Abstract

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:82–88. ©2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Arm size can affect the accuracy of blood pressure (BP) measurement, and “undercuffing” of large upper arms is likely to be a growing problem. Therefore, the authors investigated the relationship between upper arm and wrist readings. Upper arm and wrist circumferences and BP were measured in 261 consecutive patients. Upper arm auscultation and wrist BP was measured in triplicate, rotating measurements every 30 seconds between sites. Upper arm BP was 131.9±20.6/71.6±12.6 mm Hg in an obese population (body mass index, 30.6±6.6 kg/m2) with mean upper arm size of 30.7±5.1 cm. Wrist BP was higher (2.6±9.2 mm Hg and 4.9±6.6 mm Hg, respectively, P<.001); however, there was moderate concordance for the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) strata (κ value=0.27–0.71), and the difference was ≥5 mm Hg in 72% of the patients. The authors conclude that there was poor concordance between arm and wrist BP measurement and found no evidence that “hidden undercuffing” was associated with obesity; therefore, they do not support routine use of wrist BP measurements.

In clinical practice, blood pressure (BP) treatment decisions are based on noninvasive indirect measurements, but even though BP has been measured indirectly for more than 100 years, the methodology remains an area of debate and investigation. 1 , 2 Both the American Heart Association and the European Societies of Hypertension and Cardiology have published guidelines for the “optimal” methods and conditions for BP measurement, 3 , 4 , 5 and both recommend upper arm sphygmomanometry as the standard. As long ago as 1901, Von Recklinghausen recognized that variation in upper arm size is a potential source of significant error, so that it is important to match cuff size to upper arm circumference to avoid “undercuffing” (too small or narrow cuff bladder) of large arms that can lead to spuriously high readings. 6 , 7 , 8 Many studies have shown that miscuffing is extremely common in outpatient settings, and undercuffing may account for as much as 84% of the errors due to technical measurement innaccuracies. 9 Failure to recognize the need for a large cuff or the unavailability of a range of cuff sizes further complicates this issue. 10 Even with appropriate cuff sizes, it is possible that some degree of hidden undercuffing may occur. Hidden undercuffing is a term used to define inadvertent miscuffing or the dysfunction of an apparently appropriately sized cuff. In obese individuals, undercuffing may be hidden because of variations in arm shape/size and/or the increased amount of soft tissue that must be compressed to occlude the brachial artery. Brachial BP measurement is further complicated in obesity by the large circumference of the upper arm, which requires a very long, wide cuff for occlusion. In some cases, the excessive width of the required cuff can exceed the length of the upper arm, making it difficult to position the cuff to properly occlude the brachial artery. It is also possible that a larger than usual amount of pressure may be required to compress the greater amount of soft tissue in the obese arm. These limitations could produce systematically spuriously high BP values, producing a positive erroneous gradient between indirect vs true (ie, intra‐arterial) BP.

The increasing prevalence of obesity (and correspondingly larger arms) will likely lead to an increase in BP measurement errors. 7 , 8 Measuring BP at the wrist is an alternative, and several wrist devices have been validated according to published guidelines. However, use of wrist cuffs is still generally discouraged, 3 , 4 largely because of uncertainties related to their accuracy and the many (poorly described) factors that may produce different readings compared with the standard upper arm measurements. Given the problems with upper arm measurements in obese individuals and the likelihood that wrist size does not vary as much or increase to the same extent as upper arm sizes in obese individuals, it is possible that wrist measurements may be an acceptable alternative in that population. 7 , 8

In this study we aimed to explore whether hidden undercuffing occurs among obese patients by testing the hypothesis that wrist BP levels are systematically lower compared with upper arm readings among patients with larger upper arms. We propose that this would be the case because wrist BP would, in theory, remain relatively stable as the upper arm BP spuriously increased with progressively larger arm sizes. In addition, we sought to determine how well a validated wrist BP device can be used as an alternative to standard upper arm measurement in clinical practice and to explore some of the factors that could contribute to differences between BP values obtained at the two anatomical sites.

