Summary

German National Recommendations for Physical Activity (PA) and PA Promotion recommend community-based approaches to promote PA at the local level with a focus on health equity. In addition, the German Federal Prevention Act addresses health equity and strengthens setting-based health promotion in communities. However, the implementation of both in the local context remains a challenge. This article describes Phase 1 of the KOMBINE project that aims to co-produce an action-oriented framework for community-based PA promotion focusing on structural change and health equity. (i) In a series of workshops, key stakeholders and researchers discussed facilitators, barriers and needs of community-based PA promotion focusing on health equity. (ii) The research team used an inductive approach to cluster all findings and to identify key components and then (iii) compared the key components with updated literature. (iv) Key components were discussed and incorporated into a gradually co-produced framework by the participants. The first result of the co-production process was a catalog of nine key components regarding PA-related health promotion in German communities. The comparison of key components with scientific evidence showed a high overlap. Finally, a six-phase action-oriented framework including key components for community-based PA promotion was co-produced. The six-phase action-oriented framework integrates practice-based and scientific evidence on PA-related health promotion and health equity. It represents a shared vision for the implementation of National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion in Germany. The extent to which structural changes and health equity can be achieved is currently being investigated in pilot-studies.

Keywords: physical activity promotion, community, recommendations, implementation

Lay Summary

This paper describes how the participants in the KOMBINE project were involved in an innovative approach to transfer the German National Recommendations for Physical Activity (PA) and PA Promotion into the local practice of communities. Scientists, politicians and community actors (e.g. mayors, heads of sports departments) discussed their knowledge and experiences of facilitators, barriers and needs to promote PA in communities, specifically for people in difficult life situations (e.g. individuals with social disadvantages). Based on the results, they jointly developed key components and an action-oriented framework to implement the National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion in German communities.

INTRODUCTION

There is increasing recognition of the importance of health equity issues in public health, but the implementation of programs designed to reduce health inequities remains a major challenge. Usually, structural changes in the provision of preventive and health-promoting services are necessary to promote health equity, and this kind of social change is especially difficult to achieve. This paper outlines an initial step in tackling this implementation challenge in health promotion by activating key stakeholders from different levels (local, state, national) and sectors (e.g. health, sports). It further demonstrates how evidence from research as well as public health practice can be integrated and how an action-oriented framework to overcome implementation challenges can be developed in a transdisciplinary, cooperative manner.

BACKGROUND

The German National Recommendations for Physical Activity (PA) and PA Promotion have been available since 2016 and recommend community-based PA promotion focusing on structural changes aimed at facilitating health equity (Rütten and Pfeifer, 2016; Rütten et al., 2018). Furthermore, the new Federal Prevention Act, launched in 2016, strengthens the role of setting-based health promotion in local German communities. It aims to address structural issues in the provision of preventive and health-promoting services and to reduce health inequities. Based on the Prevention Act (Section 20 Abs. 6 SGB V), health insurances are required to spend around EUR 150 million per year on setting-based health promotion in local communities across Germany (NPK, 2019). Since 2017 the Prevention Act also created the first national and regional structures for the implementation of setting-based health promotion measures. However, both the implementation of the Federal Prevention Act as well as the implementation of the National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion at the local level in communities remain a challenge.

In this regard, the problem of translating evidence into practice has also been reported for other published PA guidelines and their uptake in the ‘real world’ (Cameron et al., 2007; Gainforth et al., 2013). This is influenced by the fact that their implementation at the local level often requires multiple stakeholders from diverse sectors (e.g. health, sports, urban planning) within different types of communities (e.g. rural, urban, metropolis) to change their usual routines and local actions (Leone and Pesce, 2017; Grant and Davis, 2019). Therefore, implementing PA-related health promotion in local communities and to promote structural changes aimed at fostering health equity are complex societal problems for which a transdisciplinary approach is promising (Stokols et al., 2013). This approach (Jahn et al., 2012; Stokols et al., 2013; OECD, 2020) emphasizes both scientific knowledge as well as practice-based knowledge including policy-based knowledge to develop solutions for complex societal problems and to enhance societal impact. The participation of academic researchers as well as non-academic participants is essential to co-produce new knowledge to address such complex problems.

For the first time in Germany, KOMBINE (Community-Based PA Promotion to Implement National Recommendations, 2018–21) has been set up on the national level as a transdisciplinary pilot project to further enhance the implementation of the National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion at the local level of communities in Germany. The National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds (GKV-Spitzenverband), an umbrella organization of health insurance programs, as well as the Federal Centre of Health Education (BZgA), have offered funding for ‘KOMBINE’. It also functions as a pilot project for the nationwide implementation of the new Federal Prevention Act.

KOMBINE is understood as a whole-system approach (Rütten et al., 2019) in the municipal setting to promote PA at the population level. Approaches that target the whole population are generally more likely to reach the well-off parts of the population and thereby can increase health inequity (Frohlich and Potvin, 2008; Lorenc et al., 2013). Hence, KOMBINE considers strategies to reach the whole population and particularly populations with social disadvantages to address health equity issues.

Social disadvantages are understood as substantially reduced chances of population groups to achieve a certain goal due to factors which they cannot influence or change themselves (SVR Gesundheit, 2007). Population groups with social disadvantages are defined as those with very low income, very low social status (e.g. unskilled workers), very low school education or other social disadvantages (e.g. single parents, migrants with poor knowledge of German). Those social disadvantages contribute to health inequities as they reduce the fair opportunity to attain the full health potential (Nutbeam and Muscat, 2021). For Germany data show less self-reported PA in all age groups for individuals in the lower educational group compared with individuals in the higher educational group (Finger et al., 2017). A recent analysis of 13 German cross-sectional data sets confirmed that adults with lower levels of education, higher age, lower income and a migrant background had a higher risk of not engaging in sports, and showed an increased risk of not engaging in vigorous PA (Abu-Omar et al., 2021).

