Abstract

People tend to alleviate their negative emotions by shopping. Considering the change of shopping behavior during COVID-19 outbreak, negative emotions are the key contributors to this change. In this light, this study aims to investigate how negative emotions caused by COVID-19 affect shopping behaviors. This study classified consumer groups based on their perceived negative emotions (i.e., anxiety, fear, depression, anger, and boredom). By clustering analysis, four groups (i.e., group of anxiety, depression, anger, and indifference) were derived. Then, this study examined how each of the emotional groups differently affect the shopping-related motivations (i.e., mood alleviation, shopping enjoyment, socialization seeking, and self-control seeking) and shopping behaviors (i.e., shopping for high-priced goods and buying of bulk goods). Results revealed all emotional groups affect socialization seeking and influence high-priced shopping intentions. However, depression and indifference are positively associated with socialization seeking and influence bulk shopping intentions. In addition, other emotions except for anxiety affect mood alleviation and influence high-priced shopping intentions. Finally, anger is associated with self-control seeking and affects bulk shopping intentions. This study enables practitioners and researchers to better understand how people control negative emotions by shopping in pandemic situations such as the current COVID-19 crisis.

Keywords: Revenge spending, Shopping behavior, COVID-19, Emotions during a pandemic

1. Introduction

The rapid spread of COVID-19 since late 2019 has caused many people to refrain from outdoor and collective activities to prevent infections. During this pandemic, people have reported experiencing negative emotional states such as depression (Chao et al., 2020; Mazza et al., 2020), boredom (Chao et al., 2020), anxiety (Maza et al., 2020), anger (Trnka and Lorencova, 2020), and fear because of the uncertainty about when the pandemic will end (Addo et al., 2020). The affective heuristics and cognitive appraisal theory of emotion posits that people use emotions to adjudge dangerous situations (Lazarus, 1991, 2001). Thus, the factor of emotions precedes the determination of actions to evaluate circumstances and respond to risks (Lazarus, 1991; Slovic et al., 2004). In particular, people predominantly experience negative emotions such as fear, anger, anxiety, and sadness when confronted with danger. These moods affect how people react and behave in the face of a threat (Slovic et al., 2004).

Indeed, people display significantly changing behaviors because of the adverse emotions elicited by COVID-19, especially with respect to consumption. For example, panic buying is exemplified by consumers who stock inordinate quantities of daily essentials such as toilet papers and canned food because of the fear triggered by the uncertainty about when the pandemic will end (Islam et al., 2021; Naeem, 2021; Omar et al., 2021; Prentice et al., 2020). Others may demonstrate the behavior designated as revenge spending and aggressively buy discrete items to relieve suppressed and negative emotions, including luxury goods. Items subject to revenge spending can ease negative emotions through consumption regardless of their necessity or immediate use. Duty-free sales in 2020 in Hainan more than doubled the 2019 aggregates since the COVID-19 outbreak and soared 148.7% year-on-year to 1.04 billion yuan during China's National Day, the longest holiday in China (Huaxia, 2020). A similar phenomenon occurred in South Korea and the United States (Lee, 2021; Phillips, 2021). Those who could not spend money on travel, dining out, or shopping at the same scales as before the COVID-19 outbreak took to aggressive spending with a vengeance when the opportunities emerged (Lee, 2021; Phillips, 2021).

According to Hama (2001), the surge in spending is primarily related to the desire of people to relieve unexpected stress through shopping after the pandemic. Moreover, many retail therapy studies have evidenced that people reduce negative emotions such as depression, anxiety, and sadness by shopping (Atalay and Meloy, 2011; Kang and Johnson, 2010; Rick et al., 2014). In other words, people shop to make themselves feel better. Additionally, the terror management theory (TMT) postulates that people are motivated to overcome their fears by compensating for the sensed threat to their survival (Greenberg et al., 1997; Yuen et al., 2020). According to retail therapy and TMT, people experience negative emotions during unforeseen and uncontrolled circumstances such as the current COVID-19 pandemic, which causes them to shop to mitigate these adverse feelings.

However, the extant studies on consumption behavior during disasters have primarily attended to panic buying (Islam et al., 2021; Naeem, 2021; Omar et al., 2021; Prentice et al., 2020; Yuen et al., 2020), while revenge spending has been addressed mainly by the media. Little is known in academic research on revenge spending (Lins et al., 2021; Malhotra, 2021) about why people overspend or how revenge expenditures vary according to individual personalities. Kennett-Hensel et al. (2012) have reported that life events such as hurricanes cause people emotional distress such as stress, anxiety, and depression. Hurricane survivors express diverse shopping behaviors: some purchase survival necessities while others buy for pleasure. The latter group may spend excessive amounts on music, clothes, designer products, and other luxury goods or avail of services such as pedicures, facials, massages, or travel to relieve the pain and negative feelings evoked by the disaster. The findings of Kennett‐Hensel et al. (2012) study evinced that people tend to stock up on necessities in a disaster situation or aggressively purchase relatively unnecessary and expensive goods and services. However, their findings did not indicate how shopping behaviors could be associated with panic buying and revenge spending according to individual characteristics (or emotions).

The COVID-19 situation is unprecedented because it has lasted longer than other disasters; people must maintain social distance in public, which has caused considerable social isolation. Consequently, the current pandemic has taken a devastating toll on the mental health of people, stimulating stress and numerous negative emotions such as fear, anxiety, boredom, depression, and anger (Brooks et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Mahmud et al., 2020). Individuals process emotions such as fear, sadness, anxiety, and anger in different ways and thus exhibit distinct behaviors (Lazarus, 1991). For example, existing studies have reported that people are likely to adopt a deliberate process when they feel sadness, whereas anger results in the adoption of a less deliberate process based on a peripheral cue (Bodenhausen et al., 1994). Further, fear, sadness, and worry have been found to affect preventive behaviors, but anger affects punishment and avoidance behaviors (Lazarus, 1991). In sum, the moods of people influence certain behaviors when they face negative situations. People tend to alleviate their negative emotions through shopping (Atalay and Meloy, 2011; Kang and Johnson, 2010; Rick et al., 2014), and reactions to adverse emotions vary according to individual characteristics.2 Hence, researchers must examine how distinct emotions influence shopping motives and shopping attitudes.

The current study proposed the following research question in the context of the above discussion:

How can people be categorized into groups according to the negative emotions they sense due to COVID-19?

The present study addressed this research question by using previously conducted studies to first explore and confirm the psychological states of people caught in situations of disaster. It then selected negative emotions (i.e., anxiety, fear, boredom, depression, and anger) that could occur during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the degree to which individuals sense negative emotions varies; therefore, this study divided people into groups by conducting a K-means clustering based on participant responses to every emotion survey questionnaire. Given the realities of shopping, some people spend on more expensive products to relieve stress, and others buy lots of inexpensive items in large quantities (Lee, 2021; Phillips, 2021). The same applies to disaster situations: some people purchase survival necessities while others buy music, artwork pieces, designer products, and such luxuries to reduce stress and alleviate negative feelings evoked by the disaster (Kennett-Hensel et al., 2012; Yuen et al., 2020). The present study referred to panic buying as bulk goods shopping and revenge spending as the increased purchase of high-priced goods than usual.

The second research question was postulated in consideration of the scope of revenge spending and panic buying:

How do the shopping motives affecting (a) shopping for high-priced goods and (b) buying of bulk goods differ according to the categories established for the first research question?

The traditional shopping-related research on consumer spending attitudes in disaster situations focuses on panic buying, which denotes the bulk purchase of daily necessities. In contrast, this study expanded the range of items and investigated whether people were more inclined to hoard cheap items of daily need during the COVID-19 pandemic or to purchase more expensive products than usual. Additionally, shopping motives (e.g., mood alleviation, socialization seeking, self-control seeking, and enjoyment) that could appear in the COVID-19 situation were selected to determine how shopping motives differently influenced shopping attitudes according to the identified emotions.

2. Literature review and hypotheses

2.1. Retail therapy and terror management theory

During natural disasters, such as hurricanes or earthquakes, and epidemics, people experience negative emotions, such as fear and anxiety, and sense of threat to their survival. People are experiencing similar negative feelings of frustration because of uncertainty and fear of infection during the current COVID-19 pandemic. The most common emotions that could occur include anxiety, fear, boredom, depression, and anger (Brooks et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2020; Joensen et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Mahmud et al., 2020). Retail therapy studies have demonstrated that in negative situations, people try to change their mood or relax their mind and body by shopping (Atalay and Meloy, 2011; Kang and Johnson, 2010). Besides coping with everyday stress, shopping also serves as a breakthrough solution to relieve the stress caused by the threat to survival. The TMT theory posits that the motivation for rewarding behavior to overcome such fear and anxiety increases when an individual senses a threat to survival (Barnes, 2021; Greenberg et al., 1997; Pyszczynski et al., 2021; Yuen et al., 2020). In other words, stress and loss of control in a disaster situation lead to impulsive purchase intentions (Sneath et al., 2009). Hence, based on retail therapy and TMT, people who experience negative emotions in disaster situations, such as COVID-19, are assumed to shop to alleviate their negative emotions, such as fear and anxiety.

