Abstract

Patient: Male, 39-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Amebiasis

Symptoms: Temperature of 38ºC • abdomial pain and diarrhea

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Critical Care Medicine

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Amebiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. Amebic brain abscesses are a rare form of invasive amebiasis frequently lethal due to the difficulty of its diagnosis and inadequate treatment. Cerebral amebiasis poses a therapeutic challenge as evidenced by the scarcity of papers reporting complete recovering after treatment.

Case Report:

We report the case of a 39-year-old Spanish man, with a history of alcohol and drug abuse. He had never traveled outside of Europe, no reported oral-anal sexual contact, and no history of immunosuppressant medication. He was admitted to the Emergency department with temperature of 38°C, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. An abdominal CT scan showed multiples abscesses in the liver. Therefore, empirical meropenem treatment was started on suspicion of pyogenic liver abscesses due to lack of epidemiological risk factors for parasitic infection. In the liver aspirate samples, E. histolytica trophozoites were directly visualized and a real-time PCR was also positive for it. After amebiasis diagnosis, intravenous (IV) metronidazole therapy was initiated.

During his admission, the patient developed pulmonary, cutaneous and cerebral involvement amebiasis. The management of amebic brain abscesses includes surgical drainage and antiparasitic treatment, in our case IV metronidazole was maintained for 10 weeks. No surgical treatment was performed and even so, the patient evolved favorably.

Conclusions:

Amebic brain abscesses have a high mortality rate if inadequate treatment. A timely diagnosis and suitable treat can reduce its mortality, so the diagnosis of amebic infection should not be precluded in non-endemic countries.

Keywords: Amebiasis, Brain Abscess, Entamoeba histolytica, Metronidazole

Background

Amebiasis is an emerging disease caused by the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica [1–3]. Within the Entamoeba genus, only E. histolytica has been recognized to cause brain abscess. Entamoeba moshkovskii is associated with diarrhea, whereas other Entamoeba species, such as Entamoeba bangladeshi or Entamoeba dispar can be described as nonpathogenic [2,4].

Although amebiasis infection occurs worldwide, autochthonous cases are rare in industrialized countries; and usually observed in migrants and travelers returning from endemic areas, mainly tropical areas and low-income countries with limited socioeconomic resources and poor sanitary conditions. E. histolytica is a prevalent cause of traveler’s diarrhea [4].

The ameba has a two-stage life cycle; the infectious form is the cyst and the invasive form is the trophozoite. Transmission is fecal-oral, generally the result of intake of cysts contained in contaminated water or food, but direct fecal-oral transmission through sexual contact is also described.

Amebiasis can be asymptomatic in about 80–90% of cases or it can lead to the development of severe infection with amebic colitis and amebic liver abscess. Rarely, trophozoites can spread hematogenously to sites outside the gastrointestinal system, such as the central nervous system [3,4].

Brain abscess caused by E. histolytica is an infrequent manifestation of amebiasis infection and is most commonly, although not always, observed in patients with a concomitant liver abscess. Around 133 cases have been reported worldwide [5]. They are very lethal, exhibiting a mortality rate over 95% [6] due to the difficulty of its diagnosis and inadequate management. Treatment of amebic brain abscesses included the combination of surgical drainage and antiparasitic treatment [2]. The way to determine proper treatment is to identify the etiologic agent in time, as delays in its diagnosis may lead to increased mortality.

We describe an unusual case of disseminated amebiasis, in a non-endemic context and the true source of infection remains unclear. The patient presented intestinal amebiasis and extraintestinal spread to liver, peritoneum, lung and brain, as well as skin lesions of amebiasis. Our case is one of the few reported cases in which brain abscesses due to amebiasis have evolved favorably, only with antiparasitic therapy without surgical treatment.

