Abstract

We have designed a universal PCR capable of amplifying a portion of the 16S rRNA gene of eubacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecium, Enterococcus faecalis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Legionella pneumophila, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Serratia marcescens, Enterobacter cloacae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, Proteus mirabilis, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria meningitidis. The sizes of the amplified products from various bacteria were the same (996 bp), but the restriction patterns of most PCR products generated by HaeIII digestion were different. PCR products from S. aureus and S. epidermidis could not be digested by HaeIII but yielded different patterns when they were digested with MnlI. PCR products from S. pneumoniae, E. faecium, and E. faecalis yielded the same HaeIII digestion pattern but could be differentiated by AluI digestion. PCR products from E. coli, K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, and E. cloacae also had the same HaeIII digestion pattern but had different patterns when digested with DdeI or BstBI. This universal PCR could detect as few as 10 E. coli or 250 S. aureus organisms. Compared with culture, the sensitivity of this universal PCR for detection and identification of bacteria directly from 150 cerebrospinal fluids was 92.3%. These results suggest that this universal PCR coupled with restriction enzyme analysis can be used to detect and identify bacterial pathogens in clinical specimens.

Rapid detection and identification of bacteria in blood and cerebrospinal fluids (CSF) is crucial in patient management because the mortality rate associated with infections in the bloodstream or central nervous system is very high (9, 13, 14). Among the various methods currently used in clinical laboratories for detection of bacterial infections, culture is the most sensitive one. However, culture requires at least 8 h of incubation. Additional time is needed to perform biochemical or immunological tests to identify the bacteria.

The main goal of this study is to develop an alternative method for detection and identification of bacteria in body fluids, such as blood and CSF. Since the 16S rRNA genes of almost all common bacterial pathogens found in body fluids have been sequenced, it is possible to design PCR primers capable of amplifying all eubacteria based on the conservative nature of the 16S rRNA genes (3, 10). We have designed one set of such primers and found that this universal PCR can amplify all bacteria that we have examined to date. We have also found that restriction enzyme digestion patterns of the universal primer PCR products from different species of bacteria are different. The results of this study indicate that this universal PCR followed by restriction enzyme analysis is useful for rapid detection and identification of bacterial pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The following bacteria were used as controls: Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 12228, Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC 19615, Streptococcus agalactiae ATCC 13813, Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 6301, Enterococcus faecium ATCC 19434, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Mycobacterium tuberculosis ATCC 25618, Legionella pneumophila ATCC 33152, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883, Serratia marcescens ATCC 14764, Enterobacter cloacae ATCC 23355, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 25668, Acinetobacter baumannii, Proteus mirabilis ATCC 10005, Haemophilus influenzae ATCC 35056, and Neisseria meningitidis ATCC 10377. Many isolates of each of the above bacteria were obtained from the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, Tri-Service General Hospital (TSGH), Taipei, Taiwan, and other hospitals in Taiwan.

Preparation of samples for PCR analysis.

Bacterial lysates were used for PCR. Approximately 105 CFU of bacteria were washed in 1 ml of a lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), and 1 mM EDTA and then pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 5 min. Each pellet was suspended in 100 μl of the same lysis buffer and then boiled in a water bath for 30 min to release the DNA. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was saved for PCR. To perform PCR on CSF specimens, 500 μl of CSF was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in 180 μl of sterile distilled water, and the DNA was purified with the QIAamp Tissue Kit (QIAGEN Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.) according to the procedures provided by the manufacturer.

Clinical specimens.

From April 1997 to May 1999, 150 CSF specimens were obtained from 150 different patients in the TSGH. These specimens were examined for the presence of bacteria by both culture and the universal PCR developed in this study. Thirteen of the 150 CSF specimens were positive by bacterial culture. Laboratory parameters of these 13 patients are shown in Table 1. CSF specimens from patients with bacterial meningitis usually have a decreased sugar concentration and an increased protein concentration. Although every CSF specimen had an elevated white blood cell count, sugar and protein levels were not completely consistent with the presence or absence of bacteria determined by culture or PCR.

