Abstract

Cardiopatía Isquémica Crónica e Hipertensión Arterial en la Práctica Clínica en España (CINHTIA) was a survey designed to assess the clinical management of hypertensive outpatients with chronic ischemic heart disease. Sex differences were examined. Blood pressures (BP) was considered controlled at levels of <140/90 or <130/80 mm Hg in diabetics (European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology 2003); low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) was considered controlled at levels <100 mg/dL (National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III). In total, 2024 patients were included in the study. Women were older, with a higher body mass index and an increased prevalence of atrial fibrillation. Dyslipidemia, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and peripheral arterial disease were more frequent in men. In contrast, diabetes, left ventricular hypertrophy, and heart failure were more common in women. BP and LDL‐C control rates, although poor in both groups, were better in men (44.9% vs 30.5%, P<.001 and 33.0% vs 25.0%, P<.001, respectively). Stress testing and coronary angiography were more frequently performed in men.

Cardiovascular disease is the most important cause of death among women. 1 Moreover, the progressive aging of the population, a sedentary lifestyle, and the increased prevalence of diabetes and obesity may worsen this situation in the future. 2 , 3 Despite that, it seems that many physicians and patients do not actually perceive the coronary risk in women. 4 This could be at least partially due to confidence in the well‐known cardioprotective effect of female hormones but also to the fact that, in the past decades, most clinical trials included primarily male patients. As a result, many physicians have not realized the frequency of heart disease in women. 2 Fortunately, in the last few years the information provided from different studies has increased the sensitivity of this issue. 2 , 5 More information is necessary for better clinical management in this population.

Treatment of hypertension markedly reduces the risk of ischemic disease. 6 Current recommendations establish that patients with hypertension and coronary heart disease should be treated aggressively to attain blood pressure (BP) targets lower than those in the general population. 2 , 7 , 8 A growing interest in the association of hypertension and ischemic heart disease led to the recent publication of a statement from the American Heart Association on this topic. 8

Although some surveys devoted to patients with ischemic heart disease have been developed and have assessed the clinical profile of this population, 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 there is only limited information specifically focused on hypertensive patients with coronary heart disease. Cardiopatía Isquémica Crónica e Hipertensión Arterial en la Práctica Clínica en España (CINHTIA) is a cross‐sectional multicenter survey to determine the clinical profile and management of hypertensive outpatients with chronic ischemic heart disease attended by cardiologists in clinical practice in Spain. In this manuscript, the influence of sex on these issues is examined.

Patients and Methods

A total of 112 investigators, all cardiologists, participated in this study performed during the second quarter of 2006. Each investigator was asked to include consecutive patients aged 18 years or older, male or female, with an established diagnosis of hypertension and chronic ischemic heart disease. Patients with an acute coronary syndrome within the previous 3 months before inclusion were excluded. Biodemographic data, risk factors, history of cardiovascular disease, and the different treatments patients were receiving were recorded. All patients underwent a complete physical examination and had a complete blood test (hematology and biochemistry with a lipid profile) performed within the previous 6 months.

BP readings were taken following the 2003 European guidelines. 13 The visit BP was the average of 2 separate measurements taken by the examining physician; a third measure was obtained when there was a difference of ≥5 mm Hg between the 2 readings. Hypertension was diagnosed when patients had a systolic BP level ≥140 mm Hg or a diastolic BP level ≥90 mm Hg (130/80 mm Hg, respectively, for diabetics) or a history of hypertension and taking antihypertensive medication. Adequate BP control was defined as a systolic BP level <140 mm Hg and a diastolic BP level <90 mm Hg (<130 and <80 mm Hg for diabetics). 13 Low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) <100 mg/dL was considered under good control. 14 Sedentary lifestyle was defined as physical activity less than a 30‐minute daily walk.

