Abstract

Background

The volume of health-related publications on Syria has increased considerably over the course of the conflict compared with the pre-war period. This increase is largely attributed to commentaries, news reports and editorials rather than research publications. This paper seeks to characterise the conflict-related population and humanitarian health and health systems research focused inside Syria and published over the course of the Syrian conflict.

Methods

As part of a broader scoping review covering English, Arabic and French literature on health and Syria published from 01 January 2011 to 31 December 2019 and indexed in seven citation databases (PubMed, Medline (OVID), CINAHL Complete, Global Health, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus), we analyzed conflict-related research papers focused on health issues inside Syria and on Syrians or residents of Syria. We classified research articles based on the major thematic areas studied. We abstracted bibliometric information, study characteristics, research focus, funding statements and key limitations and challenges of conducting research as described by the study authors. To gain additional insights, we examined, separately, non-research publications reporting field and operational activities as well as personal reflections and narrative accounts of first-hand experiences inside Syria.

Results

Of 2073 papers identified in the scoping review, 710 (34%) exclusively focus on health issues of Syrians or residents inside Syria, of which 350 (49%) are conflict-related, including 89 (25%) research papers. Annual volume of research increased over time, from one publication in 2013 to 26 publications in 2018 and 29 in 2019. Damascus was the most frequently studied governorate (n = 33), followed by Aleppo (n = 25). Papers used a wide range of research methodologies, predominantly quantitative (n = 68). The country of institutional affiliation(s) of first and last authors are predominantly Syria (n = 30, 21 respectively), the United States (n = 25, 19 respectively) or the United Kingdom (n = 12, 10 respectively). The majority of authors had academic institutional affiliations. The most frequently examined themes were health status, the health system and humanitarian assistance, response or needs (n = 38, 34, 26 respectively). Authors described a range of contextual, methodological and administrative challenges in conducting research on health inside Syria. Thirty-one publications presented field and operational activities and eight publications were reflections or first-hand personal accounts of experiences inside Syria.

Conclusions

Despite a growing volume of research publications examining population and humanitarian health and health systems issues inside conflict-ravaged Syria, there are considerable geographic and thematic gaps, including limited research on several key pillars of the health system such as governance, financing and medical products; issues such as injury epidemiology and non-communicable disease burden; the situation in the north-east and south of Syria; and besieged areas and populations. Recognising the myriad of complexities of researching active conflict settings, it is essential that research in/on Syria continues, in order to build the evidence base, understand critical health issues, identify knowledge gaps and inform the research agenda to address the needs of the people of Syria following a decade of conflict.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13031-021-00384-3.

Introduction

The armed conflict in Syria is commonly described as being among the most extensively studied and documented of contemporary conflicts [1]. There is an expanding volume of literature on a diverse range of health issues relating to the conflict, from attacks on healthcare and use of chemical weapons to refugee health status assessment. Research in and on active conflict zones is inherently difficult, and these challenges are reflected in the focus, nature and volume of research outputs produced while an armed conflict is ongoing. For example, while the challenges facing the health systems of countries hosting large numbers of Syrian refugees have been documented [2, 3], research assessments of the fragmented health system(s) inside war-torn Syria are limited. Similarly, compared with populations inside Syria, Syrian refugee populations are more accessible and therefore have received comparatively more research attention, including reviews and syntheses of this large volume of published research [4].

The Lancet - American University of Beirut Commission on Syria is an international research collaboration launched in December 2016 to analyse the Syrian conflict, its toll and the international response through a health and wellbeing lens, and to propose a set of recommendations to address current and future needs, inform rebuilding efforts and drive accountability [5]. To inform its work, the Commission has conducted a number of literature reviews. A paper examining clinical, biomedical, public health and health systems articles on Syria published between 1991 and 2017 reported that compared with the pre-conflict period (i.e. pre-2011), over the course of the conflict the number of health-related publications increased while the rate, type, topic and local authorship of publications changed. News, commentaries and editorial publications and not research largely drove the increase in publication volume during the conflict period [6]. Whilst non-research publications are crucial to raise awareness, rapidly disseminate information and inform advocacy during active conflicts, research in/on active war zones is also essential. To the best of our knowledge, a detailed thematic overview of conflict-related research on health inside Syria has not been published. Such a review is important to understand what themes, population subgroups and geographic areas have been examined, allowing identification of knowledge gaps to inform the health research agenda. In this paper, we aim to characterise conflict-related population and humanitarian health and health systems research focused inside Syria and published over the course of the conflict.

Methods

Search strategy

This study is a sub-analysis of a broader scoping review of literature published between 2011 and 2019 and examining human health and Syria or Syrians, including studies of refugees and multi-country publications that include but are not exclusively limited to Syria. This review is different to, and complements, the prior review by Abdul-Khalek et al. [6] in that it covers a larger set of issues, has a broader geographical scope (inside Syria, outside Syria, multicountry settings including Syria), covers exclusively the conflict years and over a longer time-span of the conflict, and has specifically examined publications by conflict and non-conflict-related status. The search strategy for the broader scoping review is provided in the Additional file 1. Briefly, the broader scoping review searched for literature on human health and Syria or Syrians published in English, Arabic or French from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2019 and indexed in seven bibliographic and citation databases (PubMed, Medline (OVID), CINAHL Complete, Global Health, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus). After de-duplication, 13,699 records were identified. Two-stage screening against pre-specified criteria by at least two reviewers, review of reference lists and review of additional papers known to the authors resulted in a total of 2073 relevant publications.

For this current analysis, we examined only conflict-related research papers that studied health issues inside Syria and focused on Syrians or residents in Syria (e.g. Palestinian or Iraqi refugees). We defined conflict-related publications as those examining the Syrian conflict, its effects or the conflict response. We defined research papers as publications of any type (including traditional research papers, letters, commentaries and other) that report on the primary collection of data, or the secondary analysis and interpretation of existing data. We therefore excluded review publications and literature syntheses, as well as non-conflict related publications (e.g. biomedical or genomic studies conducted during the war but not related to the Syrian conflict, its effects or the conflict response), clinical case studies and case series, conflict-related studies focused only on Syrians outside Syria (e.g. studies of Syrian refugees or studies of war casualties evacuated for treatment in neighbouring countries), and studies conducted in multiple countries that include Syria as one of any number of study countries. Field and operational activities publications, defined as papers describing operational activities or organizational field experiences inside Syria but not presenting research per se (e.g. papers describing set-up of a field facility and number of patients seen, or describing humanitarian operations), which provide important insights or data about health issues inside Syria during the conflict, were considered separately to the research papers. Similarly, personal reflections and narrative accounts of first-hand experiences inside Syria were considered separately. News reports and news interviews with personnel inside Syria were not included in this analysis.

Literature dataset analysis

We classified research articles into six categories based on the major thematic areas studied: mortality; population health status; health determinants and risks (including behavioural, physiological, environmental and social determinants of health); humanitarian assistance, response or needs (including any studies conducted by humanitarian agencies or analysis of services provided by humanitarian actors); health system (including papers examining any of the six health system pillars as defined by the World Health Organization [7], namely service delivery (unless delivered by humanitarian actors), health workforce, health information systems, medical products, financing, governance); and war strategies & alleged international humanitarian law (IHL) violations (including studies reporting on warfare, besiegement and related human rights violations, attacks on civilian infrastructures such as health facilities, and publications on chemical attacks). A single paper could be classified into multiple thematic categories if it had a major focus on more than one theme.

For each paper, at least one reviewer abstracted bibliometric information and study characteristics (including study description, study period, methodology, governorates/ geographic location of the study, study population, country of affiliation(s) of first and last authors, type of institutional affiliation(s) of first and last authors). We also extracted qualitative data on selected key limitations and challenges of conducting research as described by the authors, and categorized these as contextual (which we defined as including issues of safety, accessibility, stakeholder engagement and cultural considerations), methodological (including issues related to design and conduct of the study) or administrative (including issues related to research permits and permissions, logistics, research capacity). Where available, funding statements were also reviewed and assigned to one of three categories (funded, not funded, not reported). Classification of each paper was discussed by three reviewers.

