Abstract

Background

Depression occurs frequently in individuals with coronary artery disease (CAD) and is associated with a poor prognosis.

Objectives

To determine the effects of psychological and pharmacological interventions for depression in CAD patients with comorbid depression.

Search methods

We searched the CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL databases up to August 2020. We also searched three clinical trials registers in September 2021. We examined reference lists of included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and contacted primary authors. We applied no language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs investigating psychological and pharmacological interventions for depression in adults with CAD and comorbid depression. Our primary outcomes included depression, mortality, and cardiac events. Secondary outcomes were healthcare costs and utilisation, health‐related quality of life, cardiovascular vital signs, biomarkers of platelet activation, electrocardiogram wave parameters, non‐cardiac adverse events, and pharmacological side effects.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently examined the identified papers for inclusion and extracted data from the included studies. We performed random‐effects model meta‐analyses to compute overall estimates of treatment outcomes.

Main results

Thirty‐seven trials fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Psychological interventions may result in a reduction in end‐of‐treatment depression symptoms compared to controls (standardised mean difference (SMD) −0.55, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.92 to −0.19, I2 = 88%; low certainty evidence; 10 trials; n = 1226). No effect was evident on medium‐term depression symptoms one to six months after the end of treatment (SMD −0.20, 95% CI −0.42 to 0.01, I2 = 69%; 7 trials; n = 2654). The evidence for long‐term depression symptoms and depression response was sparse for this comparison. There is low certainty evidence that psychological interventions may result in little to no difference in end‐of‐treatment depression remission (odds ratio (OR) 2.02, 95% CI 0.78 to 5.19, I2 = 87%; low certainty evidence; 3 trials; n = 862). Based on one to two trials per outcome, no beneficial effects on mortality and cardiac events of psychological interventions versus control were consistently found. The evidence was very uncertain for end‐of‐treatment effects on all‐cause mortality, and data were not reported for end‐of‐treatment cardiovascular mortality and occurrence of myocardial infarction for this comparison.

In the trials examining a head‐to‐head comparison of varying psychological interventions or clinical management, the evidence regarding the effect on end‐of‐treatment depression symptoms is very uncertain for: cognitive behavioural therapy compared to supportive stress management; behaviour therapy compared to person‐centred therapy; cognitive behavioural therapy and well‐being therapy compared to clinical management. There is low certainty evidence from one trial that cognitive behavioural therapy may result in little to no difference in end‐of‐treatment depression remission compared to supportive stress management (OR 1.81, 95% CI 0.73 to 4.50; low certainty evidence; n = 83). Based on one to two trials per outcome, no beneficial effects on depression remission, depression response, mortality rates, and cardiac events were consistently found in head‐to‐head comparisons between psychological interventions or clinical management.

The review suggests that pharmacological intervention may have a large effect on end‐of‐treatment depression symptoms (SMD −0.83, 95% CI −1.33 to −0.32, I2 = 90%; low certainty evidence; 8 trials; n = 750). Pharmacological interventions probably result in a moderate to large increase in depression remission (OR 2.06, 95% CI 1.47 to 2.89, I2 = 0%; moderate certainty evidence; 4 trials; n = 646). We found an effect favouring pharmacological intervention versus placebo on depression response at the end of treatment, though strength of evidence was not rated (OR 2.73, 95% CI 1.65 to 4.54, I2 = 62%; 5 trials; n = 891). Based on one to four trials per outcome, no beneficial effects regarding mortality and cardiac events were consistently found for pharmacological versus placebo trials, and the evidence was very uncertain for end‐of‐treatment effects on all‐cause mortality and myocardial infarction.

In the trials examining a head‐to‐head comparison of varying pharmacological agents, the evidence was very uncertain for end‐of‐treatment effects on depression symptoms. The evidence regarding the effects of different pharmacological agents on depression symptoms at end of treatment is very uncertain for: simvastatin versus atorvastatin; paroxetine versus fluoxetine; and escitalopram versus Bu Xin Qi.

No trials were eligible for the comparison of a psychological intervention with a pharmacological intervention.

