Abstract

Subgenus identification of adenoviruses is of clinical importance and is as informative as identification by serotype in most clinical situations. A PCR-based identification of adenovirus subgenera A, B, C, D, E, and F and sometimes serotypes is described. The PCR uses nonnested primer pair ADRJC1-ADRJC2, which targets a highly conserved region of the adenovirus hexon gene, has a sensitivity of 10 to 40 copies of adenovirus type 2 (Ad2) DNA, and generates 140-bp PCR products from adenovirus serotypes representative of all the subgroups. The PCR products of all subgroups can be differentiated on the basis of the restriction fragment patterns produced by a total of five restriction endonucleases. In addition, serotypes Ad40 and Ad41 (subgroup F) and important serotypes of subgroup D (Ad8, Ad10, Ad19, and Ad37) can easily be differentiated, but serotypes within subgroups B and C cannot. The method was assessed by blind subgenus identification of 56 miscellaneous clinical isolates of adenoviruses. The identities of these isolates at the subgenus level by the PCR correlated 91% (51 of 56) with the results of serotyping by the neutralization test, and 9% (5 of 56) of clinical isolates produced discordant results.

Adenoviruses are double-stranded DNA viruses that are conventionally classified according to serotype (1 to 49) and subgenus (A to F) based upon sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of virion polypeptides and restriction endonuclease (RE) analysis of the whole genome (40). Identification of these subgroups or serotypes can be of both clinical and epidemiological importance (21). Serotypes of subgenus A are isolated almost exclusively from the gastrointestinal tract (34). Adenoviruses of subgroup B, such as adenovirus type 3 (Ad3) and Ad7, and subgroup C (Ad1, Ad2, and Ad5) are common causes of respiratory tract infections (34, 39). Infections with these serotypes may persist asymptomatically for years in children, with the virus being shed continuously in the feces for many months after initial infection and intermittently for years thereafter (15). Certain members of subgroup D (Ad8, Ad19, and Ad37) cause outbreaks of conjunctivitis, and rapid identification of these serotypes can help in prevention and control (14). Subgroup E has one member, Ad4, which can cause either respiratory or eye infection, but a genotype variant of Ad4 (Ad4a) has been associated with outbreaks of conjunctivitis (39). Infantile gastroenteritis is caused by Ad40 and Ad41 (subgenus F) (5). In addition, fatal infections due to certain serotypes, such as those of subgroup B, have been reported (26, 34, 43).

Identification of adenovirus subgroups or serotypes can be achieved, with different degrees of efficiency, by serotype-specific neutralization tests (NTs) (16), RE analysis of DNA extracted from infected cells (40), and, more rarely nowadays, the hemagglutination inhibition test. The results of these methods, although of epidemiological value, are often of limited clinical usefulness. Up to 30 days may be required for complete characterization following the initial isolation of adenovirus in cell culture, which may itself require 30 days or more. In addition, certain adenoviruses such as Ad8, Ad40, and Ad41 are fastidious, with slow and inefficient growth in cell culture (13, 41). Alternative identification methods have therefore been developed and include the use of serotype-specific monoclonal antibodies (1, 42), detection of subgenus-specific antibodies (4), and PCR-based identification protocols (2, 4, 5, 18, 21, 28, 29, 30, 33). In this paper, we describe the development of a simplified, rapid PCR-based method for the identification of human adenoviruses at the subgenus level and, in some cases, the serotype level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Extraction of DNA from virus isolates.

Clinical isolates of Ad types 1 to 12, 14, 16, 19, 21, 31, 37, 40, and 41 typed by NT assay, RE analysis, or type-specific PCR (6, 20) were obtained from the Clinical Virology Laboratory, Manchester Royal Infirmary, Manchester, United Kingdom. DNA was extracted by the guanidinium thiocyanate (GuSCN) procedure described previously (7). Briefly, 200 μl of lysis buffer (4 M GuSCN, 0.5% N-lauroyl sarcosine, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 25 mM sodium citrate, 20 μg of glycogen) was mixed with 50 μl of infected cell culture fluid (or sterile distilled water for an extraction-negative control), and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min, followed by addition of 25 μl of 3 M sodium acetate. The DNA was precipitated with 250 μl of ice-cold isopropanol, and the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded, and 500 μl of cold 70% ethanol was added, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min. Ethanol was gently aspirated, and the pellet was dried in air before it was dissolved in 50 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer.

PCR.

