Abstract

The main protease (Mpro) is a validated antiviral drug target of SARS-CoV-2. A number of Mpro inhibitors have now advanced to animal model study and human clinical trials. However, one issue yet to be addressed is the target selectivity over host proteases such as cathepsin L. In this study we describe the rational design of covalent SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors with novel cysteine reactive warheads including dichloroacetamide, dibromoacetamide, tribromoacetamide, 2-bromo-2, 2-dichloroacetamide, and 2-chloro-2, 2-dibromoacetamide. The promising lead candidates Jun9-62-2R (dichloroacetamide) and Jun9-88-6R (tribromoacetamide) had not only potent enzymatic inhibition and antiviral activity, but also significantly improved target specificity over caplain and cathepsins. Compared to GC-376, these new compounds did not inhibit the host cysteine proteases including calpain I, cathepsin B, cathepsin K, cathepsin L, and caspase-3. To the best of our knowledge, they are among the most selective covalent Mpro inhibitors reported thus far. The co-crystal structures of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with Jun9-62-2R and Jun9-57-3R reaffirmed our design hypothesis, showing that both compounds form a covalent adduct with the catalytic C145. Overall, these novel compounds represent valuable chemical probes for target validation and drug candidates for further development as SARS-CoV-2 antivirals.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, main protease, cysteine warhead, antiviral

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is a timely reminder that direct-acting antivirals are urgently needed. Despite the expeditious development of mRNA vaccines, SARS-CoV-2 is likely to remain a significant public health concern in the foreseeable future for several reasons. First, variant viruses with escape mutations continue to emerge, which compromise the efficacy of vaccines.1 Second, a portion of the population opt out of vaccination based on their religious beliefs, concerns of long-term side effects or other reasons. As such, it is unpredictable when or whether herd immunity can be achieved. Third, the durability of COVID vaccines is currently unknown. Therefore, antivirals are important complements of vaccines to combat both current COVID-19 pandemic and future coronavirus outbreaks.

In combating the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers from different disciplines work relentlessly to discover countermeasures. Drug repurposing led to the identification of remdesivir as the first FDA-approved SARS-CoV-2 antiviral. EIDD-2801, another viral polymerase inhibitor discovered through a similar approach, is in human clinical II/III trials.2 Among the drug targets exploited, the viral polymerase including the main protease (Mpro) and the papain-like protease (PLpro) are the most extensively studied.3 The Mpro is a cysteine protease and digests the viral polyprotein at more than 11 sites during the viral replication. Mpro functionas as a dimer and has a unique preference for glutamine at the substrate P1 position. Mpro is a validated high-profile antiviral drug target and Mpro inhibitors have demonstrated potent antiviral activity in cell cultures and animal models (Figure 1).4–8 Two Pfizer Mpro inhibitors PF-07304814 and PF-07321332 are advanced to phase I clinical trial.9–10 Additional promising leads are listed in Table 1, which are in different stages of translational development. The success of fast-track development of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors is a result of accumulated expertise and knowledge in targeting SARS-CoV Mpro and similar picornavirus 3C-like (3CL) proteases over the years.11 Despite the tremendous progress in developing Mpro inhibitors, the selectivity profiling has thus far been largely neglected. It is essential to address the target selectivity issue early on to avoid catastrophic failures in the later clinical studies. Cysteine protease inhibitor has yet received FDA approval, and the lack of target specificity might be the culprit.

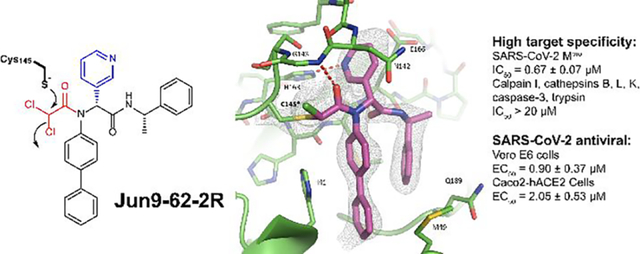

Figure 1.

Advanced SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors with translational potential.

Table 1.

Target specificity of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors.

| Compound | SARS-CoV-2 Mpro IC50 (nM) |

Cathepsin L IC50 (nM) |

Additional off targets | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC-376 | 33 | 0.99 | Calpain I (IC50 = 74 nM) Cathepsin K (IC50 = 0.56 nM) |

8, 17–18, 20, 24 |

| MPI8 | 105 | 1.2 | Cathepsin B (IC50 = 230 nM) Cathepsin K (IC50 = 180 nM) |

15–16 |

| PF-00835231 | 5 | 146 | Cathepsin B (IC50 = 1.3 μM) | 19, 21 |

| 6e | 10 | < 0.5 | - | 19, 22 |

| 6j | 7 | < 0.5 | - | 19, 22 |

| 11a | 8 | 0.21 | - | 19, 23 |

The majority of current reported SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors are peptidomimetic covalent inhibitors with a reactive warhead such as ketone, aldehyde or ketoamide.11 Some of the promising examples include the Pfizer compounds PF-07304814 (the parent compound PF-00835231),10 11a,12 GC-376,7, 13 the deuterated GC-376 (D2-GC-376),5 6e, 6j,14 MI-09, MI-30,4 and MPI815 (Figure 1). Although the high reactivity of these reactive warheads, especially the aldehyde, confers potent activities in the enzymatic assay and antiviral assay, it inevitably leads to off-target side effects through reacting with some host proteins.16–19 For example, we and others have shown that GC-376 is a potent inhibitor of cathepsin L (Table 1).17, 20 A recent study revealed that MP18, an analog of GC-376 with an aldehyde warhead, inhibits cathepsins B, L, and K with IC50 values of 1.2, 230, and 180 nM, respectively.15 The off-target effect is also a potential concern for some of the most advanced Mpro inhibitors including the clinical candidate PF-07304814,21 compounds 6j and 6e which showed in vivo antiviral efficacy against MERS-CoV-2 infection in mice,22 and compound 11a with potent in vitro antiviral activity (Table 1).23 All of these compounds are potent inhibitors of cathepsin L. The high reactivity of the aldehyde warhead might confer the lack of target specificity, and the design of covalent inhibitors with a high target specificity remains a daunting task.

We report herein the rational design of covalent Mpro inhibitors with novel cysteine reactive warheads and high target specificity. Specifically, guided by the X-ray crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with 23R (Jun8–76-3A) (PDB: 7KX5), which was one of the most potent noncovalent Mpro inhibitors developed from our earlier study,24 we systematically explored a number of novel electrophiles in replacement of the P1’ furyl substitution in 23R. The aim is to identify C145 reactive electrophiles with both potent Mpro inhibition and high target selectivity. This effort led to the discovery of several novel cysteine reactive warheads including dichloroacetamide, dibromoacetamide, tribromoacetamide, 2-bromo-2, 2-dichloroacetamide, and 2-chloro-2, 2-dibromoacetamide. One of the most potent lead compounds Jun9-62-2R (dichloroacetamide) inhibited SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with an IC50 of 0.43 μM and viral replication with an EC50 of 2.05 μM in Caco2-hACE2 cells. Significantly, unlike GC-376, Jun9-62-2R (dichloroacetamide) and Jun9-88-6R (tribromoacetamide) are highly selective toward Mpro and do not inhibit the host calpain I, cathepsins B, K, L, caspase-3, and trypsin. X-ray crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with Jun9-62-2R (dichloroacetamide) and Jun9-57-3R (chloroacetamide) revealed that the C145 forms a covalent adduct with the reactive warheads. Overall, the discovery of these di- and trihaloacetamides as novel cysteine reactive warheads shed light on feasibility of developing SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors with high target specificity over tested calpain and cathepsins and cellular selectivity index. These novel compounds represent valuable chemical probes for target validation and drug candidates for further development as SARS-CoV-2 antivirals.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis of covalent Mpro inhibitors.