The aim of the present article is to describe Phase 1 of KOMBINE, which incorporates a systematic activation of stakeholders to co-produce an action-oriented framework on the national level for the implementation of community-based PA promotion with a focus on structural change and health equity. Given the transdisciplinary approach of KOMBINE a special focus is put on how to integrate scientific knowledge as reported in the German National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion with practice-based knowledge consisting of experiences and local know-how from various community stakeholders including representatives of population groups, and policymakers as well as multipliers (e.g. professionals in the planning and implementation of health promotion projects). These non-academic participants jointly develop together with the academic research team the action-oriented framework.

In Phase 2 of KOMBINE, the action-oriented framework will be tested in six pilot communities. The active participation of local community stakeholders, local policymakers, representatives of population groups including socially disadvantaged people is crucial for this phase.

The third phase aims on the creation of a manual on the KOMBINE approach. It builds up on the experiences of Phase 2 and includes a step-by-step guidance for interested stakeholders from other communities in Germany (see Supplementary Appendix 8).

METHODS

Over a 5-month period, two workshops with all participants and two additional meetings in each of three working groups were conducted to integrate scientific knowledge gained from the field of PA research with practice-based knowledge from local community stakeholders, multipliers and national policymakers (see Supplementary Appendix 1). Both workshops were held as 1-day events, the first at the beginning and the second at the end of the 5-month period. They consisted of plenary sessions with all participants and were used to form the working groups dependent on community size. Additional meetings of these three working groups took place independent from each other in between the two workshops.

Recruitment and invitation of participants

Based on previous experiences and contacts from the development of the National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion (Abu-Omar et al., 2019), participants were recruited across Germany via the following sampling strategy: (i) mailing lists and newsletters from federal and national organizations in the field of health and PA promotion; (ii) personal invitations of all community leaders (e.g. mayors, county commissioners, heads of sports and health departments) and (iii) through multipliers involved in the development of the German National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion. The aim was to reach community leaders and staff (e.g. from the sports sector, health sector and representatives of population groups with social disadvantages), multipliers and policymakers active in the field of PA-related health promotion for a nationwide exchange.

The KOMBINE team, which consisted of seven academic staff members, participated in both workshops and the additional working group sessions as hosts, co-moderators and presenters. Three additional experts moderated the communication during all meetings to support the desired bottom-up approach. These experts were researchers from other universities in Germany, who were selected based on their expertise, including their experience with community-based PA promotion and their involvement in the former development of the National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion. Throughout the workshops and working groups three student assistants (one student in each of the three working groups) documented the discussions by writing protocols and one student assistant took photos.

Workshop 1 procedure

Workshop 1 aimed (i) to introduce the German National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion for community-based PA promotion with an emphasis on populations with social disadvantages; (ii) to illustrate three examples of good practice for community-based PA promotion (one project from a rural area, one from a medium-sized city and one from a metropolitan area) and (iii) to learn from the practice-based knowledge of the participants. Presentations during the meeting addressed the first two aims and facilitated working group sessions, followed by a panel discussion to achieve the third aim. Prior to the group sessions, the academic staff members of KOMBINE divided the participants into three groups according to the size of their communities: rural areas (communities with <100 000 inhabitants), urban areas (communities with 100 000–500 000 inhabitants) or metropolises (communities with >500 000 inhabitants). The task was the same for each working group namely, to identify the facilitators, barriers and needs of community-based PA promotion regarding population groups with social disadvantages (see Supplementary Appendix 2). Therefore, each working group addressed the following three questions: ‘What works in practice?’, ‘What are the barriers?’ and ‘What needs for action do you see in the promotion of PA?’. Participants were asked to write their answers as notes on blank moderation cards. All moderation cards were collected and discussed within the working groups. Afterwards, an overview of the notes of all three working groups was presented by the moderators and reflected upon in the panel discussion among all workshop participants.

After Workshop 1, two KOMBINE staff members started independently with the step-by-step sorting of the moderation cards with participants’ notes based on their content within each of the three examined criteria (‘facilitators’, ‘barriers’, ‘needs’) for each working group. In case of disagreements, these were resolved through discussions between the two researchers. Subsequently, the same two researchers jointly discussed overarching categories for the clustered notes under ‘facilitators’, ‘barriers’ and ‘needs’ for each working group. Based on these categories they identified key components for the implementation of community-based PA promotion. In the next step, the KOMBINE research team jointly discussed the key components until all agreed. Finally, the key components were subsequently verified in the working groups by the participants.

Working group procedure

Following the first KOMBINE workshop, two additional meetings consisting of four stages were held for all three working groups (rural areas, urban areas, metropolises). In each working group, the first interactive meeting took place in December 2018. The meetings focused on the proof of the key components (Stage 1) and a co-production of an action-oriented framework for community-based PA promotion (Stage 2). Supported by a moderator and a KOMBINE team member, the session started with a presentation of working group results from the first workshop and an in-depth introduction to the identification of the key components to the participants. Accordingly, an overview of the clustered notes was shown for all key components that led to their formation. The participants were given the opportunity to discuss and adjust these key components, if necessary, until everyone agreed with the meaning of the key components. The second part of the meeting focused on mapping the key components to a three-phase framework for action. Consisting of ‘assessment’, ‘planning’ and ‘action’ phases, this framework is based on concepts of participatory approaches (Institute of Medicine, 1988; Ammerman et al., 2014; Leask et al., 2019). As emerged from the discussions in the working groups, the initial three-phase framework model was helpful as a starting point, and it was jointly decided to expand the phases of the framework. Based on the suggestions from participants in the meeting and the KOMBINE staff’s knowledge about the principles of the ‘Cooperative Planning’ procedure (Rütten, 1997; Rütten and Gelius, 2014) the framework was expanded. Cooperative Planning in health-promotion action research (Rütten, 1997) is a participatory approach that guides participants toward achieving a specified goal. From the beginning of the process, the participants share their decisions about objectives, implementation procedures, activities, and measures to be implemented. These aspects were considered in the further development of the framework, which took place after the working group meetings by the research team.

The second meeting for each of the three working groups occurred in the form of a telephone conference in January 2019. Prior to the conference call, participants were asked to review the previous findings on the key components within the expanded action-oriented framework (Stage 3) and to forward their feedback to the KOMBINE team. The participants’ comments were the starting point for the exchange during the telephone conference. All feedback about the newly developed framework and the relevance of key components during a specific phase were discussed until a consensus was reached (Stage 4).