Under strict laboratory practice to avoid cross-contamination and carryover (23), the primer pair ADRJC1-ADRJC2 was used to amplify a 140-bp PCR product as described previously (11). The reaction mixture contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.01% (wt/vol) gelatin, 1.25 U of Amplitaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Ltd., Warrington, United Kingdom), each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 200 μM, 0.2 μM each primer, and 5 μl of appropriate DNA sample or sterile distilled water as a contamination control in a total volume of 50 μl. The reaction was overlaid with 2 drops of mineral oil to prevent evaporation. Amplification was performed on a PHC-1 thermal cycler (Techne Ltd., Cambridge, England) by using one cycle of 94°C for 7 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1.5 min, followed by 40 cycles each of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1.5 min. The PCR products were analyzed with 8% polyacrylamide gels.

RE analysis of PCR products.

The 140-bp PCR products generated from clinical isolates were digested with the REs TaqI, AviII, and AatII (all from Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Lewes, United Kingdom) and BseRI and MnlI (both from New England BioLabs Incorporated, Hitchin, United Kingdom). In a total volume of 20 μl, all reaction mixtures were prepared as recommended by the manufacturers, and those with REs TaqI, AviII, and AatII were incubated for 3 h at the appropriate temperature and those with REs MnlI and BseRI were incubated overnight at the appropriate temperature.

Construction of plasmids and DNA sequencing.

PCR products from Ad2, Ad8, Ad19, and Ad37 were cloned into the PCR-TOPO vector with the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen BV, Leek, The Netherlands) as described by the manufacturer. Recombinant plasmids were purified by the QIAGEN Plasmid Purification Maxi kit (QIAGEN Ltd., West Sussex, United Kingdom) and were sequenced by using the ABI Prism BigDye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (Perkin-Elmer Ltd.) and an automated sequencer (ABI 377; Perkin-Elmer Ltd.). The nucleotide sequences obtained were aligned with sequences in the databases of the National Center for Biotechnology Information by using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool family of programs, and RE analysis was performed with the software WebCutter, version 2.0.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence accession numbers for all the sequences referred to in this paper are given in Fig. 1.

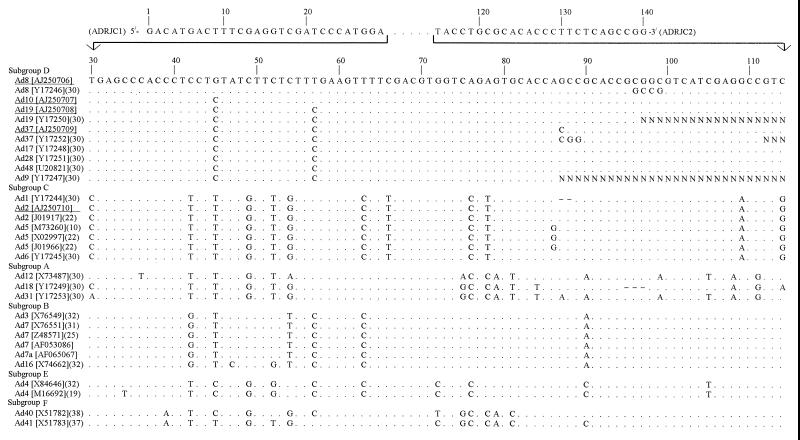

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the nucleotide sequences of the 140-bp PCR products from different adenovirus serotypes. The nucleotide sequences determined in this study are underlined. The sequence accession numbers of all the serotypes are shown in brackets. The nucleotide sequence shown for ADRJC2 represents that of the complementary strand. N, undetermined sequence; −, gaps introduced for alignment of Ad1 and Ad18; periods, identical nucleotides.

RESULTS

Sensitivities and specificities of primers.

The primer pair ADRJC1-ADRJC2 has a detection limit of 10 to 40 copies of Ad2 DNA. The sequences of the upstream primer (ADRJC1) and the downstream primer (ADRJC2) were derived from the highly conserved DNA region which codes for the carboxy end of the monomeric protein II that forms the trimeric pseudohexagonal base of the adenovirus hexon. Both primers contain a maximum of two deliberately introduced mismatches compared with the sequences of the hexon genes of Ad2, Ad3, Ad4, Ad5, Ad7, and Ad16 and a maximum of four mismatches compared with the sequences of the hexon genes of the other serotypes. These mismatches did not involve the 3′ termini of the primers, and the specificity of the test for the detection of representative serotypes from all subgroups was not jeopardized (11).

Comparison of PCR product nucleotide sequences.

