to be reviewed and addressed. The refinement of concepts in public health serves to strengthen the tools of the discipline and further its goals, i.e., the understanding and improvement of the health of the public and the promotion of equitable access to societal resources for health for all.

Keywords: Social determinants of health, causation, methods, theory, race, systems, preventive measures

“Medicine is a social science, and politics nothing but medicine on a grand scale.”

Rudolph Virchow, 1848

While the power of social determinants of health (SDOH) has long been recognized,1-3 attention to SDOH in public health has grown rapidly in recent decades. Claims that specific phenomena are SDOH have proliferated.4-9 The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 (HR133) includes $3M for the CDC to create a SDOH Pilot Program to fund SDOH Accelerator Plans (https://www.taxpayer. net/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/H.R.133-JES_Division- H_Labor-HHS.pdf). Because heightened awareness of SDOH may offer new opportunities for understanding and action in public health, the definition underlying this concept merits reconsideration. Definitions such as the widely-cited WHO version, “…the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes. …the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life,” (italics added) do not tell us what is and what is not a SDOH. All “conditions”? What is it about conditions that makes them SDOH? Which “forces”? Are “influence” and “shaping” causation?

Through a series of questions (Table 1), we dissect and reassemble the concept of SDOH and briefly review several prominent definitions. We explore how we might segment the “upstream—downstream” metaphor from way-upstream sources, e.g., racism, to midstream SDOH, e.g., racist institutions and laws, all the way downstream to health events, e.g., morbidity and death, that are the consequence of racist institutions and laws.10 We consider how a systems approach allows that health outcomes may affect changes in upstream SDOH in feedback loops.

We address ten basic questions (Table 1).

1. What is a determinant? A determinant of something is a cause. The notion of causality in SDOH is not conceptually different from that linking cigarette smoking and lung cancer or SARSCoV- 2 virus infection and COVID-19 disease. Many analyses of SDOH describe the linkage with cautious verbs such as “influence” and “shape,” suggesting that the connection is less than causal. Caution is unnecessary and misleading. Typically, causality results from the interplay of several factors together responsible for whether the SDOH, cigarette smoking, or SARS-CoV-2 infection result in the associated outcomes in given instances. For none of these factors is the connection between determinant and outcome ‘deterministic,’ such that the outcome inevitably follows the exposure; causation is essentially probabilistic. Not all smokers die from their smoking, not all infected with the SARS-CoV-2 become sick with COVID-19, not all those lacking a high school education die prematurely because of their educational level. Causality exists nevertheless. Scientific investigation aims to reveal mechanisms of causal action for potential intervention. In the case of cigarette smoke, the question is, by what processes or sequence of events, does cigarette smoke get into the body and cause lung cancer? Similarly, in the case of SDOH, the question is, how do social relations and society become literally “embodied,” “incorporated,” and result in pathology?1 Whether particular components of a society are SDOHs or not are empirical questions.

It is critical to consider what kind of a “thing” a determinant is - physical object, concept, relationship, event, system, or something else. Can a bullet be a determinant, a cigarette, hatred, a law, a year of education? A bullet, a cigarette, a law are by themselves inert objects or, in the case of law, prescriptions. As the gun advocates argue, bullets don’t kill, people do; but this conceptualization is insufficient. It is societal systems that make a bullet more or less likely to be a determinant; a bullet in Canada, where gun control laws are strict, is different from a bullet in the United States, where laws are more permissive. A civil rights law by itself is a principle, a prescription. To be a determinant it must be integrated in a societal system that enacts it and enforces it.

Several hallmarks characterize a system, such as a clock, a body, a society, a nation. A system is a group of interacting or interrelated entities that form a unified whole. A system, surrounded and influenced by its environment, is described by its boundaries, structure and purpose and expressed in its functioning (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/System). Though a system may be affected by outside forces, the system generates a characteristic response to those forces. The moon circling the earth is a system, though its path is also affected to lesser degrees by the gravity of other bodies in our solar system. A determinant is a system phenomenon, a pattern of interaction between system elements that affects an outcome of interest.