We used basic descriptive statistics to summarise key bibliometric characteristics of the research papers and changes in the volume and focus of research over time. Key challenges encountered were summarized narratively.

Results

Among the 13,699 records initially identified through the full scoping review, 2073 papers were considered relevant to human health and Syria. For this conflict-related research subanalysis, we excluded clinical case reports and case series (n = 169), publications that examined multiple countries of which Syria was one (n = 268), publications that studied Syrians outside Syria (n = 924), publications focussed inside Syria but not related to the conflict (n = 359) and conflict-related publications focussed inside Syria that were not research publications, personal reflections or descriptions of field and operational activities (n = 225). This resulted in a total of 89 conflict-related research publications focused inside Syria, which form the dataset of this analysis. These conflict-related research papers were all published in English. We also identified 31 English-language field and operational activities papers focused on health inside Syria and eight personal narrative reflections, which we examine separately.

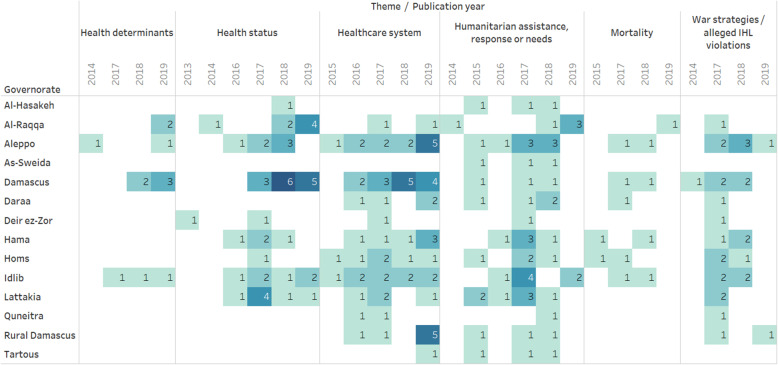

Table 1 presents summary characteristics of the 89 conflict-related research papers. The conflict in Syria started in 2011 but there were no conflict-related research papers published during 2011–2012. Thereafter the annual volume of research increased over time, from one publication in 2013, three in 2014, to 26 publications in 2018 and 29 in 2019. There is considerable variation in the governorates studied by thematic focus and over time (Table 1, Fig. 1). Damascus is the most frequently studied governorate (n = 33), followed by Aleppo (n = 25), Idlib (n = 20), Lattakia (n = 15) and Hama (n = 14). Deir Al Zour (n = 3), Quenietra (n = 3) and As-Sweida (n = 3) are the least frequently studied. Twelve papers have a national scope. Several papers do not identify specific governorates, instead referring to the controlling factions, describing for example opposition-controlled territories generally. There are no papers on health in areas while controlled by the so-called Islamic State (IS).

Table 1.

Characteristics of conflict-related research studies on health inside Syria by research theme, January 2011–December 2019

| Total number of research publications | THEMEa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health status | Mortality | Health determinants and risks | Humanitarian assistance, response or needs | Health system | War strategies & alleged IHL violations | ||

| Publication year | |||||||

| 2011–2013 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2014–2016 | 18 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 2 |

| 2017–2019 | 70 | 31 | 8 | 11 | 20 | 26 | 12 |

| Locationb | |||||||

| By governorate | |||||||

| Al-Hasakeh | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Al-Raqqa | 8 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| Aleppo | 25 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 12 | 6 |

| As-Sweida | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Damascus | 33 | 14 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 14 | 5 |

| Daraa | 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Deir ez-Zor | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hama | 14 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 3 |

| Homs | 12 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 3 |

| Idlib | 20 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 9 | 4 |

| Lattakia | 15 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 2 |

| Quneitra | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Rural Damascus | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 2 |

| Tartous | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| By regiong | |||||||

| National/ whole of Syria | 12 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 4 |

| Border with Turkey/ North-west Syria | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Non-government-controlled areas (governorates not specified) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Opposition controlled areas (governorates not specified) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Not reported | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| First author’s country of institutional affiliation e | |||||||

| Syria | 30 | 21 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 0 |

| USA | 25 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 11 | 6 |

| UK | 12 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 2 |

| Belgium | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Lebanon | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Turkey | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Otherc | 15 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Not stated | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| First author’s institutional affiliationf | |||||||

| Academic | 69 | 26 | 7 | 9 | 15 | 27 | 13 |

| Clinical | 7 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Governmental | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Humanitarianh | 14 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 0 |

| Independant | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Military | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Think tank/ research organization | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| United Nations agency | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Senior (last) author’s country of institutional affiliation e | |||||||

| Syria | 21 | 15 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| USA | 19 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 8 |

| UK | 10 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| Lebanon | 7 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Belgium | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Turkey | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Otherd | 24 | 15 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 3 |

| Not applicable | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Not stated | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Senior (last) author’s institutional affiliationf | |||||||

| Academic | 65 | 29 | 8 | 8 | 13 | 26 | 11 |

| Clinical | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Governmental | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Humanitarianh | 13 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 0 |

| Independant | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Military | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| United Nations agency | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Not applicable | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Methodology | |||||||

| Primary quantitative | 40 | 20 | 1 | 9 | 13 | 13 | 2 |

| Secondary quantitative | 28 | 15 | 9 | 0 | 5 | 11 | 7 |

| Qualitative | 15 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 4 |

| Mixed methods | 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Research funding | |||||||

| Funded | 37 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 14 | 11 | 7 |

| Not funded | 28 | 17 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 5 |

| Not reported | 24 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 13 | 2 |

a Some studies cover multiple themes

b Due to the fluid nature of the conflict and inconsistencies in reporting of study locations, we report here the governorates whenever they are reported by the study authors, regardless of political control (i.e. opposition-controlled, government-controlled or non-government-controlled). When the governorates are not specified but the political control of the study setting is reported by study authors, it is recorded as such in this table. Some studies report neither the political control nor the governorates, and these are denoted as ‘not reported’. Some studies cover multiple governorates

c Other includes Australia (1), Austria (1), Egypt (2), Israel (1), Japan (1), Qatar (2), Saudi Arabia (2), Spain (2), Switzerland (1), The Netherlands (2)

d Other includes Australia (3), Austria (1), Canada (2), Egypt (1), France (3), Germany (1), India (1), Israel (1), Jordan (2), Qatar (1), Saudi Arabia (2), Singapore (1), Sweden (1), The Netherlands (4)

e Six publications have first authors with multiple affiliations, while seven publications have multiple last author affiliations. Not applicable means there is no senior author (i.e. single author publication). Not stated means there is an author but their affiliation is not mentioned

f Academic institutional affiliations include universities and university-affiliated clinical facilities

gOne study examined remote cross-border operations from the Turkish border city of Gaziantep

hThe humanitarian category denotes humanitarian operational or other nongovernmental organisations

Fig. 1.

Governorates examined in research publications on health inside Syria by themes, January 2011–December 2019

Papers have used a wide range of research methodologies, including primary quantitative methods (n = 40) such as surveys, questionnaires and clinical trials; secondary quantitative data analysis (n = 28) mainly using surveillance system, medical record or program data; and qualitative methodologies (n = 15). Six papers used mixed methods (Table 1).

For the majority of papers, the country of institutional affiliation(s) of first and last (assumed to be the senior) authors are Syria (n = 30, 21 respectively), the United States (n = 25, 19 respectively) or the United Kingdom (n = 12, 10 respectively). For 20 papers (22.4%), both first and last authors had a Syrian affiliation. The institutional affiliation of first authors was predominantly academic (including universities and university hospitals) (n = 69), followed by humanitarian organizations (n = 14), clinical facilities (n = 7), think tank or research organization (n = 2), United Nations (UN) agencies (n = 2), government (n = 1), military (n = 1) and independent (n = 1). The institutional affiliation of senior/ last authors was predominantly academic (n = 65), followed by humanitarian (n = 13) or clinical (n = 7) organisations, with a few senior authors affiliated to governmental or UN agencies (n = 2 for each), and military (n = 1). Of the 37 papers reporting a specific funding source, five listed Syrian universities as the funding source.