2.2. Negative emotions during disaster situations

Individual feelings vary according to specific situations; thus, people perceive and experience varied emotions about the COVID-19 circumstances. A study on people's psychological states toward COVID-19 has found that people feel diverse negative emotions such as depression, anxiety, fear, stress, boredom, loneliness, and anger (Brooks et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2020; Joensen et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Mahmud et al., 2020). Accordingly, as emotions are unique and distinct depending on individuals, shopping motives and attitudes would differ for each felt emotion.

In generally, a feeling of anxiety indicates one's feeling when they are nervous or worried about something might happen in the future (Endler and Kocovski, 2001). In this sense, Schmidt et al. (2021) reported that when people are worried and anxious during the COVID-19 pandemic, they are more likely to stockpile because of the threat to survive. Differences between fear and anxiety are subtle, so they are generally considered as the similar feeling (Sylvers et al., 2011). Anxiety is an uncomfortable feeling towards uncertainty, whereas people feel fear about a certain target or a situation (Sylyers et al., 2011). Thus, the feeling of fear of COVID-19 is a psychological factor that cause people to shop more online and the fear increased consumers' stockpiling behavior (Naeem, 2021). Depression is when people feel sad and useless about themselves (Townend et al., 2010). Previous research indicated that depressed people are insecure about themselves and tend to have low self-control (Özdemir et al., 2014), which is positively associated with the consumption of luxury brand goods (Vansteenkiste et al., 2006). and compulsive buying behavior (Mueller et al., 2011). Lastly, the depressed are relatively vulnerable for addiction, especially for the shopping addiction (Özdemir et al., 2014). Anger is a negative emotional state that one feels when someone feels something is unfair and out of control (Nasir and Abd Ghani, 2014). When people feel angry, they are likely to lose their temper. In the end, anger can cause compulsive buying behavior (Pandya and Pandya, 2020). Boredom is a feeling of unsatisfied by certain activities or people, so it leads a lack of concentration on desired tasks (Deng et al., 2020). To avoid feeling bored, people tend to seek for entertaining tasks for themselves and go shopping (Sundström et al., 2019). During COVID-19, people are forced to stay home and keep distancing from other people, so they feel bored out of a lack of novel stimuli. Deng et al. (2020) reported that people are willing to shop to avoid boredom and increase higher stimuli during COVID-19. In this sense, each of the negative emotions indicates distinct characteristics and different shopping attitudes. In a long-lasting COVID-19 outbreak situation, negative emotions vary with the individual and those various emotions can be categorized in a certain way. Thus, it is necessary to investigate the differences between shopping motivations and attitudes depending on the categorized feelings that are negatively caused by COVID-19.

However, the related extant research on shopping attitudes in disaster situations has mainly focused on how fear caused by natural disasters such as hurricanes, earthquakes, and heavy rains affects individual shopping behavior (Kennett-Hensel et al., 2012; Larson and Shin, 2018; Sneath et al., 2009). For temporary changes in shopping attitudes because of infectious diseases such as SARS and MERS, several studies have been conducted on panic buying of living necessities for survival and a greater engagement in online shopping due to fear of infection (Forbes, 2017; Mahmud et al., 2020; Yuen et al., 2020). Little is known about what emotions people feel due to COVID-19 and how these emotions influence their shopping attitudes.

2.3. Classification of shoppers

As mentioned in section 2.1, 2.2, people shop to alleviate their negative emotions (Brooks et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2020; Joensen et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Mahmud et al., 2020), and each negative emotion has distinct psychological traits and indicates different shopping behaviors (Deng et al., 2020; Mueller et al., 2011; Naeem, 2021; Özdemir et al., 2014; Pandya and Pandya, 2020; Schmidt et al., 2021; Vansteenkiste et al., 2006). Because COVID-19 has lasted over a longer time than other disasters, people feel not only fear of infection but also other negative feelings such as anxiety and fear of losing their jobs. In addition, they feel bored and depressed from social distancing. In this light, people might feel complicated negative feelings toward COVID-19. Thus, those complex negative feelings differently affect shopping motivations and behaviors.

Previous studies on shopping classified shopping behaviors based on individuals’ emotions and shopping preferences (Challet-Bouju et al., 2020, DeSarbo and Edwards, 1996, Hampson and McGoldrick, 2013, Reynolds et al., 2002, Rohm and Swaminathan, 2004, Stone, 1954). Studies that classified groups according to emotional states investigated what kind of emotions people exhibited compulsive buying behavior (Challet-Bouju et al., 2020, DeSarbo and Edwards, 1996): whether people have a positive or negative response on compulsive buying. When it comes to personal preferences, people are categorized into utilitarian, heuristic, and apathetic shoppers (Hampson and McGoldrick, 2013, Reynolds et al., 2002, Rohm and Swaminathan, 2004, Stone, 1954). There were people who shop based on their economic situation: utilitarian or economic, whereas people who thought that shopping was enjoyable: hedonic or enthusiast, or people who thought the act of shopping itself was not given much meaning: apathetic or indeterminate.

Shopping behavior research under a natural disaster has mainly explored panic buying behavior (Islam et al., 2021; Naeem, 2021; Omar et al., 2021; Prentice et al., 2020; Yuen et al., 2020). However, under COVID-19, not only panic buying but also luxury brand goods consumption is observed. To date, very little is known about the relation between psychological factors and resulting shopping performance. Thus, the purpose of this study was to better understand potential differences in shopping motivations and shopping attitudes in relation to negative feelings an individual might feel during COVID-19.

2.4. Shopping behavior during disaster situations: panic buying and revenge spending

For shopping attitudes in disaster situations, many studies have examined the behavior of panic buying, which refers to the bulk purchase of daily necessities for survival (Islam et al., 2021; Naeem, 2021; Omar et al., 2021; Prentice et al., 2020; Yuen et al., 2020). Toilet paper and canned food are examples of such daily necessities in disaster situations (or immediately after a disaster if the price of a certain item rises or the item disappears from shelves) (Yuen et al., 2020). The panic buying phenomenon has recently attracted attention during the COVID-19 outbreak; however, panic buying is not a new phenomenon. It has previously been noted during natural disasters such as earthquakes and hurricanes (Forbes, 2017; Yuen et al., 2020). Yuen et al. (2020) conducted a systematic review of literature on panic buying and summarized the following causes for it: perceived threat, perceived scarcity, fear of the unknown, coping behavior, and social psychological factors. People tend to purchase more goods particularly because of fear and anxiety due to instability and uncertainty in disaster situation, which leads to a sense of security and lower stress (Kennett-Hensel et al., 2012; Sneath et al., 2009).

In reality, apart from purchasing necessities for survival in disaster circumstances, people purchase music, clothes, designer products, and other products to relieve the pain and negative feelings toward the disaster (Kennett-Hensel et al., 2012; Yuen et al., 2020). Some consumers aggressively spend a lot of money on designer brand goods even though such products serve no immediate use in COVID-19 situation. The consumption behavior has been observed in many countries (Huaxia, 2020; Lee, 2021; Malhotra, 2021; Phillips, 2021). Such shopping attitudes could release suppressed and negative emotions about COVID-19 (Malhotra, 2021). This buying behavior is referred to as “revenge spending”. Taken together, we have witnessed people's consumption behavior changes during the pandemic that some people stock up on daily essentials, which is panic buying, whereas others aggressively purchase expensive, designer products, which is revenge shopping.

Therefore, to analyze the shopping behavior in the COVID-19 situation more accurately, this study intends to add and examine the intention to purchase expensive goods, revenge shopping, which has not been explored much in previous studies along with panic buying behavior. In sum, to determine the shopping attitudes, this study focused on perceived changes in consumption. Specifically, this study investigated whether individuals purchased more expensive items after the COVID-19 than before and whether they purchased more bulk of goods.

2.5. The impact of shopping motivations on shopping intentions (purchasing high-priced or bulk goods)

Negative emotions in disaster situations affect buying behavior, and emotional factors are closely related to shopping motivation. Shopping motivation is one of the most important factors of consumer buying behavior (Tauber, 1995; Wagner and Rudolph, 2010). Previous literature has mentioned that there are two main streams for shopping motivations: hedonic and utilitarian values (Babin et al., 1994; Scarpi et al., 2014; Wagner and Rudolph, 2010). Hedonic shopping means that consumers purchase of goods and services for personal pleasure, whereas utilitarianism is related to efficiency and rationality—so people buy certain products because of their necessities (Babin et al., 1994; Scarpi et al., 2014; Wagner and Rudolph, 2010). However, it is demanding and challenging to explain how negative distress caused by an uncertain and insecure situation of COVID-19 are relieved by the existing hedonic and utilitarian shopping motives. Social distancing to prevent infections has led everyday life changes, which trigger several negative emotions: the fear and anxiety of viral infections (Addo et al., 2020), depression, boredom, or anger (Chao et al., 2020; Mazza et al., 2020; Trnka and Lorencova, 2020), from suppressed, controlled social activities. Shopping for alleviating those unfavorable feelings could differ from shopping for necessities or shopping for personal recreation. Thus, centering on the specific situation of COVID-19, the present study selected shopping motivations (e.g., mood alleviation, shopping enjoyment, socializing, and self-control seeking) that are easily influenced by negative feelings in a COVID-19.

