Abstract

Background

We aimed to externally validate for the first time the diagnostic ability of fibrinogen to identify active inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Methods

The research totally involved 788 patients with IBD, consisted of 245 ulcerative colitis (UC) and 543 Crohn’ s disease (CD). The Mayo score and Crohn disease activity index (CDAI) assessed disease activity of UC and CD respectively. The independent association between fibrinogen and disease activity of patients with UC or CD was investigated by multivariate logistic regression analyses. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) assessed the performance of various biomarkers in discriminating disease states.

Results

The fibrinogen levels in active patients with IBD significantly increased compared with those in remission stage (P < 0.001). Fibrinogen was an independent predictor to distinguish disease activity of UC (odds ratio: 2.247, 95% confidence interval: 1.428–3.537, P < 0.001) and CD (odds ratio: 2.124, 95% confidence interval: 1.433–3.148, P < 0.001). Fibrinogen was positively correlated with the Mayo score (r = 0.529, P < 0.001) and CDAI (r = 0.625, P < 0.001). Fibrinogen had a high discriminative capacity for both active UC (AUROC: 0.806, 95% confidence interval: 0.751–0.861) and CD (AUROC: 0.869, 95% confidence interval: 0.839–0.899). The optimum cut-off values of fibrinogen 3.22 was 70% sensitive and 77% specific for active UC, and 3.87 was 77% sensitive and 81% specific for active CD respectively.

Conclusions

Fibrinogen is a convenient and practical biomarker to identify active IBD.

Keywords: Fibrinogen, Inflammatory bowel disease, Activity

Background

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a chronic recurrent immunologic disease caused by interaction of environmental and genetic factors, become a worldwide health care issue due to its increasingly high incidence and prevalence [1–3]. Crohn’ s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), major types of IBD, appear to result from dysregulation of the immune system [4]. Early detection of disease activity of IBD is conducive to treating the disease timely and preventing the complications effectively so as to improve quality of life and prognosis of patients [5–7]. Endoscopic biopsy remains the golden criterion for assessing and monitoring inflammatory activity of IBD in despite of many efforts to discover new biomarkers [8–10]. However, it has limited use as a result of its invasive nature and the need to collect specimens. Therefore, in order to optimally manage patients with IBD, there is a urgent need for readily obtainable and low-cost markers that enable to evaluate the disease activity of IBD.

In recent years, the lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), which were acquired from the complete blood count (CBC), had been proven to be effective indicators to predict disease activity and severity of IBD [11–14]. Besides, red blood cell distribution width (RDW) had a good ability to evaluate disease activity in CD while RDW performed badly for UC [15]. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were demonstrated to be significant to early diagnose IBD and accurately monitor its disease activity [9, 16, 17]. Inflammation and coagulation were interdependent processes, each activating and propagating the other, which was crucial for the progression of IBD [18, 19]. Distinct pro-inflammatory stimuli activated the clotting cascade, which in turn propagated the inflammatory state by activating signaling pathways, or recruiting more inflammatory cells to the inflamed tissue [19]. Fibrinogen, as factor I in the coagulation process, can also modify multiple aspects of inflammatory cell function by engaging leukocytes through various cellular receptors and mechanisms [20]. However, we discovered that little was known about the value of fibrinogen in identifying IBD in active stage. Therefore, in this study, we elucidated the association of fibrinogen with IBD activity and externally validated the diagnostic ability of fibrinogen to identify active IBD.

Methods

Patients and data

Patients with IBD included were followed up in the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University during the period which began in September 2011 and ended in September 2019. The IBD diagnosis was based on a combination of clinical features, laboratory results, radiological findings, endoscopic findings, and histopathology. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) other immune related diseases, (b) infections, (c) carcinoma, (d) cirrhosis, (e) renal failure, (f) heart failure, (g) respiratory failure, and (h) fibrinogen data lost at admission. According to the criteria above, 788 patients with IBD (245 UC, 543 CD) were included in this retrospective research. Data were extracted from the medical database including epidemiological characteristics such as age, sex, body mass index, and duration of disease; laboratory parameters such as neutrophil, monocyte, lymphocyte, hemoglobin, RDW, platelet, prothrombin time, international normalized ratio, ESR, CRP, and fibrinogen; and endoscopic findings. Duration of disease indicated what moment of the disease the patients were in when recruited, which ranged from 0.5 to 4.0 years in patients with UC and 0.6 to 3.5 years in patients with CD. The CBC parameters were measured including NLR, LMR, and PLR.