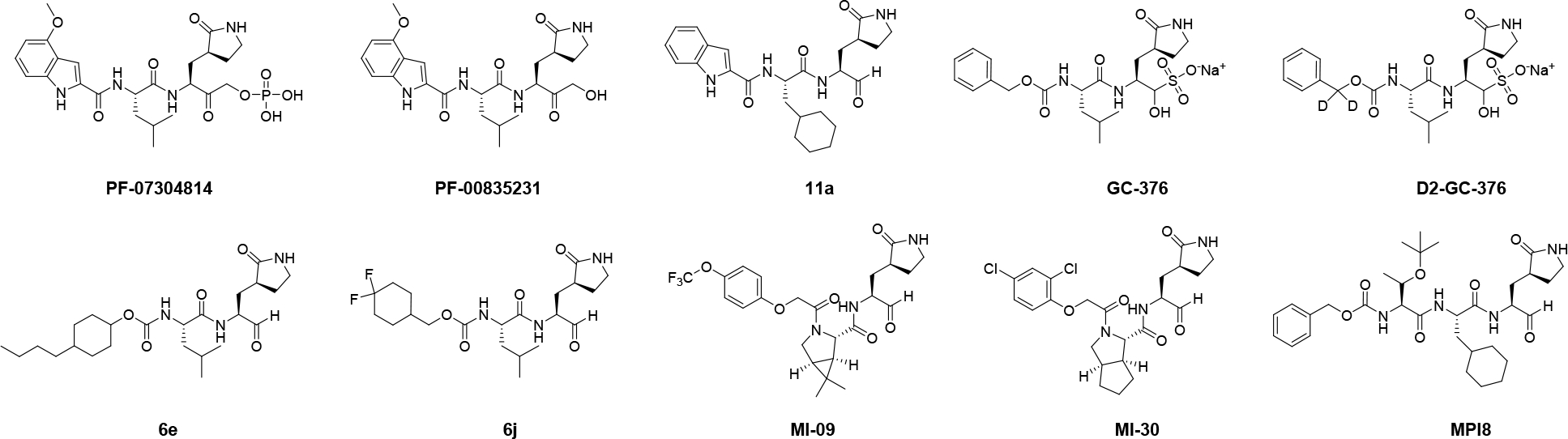

The covalent Mpro inhibitors were synthesized by the one-pot Ugi four-component reaction (Ugi-4CR) as shown for Jun9-62-2 (Figure 2) with yields from 33% to 88%. For compounds with potent enzymatic inhibition, the diastereomers were subsequently separated by chiral HPLC. The absolute stereochemistry of Jun9-57-3R and Jun9-62-2R was determined by X-ray crystallography, and the stereochemistry for the diastereomers of Jun9-90-4, Jun9-89-2, Jun9-89-4, and Jun9-88-6 were tentatively assigned based on their relevant retention time in chiral HPLC.

Figure 2.

Synthesis route for the covalent SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors through Ugi-4CR. The R and S chirality refers to the chiral center at the pyridine substitution.

Rational design of covalent Mpro inhibitors.

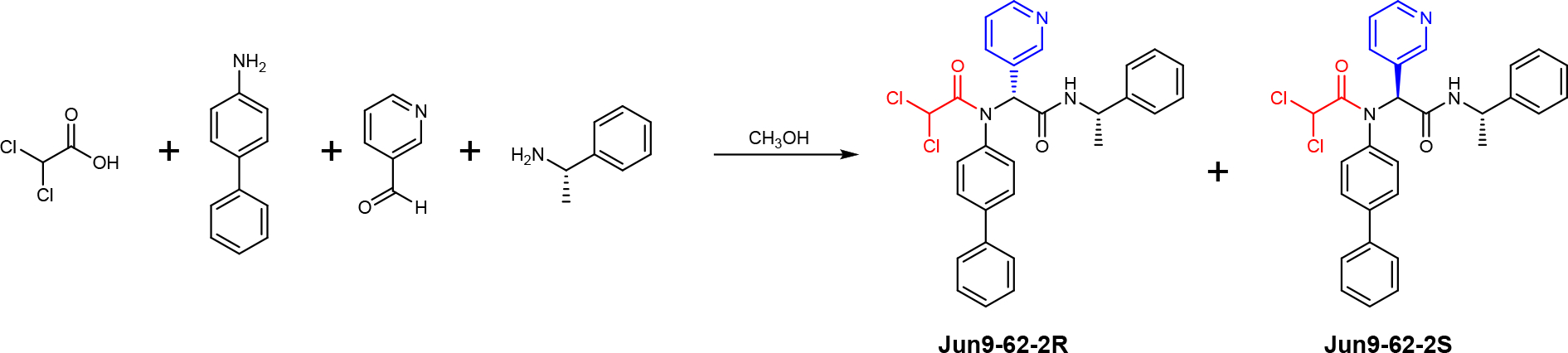

23R was designed based on the superimposed X-ray crystal structure of GC-376 with ML188 and UAWJ254.24–25 The X-ray crystal structure showed that the furyl substitution at the P1’ position of 23R is in close proximity with the catalytic cysteine 145 (3.4 Å between C145 sulfur and the C-2 carbon of furyl, PDB: 7KX5) (Figure 3A), suggesting replacement of furyl with a reactive warhead might lead to covalent inhibitors (Figure 3B). 23R is an ideal lead candidate for the design of covalent Mpro inhibitors for several reasons: 1) the P1, P2, and P3 substitutions have already been optimized; 2) the designed compounds can be expeditiously synthesized by the one-pot Ugi-4CR; and 3) a diverse of cysteine reactive warheads are commercially available and can be promptly introduced at the P1’ position to react with the C145.

Figure 3.

Rational design of covalent SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors based on 23R. (A) X-ray crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with 23R (PDB: 7KX5). The distance between the furyl ring and the catalytic cysteine 145 is 3.4 Å. (B) Representative cysteine reactive warheads for covalent labeling of C145. (C) FDA-approved covalent inhibitors. The reactive warheads are colored in magenta. Pfizer compound 12 is a preclinical candidate. (D) Designed covalent SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors. The results are average ± standard deviation of three repeats.

Although a number of thiol-reactive warheads have been exploited in the development of covalent protease and kinase inhibitors,26–28 we decided to focus on pharmacologically compliant reactive warheads from the FDA-approved drugs. The majority of FDA-approved thiol-reactive drugs are kinase inhibitors including ibrutinib, osimertinib, zanubrutinib, acalabrutinib, dacomitinib, neratinib, and afatinib (Figure 3C).26 As such, acrylamide and 2-butynamide were chosen as reactive warheads in our initial design of covalent SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors (Figure 3B). Chloroacetamide was also chosen as it was previously explored by Pfizer for the development of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors (Pfizer compound 12) (Figure 3C).21 Chloroacetamide is frequently used as a reactive warhead for designing chemical probes for target pull down.29 Finally, we included azidomethylene as it was previously shown to be a relatively unreactive cysteine warhed.30–31 The fluoroacetamide was included as a control.

The designed covalent SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors were shown in Figure 3D. All compounds were first tested in the FRET-based Mpro enzymatic assay. Active hits were further tested for cellular cytotoxicity to select candidates for the following antiviral assay against SARS-CoV-2. It was found that the azidoacetamide Jun9-61-1 and the fluoracetamide Jun9-61-4 were not active (IC50 > 20 μM). Surprisingly, the acrylamides Jun10–15-2 and Jun9-51-3 were also not active (IC50 > 20 μM), suggesting the acrylamide might not be positioned at the right geometry for reacting with the C145. Gratifyingly, Jun9-62-1 with the 2-butynamide warhead showed potent inhibition with an IC50 of 1.15 μM. However, Jun9-62-1 also had moderate cytotoxicity in both Vero E6 (CC50 = 17.99 μM) and Calu-3 (CC50 = 47.77 μM) cells. Similarly, covalent inhibitors with the chloroacetamide reactive warhead had potent inhibition against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. The most potent compound Jun9-57-3R inhibited SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with an IC50 of 0.05 μM, comparable to the potency of GC-376 (IC50 = 0.03 μM). Interestingly, the diastereomer Jun9-57-3S was also a potent Mpro inhibitor with an IC50 of 1.13 μM. However, covalent inhibitors with the chloroacetamide warhead Jun9-54-1, Jun9-59-1, Jun9-55-2, Jun9-57-3R, Jun9-57-3S, Jun9-57-2, and Jun9-55-1 were highly cytotoxic in Vero E6 (CC50 < 11 μM) and Calu-3 (CC50 < 2 μM) cells, possibly due to their off-target effects on host proteins/DNAs. The low cellular selectivity index precludes further development of these covalent Mpro inhibitors as SARS-CoV-2 antiviral drugs.

Exploring acrylamides and haloacetamides as novel warheads for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro C145.

