Abstract

Objective:

To assess effects of emotional eating and stress on weight change among Black women in a culturally tailored weight control program.

Methods:

SisterTalk, a cable-TV delivered weight control randomized trial, included 331 Black women (ages 18–75 years; BMI ≥ 25) in Boston, MA. BMI and waist circumference (WC) were assessed at baseline and 3, 8, and 12-months post-randomization. Frequency of, “eating when depressed or sad,” (EWD) and, “eating to manage stress,” (ETMS) (i.e., “emotional eating”) and perceived stress were also assessed. Lagged analyses of data for intervention participants (n=258) assessed associations of BMI and WC outcomes at each follow-up visit with EWD and ETMS frequency and stress measured at the most recent prior visit.

Results:

At 3-months (immediately post intervention), BMI decreased for women in all EWD and ETMS categories, but increased at later follow up for women reporting EWD and ETMS always/often. Eight-month EWD and ETMS predicted 12-month BMI change (both p<0.05). Higher perceived stress was associated with higher EWD and ETMS, however, stress was not associated with lagged BMI or WC at any time.

Conclusions:

Addressing emotional eating and related triggers may improve weight maintenance in interventions with Black women.

Keywords: Obesity, emotional eating, weight maintenance

INTRODUCTION:

Stress may play an important role in racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in weight status and may be particularly important in examining determinants of effective weight management in Black women. The connection of stress with generalized and abdominal obesity is well established and has been extended to considerations of racial/ethnic disparities in obesity.1 As much as 20% of the differences in obesity between racial/ethnic minority groups can be explained by stress exposures.2 As compared to their white counterparts, Black women report a greater exposure to certain types of stressors (e.g. discrimination, low socioeconomic status) and report higher levels of stress overall.3 One mechanism for this association between stress and weight status could be the impact of stress on food consumption. A direct connection between stress and unhealthy eating was made for Black Americans, including both emotional eating and low quality food intake, in the Americans’ Changing Lives Survey.4 Negative emotions and stress have been found to contribute to emotional eating.5 The environmental context within which many Black Americans live may contribute to this pathway. For example, among low-income Black women, food insecurity and food deserts were found to have an adverse effect on emotional eating, emotional coping, coping strategies, and depressive symptoms.6 Also, among a sample of predominantly Black women in South Carolina, women in food insecure households had higher emotional eating and depressive symptoms compared with women in food secure households.7 This pattern was also found in another South Carolina study of mostly Black women, which found that depressive symptoms were associated in part with emotional eating.8 Increased access to high calorie and high fat foods and less availability of healthy foods at the neighborhood-level may increase the likelihood that deleterious effects of stress contribute to disparities in obesity.9 Thus, stress experienced by Black women may be expressed as coping through emotional eating, and combined with unhealthy food environments, may be partly responsible for unhealthy dietary behaviors and increased risk of obesity.

Given these associations, factors related to stress and emotional eating might be important components to include in consideration of weight loss and maintenance for Black women. The focus on Black women is especially important due to the markedly high risk of obesity10 and related diseases11 among this population. This focus is also well founded because of the consistent findings that weight control interventions have been less successful for Black women, with Black women with overweight losing less weight compared to white men or women or Black men with overweight.12

The purpose of this paper is to examine relationships between stress and emotional eating behaviors, on changes in BMI and WC in a sample of Black women participating in the SisterTalk weight control study. In this paper we focus our attention on how emotional eating and stress are associated with changes in BMI and WC over time. We prioritize these factors as they may be amenable to change through targeted interventions.

METHODS:

The SisterTalk project was a randomized controlled trial of a cable television-delivered intervention to help Black women “eat better and move more,” control their weight, and to a small extent, to manage stress. The study has been described in greater detail elsewhere 13 and demonstrated that women who received the intervention were more likely to control their weight, be more physically active in the short term, and eat less dietary fat sustained over the long term compared with wait-list control participants.13,14 Participants were 331 self-identified Black or African American women ages 18 to 75 years of age, with a mean BMI of 36 kg/m2, recruited from clinical and community sites in and around Boston, MA. An extensive formative research phase explored diet and physical activity behaviors, barriers and facilitators to change, and the social and cultural influences of food choices and physical activity patterns to inform intervention development.14 Overeating, emotional eating, and snacking behaviors were commonly identified in focus groups as problematic.