One of the motivations covered in retail therapy is mood alleviation, which elucidates that people go shopping to make them feel better when they are in a bad mood (Kacen, 1998, Kacen and Friese, 1999, Kang and Johnson, 2010, Luomala, 2002). Luomala (2002) states that shopping effectively creates a sense of being active and improves negative moods such as irritation and stress. Such mood-alleviating shopping denotes self-gifting behavior (Luomala, 1998). People can feel intrinsic enjoyment and hedonic gratification even when they do not actually buy anything and only perform window shopping (Lee et al., 2018). Meanwhile, some studies have stated that the consumption of luxuries is effective in alleviating negative feelings and eliciting better moods (Gould, 1991; Lazarus, 1991; Luce, 1998; Tsai, 2005). As such, previous studies have demonstrated that the purchase of both expensive and inexpensive items can help with mood alleviation. However, not many studies have considered the price levels of the items targeted for consumption. Thus, this study predicted that the motive of mood alleviation affects the purchase of high-priced and bulk goods.

Additionally, the present study further assumed that shopping enjoyment, which is one of the fundamental motivations for shopping behavior, could also be a motivation for shopping regardless of the COVID-19 situation. Although shopping with an enjoyable mood may be difficult for people having negative emotions, such as depression, fear, and anger due to COVID-19, seeking enjoyment can be a motivation for shopping because shopping affects mood alleviation (Kang and Johnson, 2010; Luomala, 2002). Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H1

Mood alleviation positively affects the intention to purchase high-priced goods (H1a) and bulk goods (H1b).

H2

Shopping enjoyment positively affects the intention to purchase high-priced goods (H2a) and bulk goods (H2b).

Socialization is another aspect of the motivation for shopping intentions, which can stimulate the desire to buy. Socializing refers to shopping with close friends or family and bonding with them while shopping (Arnold and Reynolds, 2003; Aydın, 2019). Socialization occurs while individuals explore, engage with, and adapt to an organization, and interaction between individuals is also crucial for socialization (Fetherston, 2017). Socializing is predominantly achieved through offline interchanges with others; thus, socializing is significantly suppressed when social distancing is enforced worldwide, as in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. This made people seeking more socialization than usual. Indeed, when a particular need is suppressed, people have compensatory consumption at times to receive emotional compensation through shopping (Woodruffe, 1997). Compensatory consumption is reflected in several ways. It may be articulated through conspicuous consumption or spending a lot of money on luxury goods that are easily identifiable by others (Abdalla and Zambaldi, 2016; Kastanakis and Balabanis, 2014; Rucker and Galinsky, 2008). Conspicuous consumption also compensates for the lack of social group activities and the absence of a sense of belonging.

In addition, compensatory consumption is closely related to emotions in terms of compensating for the lack of emotional reactions (Koles et al., 2018). In this regard, when the risk for survival is high because of COVID-19, buying a large number of survival-related items could be a compensatory consumption for safety from external stress. Therefore, the current study predicts that mass purchases of items of daily necessity such as tissues and masks could be a type of compensatory consumption and that the motivation for suppressed socialization triggers compensatory shopping. Therefore, the following hypothesis is postulated:

H3

Socialization seeking positively influences the intention to purchase high-priced goods (H3a) and purchase bulk goods (H3b).

Next, self-control seeking, which means the capacity of individuals to control their emotions through shopping and to seek such control, is another motivation to stimulate shopping intentions. Previous studies on retail therapy have shown a positive effects of self-control seeking on purchasing by choice, reducing anxiety and depression, and improving personal control (Atalay and Meloy, 2011; Rick et al., 2014; Russell and Rogers, 2019). Even the act of selecting items without buying anything has been proven to change a person's mood. It is thus predicted that shopping could satisfy an individual's motivation to seek self-control. People are likely to experience a sense of loss when they cannot do things they could enjoy in their daily lives. Thus, we predict that shopping can represent a means of proving self-control-seeking by an individual. Moreover, self-control seeking is itself assumed to act as a motivation for shopping, regardless of whether high-priced luxury products or bulk goods are intended to be purchased. It is hence hypothesized:

H4

Self-control seeking positively affects the intention to purchase high-priced goods (H4a) and purchase bulk goods (H4b).

2.6. Motivation, intention, and actual purchase

The theory of reasoned action (TRA) is widely used for understanding an individual's voluntary behavior by examining the basic motivations for performing an action (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975; Ajzen, 1991). TRA posits that intention has long been identified as a cause of reasoned behavior. According to Ajzen and Fishbein (1980), both internal factors (e.g., individual perceptions of events) and external factors (e.g., social influences) affects individuals to conduct of certain actions, and as behavior is determined by the human intent to perform, hence, individual intentions can act as behavioral motivations. Moreover, the more favorable and positive the intention, the stronger the actual behavior be to perform (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). For example, many previous studies have found that motivation toward a behavior affects volitional behavior in a variety of domains such as social commerce (Yeon et al., 2019), online video advertising (Lee et al., 2013), and senior management (Wu, 2003). In this study, we expect that TRA will give useful explanations for understanding consumers' revenge shopping behavior and following hypotheses were derived:

H5

The intention to buy high-priced goods positively affects the purchase of high-priced goods.

H6

The intention to buy goods in bulk affects the purchase of bulk goods.

2.7. Research model

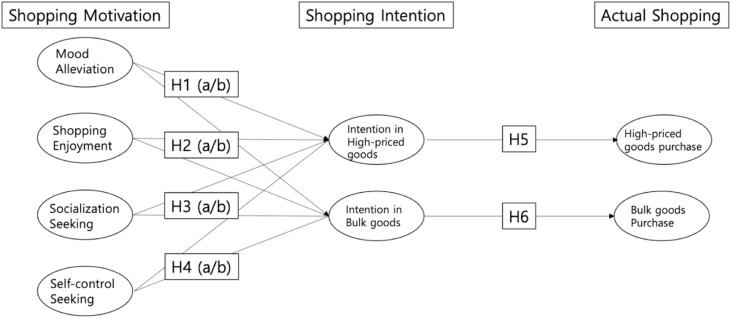

Fig. 1 presents the research model for this study, illustrating all the hypotheses stated in sections 2.1, 2.2, 2.3.

Fig. 1.

Proposed research model.

In this study, reflective indicators are used to measure latent variables. Unlike reflective indicators, formative indicators were considered to cause constructs (Blalock, 1971), and a construct is formed or induced by its measures (Fornell and Bookstein, 1982). According to Roberts and Thatcher (2009), formative indicators can be used when (1) the indicators define the characteristics of a construct, (2) changes in the indicators cause changes in the construct, and (3) eliminating an indicator alters the conceptual domain of the construct. In this study, however, the indicators share a common theme and have the same antecedents and consequences. Moreover, a change in one indicator is associated with a change in all other indicators; therefore, this study used reflective indicators rather than formative indicators.

3. Methodology

3.1. Clustering

This study recruited respondents from August 25 to August 28, 2020, through a Korean online survey company, stipulating online shopping experience. During the survey, the cumulative number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in South Korea was 1506 in July and 5642 in August; that is, secondary propagation existed in which over 4000 people were confirmed during August only (an approximate increase of 3.75 times) (KOSIS, 2021). That is why we assumed survey respondents naturally felt negative emotions in this period. However, in order to identify the emotional factors that induce revenge consumption in the COVID-19 situation, we clustered survey respondents based on consumers’ emotional state. Following prior studies, we divided negative emotions of consumers that may appear in disaster situations such as COVID-19 into five dimensions: anxiety, fear, boredom, depression, and anger. Moreover, we constructed a questionnaire based on these groups.

The COVID-19 pandemic differs from the traditional disaster situation in that it extremely restricts people's social life and that it lasts for a long time. According to studies on the psychological state in COVID-19, people experience various negative emotions, including anxiety about losing their job (Mahmud et al., 2020), fear of infection, stress (Brooks et al., 2020), boredom, loneliness, depression (Holmes et al., 2020), and even anger (Li et al., 2020; Joensen et al., 2020). These emotions are caused by seemingly never-ending social distancing. Appendix A shows the items used to measure the five emotions based on the hitherto studies (Ahorsu et al., 2020; Cella et al., 2007; Fahlman et al., 2013; Farmer and Sundberg, 1986; Harper et al., 2020; Spielberger et al., 1985).

Although the questionnaire was designed to capture five emotional dimensions based on the existing literature, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to make a more explicit mutual orthogonal set between the five emotions. This procedure has the advantage of increasing the efficiency of subsequent clustering because it reduces emotional dimensions consisting of factors that can best explain each dimension. The results of the PCA with 25 items in the questionnaire are presented in Table 1 . Of the total variance of the data, 76.4% can be accounted for when reduced to four dimensions (the accumulated sum of proportion of variance is 0.764 from factor 1 to 4). A slight increase (about 3%) of the total variance was observed, adding with one more factor. Thus, four dimensions were deemed sufficient for the most efficient explanation of the negative emotions experienced by individuals. Therefore, clustering analysis was performed based on these four factors.

Table 1.

Principle component analysis of the importance of components.

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Factor 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of variance | 0.507 | 0.129 | 0.075 | 0.054 | 0.029 | 0.021 |

| Cumulative proportion | 0.507 | 0.636 | 0.710 | 0.764 | 0.793 | 0.815 |

The factor loadings of items for the four factors are presented in Table 2 . This gives information on which emotion-measured items (A1: Anxiety, A2: Fear, A3: Boredom, A4: Depression, A5: Anger) contribute to which factors (Factors 1 to 4). Factor 1 is attributed mainly by Anxiety and Fear (however, the fifth questionnaire of Fear, A2-5, explains factor 2 better). Meanwhile, Factor 2 is attributed mainly by Depression, and a little bit of Fear and Anger. Factor 3 is mainly contributed by Boredom and with a bit of Depression and Anger. Lastly, Factor 4 is loaded by the items measured for Anger. Therefore, we can define four factors as follows: Factor 1 (Anxiety/Fear), Factor 2 (Depression), Factor 3 (Boredom), and Factor 4 (Anger). We proceeded the analysis with excluding the variable A3-5 to make the further analysis clear because it has the cross-loading issue with factor 2 and 3.