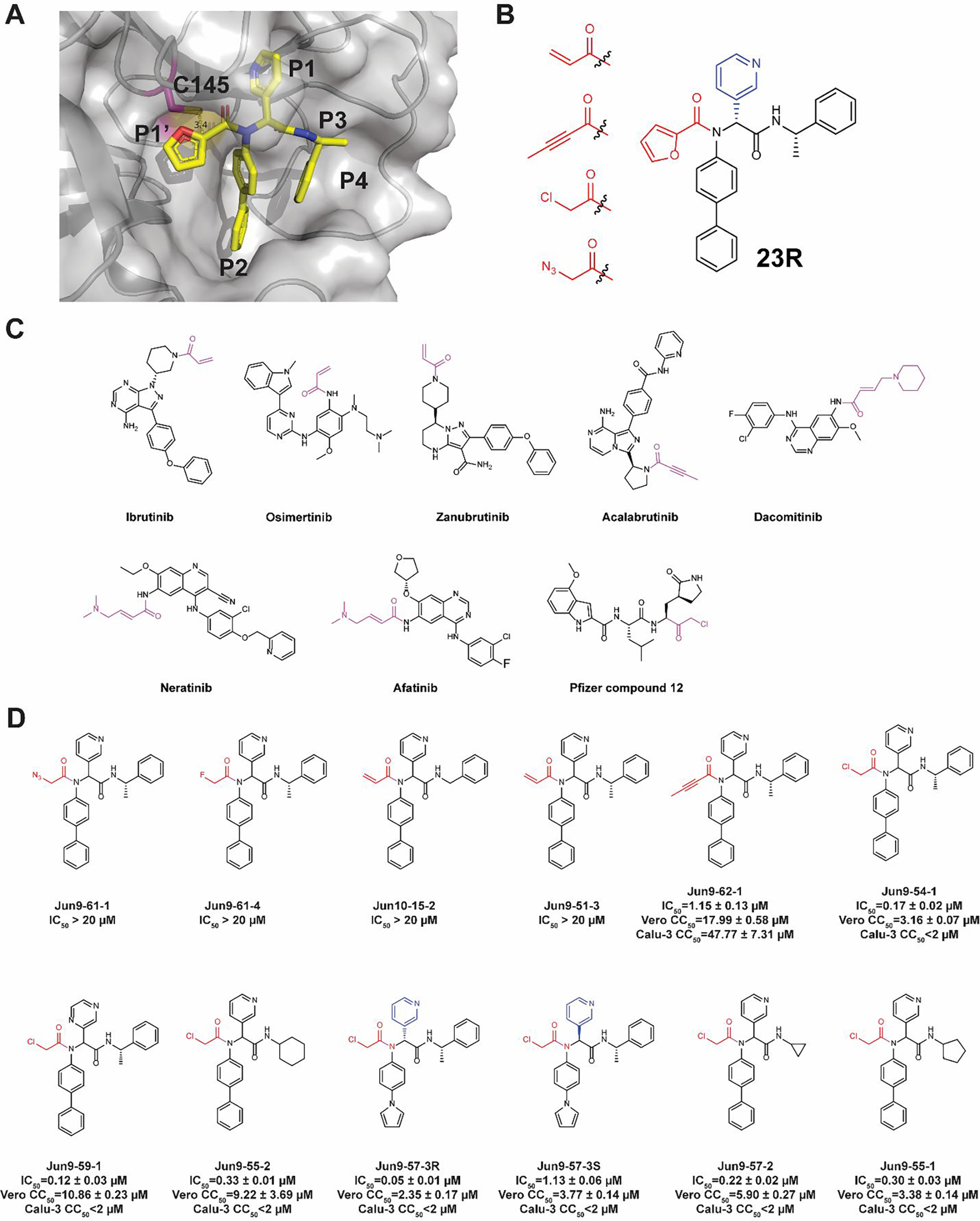

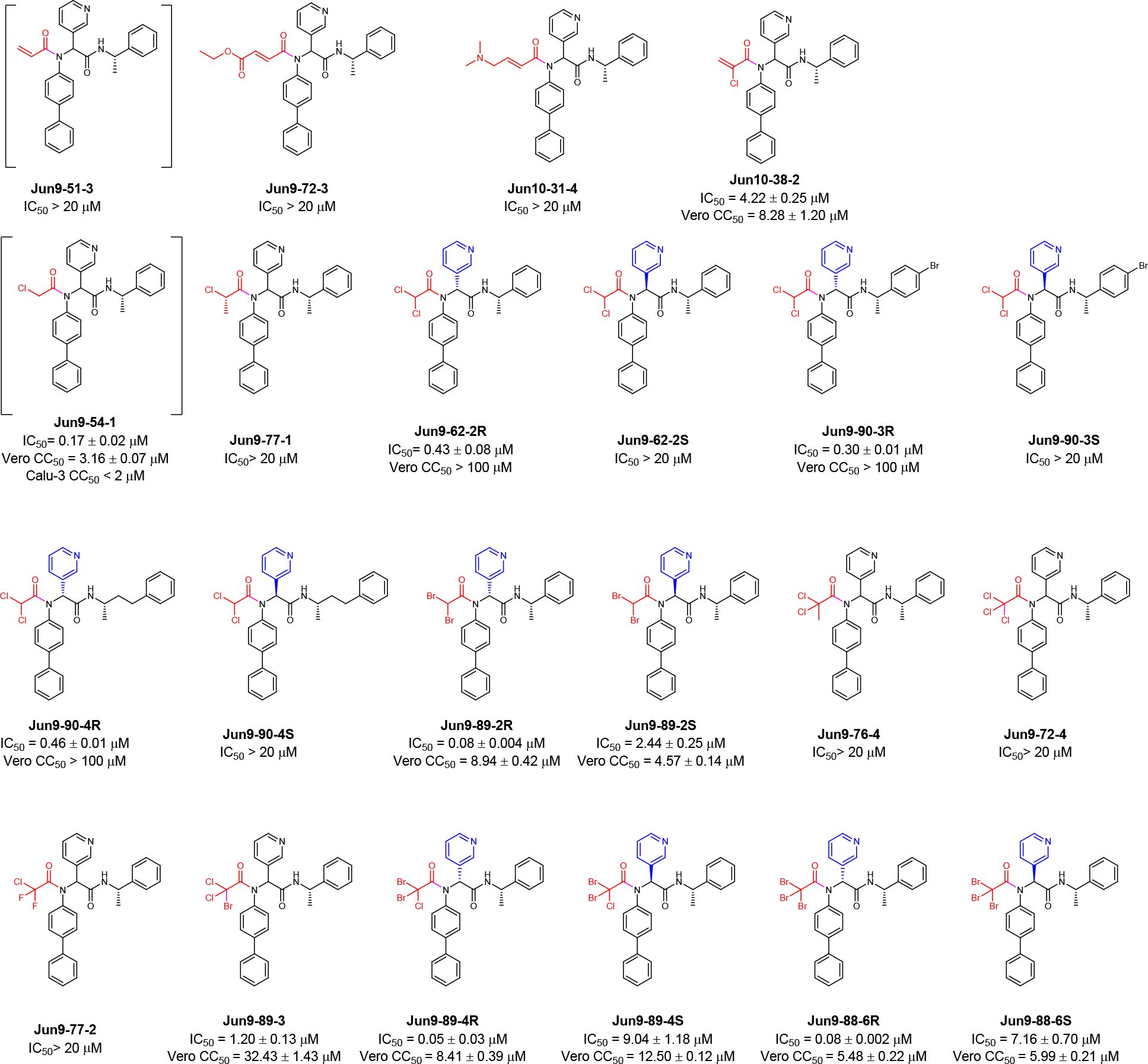

For the acrylamide series of compounds, Jun9-72-3 and Jun10–31-4, both containing a 2-substituted acrylamide warhead, were not active against Mpro (IC50 > 20 μM) (Figure 4). However, compound Jun10–38-2 with the 2-chloroacrylamide had potent inhibition with an IC50 of 4.22 μM.

Figure 4.

SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors with novel acrylamide and haloacetamide warheads. The results are average ± standard deviation of three repeats.

For the haloacetamide series of compounds, the reference compound Jun9-54-1 with the classical chloroacetamide reactive warhead had potent inhibition against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with an IC50 of 0.17 μM. However, it was cytotoxic in both Vero E6 cells and Calu-3 cells with CC50 values less than 3.5 μM. To increase the cellular selectivity index, we reasoned that substituted chloroacetamides or haloacetamides might have reduced cellular cytotoxicity while maintaining potent Mpro inhibition. It was found that Jun9-77-1 with the 2-chloropropanamide warhead was not active (IC50 > 20 μM). Encouragingly, compound Jun9-62-2R with the dichloroacetamide warhead had potent inhibition against Mpro with an IC50 of 0.43 μM while being non-cytotoxic to Vero E6 cells (CC50 > 100 μM). In comparison, the corresponding diastereomer Jun9-62-2S was not active (IC50 > 20 μM), which is consistent with the predicted binding mode (Figure 3A). Given these promising results, we further designed two additional dichloroacetamide compounds Jun9-90-3 and Jun9-90-4 with variations at the P3/P4 substitutions. Similar to Jun9-62-2R, both Jun9-90-3R and Jun9-90-4R were potent inhibitors with IC50 values of 0.30 and 0.46 μM, respectively. Both compounds were also non-cytotoxic to Vero E6 cells (CC50 > 100 μM). In contrast, the corresponding diastereomers Jun9-90-3S and Jun9-90-4S were not active (IC50 > 20 μM).

We further explored di- and trisubstituted haloacetamides as Mpro C145 reactive warheads (Figure 4). Jun9-89-2R with the dibromoacetamide warhead is highly active with an IC50 of 0.08 μM, however, the cell cytotoxicity also increased (CC50 = 8.94 μM). The diastereomer Jun9-89-2S also had potent inhibition against Mpro with an IC50 of 2.44 μM and comparable cytotoxicity (CC50 = 4.57 μM). Jun9-76-4 with the 2, 2-dichloropropanamide warhead, Jun9-72-4 with the trichloroacetamide, Jun9-77-2 with the 2-chloro-2, 2-difluoroacetamide were all inactive against Mpro (IC50 > 20 μM). Jun9-89-3 with the 2-bromo-2, 2-dichloroacetamide showed potent inhibition with an IC50 of 1.20 μM. The cytotoxicity of Jun9-89-3 also improved (CC50 = 32.43 μM). Jun9-89-4R with the 2-chloro-2, 2-dibromoacetamide warhead is highly potent with an IC50 of 0.05 μM, but it was cytotoxic in Vero E6 cells (CC50 = 8.41 μM). The diastereomer Jun9-89-4S was less active (IC50 = 9.04 μM). Jun9-88-6R with the tribromoacetamide warhead had high potency against Mpro with an IC50 of 0.08 μM, while the diastereomer Jun9-88-6S was less active (IC50 = 7.16 μM). Both Jun9-88-6R and Jun9-88-6S had comparable cytotoxicity as Jun9-54-1 with CC50 value of 5.48 and 5.99 μM, respectively.