Case Report

Our patient was a 39-year-old Spanish man with a medical history of malnutrition, alcohol and drug abuse, smoking, and pulmonary tuberculosis treated and cured. He came to the Severo Ochoa University Hospital in Leganés, a city southwest of Madrid, Spain. He was admitted to the Emergency Department with temperature of 38°C, abdominal pain, and 7-day diarrhea. He had no recent travel history, had never traveled outside of Europe, had no reported oral-anal sexual contact, and had no history of receiving corticosteroids or immunosuppressant medication.

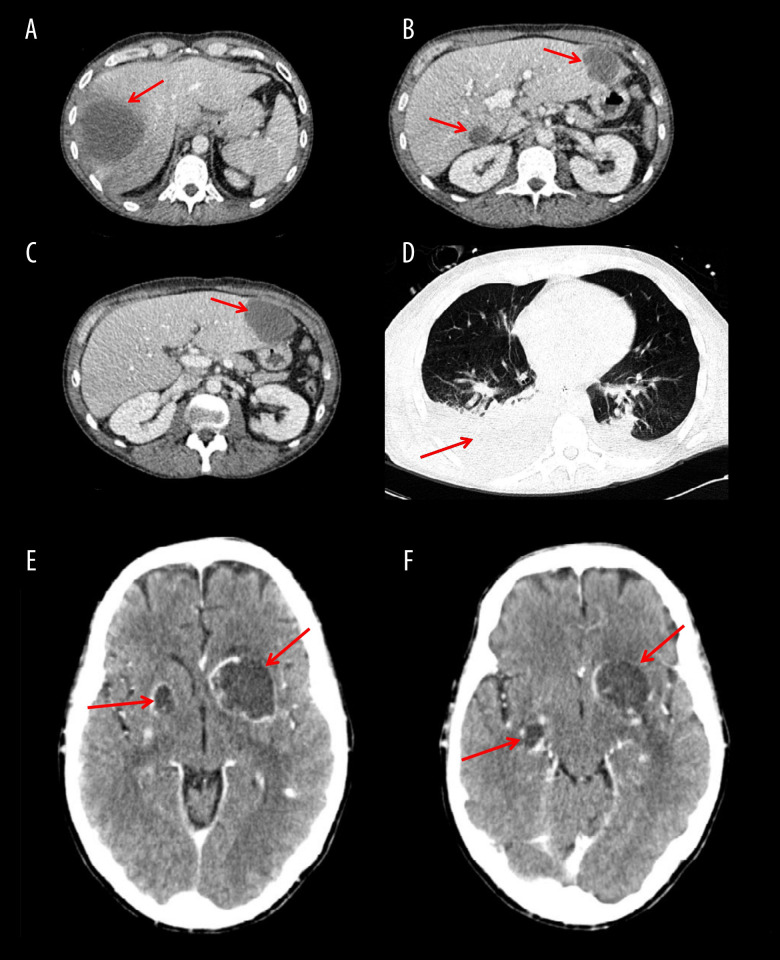

On physical exam, he had tachycardia and tachypnea. Blood laboratory results revealed leucocytosis of 14×109/l (reference range, 4.0–11.0×109/l), raised serum transaminases and inflammatory markers, C-reactive protein level of 308 mg/l (reference range, 0.0–5.0 mg/l) and procalcitonin level of 39 ng/l (reference range, <0.5 ng/l). An abdominal CT scan revealed multiple liver abscesses in the right liver lobe (Figure 1A) and liver segments I and III (Figure 1B, 1C). Empirical antibiotic treatment with i.v. meropenem (1g 3 times daily) was started in the Emergency Department on suspicion of pyogenic liver abscesses due to lack of epidemiologic risk factors for a parasitic infection.

Figure 1.

Thoracoabdominal and cerebral CT scans performed on admission. (A) A 78-mm amebic liver abscess in the right liver lobe. (B, C) Amebic liver abscesses in segments I and III. (D) Amebic pleural effusions and abscess in right lower lobe. (E) Amebic brain abscesses in left basal ganglia and right lenticular nucleus. (F) Amebic brain abscesses in left basal ganglia and right temporal lobe.