Table 2.

PCA factor loadings.

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1-1 | 0.781 | |||

| A1-2 | 0.882 | |||

| A1-3 | 0.853 | |||

| A1-4 | 0.892 | |||

| A1-5 | 0.844 | |||

| A2-1 | 0.800 | |||

| A2-2 | 0.726 | |||

| A2-3 | 0.733 | |||

| A2-4 | 0.773 | |||

| A2-5 | 0.362 | 0.601 | ||

| A4-1 | 0.723 | |||

| A4-2 | 0.721 | 0.341 | ||

| A4-3 | 0.641 | 0.388 | ||

| A4-4 | 0.740 | |||

| A4-5 | 0.809 | |||

| A5-5 | 0.675 | 0.463 | ||

| A3-1 | 0.848 | |||

| A3-2 | 0.828 | |||

| A3-3 | 0.707 | |||

| A3-4 | 0.616 | |||

| A3-5 | 0.491 | 0.534 | ||

| A5-1 | 0.371 | 0.371 | 0.652 | |

| A5-2 | 0.372 | 0.329 | 0.732 | |

| A5-3 | 0.403 | 0.761 | ||

| A5-4 | 0.503 | 0.711 |

We clustered survey respondents using the four abovementioned emotional factors. K-means clustering was used as a clustering algorithm. It is one of the unsupervised learning algorithms in the field of machine learning. It binds the closest observations based on the given variables; specifically, it combines observations into “k” number of clusters, and the number “k” must be determined by the researcher. The cluster division is done by minimizing the sum of squares of distances between the centroid of each group and observations within the group. The number of clusters, k, can be determined in many ways, but there are no superior or inferior methods in particular. All methods have their own strengths and weaknesses; thus, this study followed Charrad et al. (2014) method, using a package called NbCluster, which enables the calculation and comparison of 30 indicators to derive the optimal number of k in R statistic software. In the result of the “k” recommending algorithm, 15 indices out of 30 recommended the optimal k equals 4, 9 out of 30 recommended k equals3, and 3 recommended k equals5. Therefore, K-means clustering was performed with four clusters in this study.

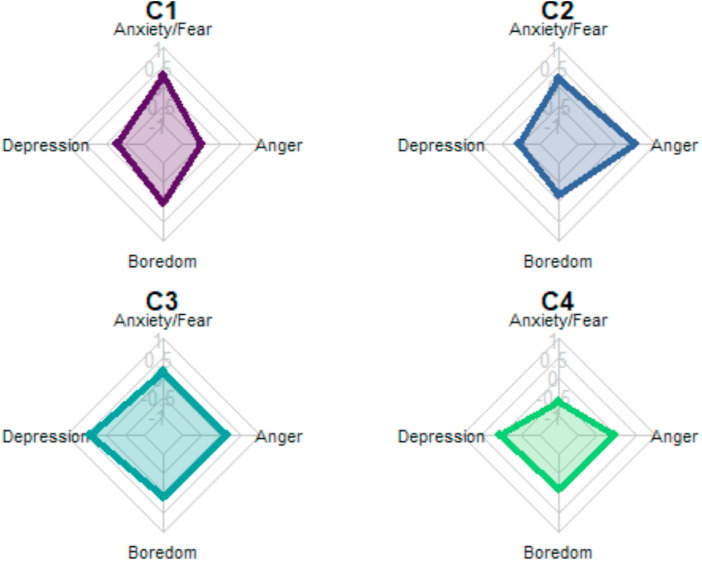

Fig. 2 illustrates the average value of emotions for each cluster in a radial graph when K = 4, which can show the characteristics of each cluster. The first cluster (C1) is the group who feels more anxiety and fear than other negative emotions in the COVID-19 crisis. C2 is the group of people who feel anger mostly, and C3 is biased toward depression when they are in this pandemic. Lastly, the C4 group consists of people who feel relatively low anxiety and fear, but average feelings of boredom, depression, and anger. We analyzed those people who consist of C4 usually have normal feelings even though they are in COVID-19 situation compared to the distributions of feelings in other clusters. That is, we named C4 as indifferent because their feelings were not controlled by COVID-19 situation. In sum, the four clusters were designated into groups named anxiety (C1), anger (C2), depression (C3), and indifference (C4).

Fig. 2.

Features of each cluster.

4. Results

4.1. Data collection

As mentioned in the Section 3.1, we conducted the survey from August 25 to August 28, 2020, with Korean respondents who have online shopping experience. With the data collected, we conducted confirmative factor analysis and structural equation analysis using SPSS statistics 25 and AMOS 18 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Reliability and validity tests were first conducted to verify the suitability of the questionnaire (e.g., the consistency of the variables) before the two abovementioned analyses were performed. The results of the reliability and validity tests are presented in Section 4.2. The confirmative factor and structural equation analyses are described in Section 4.3. After excluding data having low reliability and that were incorrectly entered, a total of 1174 respondents’ data were used to analyze empirical results. Appendix B presents the descriptive statistics of our sample. The descriptive statistics of each group are shown in Table 3 ; the percentages of those belonging to the 50–59 years age group are high in the anxiety group; 30–39 years, high in the anger group; 40–49 years, high in the depression group; and 50–59 years, high in the indifferent group.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of each group.

| Group | Age (years) | Male | Female | Subtotal | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 20–29 | 24 | 27 | 51 | 19.47% |

| 30–39 | 19 | 26 | 45 | 17.18% | |

| 40–49 | 22 | 25 | 47 | 17.94% | |

| 50–59 | 28 | 37 | 65 | 24.81% | |

| 60–69 | 24 | 30 | 54 | 20.61% | |

| Subtotal | 117 | 145 | 262 | 100% | |

| Anger | 20–29 | 11 | 28 | 39 | 19.80% |

| 30–39 | 27 | 28 | 55 | 27.92% | |

| 40–49 | 27 | 17 | 44 | 22.34% | |

| 50–59 | 15 | 16 | 31 | 15.74% | |

| 60–69 | 17 | 11 | 28 | 14.21% | |

| Subtotal | 97 | 100 | 197 | 100% | |

| Depression | 20–29 | 27 | 40 | 67 | 15.55% |

| 30–39 | 34 | 52 | 86 | 19.95% | |

| 40–49 | 52 | 56 | 108 | 25.06% | |

| 50–59 | 48 | 51 | 99 | 22.97% | |

| 60–69 | 31 | 40 | 71 | 16.47% | |

| Subtotal | 192 | 239 | 431 | 100% | |

| Indifferent | 20–29 | 34 | 14 | 48 | 16.90% |

| 30–39 | 33 | 9 | 42 | 14.79% | |

| 40–49 | 32 | 28 | 60 | 21.13% | |

| 50–59 | 47 | 33 | 80 | 28.17% | |

| 60–69 | 30 | 24 | 54 | 19.01% | |

| Subtotal | 176 | 108 | 284 | 100% |

4.2. Measurement reliability and validity tests

The survey items used in this study were slightly changed to suit the COVID-19 situation based on previous studies, and the detailed questionnaire is presented in the Appendix C. Before testing the reliability and validity of the data, common method variance (CMV) was performed because the data were collected via a self-reporting survey. As a results of a common latent factor (CLF) test, the differences in the standardized regression weights of all items between with and without CLF were found to be under 0.000 which means common method bias was not a concern in this study (Archimi et al., 2018). Table 4 shows the reliability results of variables and estimates. As described in Table 4, all the Cronbach's α and factor loading values exceeded the acceptable range of 0.7 (Cronbach, 1971); thus, the validity analysis was conducted. The results are shown in Table 5 . Moreover, average variance extracted (AVE) values and composite reliability (C.R.) values exceeded 0.7 respectively, then they met an acceptable range suggested by Bagozzi and Yi (1988). Additionally, square roots of AVE are higher than the correlation coefficient between latent variables, thus confirming the discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Estimates of variables.