Research themes

Table 2 presents detailed summaries of each research paper.

Table 2.

Summary of conflict-related health research studies inside Syria, January 2011–December 2019

| First author (Publication year) | First & Last (Senior) authors’ country of institutional affiliation | Type of institutional affiliation | Description | Theme (Subtheme) | Study Period (month/year) | Methodology | Study Population | Geographic focus | Funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alasaad (2013) [8] |

First: Syria, Switzerland, Spain Last: N/A |

First: academic | Reviews YouTube and social media videos to describe leishmaniasis outbreaks in Deir ez-Zor. | Health status | January–March 2013 | YouTube and Facebook video review, contact with local communities | General population | Deir ez-Zor | Not reported |

| Ahmad (2014) [9] |

First: UK Last: N/A |

First: academic | Assesses the influences of neighborhood socioeconomic position and urban informal settlements on women’s health. | Health determinants and risks | April–May 2011 | Key informant interviews, unstructured observations | Professionals working with populations in informal communities; women in informal settlements | Aleppo | Institute of Health and Society, Newcastle University, UK |

| Hoetjes (2014) [10] |

First: Netherlands Last: Netherlands |

First: humanitarian Last: humanitarian |

Documents results of a screening program and examines food security and factors affecting nutritional status amongst the Tal-Abyad population (Al-Raqqa), and describes MSF nutrition programs. | Health status; humanitarian assistance, response or needs | 2013 | Mixed methods (middle-upper arm circumference screening; qualitative survey) | IDPs living in schools | Al-Raqqa | Not reported |

| Rosman (2014) [11] |

First: Israel Last: Israel |

First: academic/ military Last: academic/ military |

Reports on physician reviews of YouTube videos documenting a sarin attack to determine clinical presentation and review the management of a mass casualty event | War strategies / alleged IHL violations | August–September 2013 | Physician review of YouTube videos | Casualties of Ghouta sarin attack | Damascus | Not reported |

| Alshiekhly (2015) [12] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Evaluates feasibility of Facebook as a teaching modality for a course on medical emergencies in dental practice | Health system (workforce) | March–April 2014 | Pre and post questionnaire | Dental students | Not reported | None |

| Doocy (2015) [13] |

First: USA Last: Belgium |

First: academic Last: academic |

Documents humanitarian needs and priorities among households in need of assistance in accessible communities | Humanitarian assistance, response or needs | April–June 2014 | Needs assessment | General population | Predominantly government-controlled areas (Aleppo, As-Sweida, Damascus, Dara’a, Al-Hasakeh, Homs, Lattakia, Rural Damascus, Tartous) | Humanitarian assistance programs |

| Doocy (2015) [14] |

First: USA Last: USA |

First: academic Last: academic |

Describes trends in internal displacement and analyzes the association between displacement and household well-being and humanitarian needs. | Humanitarian assistance, response or needs | March 2011–June 2014 | Review of published IDP estimates; needs assessment | General population | National | Not reported |

| Guha-Sapir (2015) [15] |

First: Belgium Last: Lebanon |

First: academic Last: academic |

Documents direct conflict-related deaths of women and children using VDC data. | Mortality; war strategies / alleged IHL violations | March 2011–January 2015 | VDC data analysis | Civilians | National | emBRACE—Building resilience amongst communities in Europe & Chatham House |

| Price (2015) [16] |

First: USA Last: USA |

First: humanitarian Last: humanitarian |

Applies capture - recapture methods to data from four sources to estimate mortality, and describes the issues associated with accurately documenting mortality estimates in conflict settings | Mortality | December 2012–March 2013 | Multiple systems estimation / capture -recapture | Civilians and combatants | Homs, Hama | Not reported |

| Sekkarie (2015) [17] |

First: USA Last: USA |

First: clinical Last: academic |

Explores the impact of conflict on dialysis services | Health system (service provision, workforce) | 2013 | Key informant Interviews | Dialysis facility administrators, providers and patients | Non-government-controlled areas (Aleppo, Homs, Idlib) | Not reported |

| Tajaldin (2015) [18] |

First: USA Last: USA |

First: academic Last: academic |

Compares polio case rates using laboratory versus clinical case definitions and different surveillance systems | Health system (information systems); health status | 2013–2014 | Analysis of EWARS and EWARN data | General population | National | Not reported |

| Trelles (2015) [19] |

First: Belgium Last: Belgium |

First: humanitarian Last: humanitarian |

Reports on surgical cases and intraoperative mortality rates at an MSF field hospital | Humanitarian assistance, response or needs | September 2012–January 2014 | Analysis of MSF programme data | Surgical patients | Jabal Al Akrad, Latakia Northwest Syria | Médecins Sans Frontières-Operational Centre, Belgium. |

| Charlson (2016) [20] |

First: Australia, USA Last: Australia, USA |

First: academic Last: academic |

Estimates prevalence of depression and PTSD and models likely current and future mental health service requirements | Health status; Health system (service provision, workforce) | Global Burden of Disease Study 2010, modelling for period 2015–2030 | Global Burden of Disease (GBD) methodology and modelling | General population | National | Queensland Department of Health, Australia |

| El-Khani (2016) [21] |

First: UK Last: UK |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines feasibility of the “bread wrapper approach” which involves distribution of psychological support information on leaflets inserted into bread wraps and using the bread wraps to circulate questionnaires assessing the usefulness of the information provided. | Humanitarian assistance, response or needs | Not reported | Questionnaire | General population | Northern Syria next to the borders with Turkey | The University of Manchester’s ESRC Transformative Research Prize Committee |

| Elsafti (2016) [22] |

First: Qatar, Egypt Last: Belgium |

First: clinical Last: academic |

Documents the family, educational, and health status of Syrian children and associated humanitarian needs | Health status; humanitarian assistance, response or needs | May 2015 | Needs assessment | Children less than 15 years old | Aleppo, Hama, Idlib, Lattakia | None |

| Ismail (2016) [23] |

First: UK Last: Lebanon |

First: academic Last: academic |

Describes trends in tuberculosis, measles and polio case numbers in Syria and challenges of disease surveillance in the conflict context. | Health system (information systems); health status | Peer-reviewed analysis (2005–2015), EWARN & EWARS analysis (2014–2015) | Analysis of EWARN, EWARS data | General population | National | Not reported |

| Jefee-Bahloul (2016) [24] |

First: USA Last: USA |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines attitudes of Syrian healthcare providers towards Store & Forward tele-mental health consultations | Health system (service provision) | Not reported | Online survey | Syrian health-care professionals affiliated with humanitarian NGOs | Aleppo, Damascus, Idlib, Othersa | Not reported |

| Mowafi (2016) [25] |

First: USA Last: France |

First: academic Last: humanitarian |

Assesses the functional status and capacity of trauma hospitals | Health system (service provision, workforce) | February–March 2015 | Survey | Hospitals providing secondary or tertiary surgical care in non-government-controlled areas | Aleppo, Damascus (non-government-controlled area), Dara’a, Hama, Homs, Idlib, Lattakia, Quneitra, Rural Damascus | Yale University & UOSSM. |

| Sparrow (2016) [26] |

First: USA Last: Australia |

First: academic Last: academic |

Compares two infectious disease surveillance systems, the Ministry of Health-run EWARS system and the independent, non-governmental EWARN | Health system (information system); health status | 2014–2015 | Analysis of EWARS and EWARN data | General population | National | Not reported |

| Al-Saadi (2017) [27] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Reports prevalence and risk factors of psychological distress among medical students in Damascus | Health status; Health system (workforce) | November 2015 | Online questionnaire | Second to sixth-year medical students at Damascus University | Damascus | None |

| Alsaied (2017) [28] |

First: USA Last: Canada, Qatar |

First: clinical Last: academic, clinical |

Reports on the operations of UOSSMb primary care clinics in Opposition Territories and reasons for consultations | Humanitarian assistance, response or needs; health status | January 2014–December 2015 | Retrospective administrative database review | Patients seen at 10 primary care centers | Opposition-controlled areas (Aleppo, Deir ez-Zor, Hama, Homs, Idlib, Lattakia) | None |

| Arafat (2017) [29] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: clinical Last: academic |