Methods

This study was approved by the University of Michigan Medical School Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research and conducted at the University of Michigan outpatient hypertension clinic. For all patients, arm and wrist circumferences, weight, height, current antihypertensive medications, lipoprotein and basic chemistry levels, diabetic status, and current smoking status (self‐reported) were recorded. Upper arm and wrist BP were obtained in 261 consecutive patients; inability to obtain BP at either site excluded a patient from participation. We followed a standardized protocol in which an appropriate‐sized cuff for upper arm size 3 (attached to aneroid monitor) was placed on the dominant arm and an oscillometric HoMedics BPW‐200 wrist cuff (HoMedics, Inc, Commerce Township, MI) was applied on the same arm. Patients then sat quietly alone for 5 minutes in a private room prior to BP measurement. One of 3 medical assistants trained in proper auscultatory measurement technique performed subsequent testing. Auscultatory upper arm BP and oscillometric wrist BP were measured with the elbow supported at heart level (approximately the 3rd–4th intercostal space) Measurements were performed every 30 seconds, alternating between the two sites, randomly starting with either the wrist or arm. A total of 3 wrist and 3 upper arm BP levels were obtained. The mean of these values for each site was used as the primary outcome.

All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to compare the mean of the 3 systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) measurements obtained at the wrist and arm. Differences between mean SBP and DBP measured at the arm and wrist were compared using paired t tests, linear regression, and Bland–Altman plots. 11 Concordance between arm and wrist BP was assessed across different Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) strata using the κ coefficient. 12 , 13 The differences in the wrist and arm mean SBP and DBP (ΔBP values) were correlated with arm and wrist sizes and their difference (Δcircumference). Multiple linear regression models with different clinical parameters were analyzed to assess the determinants of the differences between BP levels (ΔBP) obtained at the arm and wrist. All results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was accepted at the P≤.05 level.

Results

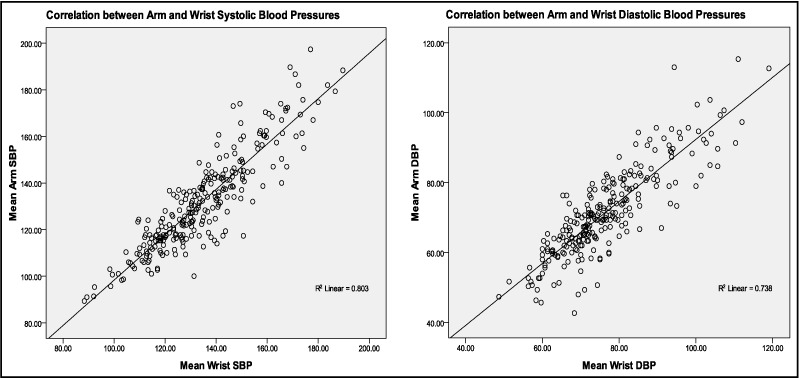

Table I shows the demographic, anthropometric, BP, and measured clinical characteristics of the 261 patients included in this study. Mean wrist BP was higher than arm BP for both SBP (2.6±9.2 mm Hg, P<.001, wrist – arm) and DBP (4.9±6.6 mm Hg, P<.001) in the entire patient cohort. A high degree of correlation was observed between both mean arm and wrist SBP and DBP (Figure 1). Correlation coefficients for arm and wrist SBP and DBP were 0.896 and 0.859, respectively (both P<.001).

Table I.

Patient Demographics (N=261)

| Mean (±SD) or No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 62.1±14.6 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 134 (51.3%) |

| Female | 127 (48.6%) |

| Anthropometrics | |

| Height, cm | 168.7±10.1 |

| Weight, kg | 87.9±23.7 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 30.6±6.6 |

| Arm size, cm | 30.7±5.1 |

| Wrist size, cm | 17.1±2.3 |

| BPs, mm Hg | |

| Brachial SBP | 131.9±20.6 |

| Brachial DBP | 71.6±12.6 |

| Wrist SBP | 134.6±19.0 |

| Wrist DBP | 76.6±12.2 |

| Lipid profile, mg/dL | |

| Total cholesterol | 183.5±44.1 |

| HDL‐C | 48.6±16.8 |

| LDL‐C | 105.3±38.2 |

| Triglycerides | 150.6±98.9 |

| Smokers | 52 (19.9%) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 181 (69.3%) |

| Number of BP medications | 3.36±1.6 |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic BP; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein; SBP, systolic BP.