Authors' conclusions

In individuals with CAD and depression, there is low certainty evidence that psychological intervention may result in a reduction in depression symptoms at the end of treatment. There was also low certainty evidence that pharmacological interventions may result in a large reduction of depression symptoms at the end of treatment. Moderate certainty evidence suggests that pharmacological intervention probably results in a moderate to large increase in depression remission at the end of treatment. Evidence on maintenance effects and the durability of these short‐term findings is still missing. The evidence for our primary and secondary outcomes, apart from depression symptoms at end of treatment, is still sparse due to the low number of trials per outcome and the heterogeneity of examined populations and interventions. As psychological and pharmacological interventions can seemingly have a large to only a small or no effect on depression, there is a need for research focusing on extracting those approaches able to substantially improve depression in individuals with CAD and depression.

Plain language summary

Treatments for depression in individuals with coronary artery disease

This review examined clinical trials on psychological treatments and antidepressant drugs in individuals with coronary artery disease and depression. The objective was to determine the effects of these treatments on depression, mortality, cardiac events such as another heart attack, or heart surgery.

We identified 37 trials as relevant for the review. Fifteen trials investigated psychological treatments, and 21 trials investigated pharmacological interventions including antidepressant drugs.

Generally, psychological treatments compared to controls, and antidepressant drugs compared to placebo (inactive drug), may result in a reduction in depression symptoms at the end of treatment; however, the evidence is generally of low certainty. The evidence is very uncertain as to whether psychological treatments compared to control and antidepressant drugs compared to placebo reduce mortality and cardiovascular events.

The evidence is current to August 2020.

Summary of findings

Background

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is amongst the leading causes of death for both men and women in middle‐ and high‐ income countries (Roth 2017). A strong association between CAD and comorbid depression has been consistently reported (Baune 2012; Kendler 2009; Scherrer 2003; Schulman‐Marcus 2016; Stenman 2014), which is similar to the association observed in other chronic disease populations (Chen 2019; Härter 2007; Matte 2016; Mezuk 2015; Petrak 2015). Results from the World Mental Health Surveys, Ormel 2007, indicate a twofold increased risk of depression for individuals with heart disease compared to those without heart disease and conversely, an increased risk of developing incident heart disease in individuals with depression compared to those without depression (Scott 2013). Prevalence rates of major depression in CAD populations, including those undergoing coronary revascularisation procedures, range from 15% to 20% (Nieuwsma 2017; Thombs 2008; Tully 2012), and are thus disproportionate to that observed in the general community (Kessler 2010).

The increased prevalence rates raise the issue of the impact of comorbid depression on the lives of these individuals and the healthcare system. Several original studies and systematic reviews document a significant prognostic association between comorbid depression and increased mortality, morbidity, and healthcare costs, as well as diminished quality of life and adherence to treatment regimen (Abberger 2017; Barth 2004; Baumeister 2011c; Frasure‐Smith 2003a; Frasure‐Smith 2008; Lichtman 2014; Nicholson 2006).

Description of the condition

Coronary artery disease is one of the most common forms of heart disease. One of the main underlying problems in cardiovascular disease is atherosclerosis, a process that obstructs blood vessels with deposits of fat, cholesterol, and other substances (WHO 1992). It is most serious when it restricts the blood supply to the heart itself (myocardial ischaemia). Clinical manifestations of CAD are acute coronary syndrome comprising myocardial infarction (MI) and unstable angina (Antman 2004), as well as stable angina pectoris (Fox 2006). MI refers to what is commonly known as a 'heart attack'. It occurs when prolonged myocardial ischaemia leads to myocardial cell death (necrosis) (Alpert 2000).

Depression is an emotional state characterised by strong feelings of sadness, worthlessness and guilt, withdrawal from others, sleeplessness, and loss of appetite, sexual desire, and interest in usual activities (Davison 2003), occurring in several subtypes (Baune 2012). Two key diagnostic criteria for major depression are depressed mood and loss of pleasure or interest in activities (anhedonia; APA 2013). Depressive disorders can be reliably diagnosed through structured clinical interviews. The severity of depressive symptoms is usually assessed by patient‐ or clinician‐administered rating scales that have undergone psychometric validation. Cut‐off scores have been validated for these scales that correspond to the likelihood of an indication of depression (Sadock 2009). Recommendations for the assessment of depression in individuals with cardiovascular disease are available (Davidson 2006; Lichtman 2014; Nieuwsma 2017; Thombs 2008).

