To the Editor:

It is well known that myeloid malignancies can evolve from antecedent hematologic disorders, most commonly acute myeloid leukemia (AML) evolving from myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). Although aplastic anemia (AA) and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) are not intrinsically malignant conditions, they, too, can evolve to myeloid malignancies, albeit at a lower frequency than other bone marrow disorders, like MDS. While AA has been shown to be associated with somatic mutations prior to evolution to, e.g., MDS, PNH has not [1, 2]. We revisited the issue of malignant transformation of PNH to myeloid conditions in the setting of the current availability of somatic mutational testing (Table 1). Previous reports of PNH transformation contain grouped data and lack many details including time to malignant progression and associated molecular characterization [3–6] (Table S1). Our series of PNH cases evolving to MDS/AML was derived from 243 adult patients evaluated for hemolytic PNH including primary (pPNH: patients without antecedent AA) and secondary (sPNH: patients evolving from AA with PNH clone >20%) (n = 83), AA, and AA/PNH (n = 160; Table S2). Among those with hemolytic PNH, 7 patients progressed to AML (n = 1), MDS (n = 5), or myelofibrosis (n = 1) (Table 1). These cases had a median PNH clone size of 71% (range, 29–99) and carried various somatic mutations (ASXL1, BCOR, NPM1, TET2, U2AF1, WT1). The incidence rate of myeloid disorders in all cohorts was 3% (7/243) ranging from 4% to 10% in a meta-analysis (Table S1). Time to MDS/AML diagnosis was <1–22 years in our cohort while ranging from 0 to 3.4 years in one study [3] and had a cumulative incidence of 2 years (1.2% [0.9]) for MDS and (4.0% [1.4]) for AML in another [4] (Table S1). These results help to approximate the risk of clonal evolution in PNH.

Table 1.

Characteristics of hemolytic PNH patients who progressed to myeloid disorders

| Case | Gender | Agea (years) | Antecedent diagnosis | Time to progression (years) | Diagnosis at progression | Conventional cytogenetics | Somatic mutations | PNHd clone size (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 80 | pPNHb | 5 | AML/MDS | Normal | ASXL1, U2AF1 | 94.7 |

| 2 | M | 69 | pPNH | <1 | MF | Normal | U2AF1 | 71.3 |

| 3 | M | 63 | pPNH | 22 | MDS | +8 | None | 99.6 |

| 4 | M | 23 | sPNHc | 4 | MDS | −7 | TET2 | 72.9 |

| 5 | M | 48 | sPNH | 4 | MDS | del(13q) | BCOR | 70.6 |

| 6 | F | 44 | sPNH | 4 | MDS | Normal | BCOR, NPM1, WT1 | 46.9 |

| 7 | F | 24 | sPNH | <1 | MDS | del(13q) | None | 29.3 |

pPNH primary hemolytic paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, sPNH secondary hemolytic paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, MDS myelodysplastic syndrome, AML acute myeloid leukemia, MF myelofibrosis, M male, F female

At the time of first sampling

Primary PNH indicates patients without antecedent AA

Secondary PNH indicates patients evolving from AA with PNH clone >20%

PNH clone size on white blood cells

While PNH has been classically considered a molecularly monogenic disease due to somatic PIGA mutations (PIGAMT) (most of the cases) or microdeletions of the PIGA locus (Xp22.2; a few cases) [7], our recent sequencing studies of PNH and non-PNH cells have identified, besides PIGAMT, accessory somatic hits—a finding consistent with a more complex clonal architecture present in some PNH patients. While early studies by our group examined the spectrum of somatic lesions of PNH patients, the current study aims to explore the potentiality of clonal evolution due to somatic hits [8–10].