The 140-bp nucleotide sequences obtained in this study (Ad2, Ad8, Ad10, Ad19, and Ad37) were aligned with published human adenovirus nucleotide sequences (Fig. 1). Except for Ad1 and Ad18, which showed two and three deletions, respectively, and Ad9, Ad19, and Ad37, for which only partial sequences have been published, all the sequences analyzed were 140 bp in length. Compared with the nucleotide sequence of Ad8 determined in this study, all the sequences demonstrated subgroup-specific patterns and sometimes patterns unique for a serotype.

Construction of identification scheme for adenovirus subgroups A to E.

RE analysis of the nucleotide sequences of the different adenovirus serotypes demonstrated a total of five REs (MnlI, TaqI, BseRI, AatII, and FauI) that were found to be discriminatory, resulting in either subgenus- or sometimes subtype-specific DNA restriction patterns. Based on these patterns, an identification scheme was designed (Fig. 2). The enzyme MnlI divides the analyzed adenovirus sequences into three clusters: subgroup D, subgroups A and C, and subgroups B and E.

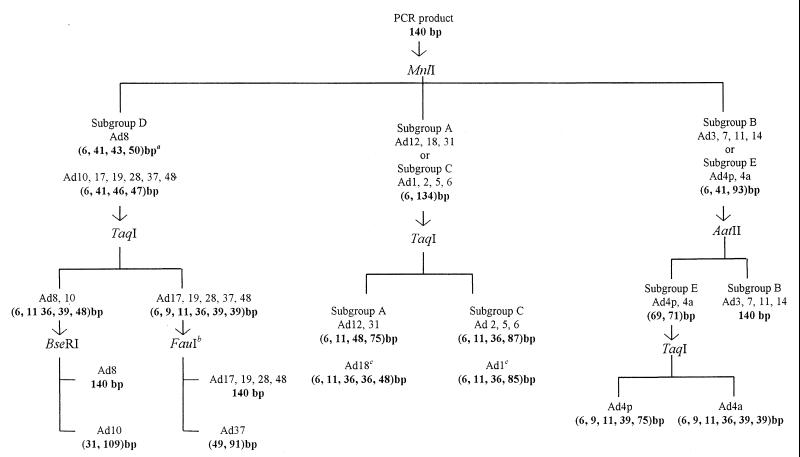

FIG. 2.

Subgenus identification scheme for adenoviruses. PCR products are first treated with MnlI for differentiation into subgroup D, subgroups A and C, or subgroups B and E. TaqI discriminates between subgroups A and C, and AatII differentiates subgroup B from subgroup E. The enzyme TaqI also differentiates Ad8 and Ad10 from the remaining serotypes of subgroup D analyzed. In subgroup E, TaqI produces distinctive patterns for Ad4p and Ad4a. The enzyme BseRI cuts all the analyzed isolates of subgroup D except those of Ad8. The sizes of the DNA fragments generated are given in parentheses. a, Ad10, Ad17, Ad19, Ad28, Ad37, and Ad48 could share this restriction pattern with Ad8 on the basis of RE sequence analysis, but in practice it does not appear to be favored; b, based on RE sequence analysis only (FauI is not commercially available); c, sequence analysis (Fig. 1) shows PCR products of 138 bp (Ad1) and 137 bp (Ad18).

In the first cluster (subgroup D), two patterns of restriction profiles are expected from the sequence information. The first pattern (6, 41, 43, and 50 bp) is possible with all serotypes analyzed (Ad types 8, 10, 19, 37, 17, 28 and 48), but in our experience the pattern was found only with Ad8. The second profile (6, 41, 46, and 47 bp) can be generated only with Ad types 10, 19, 37, 17, 28, and 48 but not Ad8 and is the one that we observed in practice. Further characterization of these serotypes is possible with a maximum of two REs. TaqI differentiates Ad8 and Ad10 from Ad types 19, 37, 17, 28, and 48, and BseRI differentiates Ad8 from Ad10.

In the second cluster, MnlI produces an identical restriction pattern (6 and 134 bp) with serotypes from both subgroups A and C. The two subgroups could then be easily differentiated on the basis of the restriction DNA patterns produced by TaqI. In the third cluster (subgroups B and E), MnlI produces identical DNA restriction patterns (bands of 6, 41, and 93 bp), but AatII provides distinguishable restriction profiles (it produces bands of 69 and 71 bp with subgroup E but does not cut subgroup B).