Disease activity

The Crohn disease activity index (CDAI) and Mayo score assessed disease activity of CD and UC respectively. Mayo score was a comprehensive scoring system which contained defecation situation, endoscopic results, rectal bleeding, and doctor’s overall evaluation [21, 22]. Patients with UC can be simply and effectively classified by the Mayo score and the score more than 2 indicated that patients with UC were in active stage. The CDAI criteria included body weight, general health condition, hematocrit, abdominal pain severity, daily blood stool count, and complications [23]. The CDAI more than 150 indicated that patients with CD were in active stage.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed median [interquartile range (IQR)], compared by Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were expressed absolute numbers (frequencies), compared by Chi-square test or Fisher’ s exact test. Independent association between biomarkers and disease activity in patients with UC or CD was investigated by multivariate logistic regression analyses to calculate odds ratio with a confidence interval of 95%. The Spearman’ s correlation analysis determined the relationship of biomarkers with the IBD activity. The accuracy of biomarkers in discriminating disease states was evaluated by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC). Calibration of fibrinogen was evaluated by Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit test for significance (P > 0.05). DeLong test compared AUROCs of various biomarkers [24]. The sensitivity and specificity were compared at an optimum cut-off value according to the curve. Patients in UC and CD cohorts were respectively divided into two groups by the optimum cut-off values of fibrinogen. All tests were two sided. P < 0.05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant. STATA (version 14.0; StataCorp, State of Texas, USA) was used for statistics.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 788 patients diagnosed with IBD were included, consisted of 245 (31.1%) with UC and 543 (68.9%) with CD. Table 1 listed characteristics of the subjects we included. Patients in CD cohort was younger than those in UC cohort on the whole. In the UC cohort, the median age was 49 years (37–60 years), and 129 (52.7%) were male, with median disease duration of 1.7 years (0.5–4.0 years). 73 (29.8%) patients were divided into UC remission group while 172 (70.2%) were categorized as UC active group. In the CD cohort, the median age was 27 years (22–33 years), and 396 (72.9%) were male, with median disease duration of 1.8 years (0.6–3.5 years). 257 (47.3%) patients were classified into CD remission group while 286 (52.7%) were categorized as CD active group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the inflammatory bowel disease cohort

| Parameter | UC cohort (N = 245) | CD cohort (N = 543) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49 (37–60) | 27 (22–33) |

| Sex: male | 129 (52.7) | 396 (72.9) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 19.5 (18.4–21.2) | 18.9 (17.4–20.9) |

| Smoking: yes | 39 (15.9) | 84 (15.5) |

| Drinking: yes | 22 (9.0) | 44 (8.1) |

| Duration of disease (years) | 1.7 (0.5–4.0) | 1.8 (0.6–3.5) |

| Endoscopic inflammatory localization of disease | ||

| Proctitis | 45 (18.4) | – |

| Left-side colitis | 107 (43.7) | – |

| Extensive colitis | 93 (38.0) | – |

| Terminal ileitis | – | 130 (23.9) |

| Colitis | – | 107 (19.7) |

| Ileocolitis | – | 306 (56.4) |

| Remission stage | 73 (29.8) | 257 (47.3) |

| Active stage | 172 (70.2) | 286 (52.7) |

Values are expressed as n (%) or median (IQR). UC, ulcerative colitis; CD, Crohn’ s disease; BMI, body mass index

Biomarkers for disease activity

The fibrinogen, CRP, ESR, PLR, and NLR levels in patients with UC in active stage scored significantly higher than those in remission stage, whereas the LMR levels were significantly lower (all P < 0.001) as presented in Table 2. As Table 3 showed, in patients with CD in active stage, the fibrinogen, RDW, CRP, ESR, PLR, and NLR levels were significantly higher while the LMR levels scored significantly lower compared with those in remission stage (all P < 0.001). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that fibrinogen, body mass index, monocyte, and CRP were independent predictors to identify UC in active stage. In addition, fibrinogen, age, sex, body mass index, duration of disease, neutrophil, lymphocyte, hemoglobin, and CRP were independent predictors to identify CD in active stage. More details about multivariate analysis results of disease activity for patients with IBD were presented in Table 4.

Table 2.