2. What makes a determinant a social determinant? While the determinant component of SDOH refers to its consequences, the social component refers to what distinguishes SDOH from other kinds of determinants of health, to what creates and maintains them.11 What makes human behavior social is its engagement in a (social) system of interaction with other humans within (social) boundaries and within a (social) framework comprised of institutions, roles, and rules of behavior and a culture of values, symbols, and ideologies, including religion, science, and popular beliefs that shape and rationalize societal organization and rules. Humans engage in multiple such systems, e.g., families, neighborhoods, clubs, schools, work, cities, nations, etc., each of which can have frameworks that differ, but often overlap.

Human action is social regardless of the presence of other people. A person in a room or on a desert island behaves socially in that he or she acts in response to a social framework of institutions, roles, and rules of behavior and a culture of beliefs, values, and symbols. Many elements and products of social process are SDOH.

An example of a non-social DOH is the seasons, i.e., the annual change in the tilt of the earth’s axis, the resultant changes in solar radiation exposure, and the health effects of these changes (although the effects of seasons may have been altered by humanaffected climate change). Another example of a non-social DOH is geographic variation in soil composition, where the absence of natural iodine in some regions causes undernutrition, morbidity, and mortality; this environmental condition is a determinant of health, but not a social one. However, knowing this situation, the public health community has devised programs to counter this environmental deficiency by providing iodized salt. These programs are SDOH; they are elements of a global social system of public health in which research has developed and implemented a response to an environmental-nutritional problem.

Social determinants of health are societal systems, their components, and the social resources and hazards for health that societal systems control and distribute, allocate and withhold, such that the demographic distribution or trend of health outcomes is changed. Societal systems include governments, institutions and other organizations, regulations and processes. The resources and hazards for health that these systems control, allocate, withhold, and distribute include food/lack of food, shelter/unshelter, safety/danger, sanitation/unsanitation, civic participation, education, employment, financial and commercial institutions, law and justice, law enforcement, defense, transportation, health information/ dis-information, and health care. It is this overall system and array of resources and hazards that allows and constrains the preventive and risk behavior of groups and individuals that then affects their health.

The health consequences of SDOH—illness, injury, and death—are also SDOH. As the results of SDOH, they are themselves social (and biological, environmental, genetic, etc.) products. A person is diagnosed with a cancer, becomes depressed, loses sleep, eats less, etc. with further health consequences. Health events themselves commonly have substantial social and health consequences, e.g., family, work, and community disruption and adjustment. In addition, the responses to health conditions occur in a complex social environment of health care. Further and importantly, as the COVID-19 pandemic clearly illustrates,12 health events may affect upstream social determinants in feedback loops by altering societal understanding, policy, and practice.

Critical components of social systems are the ways in which they divide and categorize humanity into demographic categories such as “sexes,” “genders,” “races,” “classes,” etc., among which individuals and groups in power allocate and withhold societal resources, including rights and powers. These processes of allocation frame a society’s inequity and equity, and are commonly grounds of contention and struggle. Neither the categories of persons, nor allocations to them are immutable; they are invented and reinvented; they evolve over time. The history and transformations of categories of persons and allocations to them powerfully affect the health status of societal members so categorized.

Table 1.

Ten theoretical and conceptual issues.

| 1. What is a determinant? |

|---|

| 2. What makes a determinant a social determinant? |

| 3. Are health care and public health SDOH? |

| 4. Can SDOH be harmful and/or beneficial? |

| 5. What about an SDOH makes it a “structural” determinant? What distinguishes structural from non-structural determinants? |

| 6. What is the relationship of SDOH to other, non social (e.g., biological, psychological, environmental) causes? |

| 7. What is the causal flow of SDOH and other determinants of health? |

| 8. Is the cause of a SDOH also an SDOH, and, conversely, are all events caused by SDOH also SDOH? |

| 9. Are there basic, fundamental causes? |

| 10. Should we count as SDOH only those determinants that we can, at least in theory, modify? |

Racial categories are created through societal processes of racial ideology and practice, i.e., racism (or resistance to it), and it is these social processes rather than the racial categories themselves that are SDOH. Being labeled “Black” or “White” for example does not in itself determine health outcomes. It is the societal system of racism or anti-racism, i.e., the set of attitudes, practices, and institutions in which the labeling is embedded, that determines health outcomes for those labeled in the system. When Black racial identity is associated with racist ideologies, practices, and institutions, it has deleterious health consequences. When associated with anti-racist ideologies, practices, and institutions, Black racial identity can yield improved health consequences.