Workshop 2 procedure

Workshop 2 took place in February 2019. The aim was to identify how to move from integrated evidence to the implementation of PA-related health promotion at the local level to facilitate structural changes and health equity. Special emphasis was placed on the presentation of a comparison of the key components (representing practice-based evidence) with updated literature (representing ‘scientific evidence’) regarding (i) the effectiveness of community-based PA-promotion measures focusing on population groups with social disadvantages and (ii) the determinants that influence the sustainable implementation of those measures. For this purpose, systematic literature searches in international databases had been conducted. The obtained results were synthesized narratively and formed the basis for a comparison between the current state of science (scientific knowledge) and practice-based knowledge (generated by means of the key components). The results of this comparison were also discussed with the participants during Workshop 2.

The second part of Workshop 2 used an interactive session with three newly composed working groups. All participants were assigned into three equal sized groups, each containing an equal proportion of community stakeholders, multipliers and policymakers. The aim was to discuss and pass the action-oriented framework jointly with all participants. For this purpose, all phases of the framework, including the relevant key components, were described in detail. Based on the core questions, ‘In your opinion, are the relevant aspects addressed?’ and ‘What other aspects do you see?’, the participants were encouraged by the moderators to share their views (see Supplementary Appendix 3). This yielded a unanimous decision for the finalized six-phase action-oriented framework within all three working groups and formed the basis for the implementation of the National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion at the local level within communities in Germany in Phase 2 of KOMBINE.

RESULTS

Participants

Overall, 74 participants attended the first KOMBINE workshop, 45 of whom were women and 29 were men. Forty-three were community stakeholders and 17 were multipliers. A total of 14 participants had a scientific background: seven academic staff members, three moderators, and four student assistants.

Concerning community stakeholders, the majority (N = 37) of the stakeholders were from the former West German states, and six were from the new German states. The proportion of community stakeholders from rural areas (N = 14), urban areas (N = 16) and metropolises (N = 13) was almost equally distributed.

In the working groups that took place between the two workshops, a total of 45 participants were involved. In the working group metropolis as well as rural area were 16 participants and in the working group urban area there were 13 participants. In total there were 23 community stakeholders and nine multipliers in the three working groups. Nineteen of the community stakeholders were from the former West German states, the other four from the new German states.

In the second KOMBINE workshop, a total of 52 attendees participated, with 27 women and 25 men. Of the participants, 28 were community stakeholders and 11 were multipliers. The distribution of participants with scientific background (N = 13) was almost equal to the first KOMBINE workshop, with seven academic staff members, three moderators and three student assistants.

Concerning community stakeholders, all participants were from states in former West Germany. Rural areas were slightly over-represented (N = 12) compared with urban areas (N = 9) and metropolises (N = 7) (see Supplementary Appendix 4).

Development of integrated evidence

The moderated group discussions in Workshop 1, which focused on facilitators, barriers and needs of community-based PA promotion regarding population groups with social disadvantages, resulted in a total of 270 notes from all participants. The number of notes ranged from n = 71 in the rural working group to n = 103 in the metropolis working group and n = 96 in the urban working group (see Supplementary Appendix 5).

The step-by-step sorting of the moderation cards with participants’ notes resulted in very similar clustered notes under each criterion (‘facilitators’, ‘barriers’, ‘needs’). Here content-related overlap between the three criteria became evident. For example, ‘integrate existing projects’ was a ‘facilitator’, but ‘no integration of existing projects’ was a ‘barrier’ or a ‘need’. Based on the content of the clustered notes overarching categories were summarized in the working groups. The notes within each working group did not lead to a different or additional category. Afterwards, the following nine key components based on the overarching categories were unanimously determined: ‘political support’, ‘integrating existing structures’, ‘cooperation and intersectoral partnership’, ‘participation’, ‘communication’, ‘competencies and qualification’, ‘strategic planning/methodical approach’, ‘infrastructural/financial/personal resources and timeframe’ and ‘offers/programs’ (Table 1). The final verification of these key components by participants within the meeting of each working group after Workshop 1 did not lead to an adaptation in the presented key components or the development of new key components.

Table 1:

Catalog of nine key components for successful and sustainable community-based PA promotion in Germany

| Key component | Content-related meaning | Examples of entries by working group |

|---|---|---|

| Political support | Awareness and integration of political decision-makers |

Rural areas: ‘Political will must be present’. Urban areas: ‘Political decision’. Metropolis: ‘Political support is important, especially at district level, in order to ensure sustainability from the outset’. |

| Integrating existing structures | Taking municipal issues into account |

Rural areas: ‘Create an overview of which services are already available’. Urban areas: ‘Involve stakeholders who already have services and access to target groups’. Metropolis: ‘Avoid parallel structures’. |

| Cooperation and intersectoral partnership | Interdisciplinary cooperation |

Rural areas: ‘Internal administrative communication between specialized services in which health, sport, social, and other services may be involved’. Urban areas: ‘Cooperation/alliance agreement’. Metropolis: ‘Cooperation is one of the greatest challenges, a position for an interdisciplinary coordinator must be created’. |

| Participation | Each individual should play a equal role in the process |

Rural areas: ‘Involve the target group as early as possible’. Urban areas: ‘Involve the specified target group’. Metropolis: ‘For high acceptance among the target group, involve them from the beginning’. |

| Communication | Find common language that is understandable for all participants, a ‘transparent course of action’ and ‘public relations’ |

Rural areas: ‘Regular information, e.g. through milestone plans’. Urban areas: ‘Materials for the planning process must be made available in such a way that they can be used, regardless of the level of education’. Metropolis: ‘Newsletter and participants' meetings for exchange’. |

|

Competence and qualification |

Expertise needs-oriented expansion |

Rural areas: ‘Qualification of the personnel assigned’. Urban areas: ‘Methods and implementation competence’. Metropolis: ‘Supervision for instructors and trainers’. |

| Strategic planning/methodical approach | Structured approach for planning and implementation |