Description of the intervention

Psychological interventions comprise cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), psychodynamic psychotherapy, interpersonal therapy (IPT), other approaches such as problem‐solving therapy, non‐directive or supportive therapy and counselling as well as single techniques of these interventions (Davison 2003). Other interventions comprise acceptance and commitment therapy, mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy and mindfulness‐based stress reduction, emotion‐focused therapy, and metacognitive therapy (Australian Psychological Society 2018). The mode of delivery comprises individual, group, or family (including couple) therapy carried out by a healthcare professional.

A network meta‐analysis comparing seven psychotherapeutic approaches concluded that most approaches were equally effective, with IPT being more effective than supportive therapy (Cohen's d = −0.30, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.54 to −0.05) (Barth 2013). However, this conclusion needs to be considered preliminary, as single trials lack statistical power, and meta‐analyses are limited by the heterogeneous methodological standards of primary studies (Cuijpers 2016). This might be even more true regarding psychological depression interventions for individuals with CAD, given the diversity of psychological interventions offered, from nurse‐led and low‐intensive, two‐session interventions to regular psychotherapies with at least 12 to 16 therapy sessions, offered at varying time points post‐cardiac event (Baumeister 2011c; Baumeister 2012b; Doyle 2021).

Antidepressant drugs are commonly used treatments in people with depression. In general, the available medications do not differ in their overall efficacy and effectiveness, but differ substantially with regard to short‐ and long‐term side effects (NICE 2009; Sadock 2009). Antidepressant treatment selection depends on the type of depressive disorder and the presence of comorbid somatic or mental disorders. The main pharmacological classes of antidepressant medications are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). For CAD patients with moderate, severe, or recurrent depression, SSRIs are viewed as safe and effective pharmacological agents (Lichtman 2008). In contrast, TCAs and MAOIs are contraindicated in CAD patients because of their cardiac side effects such as prolongation of the QT interval on electrocardiogram (Lichtman 2008). Other potential pharmacological interventions include repurposing vascular drugs intended to lower cholesterol or blood pressure for the treatment of depression (Cipriani 2016; Taragano 2005). In addition, interventions may explore diet and supplements such as n‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, also known as omega‐3 oils (Appleton 2015).

A systematic review experimentally comparing psychological or psychotherapy and pharmacological approaches indicated that overall, psychological and pharmacological interventions are equally effective for treating depression, with pharmacotherapy seemingly being superior in dysthymia (Hedges' g = 0.3) as well as compared to non‐directive counselling (Hedges' g = 0.33), and psychotherapy being superior to tricyclic antidepressants (Hedges' g = 0.21) (Cuijpers 2013). Combining both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is superior to pharmacotherapy alone at six months or longer postrandomisation (odds ratio (OR) 2.93). However, and conversely, psychotherapy alone compared to combined therapy resulted in equal depression effects at six months follow‐up and longer (Karyotaki 2016).

How the intervention might work

Many biological and behavioural mechanisms linking CAD and depression have been proposed (Carney 2017; Härter 2007a; Joynt 2003; Musselman 1998; Skala 2006), comprising pathophysiological pathways such as decreased heart rate variability, platelet activation, and endothelial dysfunction in depressed CAD patients (Antman 2004). Furthermore, an accumulation of behavioural (smoking, physical inactivity, and imbalanced diet) and medical risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, and obesity) in depressed patients might affect the development and course of CAD (Joynt 2003; Whooley 2008). Psychosocial stress constitutes a risk factor for both CAD and depression (Joynt 2003).

A review concluded that pharmacological interventions for depression might influence physiological pathways linking depression and CAD (Carney 2017). Psychological treatments may also affect physiological processes, but the interrelations between behavioural and physiological mechanisms remain less clear (Carney 2017). Psychological interventions might improve not only depression outcomes in CAD patients with comorbid depressive disorder, but also medical outcome parameters, by encouraging behaviour changes towards a healthier lifestyle in these patients (Firth 2019; Richards 2017).

Why it is important to do this review

Due to high prevalence rates and the impact of comorbid depression on both medical and psychosocial outcomes, there is a need for effective depression treatments in CAD. In various systematic reviews, psychological and psychopharmacological interventions have proven to be effective interventions for the treatment of major depression (Cuijpers 2008a; Cuijpers 2008b; Cuijpers 2013; Karyotaki 2016; NICE 2009; Sadock 2009). However, the evidence on the effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological depression interventions for people with CAD and depression is far less conclusive (Baumeister 2011c), and prone to bias in the literature (Doyle 2021), which argues for an update of our Cochrane Review. Several clinical guidelines recommend depression intervention in CAD populations whilst noting the limited efficacy in preventing major adverse cardiac events, based on few trials to date (Hillis 2011; Lichtman 2014).