A critical example of SDOH with global consequences is the effects of human activity on the earth’s atmosphere and climate, e.g., global warming, that have accelerated over the past century. Human social activity associated with the accelerated carbonrelease has become a SDOH that will determine human survival on the planet.13,14

Simply because something is social does not imply that it is a determinant of health. Many social phenomena have been recognized as SDOH and others may be discovered and verified.15 However, we suspect that there are few social phenomena, i.e., components of societal systems, that have no health consequences. Furthermore, the influence of SDOH can vary across social settings and within settings, some SDOH are more important than others.16 One social phenomenon that may have minimal health consequences is symbol systems (alphabets, musical notations, numbers, gestures, etc.), which are part of the cultural aspects of a social system. They are signifiers, which do social work especially when assembled in a context, and are vehicles of representation and expression.

3. Are health care and public health practice SDOH? While the notion of SDOH clarifies the societal causes of health outcomes beyond medical and health care, nevertheless, medicine and health care are social institutions and thus are included among SDOH. Excluding them neglects important dynamics of the distribution and socially shaped delivery of health resources and services. As with other SDOH, harmful as well as beneficial facets of this SDOH are recognized in the distinction between practice and malpractice, governed by the system of professions.17

4. Can SDOH be harmful, or beneficial, or both? Many determinants can have either beneficial or harmful effects on health outcomes, or both. Take transportation: a transportation system dependent on automobiles, highways, and traffic allows the population to access societal resources, but can have harmful effects on longterm health, e.g., crashes and pollution, while a system of public transportation and one that encourages walking and biking can have relatively beneficial effects on long-term health. The determinant is a system of transportation, not one or another form of transportation alone. Rather than “food insecurity”,8 the generic concept is “food security” which can be present or absent in degrees. Rather than “precarious employment,”4 the generic concept is “employment.” Rather than “poverty,” the generic is “wealth,” of which poverty is one extreme. Rather than “racism,” the more comprehensive concept is “race ideologies and practices.” Many SDOH have positive and negative facets.

5. What about an SDOH makes it a “structural” determinant and distinct from non-structural determinants? Some SDOH are described as “structural,” e.g., “structural racism,” because they occur as patterned, prescriptive societal arrangements, both shaping and shaped by human activity; their existence in institutions and rules may persist independent of the participation of specific individuals. In addition to “infrastructure,” e.g., roads, community designs, and the buildings that house institutions—the “hard” structures—the “built environment” that has diverse health consequences, there are also “soft” structures, i.e., the forms of organization (government agencies, corporations, NGOs, democracies, dictatorships, etc.), the roles that they establish, the regulations and rules that they propose—that are also structures that guide human behavior and can have health consequences. The U.S. Senate persists independent of who its members are at any particular time. Structures are commonly accompanied and justified/rationalized with ideologies. The U.S. caste system described by Wilkerson18 is a structure.

What, then, are non-structural SDOH? Non-structural SDOH are behavioral choices individuals perform, in response to the options provided by the roles, rules, and values of institutional structures which they inhabit. Occupants of roles are often aware of the rules of behavior associated with their institutions and roles. They can follow these rules, manipulate them, or violate them. Observers of these behaviors can then accept or judge such behavior and allow it, or impose sanctions when the deviation from rules is deemed unacceptable (e.g., license revocation).

Perhaps the clearest and most important non-structural SDOH are preventive and risk behaviors. Preventive and risk behaviors are social in that they are socially conceived and framed and socially caused through socialization, social norms, and peer pressure. Solitary drinking is also social because it takes place within a broader societal environment with norms of drinking. Preventive and risk behaviors are also constrained and enabled by social determinants. If a community has limited transportation and has no fresh fruits or vegetables available or affordable—a common occurrence in poor neighborhoods—community members are unlikely to eat fresh fruits and vegetables. Preventive and risk behaviors are the responses to health resources and hazards available in diverse settings and allowing or constraining the behaviors known to have health consequences.