Epidemiology and laboratory parameters of ulcerative colitis patients, stratified by disease activity

| Parameter | UC remission (N = 73) | UC active (N = 172) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47 (37–57) | 50 (38–61) | 0.331 |

| Sex: male | 32 (43.8) | 97 (56.4) | 0.072 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.6 (18.8–21.7) | 19.3 (18.3–20.8) | 0.001 |

| Smoking: yes | 10 (13.7) | 29 (16.9) | 0.536 |

| Drinking: yes | 7 (9.6) | 15 (8.7) | 0.828 |

| Duration of disease (years) | 2.0 (0.7–4.3) | 1.1 (0.3–3.8) | 0.042 |

| Neutrophil (109/L) | 3.3 (2.7–4.4) | 4.6 (3.4–7.2) | < 0.001 |

| Monocyte (109/L) | 0.4 (0.4–0.6) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | < 0.001 |

| Lymphocyte (109/L) | 1.7 (1.5–2.2) | 1.8 (1.3–2.2) | 0.428 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.8 (12.0–13.5) | 11.9 (10.4–13.2) | < 0.001 |

| RDW (%) | 13.2 (12.7–13.9) | 13.3 (12.7–14.3) | 0.635 |

| Platelet (109/L) | 235 (201–270) | 281 (214–376) | < 0.001 |

| PT (s) | 13.4 (12.9–13.7) | 13.7 (13.1–14.6) | < 0.001 |

| INR | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 2.7 (2.3–3.2) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | < 0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 3.0 (1.5–3.2) | 12.8 (3.8–32.8) | < 0.001 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 6 (2–15) | 21 (11–37) | < 0.001 |

| NLR | 1.8 (1.3–2.7) | 2.8 (1.9–4.2) | < 0.001 |

| PLR | 130.0 (100.0–174.1) | 166.4 (121.6–222.5) | < 0.001 |

| LMR | 4.2 (3.4–5.1) | 2.7 (1.8–3.5) | < 0.001 |

Values are expressed as n (%) or median (IQR). UC ulcerative colitis; BMI body mass index; Hb hemoglobin; RDW red cell distribution width; PT prothrombin time; INR international normalized ratio; CRP C-reactive protein; ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate; NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR platelet to lymphocyte ratio; LMR lymphocyte to monocyte ratio

Table 3.

Epidemiology and laboratory parameters of Crohn’ s disease patients, stratified by disease activity

| Parameter | CD remission (N = 257) | CD active (N = 286) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27 (22–30) | 26 (22–36) | 0.641 |

| Sex: male | 185 (72.0) | 211 (73.8) | 0.639 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 19.6 (18.3–21.6) | 18.2 (16.4–20.2) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking: yes | 35 (13.6) | 49 (17.1) | 0.258 |

| Drinking: yes | 14 (5.4) | 30 (10.5) | 0.032 |

| Duration of disease (years) | 2.0 (1.0–3.5) | 1.1 (0.3–3.5) | < 0.001 |

| Neutrophil (109/L) | 3.5 (2.7–4.4) | 5.1 (3.5–7.1) | < 0.001 |

| Monocyte (109/L) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | < 0.001 |

| Lymphocyte (109/L) | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | < 0.001 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.5 (12.2–14.7) | 11.5 (10.1–12.6) | < 0.001 |

| RDW (%) | 13.4 (12.7–14.9) | 14.8 (13.3–16.6) | < 0.001 |

| Platelet (109/L) | 246 (206–294) | 328 (254–414) | < 0.001 |

| PT (seconds) | 13.5 (13.1–14.0) | 14.0 (13.3–14.7) | < 0.001 |

| INR | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | < 0.001 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 3.0 (2.4–3.6) | 4.7 (3.9–5.6) | < 0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 3.0 (1.6–8.6) | 30.0 (15.6–60.4) | < 0.001 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 7 (2–14) | 31 (17–48) | < 0.001 |

| NLR | 2.2 (1.6–3.3) | 4.1 (2.8–6.2) | < 0.001 |

| PLR | 168.3 (118.8–231.9) | 264.8 (192.1–370.0) | < 0.001 |

| LMR | 3.0 (2.3–4.2) | 1.9 (1.4–2.6) | < 0.001 |

Values are expressed as n (%) or median (IQR). CD, Crohn’ s disease; BMI body mass index; Hb hemoglobin; RDW red cell distribution width; PT prothrombin time; INR international normalized ratio; CRP C-reactive protein; ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate; NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR platelet to lymphocyte ratio; LMR lymphocyte to monocyte ratio