Another Cochrane Review examined the effects of non‐specific psychological interventions in CAD patients and found small to moderate reductions in depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms as well as a 22% reduction in MI compared to usual care (Richards 2017). However, the review did not study the effects of depression‐specific treatment in the population of CAD patients with a comorbid depressive disorder or depression symptoms. Furthermore, the review included non‐specific psychological interventions and interventions delivered in combination with cardiac rehabilitation, whereas the focus of our review is on depression‐specific psychological or pharmacological interventions explicitly used for treating depression in populations with depression. Some randomised controlled trials may be included in both reviews, but the research questions remain different owing to the focus of our review on the effects of depression treatments in depressed CAD patients.

The current review will permit the drawing of conclusions on the effects of depression treatment in CAD patients with comorbid depressive disorders. Depending on the number of primary studies, conclusions may be drawn concerning differential effects of type of intervention on depression and mortality or cardiovascular events, as well as on participant quality of life (QoL), thus providing a basis for treatment recommendations. Furthermore, follow‐up data may be examined concerning the healthcare costs of the interventions. Sources of heterogeneity in the results of the primary studies can be explored and could help provide suggestions for the design of future studies.

Objectives

To determine the effects of psychological and pharmacological interventions for depression in CAD patients with comorbid depression.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled clinical trials (RCTs) of any length of treatment and any length of follow‐up. Both individually and cluster‐randomised clinical trials were eligible. We included studies reported as full text, those published as abstract only, and unpublished data.

Types of participants

Adults (18 years or older) with CAD (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD‐10): I20‐I25, WHO 1992, or later versions of the ICD) and comorbid depressive disorder (ICD‐10: F32/33/34.1 (WHO 1992); Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised (DSM‐III‐R): 296.xx; 300.4, APA 1987, or later versions of diagnostic classification systems; including subthreshold conditions) assessed by standardised interviews, self‐reports, medical records, or physicians' diagnosis. Studies comprised of individuals with non‐CAD conditions were ineligible. Inclusion of primary studies was not further limited to specific clinical subgroups in order to increase the generalisability of the results of the review.

With regard to comorbid depression, studies comprising mixed study samples (e.g. both depressed CAD patients and CAD patients with low social support (ENRICHD 2003)) were included in the review.

Types of interventions

Psychological interventions comprise CBT, psychodynamic psychotherapy, IPT, non‐directive or supportive therapy and counselling (Davison 2003), acceptance and commitment therapy, mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy, mindfulness‐based stress reduction, emotion‐focused therapy, and metacognitive therapy (Australian Psychological Society 2018). In the first instance, we pooled all psychological interventions together, conducted analyses of heterogeneity, and took this into consideration when adjudicating the strength of evidence. The mode of delivery was defined as individual, group, or family (including couple) therapy carried out in whole or in part by a healthcare professional. The comparison group was defined consistent with a similar review of type 1 diabetes interventions (Winkley 2020): 'no intervention', 'usual care', 'wait‐list control', 'attention‐control' or 'clinical management' (CM).

With regard to differential or incremental effects of different treatment approaches, we also considered trials with a control group receiving pharmacological treatment or another psychological treatment (Comparison 2 and Comparison 4). In accordance with the previous review (Baumeister 2011c), we grouped separately studies using CM as a comparator intervention or other psychological intervention. The rationale for this was that CM, which consists of information about depression and depression treatment, provides a more concerted approach to depression management than does usual care (CREATE 2007), with CM delivered by health professionals and often for equal intensity as an intervention. By contrast, usual care commonly involves no depression treatment at all, even when incentives are provided (Jani 2013; Rollman 2009). In head‐to‐head comparison trials of psychological interventions or CM, we abstained from pooling across different treatments, consistent with the original review (Baumeister 2011c), owing to the heterogeneity in clinical interventions and their heterogenous comparators.

Pharmacological interventions included all antidepressant medications and other drug therapies used explicitly for treating depressive disorders (Sadock 2009). The control group was placebo. In the first instance, we pooled all pharmacological interventions and conducted analyses of heterogeneity. We included pharmacological treatments compared to other pharmacological medications, as well as add‐on therapies or augmentation strategies, or by comparison to psychological interventions, to determine differential or incremental effects. In accordance with the previous review (Baumeister 2011c), we grouped separately head‐to‐head comparison trials of pharmacological interventions. We abstained from pooling across different studies owing to the heterogeneity in clinical interventions and their heterogenous comparators.