Pharmacological characterization of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors with novel reactive warheads.

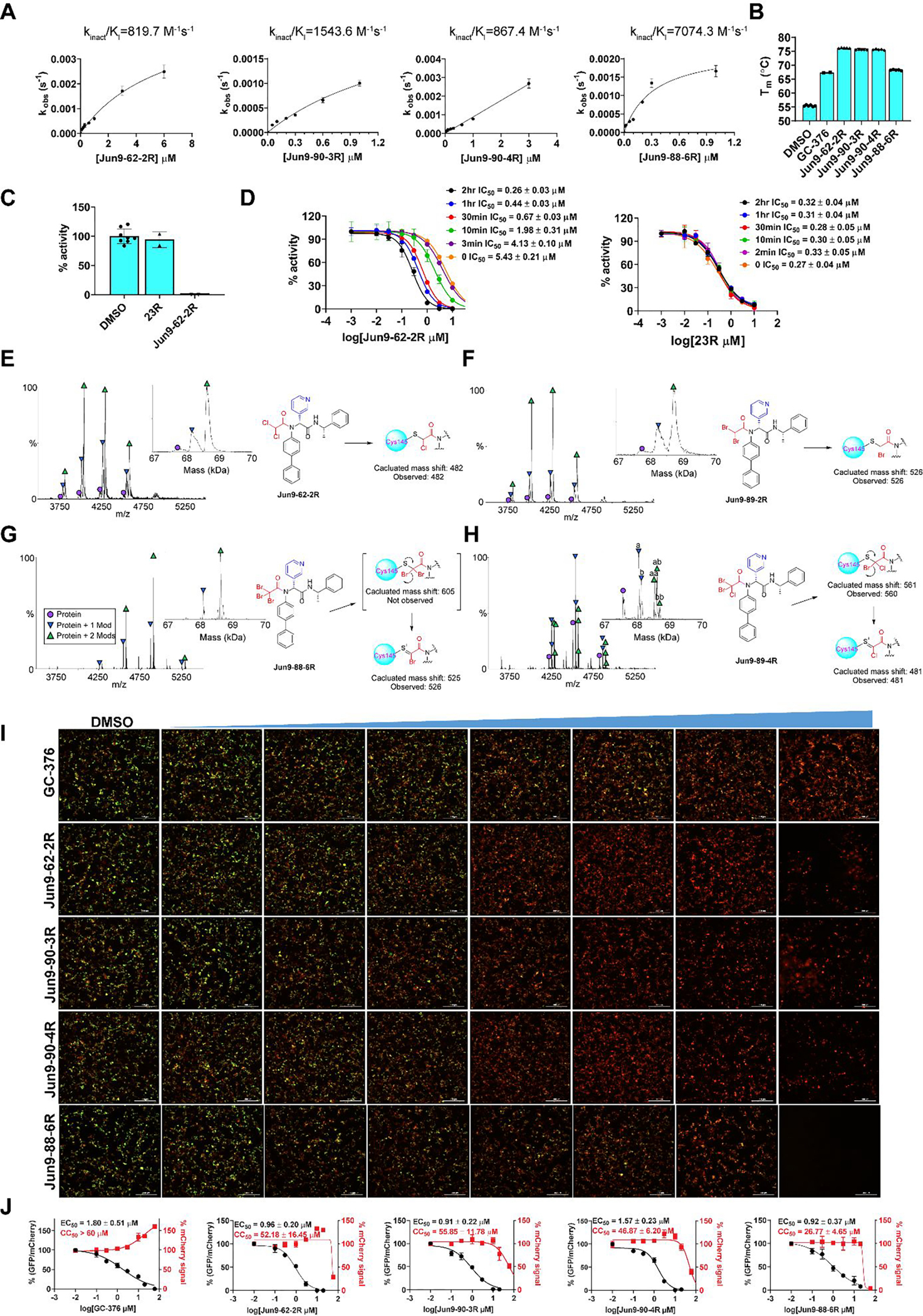

Based on the Mpro inhibition and cell cytotoxicity, four compounds Jun9-62-2R, Jun9-90-3R, Jun9-90-4R, and Jun9-88-6R were selected for mechanistic studies (Figure 5). Enzymatic kinetic studies suggested that these four compounds bind to Mpro in a two-step process: the first step reversible binding (KI) and the second step irreversible binding (kinact). The calculated kinact/KI values for Jun9-62-2R, Jun9-90-3R, Jun9-90-4R, and Jun9-88-6R were 819.7, 1543.6, 867.4, and 7074.3 M−1s−1, respectively (Figure 5A). These results were in agreement with the expected mechanism of action in which all four compounds form a covalent bond with the catalytic C145. In the thermal shift-binding assay, all four compounds stabilized the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro upon binding as reflected by the Tm shift to higher temperatures (Figure 5B). As the tribromoacetamide is sterically hindered, the mechanism of action of Jun9-88-6R might involve the nucleophilic attack of the carbonyl by the C145 thiol to give a thiohemiketal intermediate, followed by a 1,2-shift of the sulfur to displace one bromide (Figure S2).

Figure 5.

Pharmacological characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors. (A) Curve fittings of the enzymatic kinetic studies of four compounds Jun9-62-2R, Jun9-90-3R, Jun9-90-4R, and Jun9-88-6R against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. (B) Binding of four compounds Jun9-62-2R, Jun9-90-3R, Jun9-90-4R, and Jun9-88-6R to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in the thermal shift assay. (C) Fast dilution experiment. 10 μM Mpro was pre-incubated with 10 μM of testing compounds for 2 h at 30 °C; the pre-formed compound-enzyme complex was diluted 100-fold into reaction buffer before initiate the enzymatic reaction. The recovered enzymatic activity was compared with DMSO control. 23R is a non-covalent Mpro inhibitor and it was included as a control. (D) Time dependent inhibition of Mpro by Jun9-62-2R. 100 nM SARS CoV-2 Mpro was pre-incubated with Jun9-62-2R for various period of time (0 min to 2 h) before the addition of 10 μM FRET substrate to initiate the enzymatic reaction. 23R was included as a control. (E-H) Native mass spectrometry assay of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro reveals binding of Jun9-62-2R with mass modifications of 482 Da (E), Jun9-89-2R with mass modifications of 526 Da (F), Jun9-88-6R with mass modifications of 526 Da (G), and Jun9-89-4R with mass modifications of (a) 481 and (b) 561 Da (H). Mpro functions as a dimer, and both one drug per dimer (Protein + 1 Mod) and two drugs per dimer (Protein + 2 Mods) were observed. (I) FlipGFP assay characterization of the inhibition of the cellular enzymatic activity of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro by the four compounds Jun9-62-2R, Jun9-90-3R, Jun9-90-4R, and Jun9-88-6R. (J) Curve fittings of the FlipGFP Mpro assay. The results are average ± standard deviation of three repeats.

To provide additional lines of evidence to support the proposed mode of action of covalent binding, we performed three additional experiments. First, to demonstrate the reversibility of the binding of Jun9-62-2R to Mpro, we incubated 10 μM of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with 10 μM of Jun9-62-2R for 2 h and monitored the enzymatic activity of Mpro following 100-fold dilution of the mixture. It was found that no enzymatic activity was recovered (Figure 5C). In contrast, the mixture with our previously developed non-covalent inhibitor 23R showed nearly complete recovery of enzymatic activity after dilution (Figure 5C). These results suggest that the binding of Jun9-62-2R is irreversible while the binding of 23R is reversible. Second, we repeated the FRET assay of Jun9-62-2R with different pre-incubation times and found that longer pre-incubation time gave lower IC50 values (Figure 5D). This data is consistent with the mode of action of covalent inhibitors.32 In contrast, pre-incubation of Mpro with the non-covalent inhibitor 23R did not lead to significant changes of the IC50 value (Figure 5D). Third, we used native mass spectrometry to detect the covalent adducts of Mpro with Jun9-62-2R, Jun9-89-2R, Jun9-88-6R, and Jun9-89-4R. The expected mass shifts of 482 Da and 526 Da were observed for Jun9-62-2R and Jun9-89-2R, respectively (Figures 5E and F). Interesting, the expected dibromoacetamide conjugate was not observed for Jun9-88-6R, suggesting this conjugate might not be stable. Instead, the mass shift corresponding to the monobromo thiol adduct was observed (Figure 5G). For Jun9-89-4R, the mass shifts for both the chlorobromo and chloro thiol adducts were observed (Figure 5H).

To further profile the cellular Mpro inhibition, we tested these four compounds in our recently developed FlipGFP assay.18, 33 Briefly, the GFP is split into two parts, the β1–9 template and the β10–11 strands. The β10 and β11 strands were engineered with K5-E5 linker such that they are restrained in the parallel form. When the linker is cleaved by Mpro, β10 and β11 adopt antiparallel conformation, which allows association with the β1–9 template, leading to the recovery of the GFP signal. In the FlipGFP assay, GFP signal is proportional to the Mpro enzymatic activity. It was found that all four compounds led to dose-dependent inhibition of the GFP signal with EC50 values of 0.96 μM (Jun9-62-2R), 0.91 μM (Jun9-90-3R), 1.57 μM (Jun9-90-4R), and 0.92 μM (Jun9-88-6R) (Figures 5I and J). The EC50 value for the positive control GC-376 was 1.80 μM. This result suggests that these four compounds can potently inhibit the Mpro in the cellular content.