Chronic ischemic heart disease was defined by any of the following: stable angina, clinically defined as typical chest pain with the demonstration of myocardial ischemia that occurs on exertion and is relieved by rest; evidence of myocardial ischemia assessed by any stress test performed >3 months before inclusion in the study; a history of myocardial infarction; or previous revascularization more than 3 months before the trial. The presence of organ damage or associated clinical conditions was recorded from the patients’ clinical history. Renal insufficiency was considered to be a serum creatinine level >1.5 mg/dL in men and >1.4 mg/dL in women. 13 The diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy was established by electrocardiography (Sokolow–Lyon voltage >38 mm; Cornell voltage duration product >2440 mm×ms) and/or echocardiography (left ventricular mass index ≥125 g/m2 in men and ≥110 g/m2 in women). 13

Statistical Analysis

Chi‐square testing was used to analyze the relationship between categorical variables. Comparison of continuous variables between groups was performed using the Student’s t‐test. A logistic regression analysis was performed to determine which factors could be associated with BP control. Clinical characteristics of study population, cardiovascular risk factors, organ damage, antihypertensive treatments, concomitant treatments, and biochemical parameters were included as independent variables in the logistic regression analysis. A P value <.05 was used as the level of statistical significance. Database recording was subjected to internal consistency rules and ranges to control inconsistencies/inaccuracies in the collection and tabulation of data (SPSS version 12.0, Data Entry, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

In the CINHTIA study, a total of 2024 hypertensive patients with chronic ischemic heart disease were included (31.7% female). Table I summarizes the biodemographic data, cardiovascular risk factors, organ damage, physical examination results, and laboratory parameters. Women were older and had a higher body mass index and an increased prevalence of atrial fibrillation. Although angina was the most frequent clinical presentation in both sexes, it was more common in women. By contrast, the history of myocardial infarction and revascularization was significantly more common in men. The presence of concomitant cardiovascular risk factors and organ damage was common in both sexes. Dyslipidemia, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and peripheral arterial disease were more frequent in men and diabetics; left ventricular hypertrophy and heart failure were more common in women. Systolic and diastolic BP, heart rate, total cholesterol, LDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol and serum fasting glucose values were higher in women, while serum uric acid levels were higher in men.

Table I.

Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population (N=2024)

| Male (n=1382; 68.3%) | Female (n=642; 31.7%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 65.7±10.3 | 68.2±9.1 | <.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.0±3.5 | 28.8±4.6 | .001 |

| Atrial fibrillation, % | 13.3 | 23.8 | <.0001 |

| LVEF, % | 57.4±11.4 | 58.6±11.6 | .25 |

| Clinical manifestation of chronic ischemic heart diseasea | |||

| Angina, % | 67.0 | 73.3 | .003 |

| Myocardial infarction, % | 48.7 | 34.3 | <.0001 |

| Revascularization, % | 48.5 | 33.8 | <.0001 |

| Evidence of ischemia, % | 39.4 | 43.7 | .042 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Dyslipidemia, % | 80.0 | 75.2 | .009 |

| Current smoker, % | 15.5 | 5.2 | <.0001 |

| Ex‐smoker (>1 year quit smoking), % | 41.4 | 10.2 | <.0001 |

| Diabetes, % | 27.3 | 43.2 | <.0001 |

| Sedentary lifestyle, % | 75.4 | 60.9 | <.0001 |

| Metabolic syndrome, % | 53.9 | 66.1 | <.0001 |

| Organ damage | |||

| Left ventricular hypertrophy, % | 46.6 | 54.9 | .001 |

| Heart failure, % | 14.5 | 26.8 | <.0001 |

| Peripheral artery disease, % | 18.5 | 10.3 | <.0001 |

| Renal function insufficiency, % | 12.4 | 12.7 | .88 |

| Stroke, % | 7.9 | 9.6 | .24 |

| Physical examination | |||

| SBP, mm Hg | 141.1±17.8 | 146.3±17.5 | <.0001 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 81.2±11.2 | 83.2±11.3 | <.0001 |

| HR, beats/min | 68.5±11.0 | 71.5±10.6 | <.0001 |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 195.4±44.3 | 207.8±42.4 | <.0001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 142.8±78.9 | 147.4±73.4 | .24 |