TABLE 1.

Laboratory parameters of patients with bacterial meningitis

| Patient no. | Sex | Age (yr) | Bacterium identified | Glucose (mg/liter) | Protein (mg/liter) | WBCa (cells/μl) | CSF bacterial cultureb | CSF universal PCRb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 3 | E. coli | 5 | 2,835 | 1,100 | + | + |

| 2 | M | 72 | A. baumannii | 20 | 8,650 | 15,000 | + | − |

| 3 | M | 82 | P. mirabilis | 102 | 114 | 300 | + | + |

| 4 | F | 74 | S. aureus | 10 | 126 | 900 | + | + |

| 5 | M | 65 | S. epidermidis | 74 | 162 | 540 | + | + |

| 6 | M | 62 | S. aureus | 41 | 95 | 220 | + | + |

| 7 | M | 68 | M. tuberculosis | 3.2 | 276 | 200 | + | + |

| 8 | M | 3 | Group B streptococcus | 10 | 1,165 | 1,890 | + | + |

| 9 | M | 5 | H. influenzae | 15 | 184 | 270 | −c | + |

| 10 | M | 1 | P. mirabilis | 41 | 117 | 3,000 | + | + |

| 11 | M | 3 | H. influenzae | <10 | 900 | 2,400 | + | + |

| 12 | M | 1 | Group B streptococcus | 10 | 1,800 | 2,500 | −c | + |

| 13 | M | 3 | S. pneumoniae | 10 | 843 | 1740 | − | + |

| 14 | M | 3 | P. aeruginosa | 21 | 237 | 150 | + | + |

| 15 | F | 83 | M. tuberculosis | 79 | 175 | 200 | + | + |

| 16 | F | 64 | P. aeruginosa | 71 | 125 | 3,600 | + | + |

WBC, white blood cells.

+, positive result; −, negative result.

Positive bacterial antigen assay for H. influenzae type b or group B streptococcus, respectively.

PCR amplification.

A reaction mixture containing approximately 50 ng of template DNA, PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3; 50 mM KCl; 2.5 mM MgCl2; 0.001% gelatin), a 0.2 μM concentration of each PCR primer, a 0.2 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.) in a total volume of 50 μl was prepared. After a 10-min denaturation at 94°C, the reaction mixture was run through 35 cycles of denaturation for 1 min at 94°C, annealing for 1 min at 55°C, and extension for 2 min at 72°C, followed by an incubation for 10 min at 72°C. Five microliters of PCR product was electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel to determine the size of the product. Both negative and reagent controls were included in each PCR run. The reagent control consisted of all PCR components except for the template DNA. If either control became positive, the entire PCR was repeated. Restriction enzyme analysis was also performed on PCR products to detect contamination. If the digestion patterns from different PCR products were the same, the samples were suspected to have been contaminated. The PCR was repeated.

Restriction endonuclease digestions.

Five microliters of each PCR product was digested with different restriction enzymes in appropriate restriction enzyme buffer in a total volume of 20 μl. After incubation for 2 h at the recommended temperature, the digested DNA was electrophoresed on a 6% polyacrylamide gel.

RESULTS

To develop a PCR capable of amplifying all bacteria, nucleotide sequences of the 16S rRNA genes of common pathogenic bacteria, including S. aureus, S. pyogenes, S. agalactiae, S. pneumoniae, E. faecium, M. tuberculosis, L. pneumophila, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, P. aeruginosa, P. mirabilis, H. influenzae, and N. meningitidis, were compared. One pair of primers, designated U1 and U2, with sequences conserved among all of these bacteria was selected. The sequence of primer U1 is 5′-CCAGCAGCCGCGGTAATACG-3′, corresponding to nucleotides 518 to 537 of the E. coli 16S rRNA gene, and that of U2 is 5′-ATCGG(C/T)TACCTTGTTACGACTTC-3′, corresponding to nucleotides 1513 to 1491 of the same gene. PCR performed with these two primers is referred to as the universal PCR in this study.