Rural areas: ‘Monitoring of the individual work steps’. Urban areas: ‘Importance of neutral moderation’. Metropolis: ‘Adjust the qualification if necessary. Competence development (necessary for target group, multipliers and specialists to ensure sustainability)’. |

| Infrastructural/financial and personal resources, timeframe | Spatial, financial, personal availability, and a flexible timeframe |

Rural areas: ‘Clarify responsibilities and provide sufficient time’. Urban areas: ‘Identifying spaces: Creating new spaces, opening existing spaces…’ Metropolis: ‘Clarification: who assumes/shares in costs?’ |

| Offers/programs | Needs-oriented, appealing measures are provided and advertised |

Rural areas: ‘Identification of coordinated services for the target user community’. Urban areas: ‘Promotion of existing programs’. Metropolis: ‘Consideration of the nature of the problem’. |

To integrate practice-based evidence with scientific evidence, the next step included a comparison of these key components with the recent evidence from the literature regarding the effectiveness of community-based PA-promotion focusing on populations with social disadvantages (Ball et al., 2015; Conn and Coon Sells, 2016; Mendoza-Vasconez et al., 2016; Rütten and Pfeifer, 2016; Abu-Omar et al., 2017; Craike et al., 2018; Griffith et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2019). As a result, the determinants derived from the literature, as shown in Supplementary Appendix 6, demonstrated a high content overlap with the key components which were derived from the discussions with the participants. Only the key component ‘integrating existing structures’ was not described as a determinant of effective community-based PA-promotion in the available literature. Additionally, the accordance of the key components with the recent evidence from the literature (Draper et al., 2009; Cheadle et al., 2010; Schell et al., 2013; Edwards et al., 2014; Marlier et al., 2015; Herens et al., 2017) regarding determinants that influence sustainable implementation of community-based PA-promotion measures turned out to be high and showed a high content overlap with Schell et al.’s (Schell et al., 2013) core domains of the sustainability framework for public health programs. The high content overlap between the determinants derived from the literature and the key components was also discussed during Workshop 2 and was confirmed by the participants.

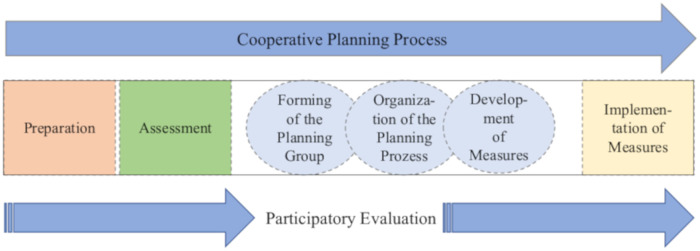

Development of the six-phase action-oriented framework

As a further result of the working group process, participants within all three groups agreed with the need to expand the three-phase framework. This led to the development of a six-phase action-oriented framework for community-based PA promotion suitable for all community sizes. The framework was extended by the following phases: ‘preparation’, ‘assessment’, ‘formation of a planning group’, ‘organization of the planning process’, ‘development of the measures’ and ‘implementation of the measures’ (Figure 1). It considers the feedback of the working groups according to which the initial three-phase framework model was helpful to start with as well as elements of the Cooperative Planning approach (Rütten, 1997; Rütten and Gelius, 2014) to foster the exchange and co-production of knowledge between different actors.

Fig. 1:

Six-phase action-oriented framework for community-based PA promotion.

In the following section, the relevance and content of key components within each phase of the framework based on the feedback of all workshops and working groups participants is described. All key components were mentioned in all six phases except for the key component ‘offers/programs’. However, participants focused on some key components more in specific phases compared with other phases. For example, the key components ‘cooperation and intersectoral partnership’ was mainly considered in the first three phases, while the key component ‘offers/programs’ was especially mentioned in the phases of development and implementation of measures. Therefore, the most relevant key components are presented for each phase.

As part of the preparation phase, participants indicated the early identification and motivation of, as well as information about, relevant political actors (e.g. mayors) and political bodies (e.g. representatives from the sports committee) to establish ‘political support’ (Key component 1). Participants considered this a very important first step to prepare the political decision-making process for the implementation of PA-promoting measures in communities. Furthermore, participants viewed political support as very important to building and maintaining sustainable structures. To ‘integrate existing structures’ (Key component 2), relevant political decision-makers from different sectors (e.g. health, sports, urban planning) as well as other relevant community actors (e.g. members of the community administration, experts) should be involved at a very early stage. Another central request was the formation of an intersectoral steering committee (see Supplementary Appendix 7) with political decision-makers and relevant community stakeholders, which addresses the ‘cooperation and intersectoral partnership’ (Key component 3). For ‘participation’ (Key component 4), participants emphasized the early involvement of individuals with social disadvantages and discussed the importance of an equal involvement of departments from different sectors that reach the entire population. Sensitizing the diverse actors for the participatory approach was also seen as important. Participants addressed ‘communication’ (Key component 5) to ensure transparency within the process as well as to motivate political and/or community stakeholders for cooperation. They suggested newspaper articles, informational letters, letters of intent, e-mail newsletters or the establishment of mailing lists for long-term network building as helpful tools. A further important task regarding communication was the definition of a kickoff format for KOMBINE in each community. Regarding ‘resources’ (Key component 8), participants suggested clarifying early on who bears the costs and supervises the project in the community.

With regard to the assessment phase, participants agreed on the key component ‘integrate existing structures’ to use accessible data relating to PA behavior (e.g. rates/data of PA), infrastructure (e.g. PA events), citizen participation (e.g. networks) and PA policy (e.g. political resolutions). Participants further stressed the importance of ‘participation’ (Key component 4) in this phase. This referred both to the participation of citizens and the participation of diverse actors and experts from the community in the assessment phase. For ‘communication’ (Key component 5), participants recommended informing relevant actors in a timely manner and ensuring transparency regarding the aims, contents and processes of the assessment phase. The importance of ‘strategic planning/methodical approach’ (Key component 7) was also highlighted to integrate relevant data from different sectors in a timely manner. Considering ‘resources’ (Key component 8), participants mentioned data sources in communities and the calculation of time and costs for staff.