Figure 1.

Correlation between arm and wrist systolic blood pressure (SBP) (left panel) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (right panel) values.

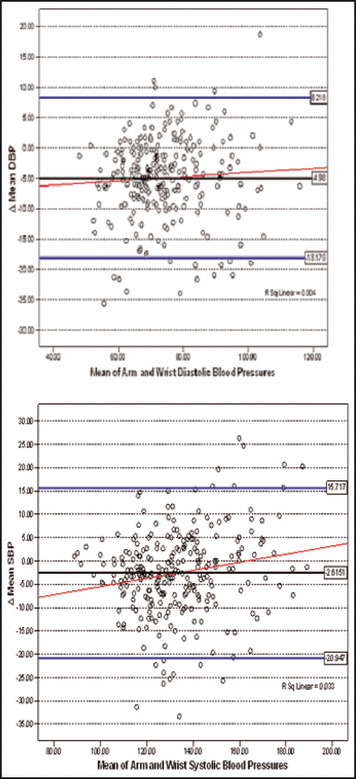

Despite the strong correlations, the majority of patients had SBP or DBP absolute differences of ≥5 mm Hg between the two methods, and approximately one third had a difference of ≥10 mm Hg in SBP or DBP (Table II). Bland–Altman plots for SBP and DBP illustrate the wide variability among the specific individuals in BP values obtained at the upper arm vs the wrist (Figure 2). Estimates of the ±2 SD range for SBP were +15.7 mm Hg to −20.9 mm Hg about the mean and for DBP ±2 SD extended from +8.2 to −18.1 mm Hg.

Table II.

Number of Patients with Absolute Differences of ≥5 and ≥10 mm Hg SBP and DBP Measured at the Arm and Wrist

| category | ΔBP ≥5 mm hg | ΔBP ≥10 mm hg |

| SBP | 139 (53%) | 65 (25%) |

| DBP | 139 (53%) | 50 (19%) |

| Either SBP or DBP | 187 (72%) | 91 (35%) |

Abbreviations: ΔBP, absolute difference of mean blood pressures measured at arm and wrist; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Figure 2.

Bland–Altman Plots for means of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) as measured at the arm and wrist against the difference between the two measures (Δ). The limits of agreement (±2 standard deviation) are presented by the two blue lines while the red lines represent the regression lines.

The κ statistic 13 calculated for each JNC 7 stratum showed poor agreement for both SBP and DBP for placing individual patients into the same BP category based on the wrist vs arm BP values (Table III). This lack of agreement between arm and wrist BP indicates that substituting wrist BP for arm values often leads to erroneous classification of BP status (and hypertension status), which could affect the type of therapeutic intervention recommended clinically.

Table III.

Agreement of Measurements Obtained at Arm and Wrist Across JNC 7 Strata

| Risk Category for DBP | Arm DBP No. (%) | Wrist DBP No. (%) | κ (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 200 (77) | 176 (67) | 0.651 (0.55, 0.751) |

| Pre‐HTN | 34 (13) | 46 (18) | 0.353 (0.203, 0.504) |

| HTN stage 1 | 21 (8) | 22 (8) | 0.266 (0.17,0.563) |

| HTN stage 2 | 6 (2) | 17 (7) | 0.415 (0.161,0.669) |

| Risk category for SBP | |||

| Normal | 86 (33) | 62 (24) | 0.64 (0.543, 0.746) |

| Pre‐HTN | 93 (36) | 101 (39) | 0.443 (0.331, 0.555) |

| HTN stage 1 | 49 (19) | 69 (26) | 0.414 (0.286,0.541) |

| HTN stage 2 | 33 (13) | 29 (11) | 0.707 (0.572,0.842) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HTN, hypertension; JNC 7, Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