| LDL‐C, mg/dL | 114.4±36.4 | 119.6±34.4 | .004 |

| HDL‐C, mg/dL | 49.3±18.7 | 51.2±16.5 | .04 |

| Serum fasting glucose, mg/dL | 114.6±35.7 | 125.8±43.5 | <.0001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.24±1.3 | 1.18±1.2 | .33 |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 7.1±6.9 | 6.5±5.6 | .09 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; HR, heart rate; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SBP, systolic blood pressure. aA patient may have more than one diagnosis.

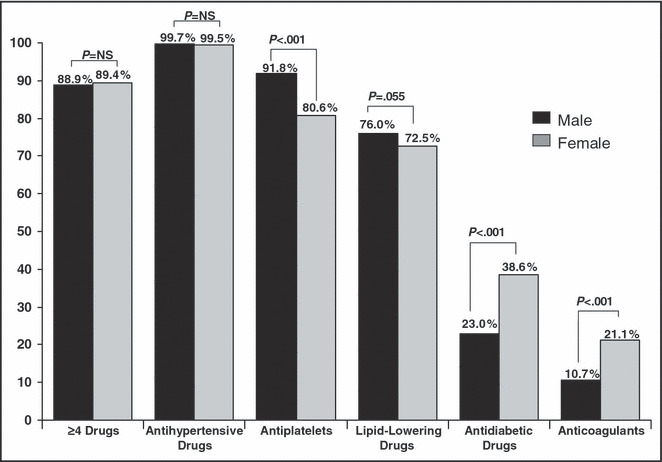

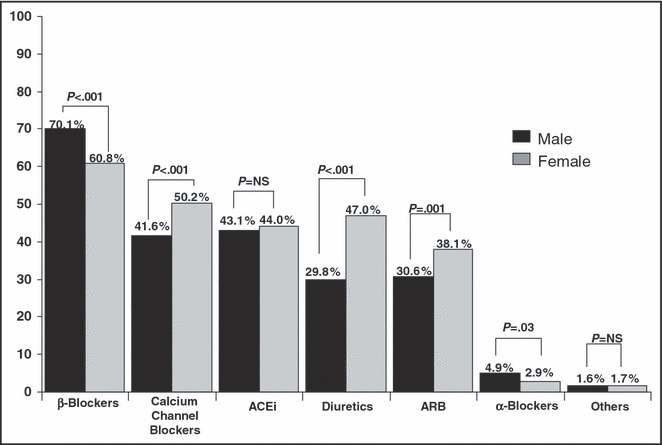

Almost all patients were taking at least 4 drugs, without significant differences between sexes. However, men were taking more antiplatelet agents and showed a trend toward using more lipid‐lowering drugs. Antidiabetic medication and anticoagulants were used more frequent in women (Figure 1). In Figure 2, the prescribed antihypertensive drugs are listed. β‐Blockers were the agents most commonly used in both groups. Though the total number of drugs was similar in both sexes, distribution differed. Thus, the prescription of β‐ and α‐blockers were more common in men, and calcium channel blockers, diuretics, and angiotensin receptor blockers were more common in women.

Figure 1.

Treatment of the study population.

Figure 2.

Antihypertensive medication in the study. ACEi indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers.

Overall BP and LDL‐C control rates (Figure 3) were better in men than in women (44.9% vs 30.5%, P<.001 and 33.0% vs 25.0%, P<.001, respectively). With a BP goal <130/80 mm Hg (current guidelines recommended for hypertensive patients with concomitant coronary heart disease or diabetes), BP control was also worse in women (27.2% vs 17.7%, P=.001). In a multivariate analysis, female sex was a predictor of poor BP control (odds ratio, 1.43; 95% confidence interval, 1.08–1.90). BP control rates were also analyzed according to the clinical manifestations of chronic ischemic heart disease (Table II). In all cases (angina, evidence of ischemia, myocardial infarction, or previous revascularization), BP control rates were higher in men. In both sexes, the history of revascularization was associated with better BP control rates.