DNAs from the American Type Culture Collection control bacteria were examined by the universal PCR. All of these DNA samples generated a PCR product of the expected size (996 bp). A nonspecific band of approximately 150 bp was also produced.

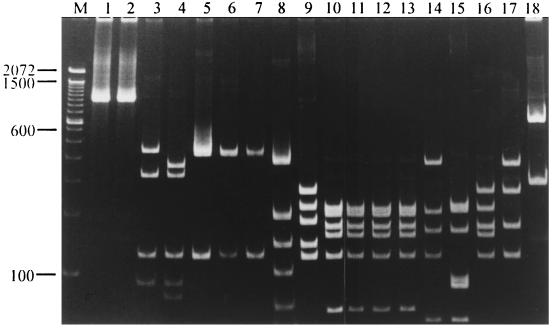

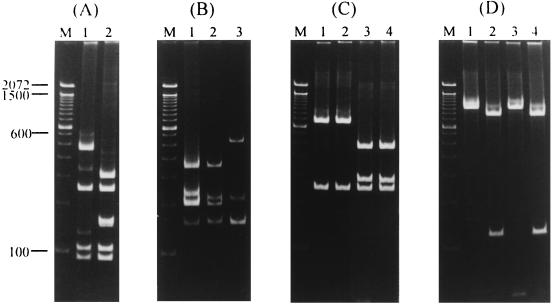

The PCR products were then digested with HaeIII to determine whether there is a restriction fragment length polymorphism that can be used to identify certain bacteria. All PCR products, except for those of S. aureus and S. epidermidis, were digested into several fragments (Fig. 1). The PCR products from S. aureus and S. epidermidis gave rise to different patterns when they were digested with MnlI (Fig. 2A). PCR products from S. pneumoniae, E. faecium, and E. faecalis had the same HaeIII digestion patterns but had different AluI digestion patterns (Fig. 2B). PCR products from E. coli, K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, and E. cloacae also generated the same HaeIII digestion pattern but yielded different patterns when they were digested with DdeI (Fig. 2C) or BstBI (Fig. 2D). Digestion of the PCR products with DdeI produced two different patterns: those of E. coli and K. pneumoniae yielded one pattern (two fragments, 757 and 239 bp), and those from S. marcescens and E. cloacae yielded the other (three fragments, 474, 283, and 239 bp) (Fig. 2C). PCR products from E. coli and S. marcescens could not be digested by BstBI, whereas those from K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae were digested into two fragments (876 and 120 bp) (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 1.

HaeIII digestion patterns of universal PCR products. Samples in different lanes were HaeIII-digested PCR products from the following bacteria: lane 1, S. aureus; lane 2, S. epidermidis; lane 3, S. pyogenes; lane 4, S. agalactiae; lane 5, S. pneumoniae; lane 6, E. faecium; lane 7, E. faecalis; lane 8, M. tuberculosis; lane 9, L. pneumophila; lane 10, E. coli; lane 11, K. pneumoniae; lane 12, S. marcescens; lane 13, E. cloacae; lane 14, P. aeruginosa; lane 15, A. baumannii; lane 16, P. mirabilis; lane 17, H. influenzae; lane 18, N. meningitidis. Lane M contained molecular size standards (base pairs). The sizes of the molecular size standards are marked on the left of the gel.

FIG. 2.

Restriction digestion patterns of the universal PCR products. (A) MnlI digestion patterns of the universal PCR products from S. aureus (lane 1) and S. epidermidis (lane 2). (B) AluI digestion patterns of the universal PCR products from S. pneumoniae (lane 1), E. faecium (lane 2), and E. faecalis (lane 3). (C) DdeI digestion patterns of the universal PCR products from E. coli (lane 1), K. pneumoniae (lane 2), S. marcescens (lane 3), and E. cloacae (lane 4). (D) BstBI digestion patterns of the universal PCR products from E. coli (lane 1), K. pneumoniae (lane 2), S. marcescens (lane 3), and E. cloacae (lane 4). Lanes M are the same as in Fig. 1.