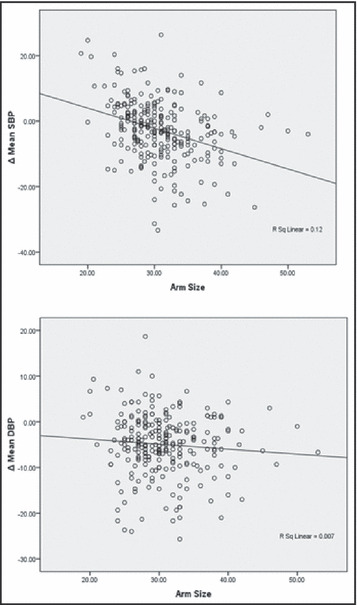

The relationship between arm size and ΔBP values measured at the arm and the wrist is shown in Figure 3. There were inverse correlations for ΔSBP with both wrist and arm sizes, and contrary to our original speculation, a larger upper arm compared with wrist size (arm – wrist circumference) was also negatively correlated (Table IV). This means that patients with larger upper arms (or larger arms compared with wrists) tended to have higher wrist compared with arm BP levels. For those with largest arm sizes (≥35 cm), mean ΔBP values were −6.9±8.1 mm Hg and −5.2±5.9 mm Hg for SBP and DBP, respectively. For DBP, wrist size was inversely correlated with ΔDBP, but arm size and the arm minus wrist difference were not. Other clinical parameters that were significantly correlated with the differences between arm and wrist SBP and DBP values are presented in Table IV.

Figure 3.

Relationship between upper arm size (cm) to the difference in mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) measured at the arm and wrist (arm – wrist, mm Hg).

Table IV.

Predictors of the Difference Between Arm and Wrist SBP and DBP Values

| correlation coefficient (pearson) | p value (2‐tailed) | |

| Parameter (for Δmean SBP) | ||

| Age | 0.217 | <.001 |

| Female sex | 0.292 | <.001 |

| HDL‐C | 0.184 | .004 |

| Arm size | −0.347 | <.001 |

| Wrist size | −0.333 | <.001 |

| Arm – wrist size | −0.257 | <.001 |

| Body mass index | −0.362 | <.001 |

| Mean arm SBP | 0.393 | <.001 |

| Parameter (for Δmean DBP) | ||

| Mean arm SBP | 0.153 | .013 |

| Mean arm DBP | 0.322 | <.001 |

| Mean wrist SBP | −0.327 | <.001 |

| Female sex | 0.140 | .023 |

| GFR | 0.219 | .001 |

| Wrist size | −0.139 | .025 |

| Age | −0.173 | .005 |

| No. of BP medications | −0.161 | .009 |

Abbreviations: Δmean, absolute difference of mean blood pressures measured at arm and wrist; BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic BP; GFR, glomerular filtration rate, SBP, systolic BP.

Linear regression models were constructed to explain the differences between the SBP and DBP (with ΔBP values as the dependent variables) measured at the arm and the wrist with the data from Table IV. No overall model could explain more than a small fraction (R 2=0.096–0.098) of the differences (data not shown). Arm sizes remained significant predictors of the SBP gradient in multivariate models.

Discussion

The main finding of this analysis is that although they are strongly correlated, there can be considerable discordance between wrist and arm BP values. We show here that even when a carefully standardized measurement protocol is followed and a single validated wrist monitor utilized, many patients have BP readings of 5 or 10 mm Hg or more between sites, which would lead to substantial differences in the categorization into BP strata using the limits specified by JNC 7. 12 Because arm measurements have been used almost exclusively in epidemiologic and clinical trials, 12 and because the BP difference between arm and wrist is poorly predicted by commonly available clinical variables (R 2<0.10), our results suggest that wrist BP should not routinely substitute for arm readings in clinical practice.