Figure 3.

Blood pressure and low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) control rates.

Table II.

Blood Pressure (BP) Control Rates According to the Different Clinical Manifestations of Chronic Ischemic Heart Disease

| Clinical Manifestation of Chronic Ischemic Heart Disease | BP Control Rates (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| Angina | 42.4 | 28.6 | <.001 |

| Evidence of ischemia | 43.8 | 33.2 | <.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 48.3 | 31.2 | <.001 |

| Revascularization | 47.7 | 37.0 | <.001 |

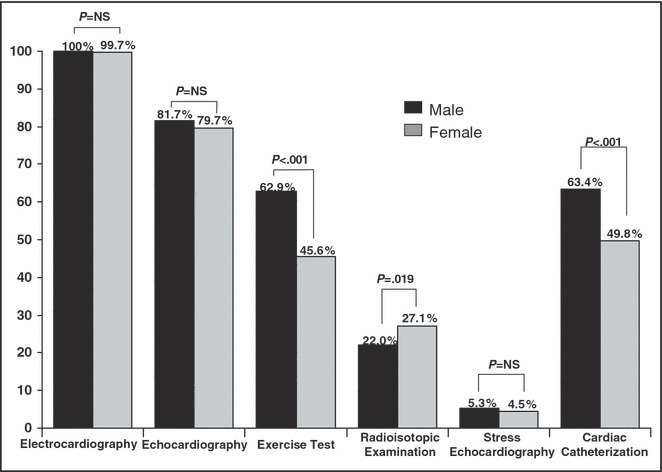

Finally, the diagnostic methods used in this population according to sex were examined. Exercise tests and cardiac catheterization tests were more commonly performed in men, and radioisotopic examinations were performed more in women, without differences in the frequency of electrocardiography, echocardiography, or stress echocardiography (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Diagnostic procedures according to sex.

Discussion

Epidemiologic studies have established a strong association between hypertension and coronary heart disease. Indeed, about 10% of hypertensive patients who are seen in primary care settings and >20% seen in cardiologist clinics have ischemic heart disease. 15 On the other hand, more than three‐quarters of patients with coronary artery disease have a clinical history of hypertension. 16 Despite that coronary heart disease has been traditionally considered a male illness, data show that this is one of the most important causes of mortality in women. 1 Moreover, recent studies have reported that women with acute coronary syndromes have a similar number of 17 , 18 or even more morbid events than do men. 19

Several studies in the past few years have assessed the differences between sexes in clinical findings and management of coronary heart disease. There is little information about these differences in the hypertensive population. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 17 , 18 The CINHTIA survey may provide relevant information about sex differences.

Because patients included in randomized clinical trials are selected and may not always represent the “real world” of daily practice, the development of this type of survey may be of clinical interest. 20 The results clearly show that there are significant differences between sexes in the clinical profile; women are older and more obese. The presence of concomitant cardiovascular risk factors and organ damage was common in both sexes. But while dyslipidemia, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and peripheral arterial disease were more frequent in men, diabetes, left ventricular hypertrophy, and heart failure were more common in women. These differences observed between sexes are similar to those recently published from research in patients with acute coronary syndromes. 18 The presence of more cases of left ventricular hypertrophy and heart failure in women is consistent with the well‐known impact of diabetes on the development of cardiac hypertensive complications. 21 , 22 It is likely that sex differences in chemokine/cytokine markers of atherosclerosis may explain these differences. 23 Although previous studies have shown similar clinical profile differences between sexes, the slower rate of decline in smoking over the past decade in women may modify the risk profile of female patients in the future. 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 12 , 24