Prospective participants completed a baseline telephone survey and attended an in-person screening visit for collection of additional questionnaire data and physical measurements. (Three women with measured BMI<25 were excluded from these analyses.) Eligible participants (n=363) were assigned to one of five experimental groups: a wait list comparison group and four experimental groups that received the cable TV show with and without different enhancements, (social support through lay educator phone calls, and/or live interaction with the show presenters through call-ins).13,14 The intervention was delivered weekly for 12 weeks and then monthly (through mailed videos) for 4 months. In the main analysis,13 the four intervention groups were combined into one treatment group receiving the cable TV program compared to the wait listed comparison group because the intervention components of social support calls and live interaction during the show were not found to significantly influence outcomes beyond the effects of the TV program. At 3, 8 and 12 month follow-ups, 63, 71 and 68%, respectively of the randomized participants were measured. There were no differences in baseline BMI between those who were retained compared with those who were not. For the current analysis, participants of the four intervention groups were included (n=258).

Measures

Surveys measured demographics, stress, and emotional eating behaviors.13,14 Stress was assessed with a single, original, global question: “On a scale of 1–10, how stressful is your life?” This measure was later compared to the Perceived Stress Scale15 in a subsequent study of Black women enrolled in a weight loss trial (rho=.41 p= .0001, unpublished). Based on the distribution of frequencies, stress categories were created for low (responses 1–4), medium (5–7) and high (8–10). Two emotional eating questions assessed how often participants “eat when feeling depressed or sad,” (EWD) or “eat to manage stress,” (ETMS) with response options given as “almost always”, “often”, “sometimes”, “rarely” and “never.” Due to small sample sizes for some responses, categories for analysis were collapsed to be Almost Always/Often, Sometimes, and Rarely/Never. These questions match very well with emotional eating questions from other measures, such as the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire,16 but were not validated in this study.

Anthropometric measurements taken during the in-person meeting included height (by stadiometer), weight (by upright Tanita scale), from which BMI was calculated (kg/m2) and WC (using non-elastic tape, at the level of the umbilicus17). Changes in BMI and WC were calculated as the differences between baseline measurements and each follow-up measure.