6. What is the relationship of SDOH to other, non-social (e.g., biological, psychological, environmental) determinants? That a certain phenomenon or process, e.g., education, is demonstrated to be a SDOH does not negate the relevance of mental, physiological, chemical, physical, etc. causes and processes determining health outcomes at the same time.2,19 Rather, part of the “mechanism” through which SDOH have their health consequences is by means of mental/psychological, physiological, chemical, etc. processes and pathways, i.e., “embodiment,” the way in which society gets into the body.1

In public health, the notion of “biological plausibility” is often cited as a criterion to determine causality; it is the mechanism hypothesized to link cause and outcome. The unstated assumption is that biology is the principal, if not the only science that might explain the link between a cause and an outcome in health-related events. In expanding the discipline of public health to include SDOH, it will be useful to add the notion of “social plausibility” and to include the wide range of social conditions and theory to explain connections between SDOH and health-related outcomes.

7. What is the causal flow of SDOH and other determinants of health? Braveman and colleagues20 usefully distinguish upstream (also “distal”) and downstream (also “proximal”) SDOH in terms of relative position in causal sequences. Similarly, the WHO model21 includes both more-upstream structural SDOH, e.g., governance and societal values, and more-downstream intermediary SDOH, working conditions and psychosocial factors.

Frieden22 developed a “Health Impact Pyramid” version of the relationship between SDOH, referred to as “socioeconomic factors,” and more downstream forms of public health and clinical intervention. The focus is the interrelations among upstream and downstream determinants. Socioeconomic factors form the broad base of the pyramid, presumably indicating the breadth of influence on health outcomes. While downstream interventions, e.g., clinical encounters, address the health issues of smaller numbers of people at a time and may be labor-intensive, upstream interventions often affect many people, i.e., whole populations.22 Eliminating artificial trans-fats from food production has been politically difficult because of industry resistance, but, once artificial trans-fats are removed from the food environment, consumers no longer have to decide whether to consume them.23

8. Is the cause of a SDOH also an SDOH? A determinant of a SDOH is also a SDOH. Civil rights laws promise equitable access to specified societal resources, so that, if enforced, populations are guaranteed access to those resources, including SDOH. Thus, laws can be included among SDOH—they are causes of other SDOH.10

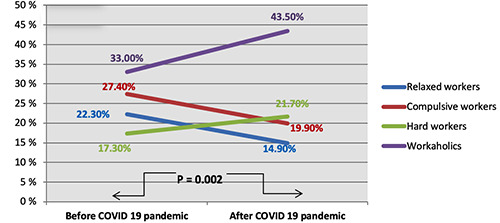

Are there basic, fundamental causes? Phelan and Link have usefully distinguished fundamental causes—the upstream, root SDOH that persistently have downstream SDOH consequences even though the downstream SDOH may change over time.24 For example, while the mechanisms of racism in the U.S. have evolved through history, racism has persisted as a fundamental cause underlying the changing mechanisms (Figure 1). The end of slavery was briefly followed by Reconstruction, but then by Jim Crow laws and Supreme Court decisions such as Plessy V. Fergusson; these are the SDOH mechanisms through which racism has been recreated and resisted over time. Reconstruction is an instance of a partially beneficent form of racial ideology and practice, also a component of the fundamental cause. Fundamental causes affect distribution of and access to “key resources”—knowledge, money, power, prestige, and social connections—which in turn affect opportunities for sickness and health by means of multiple more specific societal resources and hazards for health such as housing, education, and health care.24 Phelan and Link note that fundamental causes affect multiple disease outcomes by means of multiple risk factors.