BP control is crucial to improve prognosis in patients with coronary heart disease. Although BP control is still far from optimal in Spain, in recent years it has markedly improved, from <20% to about 40%, not only in the primary care setting but in secondary care centers as well. 24 Notably, BP control has improved not only in the hypertensive general population but also in patients with coronary heart disease. 10 , 25 , 26 This improvement is due to many factors, the most important of which may be an increasing concern about the need for adequate BP control. In this survey, almost all patients were taking several antihypertensive drugs; β‐blockers were the most commonly prescribed drugs. However, as in the general hypertensive population, BP in men with hypertension and coronary heart disease was better controlled than in women. 27 The classes of antihypertensive agents significantly differed between sexes. It is likely that this dissimilar distribution in the antihypertensive drugs may, at least in part, play a role in degree of BP control. 7 , 28

Recent guidelines have also established a BP objective <130/80 mm Hg in hypertensive patients with diabetes and coronary heart disease. Thus, we analyzed the sample with this lower BP target. Our data again showed worse BP control in women despite that diabetes is more common in this population. In the multivariate analysis, sex was a predictor of poor BP control independently of the presence of diabetes.

Several studies have analyzed the lipid (LDL‐C) control rate in patients with coronary heart disease. These surveys have shown that not only in primary care but also in cardiology practices control is still far from optimal. 9 , 10 , 29 , 30 Our data show that although the majority of patients are taking lipid‐lowering drugs, fewer than a third of dyslipidemic patients have their LDL‐C controlled to goal levels. This situation is even worse in women and seems to be clearly related to less use of lipid‐lowering drugs in women. 12

Of interest, the prevalence of atrial fibrillation was more frequent in women; this may explain the higher use of anticoagulants in this population. However, since some patients with coronary heart disease and atrial fibrillation may benefit from dual treatment with antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants, the observed underuse of antiplatelets in women could be clinically relevant for cardiovascular outcomes. 2

To treat patients with ischemic heart disease adequately, it is necessary to use a correct diagnostic approach. Although the sensitivity and specificity of the different cardiac diagnostic methods are well defined in men, they are less well established in women. 8 , 31 In fact, women may have false‐positive results on exercise tests more frequently than men, and by contrast, negative electrocardiography results in women do not exclude ischemic heart disease. 8 Despite that women have a similar or slightly higher prevalence of angina, 32 this survey indicated that men were more likely to undergo stress tests and coronary angiography. As a result, coronary heart disease in hypertensive women may be underdiagnosed. 17 , 18 This might have relevant prognosis implications.

Limitations

The cross‐sectional design of the study was chosen to best represent the “real world” of clinical practice. Consequently, a large population of hypertensive patients recruited by consecutive sampling was included in the trial. This methodology has its limitations, since it reduces the level of control that can be exercised to reduce variation and bias. However, the large number of patients included and the nature of the end points measured, with no comparators under review, minimizes this theoretical limitation. Because our study was carried out in a population attended by cardiologists in Spain, the data could probably only be generalized to those countries with the same health care delivery and cardiovascular risk profile. Finally, menopause is one of the main conditions that raise the risk of developing ischemic heart disease in women through different mechanisms, such as an increase in systolic BP. The use of hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women could also have an influence on the results of the study; the prevalence of premenopausal women was only 6.5%.

Conclusions

The clinical profile of a hypertensive population with coronary heart disease treated by cardiologists differed between sexes. Coronary heart disease in women appeared to be undertreated and underdiagnosed, which may in part explain the poorer BP and LDL‐C control rates observed in this population. These results highlight the need for ongoing medical education to improve the recognition and management of coronary heart disease in women, with the goal of reducing cardiovascular risk.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to express their gratitude to all investigators who actively participated in this study. The present study was supported by an unrestricted grant provided by Recordati España S.L. All data have been recorded and analyzed independently to prevent bias.