Statistical Analyses

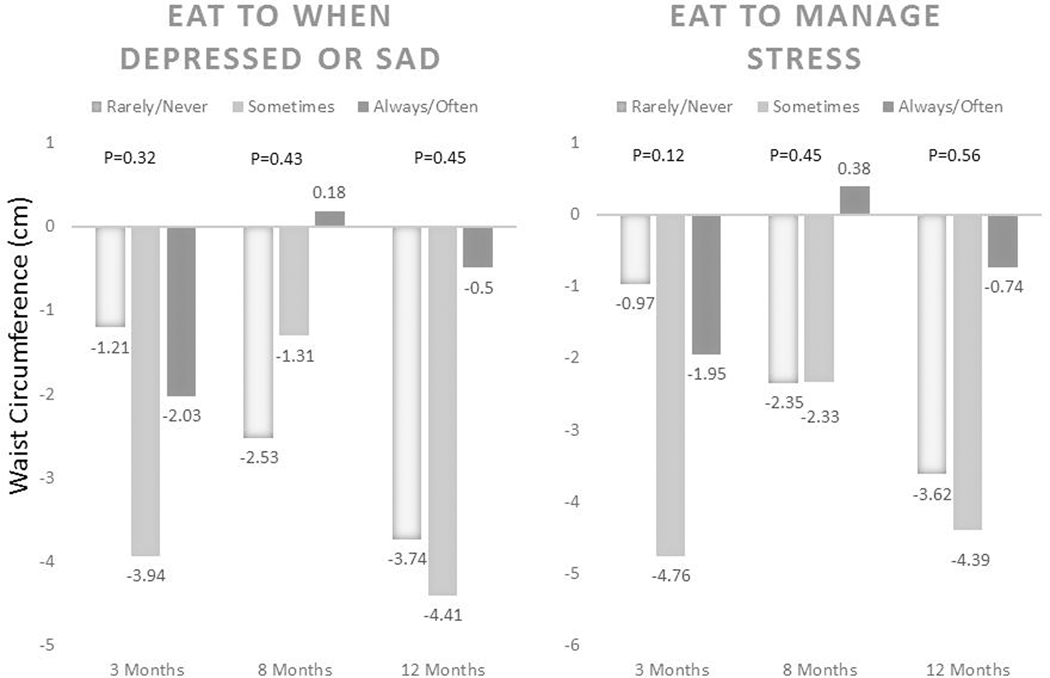

Data were collected in Datstat version 4.7 and analyzed in SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC). Frequencies of emotional eating (EWD and ETMS) were compared with demographic and weight status variables at baseline using a chi-square test of independence (Table 1). Changes in BMI were calculated from baseline to each of the three follow-up periods (3, 8 and 12 months). To best represent the influences of emotional eating factors on weight change prospectively, reported EWD, ETMS, and stress were lagged one time-period in BMI and WC in the models. In these models EWD, ETMS and stress from the preceding time period were entered into a model with BMI or WC from a given time point (e.g. baseline EWD and ETMS were entered into models with 3 month BMI and WC). Mean changes in BMI and WC were compared with lagged response categories of EWD and ETMS using analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Figures 1 & 2), with adjustment for employment status.

Table 1.

Baseline Differences for EWD and ETMS by Demographic Subgroups NEW

| All n=258 | EWD n=256 | ETMS n=254 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Rarely/Never | Sometimes | Always/Often | Rarely/Never | Sometimes | Always/Often | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| 114 (34.8) | 94 (28.7) | 120 (36.6) | 161 (49.4) | 79 (24.2) | 86 (26.4) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | p-value | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | p-value | |

| Age (mean/SD) | 44 (0.68) | 46 (1.16) | 43 (1.25) | 44 (1.12) | 0.12 | 44 (0.98) | 45 (1.37) | 45 (1.33) | 0.80 |

| BMI (mean/SD) | 36 (0.44) | 34 (0.74) | 36 (0.81) | 37 (0.73) | 0.0145 | 35 (0.63) | 36 (0.89) | 38 (0.86) | 0.03 |

| WC(mean/SD) | 102 (1.01) | 98 (1.69) | 105 (1.84) | 105 (1.65) | 0.0028 | 99 (1.44) | 105 (2.02) | 106 (1.96) | 0.02 |

| Education | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p-value | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p-value |

| To 11th grade | 16 (6) | 6 (38) | 5 (31) | 5 (31) | 0.18 | 7 (47) | 5 (33) | 3 (20) | 0.32 |

| High school or GED | 34 (13) | 12 (35) | 10 (29) | 12 (35) | 20 (59) | 8 (24) | 6 (18) | ||

| Some college/tech | 95 (37) | 27 (29) | 44 (26) | 33 (46) | 43 (46) | 19 (20) | 31 (33) | ||

| College graduate | 79 (31) | 31 (40) | 29 (37) | 18 (23) | 41 (52) | 23 (29) | 15 (19) | ||

| Graduate school | 34 (13) | 12 (35) | 7 (21) | 15 (44) | 13 (39) | 8 (24) | 12 (36) | ||

| Income | |||||||||

| <19,999 | 50 (21) | 16(33) | 13(27) | 20(41) | 0.70 | 25 (50) | 10 (20) | 15 (30) | 0.12 |

| 20–39,999 | 104 (44) | 34(33) | 36(35) | 34(33) | 58 (56) | 21 (20) | 24 (23) | ||

| 40–59,999 | 42 (18) | 15(36) | 15(36) | 12(29) | 17 (43) | 16 (40) | 7 (18) | ||

| >60,000 | 39 (17) | 13(33) | 9(23) | 17(44) | 15 (38) | 11 (28) | 13 (33) | ||

| Household Includes | |||||||||

| Children | 54 (21) | 14(26) | 18 (33) | 22(41) | 0.47 | 27 (51) | 12 (23) | 14 (26) | 0.96 |