In the next hours, the patient had acute clinical deterioration and he was transferred to surgical Intensive Care Unit (ICU). He was endotracheally intubated and mechanical ventilation was started, requiring vasopressor support due to septic shock. Owing to this worsening, it was decided to perform a percutaneous CT-guide drainage of the liver abscesses and micro-biological samples were obtained.

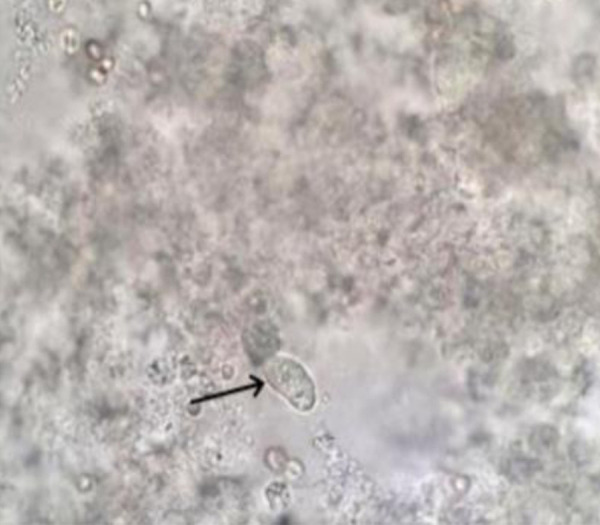

On the 5th day of admission in ICU, liver aspirate revealed a positive visualization on the wet-mount slide of structures of 15–20 µm in diameter, moving by pseudopods, with granular cytoplasm and a single nucleus, compatible with E. histolytica trophozoites (Figure 2). Also, genomic DNA was isolated from this clinical samples using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Extracted and purified DNA samples were stored at 4ºC until molecular processing. Detection of Entamoeba histolytica DNA was performed by real-time PCR (RT-PCT), targeting a sequence of the SSU rRNA gene [7]. The RT-PCR technique allowed the detection of E. histolytica in a sample of liver aspirate. In addition, the stool samples analyzed also showed a positive RT-PCR for E. histolytica. However, bacterial cultures of stool and liver aspirate samples were negative.

Figure 2.

Liver aspirate samples revealed visualization compatible with E. histolytica trophozoites (black arrow).

After the diagnosis of intestinal and extraintestinal amebiasis, i.v. metronidazole 750 mg 3 times daily was added to treat, followed by the luminal agent oral paromomycin, 750 mg 3 times daily (35 mg/kg/day) for 7 days.

Because of respiratory deterioration, a thoracoabdominal CT scan was carried out and it revealed bilateral pleural effusion with an abscess in the right lower pulmonary lobe (Figure 1D) and small disseminated intraabdominal abscesses. On the 10th day of admission, physical exploration, amebic skin lesions appeared on the chest and face.

In addition to feces and liver aspirate samples, bronchial aspirate, pleural drainage, blood, and skin biopsy were analyzed, and RT- PCR for E. histolytica were positive in all samples obtained. HIV serology and PCR for Acanthamoeba spp, Balamuthia mandrillaris, and Naegleria fowleri were negative.

On the 15th day of ICU stay, after he was taken off sedation and mechanical ventilation, the patient presented neurological symptoms with aphasia and right-sided hemiplegia. A cranial CT scan was performed, showing multiple brain abscesses in left basal ganglia and in the right temporal lobe and right lenticular nucleus (Figure 1E, 1F). The Neurosurgery Department was consulted and indicated conservative management; therefore, no brain samples were obtained. The treatment of cerebral amebiasis involved a total of 10 weeks of i.v. metronidazole therapy. Neurological symptoms improved, with full recovery of language, persisting at discharge, and a slight paresis in the right arm.