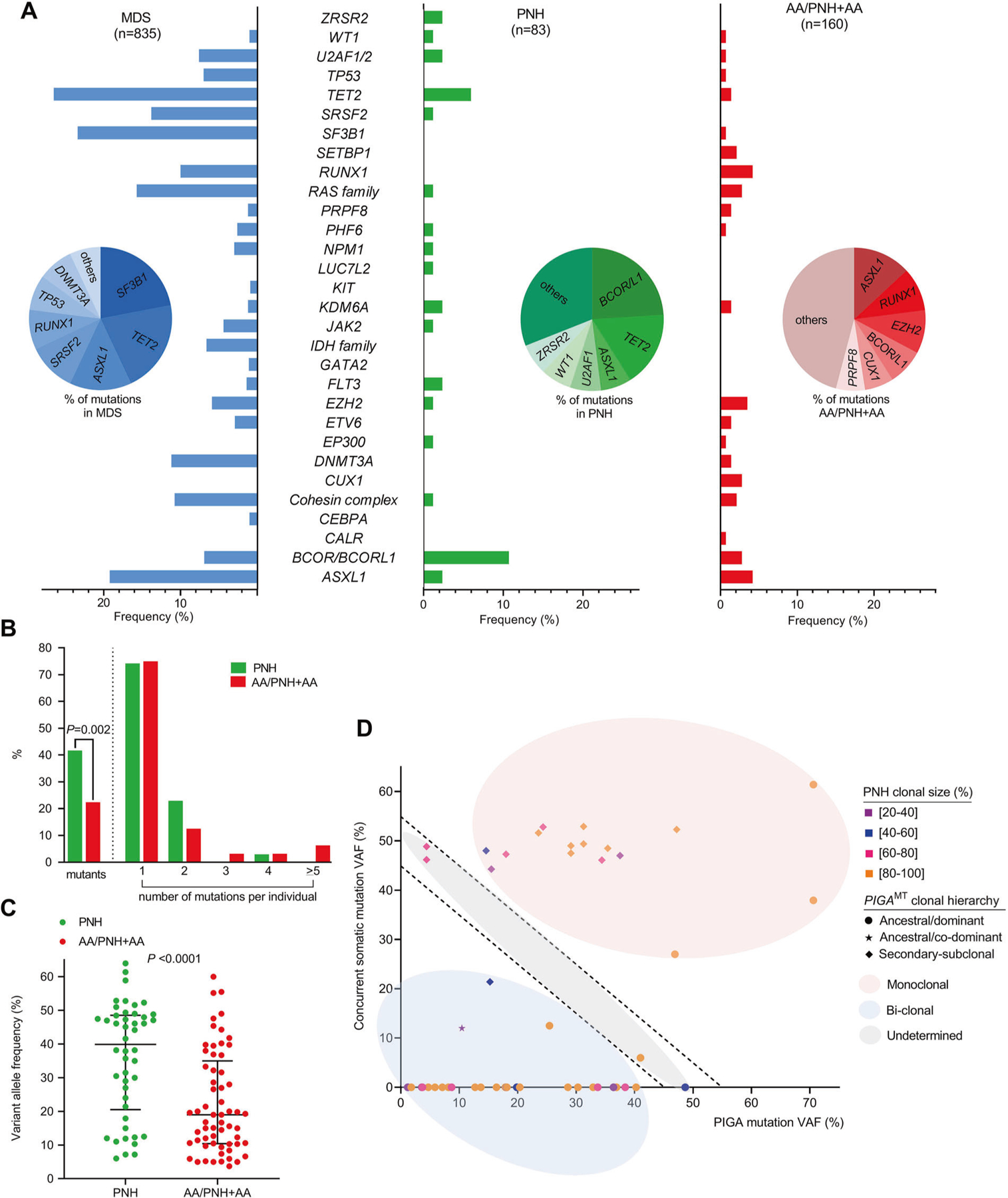

Unlike previously described cases (Table S1), our report fully exploited modern molecular genotyping. Mutations identified in our series suggest a possible cooperation with PIGAMT in the clonal expansion of PNH hematopoietic stem cells. Indeed, 4 cases had abnormal karyotype (+8, −7, del13q) and 5 cases carried mutations affecting genes typically mutated in MDS/AML (ASXL1, U2AF1). Of note, BCOR and U2AF1 mutations were present in two patients each. Detection of mutations in PNH/MDS patients prompted us to perform a subsequent analysis of the molecular spectrum of other PNH patients and of those with AA/PNH and AA to determine whether clonal hits and their mutational frequency differ between these subgroups and have prognostic significance. Moreover, we sought to identify clues as to whether the presence of AA or that of ancestral PIGAMT contributes to the risk of malignant evolution in PNH evidenced through predilection of specific mutations. Hence, we subdivided PNH patients into pPNH and sPNH and studied clinical and molecular characteristics in comparison to those found in MDS patients (Table S2). We combined results from next-generation sequencing performed using various library preparation systems (TruSeq, TruSight, Nextera) [8, 10, 11] to target genes commonly mutated in MDS/AML (Table S3). Somatic nature of identified mutations was established by using described pipelines (Fig. S1). Mutations were divided according to the Cancer Gene Census: Tier 1 (variants with documented activity relevant to cancer); Tier 2 (variants with strong indications of activities in cancer but with less documentation; Table S4). In total, 107 somatic mutations (besides PIGAMT) were detected. When we analyzed the mutational profile of PNH vs. AA/PNH+AA and MDS, we found that PNH showed a significantly higher proportion of mutant individuals as compared to AA/PNH+AA (42% vs. 22% of cases with ≥1 mutation; P = 0.002; Fig. 1a, b). The median variant allele frequency (VAF) percentage of all mutations was significantly higher in PNH vs. AA/PNH+AA (40% vs. 19%; P < 0.0001; Fig. 1c). Mutations involving FLT3 (n = 2), JAK2 (n = 1), LUC7L2 (n = 1), NPM1 (n = 1), SRSF2 (n = 1), and ZRSR2 (n = 2) were exclusively found in PNH with some of these genes (FLT3, NPM1) possibly representing an early onset of leukemia evolution. BCOR/BCORL1 were more mutated in PNH as compared to AA/PNH+AA patients (11% vs. 3%; P = 0.01). A similar trend was also observed for TET2 and U2AF1 mutations in PNH vs. AA/PNH+AA groups (6% vs. 1%; P = 0.1; 2% vs. 0.7%; P = 0.5). This pattern of mutations had a strong similarity with that of MDS (Fig. 1a). Conversely, CALR (n = 1), CUX1 (n = 4), DNMT3A (n = 2), ETV6 (n = 2), PRPF8 (n = 2), RUNX1 (4%, n = 6), SETBP1 (n = 3), SF3B1 (n = 1), and TP53 (n = 1) mutations were only seen in both AA/PNH+AA. In AA, somatic mutations in “myeloid” genes have been reported in about 30% of patients, with mutations in age-related genes (DNMT3A, ASXL1) correlating with worse prognosis [8, 12–15].

Fig. 1.

Mutational spectrum and clonal hierarchy of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH). a Bar charts summarize the frequencies of mutations in the three groups: myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS; n = 835), hemolytic PNH (PNH; n = 83), and aplastic anemia (AA) and AA/PNH (AA+AA/PNH; n = 160). BCOR/BCORL1 were the most common mutations in PNH while ASXL1, EZH2, and RUNX1 mutations were enriched in AA+AA/PNH. Pie charts indicate the percentage of mutations per group. b Bar graph showing the percentage of mutant patients (≥1 mutation per group) and the percentage of individuals per number of mutations carried in each group (green, PNH; red, AA+AA/PNH). c Scatter plot summarizing the variant allele frequency (VAF) of mutations in patients with PNH and AA+AA/PNH indicates the median with interquartile range. The P value was calculated by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. d Scatter plot representing the clonal hierarchy was generated by illustrating the VAF of PIGA mutations and concurrent somatic mutations. It also categorizes the mutations as monoclonal (hits present in the same clone; VAF sum >55), bi-clonal (hits present in different clones; VAF sum <45%), and undetermined (can be either monoclonal or bi-clonal; VAF sum lying between 45% and 55%). The PNH clonal size per patient is also displayed