10. Should we count as SDOH only those determinants that we can, at least in theory, modify? A great public health benefit of recognizing social determinants as critical components of public health knowledge and practice is that SDOH reveal a powerful array of intervention opportunities. However, the use of knowledge of SDOH for public health benefit requires a focus on SDOH that are mutable and “actionable.”25

What counts as mutable is largely a matter of the state of knowledge, capacity, and political will, all of which evolve over time. To begin, we are unlikely to know of all important SDOH and increasingly recognize SDOH in previously unrecognized arenas.15 Even when known, the institutionalization of universal health care and the mitigation of the harms of systemic racism depend greatly on political environment. Ultimately, all SDOH count, and as a society we are accountable for what is categorized as unmodifiable.

Figure 1.

How a fundamental cause of health in the U.S., i.e., racism, continues to produce downstream health effects.

A brief review of prominent claims concerning SDOH: Terminology surrounding SDOH varies markedly and key issues considered in this analysis are rarely explicitly addressed in the literature. 20,21,26-30 Causality is commonly ignored, or timidly addressed as “shaping.” What counts as social versus non-social is not generally considered.31 Presumably to emphasize non-medical causes, Braveman,20 Alderwick 26 and the WHO exclude medicine and health care from SDOH. Without explanation, Alderwick 26 excludes “commercial interest.” Krieger’s ecosocial approach is a broad conceptualization of this topic.1

A common definition of SDOH centers on phrases such as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age.” (e.g., WHO https://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/ finalreport/key_concepts/en/). On the face of it, this definition is too broad, including conditions that are clearly not social. Presumably not the seasons or volcanic eruptions which may be “conditions in which….” and also determinants of health, but are not social. The WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) has developed a more sophisticated conceptualization of SDOH with a focus on health equity.31 Our characterization of SDOH is consistent with the CSDH framework, and enhances that conceptualization by asserting explicit causal power of SDOH in the distribution of societal resources. Our analysis also aligns with the broader ecosocial framework.1

The conceptual validity of SDOH has been challenged by several public health scientists.32,33 Murray proposes that what should be studied are differences among individuals, and that the inclusion of social concepts, such as social status, in analyses is methodologically inappropriate because such categories are ill-defined and difficult, if not impossible to invalidate. In response, Braveman and colleagues35 note that social categories, such as race and social position, are methodologically the same as other analytic concepts, and can be validated empirically as are other factors in analyses.

Similarly, Rothman32 noted, “…social class, … is presumably causally related to few if any diseases but is a correlate of many diseases.” Rothman and colleagues later noted that “…the label denoted by a social class category is itself confounded by factors such as poverty or nutrition, these or other components of social class will ultimately serve as better explanations, causal explanations.” 34 However, denying that SDOH is a cause because it has confounding component causes is like claiming that cigarette smoke is not a true cause of lung cancer because it is not the smoke overall that is the cause, but specific chemical components of the smoke; while the specific chemical components are proximal causes of lung cancer, this does not invalidate cigarette smoke as also a cause.

Discussion

Social determinants of health are societal systems, their components, and the social resources and hazards for health that societal systems control and distribute, allocate and withhold, and that, in turn, cause health consequences, including changes in the trends and distributions of health. The SDOH perspective adds theoretical and practical power beyond traditional “host-agent-environment” foundations of public health. In contrast to persistent notions of “the natural course of disease,” the SDOH perspective recognizes societal forces that affect health conditions, illuminates global variability in societal effects, and allows the inclusion of new approaches to public health problems. The power of focusing upstream is multiplied because upstream causes are likely to have a greater cascading array of down stream consequences than more downstream causes.22 Attention to SDOH merits the same centrality and routinization in public health as other core concepts like immunization.

There are obstacles to the entry of public health practice into allied arenas addressing SDOH.

Many arenas found to be SDOH, e.g., wealth/poverty, wages and taxes, transportation, housing, education, have not been regarded as within the purview and authority of public health. While silos are useful for focusing attention, research effort, and program development, the recognition of common interests across silos (e.g., the well-being of publics) facilitates critical collaboration and avoids duplication of effort—or worse, working at crosspurposes. The sharing of expertise and program design and implementation among silos becomes possible and, most likely, more efficient and effective.