End-of-treatment CT scans showed residual liver (Figure 3A, 3B) and brain abscesses (Figure 3C–3F).

Figure 3.

Abdominal and cerebral CT scan performed after treatment. (A, B) Residual lesions of liver abscesses after metronidazole therapy. (C) Amebic brain abscesses after 2 weeks of i.v. metronidazole treatment. (D) Amebic brain abscesses after 4 weeks of i.v. metronidazole treatment. (E) Amebic brain abscesses at end of treatment, 10 weeks of i.v. metronidazole treatment. (F) Residual lesions of amebic brain abscesses 6 months after discharge from the surgical ICU.

Despite having various complications during his admission (co-infection of liver abscesses by Staphylococcus epidermidis and Clostridium difficile pseudomembranous colitis), the patient was discharged after a 16-week stay in the surgical ICU. He is currently stable and rehabilitating.

Discussion

Although amebiasis infection can occur worldwide, individuals living in developing countries are at the greatest risk given poor sanitation and socioeconomic conditions. Up to 50 million people are infected with E. histolytica around the world and it is responsible for 40 000 to 100 000 deaths a year [1–4]. In developed countries like Spain, amebiasis infection is seen in migrants and travelers returning from endemic areas, or in high-risk groups, which include people who have oral-anal sexual practices and immunocompromised populations. In developed countries, sexual contact has also emerged as an important risk factor for transmission [7].

E. histolytica is transmissible person-to-person and its transmission may be likely within households. However, at the time of infection our patient did not report having a stable partner, and did not report having oral-anal sexual activity. No serological studies were performed on his family members, as they were not co-habitants. In our patient, we found no apparent epidemiologic risk factors for the acquisition of amebiasis, so the true source of infection could not be established.

Although the majority of amebic infections are asymptomatic, their invasiveness has been related to interactions between the intestinal bacterial microbiota and innate or acquired immune responses. Amebic contact can evoke various host immune mechanisms to prevent infection. Acquired immunity protects against amebic invasion by producing antibodies to the Gal/ GalNAc lectin antigens and against to the EhMIF (proinflamma-tory cytokine macrophage migration inhibitory factor), while the innate immune response protects by releasing neutrophils at the site of invasion [3,4]. Also, the release of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) can confer protection against E. histolytica diarrhea, especially in children [3]. In normal circumstances, these immune responses confer protection; nevertheless, in some cases, the elicited response is excessive and thus deleterious [3].

Host factors such as genetic susceptibility, immune status, young age, pregnancy, corticosteroid therapy, malnutrition, and alcohol abuse have been described as risk factors in the dissemination and severity of amebiasis [4,7]. A sex difference in amoebic infection has also been documented, with more invasive disease in males; for example, over 80% of amebic liver abscesses occur in adult men [7]. Our patient was a young man with a history of alcoholism and malnutrition; these factors probably favored a greater invasiveness of the amebic disease.

Accurate differential diagnosis of parasitic diseases is an emerging health problem [8]. In non-endemic countries, the amebiasis diagnosis is challenging because it relies on unspecific clinical symptoms and laboratory tests with variable sensitivity and specificity. Furthermore, identification of these infections generally requires experienced and qualified personnel [8].

Intestinal amebiasis is diagnosed by microscopic identification of cysts and trophozoites in stool. Cysts and trophozoites (with or without hemophagocytosis) can be visualized by an experienced eye using microscopy, but this test lacks specificity and has low sensitivity [4,8]. Moreover, microscopy cannot accurately differentiate between E. histolytica and species of lesser or no pathogenic potential, such E. dispar or E. moshkovskii, which are morphologically indistinguishable. In extraintestinal amebiasis disease, the microscopic analysis of aspirate samples has low sensitivity (less than 20%) in the identification of trophozoites [2]. A PCR of extraintestinal samples always has to be performed to increase sensitivity and to confirm the species identification [9].