| Other adults | 58 (22) | 17 (30) | 18 (32) | 22 (39) | 26 (46) | 13 (23) | 18 (32) | ||

| Adults and children | 97 (38) | 35 (36) | 29 (30) | 32 (33) | 46 (48) | 26 (27) | 23 (24) | ||

| Live alone | 49 (19) | 22 (45) | 10 (20) | 17 (35) | 25 (51) | 12 (24) | 12 (24) | ||

| Employment status | |||||||||

| Full-time | 196 (76) | 68 (35) | 63 (32) | 65 (33) | 0.18 | 94 (49) | 54 (28) | 45 (23) | 0.07 |

| Part-time | 26 (10) | 8 (33) | 6 (25) | 10 (42) | 14 (56) | 3 (12) | 8 (32) | ||

| Unemployed > 1year | 18 (7) | 5 (28) | 2 (11) | 11 (61) | 7 (39) | 1 (3) | 10 (56) | ||

| Unemployed <1 year | 14 (5) | 7 (50) | 3 (21) | 4 (29) | 8 (57) | 3 (21) | 3 (21) | ||

| Homemaker | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | ||

| Stress * | |||||||||

| Low | 65 (25) | 28 (43) | 23 (35) | 14 (22) | .0006 | 43 (67) | 14 (22) | 7 (11) | .0009 |

| Mid | 91 (36) | 39 (43) | 23 (25) | 29 (32) | 44 (49) | 23 (26) | 23 (26) | ||

| High | 99 (39) | 21 (21) | 27 (28) | 50 (51) | 35 (36) | 36 (27) | 37 (38) | ||

adjusted for age, education, income, household composition and employment status

Figure 1.

BMI Changes at each Time Point by Lagged Emotional Eating.

Figure 2.

WC Changes at each Time Point by Lagged Emotional Eating

RESULTS:

Characteristics of study participants as well as associations with EWD and ETMS are shown in Table 1. Participants averaged 44 years of age, and the majority (81%) had at least some college education. One-third of the study population had incomes above $40,000, and 21% had incomes of less than $20,000 per year. Over 75% were employed full-time and 12% were unemployed. Mean BMI of the sample was 36 kg/m2; 22% of women were classified as overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2), and 30%, 26% and 21%, respectively, were measured with weight consistent with class I (BMI 30–34.9 kg/m2), class II (BMI 35–39.9 kg/m2), and class III obese (BMI≥ 40kg/m2) (not shown).

EWD and ETMS were reported as “Almost Always,” or, “often” by 37% and 26% of respondents respectively. There were no significant associations between baseline levels of EWD or ETMS and any demographic characteristics (Table 1). Reported stress was associated with higher reported EWD and ETMS. For EWD, 51% of those with high stress reported always or often EWD, and 21% reported rarely or never EWD. Also, 22% of women with low stress reported always or often EWD and 43% reported rarely or never EWD (p<0.0001). For ETMS, 38% of women with high stress reported always or often ETMS and 36% reported rarely or never ETMS; only 11% of those with low stress reported always or often ETMS, and 67% reported rarely or never ETMS (p<0.001).

At baseline, BMI and WC differed based on reported emotional eating. Women reporting rarely or never EWD had significantly lower BMI (34 kg/m2) and WC (98 cm) compared with women reporting almost always or often EWD (37 kg/m2 p<.01 and 105 cm respectively), p<.05 for both. Women reporting rarely or never ETMS had significantly lower BMI (35 kg/m2) and WC (99 cm) compared with women who reported almost always or often ETMS (38 kg/m2, p<.01 and 106 cm respectively, p<.05).