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis results of disease activity for patients with inflammatory bowel disease

| 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | Lower | Upper | P value | |

| UC | ||||

| BMI | 0.806 | 0.696 | 0.935 | 0.004 |

| Monocyte | 8.848 | 1.662 | 47.111 | 0.011 |

| CRP | 1.099 | 1.035 | 1.168 | 0.002 |

| Fibrinogen | 2.247 | 1.428 | 3.537 | < 0.001 |

| CD | ||||

| Age | 1.059 | 1.026 | 1.092 | < 0.001 |

| Sex: male | 4.975 | 2.254 | 10.981 | < 0.001 |

| BMI | 0.750 | 0.663 | 0.847 | < 0.001 |

| Duration of disease | 0.865 | 0.780 | 0.961 | 0.007 |

| Neutrophil | 1.380 | 1.154 | 1.651 | < 0.001 |

| Lymphocyte | 0.593 | 0.353 | 0.996 | 0.048 |

| Hb | 0.484 | 0.392 | 0.597 | < 0.001 |

| CRP | 1.112 | 1.068 | 1.157 | < 0.001 |

| Fibrinogen | 2.124 | 1.433 | 3.148 | < 0.001 |

ORs and P values were estimated using multivariate logistic regression. Age, sex, and variables were statistically significant in the tests were included in the multivariate analysis. OR odds ratio; CI confidence interval; UC ulcerative colitis; BMI body mass index; CRP C-reactive protein; CD Crohn’s disease; Hb hemoglobin

Correlation of biomarkers and disease activity

Table 5 indicated correlations among biomarkers and disease activity of IBD. Fibrinogen, RDW, ESR, CRP, NLR, and PLR had significantly positive correlations with the Mayo score of UC, whereas LMR was negatively related to the Mayo score of UC (all P < 0.001). Besides, the correlation analysis showed significantly positive correlations of CDAI with the fibrinogen, RDW, ESR, CRP, NLR, and PLR and negative correlations with LMR (all P < 0.001).

Table 5.

Spearman correlation coefficients between biomarkers and disease activity of inflammatory bowel disease

| UC (Mayo score) | CD (CDAI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarkers | r value | P value | r value | P value |

| RDW | 0.147 | 0.022 | 0.361 | < 0.001 |

| ESR | 0.438 | < 0.001 | 0.636 | < 0.001 |

| CRP | 0.599 | < 0.001 | 0.753 | < 0.001 |

| NLR | 0.399 | < 0.001 | 0.444 | < 0.001 |

| PLR | 0.311 | < 0.001 | 0.428 | < 0.001 |

| LMR | − 0.499 | < 0.001 | − 0.452 | < 0.001 |

| Fibrinogen | 0.529 | < 0.001 | 0.625 | < 0.001 |

P and r values were estimated using Spearman correlation analysis. UC ulcerative colitis; CD Crohn’ s disease; CDAI Crohn’ s disease activity index; RDW red cell distribution width; ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP C-reactive protein; NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR platelet to lymphocyte ratio; LMR lymphocyte to monocyte ratio

Diagnostic performance of biomarker

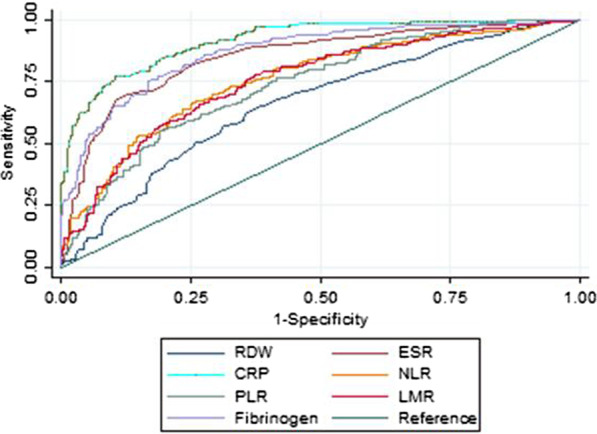

Figures 1 and 2 showed that fibrinogen had higher discriminative capacity for both UC and CD in active stage as compared to RDW, ESR, NLR, PLR, and LMR. CRP performed the best while RDW performed the worst. A fibrinogen cut-off value of 3.22 had a sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 77% for active UC. For active CD, a fibrinogen cut-off value of 3.87 had a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 81%. More details about the performance of various biomarkers were presented in Tables 6 and 7. Fibrinogen had good calibration for disease activity of both UC (P = 0.512) and CD (P = 0.455).