Describes differences in patterns of injury and mortality rates among patients with penetrating abdominal injuries at Damascus Hospital | Health status | October 2012–June 2013 | Retrospective review of records | Patients with penetrating abdominal injuries | Damascus | None |

| Baaity (2017) [30] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Reports the prevalence of extended spectrum β lactamases of E. coli in isolates from patients in Al-Assad Teaching Hospital, Lattakia | Health status | October 2014–November 2016 | Analysis of data regarding clinical isolates | Patients in Al-Assad teaching hospital | Lattakia | Not reported |

| Cummins (2017) [31] |

First: Not stated Last: Turkey |

First: humanitarian Last: humanitarian |

Aims to understand the impact of providing food kits in Idlib and how it disturbs the food market, and proposes market-based approach as an alternative for food aid provision. | Humanitarian assistance, response or needs | 2016 | Interviews | Community members in Idlib (Darkoush and Salquin) | Idlib | UK Department for International Development (DFID) through the Urban Crises Learning Fund. |

| Diggle (2017) [32] |

First: UK Last: UK |

First: humanitarian Last: academic |

Reflects on operational experiences and analyses humanitarian health response data collected in contested and opposition-held areas of Syria | Mortality; health status; humanitarian assistance, response or needs | 2013–2014 | Analysis and review of data from multiple operational databases | Civilians & combatants | Contested and opposition-controlled areas (governorates not specified) | None |

| Doocy (2017) [33] |

First: USA Last: USA |

First: academic Last: academic |

Identifies humanitarian needs and priorities among displaced and female headed households in government-controlled areas | Humanitarian assistance, response or needs | April–June 2016 | Needs assessment | Displaced & female headed households | Government-controlled areas (Aleppo, As-Sweida, Damascus, Dara’a, Hama, Al-Hasakeh, Homs, Lattakia, Rural Damascus, Tartous) | US-based international nongovernmental organization |

| Doocy (2017) [34] |

First: USA Last: Turkey |

First: academic Last: humanitarian |

Examines the effectiveness of three assistance programs (in-kind food commodities, food vouchers, unrestricted vouchers) in improving food security in northern Syria. | Humanitarian assistance, response or needs; Health determinants and risks | September–December 2014, May/June 2015 | Serial household surveys, shopkeeper survey and analysis of program monitoring data | Beneficiary households; shopkeepers participating in the voucher program | Idlib | GOAL |

| Elamein (2017) [35] |

First: Turkey Last: Turkey, Egypt |

First: UN agency Last: UN agency, academic |

Describes the first operational use of the Monitoring Violence against Health Care (MVH) tool to report real-time incident data for attacks on healthcare infrastructure, workers and patients | War strategies / alleged IHL violations; health system (service provision; workforce) | November 2015–December 2016 | Analysis of MVH data | Healthcare workers, health service users | Aleppo, Al-Raqqa, Damascus, Dara’a, Deir ez-Zor, Hama, Homs, Idlib, Lattakia, Quneitra, Rural Damascus | None |

| Fouad (2017) [36] |

First: Lebanon Last: Lebanon |

First: academic Last: academic |

Reports on attacks on healthcare and experiences of health workers inside Syria | War strategies / alleged IHL violations; health system (workforce; service provision) | Not reported | Mixed methods study (quantitative data analysis, consultations, testimonials) | Health workers | National | IDRC; American University of Beirut |

| Fujita (2017) [37] |

First: Japan Last: Sweden |

First: academic Last: academic |

Presents daily time series analysis of violent deaths in Syria, including temporal and spatial analysis, and compares trends with those of violent and non-violent deaths in the non-conflict context of England | Mortality | 1200-day period commencing 500 days post conflict onset | Secondary analysis and modelling of Violations Documentation Center data | Civilians and military personnel | Aleppo, Damascus, Dara’a, Homs, Idlib | Bilateral Joint Research Project between JSPS, Japan, and FRS-FNRS, Belgium. Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from MEXT Japan |

| Hawat (2017) [38] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Reviews the epidemiology of cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis in Lattakia and examines the effects of the Syrian conflict on incidence | Health status | 2006–2016 | Analysis of Leishmaniasis and Contagious Diseases Centre data for new cases of leishmaniasis | General population | Lattakia | Not reported |

| Mohammad (2017) [39] |

First: Syria Last: Canada |

First: academic Last: clinical, academic |

Assesses asthma prevalence, asthma control and quality of life among those with diagnosed asthma; Among non-asthmatics, estimates prevalence of respiratory symptoms, PTSD symptoms and other chronic disease co-morbidities. |

Health status | Not reported | Cross-sectional survey | IDPs in Al-Herjalleh shelter aged > = 5 years | Damascus | Syrian Private University |

| Sahloul (2017) [40] |

First: USA Last: USA |

First: academic Last: clinical |

Examines quality of cancer care and needs in government-controlled areas versus besieged areas, and provision of care in general clinics compared with specialized cancer care clinics. | Health system (service provision, workforce); war strategies / alleged IHL violations | Not reported | Cross-sectional survey | Oncologists and surgeons working in cancer clinics, and general physicians | Government-controlled areas (Damascus, Lattakia, Homs, and West Aleppo) and besieged areas (East Ghouta, East Aleppo, and Idlib) | Not reported |

| van Berlaer (2017) [41] |

First: Belgium Last: Belgium |

First: academic Last: academic |

Documents diagnoses, injuries and comorbidities in children in Northern Syria | Health status; humanitarian assistance, response or needs | May 2015 | Cross-sectional household survey | Children younger than 15 years | Aleppo, Hama, Idlib, Lattakia | None |

| Abbas (2018) [42] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines efficacy and feasibility of peer- led versus professional-led training in basic life support course for medical students | Health system (workforce) | April 2016 | Randomized controlled trial | Medical students in pre-clinical years at Syrian Private University | Damascus | None |

| Albaroudi (2018) [43] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines prevalence of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in children and socioeconomic associations, and effectiveness of oral iron supplements | Health status; health determinants and risks |

1) Retrospective part: November 2011–November 2015 2) Prospective part: 2 month period, not specified |

Retrospective medical record review; parental questionnaire & clinical data analysis | Children seen at primary care clinics at the Children’s Hospital in Damascus | Damascus | Damascus University |

| Ballouk (2018) [44] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic, government |

Assesses gingival health status in children aged 8–12 years in Damascus city | Health status | September 2016–January 2017 | Cross-sectional, school-based oral health survey | Children aged 8–12 years | Damascus | None |

| Chen (2018) [45] |

First: USA Last: USA |

First: academic Last: academic |

Estimates the number of unique identifiable deaths in the Syrian conflict by deduplicating four datasets | Mortality; war strategies and alleged IHL violations | March 2011–April 2014 | Unique entity estimation using mortality data from VDC, SNHR, CSR-SY, SSc | Civilians and combatants | Not reported | National Science Foundation (NSF), Amazon Research Award, Laboratory for Analytic Sciences (LAS). |

| Darwish (2018) [46] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Reviews pediatric chest injuries treated in the Mouassat University Hospital in Damascus before and during the Syrian crisis | Health status | January 2005–December 2016 | Hospital record review | Pediatric chest trauma patients | Damascus | None |

| de Lima Pereira (2018) [47] |

First: Syria Last: Netherlands |

First: humanitarian Last: humanitarian |

Assesses vaccine-preventable disease risk and vaccination needs, and vaccination coverage following an immunization program | Humanitarian assistance, response or needs; health status | June–September 2015 | Cross-sectional household survey | Children < 5 years old | Aleppo | None |