The lagged associations of EWD and ETMS for changes in BMI and WC, respectively, are shown in (Figures 1 & 2). Decreased BMI and WC at 3 months were observed at all levels of baseline EWD and ETMS, but did not differ across the ETMS or EWD categories. BMI increased significantly to levels above baseline at 12 months among women in the always/often category for both 8 month EWD (0.91 kg/m2; p<0.01) and 8 month ETMS (1.1 kg/m2; p<0.01), but remained below baseline (between −0.51 to −1.0 kg/m2) in the lower EWD and ETMS categories. Decreases were seen in WC at 3 months across all categories of baseline EWD and ETMS. Attenuation of initial decreases in WC at 8- and 12-months among women in the highest categories of EWD and EMTS at the prior visits was suggested (Figure 2), but not significant. No association was found for reported stress level with BMI or WC at any time point of the study (Data not shown).

DISCUSSION:

These analyses suggest that emotional eating influences the BMI and WC outcomes experienced by Black women in a culturally-tailored weight control program. As found previously among this sample,18 EWD and ETMS were associated with BMI and WC at baseline, and both EWD and ETMS were associated with later BMI change. Most importantly, we found that although Black women who reported frequent EWD and to a lesser extent, ETMS, experienced decreased BMI and WC initially along with other women, by the end of the study they experienced regain to BMI levels above their baseline measures. A similar but weaker and, non-significant pattern was observed for WC. Thus, the effect of emotional eating may be especially important during the maintenance phase of weight loss.

Emotional eating in response to stress may be curtailed during the intensive phase of intervention, but once contact frequency is tapered, potential effects of emotional eating may become more influential. Given that Black women tend to have smaller initial weight loss than white counterparts in most weight loss studies,12 effective maintenance for more modest weight loss may be critical. These results suggest that ways to provide skills to manage emotional eating should be a focus of future weight control intervention research with Black women. Such approaches could support weight maintenance and prevention of regain, which is the bane of efforts to foster long term weight loss.

The cross-sectional association of emotional eating with BMI19 and the findings of BMI change associated with emotional eating are consistent with previous findings,20 however none of these studies were specific to Black women. To our knowledge, the relationship of emotional eating with WC has not been well studied among Black women.21–23 Furthermore, few studies address emotional eating in weight loss interventions. Of those identified, some have found that emotional eating is associated with weight outcomes. 19,20,24,25 Decreases in emotional eating were found to be associated with increased odds of weight loss in a 12 month behavioral weight loss study of 227 adults with overweight. 20 Reduction of emotional eating was also associated in part with weight loss over a 12-month intervention for middle aged women in Portugal, but not associated with weight maintenance at two years.19 This partly supports our findings, but raises questions about whether the effect we observed at 12 months in our sample of Black women would endure.

Frequent emotional eating in our study was reported by a substantial proportion of the women in the intervention—one-third to one fourth—implying increased caloric intake, which has been confirmed among women with obesity in other contexts.26 In particular, emotional eating is associated with consumption of high-density snack foods, particularly sweet and fat-containing foods, which is associated with emotional eating24 and, “stress eating.”27 For Black women, emotional eating has been associated with perceived and race-related stress.4,5,28 Stress as a possible trigger for emotional eating could be an important target for intervention among Black women seeking assistance with weight control.5

The influence of stress on eating behaviors may be due to a behavioral reaction wherein restrained eaters, in times of stress, may become overeaters.29 Further, stress is associated with increasingly ineffective rigid restraint that is typically associated with overeating.30 Indeed, stress—including perceived stress and chronic exposure to stress—is associated with increased drive to eat, disinhibition, intake of nutrient-deficient, comfort foods, and binge-eating.30 Thus, emotional eating among Black women may, in part, function as a coping mechanism for stress that may contribute to overeating.

More broadly, both stressors and behavioral reactions may reflect the environmental contexts in which they occur. It has been suggested that because Black Americans adjust to environmental circumstances such as neighborhood and cultural influences, they may be more likely to eat in response to environmental cues rather than in response to hunger.31 As a population, Black Americans are more likely than White Americans to live in neighborhood environments that are obesogenic and less supportive of healthful eating and physical activity.32

The nature of both EWD and ETMS in Black women warrants further exploration with respect to relevant contexts and triggers. Eating behaviors used for coping, which might include a broader range disordered eating, cannot be addressed in isolation from their determinants.33 A recent review of 13 studies among Black women, found that trauma, stress and discrimination have been associated with binge eating, which is the most common eating disorder.34 This connection has been found previously among Black women with a history of stress, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) who self-identify as, “Strong Black Women,” a cultural ideology associated with emotional inhibition and regulation difficulties.35 These studies document the connection between various types of experienced stress or trauma that have been associated with emotion-related eating changes.