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curves of various biomarkers in identifying active ulcerative colitis. RDW red cell distribution width; ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP C-reactive protein; NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR platelet to lymphocyte ratio; LMR lymphocyte to monocyte ratio

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curves of various biomarkers in identifying active Crohn’s disease. RDW red cell distribution width; ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP C-reactive protein; NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR platelet to lymphocyte ratio; LMR lymphocyte to monocyte ratio

Table 6.

Diagnostic accuracy of various biomarkers in identifying ulcerative colitis in active stage

| Biomarkers | AUROC | 95% CI | P value | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | PV + | PV − | LR + | LR − |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDW | 0.519 | 0.443–0.596 | < 0.001 | 13.7 | 0.40 | 0.71 | 0.77 | 0.34 | 1.39 | 0.84 |

| ESR | 0.764 | 0.701–0.828 | 0.222 | 16.0 | 0.67 | 0.77 | 0.87 | 0.50 | 2.90 | 0.42 |

| CRP | 0.814 | 0.760–0.868 | 0.795 | 3.32 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.60 | 3.21 | 0.28 |

| NLR | 0.683 | 0.611–0.756 | 0.003 | 2.01 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.81 | 0.45 | 1.82 | 0.52 |

| PLR | 0.643 | 0.570–0.716 | < 0.001 | 132 | 0.70 | 0.56 | 0.79 | 0.44 | 1.59 | 0.54 |

| LMR | 0.762 | 0.697–0.826 | 0.282 | 3.59 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.87 | 0.58 | 2.82 | 0.31 |

| Fibrinogen | 0.806 | 0.751–0.861 | Ref | 3.22 | 0.70 | 0.77 | 0.88 | 0.52 | 3.02 | 0.39 |

DeLong test was used to compare the AUROC between fibrinogen and other biomarkers and estimate P values and fibrinogen was the reference. AUROC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CI confidence interval; PV + positive predictive value; PV − negative predictive value; LR + positive likelihood ratio; LR − negative likelihood ratio; RDW red cell distribution width; ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP C-reactive protein; NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR platelet to lymphocyte ratio; LMR lymphocyte to monocyte ratio

Table 7.

Diagnostic accuracy of various biomarkers in identifying Crohn’ s disease in active stage

| Biomarkers | AUROC | 95% CI | P value | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | PV + | PV − | LR + | LR − |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDW | 0.661 | 0.615–0.707 | < 0.001 | 14.0 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.61 | 1.71 | 0.57 |

| ESR | 0.849 | 0.816–0.882 | 0.188 | 21.0 | 0.70 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.72 | 5.45 | 0.35 |

| CRP | 0.916 | 0.893–0.938 | < 0.001 | 14.8 | 0.77 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 7.32 | 0.26 |

| NLR | 0.758 | 0.717–0.798 | < 0.001 | 3.32 | 0.66 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 2.65 | 0.45 |

| PLR | 0.739 | 0.698–0.781 | < 0.001 | 247 | 0.57 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.62 | 2.75 | 0.55 |

| LMR | 0.754 | 0.714–0.795 | < 0.001 | 2.67 | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 2.04 | 0.34 |

| Fibrinogen | 0.869 | 0.839–0.899 | Ref | 3.87 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.76 | 4.12 | 0.28 |

DeLong test was used to compare the AUROC between fibrinogen and other biomarkers and estimate P values and fibrinogen was the reference. AUROC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CI confidence interval; PV + positive predictive value; PV − negative predictive value; LR + positive likelihood ratio; LR − negative likelihood ratio; RDW red cell distribution width; ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP C-reactive protein; NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR platelet to lymphocyte ratio; LMR lymphocyte to monocyte ratio

Groups and outcomes

On the basis of the fibrinogen classification for patients with UC (Group A: < 3.22 and Group B: ≥ 3.22), the active UC patients rates among Group A and B were 47.7% (51/107), and 87.7% (121/138) respectively (P < 0.001). While, on the basis of the fibrinogen classification for patients with CD (Group C: < 3.87 and Group D: ≥ 3.87), the active CD patients rates among Group C and D were 24.0% (66/275), and 82.1% (220/268) respectively (P < 0.001). It is clear that the probability of patients with IBD in active stage significantly increased when fibrinogen was ≥ the optimal cut-off values.