Concordance Between Wrist and Upper Arm BP

In the past few years, several wrist devices have been evaluated for validity and the accuracy of measurements. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 Many of these studies have validated different wrist devices as being accurate for measuring BP in different populations according to the standards prescribed by the American Association for Medical Instrumentation 19 and the British Hypertension Society Working Party on Blood Pressure Measurement Standards. 4 In the present study, we were not attempting to validate the “accuracy” of a particular wrist BP monitor model, which passed the previous testing 19 required for it to be available commercially in the United States. Our study was intended to address an issue of potential clinical importance in light of the increasing prevalence of obesity. 7 , 8

The issue of whether arm and wrist BP are comparable has been addressed in a few studies. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 24 , 25 Latman and colleagues 14 concluded that there are significant measurement errors associated with wrist devices, which Mourad and colleagues 16 attributed to uncertainty of the wrist position (perhaps reflecting a lack of standardization in the protocol). Cuckson and colleagues 15 recommended wrist BP levels as an acceptable surrogate for home BP measurements despite noting that the particular wrist device used in their study was not well validated. 4 , 15 , 18 , 19

As demonstrated in our study, however, even when a validated device is employed in a standardized protocol, important differences may still exist for SBP and DBP measured at the arm and the wrist. In the entire population, the large differences in readings (high and low) tend to cancel each other out, leading to a relative small mean difference, and there was reasonably good correlation between the two readings. However, these statistical parameters do not adequately convey the true magnitude of variation between readings in specific individuals. Our results demonstrate that the SD values for the differences within individuals (Figure 2) were large and resulted in significant discordance (Table III) and poor agreement (Table II) when classifying patients by JNC 7 BP strata (Table III). 12

A recent study by Stergiou and colleagues 25 evaluating home wrist and arm BP in 79 patients reported similar discordance between BP readings obtained at the different sites. The authors concluded that, similar to our findings, important differences may exist between BP levels determined at arm and wrist sites even when meticulous methods are used.

Thus, despite the growing popularity of wrist devices, caution needs to be exercised before their introduction into routine clinical practice, and our results support the recommendation that a validated upper arm device with an appropriately sized cuff should remain the standard of practice for measuring BP, even among patients with very large arms. However, if a wrist device is needed (eg, when upper arm measurement is painful), then the concordance of wrist and upper arm values should be documented. We emphasize that the demonstration device accuracy within a population are not enough to assure that it provides “accurate” BP readings in every individual. Contrary to our initial speculation, we observed that wrist BP values were generally higher than arm BP levels (Table I and Figure 2), and the mean ΔSBP (arm – wrist) was inversely related to arm circumference (Figure 3 and Table IV). The higher wrist BP level was particularly accentuated among individuals who would normally use a large adult or thigh cuff (ie, arm circumference >35 cm). The observation that patients with larger upper arms tended to have higher wrist vs arm BP values is contrary to our hypothesis and does not support the theory of hidden undercuffing. We note that our findings differ from those of Stergiou and colleagues, who did not find a significant association between arm sizes and the BP gradients. Their sample size was smaller and they measured arm and wrist BP on different days (not sequentially as in the present protocol).

Although we believe that our conclusions that wrist BP is not a suitable substitute for arm BP in many individuals and that there is no evidence of systematic undercuffing in our population, we note that we do not know that the specific wrist device we used was accurate or that the systematic differences were the product of the algorithm used by the device. It is possible that these results would not be replicated if another device were used, but only a systematic study comparing intra‐arterial BP readings with indirectly measured arm BP and multiple different wrist monitors could definitively corroborate our conclusions. Nonetheless, the device utilized has proven acceptably accurate in previous validation studies, and it provided readings that were highly correlated with arm BP values. Given that we used the same monitor in all individuals and standardized our BP measurement protocol, we believe that our findings are correct.

Conclusions

As far as we are aware, this is the largest study to assess the effect of arm size and other factors on the difference between wrist and upper arm BP. 24 , 25 This is also the first report to specifically investigate whether hidden undercuffing is occurring among obese patients when upper arm BP is measured according to current guidelines. 3 Our findings suggest that using wrist BP measurements to guide clinical decision‐making in an individual hypertensive requires at a minimum that arm and wrist BP be compared and demonstrated to be concordant. Our findings strongly support current recommendations that arm BP be used whenever feasible, even in obese individuals, and we did not see effects of hidden undercuffing in obese patients.