| Doocy (2018) [48] |

First: USA Last: USA |

First: academic Last: academic |

Assesses humanitarian needs in government-controlled areas of Syria | Humanitarian assistance, response or needs | April – June 2016 | Needs assessment | General population | Government-controlled areas (Aleppo, As-Sweida, Damascus, Dara’a, Hama, Al-Hasakeh, Homs, Lattakia, Rural Damascus, Tartous) | US-based international nongovernmental organization |

| Footer (2018) [49] |

First: USA Last: USA |

First: academic Last: academic |

Explores the impact of the Syrian conflict on health workers and healthcare in opposition-controlled areas and challenges faced, including in responding to chemical weapons attacks | Health system (service provision, workforce); war strategies / alleged IHL violation | October 2014 (Gaziantep), July–August 2017 (online) | Semi-structured interviews | Health-care professionals with experience in opposition-controlled areas of Syria | Opposition- controlled areas (governorates not specified) | MacArthur Foundation |

| Garry (2018) [50] |

First: UK Last: UK |

First: academic Last: academic |

Explores factors impacting provision of healthcare for NCDs in opposition-controlled Syria | Humanitarian assistance, response or needs | June–August 2017 | Semi-structured interviews | Humanitarian healthcare staff or Syrian health workers from opposition-controlled / contested areas | Opposition-controlled areas (governorates not specified) | UK Research and Innovation (Global Challenges Research Fund) |

| Guha-Sapir (2018) [51] |

First: Belgium Last: USA |

First: academic Last: academic |

Reports demographic, spatial, and temporal patterns of direct deaths among civilians and opposition combatants using VDC data | Mortality; war strategies / alleged IHL violations | March 2011–December 2016 | VDC data analysis | Civilians and combatants | Non-government-controlled areas (governorates not specified) | None |

| Haar (2018) [52] |

First: USA Last: USA |

First: academic Last: academic |

Describes a standardized field survey tool for documenting attacks on healthcare, and compares this dataset to PHR’s database that uses open sources to track attacks on health facilities | War strategies / alleged IHL violations; health system (service provision, workforce) | 2016 | Development of prospective surveillance methodology, standardized reporting questionnaire | NA | Aleppo, Hama, Homs, Idlib | MacArthur Foundation, the Oak Foundation, Berkeley Research Impact Initiative |

| Idris (2018) [53] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Reports prevalence of cigarette smoking among university students and examines the impact of war on smoking behavior | Health determinants and risks | May 2015 | Online cross-sectional survey | Undergraduate students at Damascus University. | Damascus | None |

| Khamis (2018) [54] |

First: Syria Last: Lebanon |

First: government Last: academic |

Reports National AIDS Program data and examines how the war affected HIV surveillance and voluntary counselling and testing | Health status; health system (service provision) | 2010–2016 | Secondary analysis of National AIDS Program surveillance data | General population | National | Not reported |

| Kubitary (2018) [55] |

First: Syria Last: Syria, France |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines validity of the Arabic version of the two-question Quick Inventory of Depression (QID-2-Ar) in Syrian multiple sclerosis patients. | Health status | Not reported | Cross-sectional study | Multiple sclerosis patients aged 18–60 years seen at two hospitals | Damascus | None |

| Kubitary (2018) [56] |

First: Syria Last: France, Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines the effects of Therapy by Repeating Phrases of Positive Thoughts (TRPPT) on PTSD, Sleep Disorder and War Experiences among school children and adolescents | Health systems (service provision); health status | Not reported | Clinical trial | Children & adolescents aged 13–17 years | Damascus | Not reported |

| Meiqari (2018) [57] |

First: Netherlands Last: Netherlands |

First: humanitarian, academic Last: humanitarian |

Describes the impact of the war on child health in Tal Al-Abyad and Kobane, using available medical and humanitarian data from Médecins Sans Frontières | Health status; humanitarian assessment, response or needs | April 2013–September 2016 | Analysis of MSF clinical data and reports | Children < 5 years old who attended an MSF facility | Aleppo, Al-Raqqa | Not reported |

| Morrison (2018) [58] |

First: UK Last: N/A |

First: academic | Reports the experiences and challenges of health service delivery under siege | Health system (service provision); war strategies / alleged IHL violations | Mid-2016 | Interviews and focus group discussions | Interim Council and healthcare professionals in four besieged urban areas | Opposition-controlled areas (Aleppo, Damascus) | DFID’s Urban Crises Programme |

| Othman (2018) [59] |

First: Not stated Last: Australia |

First: independent Last: academic |

Evaluates the impact of a six-month programme to address organizational stressors and promote staff-care and social support | Health determinants and risks; health system (workforce) | Not reported | Evaluation research/ Implementation research | Staff working for a psychosocial support organization | Non-government-controlled areas (Idlib) | Not reported |

| Perkins (2018) [60] |

First: UK Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Reports the incidence of psychological symptoms among school-aged children in Damascus and Lattakia | Health status | Not reported | Cross-sectional study | School children (8–15 years old) | Damascus, Lattakia | Not reported |

| Rehman (2018) [61] |

First: Austria Last: Germany; Austria |

First: academic Last: academic, clinical |

Describes the leishmaniasis surveillance control program | Health status |

November 2014– February 2016 |

Molecular–epidemiologic survey of cutaneous leishmaniasis in sentinel sites | General population (including IDPs) | Northern Syria (Aleppo, Idlib, Hama, Al-Raqqa, and Al-Hasakeh) | USAID & DFID |

| Rodriguez-Llanes (2018) [62] |

First: Belgium Last: USA |

First: academic Last: academic |

Reports demographic characteristics of victims of chemical weapons attacks | War strategies / alleged IHL violations; mortality | March 2011–April 2017 | VDC data analysis | Deceased victims of chemical weapons attacks | Non-government-controlled areas (Aleppo, Damascus, Hama, Idlib) | None |

| Sawaf (2018) [63] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Explores medical students’ attitudes and factors affecting their specialty choices and career plans | Health system (workforce) | August 2016 | Self- administered questionnaire | Medical students at three universities in Damascus | Damascus | Syrian Private University |

| Sikder (2018) [64] |

First: USA Last: Jordan |

First: academic Last: independent |

Assesses the effectiveness of a multilevel risk reduction intervention in maintaining Free Chlorine Residual in household drinking water | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs | January 2018 | Cross-sectional study using interviews & observations; water quality testing | Chlorination station operators, well owners, households, Methology | Opposition-controlled areas in southern Syria (governorates not specified) | WoS (Amman hub) WASH Sector, UNICEF, UNICEF/NYC and Tufts University |

| Sikder (2018) [65] |

First: USA Last: Jordan |

First: academic Last: UN agency |

Examines WASH access and needs in opposition controlled southern Syria | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs | June/July 2016–February 2017 | Cross-sectional household surveys & water quality testing | Households | Opposition-controlled areas (Dara’a, Quneitra) | WoS (Amman hub) WASH Sector |

| Turk (2018) [66] |

First: Syria Last: USA |

First: academic Last: academic |

Assesses medical students attitudes toward research | Health system (workforce) | Not reported | Self-administered questionnaire | Medical students at University of Damascus | Damascus | None |

| Wong (2018) [67] |

First: USA Last: USA |

First: academic Last: clinical |

Reviews attacks on ambulances | War strategies / alleged IHL violations; health system (service provision) | January 2016–December 2017 | Secondary data analysis on individual attacks reported by SNHR | NA | National | None |

| Ahmad (2019) [68] |

First: UK Last: UK |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines perceptions of married women living in low-income formal and informal neighborhoods in Aleppo on the effects of neighbourhood on their health and well-being | Health determinants and risks | April–June 2011 | Semi-structured interviews | Married women living in informal and low-income formal neighbourhoods | Aleppo | European Commission FP7 programme grants MedCHAMPS and RESCAP-MED |

| Abu Salem (2019) [69] |

First: Lebanon Last: Lebanon |

First: academic Last: academic |

Uses VDC data to confirm conflict events and identify fake news in FA-KES, a fake news dataset | Mortality | Not reported | Analysis of news articles and reports on incidence of deaths compared to VDC dataset | General population | National | American University of Beirut |

| Alaryan (2019) [70] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Reports on prescription drug misuse in Damascus and Damascus countryside during the conflict | Health system (medical products) | December 2016–March 2017 | Cross-sectional survey | Community pharmacists | Damascus and Rural Damascus | Not reported |

| Alhaffar (2019) [71] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: clinical |