A total of 33 adenovirus clinical isolates in cell culture fluid were tested by PCR and were identified by following the scheme shown in Fig. 2. The DNA restriction profiles obtained were in complete agreement with the expected patterns.

Blind evaluation of identification scheme.

There can be considerable genetic variability among adenoviruses that have the same antigenic determinants (39). A total of 56 clinical isolates of adenovirus subgroups A to E were amplified, and PCR products were blindly identified by subgenus or sometimes serotype (Fig. 3). Table 1 summarizes the results obtained and their correlation with the results of the NT test and RE analysis. Fifty-one isolates (91%) were correctly assigned to their appropriate subgroup. Those of subgroup A were identified as Ad12 or Ad31; three isolates had been typed by the NT test as type 12 and the remaining two isolates had been typed as Ad31. Among the isolates in subgroup D, based on the assumption that only Ad8, Ad10, Ad19, and Ad37 are included in the blind testing, all 16 isolates were correctly identified, including those of epidemic serotypes Ad8, Ad19, and Ad37.

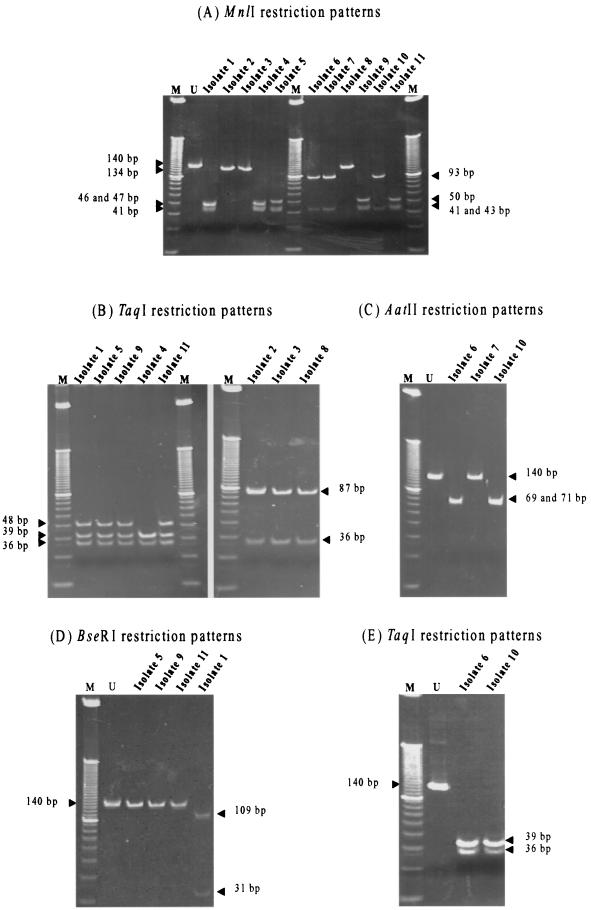

FIG. 3.

Blind evaluation of 11 clinical isolates. PCR products were treated with MnlI (A), TaqI (B and E), AatII (C), and BseRI (D) by following the identification scheme and were separated on 8% polyacrylamide gels. The restriction patterns shown are consistent with Ad8 for isolates 5, 9, and 11, Ad10 for isolate 1, Ad19 or Ad37 for isolate 4, Ad4a for isolates 6 and 10, subgroup C for isolates 2, 3, and 8, and subgroup B for isolate 7. Lanes M, 10-bp DNA ladder; lanes U, uncut PCR product (140 bp).

TABLE 1.

Blind evaluation of the PCR-based identification scheme

| Identity by:

|

No. of isolates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR-based identification scheme

|

Virus neutralization

|

|||

| Subgenus | Serotype | Subgenus | Serotype | |

| Concordant results | ||||

| A | 12 or 31 | A | 12 | 3 |

| 12 or 31 | 31 | 2 | ||

| B | NAa | B | 3 | 7 |

| 7 | 6 | |||

| 11 | 2 | |||

| 16 | 1 | |||

| 21 | 3 | |||

| C | NA | C | 2 | 2 |

| 5 | 2 | |||

| Db | 8 | D | 8 | 7 |

| 10 | 10 | 6 | ||

| 19 or 37 | 37 | 3 | ||

| E | 4a | E | 4 | 7 |

| Discordant results | ||||

| C | NA | A | 31 | 1 |

| B | 14c | 1 | ||

| D | 10 | D | 9 | 1 |

| 10 | B | 7 | 1 | |

| E | 4a | C | 5d | 1 |

| Total | 56 | |||

NA, not applicable.