Standard public health training and expertise have not included much attention to SDOH; advances will require new learning, the development of cross-silo methods and research, the review of existing interventions, and development and implementation of new ones.15

The further upstream one looks to change policies, e.g., poverty, taxes, nutritional standards, the greater the political resistance and the greater the political will, effort, and force needed to change policy or program.22 Evidence for the relatively low cost of SDOH interventions,36 and the high cost of persisting harmful SDOH, 20 should build support for this expanded focus.

Acknowledgment

I am particularly grateful for the major contributions to this analysis of Dr. Mary Leinhos. Other colleagues have also contributed to my thinking: Professor Karen Emmons, Dr. Sevgi Aral, Andrew Hahn, and Professor Holbrook Robinson.

References

- 1.Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:668-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raphael D. Social determinants of health: present status, unanswered questions, and future directions. Int J Health Serv 2006;36:651-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Virchow R, Leubuscher R. [Die medicinische Reform: eine Wochenschrift: 1. und 2. Jahrgang: 1848/49].[in German]. Olms; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benach J, Vives A, Amable M, et al. Precarious employment: understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health 2014;35:229-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blouin C, Chopra M, van der Hoeven R. Trade and social determinants of health. Lancet 2009;373:502-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castañeda H, Holmes SM, Madrigal DS, et al. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health 2015;36:375-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czyzewski K. Colonialism as a broader social determinant of health. Int Indig Policy J 2011;2:5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nolan M, Rikard-Bell G, Mohsin M, Williams M. Food insecurity in three socially disadvantaged localities in Sydney, Australia. Health Promot J Austr 2006;17:247-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips SP. Defining and measuring gender: a social determinant of health whose time has come. Int J Equity Health 2005;4:1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn RA, Truman BI, Williams DR. Civil rights as determinants of public health and racial and ethnic health equity: health care, education, employment, and housing in the United States. SSM Popul Health 2018;4:17-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein B. What are social groups? Their metaphysics and how to classify them. Synthese 2019:1-34. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn RA, Schoch-Spana M. Anthropological foundations of public health; the case of COVID 19. Prev Med Rep 2021;22:101331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace-Wells D. The uninhabitable earth: Life after warming: Tim Duggan Books; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolbert E. Why call recent disasters ‘natural’ when they really aren't? National Geographic [Internet]. Available from: nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/why-call-recent-disastersnatural-when-they-really-are-not [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hahn RA. Two paths to health in all policies: The traditional public health path and the path of social determinants. Am J Public Health 2019;109:253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muennig P, Fiscella K, Tancredi D, Franks P. The relative health burden of selected social and behavioral risk factors in the United States: implications for policy. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1758-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abbott A.. The system of professions: An essay on the division of expert labor. University of Chicago Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkerson I. Caste (Oprah's Book Club): The origins of our discontents. New York: Random House; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Susser M, Susser E. Choosing a future for epidemiology: II. From black box to Chinese boxes and eco-epidemiology. Am J Public Health 1996;86:674-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health 2011;32:381-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health - Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health 2010;100:590-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Food and Drug Administration, HHS. Final determination regarding partially hydrogenated oils. Notification; declaratory order; extension of compliance date. Fed Regist 2018;83:23358-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phelan JC, Link BG. Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annu Rev Sociol 2015;41:311-30. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep 2014;129:S19-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Meanings and misunderstandings: a social determinants of health lexicon for health care systems. Milbank Q 2019;97:407-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krieger N. A glossary for social epidemiology. J Epidemiol Commun Health 2001;55:693-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Link BG, Phelan JC. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav 1995;Spec No:80-94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S. Depart Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Epstein B. Social ontology. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44489 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothman KJ. Modern epidemiology. Boston: Little Brown; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray CJ, Gakidou EE, Frenk J. Health inequalities and social group differences: what should we measure?. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1999;77(7):537. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothman KJ, Stein Z, Susser M. Rebuilding bridges: what is the real role of social class in disease occurrence? Eur J Epidemiol 2011;26:431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braveman P, Krieger N, Lynch J. Health inequalities and social inequalities in health. Bull World Health Organ 2000;78:232-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz MH. Structural interventions for addressing chronic health problems. JAMA 2009;302:683-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]