The phase forming a planning group mainly addressed the final identification and invitation of relevant participants for the Cooperative Planning group. For ‘political support’ (Key component 1), participants highlighted the involvement of mayors, local councils and representatives from country committees. They further emphasized the importance of ‘integrating existing structures’ (Key component 2) by involving representatives (e.g. from schools, family centers, sport clubs) from already existing work groups in the Cooperative Planning group. For ‘cooperation and intersectoral partnership’ (Key component 3), participants recommended an early signed cooperation agreement between all group members and the selection of one responsible representative from each institution/department who attends meetings regularly. Within ‘participation’ (Key component 4), participants stressed the importance of the early involvement of individuals with social disadvantages. About Key component 5, ‘communication’, the use of a common, clear language and the provision of easily understandable materials for the planning process were mentioned. Participants also emphasized the importance of a consensus on the definition used for PA and health promotion and a shared vision and common understanding of the process. Another aspect was to provide information on a regular basis. In relation to the ‘strategic planning/methodical approach’ (Key component 7), participants discussed the role and tasks of a steering committee and the planning group (see Supplementary Appendix 7). A shared vision and common understanding of the process was also viewed as important. Participants also mentioned a research assistant who supports the formation of a Cooperative Planning group. As an important ‘resource’ (Key component 8), participants proposed designating one responsible community representative for the planning groups (e.g. ‘champion’).

In the phase organization of the planning process, participants discussed the political decision-making process for implementing PA-promotion measures in ‘political support’ (Key component 1). Some participants mentioned that a resolution should be in place before the initial process of developing and implementing PA-promotion measures. However, other participants preferred to start with the implementation process followed by the political decision-making process. With regard to ‘participation’ (Key component 4), ensuring that every participant of the Cooperative Planning group be able to equally participate during meetings was noted. ‘Communication’ (Key component 5) included aspects of, e.g. transparency, regular information updates, regular exchange between the steering committee and the Cooperative Planning group, and establishing a mailing list with all planning group members to convey information between meetings. Regarding ‘strategic planning/methodical approach’ (Key component 7), participants discussed the number of meetings, the number of group members, the need for a timetable (including objectives, milestones, tasks with defined responsibilities), the determination of a neutral and trained moderator, the need for a quality management system for the planning process, and the definition of pragmatic indicators to evaluate the success of developed PA-promoting measures. Participants also agreed that the formation of smaller, context-related working groups within the Cooperative Planning group would be helpful to develop specific PA-promoting measures. For ‘resources’ (Key component 8), participants discussed the required preparation time and revision of meetings (e.g. five to six meetings within 1 year, each with a duration of 1.5−2 h), and the required personnel resources (e.g. one responsible person who coordinates the process within each community).

During the phase development of measures, participants viewed a cooperation agreement for newly developed PA-promoting measures as important for ‘cooperation and intersectoral partnership’ (Key component 3). Participants emphasized again the importance of ensuring full ‘participation’ (Key component 4) of individuals with social disadvantages and considering the needs of each member of the Cooperative Planning group and steering committee. In relation to ‘strategic planning/methodical approach’ (Key component 7), the participants agreed that it would be helpful to start with (i) brainstorming ideas, (ii) setting priorities, (iii) developing the PA-promoting measures and (iv) approving an action plan with defined objectives, tasks, responsibilities, timelines, milestones and pragmatic indicators of success. The participants also agreed that public relations for each developed PA-promoting measure would be helpful for the key component ‘communication’ (Key component 5). Concerning ‘offers/programs’ (Key component 9), participants emphasized that existing offers/programs should be improved, and new offers only developed where necessary.

Throughout the last phase, implementation of measures, Cooperative Planning group members were required to vote on the developed PA-promoting measures and pass the action plan. If ‘political support’ (Key component 1) was not carried out in the earlier phases, it would be important that political decision-making on PA-promoting measures take place at this time. Regarding ‘cooperation and intersectoral partnership’ (Key component 3), participants recommended that working groups should continue to meet even after the measures are implemented. For ‘participation’ (Key component 4), participants emphasized again that individuals with social disadvantages must be fully involved in this phase. ‘Competence and qualification’ (Key component 6) were addressed more often than in the previous phases. Participants pointed out that staff who are working with individuals with social disadvantages would need professional expertise on how to reach target groups. For the key component ‘strategic planning/methodical approach’ (Key component 7), participants discussed the monitoring of single process steps and the implementation of a participatory evaluation approach. In regard to ‘resources’ (Key component 8), participants discussed that a full-time network coordinator would be necessary in order to ensure the sustainability of the implemented PA-promoting measures. They further stressed that appropriate financial resources must be available, even after the project ends. Participants also indicated that personnel consistency is important for successful implementation. With regard to ‘programs/offers’ (Key component 9), participants recommended the development and implementation of PA-promoting measures not only in sports club but also in other settings. Some participants were unsure about sports clubs and their readiness to address the needs of population groups with social disadvantages. Hence, participants again recommended the use of multipliers working in practice (e.g. social workers) to reach groups with social disadvantages.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we describe a systematic activation and co-producing process for the implementation of the National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion in German communities within KOMBINE. During Phase 1, we involved key stakeholders in a series of workshops and working group meetings and discussed their specific experiences in health promotion focusing on PA and health equity. Further essential outcomes were a six-phase action-oriented framework and an included catalog of nine key components. Both represent a shared vision on how to implement the National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion with a focus on health equity at the local level.

The co-produced six-phase action-oriented framework including the key components serves as a practical tool and allows adaptions to the local context. This is important at the operational level to implement PA-related health promotion and in the long term is essential for the successful and sustainable implementation of the National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion. The framework also encompasses the principles of the Cooperative Planning procedure, which builds on voluntary collaboration to overcome the inertia of established structures (Rütten, 1997; Rütten and Gelius, 2014).