PCR-based identification is based on the assumption that only Ad8, Ad10, Ad19, and Ad37 are included in the blind testing.

The isolate was typed as Ad34 or Ad35 by RE analysis of the whole genome.

The isolate was identified as Ad2 by RE analysis of the whole genome.

Discordant results were found for five isolates (9%). Of these, two were identified as Ad10, but one had been typed as Ad7 (subgroup B) and the other had been typed as Ad9 (subgroup D) by NT, and two isolates were identified as subgroup C, but one had been typed as Ad31 (subgroup A) and the other had been typed as Ad14 (subgroup B) by NT. The last isolate had also been characterized by RE analysis of the whole genome as Ad34 or Ad35 (subgroup B). The fifth isolate was typed as Ad4a, which is in contrast to the result of Ad5 (subgroup C) by NT and that of Ad2 (subgroup C) by RE analysis.

Identification of adenovirus subgroup F.

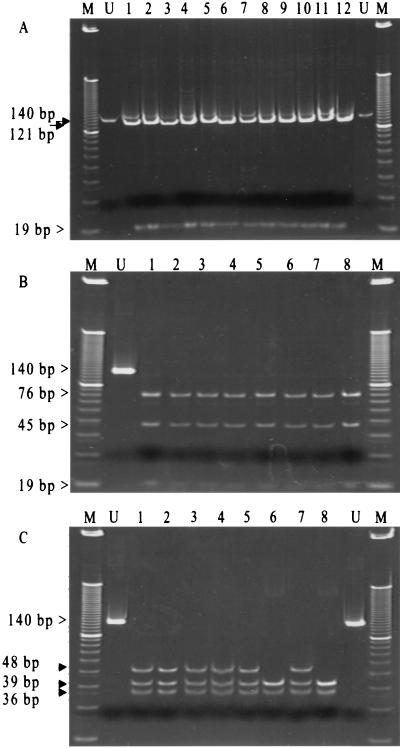

Differentiation of Ad40 and Ad41 (subgroup F) from serotypes of other subgenera in fecal specimens from patients with adenoviral gastroenteritis is of substantial clinical value. Nucleotide sequence analysis of adenovirus subgroup F (Fig. 1) revealed the possibility of including this subgroup in the identification scheme. The nucleotide sequence TGCGCA, located in the upstream primer ADRJC2 at positions 119 to 124, represents a cut site for the enzyme AviII and thus would be shared by all serotypes. However, the same recognition sequence is repeated in Ad40 and Ad41 at positions 74 to 79. This cut site is not present in the analyzed sequences of the other subgroups, leading to a restriction pattern of bands of 19, 45, and 76 bp for Ad40 and Ad41 and bands of 19 and 121 bp for the serotypes from the other subgroups. In addition, Ad40 and Ad41 could be differentiated by TaqI, which produces a DNA restriction pattern with a band of 36 bp and two bands of 39 bp for Ad40 and bands of 36, 39, and 48 bp for Ad41. Evaluation of 8 clinical isolates of subgroup F and 12 isolates of other subgroups (A to E) by RE analysis produced patterns that agreed 100% with the expected RE patterns (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Differentiation and typing of adenovirus subgroup F. PCR products from representative clinical isolates of subgroups A to F were treated with the enzyme AviII (Ad types 8, 10, 2, 5, 3, 7, 11, 14, 21, 4p, 4a, and 31 [lanes 1 to 12, respectively]) (A) and Ad40 and Ad41 (B). (C) TaqI DNA restriction patterns for subgroup F (lanes 1 to 5 and 7, Ad41; lanes 6 and 8, Ad40). Lanes M, 10-bp DNA ladder; lanes U, uncut 140-bp PCR product.

DISCUSSION

Preliminary evaluation of the identification protocol described in this study involved testing of adenovirus serotypes that belong to the different subgroups. In all cases, the predicted restriction patterns were observed on gel electrophoresis. The predicted smaller fragments of 6, 9 and 11 bp could not be observed, and fragments with similar sizes (71 and 69 bp with AatII for subgroup E and 41 and 43 bp or 46 and 47 bp with MnlI for subgroup D) comigrated on the gel, appearing as a single band. These fragments could not be visualized or separated even when a high percentage of polyacrylamide (up to 15%) was used. Smaller fragments may have been denatured into single-stranded DNA, which does not bind to ethidium bromide as efficiently as double-stranded DNA. Alternative procedures such as silver staining, which has been shown to be more sensitive than ethidium bromide in visualizing smaller fragments (9), were not applied in this study. As the small fragments were shared between the subgroups of concern and were mostly generated from cut sites located in primer ADRJC1, they would have no value in identification. In addition, exclusion of attempts to resolve these fragments led to simplified restriction patterns and shorter electrophoresis times, as visualization of smaller fragments may require a higher percentage of polyacrylamide and, thus, longer electrophoresis times for complete separation.