Tests for antigen detection in stool are easy to use and are highly sensitive in endemic areas, but with variable sensitivity in non-endemic areas [7,8]. No specific antigen tests are available for the detection of Entamoeba dispar and Entamoeba moshkovskii from clinical samples [9]. Also, stool antigen detection only has 40% sensitivity for the diagnose of amebic liver abscess. [2].

Serology is both highly sensitive and specific, and is a useful complement to stool studies. As a disadvantage, serology remains positive for a long time after infection, so its use is limited in endemic areas. Antibody detection is most useful to diagnose of amebic liver abscess and other forms of extraintestinal disease, in case the stool studies are negative [9].

Molecular analysis by RT-PCR based assays is the criterion standard for diagnosis of amebiasis, discriminating between Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar [4,7,8]. RT-PCR is the most sensitive method for detecting amebiasis in stool or abscess fluid. In our case, the diagnosis was established by microscopy of the liver abscess sample and was confirmed by RT-PCR of the liver abscess, stool, pleural fluid, and blood and skin biopsy samples.

The liver is the most frequent extraintestinal organ affected by amebiasis, presenting as amebic liver abscess (ALA). It is 7–10 times more likely among adult men with amebic infection [1–3]. Radiology cannot determine the etiology. In developed countries, the differential diagnosis of ALA should include the pyogenic liver abscess, hepatoma, and echinococcal cyst [2,3]. In our case, the absence of travel to endemic areas led us to miss the initial diagnosis of amebiasis.

Complications of ALA include rupture with extension to the peritoneum, pleura, pericardium, and hematological spread. However, routine drainage is not usually required and should be reserved for cases with no response to treatment in the first 72 h or if there is high risk of rupture: diameter >5 cm, less than 1 cm between the abscess wall and the liver surface, or left lobe abscess [1–4]. In our patient, drainage of the abscess allowed a confirmatory diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Pulmonary complications are the second most frequent extraintestinal complication (7–20% of patients with ALA); it can be derived of direct ALA rupture through the diaphragm or hematogenous spread. In general, amebic pleural effusions and abscess can be easily treated with drainage and antimicrobial therapy [10].

The majority of cutaneous amebiasis is described by the contiguous spread in the anogenital region [11]. Our patient developed cutaneous amebiasis, localized on the chest and face (Figure 4A, 4B), without cutaneous involvement in the peri-anal area. Cutaneous amebiasis is extremely rare; the parasite can be transmitted from contiguous spread, contaminated patient`s fingers after scratching, or by parasitemia. We suspect the latter was the most probable underlying mechanism in our patient (RT- PCR was positive in the blood samples, suggesting hematogenous spread).

Figure 4.

Images of cutaneous amebiasis lesions present on chest (A) and face (B).

Amebic brain abscesses are extremely rare and arise almost exclusively alongside amebic lung or liver abscess [2]. Victoria-Hernández et al reported 133 cases worldwide [5], with a mortality rate over 95% [6] due to the difficulty of its diagnosis (CT images of E. histolytica abscesses are indistinguishable from those CT images of abscesses due to other organisms) or due to inadequate treatment, especially if drainage is not performed [5,6,12,13]. In many published cases of cerebral amebiasis, the diagnosis is made postmortem [6]. In the literature, there are few cases of cerebral amebiasis that evolved well despite not receiving surgical treatment [14,15].

Treatment of invasive amebic infection requires the use of an amebicidal tissue-active agent, such as metronidazole or tinidazole, followed by a luminal cysticidal agent like paromomycin or diloxanide, to eradicate colonization. A 5- to 10-day course of therapy is recommended in amebic colitis and a 10-day course in the cases with amebic liver abscess [3]. However, there is no consensus on the duration of the therapy in brain abscesses; up to 8 weeks are described in the literature [12,13].