| Latent variable | Observed variable | Cronbach's α |

Unstandardized estimate | Standardized estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood alleviation | Mood1 | 0.962 | 1 | 0.871 | |||

| Mood2 | 1.056 | 0.884 | 0.033 | 31.655 | *** | ||

| Mood3 | 1.161 | 0.96 | 0.049 | 23.623 | *** | ||

| Mood4 | 1.024 | 0.887 | 0.050 | 20.296 | *** | ||

| Mood5 | 0.895 | 0.803 | 0.053 | 16.752 | *** | ||

| Shopping enjoyment | Enjoy1 | 0.842 | 1 | 0.672 | |||

| Enjoy2 | 1.336 | 0.838 | 0.113 | 11.842 | *** | ||

| Enjoy3 | 1.628 | 0.926 | 0.131 | 12.385 | *** | ||

| Socialization seeking | Social1 | 0.871 | 1 | 0.703 | |||

| Social2 | 1.303 | 0.816 | 0.118 | 11.032 | *** | ||

| Social3 | 1.258 | 0.728 | 0.123 | 10.217 | *** | ||

| Social4 | 0.973 | 0.612 | 0.111 | 8.764 | *** | ||

| Self-control seeking | Control1 | 0.914 | 1 | 0.645 | |||

| Control2 | 1.376 | 0.839 | 0.108 | 12.745 | *** | ||

| Control3 | 1.547 | 0.946 | 0.125 | 12.379 | *** | ||

| Control4 | 1.282 | 0.844 | 0.111 | 11.54 | *** | ||

| Control5 | 0.979 | 0.670 | 0.102 | 9.567 | *** | ||

| Intention in high-priced goods shopping | High intention 1 | 0.933 | 1 | 0.737 | |||

| High intention 2 | 1.113 | 0.811 | 0.060 | 18.465 | *** | ||

| High intention 3 | 1.218 | 0.868 | 0.090 | 13.54 | *** | ||

| High intention 4 | 1.207 | 0.856 | 0.090 | 13.395 | *** | ||

| Intention in bulk goods shopping | Bulk intention 1 | 0.903 | 1 | 0.808 | |||

| Bulk intention 2 | 1.096 | 0.821 | 0.074 | 14.756 | *** | ||

| Bulk intention 3 | 0.964 | 0.783 | 0.069 | 13.958 | *** | ||

| Bulk intention 4 | 1.180 | 0.838 | 0.075 | 15.707 | *** | ||

| High-priced goods purchase | High purchase 1 | 0.915 | 1 | 0.905 | |||

| High purchase 2 | 1.025 | 0.932 | 0.046 | 22.316 | *** | ||

| High purchase 3 | 0.819 | 0.726 | 0.057 | 14.479 | *** | ||

| High purchase 4 | 0.688 | 0.686 | 0.052 | 13.237 | *** | ||

| Bulk goods purchase | Bulk purchase 1 | 0.891 | 1 | 0.847 | |||

| Bulk purchase 2 | 0.888 | 0.789 | 0.058 | 15.202 | *** | ||

| Bulk purchase 3 | 1.029 | 0.913 | 0.054 | 18.954 | *** | ||

| Bulk purchase 4 | 0.833 | 0.649 | 0.071 | 11.705 | *** |

Note: ***(p < 0.001), S.E. means standard errors, C.R. means critical ratios.

Table 5.

Results of convergent and discriminant validity.

| Latent variables | Mood alleviation | Shopping enjoyment | Socialization seeking | Self-control seeking | Intention in high-priced goods shopping | Intention in bulk goods shopping | High-priced goods purchase | Bulk goods purchase | AVE | C.R. | Mean | Std.dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood alleviation | 0.939 | 0.883 | 0.946 | 3.384 | 1.464 | |||||||

| Shopping enjoyment | 0.556 | 0.905 | 0.819 | 0.857 | 4.268 | 1.162 | ||||||

| Socialization seeking | 0.443 | 0.455 | 0.848 | 0.718 | 0.809 | 3.391 | 1.355 | |||||

| Self-control seeking | 0.679 | 0.715 | 0.602 | 0.893 | 0.797 | 0.895 | 3.802 | 1.401 | ||||

| Intention in high-priced goods shopping | 0.453 | 0.302 | 0.426 | 0.441 | 0.905 | 0.820 | 0.891 | 3.046 | 1.407 | |||

| Intention in bulk goods shopping | 0.492 | 0.363 | 0.371 | 0.477 | 0.659 | 0.902 | 0.813 | 0.886 | 3.274 | 1.310 | ||

| High-priced goods purchase | 0.390 | 0.341 | 0.355 | 0.387 | 0.636 | 0.600 | 0.905 | 0.819 | 0.889 | 3.120 | 1.470 | |

| Bulk goods purchase | 0.487 | 0.338 | 0.255 | 0.413 | 0.511 | 0.801 | 0.653 | 0.898 | 0.806 | 0.879 | 3.528 | 1.415 |

Notes: Diagonal elements (in bold) represent the square root of the AVE and Std.dev means standard deviation.

4.3. Results of hypothesis testing

We conducted structural equation analysis to verify hypotheses mentioned in Section 2. All four groups passed the acceptable range (CMIN/DF < 3, CFI >0.9, TLI >0.9, RMSEA <0.08) of the indicators of model fit (Bentler, 1990; Bentler and Bonett, 1980; Browne and Cudeck, 1992; Marsh and Hocevar, 1985). To be specific, CMIN/DF = 2.122, CFI = 0.927, TLI = 0.917, and RMSEA = 0.066 are the model fit of the anxiety group; CMIN/DF = 2.066, CFI = 0.915, TLI = 0.903, and RMSEA = 0.074 for the anger group; CMIN/DF = 2.568, CFI = 0.947, TLI = 0.940, and RMSEA = 0.060 for the depression group; and CMIN/DF = 2.607, CFI = 0.917, TLI = 0.906, and RMSEA = 0.075 for the indifferent group. The detailed hypothesis verification for each group is presented in Table 6 . The results of each group's variables are also presented in Sections 4.3.1, 4.3.2, 4.3.3, 4.3.4.

Table 6.

Hypotheses results of each group.

| Hypotheses |

Anxiety group |

Anger group |

Depression group |

Indifferent group |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Estimate (Unstandardized Estimate) | C.R. (P-value) | Standardized Estimate (Unstandardized Estimate) | C.R. (P-value) | Standardized Estimate (Unstandardized Estimate) | C.R. (P-value) | Standardized Estimate (Unstandardized Estimate) | C.R. (P-value) | |||

| Mood alleviation | → | Intention in high-priced goods | 0.261 (0.203) | 3.034 (0.002) | 0.179 (0.157) | 1.579 (0.114) | 0.277 (0.278) | 3.623 (***) | 0.260 (0.252) | 2.987 (0.003) |

| Mood alleviation | → | Intention in bulk goods | 0.326 (0.251) | 3.902 (***) | 0.052 (0.047) | 0.412 (0.68) | 0.138 (0.132) | 1.731 (0.083) | 0.233 (0.213) | 2.851 (0.004) |

| Shopping enjoyment | → | Intention in high-priced goods | −0.046 (−0.064) | −0.496 (0.62) | 0.091 (0.121) | 0.735 (0.463) | −0.01 (−0.016) | −0.129 (0.897) | −0.087 (−0.148) | −1.041 (0.298) |

| Shopping enjoyment | → | Intention in bulk goods | −0.004 (−0.006) | −0.046 (0.963) | 0.023 (0.031) | 0.165 (0.869) | 0.106 (0.168) | 1.337 (0.181) | −0.093 (−0.149) | −1.181 (0.237) |

| Socialization seeking | → | Intention in high-priced goods | 0.265 (0.311) | 3.031 (0.002) | 0.25 (0.304) | 2.916 (0.004) | 0.374 (0.396) | 5.699 (***) | 0.444 (0.486) | 5.442 (***) |

| Socialization seeking | → | Intention in bulk goods | 0.102 (0.118) | 1.247 (0.213) | 0.079 (0.099) | 0.854 (0.393) | 0.36 (0.363) | 5.251 (***) | 0.482 (0.496) | 6.215 (***) |

| Self-control seeking | → | Intention in high-priced goods | 0.149 (0.166) | 1.260 (0.208) | 0.185 (0.216) | 1.213 (0.225) | 0.015 (0.022) | 0.154 (0.877) | 0.019 (0.028) | 0.178 (0.859) |

| Self-control seeking | → | Intention in bulk goods | 0.203 (0.222) | 1.760 (0.078) | 0.352 (0.424) | 2.052 (0.04) | 0.014 (0.019) | 0.131 (0.896) | 0.083 (0.11) | 0.800 (0.424) |

| Intention in high-priced goods | → | High-priced goods purchase | 0.682 (0.904) | 10.141 (***) | 0.501 (0.656) | 7.036 (***) | 0.742 (0.809) | 15.633 (***) | 0.638 (0.728) | 11.605 (***) |

| Intention in bulk goods | → | Bulk goods purchase | 0.793 (0.950) | 12.267 (***) | 0.744 (0.754) | 10.256 (***) | 0.776 (0.845) | 16.187 (***) | 0.756 (0.819) | 14.224 (***) |

Note: ***(p < 0.001).

4.3.1. The anxiety group

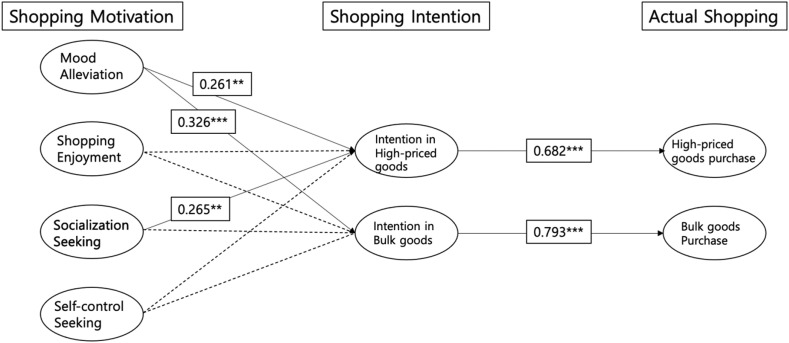

In the anxiety group, the mood alleviation motivation affected the shopping intentions of high-priced goods and bulk goods, and each shopping intention affected high-priced goods purchase and bulk goods purchase, respectively. However, mood alleviation influenced the bulk goods shopping intention (β = 0.326, p < 0.001) much more than the shopping intention toward high-priced goods (β = 0.261, p = 0.002). Thus, the bulk good shopping intention affected the actual buying behavior of bulk goods (β = 0.793, p = 0.002). Meanwhile, the shopping enjoyment motivation did not at all affect the intent to purchase high-priced goods (β = −0.046, p = 0.62) and bulk goods (β = −0.004, p = 0.963). Moreover, the socialization seeking motivation affects only high-priced goods shopping intention (β = 0.265, p = 0.002), not bulk goods shopping intention (β = 0.102, p = 0.213). Further, the self-control seeking motivation did not affect any shopping intentions (β = 0.149, p = 0.208; β = 0.203, p = 0.078). Finally, intention in high-priced goods shopping and bulk goods shopping affect high-priced goods purchase and bulk goods purchase, respectively (β = 0.682, p < 0.001; β = 0.793, p < 0.001). Therefore, H1 (a/b), H3(a), H5, and H6 were supported, but not H2(a/b), H3(b), and H4(a/b) (see Appendix D, Figure D1).