Antiviral activity of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors with novel reactive warheads.

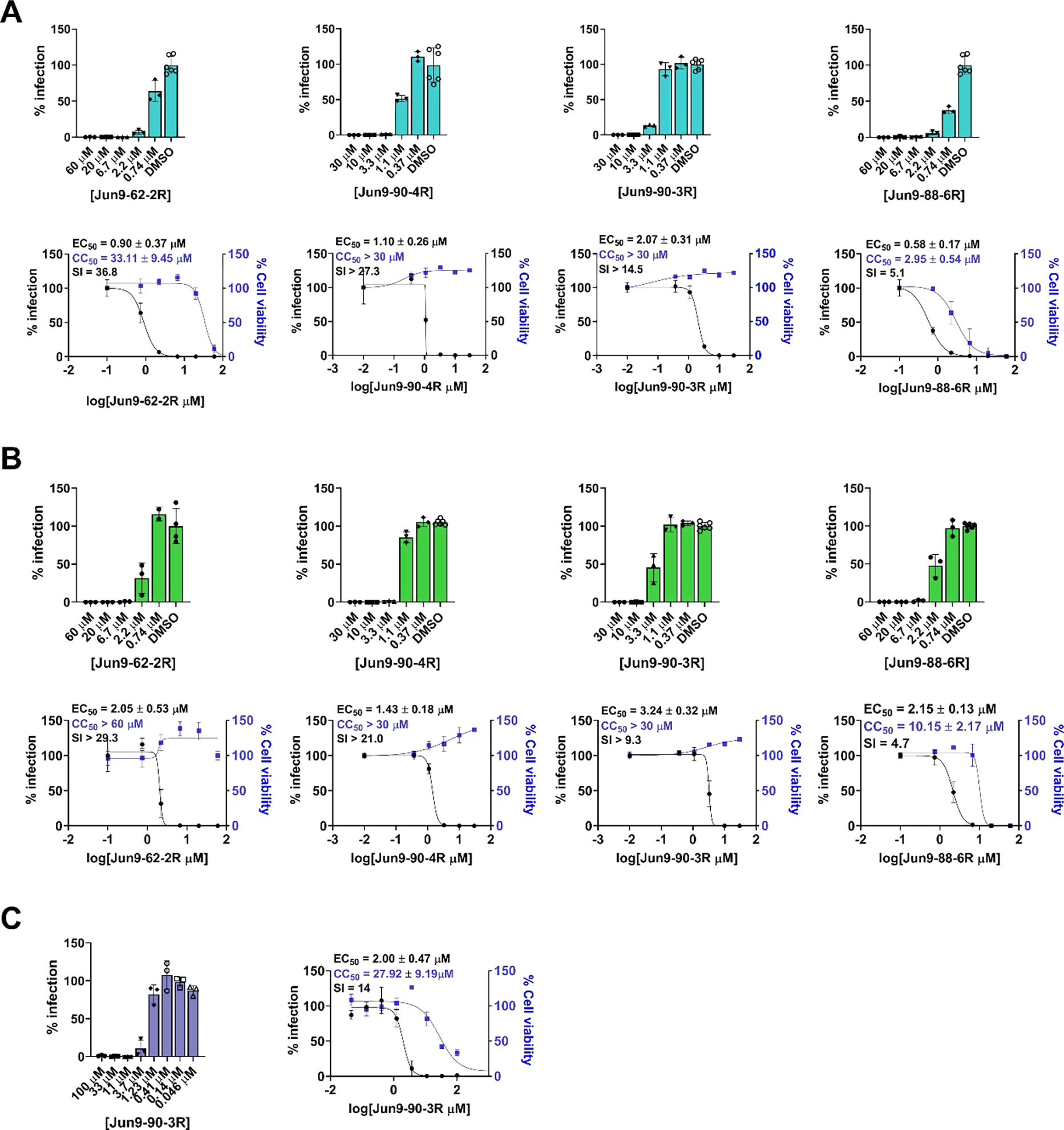

The antiviral activity of the four lead compounds was evaluated in both Vero E6 cells and Caco2-hACE2 cells to exclude cell type dependent effect. Caco2-hACE2 with endogenous TMPRSS2 expression is a validated cell line for SARS-CoV-2 antiviral assay.34–36 Jun9-62-2R, Jun9-90-3R, Jun9-90-4R, and Jun9-88-6R inhibited SARS-CoV-2 replication in Vero E6 cells with EC50 values of 0.90, 2.07, 1.10, and 0.58 μM, respectively (Figure 6A). All four compounds showed comparable antiviral activity in Caco2-hACE2 cells with EC50 values of 2.05, 3.24, 1.43, and 2.15 μM, respectively (Figure 6B). In comparison, GC-376 inhibited SARS-CoV-2 replication in Vero E6 and Caco2-hACE2 cells with EC50 values of 1.51 and 2.90 μM. When tested in Calu-3 cells, Jun9-90-3R showed comparable antiviral activity with an EC50 value of 2.00 μM (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Antiviral activity of Jun9-62-2R, Jun9-90-3R, Jun9-90-4R, and Jun9-88-6R against SARS-CoV-2 in different cell lines. (A) Antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 in Vero E6 cells. (B) Antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 in Caco2-hACE2 cells. (C) Antiviral activity of Jun9-90-3R in Calu-3 cells. The results are average ± standard deviation of three repeats.

Profiling the target selectivity against host proteases.

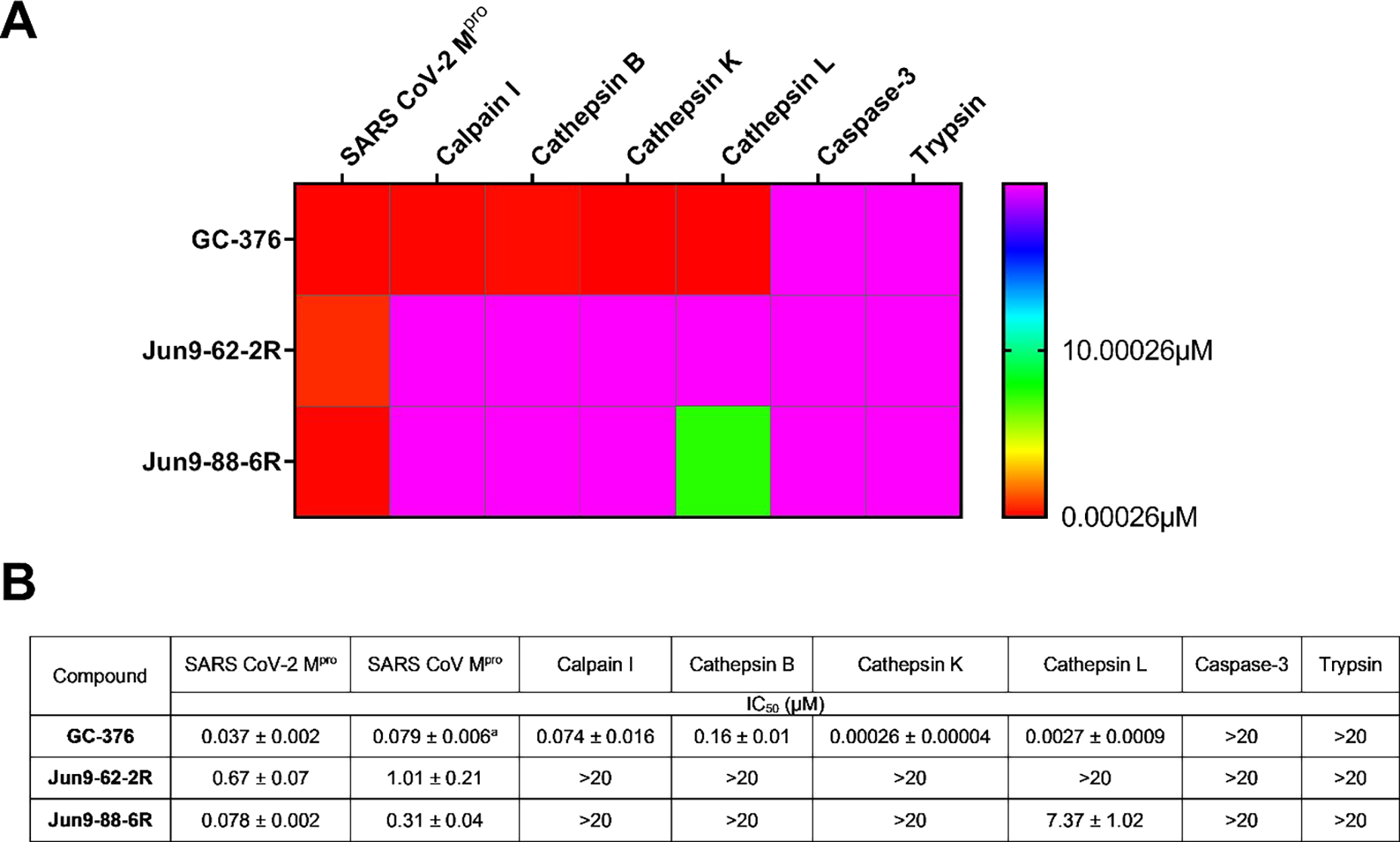

Lack of target specificity is one of the major reasons that many cysteine protease inhibitors failed in the clinical trials. To profile the target specificity of these SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors with a novel reactive warhead, we selected Jun9-62-2R and Jun9-88-6R as representative examples and included the canonical GC-376 with an aldehyde reactive warhead for comparison. The results showed that GC-376 had potent inhibition of the host proteases including calpain I, cathepsin B, cathepsin K, and cathepsin L with IC50 values in the submicromolar and nanomolar range. GC-376 did not inhibit caspase-3 and trypsin (IC50 > 20 μM) (Figure 7). In comparison, both Jun9-62-2R and Jun9-88-6R had a significantly improved target selectivity and did not show potent inhibition against the host calpain 1, cathepsin B, cathepsin K, cathepsin L, caspase-3, and trypsin. Jun9-88-6R had weak inhibition against cathepsin L with an IC50 of 7.37 μM, conferring a 94-fold higher selectivity for inhibiting the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Collectively, the covalent SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors Jun9-62-2R with the dichloroacetamide warhead and Jun9-88-6R with the tribromoacetamide warhead have high target specificity against Mpro over host proteases.