The approach to amebic brain abscesses includes the combination of surgical drainage and antimicrobial treatment [2]. Owing the paucity of literature on the duration of therapy, a longer treatment period may be warranted [12,13]. In our case, metronidazole was withdrawn after 10 weeks of treatment until a neurological improvement was observed, alongside a reduction of brain lesions in the cranial CT scan. Surprisingly, the patient had a good evolution even in the absence of surgical treatment, contrary to what has been published in the literature.

We report a patient with invasive amebiasis, with amebic cerebral affecting, who responded well to medical therapy. The patient survived with prolonged metronidazole therapy, untreated surgically. Our case is one of the few reported cases in Spain of amebic brain abscess with a good outcome as a result of a timely diagnosis and suitable treatment.

Conclusions

Amebic brain abscess has a high mortality rate if inadequately managed. The possibility of amebic infection should not be ruled out in non-endemic countries; early recognition of invasive amebiasis contributes significantly in reduce its morbidity and mortality. However, the need for surgery or the duration of amebicidal therapy in amebic brain abscess remains a matter of debate. Further investigations will help in the management of this severe disease when cerebral spread is presented.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient and his family for granting permission to publish this information.

Footnotes

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

References:

- 1.Stanley SL., Jr Amoebiasis. Lancet. 2003;361:1025–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12830-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petri WA, Haque R. Entamoeba histolytica brain abscess. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;114:147–52. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53490-3.00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shirley DT, Farr L, Watanabe K, Moonah S. A review of the global burden, new diagnostics, and current therapeutics for amebiasis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(7):ofy161. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantor M, Abrantes A, Estevez A, et al. Entamoeba histolytica: Updates in clinical manifestation, pathogenesis, and vaccine development. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018:4601420. doi: 10.1155/2018/4601420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Victoria-Hernández JA, Ventura-Saucedo A, López-Morones A, et al. Case report: Multiple and atypical amoebic cerebral abscesses resistant to treatment. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:669. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05391-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maldonado-Barrera CA, Campos-Esparza MR, Muñoz-Fernández L, et al. Clinical case of cerebral amebiasis caused by E. histolytica. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:1291–96. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2617-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madden GR, Shirley DA, Townsend G, Moonah S. Case Report: Lower gastrointestinal bleeding due to Entamoeba histolytica detected early by multiplex PCR: Case report and review of the laboratory diagnosis of amebiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;101(6):1380–83. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutiérrez-Cisneros MJ, Cogollos R, López-Vélez R, et al. Application of real-time PCR for the differentiation of Entamoeba histolytica and E. dispar in cist-positive faecal samples from 130 immigrants living in Spain. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2010;104:145–49. doi: 10.1179/136485910X12607012373759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fotedar R, Stark D, Beebe N, et al. Laboratory diagnostic techniques for Entamoeba species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(3):511–32. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00004-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zakaria A, Al-Share B, Al Asad K. Primary pulmonary amoebiasis complicated with multicystic empyema. Case Rep Pulmonol. 2016;2016:8709347. doi: 10.1155/2016/8709347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Daraji WI, Husain EA, Robson A. Primary cutaneous amoebiasis with a fatal outcome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:398–400. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31816bf3c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamer GS, Öncel S, Gökbulut S, Arisoy ES. A rare case of multilocus brain abscess due to Entamoeba histolytica infection in a child. Saudi Med J. 2015;36:356–58. doi: 10.15537/smj.2015.3.10178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solaymani-Mohammadi S, Lam MM, Zunt JR, Petri WA. Entamoeba histolytica encephalitis diagnosed by PCR of cerebrospinal fluid. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:311–13. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lombardo L, Alonso P, Sáenz Arroyo L, et al. Cerebral amoebiasis: Report of 17 cases. J Neurosurg. 1964;21:704–49. doi: 10.3171/jns.1964.21.8.0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamasaki M, Taniguchi A, Nagai M, et al. [Probable amebic brain abscess in a homosexual man with an Entamoeba histolytica liver abscess.] Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2007;47(10):672–75. [in Japanese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]