4.3.2. The anger group

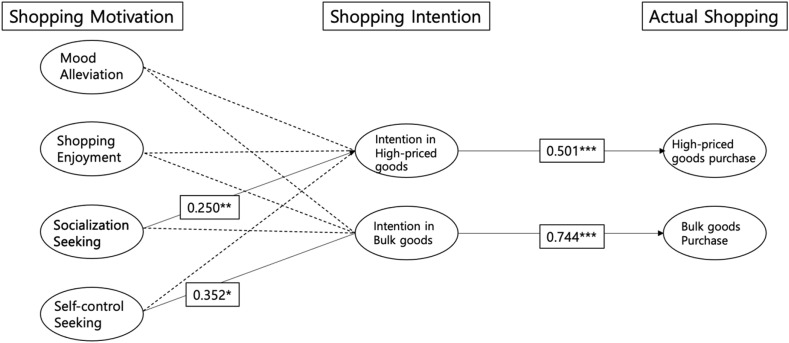

Respondents in the anger group had neither a causal relationship between mood alleviation and high-priced goods shopping intention (β = 0.179, p = 0.114), nor the causal relationship between mood alleviation and bulk goods shopping intention (β = 0.052, p = 0.680). Also, the shopping enjoyment motivation did not show either the intentions to buy high-priced goods (β = 0.091, p = 0.463), or bulk goods (β = 0.023, p = 0.869), which is the same result of the anxiety group. Moreover, the anger group responded that if they have socialization seeking motivation (β = 0.250, p = 0.004), they have intention to buy high-priced goods, but they have no intention to buy bulk goods (β = 0.079, p = 0.393). In case of the self-control seeking motivation, it did not affect high-priced goods shopping intention (β = 0.185, p = 0.225), but it affected bulk goods shopping intention (β = 0.352, p = 0.04), which yields different results compared with the anxiety group. Therefore, H3(a), H4(b), H5, and H6 were supported, but not H1(a/b), H2(a/b), H3(b), and H4(a) (see Appendix D, Figure D2).

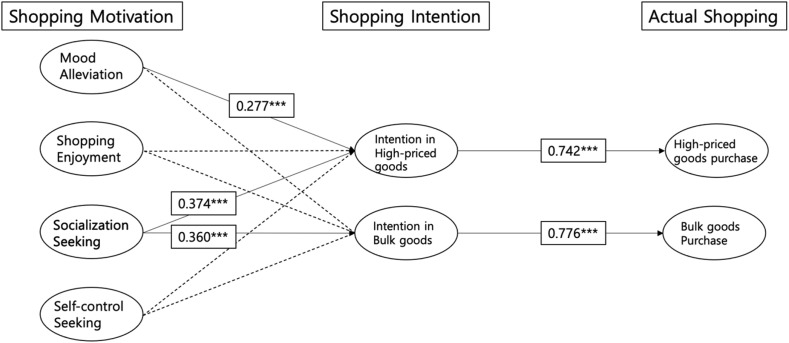

4.3.3. The depression group

Because the depression group literally had a depressed feeling after COVID-19, they had the intention to buy high-priced goods (β = 0.277, p < 0.001) but had no intention to buy bulk goods (β = 0.138, p = 0.083) if they had the mood alleviation motivation. The shopping enjoyment motivation affected neither high-priced goods intention (β = −0.010, p = 0.897) nor bulk goods intention (β = 0.106, p = 0.181), which is the same result in anxiety and anger groups. However, the socialization seeking motivation triggered the intention to buy high-priced goods (β = 0.374, p < 0.001) and bulk goods (β = 0.360, p < 0.001). Moreover, the self-control seeking motivation did not affect the intention to buy high-priced goods (β = 0.015, p = 0.877) and bulk goods (β = 0.014, p = 0.896). Therefore, H1(a), H3(a/b), H5, and H6 were supported, but not H1(b), H2(a/b), and H4(a/b) (see Appendix D, Figure D3).

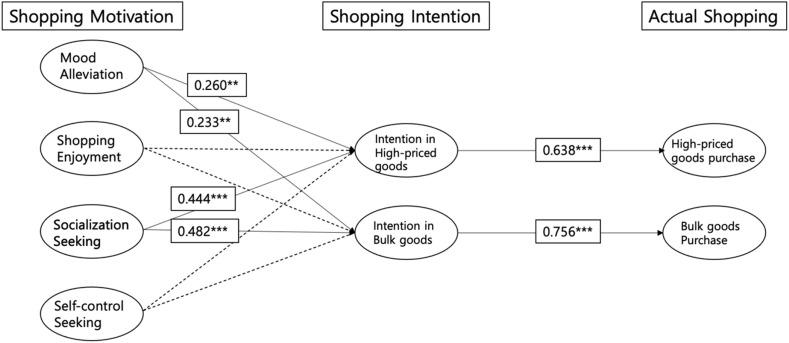

4.3.4. The indifferent group

The main features of indifferent group concerned the mood alleviation motivation and the socialization seeking motivation. Both motivations affected intentions to buy high-priced goods (β = 0.260, p = 0.003; β = 0.444, p < 0.001) and bulk goods (β = 0.233, p = 0.004; β = 0.482, p < 0.001). An interesting point here is that although the mood alleviation motivation influences higher intention to buy high-priced goods than bulk goods, the socialization seeking motivation influences higher intention to buy bulk goods than high-priced goods. Hence, the two intentions significantly affected high-priced goods purchase (β = 0.638, p < 0.001) and bulk goods purchase (β = 0.756, p < 0.001), respectively. The shopping enjoyment motivation and the self-control seeking motivation, however, did not significantly affect either high-priced goods intention (β = −0.087, p = 0.298; β = 0.019, p = 0.859) or bulk goods intention (β = −0.093, p = 0.237; β = 0.083, p = 0.424). Therefore, H1(a/b), H3(a/b), H5, and H6 were supported, but not H2(a/b) and H4(a/b) (see Appendix D, Figure D4).

5. Discussion

This study clustered the discrete negative emotions experienced by people during the COVID-19 pandemic and examined which shopping motivation (i.e., mood alleviation, shopping enjoyment, socialization seeking, and self-control seeking) exerted a major impact on the shopping intention (intention to shop for high-priced or bulk goods) of each group of respondents representing an adverse emotion.

The socialization seeking motivation impacted the intention of all the four groups to buy high-priced goods. Socialization seeking was found to relate closely to the desire of people want to meet others (Brown et al., 1993; Jones, 1999). However, the Korean government implemented social distancing protocols to curb the COVID-19 crisis, preventing social gatherings. Thus, it may be inferred that the sentiment of wanting to purchase expensive items (e.g., clothes and bags) occurred in all groups as a compensatory feeling. A high percentage of the indifference group was particularly represented by participants in their 50s with sufficient economic power and the urge to undertake social activities compared to the other age groups. These participants were willing to sustain their social activities through shopping during the COVID-19 situation. This result is consistent with the existing studies, which have shown that individuals view the process of communicating with store employees through shopping as a means of satisfying their socialization seeking motivation (Kim et al., 2005, Woodruffe‐Burton et al., 2002). On the other hand, the anxiety group also comprised a relatively high percentage of participants in their 50s; this outcome can be interpreted as the opposite situation to the indifference cohort. Respondents in their 50s could represent the contradictory condition of generally being parents worried about keeping their family members safe from COVID-19 and simultaneously needing to work in their places of employment. Thus, some people in their 50s could experience greater anxiety because of their worries about their family members or relatives, while others could feel indifferent because they prioritize how to survive the COVID-19 catastrophe. Hence, their nested situation makes people of this age either feel anxious or indifferent.

The degree to which socialization seeking affected the bulk purchase intention varied by group. The effects of socialization seeking on the bulk purchase intention were significant only in the depression and indifference groups, indicating that the motivation for socialization seeking is satisfied for those who are depressed through the purchase of goods on a large scale regardless of product price. Depressed people are reluctant to socialize with others (Steger and Kashdan, 2009). However, the results of the current study revealed that individuals depressed by COVID-19 still desired to socialize and buy large quantities of goods. Additionally, socialization can be pursued through bulk purchases by those indifferent to COVID-19, even the buying of products that are not necessarily expensive. Those who responded to this study's survey could have had indeterminate expectations of COVID-19 being dampened, which could motivate socializing.