Examines prevalence of burnout syndrome among resident physicians in training | Health system (workforce) | July 2018 | Online questionnaire | Resident physicians in training from 12 hospitals in 8 governorates who spent at least one year in a residency program approved by the Syrian Commission of the Medical Specialties. | Damascus, Aleppo, Lattakia, Tartous, Dara’a, Rural Damascus, Hama, Homs | Not funded (self-funded) |

| Alhaffar (2019) [72] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines the prevalence of caries and oral health status among school children in Damascus, and associations with socio-economic status | Health status; Health determinants and risks | September–November 2017 | School-based survey (questionnaire and clinical examination) | Seventh-grade school children in 10 randomly selected schools covering Damascus city | Damascus | Not funded (self-funded) |

| Alhammoud (2019) [73] |

First: Qatar Last: UK |

First: clinical Last: clinical |

Reports the experience of one field hospital in Aleppo providing treatment of open shaft fractures | Health system (service provision) | July 2011–July 2016 | Retrospective medical record review | Patients with open long bone fractures managed with external fixation | Aleppo | Not reported |

| Alothman (2019) [74] |

First: Syria Last: India |

First: academic Last: academic |

Reports on war injury presentations to Hama National Hospital | Health system (service provision) | 2017 | Retrospective medical record review | War injured patients received by Hama National Hospital | Hama | Not reported |

| Ballouk (2019) [75] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic, government |

Examines prevalence of dental caries among school-aged children in Damascus city | Health status | September 2016–January 2017. | School based oral health survey (clinical examination) | School children aged 8–12 years and resident in Damascus city during the study period | Damascus | Not funded (self-funded)d |

| Blackwell (2019) [76] |

First: USA Last: not stated |

First: humanitarian Last: humanitarian |

Examines the impact of a cash-based assistance program on women’s empowerment and violence against women | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs; health status | March–August 2018 | Semi-structured interviews | Woman aged 18–59 who received a cash payment over a three-month period | Al-Raqqa | UK Department for International Development (DFID) |

| Douedari (2019) [77] |

First: UK Last: UK |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines perceptions of local health providers and service users regarding health system governance, roles and relationships of institutional actors, and challenges and potential solutions | Health system (governance) | July–August 2016 | Key informant interviews | Health system providers from health directorates, humanitarian NGOs, donors, and service-users | Opposition-controlled provinces (Aleppo, Dara’a, Hama, Idlib, Rural Damascus) | Chevening Scholarships |

| Duclos (2019) [78] |

First: UK Last: UK |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines cross-border humanitarian assistance and the challenges encountered by humanitarian health actors delivering health care in North-West Syria (Turkish border) | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs; health system (service provision) | September 2017 | Mixed methods, including key informant interviews, desk reviews and expert consultations | Humanitarian aid professionals in Turkey-based organizations operating in North-West Syria, WHO-Turkey staff members and members of Syrian health directorates. | North-West Syria | London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, and the International Development Research Center (IDRC) |

| Falb (2019) [79] |

First: USA Last: USA |

First: humanitarian Last: humanitarian |

Examines associations between depressive symptoms and their potential risk factors (including stressors, intimate partner violence) | Health status; health determinants and risks | March–April 2018 | Cross-sectional survey | Married women who participated in a cash transfer program | Al-Raqqa | UK Department for International Development (DFID) |

| Fardousi (2019) [80] |

First: Lebanon, UK Last: UK, Singapore |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines perspectives of healthcare workers on issues of safety, resource management and handling of mass casualties during siege | Health system (workforce, service provision); war strategies / alleged IHL violations | Not stated | Key informant interviews | Syrian healthcare workers and service users who experienced siege in Aleppo in 2016 or Ghouta (Rural Damascus) in 2013–2017 | Aleppo, Rural Damascus | Chevening Scholarships |

| Fradejas-Garcia (2019) [81] |

First: Spain Last: N/A |

First: academic | Explores experiences of remote cross-border operations | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs | Not reported | Ethnographic study through interviews | Aid workers and organizations – UN agencies, international NGOs and Syrian NGOs – providing relief assistance to Syria remotely | Turkish border city of Gaziantep | Not reported |

| Hallak (2019) [82] |

First: Turkey Last: Turkey |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines optimal shelter locations for IDPs | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs | December 2017–February 2018 | Needs assessment using focus group discussions, key informant interviews and questionnaire with direct beneficiaries; mathematical modelling | Direct beneficiaries in 26 sub-districts within Idlib | Idlib | Not reported |

| Hamid (2019) [83] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Compares dental and gingival status among children with and without PTSD | Health status | Not reported | Case control study | Children (9–14 years old) who attended psychiatry department (cases) or dental service (controls) | Damascus | Damascus University |

| Hamzeh (2019) [84] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First:, academic Last: academic |

Assesses knowledge and awareness of diabetes mellitus and its complications and effects of the conflict on care-seeking behavior among diabetes patients in Damascus | Health status; health determinants and risks | August–November 2017 | Questionnaire | Diabetes mellitus patients attending clinics at the four main hospitals in Damascus | Damascus | Not funded |

| Jamal (2019) [85]e |

First: UK Last: Lebanon |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines the UNRWA health system and factors contributing to its resilience and enabling ongoing delivery of services to Palestinian refugees inside Syria during the crisis | Health system (service provision, governance, medical products, workforce) | February–August 2017 | Key informant interviews, group model building sessions | UNRWA clinical and administrative professionals engaged in health service delivery for Palestinian refugees in Syria over the course of the conflict | Damascus, Jaramana (Rural Damascus), City Center Polyclinicf and Aleppo | Wellcome Trust |

| Mic (2019) [86] |

First: Turkey Last: Turkey |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines optimal locations for primary health care centers in Idlib to allow services to the greatest number of people | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs | March–May 2018 | Needs assessment using focus group discussions, key informant interviews and questionnaire with direct beneficiaries; mathematical modelling | Direct beneficiaries in 23 sub-districts within Idlib | Idlib | Çukurova University (Adana, Turkey) |

| Mohammad (2019) [87] |

First: Syria Last: USA |

First: academic Last: academic |

Evaluates effectiveness of personalized supervision of residents on improving prescribing for asthma management, and effectiveness of mobile video training for inhaler technique | Health system (service provision) | April–May 2018 | Clinical audits; evaluation of efficacy of video-mobile education | Asthma patients at internal medicine clinic in public hospital in Damascus | Damascus | Not reported |

| Muhjazi (2019) [88] |

First: Egypt Last: UK |

First: UN agency Last: humanitarian |

Reports cutaneous leishmaniasis epidemiology over the course of the war | Health status; Health system (information system) | 2007–2010, 2011–2018 | Secondary data analysis of 1) MOH routine surveillance system, 2) EWARS, 3) MENTOR Initiative data | General population | National | Not funded |

| Okeeffe (2019) [89] |

First: Syria Last: Netherlands |

First: humanitarian Last: humanitarian |

Describes blast-wound cases admitted to an MSF supported district hospital during the Raqqa military offensive and the first months of the post offensive period. | Health status; Health system (service provision); humanitarian assessment, response, and needs | June 2017–March 2018 | Retrospective chart review | New blast-wound injured cases admitted to MSF-district hospital in Al-Raqqa in the offensive (June–October 2017) or post offensive period (October 2017–March 2018) | Al-Raqqa | Not funded |

| Ri (2019) [90] |

First: USA Last: USA |

First: academic Last: academic |

Compares trends of attacks on healthcare and civilian casualites to assess feasibility of using publicly available data on attacks on healthcare facilities to describe population-level violence | Mortality; War strategies / alleged IHL violations | March 2011–November 2017 | Secondary analysis of publicly available data from: VDC (civilian casualties), PHR (attacks on healthcare facilities), UNHCR (registered Syrian refugees) | Civilians | National | Not funded |

| Roumieh (2019) [91] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

First: academic Last: academic |

Assesses prevalence of postpartum depression among Syrian women in Damascus and examines associated risk factors | Health status; Health determinants and risks | January–December 2017 | Cross-sectional questionnaire | Postpartum women attending 8 primary healthcare centers in Damascus | Damascus | Damascus University |

| Terkawi (2019) [92] |

First: USA, Saudi Arabia Last: Saudi Arabia |

First: humanitarian, academic, clinical, thinktank/ research organization Last: academic |