References

- 1. Fox CS, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Temporal trends in coronary heart disease mortality and sudden cardiac death from 1950 to 1999. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;110:522–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mosca L, Banka CL, Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence‐based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. Circulation. 2007;115:1481–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li TY, Rana JS, Manson JE, et al. Obesity as compared with physical activity in predicting risk of coronary heart disease in women. Circulation. 2006;113:499–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mosca L, Linfante AH, Benjamin EJ, et al. National study of physician awareness and adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111:499–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mosca L, Appel LJ, Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence‐based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:900–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anguita M, Rodriguez M, Ojeda S, et al. Clinical outcome and reversibility of systolic dysfunction in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy due to hypertension and chronic heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2004;57:834–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2007;25:1105–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosendorff C, Black HR, Cannon CP, et al. Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2007;115:2761–2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. EUROASPIRE Study Group . EUROASPIRE. A European Society of Cardiology survey of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: principal results. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:1569–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. EUROASPIRE II Study Group . Lifestyle and risk factor management and use of drug therapies in coronary patients from 15 countries. Principle results from EUROASPIRE II Euro Heart Survey Programme. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:554–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boersma E, Keil U, De Bacquer D, et al. Blood pressure is insufficiently controlled in European patients with established coronary heart disease. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1831–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hippisley‐Cox J, Pringle M, Crown N, et al. Sex inequalities in ischaemic heart disease in general practice: cross sectional survey. BMJ. 2001;322:832–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. European Society of Hypertension‐European Society of Cardiology Guidelines Committee . 2003 European Society of Hypertension – European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1011–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) . Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barrios V, Escobar C, Calderon A, et al. Cardiovascular risk profile and risk stratification of the hypertensive population attended by general practitioners and specialists in Spain. The CONTROLRISK study. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21:479–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Ohman EM, et al. International prevalence, recognition, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2006;295:180–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Radovanovic D, Erne P, Urban P, et al. Gender differences in management and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: results on 20,290 patients from the AMIS Plus Registry. Heart. 2007;93:1369–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alfredsson J, Stenestrand U, Wallentin L, et al. Gender differences in management and outcome in non‐ST‐elevation acute coronary syndrome. Heart. 2007;93:1357–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferrer‐Hita JJ, Domínguez‐Rodríguez A, García‐González MJ, et al. Female gender is an independent predictor of in‐hospital mortality in patients with ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty. Med Intensiva. 2008;32:110–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Steg PG, Lopez‐Sendon J, Lopez de Sa E, et al. External validity of clinical trials in acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Conen D, Ridker PM, Mora S, et al. Blood pressure and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Women’s Health Study. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2937–2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schillaci G, Pirro M, Pucci G, et al. Different impact of the metabolic syndrome on left ventricular structure and function in hypertensive men and women. Hypertension. 2006;47:881–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leung J, Jayachandran M, Kendall‐Thomas J, et al. Pilot study of sex differences in chemokine/cytokine markers of atherosclerosis in humans. Gend Med. 2008;5:44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schnoll RA, Patterson F, Lerman C. Treating tobacco dependence in women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16:1211–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barrios V, Banegas JR, Ruilope LM, et al. Evolution of blood pressure control in Spain. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1975–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tranche S, Lopez I, Mostaza JM, et al. Control of coronary risk factors in secondary prevention: PRESENAP study. Med Clin. 2006;127:765–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Keyhani S, Scobie JV, Hebert PL, et al. Gender disparities in blood pressure control and cardiovascular care in a national sample of ambulatory care visits. Hypertension. 2008;51:1149–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ho PM, Magid DJ, Shetterly SM, et al. Medication nonadherence is associated with a broad range of adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2008;155:772–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. De Velasco JA, Cosin J, López‐Sendón JL, et al. New data on secondary prevention of myocardial infarction in Spain. Results of the PREVESE II study. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2002;55:601–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Qureshi AI, Suri MF, Guterman LR, et al. Ineffective secondary prevention in survivors of cardiovascular events in the US population. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1621–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Metz LD, Beattie M, Hom R, et al. The prognostic value of normal exercise myocardial perfusion imaging and exercise echocardiography: a meta‐analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hemingway H, Langenberg C, Damant J, et al. Prevalence of angina in women versus men: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of international variations across 31 countries. Circulation. 2008;117:1526–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]