There are numerous evidence-based frameworks available for the purpose of dissemination and implementation (Glasgow et al., 1999; Rogers, 2003; Tabak et al., 2018). Although they do provide sound guidance for several subject areas, they are not specifically designed to integrate practice-based and scientific knowledge on a given topic. Advantages of co-producing action-oriented frameworks have been also reported for other complex public health issues (Hendriks et al., 2013; Kastelic et al., 2018; Greenhalgh et al., 2019; Leask et al., 2019; Daly-Smith et al., 2020).

The action-oriented framework in our study specifically considers practice-based knowledge from diverse community stakeholders, multipliers and policymakers regarding the identified facilitators, barriers, and needs for community-based PA promotion that are represented in the nine key components and their involvement in the six phases. On the other hand, it reflects scientific knowledge regarding the effective and sustainable implementation of community-based PA promotion with a focus on health equity. The integration of practice-based knowledge and scientific knowledge has been discussed as crucial to translate research into practice (Green, 2006; Glasgow et al., 2012; Chambers et al., 2013; Ammerman et al., 2014). This was addressed by the process of the co-production of the framework in Phase 1 of KOMBINE.

The catalog of key components links two public health issues, namely physical inactivity, and health inequity, and contains strategies to implement community-based PA promotion based on the experiences of all participants. By comparing these key components with updated literature on effective and sustainable community-based PA promotion considering populations with social disadvantages, there were major content overlaps (Draper et al., 2009; Cheadle et al., 2010; Schell et al., 2013; Edwards et al., 2014; Ball et al., 2015; Marlier et al., 2015; Conn and Coon Sells, 2016; Mendoza-Vasconez et al., 2016; Herens et al., 2017; Craike et al., 2018; Griffith et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2019). In the following section, we will discuss key findings in selected key components.

The importance of the key component political support in the development and implementation of PA promotion, including PA-related policies and regulations, is supported by several studies and guidelines (Bauman et al., 2012; Heath et al., 2012; Rütten and Pfeifer, 2016). For instance, political support is necessary to provide and allocate resources (Bauman et al., 2012; Ball et al., 2015; Marlier et al., 2015). A lack of political support for the implementation of PA-promoting measures with a focus on populations with social disadvantages has been identified as a barrier in the literature (Herens et al., 2017) and also at the workshops and working group meetings in KOMBINE. Participants in our study acknowledged the importance of political support in implementing effective and sustainable community-based PA promotion in the local context. They mainly referred to the question of which political actors and committees should be involved and the optimal timing of political decision-making processes for the implementation of measures.

Cooperation and intersectoral partnerships are needed not only to initiate the implementation of PA promotion in the local context; ideally, they develop further during the process and are also an outcome of a collective effort (Herens et al., 2017). The implementation of a whole-system approach to PA-related health promotion in the community with a particular focus on population groups with social disadvantages is a complex societal challenge that requires cooperation of diverse sectors within a community, as recommended by several PA guidelines [i.e. (European Commission, 2008; Rütten and Pfeifer, 2016; World Health Organization, 2018)]. This was also requested by the workshop participants, who stressed the importance of involving stakeholders right at the beginning of the project. According to the participants and current literature (Ball et al., 2015; Herens et al., 2017), those intersectoral partnerships are also helpful in providing resources and skills to develop sustainable solutions.

The participation of the community in general and the involvement of populations with social disadvantages in particular in the development and implementation of PA-promoting measures is associated with higher effectiveness (Draper et al., 2009; Craike et al., 2018) and prolonged continuation of programs (Draper et al., 2009). A participation process that considers specific experiences and needs empowers individuals as well as communities (Draper et al., 2009; Cheadle et al., 2010). The participants in our workshops also emphasized the early and continuous participation of individuals with social disadvantages for the entire community-based PA-promotion process.

The key component integrating existing structures could not be identified based on the included reviews (Schell et al., 2013; Ball et al., 2015; Conn and Coon Sells, 2016; Mendoza-Vasconez et al., 2016; Abu-Omar et al., 2017; Craike et al., 2018; Griffith et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2019). This might be related to the fact that most of the reviews assessed the effectiveness of already developed and implemented interventions. To integrate existing structures therefore might have been beyond the scope of the studies included in the reviews. The integration of existing structures was intensively discussed through Phase 1 until 2 by the participants in our workshops. They specified this by the integration of existing local projects, networks, offers, community centers, as well as various actors like relevant associations, organizations and institutions.

The high content overlap between the key components and findings of the literature could be influenced by the inclusion of key stakeholders in the field of health and PA promotion. These participants either have professional knowledge based on their qualifications or may have benefited in recent years from existing health promotion activities in communities in Germany, which were offered by various organizations on the federal, national or local level (RKI, 2015). Participation in Phase 1 was voluntary and this may have led to the participation of people who were very interested in the topic. Another reason could be the chosen methodological approach in our study. It could be argued that the participants were informed about the current state of the evidence and then expressed their agreement with the findings. However, we developed the key components before we presented the findings of the literature and the high level of content overlap with the key components in Workshop 2. The participants had the opportunity to discuss and verify the high level of content overlap. Finally, despite the high content overlap between the key components and findings of the literature in general the participants provided more details regarding the relevance of each key component in the six phases of the action-oriented framework. In our view, this represents a strength of the transdisciplinary approach with the result of a bottom-up developed action-oriented framework that considers practice-based knowledge as well scientific knowledge. The action-oriented framework serves therefore not only as a shared vison, but also provides guidance on how to implement KOMBINE and the National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion. This is important, as the promotion of health equity and PA-related health promotion at the local level in Germany requires structural changes in the provision of preventive and health-promoting services.

Challenges and limitations

Individuals with social disadvantages did not take part in Phase 1 of KOMBINE. The aim of Phase 1 of KOMBINE was to activate stakeholders and co-produce an action-oriented framework on the national level for the implementation of community-based PA promotion. This requires key stakeholders from communities with professional knowledge about the communities and in working with socially disadvantaged population groups as well as multipliers and policymakers with professional knowledge of the context of health and PA promotion in Germany. The participation of population groups with social disadvantages is planned throughout Phase 2 of KOMBINE. During this phase, it will be ensured that participants with social disadvantages in all six pilot communities can share their experiences and needs about community-based PA promotion. It will be further ensured that they have the opportunity to participate in the entire process of implementing and testing the action-oriented framework as emphasized within the key component ‘participation’ by the workshop participants.