Discussion

Our study externally validated for the first time fibrinogen’ s diagnostic ability to identify patients with IBD in active stage.

It is necessary to timely determine the disease activity of IBD so that we can select optimal treatment and improve the prognosis of patients. Endoscopic biopsy is the golden criterion for assessing and monitoring inflammatory activity of IBD. As for noninvasive biomarker, fecal calprotectin prove to be currently the best biological indicator to discriminate patients with IBD and evaluate disease activity of IBD [25–28]. While, it cannot be widely used in clinical practice due to its high cost, long time requirement, and inconvenience to collect and process samples. Therefore, it is necessary and urgent to search for a simple, accessible and efficient biomarker.

Fibrinogen deposits are a near-universal feature of tissue injury including injury driven by immunological derangements [20]. IBD was an abnormal immune-mediated inflammatory disease of the intestine [2, 4]. Thus, we proposed fibrinogen, a new biomarker to identify patients with IBD in active stage. Our research found fibrinogen levels in patients with IBD in active stage significantly increased compared with those in remission stage. The correlation analysis showed significantly positive correlations of fibrinogen with the Mayo score of UC and the CDAI of CD. Through multivariate analysis to adjust for other parameters, our study further proved fibrinogen was an independent factor to distinguish disease activity of UC and CD. Fibrinogen had higher discriminative capacity for both UC (AUROC: 0.806, 0.751–0.861) and CD (AUROC: 0.869, 0.839–0.899) in active stage compared with RDW, ESR, NLR, PLR, and LMR. Besides, we found CRP performed better than fibrinogen in identifying active IBD. Fibrinogen may be a useful adjunct to or used in conjunction with CRP to quickly and timely identify active IBD. Moreover, we respectively divided patients in UC and CD cohorts into two groups by the optimum cut-off values of fibrinogen. And we found the probability of patients with IBD in active stage significantly increased when fibrinogen was ≥ the optimal cut-off values.

This biomarker has its own unique advantages. First, fibrinogen values can be easily obtained and objectively assessed with an inexpensive and noninvasive blood test. Second, fibrinogen can be used immediately without tedious calculation process. Third, this biomarker has good prediction accuracy and practicality. A fibrinogen more than 3.22 among patients with UC and 3.87 among patients with CD could be an indicator for patients being in active stage. Finally, the fibrinogen classification has some potentially clinical application value in these aspects such as screening of patients with IBD requiring treatment, evaluation of treatment effect, and prediction of IBD complications, which need further study.

However, the study had limitations. First, this research was retrospective and single-center. Besides, some factors were not taken into account such as immunosuppressant and corticosteroids use, which may have influence on the inflammatory marker levels. Finally, part of inflammatory markers were included while others were excluded. We will try to solve these problems in the following research.

Conclusions

Among different biomarkers including fibrinogen, RDW, ESR, CRP, NLR, PLR, and LMR, fibrinogen has a high discriminative capacity for active IBD. Fibrinogen is a convenient and practical biomarker to identify patients with IBD in active stage. Further work is warranted to explore and verify other potentially clinical applications of fibrinogen.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- CD

Crohn’ s disease

- UC

Ulcerative colitis

- LMR

Lymphocyte to monocyte ratio

- PLR

Platelet to lymphocyte ratio

- NLR

Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio

- CBC

Complete blood count

- RDW

Red blood cell distribution width

- ESR

C-reactive protein

- CRP

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- CDAI

Crohn disease activity index

- IQR

Interquartile range

- AUROC

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

Authors’ contributions

Xiao-Fu Chen, Zhi-Ming Huang, and Xie-Lin Huang put forward the research plan; Xiao-Fu Chen, Yuan Zhao, and Yu Guo were involved in data collection and analysis; Xiao-Fu Chen, and Yuan Zhao wrote the manuscript; Zhi-Ming Huang, and Xie-Lin Huang were involved in critical review and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research has received no financial assistance.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and informed consent

The ethics committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University approved this research. The ethics committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University waived informed consent considering the retrospective nature of the study and all the data anonymization. Study was carried out in accordance with ethical guidelines of Wenzhou Medical University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhi-Ming Huang, Email: wyhuangzhiming@126.com.

Xie-Lin Huang, Email: wyhuangxielin@126.com.