These findings suggest that the molecular architecture of patients with PNH is likely more similar to that of MDS rather than of AA, pointing out diverse mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. Therefore, we then focused on the nature of clonal evolution in PNH. Our group previously described the presence of an initial cellular pool with multiple PIGAMT from which a single clone gradually competes for the dominance and emerges above all others [10]. We now hypothesize that the emergent PNH clone acquires an intrinsic clonal advantage supported by additional mutations. Therefore, we analyzed the clonal hierarchy of mutations first by VAF (adjusted for X-chromosomal loci in males) and then inferred clonal succession to the mutations as ancestral (dominant/co-dominant) vs. secondary (sub-clonal). PIGAMT were dominant in 70% of the cases, co-dominant in 2%, and secondary in 28% suggesting the presence of additional mutations representing collaborating events. Indeed, comparison of VAFs and PNH clonal size showed that 70% of the hits were present in the same clone (VAFSUM > 55), 17% were undetermined (possibly bi-clonal; VAFSUM between 45 and 55), while 13% were more likely a result of clonal chimerism (hits present in different clones; VAFSUM < 45). These observations suggest that most PNH cases carried additional mutations in the same clone and these mutations were secondary hits, with PIGAMT being the founder lesion (Fig. 1d). Even when mutations in myeloid genes were ancestral, the PNH phenotype preceded the myeloid clonal phenotype given the high percentage of PNH cells (Fig. 1d). This observation supports the simple nature of PNH as a monogenic disease with pleomorphic clinical manifestations reflecting the impairment of PIGA rather than the one of myeloid genes. This disease picture diverges from the one of MDS and/or AML where complexity of somatic mutations produces a heterogeneity of cellular and morphologic phenotypes. In such a cellular context, the presence of cooperating mutations increases the complexity of PIGA clonal architecture, conferring a growth advantage and in rare circumstances changes the cell’s fate favoring clonal progression. Although clonal evolution of hemolytic PNH to MDS/AML is rare, it is much more frequent than in comparable general populations and clonal evolution is accompanied by mutations in typical myeloid genes (BCOR, NPM1, TET2, U2AF1) although it is not triggered by a unique driver gene remaining a private feature of individual patients. Of note, reverse screening of MDS for the presence of PNH clones showed exceeding low detection rates when stringent criteria for MDS diagnosis was applied, indicating that PIGAMT are uncommon secondary events in MDS.

In summary, this study highlights the importance of molecular screening in PNH and finds that early detection of myeloid clonal events (although with a lower mutational burden compared to MDS/AML) might alert for molecular surveillance in PNH patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Edward P. Evans Foundation for the grants R01HL118281, R01HL123904, R01HL132071, R35HL135795 (to J.P.M), AA&MDSIF, VeloSano Pilot Award, and Vera and Joseph Dresner Foundation–MDS (to V.V.).

Footnotes

Supplementary information The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-019-0555-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Young NS, Maciejewski JP, Sloand E, Chen G, Zeng W, Risitano A, et al. The relationship of aplastic anemia and PNH. Int J Hematol 2002;76:168–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris JW, Koscick R, Lazarus HM, Eshleman JR, Medof ME. Leukemia arising out of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Leuk Lymphoma 1999;32:401–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham DL, Gastineau DA. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria as a marker for clonal myelopathy. Am J Med 1992;93:671–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Socie G, Mary JY, de Gramont A, Rio B, Leporrier M, Rose C, et al. Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria: long-term follow-up and prognostic factors. French Society of Haematology. Lancet 1996;348:573–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishimura J, Kanakura Y, Ware RE, Shichishima T, Nakakuma H, Ninomiya H, et al. Clinical course and flow cytometric analysis of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria in the United States and Japan. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004;83:193–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loschi M, Porcher R, Barraco F, Terriou L, Mohty M, de Guibert S, et al. Impact of eculizumab treatment on paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: a treatment versus no-treatment study. Am J Hematol 2016;91:366–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Keefe CL, Sugimori C, Afable M, Clemente M, Shain K, Araten DJ, et al. Deletions of Xp22.2 including PIG-A locus lead to paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Leukemia 2011; 25:379–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Negoro E, Nagata Y, Clemente MJ, Hosono N, Shen W, Nazha A, et al. Origins of myelodysplastic syndromes after aplastic anemia. Blood 2017;130:1953–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen W, Clemente MJ, Hosono N, Yoshida K, Przychodzen B, Yoshizato T, et al. Deep sequencing reveals stepwise mutation acquisition in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. J Clin Invest 2014;124:4529–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemente MJ, Przychodzen B, Hirsch CM, Nagata Y, Bat T, Wlodarski MW, et al. Clonal PIGA mosaicism and dynamics in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Leukemia 2018; 32:2507–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirsch CM, Nazha A, Kneen K, Abazeed ME, Meggendorfer M, Przychodzen BP, et al. Consequences of mutant TET2 on clonality and subclonal hierarchy. Leukemia 2018;32:1751–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshizato T, Dumitriu B, Hosokawa K, Makishima H, Yoshida K, Townsley D, et al. Somatic mutations and clonal hematopoiesis in aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med 2015;373:35–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silver AJ, Jaiswal S. Clonal hematopoiesis: pre-cancer PLUS. Adv Cancer Res 2019;141:85–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mufti GJ, Marsh JCW. Somatic mutations in aplastic anemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2018;32:595–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luzzatto L, Risitano AM. Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of acquired aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol 2018;182:758–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.