The accuracy and the reproducibility of the test were confirmed by blind evaluation of 56 clinical isolates that had been typed by NT and/or RE analysis of DNA extracted from infected cells. For all but five isolates the test results were in agreement with those of the NT assay (91%) [51 of 56]). This value is similar to that obtained by the study of Kidd et al. (21), in which a PCR-based identification method correlated 91.5% with the results of serotyping by NT. This discordance may be due to misidentification by NT or RE analysis, although the possibility cannot be excluded that the RE profiles of the targeted conserved regions of other adenovirus strains do not match the RE profiles demonstrated in this study and that intermediate strains may be encountered (3, 8, 17, 27).

The protocol developed in this study showed a reliable discriminatory power for adenovirus subgenera and sometimes for adenovirus serotypes and even genotypes. The important epidemic keratoconjunctivitis-causing serotypes of subgroup D (Ad8, Ad19, and Ad37), both serotypes of subgroup F (Ad40 and Ad41), and the genotypes of Ad4 (Ad4p and Ad4a) were easily differentiated, but none of the serotypes within subgroups B or C could be distinguished by this method. Nevertheless, identification of most adenoviruses to the serotype level is often no more useful to the clinician than identification to the subgenus level (21).

Although in our previous study (11) the primer pair ADRJC1-ADRJC2 failed to amplify DNA from Ad40 and Ad41, reevaluation of these primers led to successful amplification of the 140-bp PCR product from clinical isolates of Ad40 and Ad41, and analysis of the published nucleotide sequences of these serotypes revealed that they could be easily distinguished from other serotypes. Thus, for characterization of adenoviruses in fecal samples, the identification scheme could be modified to start first with the enzyme AviII, which places subgroup F in one cluster and the other subgroups (A to E) in another. Characterization of subgroups A to E could then follow by using the scheme in Fig. 2, and typing of Ad40 and Ad41 could be achieved with TaqI.

Several studies have used PCR-based identification systems for subgrouping or subtyping of adenoviruses. Kidd et al. (21) described a PCR-based subgenus identification protocol with primers which bind to regions that flank virus-associated RNA-encoding regions of the adenovirus genome, but the system does not differentiate between adenovirus serotypes of clinical importance, such as Ad8. In the study of Saitoh-Inagawa et al. (33), 14 strains from subgroups A to F were differentiated with a combination of three REs. However, the procedure requires the use of nested primers. Other approaches with PCR-based identification protocols used serotype-specific primers that target serotype-specific regions in the hypervariable or variable domains (2, 28, 29) or that rely on the sequencing of serotype-specific regions (24, 36). Whereas the former approach is prone to possible PCR failure due to variation in the genetic makeup of the target region between strains of the same serotype, the latter can be cumbersome and requires expensive instrumentation.

The PCR-based identification method described here has its own inherent disadvantages. Although most of the REs used were chosen so that their discriminatory power is based on the appearance of different restriction fragments, one enzyme, BseRI, differentiates between Ad8 and Ad10 because it cuts the latter but does not cut the former. This is also true for AatII, which cuts adenoviruses of subgroup E but not those of subgroup B. In such cases, it is difficult to control whether negative results (uncut 140-bp band) indicate the expected adenovirus or merely the failure of the enzyme to cut the PCR product. For BseRI, an additional confirmation is that Ad8 can be differentiated from Ad10 on the basis of RE analysis with MnlI. Unfortunately, in the case of RE analysis with AatII for differentiation of subgroup B and E, no other enzyme can be used to control for its activity. Incomplete cutting by the REs can also cause difficulties. This was most commonly encountered with BseRI and MnlI, but the problem was readily overcome by extending the incubation from 3 h to overnight.