To determine whether PCR products from different isolates of one species of bacteria have the same restriction fragment length polymorphism pattern, 49 isolates of E. coli, 48 isolates of S. pyogenes, 46 isolates of L. pneumophila, 41 isolates of S. agalactiae, 16 isolates of S. pneumoniae, and 3 isolates each of S. aureus, S. epidermidis, M. tuberculosis, K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, E. cloacae, P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, P. mirabilis, H. influenzae, and N. meningitidis were examined. The same HaeIII digestion pattern was observed in PCR products from different isolates of one species of bacteria.

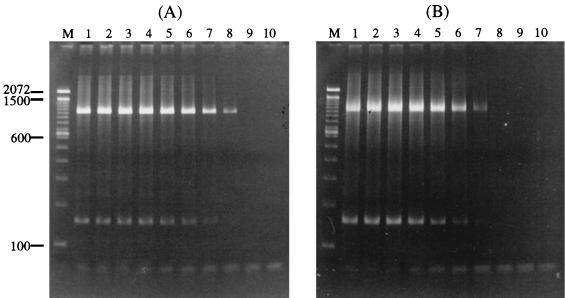

To determine the sensitivity of this universal PCR, E. coli ATCC 25922 and S. aureus ATCC 25923 cultures were serially diluted in a CSF sample that was confirmed to be PCR negative. An aliquot of each dilution was subjected to DNA isolation, and the purified DNA was used as the template for the PCR. The end point of the universal PCR for E. coli DNA was found to be approximately 10 organisms (Fig. 3A). The sensitivity for detection of S. aureus was determined to be approximately 250 organisms (Fig. 3B). These experiments were repeated three times, and the results from all three runs were the same.

FIG. 3.

Determination of the sensitivity of the universal PCR. Serial 10-fold dilutions of E. coli and S. aureus samples were amplified with the universal PCR, and the PCR products were electrophoresed on an agarose gel. (A) PCR results with E. coli DNA from 108 to <10 organisms (lanes 1 to 9) and no bacteria (lane 10). (B) PCR results with S. aureus from 2.5 × 107 to <10 organisms (lanes 1 to 9) and no bacteria (lane 10). Molecular marker sizes (lanes M) are given in base pairs on the left side of the picture. A band of approximately 150 bp is also seen in lanes that have the 996-bp PCR product; this band may be the result of nonspecific amplifications. Another band of approximately 50 bp is also present in some lanes with the intensity inversely proportional to the number of bacteria used for the PCR; this band is the primer dimer that formed during the PCR.

The universal PCR was then applied to 150 CSF specimens. Thirteen of these specimens were positive in culture (Table 1). All but one of these 13 CSF specimens generated positive PCR results. These 12 PCR products were digested with HaeIII, and the HaeIII digestion patterns were found to be identical to those of the bacteria isolated from these CSF specimens. These bacteria include two isolates each of P. mirabilis, P. aeruginosa, M. tuberculosis, and S. aureus and one isolate each of E. coli, group B streptococci, H. influenzae, and S. epidermidis. Of the remaining 137 culture-negative CSF specimens, three produced a positive PCR result, and the products were determined to be from group B streptococci, H. influenzae, and S. pneumoniae, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The main goal of this study was to develop a rapid and sensitive method to detect and identify bacteria in CSF specimens that are supposed to be sterile. A decision was made to use the PCR approach, and one set of PCR primers was designed based on the conserved sequence of the 16S rRNA genes of various bacteria. The universal PCR products from different bacteria were found to have different restriction patterns. In addition, PCR products from different isolates of the same bacteria were found to have the same restriction pattern. These results formed the basis for identification of bacteria in this study.