Assesses disease burden and clinical presentations of children and adolescents attending a healthcare center in Atmeh district, Idlib | Health status | February–December 2017 | Clinical data analysis | Children and adolescents attending healthcare center in Atmeh district | Idlib | Not funded |

| Terkawi (2019) [93] |

First: USA, Saudi Arabia Last: Saudi Arabia |

First: humanitarian, academic, clinical, thinktank/ research organization Last: academic |

Examines health status and barriers to accessing antenatal care among pregnant women in Northwestern Syria | Health system (service provision); health status; health determinants and risks | February–December 2017 | Medical record review; cross-sectional survey | Pregnant women attending healthcare centers in Atmeh district for antenatal care | Idlib | Not funded |

| Vernier (2019) [94] |

First: Syria Last: UK |

First: humanitarian Last: humanitarian |

Assesses health status and mortality among IDPs who recently arrived to Ein Issa camp in Al-Raqqa | Health status; mortality; humanitarian assessment, response or needs; health determinants and risks | November 2017 | Cross-sectional survey | IDPs who had arrived at Ein Issa camp since October 2017 | Al-Raqqa | MSF |

| Youssef (2019) [95] |

First: Syria Last: Lebanon |

First: academic Last: academic |

Examines the epidemiology of visceral and cutaneous leishmaniases in Lattakia prior to and during the conflict | Health status | 2008–2016 | Registry data analysis | General population | Lattakia | The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) assisted with the publication expenses |

| Ziveri (2019) [96] |

First: Belgium Last: Belgium |

First: humanitarian Last: independent |

Examines impact of a psychosocial support program on the well-being and agency of Syrian farmers receiving livelihood support | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs | April–August 2017 | Randomized control trial among Syrian farmers | Farming households from ten randomly selected villages who fulfilled inclusion criteria | Not reported | Not funded |

aThe other governorates are not specified

b UOSSM Union of Medical Care and Relief Organizations

c Violation Documentation Centre (VDC), Syrian Center for Statistics and Research (CSR-SY), Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), and Syria Shuhada website (SS)

d Unfunded, the study was self-funded. This research was supported by Damascus University

e first published online in 2019, hence captured in this dataset

f The governorate is not specified

Health status is the most frequently researched theme, examined in 38 research papers covering nutrition [10, 94], communicable diseases and/or vaccination status [8, 18, 23, 26, 28, 30, 38, 41, 47, 54, 61, 88, 94, 95], mental health [20, 27, 39, 55, 56, 60, 79, 83, 91, 94], child [22, 41, 57, 92] and maternal [93] health, oral health [44, 72, 75, 83], gender-based violence [76], anaemia [43] and non-communicable diseases [39, 84, 94]. Of studies examining injuries, three are studies of hospital patients [29, 46, 89], one examines injury burden among children surveyed at home and in camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs) [41] and one reports injury counts among children and the general population as provided by key informants [32]. One additional study reports reasons for patient encounters at health facilities [28].

Of these health status studies, a few also report on socioeconomic associations with disease burden [43, 72, 79, 91], health seeking behaviours [84, 93] and exposure to violence as a determinant of health [94]. Several other papers focus primarily on health determinants and risks, including neighbourhood socioeconomic status [9, 68], occupational stress [59], food security [34], and smoking prevalence and smoking behaviours before and during the war [53].

Thirty-four research papers examine the various pillars of the health system. Research on health workforce includes studies of the prevalence of psychological symptoms and burnout among medical students and trainees [27, 71], workforce training [42], interventions using social media platforms as a teaching medium [12], consideration of the impact of conflict on workforce size, support or wellbeing [17, 25, 40, 49, 80, 85], including numbers of health workers killed or injured by attacks on health care [35, 36, 52], workforce wellbeing interventions [59], workforce requirements to address estimates of likely disease burden [20], and studies of medical student career plans [63] and attitudes to research [66].

Health information systems are studied largely in the context of communicable disease surveillance and comparison of surveillance systems covering government and non-government controlled areas [18, 23, 26, 88]. Two papers cover issues of health system governance, one through key informant interviews with health service providers, donors and end-users in opposition-controlled areas [77] and the other through interviews with UNRWA personnel that included consideration of adaptive mechanisms used to ensure resilience and ongoing function of the UNRWA health system [85]. Medical products are the focus of two papers, one of which surveyed community pharmacists in Damascus and Damascus countryside (Rural Damascus) regarding prescription drug misuse and characteristics of patients seeking such medications [70], and the other considered impacts of conflict on the UNRWA system, including on availability of medicines and medical supplies [85]. There are no studies on health financing.

Twenty-one papers cover issues of service provision including renal [17], mental health [20, 24, 56], orthopaedic [73], cancer [40], communicable disease surveillance [54], respiratory [87], antenatal [93], and trauma services [25, 74, 89], disruptions to service provision due to attacks on healthcare [35, 36, 49, 52, 67], challenges of service provision under siege [58, 80], factors enabling sustained UNRWA service delivery [85], and interplays of local service provision with cross-border humanitarian assistance [78].

Humanitarian assistance, response or needs (which included any studies conducted or analysis of services provided by humanitarian agencies) are the focus of 26 papers. These include estimates of IDP numbers and trends [14], humanitarian needs assessments among the general population, many of whom were displaced, in nine predominantly government-controlled governorates in 2014 [13, 14] and among the general population [48] and displaced and female-headed households in 10 largely urban government-controlled areas in 2016 [33]; identifying optimal locations for IDP shelters [82] and primary healthcare facilities [86] in Idlib based on beneficiary needs assessments and modelling; and a snapshot survey of community income and humanitarian assistance in Idlib [31]. Other studies included analysis of Qatar Red Crescent surveys of the impacts of the conflict on education, family and public health status [22] and diagnoses, injuries and comorbidities [41] among children in Northern Syria in 2015; and household surveys of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and health outcomes in opposition-controlled Daraa and Quneitra in 2016–17 [65]. Review of humanitarian programmatic data and operations included middle-upper arm circumference screening, survey of living conditions and food security, and nutritional programming administered by Medecins Sans Frontiers (MSF) in Al-Raqqa in 2013 [10], MSF vaccine-preventable disease risk assessment, pre- and post-vaccine coverage surveys and immunization activity in Aleppo in 2015 [47], 2012–2014 surgical data from an MSF field hospital in Northwest Syria [19], blast injuries managed at an MSF-supported facility in Raqqa in 2017–18 [89], MSF paediatric consultations in Aleppo and Raqqa in 2013–16 [57], MSF assessment of health status of recently arrived IDPs in Al-Raqqa in 2017 [94], primary care services delivered by 10 Union of Medical Care and Relief Organisations (UOSSM) centres in opposition-controlled territories in 2014–2015 [28], and analysis of data from the humanitarian health response in contested and opposition-controlled areas in 2013–14 [32]. Additional interventions and program evaluations included delivery and evaluation of an intervention through provision of information and follow-up questionnaire in bread packages being distributed by a humanitarian organization in Northern Syria [21], evaluation of three modes of food assistance programming in Idlib in 2014–15 [34], evaluation of an International Rescue Committee cash assistance program on violence against women in Raqqa [76], evaluation of effectiveness of multi-level WASH risk reduction interventions in southern Syria in 2018 [64] and examination of the impact of a psychosocial support program on the wellbeing of a control and intervention group of farmers [96]. Several papers interviewed humanitarian workers, including humanitarian health staff working on non-communicable disease (NCD) care in Syria [50] and those involved in the cross-border humanitarian response from Turkey [78, 81].