Even though workshop participants were recruited nationwide, and meetings took place in a central location in Germany, most of the participants were from the former West German states. Within the acquisition of workshop participants, we received responses from stakeholders of the new German states that they lacked the personnel or financial resources to participate in the workshops. This might be related to the higher socioeconomic deprivation level in the new German states compared with the former West German states (Kroll et al., 2017). In addition, in the first phase, less participants from the new German states took part in Workshop 2. According to feedback from two participants, this was due to time reasons. The small number of participants from communities of the new German states may have influenced our outcomes, and the missing experiences and perspectives of those relevant participants could reduce the nationwide applicability of the framework.

Another limitation relates to the comparison of the key components (practice-based evidence) with updated literature reviews (scientific evidence). Since the respective literature reviews were updated during the process of Phase 1, the narrative comparison of the practice-based evidence and the scientific evidence was based on the first available results. Therefore, a more in-depth analysis could provide further insights.

Finally, the inductive approach of developing key components based on the notes regarding facilitators, barriers and needs of workshop participants by the research team might have been influenced by their individual experiences. Nevertheless, the guided moderation as well as the iterative process of several opportunities for discussion ensure that the key components represent the experiences of the diverse actors involved.

Future steps

Within the scope of the second phase of KOMBINE, the six-phase action-oriented framework is currently being pilot tested in one metropolis, two urban and three rural communities. The ongoing evaluation approach will show if, in practice, the co-produced framework successfully tackles implementation challenges and facilitates structural changes for PA-related health promotion.

In particular, the KOMBINE project intends to investigate if such co-production processes can be harmonized across the different communities involved, as the action framework suggests. Such knowledge would be highly valuable to improve the scalability of community-based PA-promotion efforts, paving the way for a broader implementation of the German National Recommendations for PA and PA Promotion with a focus on improving health equity.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Health Promotion International online.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Federal Center of Health Education (BZgA) on behalf of and with funds from the statutory health insurances according to § 20a SGB V in the context of the GKV Alliance for Health (www.gkv-buendnis.de). Grant number: Z2/1.01 G/18.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The work was approved by the independent Research Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany (13 September 2019; Ref. No. 321_15B).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Blanca Güßmann, Maja Porschert and Diana Richardson for help in preparing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Abu-Omar K., Messing S., Sarshar M., Gelius P., Ferschl S., Finger J.. et al. (2021) Sociodemographic correlates of physical activity and sport among adults in Germany: 1997–2018. German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research, 51, 170–182. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Omar K., Rütten A., Burlacu I., Messing S., Pfeifer K., Ungerer-Röhrich U. (2017) Systematischer Review von Übersichtsarbeiten zu Interventionen der Bewegungsförderung: methodologie und erste Ergebnisse. Das Gesundheitswesen, 79, S45–S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Omar K., Rütten A., Messing S., Pfeifer K., Ungerer-Röhrich U., Goodwin L.. et al. (2019) The German recommendations for physical activity promotion. Journal of Public Health, 27, 613–627. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman A., Smith T. W., Calancie L. (2014) Practice-based evidence in public health: improving reach, relevance, and results. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 47–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K., Carver A., Downing K., Jackson M., O'Rourke K. (2015) Addressing the social determinants of inequities in physical activity and sedentary behaviours. Health Promotion International, 30, ii8–ii19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman A. E., Reis R. S., Sallis J. F., Wells J. C., Loos R. J., Martin B. W. (2012) Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet, 380, 258–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron C., Craig C. L., Bull F. C., Bauman A. (2007) Canada’s physical activity guides: has their release had an impact? Applied Physiology. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 32, S161–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers D. A., Glasgow R. E., Stange K. C. (2013) The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science, 8, 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle A., Egger R., LoGerfo J. P., Schwartz S., Harris J. R. (2010) Promoting sustainable community change in support of older adult physical activity: evaluation findings from the Southeast Seattle Senior Physical Activity Network (SESPAN). Journal of Urban Health : Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 87, 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn V. S., Coon Sells T. G. (2016) Effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity among minority populations: an umbrella review. Journal of the National Medical Association, 108, 54–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craike M., Wiesner G., Hilland T. A., Bengoechea E. G. (2018) Interventions to improve physical activity among socioeconomically disadvantaged groups: an umbrella review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 15, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly-Smith A., Quarmby T., Archbold V. S. J., Corrigan N., Wilson D., Resaland G. K.. et al. (2020) Using a multi-stakeholder experience-based design process to co-develop the creating active schools framework. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper C. E., Kolbe-Alexander T. L., Lambert E. V. (2009) A retrospective evaluation of a community-based physical activity health promotion program. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 6, 578–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards M. B., Theriault D. S., Shores K. A., Melton K. M. (2014) Promoting youth physical activity in rural southern communities: practitioner perceptions of environmental opportunities and barriers. The Journal of Rural Health, 30, 379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2008) EU Physical Activity Guidelines. Recommended Policy Actions in Support of Health-enhancing Physical Activity. https://bit.ly/3aZNyLY (last accessed 08 October 2021).

- Finger J., Mensink G., Lange C., Manz K. (2017) Gesundheitsfördernde körperliche Aktivität in der Freizeit bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland. Journal of Health Monitoring, 2, 37–44. 10.17886/RKI-GBE-2017-027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich K. L., Potvin L. (2008) Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 216–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainforth H. L., Berry T., Faulkner G., Rhodes R. E., Spence J. C., Tremblay M. S.. et al. (2013) Evaluating the uptake of Canada's new physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines on service organizations' websites. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 3, 172–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R. E., Green L. W., Taylor M. V., Stange K. C. (2012) An evidence integration triangle for aligning science with policy and practice. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42, 646–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R. E., Vogt T. M., Boles S. M. (1999) Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 1322–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M., Davis A. (2019) Translating evidence into practice. In Nieuwenhuijsen M., Khreis H. (eds), Integrating Human Health into Urban and Transport Planning: A Framework. Springer, Berlin, pp. 655–681. [Google Scholar]