Socialization seeking was followed by mood alleviation, which also significantly influenced the product purchase intentions of most groups. Mood alleviation aligns with an aspect of panic buying, the motivation to hoard daily necessities to lower anxiety in a disaster situation, and is thus an effective explanation of revenge spending (Forbes, 2017; Yuen et al., 2020). This mood alleviation has significantly affected the purchase intention of high-priced goods in the anxiety, depression, and indifferent groups, excluding the anger group. Members of the anger group were not influenced by the mood alleviation motivation to buy both high-priced and bulk purchases, indicating that these people did not want to shop to relieve their anger caused by COVID-19. This finding is inconsistent with the motivation of mood alleviation because anger depends on momentary emotions rather than a deliberate information process (Bodenhausen et al., 1994) and affects punishment and avoidance behavior (Lazarus, 1991). Additionally, mood alleviation significantly influenced purchase intentions toward both high-priced and bulk goods in the anxiety and indifference groups. The intent to purchase goods in bulk was more strongly influenced by mood alleviation in the anxiety group than the intent to buy high-priced goods. This outcome is congruent with Omar et al. (2021) analysis that anxiety-prone people are likely to stockpile purchased items. However, those designated to the indifference group were more affected by mood alleviation toward the purchase intention of high-priced goods rather than bulk goods. This finding could indicate the increase of unexpectedly accumulated money, which signified that people could afford to buy high-priced goods such as luxury items that they could rarely purchase before the COVID-19 outbreak (Malhotra, 2021; Phillips, 2021). In particular, the Korean government enforced certain social distancing rules because of the second propagation of COVID-19; thus, people had no choice but to spend most of their time indoors. Such restricted circumstances compelled people to increase online shopping (Yoon, 2020). Meanwhile, mood alleviation only affected the intention of purchasing high-priced goods in the depression group. These results suggest that mood alleviation can be a great shopping motivation when a person is despondent (Kang and Johnson, 2011): specifically, buying high-priced goods alleviates one's mood. This conclusion is supported by the findings of previous investigations reporting that individuals purchase expensive artistic goods (e.g., music and designer products) to alleviate the negative emotions they feel in adverse circumstances such as disasters (Kennett-Hensel et al., 2012).

Notably, the motive for shopping enjoyment did not affect the intention to purchase high-priced products and hoard daily necessities in any group. Under normal circumstances, shopping is highly associated with the feeling of pleasure. However, because of the unusual global disaster of COVID-19, people found it problematic to seek pleasure and enjoyment through the purchase of goods. The shopping enjoyment motivation is particularly linked to the feeling of pleasure. Consumer decision-making is greatly influenced by pleasure, and this high arousal in unpleasant situations seems to avoid certain behaviors (Hagtvedt and Patrick, 2008, Szymkowiak et al., 2021). Accordingly, in the unpleasant, insecure situation of COVID-19, the members of all the groups, whether anxious, angry, depressed, or indifferent toward the pandemic, did not seek pleasure through shopping.

Finally, the self-control-seeking motivation did not exert a significant impact on the purchase intentions of the anxiety, depression, and indifference groups, but the anger group was positively influenced vis-à-vis the bulk buying intention. This outcome disclosed that buying bulk products at low prices helped the members of the anger group gain self-control. Conversely, self-control-seeking did not apply a significant effect on the anxiety, depression, and indifference groups, a finding that is consistent with the reports of previous studies that stress and loss of control in indeterminate situations are positively associated with shopping attitudes (Sneath et al., 2009). This outcome is also linked to the varied perceptions of negative situations such as disasters depending on the specific emotions. For example, fear makes people tend to view negative situations as unpredictable and uncontrollable, resulting in less risk-taking behavior (Lerner and Keltner, 2001, Szymkowiak et al., 2021). Moreover, it is difficult for depressed people to develop the willingness to do something new (von dem Knesebeck et al., 2013). Depression encompasses feelings of sadness, loneliness, and loss of interest, so the desire to gain self-control through shopping may not emerge in people designated to the depression group. Meanwhile, those indifferent to the COVID-19 crisis may also not be highly aroused by certain situations. In turn, they may not feel the need to exert self-control. However, angry people tend to think of negative situations as predictable and under one's control (Szymkowiak et al., 2021). Thus, they take actions that may be risky. Therefore, the self-control motive significantly influenced shopping attitudes only in the anger group.

6. Conclusion

During the COVID-19 outbreak, people have been trying to prevent infection from the virus by voluntarily social distancing and not going outside. This study investigated how negative feelings stemming from this situation are relieved through shopping. The results of this study reveal that the socialization seeking motivation affects the intentions of all four established groups to buy high-priced goods. Moreover, the mood alleviation motivation influenced intentions to buy high-priced goods in the anxiety, depression, and indifference groups but did not affect the anger group's intentions to buy either high-priced or bulk goods. The enjoyment motivation did not affect any of the groups, and the self-control-seeking motivation only displayed a significant relationship with the intentions of the anger group to buy goods in bulk.

This study provides the following academic implications. First, this study investigated both panic buying and revenge spending that have been witnessed during COVID-19. Previous studies on shopping behaviors during disasters have mainly centered on panic buying which indicates the stockpiling of items of daily necessities such as toilet paper, canned food, masks, and hand sanitizers (Islam et al., 2021; Naeem, 2021; Omar et al., 2021; Prentice et al., 2020; Yuen et al., 2020). However, “revenge shopping” is also observed in the present pandemic situation: consumers aggressively purchase high-priced designer products or art pieces and pay for services such as massages or skin-care treatments. Some people even wait in long queues for branded products at department stores. The media have addressed the behavior of revenge shopping, but this phenomenon is under-studied in academic research. Thus, it is worthwhile to expand the scope of buying behaviors during the pandemic from panic buying (e.g., buy bulk of necessities) to revenge spending (e.g., buy high-priced goods). Second, the current study has attempted to investigate new shopping motivations that are appropriate for COVID-19 besides the mainstream shopping motivations: hedonic and utilitarian (Babin et al., 1994; Scarpi et al., 2014; Wagner and Rudolph, 2010). Under a distressful situation such as COVID-19, people experience negative feelings. It is challenging to explicate that hedonic and utilitarian shopping motivations are influenced by those negative feelings unlike other general shopping contexts including online or offline shopping (Babin et al., 1994; Scarpi et al., 2014). Thus, this study explored and selected shopping motivations (e.g., mood alleviation, shopping enjoyment, socializing, and self-control seeking) that can appropriately explain the COVID-19 context. In turn, the present study's findings can be helpful to investigate how individual feelings affect shopping motivations during COVID-19. Third, this study investigated how shopping motivations vary based on different negative feelings caused by COVID-19. Previous disaster-related shopping studies have mainly focused on how fear and anxiety affect shopping behaviors (Addo et al., 2020; Larson and Shin, 2018). For example, online shopping extremely increased due to fear of infection (Forbes, 2017; Guthrie et al., 2021), and people hoard cheap daily necessities because of fear from uncertainty caused by disasters (Islam et al., 2021; Naeem, 2021; Omar et al., 2021; Prentice et al.,2020; Yuen et al., 2020). However, because COVID-19 has lasted for a much longer time than other disasters, and people must keep social distancing, people experience more negative emotions such as anxiety, fear, depression, boredom, and anger rather than merely fear and anxiety. People feel anxious about infection, and social distancing and uncertainty make them depressed, bored, and even angry because they do not know for certain when the pandemic will end. Moreover, the survey used in this study was conducted in August 2020, when the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Korea increased by over 4000 in one month. The questionnaire responses were promptly sought during this period because of the high public awareness of the COVID-19 risk at that time.

This study also offers managerial implications for practitioners. The world has not experienced such a crisis of viral infections since the beginning of the 21st century (WHO, 2021). In fact, the outbreak of COVID-19 had a tremendous impact on small businesses (Bartik et al., 2020; Liguori and Pittz, 2020) because people were not allowed to socialize face-to-face and had to stay at home. Thus, it has made small businesses financially fragile within a short period of time. Therefore, the findings of this study can provide coping strategies for this unprecedented crisis by identifying how people deal with negative emotions during crises. Moreover, knowing how such emotions affect shopping motivations and eventually shopping behavior can help industry mangers come up with practical and tactical marketing strategies to increase customer engagements.

However, despite this study's contributions, it has five limitations. First, this study did not confirm the difference between in-store shopping and online shopping. In the case of in-store shopping, fear of infection can affect shopping motivation, and people can easily buy bulk shopping at online shopping. Therefore, future studies can further investigate this difference. Second, this study divided the negative emotions from COVID-19 into four groups. However, anxiety and depression are mental illnesses that individuals experience chronically. For example, those who already have mental illness could feel more anxious and depressed during the COVID-19 situation (Joensen et al., 2020). Therefore, we must distinguish them and examine separately. Third, this study could have analyzed the results using multi-group analysis. However, the results of confirmative factor analysis were not meet the acceptable range of measures such as TLI, CFI, or RMSEA. If it meets the standard, the analysis could have enriched. Fourth, this study investigated only the Korean context. As the COVID-19 situation varies from country to country and region to region, analyses of comparative data compared could lead to interesting findings. Lastly, our model is designed to test the mechanism from shopping motivation, through intention, and to actual shopping behavior, it is not necessary to check the reverse (or dynamic) endogeneity. The correlation between four dimensions of the shopping motivation cannot also be a huge issue for a bias of the estimation since motivation variables (Mood alleviation, Shopping enjoyment, Socializing seeking, Self-control seeking) are theoretically assumed and confirmed to be orthogonal from the hitherto studies. However, our model is not perfectly free from the omitted variable bias. In the future studies, it is possible to find another dimension of the shopping motivation during the crisis.