Fourteen papers research health issues related to war strategies and alleged IHL violations, including an expert panel review of YouTube videos following a sarin gas attack [11] and interviews with healthcare workers in opposition-controlled areas regarding attacks on healthcare and challenges and experiences in responding to chemical attacks [49]. Other research in this theme examined attacks on health care [35, 36, 52, 67, 90], areas under or the effects of siege [40, 58, 80], and war-related mortality [15, 45, 51, 90] including a study of characteristics of deceased victims of a chemical weapons attack [62].

Mortality is the subject of ten papers, which report mortality counts provided by key informants in contested and opposition areas [32]; examine mortality data documented by the Violations Documentation Centre (VDC) [15, 51, 62]), examine associations between attacks on healthcare and civilian casualties [90] or confirm conflict events against war-related deaths from VDC in a fake-news dataset [69]; use capture-recapture methods on four datasets to estimate mortality in two governorates [16]; estimate the number of unique identifiable deaths by deduplicating four datasets [45]; use spatio-temporal death data to forecast conflict events [37] and report on a household survey of IDPs in Raqqa and retrospective one-year mortality, largely conflict-related deaths [94].

Research themes by governorate

Themes studied vary by governorate (Table 1, Fig. 1). In Damascus, health status and the health system are the most frequently studied themes (n = 14 for each). The health system was also the main theme examined in studies of Aleppo (n = 12) and Idlib (n = 9). Humanitarian assistance, response or needs are most frequently studied in the north-west of Syria, including Aleppo (n = 8), Idlib (n = 7) and Lattakia (n = 7), and of the studies examining specific governorates, all 14 governorates were covered in at least one paper. Of the papers examining war strategies and alleged IHL violations, the majority include a focus on Aleppo (n = 6) or Damascus (n = 5). On the national level, the health system is the most frequently studied theme (n = 8), followed by health status (n = 6), war strategies and alleged IHL violations (n = 4) and mortality (n = 3).

Research themes by author country of affiliation

Themes examined vary by country of affiliation of authors (Table 1). Authors with Syrian affiliations commonly publish on health status (n = 21 for first authors, n = 15 for last authors), the health system (n = 12 for first authors, n = 7 for last authors), and health determinants and risks (n = 6 for first authors, n = 5 for last authors), while the most frequently researched themes among US-affiliated authors are the health system (n = 11 for first authors, n = 10 for last authors), humanitarian assistance, response or needs (n = 9 for first authors, n = 3 for last authors), health status (n = 8 for first authors, n = 3 for last authors) and war strategies and alleged IHL violations (n = 6 for first authors, n = 8 for last authors).

Field and operational activities publications

Table 3 presents a summary of the 31 papers reporting on field and operational activities, of which 12 describe humanitarian assessment, responses or needs, including development of a rapid gender analysis tool [127], cross-border, sectoral and cluster coordination mechanisms [104, 115–117], and needs assessments and/or operational programming [98, 105, 107–110, 122]. Nineteen papers discuss various aspects of the health system, most commonly reporting on experiences of establishing and / or presentations to field hospitals [99–101, 103], or establishing or delivering specific services including renal [102, 112], dental [106], mental health [113], obstetric [111], maternal and child health [119], tele-cardiology [120], tele-intensive care [114, 121], tele-radiology [118, 123] and polio outbreak response activities [124]. Other papers described the national tuberculosis control program [125], activities of Syrian expatriate medical associations in supporting the health system, including through training, establishment of hospitals and provision of telemedicine services [97], and translation and uptake of an online medical education platform into Arabic by Syrian medical students [126]. War strategies and alleged IHL violations are the secondary theme of two papers, one describing experiences in besieged settings [123] and one paper reporting birth outcomes by chemical weapons exposure status for pregnant women seen at Al Ghouta hospital in late 2014 [111]. Only 12 (39%) of these field and operational activities publications are first-authored by an author with a Syrian affiliation. Of the 21 publications with multiple authors, only 5 (24%) had a senior (last) author with a Syrian affiliation.

Table 3.

Summary of conflict-related operational and organisational field experience publications, Syria January 2011–December 2019

| First author, publication year | First & last (senior) authors’ country of institutional affiliation | Description | Theme (subtheme)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hallam (2013) [97] |

First: UK Last: N/A |

Lists some activities undertaken by Syrian expatriate medical associations, including provision of training, telemedicine consultations and establishment of hospitals | Health system (service provision, workforce) |

| Harrison (2013) [98] |

First: Syria Last: Switzerland |

Describes UNHCR’s mental health and psychosocial support program | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs |

| Hasanin (2013) [99] |

First: Egypt Last: Egypt |

Describes experiences establishing a field hospital in a district in Aleppo. | Health system (service provision) |

| Sankari (2013) [100] |

First: USA Last: USA |

Describes establishment and activities of field hospitals in Syria | Health system (service provision) |

| Alahdab (2014) [101] |

First: Syria Last: USA |

Describes the experience of field hospitals in Syria | Health system (service provision) |

| Al-Makki (2014) [102] |

First: USA Last: USA |

Describes experiences of provision of renal services and reports on establishment of the Syrian National Kidney Foundation by two Syrian American nephrologists | Health system (service provision) |

| Attar (2014) [103] |

First: USA Last: N/A |

Reports number and type of presentations to four field hospitals in Aleppo during a two week period in December 2013 | Health system (service provision) |

| Dolan (2014) [104] |

First: Not mentioned Last: N/A |

Describes the cross-border nutrition coordination experience in southern Turkey | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs |

| Egendal (2014) [105] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

Describes the World Food Programme’s emergency programme in Syria | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs |

| Joury (2014) [106] |

First: Syria Last: N/A |

Describes a Syrian community-based outreach dental education project named “Syrian Smiles” that aimed to provide dental care services and improve knowledge, skills and attitudes of dental students | Health system (workforce, service provision) |

| Khudari (2014) [107] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

Describes WHO’s nutrition activities in Syria | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs |

| Kingori (2014) [108] |

First: Jordan Last: Syria |

Describes the nutrition crisis response in Syria and UNICEF’s nutrition activities | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs |

| Littledike (2014) [109] |

First: Syria Last: Not clear |

Describes World Vision International’s experiences supporting nutrition and primary healthcare programming to IDPs in Aleppo in 2013–2014 | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs |

| Reed (2014) [110] |

First: Syria Last: N/A |

Describes needs assessment and food and voucher assistance program implemented by GOAL in northern Syria | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs |

| Hakeem (2015) [111] |

First: Syria Last: Syria |

Reviews medical records of 211 pregnant women seen at Al Ghouta hospital in Sept-Nov 2014 (following August 2013 chemical attack) and reports birth outcomes by self-reported chemical exposure status | Health system (service provision); health status; war strategies / alleged IHL violations |

| Saeed (2015) [112] |

First: Syria Last: N/A |

Describes the number of renal transplant centers in Syria, their staffing and activity during the war | Health system (service provision) |

| Jefee-Bahloul (2016) [113] |

First: USA Last: Turkey |

Describes development and application of a tele-mental health system | Health system (service provision) |

| Moughrabieh (2016) [114] |

First: USA Last: USA |

Describes a remote tele-intensive care service and training of supporting staff in Syria | Health system (service provision) |

| Abdulahi (2017) [115] |

First: Syria Last: N/A |

Describes Nutrition Sector co-ordination mechanisms implemented in Syria since 2013 | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs |

| Abdullah (2017) [116] |

First: Syria Last: Jordan |

Describes the Whole of Syria Nutrition Coordination mechanisms implemented in 2015 | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs |

| Madanİ (2017) [117] |

First: Turkey Last: N/A |

Describes the nutrition response in Syria including activities of the Nutrition Cluster | Humanitarian assessment, response or needs |

| Mohammad (2017) [118] |

First: Saudi Arabia Last: Syria |