References

- 1. Korotkoff NC. To the question of methods of determining the blood pressure (from the clinic of Professor C P Federoff). Reports of the Imperial Military Academy. 1905;11:365–367. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Korotkoff NC. Contribution to the methods of measuring blood pressure; second preliminary report 13 December 1905. Vrachebnaya Gazeta. 1906;10:278. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals, 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2005;45:142–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O’Brien E, Waeber B, Parati G, et al. Blood pressure measuring devices: recommendations of the European Society of Hypertension. BMJ. 2001;322:531–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mancia G, De Backer MG, Dominiczak A, et al. Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension; European Society of Cardiology . 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2007;25:1105–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Von Recklinghausen H. Ueber blutdrukmessung Beim menschen. Arch Exper Path u Pharmakol. 1901;46:78–132. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Graves JW, Darby CH, Bailey K, et al. The changing prevalence of arm circumferences in NHANES III and NHANES 2000 and its impact on the utility of the “standard adult” blood pressure cuff. Blood Press Monit. 2003;8:223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O’Brien E, Atkins N, O’Malley K. Selecting the correct bladder according to distribution of arm circumference in the population. Hypertension. 1993;11:1149–1150. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manning DM, Kuchirka C, Kaminski J. Miscuffing: inappropriate blood pressure cuff application. Circulation. 1983;68:763–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thomas M, Radford T, Dasgupta I. Unvalidated blood pressure devices with small cuffs are being used in hospitals. BMJ. 2001;323:398. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bland JM, Altman DG. Comparing methods of measurement: why plotting difference against standard method is misleading. Lancet. 1995;346:1085–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chobanian A, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. The JNC7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McGinn T, Wyer PC et al. Tips for learners of evidence‐based medicine: 3. Measures of observer variability (kappa statistic). CMAJ. 2004;171:1369–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Latman NS, Latman A. Evaluation of instruments for noninvasive blood pressure monitoring of the wrist. Biomed Instrum Technol. 1997;31:63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cuckson AC, Moran P, Seed P, et al. Clinical evaluation of an automated oscillometric blood pressure wrist device. Blood Press Monit. 2004;9:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mourad A, Gillies A, Carney S. Inaccuracy of wrist‐cuff oscillometric blood pressure devices: an arm position artifact? Blood Press Monit. 2005;10:67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Uen S, Weisser B, Wieneke P, et al. Evaluation of the performance of a wrist blood pressure measuring device with a position sensor compared to ambulatory 24‐hour blood pressure measurements. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:787–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. O’Brien E, Petrie J, Littler W, et al. The British Hypertension Society protocol for the evaluation of blood pressure measuring devices. J Hypertens. 1993;11(suppl 2):S43–S62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation . American National Standard. Electronic or Automated Sphygmomanometers. ANSI/AAMI SP 10‐1992. Arlington, VA: AAMI, 1993:40 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Altunkan S, Oztas K, Altunkan E. Validation of the Omron 637IT wrist blood pressure measuring device with a position sensor according to the International Protocol in adults and obese adults. Blood Press Monit. 2006;11:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Altunkan S, Ilman N, Altunkan E. Validation of the Samsung SBM‐100A and Microlife BP 3BU1‐5 wrist blood pressure measuring devices in adults according to the International Protocol. Blood Press Monit. 2007;12:119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Altunkan S, Yildiz S, Azer S. Wrist blood pressure‐measuring devices: a comparative study of accuracy with a standard auscultatory method using a mercury manometer. Blood Press Monit. 2002;7:281–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rogers P, Burke V, Stroud P, et al. Comparison of oscillometric blood pressure measurements at the wrist with an upper‐arm auscultatory mercury sphygmomanometer. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1999;26:477–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chell K, Bradley E, Bucher L, et al. Clinical comparison of automatic, noninvasive measurement of blood pressure in the forearm and upper arm. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14:232–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stergiou GS, Christodoulakis GR, Nasothimiou EG, et al. Can validated wrist devices with position sensors replace arm devices for self‐home blood pressure monitoring? A randomized crossover trial using ambulatory monitoring as a reference. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]