- Green L. W. (2006) Public health asks of systems science: to advance our evidence-based practice, can you help us get more practice-based evidence? American Journal of Public Health, 96, 406–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Hinton L., Finlay T., Macfarlane A., Fahy N., Clyde B.. et al. (2019) Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: systematic review and co-design pilot. Health Expectations, 22, 785–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M., Bergner E. M., Cornish E. K., McQueen C. M. (2018) Physical activity interventions with African American or Latino Men: a systematic review. American Journal of Men's Health, 12, 1102–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath G. W., Parra D. C., Sarmiento O. L., Andersen L. B., Owen N., Goenka S.. et al. (2012) Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: lessons from around the world. The Lancet, 380, 272–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks A.-M., Jansen M. W., Gubbels J. S., De Vries N. K., Paulussen T., Kremers S. P. (2013) Proposing a conceptual framework for integrated local public health policy, applied to childhood obesity—the behavior change ball. Implementation Science, 8, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herens M., Wagemakers A., Vaandrager L., van O. J., Koelen M. (2017) Contexts, mechanisms, and outcomes that matter in Dutch community-based physical activity programs targeting socially vulnerable groups. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 40, 294–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.-L., Junge K., Nguyen A., Hiegel K., Somerville E., Keglovits M.. et al. (2019) Evidence to improve physical activity among medically underserved older adults: a scoping review. The Gerontologist, 59, e279–e293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (1988) The Future of Public Health. National Academies Press (US; ), Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn T., Bergmann M., Keil F. (2012) Transdisciplinarity: between mainstreaming and marginalization. Ecological Economics, 79, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kastelic S. L., Wallerstein N., Duran B., Oetzel J. G. (2018) Socio-ecologic framework for CBPR: development and testing of a model. In Wallerstein N., Duran B., Oetzel J. G., Minkler M. (eds), Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. Jossey-Bass & Pfeiffer Imprints Wiley, San Francisco, pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll L. E., Schumann M., Hoebel J., Lampert T. (2017) Regional Health Differences – Developing a Socioeconomic Deprivation Index for Germany. Georg Thieme Verlag KG, Stuttgart, New York. 10.17886/RKI-GBE-2017-048.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Leask C. F., Sandlund M., Skelton D. A., Altenburg T. M., Cardon G., Chinapaw M. J. M., et al. ; GrandStand, Safe Step and Teenage Girls on the Move Research Groups. (2019) Framework, principles and recommendations for utilising participatory methodologies in the co-creation and evaluation of public health interventions. Research Involvement and Engagement, 5, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone L., Pesce C. (2017) From delivery to adoption of physical activity guidelines: realist synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14, 1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenc T., Petticrew M., Welch V., Tugwell P. (2013) What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67, 190–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlier M., Lucidarme S., Cardon G., De Bourdeaudhuij I., Babiak K., Willem A. (2015) Capacity building through cross-sector partnerships: a multiple case study of a sport program in disadvantaged communities in Belgium. BMC Public Health, 15, 1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Vasconez A. S., Linke S., Muñoz M., Pekmezi D., Ainsworth C., Cano M.. et al. (2016) Promoting physical activity among underserved populations. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 15, 290–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NPK. (2019) Die Nationale Präventionskonferenz: Erster Präventionsbericht. Nach § 20d Abs. 4 SGB V. Berlin. https://bit.ly/3ePpWe3 (last accessed 30 April 2021).

- Nutbeam D., Muscat D. M. (2021) Health promotion glossary 2021. Health Promotion International. 10.1093/heapro/daaa157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2020) Addressing Societal Challenges Using Transdisciplinary Research. OECD Publishing, Paris, 10.1787/0ca0ca45-en [DOI]

- RKI. (2015). Gesundheit in Deutschland - Einzelkapitel: Wie steht es um Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung? https://bit.ly/3tdII46 (last accessed 30 April 2021).

- Rogers E. M. (2003) Diffusion of Innovations, 5th edition. Free Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Rütten A. (1997) Kooperative Planung und Gesundheitsförderung: ein Implementationsansatz. Journal of Public Health, 5, 257–272. [Google Scholar]

- Rütten A., Abu-Omar K., Messing S., Weege M., Pfeifer K., Geidl W.. et al. (2018) How can the impact of national recommendations for physical activity be increased? Experiences from Germany. Health Research Policy and Systems, 16, 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rütten A., Frahsa A., Abel T., Bergmann M., Leeuw E., de, Hunter D.. et al. (2019) Co-producing active lifestyles as whole-system-approach: theory, intervention and knowledge-to-action implications. Health Promotion International, 34, 47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rütten A., Gelius P. (2014) Building policy capacities: an interactive approach for linking knowledge to action in health promotion. Health Promotion International, 29, 569–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rütten A., Pfeifer K. (eds). (2016) National Recommendations for Physical Activity and Physical Activity Promotion. FAU University Press, Erlangen, pp. 19–65. [Google Scholar]

- Schell S. F., Luke D. A., Schooley M. W., Elliott M. B., Herbers S. H., Mueller N. B.. et al. (2013) Public health program capacity for sustainability: a new framework. Implementation Science, 8, 15–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D., Hall K. L., Vogel A. (2013) Transdisciplinary public health: definitions, core characteristics, and strategies for success. In Haire-Joshu D., McBride T. D. (eds), Transdisciplinary Public Health: Research, Education, and Practice, 1st edition. Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco, pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- SVR Gesundheit. (2007) Gutachten 2007 des Sachverständigenrates zur Begutachtung der Entwicklung im Gesundheitswesen: Kooperation und Verantwortung – Voraussetzungen einer zielorientierten Gesundheitsversorgung. Drucksache 16/6339. http://dipbt.bundestag.de/dip21/btd/16/063/1606339.pdf (last accessed 30 April 2021).

- Tabak R. G., Chambers D. A., Hook M., Brownson R. (2018) The conceptual basis for dissemination and implementation research dissemination and implementation research in health. In Brownson R. C., Colditz G. A., Proctor E. K. (eds), Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2018) More Active People for a Healthier World: Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018-2030. World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.