We identified a positive association of both EWD and ETMS with self-reported stress and perceived discrimination in SisterTalk participants at baseline.18 Discrimination or some types of trauma may contribute to stress that leads to eating for reasons other than hunger among Black women. Thus, stress may be a key determinant of emotional eating.

Stress has been found in many studies to be associated with weight and weight loss. Perceived stress was found to be associated with BMI among the large cohort of participants in the Diabetes Prevention Program,36 and has been identified as a barrier to weight loss by others. 37,38 Among African American women, PTSD has been associated with obesity39 and other physical health symptoms.40 Also, among Black participants in the longitudinal Pitt County Study (NC), stress (measured by the perceived stress scale) was associated with BMI increases over the 13 year follow-up.41The reason why we did not observe an association of self-reported stress with baseline or change in BMI or WC in the SisterTalk study are unclear.

This study identifies a potential missing element of weight loss interventions and maintenance strategies in Black women or other populations where frequent emotional eating is an issue. Guidelines for weight loss and weight loss maintenance42 often do not include assessment of stress or emotional eating prior to, or complementing lifestyle intervention. Behavioral treatment has been proposed not just to augment a traditional focus on diet and physical activity, but as the, “first line of intervention,” for individuals with overweight and obesity.43 Identifying and addressing cognitive and emotional factors is a considerable challenge, especially in a group setting.44 This study underscores the need to study how factors such as emotional eating, where relevant, might be addressed to improve success in weight loss and maintenance.

Potential limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting these findings. This study consisted only of Black women from the Boston area who joined a weight control study and may not be relevant to women who do not have overweight, or to women who are not likely to enroll in a weight control program. The sampling approach is also not representative of a defined population of Black women, even those living in the Boston area. Although informative in the context of this study, the measures of EWD and ETMS are not validated.

How stress is measured certainly influences the interpretation of these data, also. The lack of association between weight and perceived stress in the current study may well have been due to the single question we used to measure stress, which has face validity, but not robust or well-defined psychometric properties. Others have found an association between “stress eating,” and BMI,27 in contrast to our lack of finding an association between stress and either BMI or WC. A more comprehensive measure of perceived stress or measures of different types of stress might elicit stronger or clearer relationships with weight status such as stress related to gender, racism, gendered racism, daily hassles, discrimination, etc. Physiologic indicators of stress are also measured in association with weight-related outcomes. In particular, abdominal weight has been found to be associated with stress hormones.29,45 Physiologic measures of stress provide more specific and objective measures of stress reactions, but also increase participant burden considerably.

In conclusion, the emotional eating behaviors observed and quantified in this study were related to weight, perceived stress, and changes in BMI (and to a lesser extent WC) among this sample of Black women. However, the nature of these behaviors, their contextual triggers, and the inter-relationships among them require further study. More detailed measures of stress and/or physiologic stress, contextual triggers of stress such as discrimination and neighborhood environment, and detailed dietary analysis in conjunction with these measures would also add depth for understanding the implications of the eating behaviors identified. From a practical perspective, our findings suggest that those designing weight control programs for Black women should consider assessing emotional eating patterns and evaluate the utility of targeted strategies to address these patterns especially in the maintenance phase.

What is already known about this topic? Emotional eating is associated with higher weight and larger waist circumference in cross-sectional studies, and with less weight loss in prospective studies. Also, Black women have above-average prevalence of obesity and related diseases.

What does your study add? We found that emotional eating may be a significant predictor of weight loss maintenance and greater weight regain among Black women.

How might these results change the direction of research or the focus of clinical practice? Cognitive behavioral skills including managing emotions and related triggers should be evaluated in interventions research with Black women to improve weight loss and maintenance.