Declarations of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the NRF (No. 2020S1A5A8045556, 2020R1F1A1048202).

Footnotes

For example, the perception of risks is different according to cultural worldviews (e.g., hierarchist, egalitarian, individualist, and fatalist); hence, people belonging to different cultures respond differently to risks (Douglas and Wildavsky, 1982).

Appendix A. Items for the five emotions

| Construct | Source | Items |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Cella et al. (2007); Harper et al. (2020) | I am nervous about COVID-19. |

| I am anxious about COVID-19. | ||

| I am worried because of COVID-19. | ||

| I feel anxious about COVID-19. | ||

| I feel tense about COVID-19. | ||

| Fear | Ahorsu et al. (2020) | I am afraid of COVID-19 these days. |

| I am uncomfortable when I think about COVID-19. | ||

| I am afraid that I will lose my daily life because of COVID-19. | ||

| I feel fear when I hear news and stories related to COVID-19 on social media. | ||

| I am worried that I will get COVID-19, so sleeping is difficult. | ||

| Boredom | Fahlman et al. (2013); Farmer and Sundberg (1986) | There are times when I get bored after the COVID-19 outbreak. |

| I have been feeling bored since the COVID-19 outbreak. | ||

| I feel frustrated because I have not been able to get out well since the COVID-19 outbreak. | ||

| I am frustrated after the COVID-19 outbreak and I want to do something more exciting. | ||

| I feel disconnected from the world since the COVID-19 outbreak. | ||

| Depression | Cella et al. (2007); Harper et al. (2020) | I am often sad after the COVID-19 outbreak. |

| There are times when I feel depressed after the COVID-19 outbreak. | ||

| There are times when I am unhappy after the COVID-19 outbreak. | ||

| I feel like I have nothing to look forward to since the COVID-19 outbreak. | ||

| I feel like I am worthless since the COVID-19 outbreak. | ||

| Anger | Spielberger et al. (1985) | I am annoyed by COVID-19. |

| I am angry because of COVID-19. | ||

| There are times when I get angry with COVID-19 and want to swear. | ||

| I feel upset about COVID-19 and I am going to burst into my stomach. | ||

| There are times when I get angry with COVID-19 and want to yell at others. |

Appendix B. Descriptive statistics of all respondents

| Frequency | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 582 | 49.57% |

| Female | 592 | 50.43% | |

| Age (years) | 20–29 | 205 | 17.46% |

| 30–39 | 228 | 19.42% | |

| 40–49 | 259 | 22.06% | |

| 50–59 | 275 | 23.42% | |

| 60–69 | 207 | 17.63% | |

| Education level | Under high school | 164 | 13.97% |

| University student | 69 | 5.88% | |

| Bachelor's degree | 816 | 69.51% | |

| Over graduate student | 125 | 10.65% | |

| Annual income (million wona) | Under 25 | 319 | 27.17% |

| 25–30 | 228 | 19.42% | |

| 30–50 | 355 | 30.24% | |

| 50–100 | 245 | 20.87% | |

| over 100 | 27 | 2.30% | |

aAs of February 26, 2021, 1 USD is 1122.40 KRW.

Appendix C. Survey items

| Construct | Source | Code | Items |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mood alleviation | Kang and Johnson (2011) | Mood1 | Shopping is an escape from loneliness. |

| Mood2 | Shopping for something new fills an empty feeling. | ||

| Mood3 | Shopping is a way to take my mind off things that are bothering me. | ||

| Mood4 | Shopping is a way to remove myself from stressful environments. | ||

| Mood5 | Shopping is a way to control my situation when other things seem out of control. | ||

| Shopping enjoyment | Latorre Roman et al. (2014) | Enjoy1 | I enjoy shopping. |

| Enjoy2 | Shopping helps me relax. | ||

| Enjoy3 | Shopping gives me energy. | ||

| Socialization seeking | Brown et al. (1993); Dey and Srivastava (2017) | Social1 | When shopping, I take time to interact with other people. |

| Social2 | I want to get responses from other people for my shopping. | ||

| Social3 | The reaction of friends or family influences my shopping activities. | ||

| Social4 | I like to see my friends or family shopping. | ||

| Self-control seeking | Maas et al. (2017) | Control1 | After a hard day's work, I often feel that I deserve to do shopping. |

| Control2 | When I feel bad I think that shopping will help me to feel better for a moment. | ||

| Control3 | I know that shopping will help me overcome negative emotions. | ||

| Control4 | When I feel sad, I expect that shopping will comfort me. | ||

| Control5 | When I feel miserable, I think that I would do myself a favor by shopping because it will make me feel better for a while. | ||

| Intention in high-priced goods purchase | Revised based on Zhang and Kim (2013) | High intention 1 | In the future, I am willing to purchase products at a higher price than I usually buy. |

| High intention 2 | I intend to buy a product at a higher price than I usually buy in six months. | ||

| High intention 3 | I will continue to buy expensive products. | ||

| High intention 4 | I am interested in purchasing products that are more expensive than usual. | ||

| Intention in bulk goods purchase | Revised based on Zhang and Kim (2013) | Bulk intention 1 | I will continue to buy more products than usual in the future. |

| Bulk intention 2 | I plan to buy more products at a price similar to what I usually buy. | ||

| Bulk intention 3 | I will continue to buy many products at once even if I do not need it now. | ||

| Bulk intention 4 | I will buy more of the type of items I usually buy. | ||

| Actual high-priced goods purchase | Revised based on Zhang and Kim (2013) | High purchase 1 | In the last six months after the onset of COVID-19, I have purchased a product at a price higher than I would normally pay. |

| High purchase 2 | In the last month, I have purchased a product at a price higher than I would normally pay. | ||

| High purchase 3 | After the outbreak of COVID-19, I bought an expensive product. | ||

| High purchase 4 | Since COVID-19 began, I have become interested in purchasing products that are more expensive than usual. | ||

| Actual bulk goods purchase | Revised based on Zhang and Kim (2013) | Bulk purchase 1 | In the last 6 months after the onset of COVID-19, I have bought more products than usual. |

| Bulk purchase 2 | I have bought more products at a price level similar to what I normally buy in the last month. | ||

| Bulk purchase 3 | Since COVID-19 began, I have bought more of the type of items I usually buy. | ||

| Bulk purchase 4 | Since COVID-19 began, I have bought several products at once even though I do not need them now. |

Appendix D. SEM results of each group

Fig. D1.

SEM results for the anxiety group.

Fig. D2.

SEM results for the anger group.

Fig. D3.

SEM results for the depression group.

Fig. D4.

SEM results for the indifferent group.

References

- Abdalla C.C., Zambaldi F. Ostentation and funk: an integrative model of extended and expanded self theories under the lenses of compensatory consumption. International Business Review. 2016;25(3):633–645. [Google Scholar]

- Addo P.C., Jiaming F., Kulbo N.B., Liangqiang L. COVID-19: fear appeal favoring purchase behavior towards personal protective equipment. The Service Industries Journal. 2020;40(7-8):471–490. [Google Scholar]

- Ahorsu D.K., Lin C.Y., Imani V., Saffari M., Griffiths M.D., Pakpour A.H. The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I., Fishbein M. Prentice-Hall; NJ: 1980. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Archimi C.S., Reynaud E., Yasin H.M., Bhatti Z.A. How perceived corporate social responsibility affects employee cynicism: the mediating role of organizational trust. Journal of Business Ethics. 2018;151(4):907–921. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold M.J., Reynolds K.E. Hedonic shopping motivations. Journal of Retailing. 2003;79(2):77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Atalay A.S., Meloy M.G. Retail therapy: a strategic effort to improve mood. Psychology & Marketing. 2011;28(6):638–659. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın G. Do personality traits and shopping motivations affect social commerce adoption intentions? Evidence from an emerging market. Journal of Internet Commerce. 2019;18(4):428–467. [Google Scholar]

- Babin B.J., Darden W.R., Griffin M. Work and/or fun: measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of consumer research. 1994;20(4):644–656. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi R.P., Yi Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 1988;16:74–94. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S.J. Understanding terror states of online users in the context of COVID-19: an application of Terror Management Theory. Computers in Human Behavior. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106967. 106967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartik A.W., Bertrand M., Cullen Z., Glaeser E.L., Luca M., Stanton C. The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020;117(30):17656–17666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006991117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P.M., Bonett D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88(3):588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Blalock H.M. In: Causal Models in the Social Sciences. Blalock H.M., editor. Aldine; Chicago: 1971. Causal models involving unobserved variables in stimulus-response situations; pp. 335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhausen G.V., Sheppard L.A., Kramer G.P. Negative affect and social judgement: the differential impact of anger and sadness. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1994;24(1):45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. 10227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G., Boya U.O., Humphreys N., Widing R.E., II Attributes and behaviors of salespeople preferred by buyers: high socializing vs. low socializing industrial buyers. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management. 1993;13(1):25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Browne M.W., Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research. 1992;21(2):230–258. doi: 10.1177/0049124192021002005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]