The use of a universal PCR that amplifies conserved regions in various bacteria for DNA sequencing or probe preparation has been described (1, 7, 10, 15). In 1989, Bottger (1) first demonstrated that a portion of the 16S rRNA gene from L. pneumophila, E. coli, or M. tuberculosis can be amplified by using one set of universal PCR primers and then sequenced to identify these bacteria. Greisen et al. (3) used two different sets (RW01-DG74 and RDR080-DG74) of universal primers to detect bacteria. With primers RW01 and DG74, DNA samples from 90 of 102 different bacterial species were amplified. The remaining 12 samples were amplified with primers RDR080 and DG74. Many different oligonucleotide probes were used to identify bacteria, including various probes specific for gram-positive or gram-negative bacteria and 13 different species-specific probes. Radstrom et al. (10) described the use of a seminested PCR method with genus- or species-specific primers to detect and identify H. influenzae, N. meningitidis, S. pneumoniae, S. agalactiae, and 24 different species of bacteria. All of these studies used multiple sets of PCR primers to detect or identify bacteria. In this study, we detected bacteria with only one set of PCR primers and used restriction enzyme analysis, instead of species-specific probes or sequencing, to identify bacteria. Twelve of the 13 bacterial culture- or antigen-positive CSF specimens were positive by the universal PCR; therefore, the sensitivity of this universal PCR is 92.3% (12 of 13).

One CSF specimen which grew A. baumannii was negative by the universal PCR. This specimen had an elevated leukocyte count (15,000 × 106 cells/liter) and protein level (8,650 mg/liter). This high protein level may be the cause of this false-negative PCR; therefore, it is recommended that an internal PCR control, which amplifies a housekeeping gene, e.g., the β-actin gene, be incorporated as part of the universal PCR. A false-positive PCR may also occur if the specimen is contaminated. This situation occurred most often when the PCR was performed by individuals with less laboratory experience. Contamination may come from previous PCR products or bacteria that are present in test tubes or reagents.

We also found three PCR-positive, culture-negative CSF specimens. One specimen was negative by Gram staining, bacterial antigen assay, and culture, but the patient had symptoms of bacterial meningitis and was responsive to antibiotic therapy. The other two specimens were found to be positive in bacterial antigen assays. Similar results have also been reported by Kristiansen et al. (6) and Cherian et al. (2), suggesting that PCR assay is useful for the early diagnosis of bacterial meningitis.

Our universal PCR was determined to have a sensitivity of 10 gram-negative bacteria (e.g., E. coli) and 250 gram-positive bacteria (e.g., S. aureus). Therefore, it would be adequate for detection of bacteria in CSF specimens, since 85% of CSF samples with bacterial infection contained more than 103 CFU of bacteria/ml (8). Although detection of bacterial pathogens in serum or whole blood by PCR has been reported (5, 12, 16), the universal PCR developed in this study may not have sufficient sensitivity for blood specimens, because the number of organisms in the blood is usually quite low. In one study, 25% of patients with S. aureus bacteremia and more than 50% with E. coli and P. aeruginosa bacteremia had colony counts of <1 CFU/ml of blood (4). There are also substances in the blood that may inhibit PCR assays. Improvements are needed to make our universal PCR useful for detection and identification of bacteria in the blood. The reason why the universal PCR had a lower sensitivity on gram-positive bacteria could be due to incomplete lysis of bacteria during DNA purification, since the cell wall of gram-positive bacteria is harder to dissolve than that of gram-negative bacteria.