Figure 7.

Target selectivity of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors against host proteases. (A) Heat map of target selectivity. (B) IC50 values of Jun9-62-2R and Jun9-88-6R against host proteases in the FRET-based enzymatic assay. aThe result was from reference20

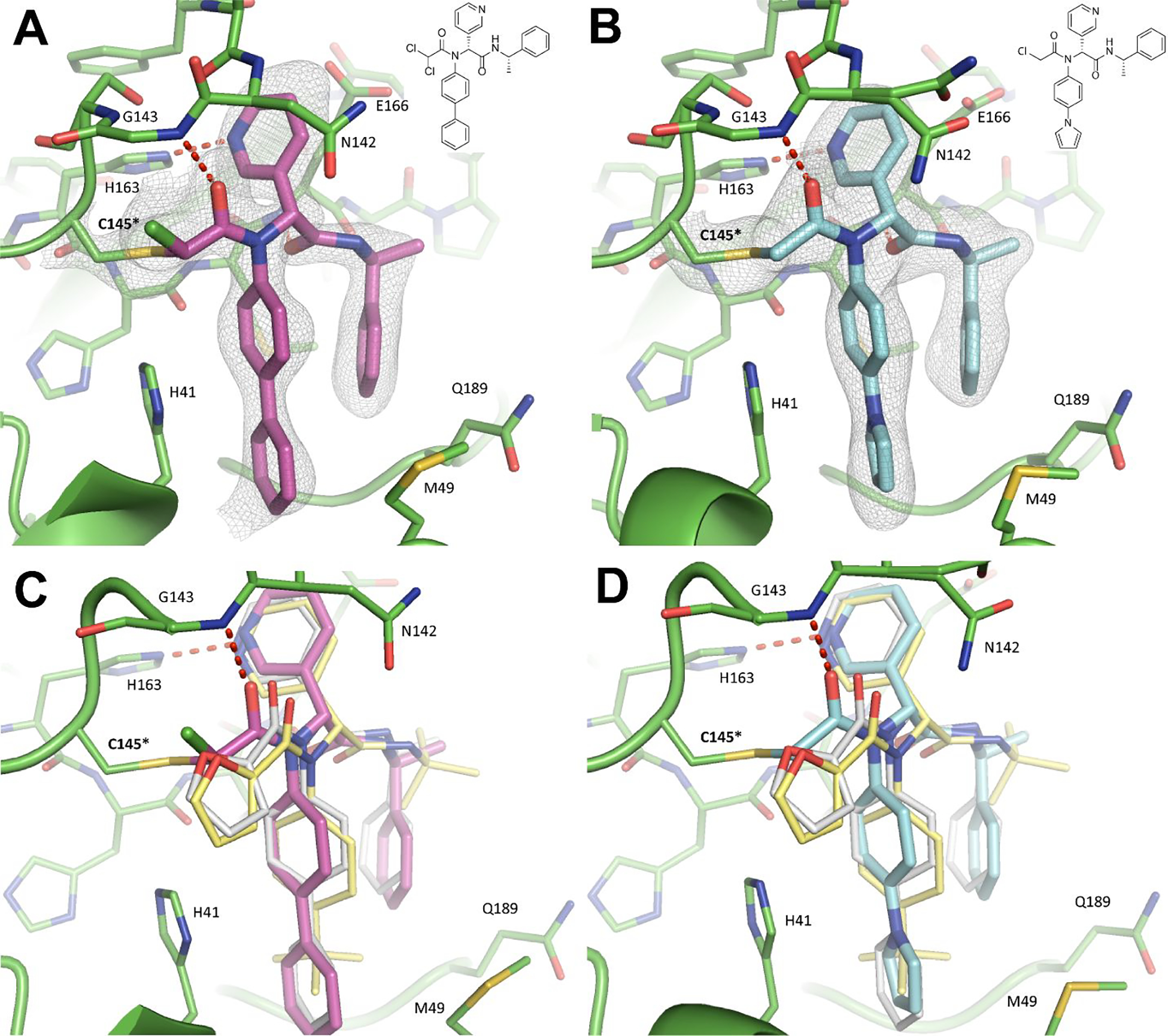

X-ray crystal structures of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in complex with Jun9-62-2R and Jun9-57-3R.

Using X-ray crystallography we solved the complex structures of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with Jun9-57-3R (2.25 Å, PDB ID 7RN0) and Jun9-62-2R (2.30 Å, PDB ID 7RN1) (Figure 8, Table S1). Jun9-57-3R and Jun9-62-2R have nearly identical chemical features to their non-covalent progenitor 23R (Jun8–76-3A) (PDB ID 7KX5). As such, the binding poses are very similar. The pyridyl ring binds to the S1 pocket of Mpro, where it forms a hydrogen bond with His163. This hydrogen bond is critical for coordinating the Gln sidechain of its substrate, a residue it is uniquely selective for. Consequently, a hydrogen bond acceptor at this position confers tremendous potency to Mpro inhibitors. The phenylpyrrole (Jun9-57-3R) or biphenyl (Jun9-62-2R) moieties insert into the hydrophobic S2 pocket where they form nonpolar contacts and stack with the catalytic base, His41. An amide group linking the pyridyl ring to an α-methylbenzene group accepts a hydrogen bond from the mainchain of Glu166. This α-methylbenzene group flips down towards the core of the substrate channel, where it forms additional pi-stacking interactions with the biphenyl or phenylpyrrole moieties. The key distinction between Jun9-62-2R, Jun9-57-3R, and analogues Jun8–76-3A and ML188 is the presence of an electrophilic chloroacetamide warhead, which forms a covalent adduct with the catalytic cysteine Cys145 (Figure 8C–D). The short distance of this covalent bond (1.8 Å) allows the inhibitor to press further into the oxyanion hole, causing the P2 benzene to rotate inwards by ~ 40 °. Likewise, the chloracetamide warhead is forced towards the catalytic core, causing the P1’ chloride of Jun9-57-3R to lie closer to Cys145 (2.8 Å) than the corresponding furyl oxygen of Jun8–76-3A (3.2Å).

Figure 8.

X-ray crystal structures of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in complex with Jun9-62-2R (A) and Jun9-57-3R (B). 2Fo-Fc electron density map, shown in gray, is contoured at 1σ. Structural superimposition of the noncovalent analogues Jun8–76-3A (white, PDB ID 7KX5) and ML188 (yellow, PDB ID 7L0D) with Jun9-62-2R (C) and Jun9-57-3R (D) reveal a different mode of interaction with the catalytic core.

CONCLUSION

The majority of the reported Mpro inhibitors contain the aldehyde reactive warhead, which is known to have non-specific reactivity towards host proteins.16–19 It should be noted that both the Pfizer Mpro inhibitors that are currently in clinical trials do not contain the aldehyde warhead.9–10 As such, we are interested in developing SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors with high target specificity. A highly specific Mpro inhibitor is also needed for target validation as it separates the effect of Mpro inhibition from host protease inhibition such as cathepsin L. It is known that host cathepsin L is important in SARS-CoV-2 replication in Vero E6 cells, which are TMPRSS2-negative, but not in Calu-3 cells, which are TMPRSS2-positive.37 In this study, we report the discovery of dichloroacetamide, dibromoacetamide, 2-bromo-2, 2-dichloroacetamide, 2-chloro-2, 2-dibromoacetamide, and tribromoacetamide as novel cysteine reactive warheads. To the best of our knowledge, these warheads have not been explored in cysteine protease inhibitors. The most promising lead compounds Jun9-62-2R with the dichloroacetamide warhead and Jun9-88-6R with the tribromoacetamide inhibited SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with IC50 values of 0.43 μM and 0.08 μM, respectively. These two compounds also showed potent inhibition against SARS-CoV2 in both Vero E6 and Caco2-hACE2 cells with EC50 values in the single-digit to submicromolar range. Significantly, both Jun9-62-2R and Jun9-88-6R had high target specificity towards Mpro and did not inhibit the host proteases including calpain I, cathepsin B, cathepsin K, cathepsin L, caspase-3, and trypsin. In comparison, GC-376 was not selective and inhibited calpain I, cathepsin B, cathepsin K, and cathepsin L with comparable potency as Mpro. Regarding the translational potential of the di- and trihaloacetamide-containing Mpro inhibitors, the widely used antibiotic chloramphenicol contains the dichloroacetamide, suggesting Jun9-62-2R might be tolerated in vivo. Follow up studies will optimize the in vitro and in vivo pharmacokinetic properties and in vivo antiviral efficacy of these novel compounds in SARS-CoV-2 infection animal models. Other potential strategies of developing selective Mpro inhibitors including allosteric inhibitors38–39 or targeting the more reactive Cys44 at the S2 binding pocket.40–41 Overall, these novel compounds represent valuable chemical probes for target validation and promising drug candidates for translational development as SARS-CoV-2 antivirals.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