The identification scheme used in the present study appears to be sensitive and simple. The PCR has a detection limit of 10 to 40 copies and is inclusive of all the serotypes tested in this study. The test can be applied to clinical samples, and with a maximum of four restriction enzymes, complete subgenus identification can be achieved within 24 h. For eye swab specimens, only one enzyme (MnlI) is required to exclude or include adenoviruses of subgroup D. With the same enzyme it is possible to include or exclude Ad8. In addition, the test has advantages beyond adenovirus subgenus determination, which should also make it useful for epidemiological surveys. With the exception of subgenera E and F and possibly subgenus D, the subgenus identification of an adenovirus isolate can facilitate serotype identification by NT or serotype-specific PCR. Once the subgroup is identified, serotyping or serotype confirmation can be achieved with a minimum number of neutralizing antisera or by type-specific PCRs. The latter can be combined to include primers for all the serotypes of a subgroup (subgroup-specific multiplex PCR).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam E, Nasz I, Lengyel A. Characterisation of adenovirus hexons by their epitope composition. Arch Virol. 1996;141:1891–1907. doi: 10.1007/BF01718202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adrian T, Pring-Åkerblom P. Molecular epidemiology of human adenoviruses. Biotest Bull. 1997;5:319–323. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adrian T, Bastian B, Benoist W, Hierholzer J C, Wigand R. Characterisation of adenovirus 15 H9 intermediate strains. Intervirology. 1985;23:15–22. doi: 10.1159/000149562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akalu A, Seidel W, Liebermann H, Bauer U, Döhner L. Rapid identification of subgenera of human adenovirus by serological and PCR assays. J Virol Methods. 1998;71:187–196. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(97)00213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allard A, Kajon A, Wadell G. Simple procedure for discrimination and typing of enteric adenoviruses after detection by polymerase chain reaction. J Med Virol. 1994;44:250–257. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890440307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey A S, Richmond S J. Genetic heterogeneity of recent isolates of adenovirus types 3, 4, and 7. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:30–35. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.1.30-35.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behzadbehbahani A, Klapper P E, Vallely P J, Cleator G M. Detection of BK virus in urine by polymerase chain reaction: comparison of DNA extraction methods. J Virol Methods. 1997;67:161–166. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(97)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boursnell M E G, Mautner V. Recombination in adenovirus: crossover sites in intertypic recombinants are located in regions of homology. Virology. 1981;112:198–209. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90625-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown M, Petric M, Middleton P J. Silver staining of DNA restriction fragments for the rapid identification of adenovirus isolates: application during nosocomial outbreaks. J Virol Methods. 1984;9:87–98. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(84)90001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chroboczek J, Bieber F, Jacrot B. The sequence of the genome of adenovirus type 5 and its comparison with the genome of adenovirus type 2. Virology. 1992;186:280–285. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90082-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper R J, Yeo A C, Bailey A S, Tullo A B. Adenovirus polymerase chain reaction assay for rapid diagnosis of conjunctivitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crawford-Miksza L, Schnurr D P. Analysis of 15 adenovirus hexon proteins reveals the location and structure of seven hypervariable regions containing serotype-specific residues. J Virol. 1996;70:1836–1844. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1836-1844.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeJong J C, Wigand R, Kidd A H, Wadell G, Kapsenberg J G, Muzerie C J, Wermenbol A G, Firtzlaff R G. Candidate adenovirus 40 and 41: fastidious adenoviruses from human infant stool. J Med Virol. 1983;11:215–231. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890110305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elnifro E M, Cooper R J, Klapper P E, Bailey A S, Tullo A B. Diagnosis of viral chlamydial keratoconjunctivitis: which laboratory test? Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:622–627. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.5.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox J P, Hall C E, Cooney M K. The Seattle virus watch. VII. Observations on adenovirus infections. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;105:362–386. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hierholzer J C. Adenoviruses. In: Lennette E H, Lennette D A, Lennette E T, editors. Diagnostic procedures for viral, rickettsial, and chlamydial infections. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Public Health Association; 1995. pp. 169–188. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hierholzer J C, Pumarola A. Antigenic characterzation of intermediate adenovirus 14-11 strains associated with upper respiratory illness in a military camp. Infect Immun. 1976;13:354–359. doi: 10.1128/iai.13.2.354-359.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hierholzer J C, Halonen P E, Dahlan P O, Bingham P G, McDonough M M. Detection of adenovirus in clinical specimens by polymerase chain reaction and liquid-phase hybridization quantitated by time-resolved fluorometry. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1886–1891. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.7.1886-1891.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houde A, Weber J M. Sequence of the protease of human subgroup E adenovirus type 4. Gene. 1987;54:51–56. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90346-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussain M A S, Costello P, Morris D J, Bailey A S, Corbitt G, Cooper R J, Tullo A B. Comparison of primer sets for detection of faecal and ocular adenovirus infection using the polymerase chain reaction. J Med Virol. 1996;49:187–194. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199607)49:3<187::AID-JMV5>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kidd A H, Jönsson M, Garwicz D, Kajon A E, Wermenbol A G, Verweij M W, DeJong J C. Rapid subgenus identification of human adenovirus isolates by a general PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:622–627. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.3.622-627.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinloch R, Mackay N, Mautner V. Adenovirus hexon. Sequence comparison of subgroup C serotypes 2 and 5. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:6431–6436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwok S, Higuchi R. Avoiding false positives with PCR. Nature. 1989;339:237–238. doi: 10.1038/339237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Q G, Henningsson A, Juto P, Elgh F, Wadell G. Use of restriction fragment analysis and sequencing of a serotype-specific region to type adenovirus isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:844–847. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.844-847.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Q G, Lindman K, Wadell G. Hydropathic characteristics of adenovirus hexons. Arch Virol. 1997;142:1307–1322. doi: 10.1007/s007050050162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mistchenko A S, Robaldo J F, Rosman F C, Koch E R R, Kajon A E. Fatal adenovirus infection associated with new genome type. J Med Virol. 1998;54:233–236. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199803)54:3<233::aid-jmv15>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noda M, Miyamoto Y, Ikeda Y, Matsuishi T, Ogino T. Intermediate human adenovirus type 22/H10, 19, 37 as a new etiologic agent of conjunctivitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1286–1289. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.7.1286-1289.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pring-Åkerblom P, Adrian T. Type- and group-specific polymerase chain reaction for adenovirus detection. Res Virol. 1994;145:25–35. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2516(07)80004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pring-Åkerblom P, Adrian T, Köstler T. PCR-based detection and typing of human adenoviruses in clinical samples. Res Virol. 1997;148:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2516(97)83992-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pring-Åkerblom P, Trijssenaar F, Adrian T, Hoyer H. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction for subgenus-specific detection of human adenovirus in clinical samples. J Med Virol. 1999;58:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pring-Akerblom P, Trijssenaar F E, Adrian T. Hexon sequence of adenovirus type 7 and comparison with other serotypes of subgenus B. Res Virol. 1995;146:383–388. doi: 10.1016/0923-2516(96)80897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pring-Akerblom P, Trijssenaar F E, Adrian T. Sequence characterization and comparison of human adenovirus subgenus B and E hexons. Virology. 1995;212:232–236. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saitoh-Inagawa W, Oshima A, Aoki K, Itoh N, Isobe K, Uchio E, Ohno S, Nakajima H, Hata K, Hiroaki I. Rapid diagnosis of adenoviral conjunctivitis by PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2113–2116. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2113-2116.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmitz H, Wigand R, Heinrich W. Worldwide epidemiology of human adenovirus infections. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117:455–466. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sprengel J, Schmitz B, Heuss-Neitzel D, Zock C, Doerfler W. Nucleotide sequence of human adenovirus type 12 DNA: comparative functional analysis. J Virol. 1994;68:379–389. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.379-389.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeuchi S, Itoh N, Uchio E, Aoki K, Ohno S. Serotyping of adenoviruses on conjunctival scrapings by PCR and sequence analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1839–1845. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1839-1845.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toogood C I, Hay R T. DNA sequence of the adenovirus type 41 hexon gene and predicted structure of the protein. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:2291–2301. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-9-2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toogood C I, Murali R, Burnett R M, Hay R T. The adenovirus type 40 hexon: sequence, predicted structure and relationship to other adenovirus hexons. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:3203–3214. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-12-3203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wadell G. Molecular epidemiology of human adenoviruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1984;110:191–220. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-46494-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wadell G, Hammarskjöld M L, Winberg G, Varsanyi T W, Sundell G. The genetic variability of adenoviruses. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1980;354:16–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb27955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wigand R. Pitfalls in the identification of adenoviruses. J Virol Methods. 1987;16:161–169. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(87)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wood S R, Sharp I R, Caul E O, Paul I, Bailey A S, Hawkins M, Pugh S, Treharne J, Stevenson S. Rapid detection and serotyping of adenovirus by direct immunofluorescence. J Med Virol. 1997;51:198–201. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199703)51:3<198::aid-jmv9>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zahradnik J M, Spencer M J, Porter D D. Adenovirus infection in the immunocompromised patient. Am J Med. 1980;68:725–732. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]