References

- 1.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeong DY, Kim S, Son MJ, Son CY, Kim JY, Kronbichler A, et al. Induction and maintenance treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a comprehensive review. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18:439–454. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park JH, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Eisenhut M, Shin JI. IBD immunopathogenesis: a comprehensive review of inflammatory molecules. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:416–426. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, Ardizzone S, Armuzzi A, Barreiro-de Acosta M, et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 1: definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo-anal pouch disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:649–670. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V, Tilg H, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, et al. 3rd European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease 2016: part 1: diagnosis and medical management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:3–25. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walsh AJ, Bryant RV, Travis SP. Current best practice for disease activity assessment in IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:567–579. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faubion WA, Jr, Fletcher JG, O'Byrne S, Feagan BG, de Villiers WJ, Salzberg B, et al. EMerging BiomARKers in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EMBARK) study identifies fecal calprotectin, serum MMP9, and serum IL-22 as a novel combination of biomarkers for Crohn's disease activity: role of cross-sectional imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1891–1900. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis JD. The utility of biomarkers in the diagnosis and therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1817–26.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caviglia GP, Ribaldone DG, Rosso C, Saracco GM, Astegiano M, Pellicano R. Fecal calprotectin: beyond intestinal organic diseases. Panminerva Med. 2018;60:29–34. doi: 10.23736/S0031-0808.18.03405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torun S, Tunc BD, Suvak B, Yildiz H, Tas A, Sayilir A, et al. Assessment of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in ulcerative colitis: a promising marker in predicting disease severity. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao SQ, Huang LD, Dai RJ, Chen DD, Hu WJ, Shan YF. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: a controversial marker in predicting Crohn's disease severity. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:14779–14785. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akpinar MY, Ozin YO, Kaplan M, Ates I, Kalkan IH, Kilic ZMY, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predict mucosal disease severity in ulcerative colitis. J Med Biochem. 2018;37:155–162. doi: 10.1515/jomb-2017-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherfane CE, Gessel L, Cirillo D, Zimmerman MB, Polyak S. Monocytosis and a low lymphocyte to monocyte ratio are effective biomarkers of ulcerative colitis disease activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1769–1775. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeşil A, Senateş E, Bayoğlu IV, Erdem ED, Demirtunç R, Kurdaş Övünç AO. Red cell distribution width: a novel marker of activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Liver. 2011;5:460–467. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2011.5.4.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henriksen M, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, Stray N, Sauar J, Vatn MH, et al. C-reactive protein: a predictive factor and marker of inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Results from a prospective population-based study. Gut. 2008;57:1518–1523. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.146357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon JY, Park SJ, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH, Cheon JH. Correlations of C-reactive protein levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rates with endoscopic activity indices in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:829–837. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2907-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danese S, Papa A, Saibeni S, Repici A, Malesci A, Vecchi M. Inflammation and coagulation in inflammatory bowel disease: the clot thickens. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:174–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owczarek D, Cibor D, Głowacki MK, Rodacki T, Mach T. Inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, pathology and risk factors for hypercoagulability. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:53–63. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luyendyk JP, Schoenecker JG, Flick MJ. The multifaceted role of fibrinogen in tissue injury and inflammation. Blood. 2019;133:511–520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-07-818211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Geboes K, Hanauer SB, Irvine EJ, et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;13:763–786. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, Kern F., Jr Development of a Crohn's disease activity index National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:439–444. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(76)80163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. doi: 10.2307/2531595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosli MH, Zou G, Garg SK, Feagan SG, MacDonald JK, Chande N, et al. C-Reactive protein, fecal calprotectin, and stool lactoferrin for detection of endoscopic activity in symptomatic inflammatory bowel disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:802–19; quiz 820. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Cerrillo E, Moret I, Iborra M, Pamies J, Hervás D, Tortosa L, et al. A nomogram combining fecal calprotectin levels and plasma cytokine profiles for individual prediction of postoperative Crohn's disease recurrence. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:1681–1691. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manceau H, Chicha-Cattoir V, Puy H, Peoc'h K. Fecal calprotectin in inflammatory bowel diseases: update and perspectives. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2017;55:474–483. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2016-0522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daniluk U, Daniluk J, Krasnodebska M, Lotowska JM, Sobaniec-Lotowska ME, Lebensztejn DM. The combination of fecal calprotectin with ESR, CRP and albumin discriminates more accurately children with Crohn's disease. Adv Med Sci. 2019;64:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.