J. W. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Grants AI158775, AI147325, and AI157046) and the Arizona Biomedical Research Centre Young Investigator grant (ADHS18-198859). We thank Naoya Kitamura for the preliminary work on the synthesis of some of compounds listed in this paper. The antiviral assay in Calu-3 cells was conducted by Drs. David Schultz and Sara Cherry at the University of Pennsylvania through the NIAID preclinical service under a non-clinical evaluation agreement. Y.H. was supported by the T32 GM008804 training grant. We thank Michael Kemp for assistance with crystallization and X-ray diffraction data collection. SBC-CAT is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. Y.X. was supported by a COVID-19 pilot grant from UTHSCSA and NIH grant AI151638. SARS-Related Coronavirus 2, Isolate USA-WA1/2020 (NR-52281) was deposited by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH.

Footnotes

Competing interests

A patent was filled by Jun Wang which claims the potential use of Jun9-62-2R and related analogs as COVID-19 antiviral drug candidates.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting information

The supporting information is available free of charge at

Additional figures and tables describing the experimental materials, methods, X-ray data set, synthesis and characterization of the Mpro inhibitors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harvey WT; Carabelli AM; Jackson B; Gupta RK; Thomson EC; Harrison EM; Ludden C; Reeve R; Rambaut A; Peacock SJ; Robertson DL; Consortium C-GU, SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19 (7), 409–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox RM; Wolf JD; Plemper RK, Therapeutically administered ribonucleoside analogue MK-4482/EIDD-2801 blocks SARS-CoV-2 transmission in ferrets. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6 (1), 11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morse JS; Lalonde T; Xu S; Liu WR, Learning from the Past: Possible Urgent Prevention and Treatment Options for Severe Acute Respiratory Infections Caused by 2019-nCoV. Chembiochem 2020, 21 (5), 730–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiao J; Li YS; Zeng R; Liu FL; Luo RH; Huang C; Wang YF; Zhang J; Quan B; Shen C; Mao X; Liu X; Sun W; Yang W; Ni X; Wang K; Xu L; Duan ZL; Zou QC; Zhang HL; Qu W; Long YH; Li MH; Yang RC; Liu X; You J; Zhou Y; Yao R; Li WP; Liu JM; Chen P; Liu Y; Lin GF; Yang X; Zou J; Li L; Hu Y; Lu GW; Li WM; Wei YQ; Zheng YT; Lei J; Yang S, SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitors with antiviral activity in a transgenic mouse model. Science 2021, 371 (6536), 1374–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dampalla CS; Zheng J; Perera KD; Wong LR; Meyerholz DK; Nguyen HN; Kashipathy MM; Battaile KP; Lovell S; Kim Y; Perlman S; Groutas WC; Chang KO, Postinfection treatment with a protease inhibitor increases survival of mice with a fatal SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021, 118 (29), e2101555118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caceres CJ; Cardenas-Garcia S; Carnaccini S; Seibert B; Rajao DS; Wang J; Perez DR, Efficacy of GC-376 against SARS-CoV-2 virus infection in the K18 hACE2 transgenic mouse model. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11 (1), 9609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma C; Sacco MD; Hurst B; Townsend JA; Hu Y; Szeto T; Zhang X; Tarbet B; Marty MT; Chen Y; Wang J, Boceprevir GC -376, and calpain inhibitors II, XII inhibit SARS-CoV-2 viral replication by targeting the viral main protease. Cell Res. 2020, 30 (8), 678–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sacco MD; Ma C; Lagarias P; Gao A; Townsend JA; Meng X; Dube P; Zhang X; Hu Y; Kitamura N; Hurst B; Tarbet B; Marty MT; Kolocouris A; Xiang Y; Chen Y; Wang J, Structure and inhibition of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease reveal strategy for developing dual inhibitors against M(pro) and cathepsin L. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6 (50), eabe0751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owen DR; Allerton CMN; Anderson AS; Aschenbrenner L; Avery M; Berritt S; Boras B; Cardin RD; Carlo A; Coffman KJ; Dantonio A; Di L; Eng H; Ferre R; Gajiwala KS; Gibson SA; Greasley SE; Hurst BL; Kadar EP; Kalgutkar AS; Lee JC; Lee J; Liu W; Mason SW; Noell S; Novak JJ; Obach RS; Ogilvie K; Patel NC; Pettersson M; Rai DK; Reese MR; Sammons MF; Sathish JG; Singh RSP; Steppan CM; Stewart AE; Tuttle JB; Updyke L; Verhoest PR; Wei L; Yang Q; Zhu Y An oral SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Science. 2021, eabl4784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boras B; Jones RM; Anson BJ; Arenson D; Aschenbrenner L; Bakowski MA; Beutler N; Binder J; Chen E; Eng H; Hammond J; Hoffman R; Kadar EP; Kania R; Kimoto E; Kirkpatrick MG; Lanyon L; Lendy EK; Lillis JR; Luthra SA; Ma C; Noell S; Obach RS; O’Brien MN; O’Connor R; Ogilvie K; Owen D; Pettersson M; Reese MR; Rogers T; Rossulek MI; Sathish JG; Steppan C; Ticehurst M; Updyke LW; Zhu Y; Wang J; Chatterjee AK; Mesecar AD; Anderson AS; Allerton C, Preclinical characterization of an intravenuous coronavirus 3CL protease inhibitor for the potentiial treatment of COVID-19. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12(1), 6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghosh AK; Brindisi M; Shahabi D; Chapman ME; Mesecar AD, Drug Development and Medicinal Chemistry Efforts toward SARS-Coronavirus and Covid-19 Therapeutics. ChemMedChem 2020, 15 (11), 907–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai W; Zhang B; Jiang XM; Su H; Li J; Zhao Y; Xie X; Jin Z; Peng J; Liu F; Li C; Li Y; Bai F; Wang H; Cheng X; Cen X; Hu S; Yang X; Wang J; Liu X; Xiao G; Jiang H; Rao Z; Zhang LK; Xu Y; Yang H; Liu H, Structure-based design of antiviral drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science 2020, 368 (6497), 1331–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vuong W; Khan MB; Fischer C; Arutyunova E; Lamer T; Shields J; Saffran HA; McKay RT; van Belkum MJ; Joyce MA; Young HS; Tyrrell DL; Vederas JC; Lemieux MJ, Feline coronavirus drug inhibits the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 and blocks virus replication. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rathnayake AD; Zheng J; Kim Y; Perera KD; Mackin S; Meyerholz DK; Kashipathy MM; Battaile KP; Lovell S; Perlman S; Groutas WC; Chang KO, 3C-like protease inhibitors block coronavirus replication in vitro and improve survival in MERS-CoV-infected mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12 (557), eabc5332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang KS; Ma XR; Ma Y; Alugubelli YR; Scott DA; Vatansever EC; Drelich AK; Sankaran B; Geng ZZ; Blankenship LR; Ward HE; Sheng YJ; Hsu JC; Kratch KC; Zhao B; Hayatshahi HS; Liu J; Li P; Fierke CA; Tseng C-TK; Xu S; Liu WR, A Quick Route to Multiple Highly Potent SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors**. ChemMedChem 2021, 16 (6), 942–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma XR; Alugubelli YR; Ma Y; Vantasever EC; Scott DA; Qiao Y; Yu G; Xu S; Liu WR, MPI8 is Potent against SARS-CoV-2 by Inhibiting Dually and Selectively the SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease and the Host Cathepsin L*. ChemMedChem 2021, doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202100456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steuten K; Kim H; Widen JC; Babin BM; Onguka O; Lovell S; Bolgi O; Cerikan B; Neufeldt CJ; Cortese M; Muir RK; Bennett JM; Geiss-Friedlander R; Peters C; Bartenschlager R; Bogyo M, Challenges for Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Proteases as a Therapeutic Strategy for COVID-19. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7 (6), 1457–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia Z; Sacco M; Hu Y; Ma C; Meng X; Zhang F; Szeto T; Xiang Y; Chen Y; Wang J, Rational Design of Hybrid SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors Guided by the Superimposed Cocrystal Structures with the Peptidomimetic Inhibitors GC-376, Telaprevir, and Boceprevir. ACS Pharmcol. Transl. Sci. 2021, 4 (4), 1408–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vandyck K; Abdelnabi R; Gupta K; Jochmans D; Jekle A; Deval J; Misner D; Bardiot D; Foo CS; Liu C; Ren S; Beigelman L; Blatt LM; Boland S; Vangeel L; Dejonghe S; Chaltin P; Marchand A; Serebryany V; Stoycheva A; Chanda S; Symons JA; Raboisson P; Neyts J, ALG-097111, a potent and selective SARS-CoV-2 3-chymotrypsin-like cysteine protease inhibitor exhibits in vivo efficacy in a Syrian Hamster model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 555, 134–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu Y; Ma C; Szeto T; Hurst B; Tarbet B; Wang J, Boceprevir, Calpain Inhibitors II and XII, and GC-376 Have Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Activity against Coronaviruses. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7 (3), 586–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman RL; Kania RS; Brothers MA; Davies JF; Ferre RA; Gajiwala KS; He M; Hogan RJ; Kozminski K; Li LY; Lockner JW; Lou J; Marra MT; Mitchell LJ; Murray BW; Nieman JA; Noell S; Planken SP; Rowe T; Ryan K; Smith GJ; Solowiej JE; Steppan CM; Taggart B, Discovery of Ketone-Based Covalent Inhibitors of Coronavirus 3CL Proteases for the Potential Therapeutic Treatment of COVID-19. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (21), 12725–12747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rathnayake AD; Zheng J; Kim Y; Perera KD; Mackin S; Meyerholz DK; Kashipathy MM; Battaile KP; Lovell S; Perlman S; Groutas WC; Chang K-O, 3C-like protease inhibitors block coronavirus replication in vitro and improve survival in MERS-CoV–infected mice. Sc. Transl. Med. 2020, 12 (557), eabc5332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dai W; Zhang B; Jiang X-M; Su H; Li J; Zhao Y; Xie X; Jin Z; Peng J; Liu F; Li C; Li Y; Bai F; Wang H; Cheng X; Cen X; Hu S; Yang X; Wang J; Liu X; Xiao G; Jiang H; Rao Z; Zhang L-K; Xu Y; Yang H; Liu H, Structure-based design of antiviral drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science 2020, 368 (6497), 1331–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitamura N; Sacco MD; Ma C; Hu Y; Townsend JA; Meng X; Zhang F; Zhang X; Ba M; Szeto T; Kukuljac A; Marty MT; Schultz D; Cherry S; Xiang Y; Chen Y; Wang J, Expedited Approach toward the Rational Design of Noncovalent SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2021, doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs J; Grum-Tokars V; Zhou Y; Turlington M; Saldanha SA; Chase P; Eggler A; Dawson ES; Baez-Santos YM; Tomar S; Mielech AM; Baker SC; Lindsley CW; Hodder P; Mesecar A; Stauffer SR, Discovery, synthesis, and structure-based optimization of a series of N-(tert-butyl)-2-(N-arylamido)-2-(pyridin-3-yl) acetamides (ML188) as potent noncovalent small molecule inhibitors of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) 3CL protease. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56 (2), 534–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdeldayem A; Raouf YS; Constantinescu SN; Moriggl R; Gunning PT, Advances in covalent kinase inhibitors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49 (9), 2617–2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siklos M; BenAissa M; Thatcher GR, Cysteine proteases as therapeutic targets: does selectivity matter? A systematic review of calpain and cathepsin inhibitors. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2015, 5 (6), 506–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cianni L; Feldmann CW; Gilberg E; Gutschow M; Juliano L; Leitao A; Bajorath J; Montanari CA, Can Cysteine Protease Cross-Class Inhibitors Achieve Selectivity? J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62 (23), 10497–10525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoch DG; Abegg D; Adibekian A, Cysteine-reactive probes and their use in chemical proteomics. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54 (36), 4501–4512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le GT; Abbenante G; Madala PK; Hoang HN; Fairlie DP, Organic Azide Inhibitors of Cysteine Proteases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128 (38), 12396–12397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang P-Y; Wu H; Lee MY; Xu A; Srinivasan R; Yao SQ, Solid-Phase Synthesis of Azidomethylene Inhibitors Targeting Cysteine Proteases. Org. Lett. 2008, 10 (10), 1881–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thorarensen A; Balbo P; Banker ME; Czerwinski RM; Kuhn M; Maurer TS; Telliez J-B; Vincent F; Wittwer AJ, The advantages of describing covalent inhibitor in vitro potencies by IC50 at a fixed time point. IC50 determination of covalent inhibitors provides meaningful data to medicinal chemistry for SAR optimization. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 29, 115865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drayman N; DeMarco JK; Jones KA; Azizi S-A; Froggatt HM; Tan K; Maltseva NI; Chen S; Nicolaescu V; Dvorkin S; Furlong K; Kathayat RS; Firpo MR; Mastrodomenico V; Bruce EA; Schmidt MM; Jedrzejczak R; Muñoz-Alía MÁ; Schuster B; Nair V; Han K.-y.; O’Brie A.; Tomatsidou A; Meyer B; Vignuzzi M; Missiakas D; Botten JW; Brooke CB; Lee H; Baker SC; Mounce BC; Heaton NS; Severson WE; Palmer KE; Dickinson BC; Joachimiak A; Randall G; Tay S, Masitinib is a broad coronavirus 3CL inhibitor that blocks replication of SARS-CoV-2. Science 2021, 373 (6557), 931–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoffmann M; Kleine-Weber H; Schroeder S; Kruger N; Herrler T; Erichsen S; Schiergens TS; Herrler G; Wu NH; Nitsche A; Muller MA; Drosten C; Pohlmann S, SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181 (2), 271–280 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bertram S; Glowacka I; Blazejewska P; Soilleux E; Allen P; Danisch S; Steffen I; Choi SY; Park Y; Schneider H; Schughart K; Pohlmann S, TMPRSS2 and TMPRSS4 facilitate trypsin-independent spread of influenza virus in Caco-2 cells. J. Virol. 2010, 84 (19), 10016–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanifer ML; Kee C; Cortese M; Zumaran CM; Triana S; Mukenhirn M; Kraeusslich HG; Alexandrov T; Bartenschlager R; Boulant S, Critical Role of Type III Interferon in Controlling SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Human Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Cell Rep. 2020, 32 (1), 107863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shang J; Wan Y; Luo C; Ye G; Geng Q; Auerbach A; Li F, Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117 (21), 11727–11734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gunther S; Reinke PYA; Fernandez-Garcia Y; Lieske J; Lane TJ; Ginn HM; Koua FHM; Ehrt C; Ewert W; Oberthuer D; Yefanov O; Meier S; Lorenzen K; Krichel B; Kopicki JD; Gelisio L; Brehm W; Dunkel I; Seychell B; Gieseler H; Norton-Baker B; Escudero-Perez B; Domaracky M; Saouane S; Tolstikova A; White TA; Hanle A; Groessler M; Fleckenstein H; Trost F; Galchenkova M; Gevorkov Y; Li C; Awel S; Peck A; Barthelmess M; Schlunzen F; Lourdu Xavier P; Werner N; Andaleeb H; Ullah N; Falke S; Srinivasan V; Franca BA; Schwinzer M; Brognaro H; Rogers C; Melo D; Zaitseva-Doyle JJ; Knoska J; Pena-Murillo GE; Mashhour AR; Hennicke V; Fischer P; Hakanpaa J; Meyer J; Gribbon P; Ellinger B; Kuzikov M; Wolf M; Beccari AR; Bourenkov G; von Stetten D; Pompidor G; Bento I; Panneerselvam S; Karpics I; Schneider TR; Garcia-Alai MM; Niebling S; Gunther C; Schmidt C; Schubert R; Han H; Boger J; Monteiro DCF; Zhang L; Sun X; Pletzer-Zelgert J; Wollenhaupt J; Feiler CG; Weiss MS; Schulz EC; Mehrabi P; Karnicar K; Usenik A; Loboda J; Tidow H; Chari A; Hilgenfeld R; Uetrecht C; Cox R; Zaliani A; Beck T; Rarey M; Gunther S; Turk D; Hinrichs W; Chapman HN; Pearson AR; Betzel C; Meents A, X-ray screening identifies active site and allosteric inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science 2021, 372 (6542), 642–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Douangamath A; Fearon D; Gehrtz P; Krojer T; Lukacik P; Owen CD; Resnick E; Strain-Damerell C; Aimon A; Ábrányi-Balogh P; Brandão-Neto J; Carbery A; Davison G; Dias A; Downes TD; Dunnett L; Fairhead M; Firth JD; Jones SP; Keeley A; Keserü GM; Klein HF; Martin MP; Noble MEM; O’Brien P; Powell A; Reddi RN; Skyner R; Snee M; Waring MJ; Wild C; London N; von Delft F; Walsh MA, Crystallographic and electrophilic fragment screening of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang C; Wei P; Fan K; Liu Y; Lai L, 3C-like Proteinase from SARS Coronavirus Catalyzes Substrate Hydrolysis by a General Base Mechanism. Biochemistry 2004, 43 (15), 4568–4574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verma N; Henderson JA; Shen J, Proton-Coupled Conformational Activation of SARS Coronavirus Main Proteases and Opportunity for Designing Small-Molecule Broad-Spectrum Targeted Covalent Inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (52), 21883–21890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.