Acknowledgements:

The National Cancer Institute provided funding for the design and evaluation of SisterTalk (#R01-CA-74484). We especially acknowledge the irreplaceable contributions and leadership of the Principal Investigator and our mentor, the late Thomas M. Lasater whose vision and tenacity made the SisterTalk study possible.

FUNDING: NIH

Supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author disclosures: P.M. Risica, T. Nelson, S.K. Kumanyika, K.M. Gans. K. Comacho-Orona, G. Bove, A.M. Odoms-Young, no conflicts of interest

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION: NCT02452645

DISCOSURE: “The authors declared no conflict of interest.”

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychological Association AWGoSaHD. Stress and health disparities: Contexts, mechanisms, and interventions among racial/ethnic minority and low-socioeconomic status populations. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuevas AG, Chen R, Slopen N, et al. Assessing the Role of Health Behaviors, Socioeconomic Status, and Cumulative Stress for Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28(1):161–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albert MA, Durazo EM, Slopen N, et al. Cumulative psychological stress and cardiovascular disease risk in middle aged and older women: Rationale, design, and baseline characteristics. Am Heart J. 2017;192:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson JS, Knight KM, Rafferty JA. Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(5):933–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pickett S, Burchenal CA, Haber L, Batten K, Phillips E. Understanding and effectively addressing disparities in obesity: A systematic review of the psychological determinants of emotional eating behaviours among Black women. Obes Rev. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fowler BA, Giger JN. The World Health Organization - Community Empowerment Model in Addressing Food Insecurity in Low-Income African-American Women: A Review of the Literature. Journal of National Black Nurses’ Association : JNBNA. 2017;28(1):43–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharpe PA, Whitaker K, Alia KA, Wilcox S, Hutto B. Dietary Intake, Behaviors and Psychosocial Factors Among Women from Food-Secure and Food-Insecure Households in the United States. Ethn Dis. 2016;26(2):139–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitaker KM, Sharpe PA, Wilcox S, Hutto BE. Depressive symptoms are associated with dietary intake but not physical activity among overweight and obese women from disadvantaged neighborhoods. Nutrition research (New York, NY). 2014;34(4):294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rummo PE, Guilkey DK, Ng SW, Popkin BM, Evenson KR, Gordon-Larsen P. Beyond Supermarkets: Food Outlet Location Selection in Four U.S. Cities Over Time. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(3):300–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogden CL, Fakhouri TH, Carroll MD, et al. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults, by Household Income and Education - United States, 2011–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(50):1369–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzgibbon ML, Tussing-Humphreys LM, Porter JS, Martin IK, Odoms-Young A, Sharp LK. Weight loss and African-American women: a systematic review of the behavioural weight loss intervention literature. Obes Rev. 2012;13(3):193–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Risica PM, Gans KM, Kumanyika S, Kirtania U, Lasater TM. SisterTalk: final results of a culturally tailored cable television delivered weight control program for Black women. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2013;10:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gans KM, Kumanyika SK, Lovell HJ, et al. The development of SisterTalk: a cable TV-delivered weight control program for black women. Prev Med. 2003;37(6 Pt 1):654–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. Journal of psychosomatic research. 1985;29(1):71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown RE, Randhawa AK, Canning KL, et al. Waist circumference at five common measurement sites in normal weight and overweight adults: which site is most optimal? Clin Obes. 2018;8(1):21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson P, Risica PM, Gans KM, Kirtania U, Kumanyika SK. Association of perceived racial discrimination with eating behaviors and obesity among participants of the SisterTalk study. Journal of National Black Nurses’ Association : JNBNA. 2012;23(1):34–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teixeira PJ, Silva MN, Coutinho SR, et al. Mediators of weight loss and weight loss maintenance in middle-aged women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18(4):725–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braden A, Flatt SW, Boutelle KN, Strong D, Sherwood NE, Rock CL. Emotional eating is associated with weight loss success among adults enrolled in a weight loss program. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2016;39(4):727–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chao A, Grey M, Whittemore R, Reuning-Scherer J, Grilo CM, Sinha R. Examining the mediating roles of binge eating and emotional eating in the relationships between stress and metabolic abnormalities. J Behav Med. 2016;39(2):320–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hootman KC, Guertin KA, Cassano PA. Stress and psychological constructs related to eating behavior are associated with anthropometry and body composition in young adults. Appetite. 