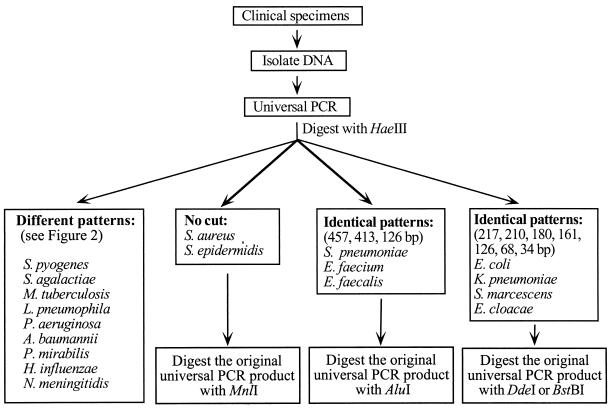

The procedures for the use of PCR-RFLP for detection and identification of bacterial pathogens are summarized in Fig. 4. This method requires only 1 day to complete. Conventional methods for detection and identification of bacterial pathogens require at least 2 days. Although automated or semiautomated blood culture systems can shorten the detection time from 1 day to several hours, an additional 1 to 2 days is required to identify the organisms. The universal PCR method will provide physicians with results at least 1 day earlier than conventional methods. Although the cost of using the universal primer PCR for diagnosis is higher than the conventional methods, the universal primer PCR coupled with restriction enzyme analysis can rapidly detect and identify pathogens so that the unnecessary use of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapies can be minimized. The positive impact in patient care with the use of the universal primer PCR for diagnosis would be significant.

FIG. 4.

Flow chart of the universal PCR and RFLP for detection and identification of common bacterial pathogens in body fluids.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants TSGH-C86-47 from the TSGH and NSC87-2312-B-016-002 and NSC88-2314-B-016-005 from the National Science Council, Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bottger E C. Rapid determination of bacterial ribosomal RNA sequences by direct sequencing of enzymatically amplified DNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;65:171–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(89)90386-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherian T, Lalitha M K, Manoharan A, Thomas K, Yolken R H, Steinhoff M C. PCR-enzyme immunoassay for detection of Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA in cerebrospinal fluid samples from patients with culture-negative meningitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3605–3608. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3605-3608.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greisen K, Loeffelholz M, Purohit A, Leong D. PCR primers and probes for the 16S rRNA gene of most species of pathogenic bacteria, including bacteria found in cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:335–351. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.335-351.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henry N K, McLimans C A, Wright A J, Thompson R L, Wilson W R, Washington J A., II Microbiological and clinical evaluation of the ISOLATOR lysis-centrifugation blood culture tube. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;17:864–869. doi: 10.1128/jcm.17.5.864-869.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iralu J V, Sritharan V K, Pieciak W S, Wirth D F, Maguire J H, Barker R H. Diagnosis of Mycobacterium avium bacteremia by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1811–1814. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.7.1811-1814.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kristiansen B E, Ask E, Jenkins A, Fermer C, Radstrom P, Skold O. Rapid diagnosis of meningococcal meningitis by polymerase chain reaction. Lancet. 1991;337:1578–1569. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lane D J, Pace B, Olsen G J, Stahl D A, Sogin M L, Pace N R. Rapid determination of 16S ribosomal RNA sequences for phylogenetic analyses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6955–6959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.20.6955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.La Scolea L, Jr, Dryja D. Quantitation of bacteria in cerebrospinal fluid and blood of children with meningitis and its diagnostic significance. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:187–190. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.2.187-190.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leibovici L, Konisberger H, Pitlik S D, Samra Z, Drucker M. Bacteremia and fungemia of unknown origin in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:436–443. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.2.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radstrom P, Backman A, Qian N, Kragssbjerg P, Pahlson C, Olcen P. Detection of bacterial DNA in cerebrospinal fluid by an assay for simultaneous detection of Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae, and streptococci using a seminested PCR strategy. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2738–2744. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2738-2744.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ratnamohan V M, Cunningham A L, Rawlinson W D. Removal of inhibitors of CSF-PCR to improve diagnosis of herpesviral encephalitis. J Virol Methods. 1998;72:59–65. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudolph K M, Parkinson A J, Black C M, Mayer L W. Evaluation of polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2661–2666. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2661-2666.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Washington J A, II, Ilstrup D M. Blood cultures: issues and controversies. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8:792–802. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.5.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinstein M P, Murphy J R, Reller L B, Lichtenstein K A. The clinical significance of positive blood cultures: a comprehensive analysis of 500 episodes of bacteremia and fungemia in adults. II. Clinical observations, with emphasis on factors influencing prognosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5:54–70. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson K H, Blitchington R B, Greene R C. Amplification of bacterial 16S ribosomal DNA with polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1942–1946. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1942-1946.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Isaacman D J, Wadowsky R M, Rydquist-White J, Post J C, Ehrlich G D. Detection of Streptococcus pneumoniae in whole blood by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:596–601. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.596-601.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]