2018;125:287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez-Cepero A, Frisard CF, Lemon SC, Rosal MC. Association of Dysfunctional Eating Patterns and Metabolic Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease among Latinos. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2018;118(5):849–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konttinen H, Mannisto S, Sarlio-Lahteenkorva S, Silventoinen K, Haukkala A. Emotional eating, depressive symptoms and self-reported food consumption. A population-based study. Appetite. 2010;54(3):473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Strien T, Herman CP, Verheijden MW. Eating style, overeating and weight gain. A prospective 2-year follow-up study in a representative Dutch sample. Appetite. 2012;59(3):782–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallis DJ, Hetherington MM. Stress and eating: the effects of ego-threat and cognitive demand on food intake in restrained and emotional eaters. Appetite. 2004;43(1):39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dressler H, Smith C. Environmental, personal, and behavioral factors are related to body mass index in a group of multi-ethnic, low-income women. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2013;113(12):1662–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Longmire-Avital B, McQueen C. Exploring a relationship between race-related stress and emotional eating for collegiate Black American women. Women Health. 2018:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts CJ, Campbell IC, Troop N. Increases in weight during chronic stress are partially associated with a switch in food choice towards increased carbohydrate and saturated fat intake. European Eating Disorders Review. 2014;22(1):77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groesz LM, McCoy S, Carl J, et al. What is eating you? Stress and the drive to eat. Appetite. 2012;58(2):717–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson DB, Musham C, McLellan MS. From mothers to daughters: transgenerational food and diet communication in an underserved group. J Cult Divers. 2004;11(1):12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duncan SC, Strycker LA, Chaumeton NR, Cromley EK. Relations of neighborhood environment influences, physical activity, and active transportation to/from school across African American, Latino American, and White girls in the United States. International journal of behavioral medicine. 2016;23(2):153–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adam TC, Epel ES. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & behavior. 2007;91(4):449–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goode RW, Cowell MM, Mazzeo SE, et al. Binge eating and binge-eating disorder in Black women: A systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(4):491–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrington EF, Crowther JH, Shipherd JC. Trauma, binge eating, and the “strong Black woman”. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(4):469–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delahanty LM, Meigs JB, Hayden D, Williamson DA, Nathan DM. Psychological and behavioral correlates of baseline BMI in the diabetes prevention program (DPP). Diabetes care. 2002;25(11):1992–1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West DS, Elaine Prewitt T, Bursac Z, Felix HC. Weight loss of black, white, and Hispanic men and women in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(6):1413–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cho JH, Jae SY, Choo I, Choo J. Health‐promoting behaviour among women with abdominal obesity: a conceptual link to social support and perceived stress. Journal of advanced nursing. 2014;70(6):1381–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitchell KS, Aiello AE, Galea S, Uddin M, Wildman D, Koenen KC. PTSD and obesity in the Detroit neighborhood health study. General hospital psychiatry. 2013;35(6):671–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iverson KM, Pogoda TK, Gradus JL, Street AE. Deployment-related traumatic brain injury among Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans: associations with mental and physical health by gender. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(3):267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fowler-Brown AG, Bennett GG, Goodman MS, Wee CC, Corbie-Smith GM, James SA. Psychosocial stress and 13-year BMI change among blacks: the Pitt County Study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(11):2106–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S102–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Butryn ML, Webb V, Wadden TA. Behavioral treatment of obesity. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011;34(4):841–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wadden TA, Tronieri JS, Butryn ML. Lifestyle modification approaches for the treatment of obesity in adults. Am Psychol. 2020;75(2):235–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duclos M, Marquez Pereira P, Barat P, Gatta B, Roger P. Increased cortisol bioavailability, abdominal obesity, and the metabolic syndrome in obese women. Obes Res. 2005;13(7):1157–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]