Types of outcome measures

Reporting one or more of the outcomes listed here in the trial was not an inclusion criterion for the review. Where a published report did not appear to report one of these outcomes, we accessed the trial protocol and contacted the trial authors to ascertain whether the outcomes were measured but not reported. Relevant trials that measured these outcomes but did not report the data at all, or not in a useable format, were included in the review as part of the narrative.

We assessed outcomes at three follow‐up periods, consistent with the previous review by Baumeister 2011c:

short term (at the end of treatment), which was the primary time point of clinical interest for the review;

medium term (one to six months after the end of treatment);

long term (more than six months after the end of treatment).

Multiple observations in primary studies were allocated to separate analyses by different time frames, which reflect short‐, medium‐, and long‐term follow‐up. The rationale for subdividing outcomes by time was to assess the durability of interventions, given that evidence was sparse for longer‐term outcomes in the previous review (Baumeister 2011c).

Primary outcomes

Depression (measured either dimensionally or categorically) following the intervention, as assessed by validated self‐report questionnaires or standardised interviews. Depression may be quantified categorically as 'remitted' or 'response', the latter defined as a 50% or more reduction in severity from baseline.

All‐cause mortality.

Cardiovascular mortality.

-

Non‐fatal cardiac events according to standardised criteria (e.g. WHO 1992 or subsequent iterations):

myocardial infarction (MI);

angina;

heart failure;

arrhythmia;

stroke;

Coronary revascularisation for CAD: coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) and/or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or angioplasty.

We analysed the primary outcomes separately and abstained from pooling a composite outcome, with two exceptions: 1) acute coronary syndromes (inclusive of ST and non‐ST elevated MI, and/or unstable angina) were collapsed into MI (for one study, U‐CARE 2018); and 2) coronary revascularisation for CAD was inclusive of CABG and/or PCI or angioplasty. Here we grouped coronary revascularisation for CAD under cardiac events, as opposed to healthcare utilisation, in line with common definitions of major adverse cardiac events (Bosco 2021).

Secondary outcomes

-

Healthcare costs or resource utilisation, including:

hospitalisations;

emergency department visits;

length of stay.

Health‐related quality of life.

-

Cardiovascular vital signs:

systolic blood pressure (BP) measured in mmHg;

diastolic BP measured in mmHg;

heart rate measured in beats per minute (bpm).

-

Biomarkers of platelet activation:

β‐thromboglobulin (βTG);

platelet factor 4 (PF4);

P‐selectin;

platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule‐1 (PECAM‐1);

thromboxane B2 (TxB2).

-

Electrocardiogram (ECG) wave recording in milliseconds:

PR interval;

QRS interval;

QT interval;

QTc interval.

Non‐cardiac adverse events (psychiatric admission, suicide, worsening depression). In pharmacological interventions side effects were also assessed.

Analysis of the secondary outcomes cardiovascular vital signs and biomarkers of platelet activation was considered in the previous review but not reported (Baumeister 2011c). We also added important adverse effects (ECG wave recording, non‐cardiac adverse events, and pharmacological side effects) to this updated review, which we define as post hoc outcomes. We analysed the secondary outcomes separately and abstained from pooling any composite outcomes apart from pharmacological side effects, which we considered as a composite of any quantified side effect by self‐report scale, checklist, or adverse outcome.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases for RCTs of treatment of depressive disorders in CAD patients on 3 August 2020:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Cochrane Library, Issue 8 of 12, 2020);

Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, MEDLINE Daily and MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to 31 July 2020);

Embase (Ovid, 1980 to 2020 Week 31);

PsycINFO (Ovid, 1806 to July Week 4 2020);

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (EBSCO, 1937 to 3 August 2020);

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and NHS Economic Evaluation Database (EED) (Cochrane Library, Issue 2 of 4, 2015);

Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA) (Cochrane Library Issue 4 of 4, 2016).

The Cochrane sensitivity‐maximising RCT filter was used for MEDLINE, and for Embase, terms as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions were applied (Lefebvre 2011). Adaptations of these RCT filters were applied to the other databases, except CENTRAL. See Appendix 1 for details of the 2009 search strategies and Appendix 2 for the updated 2020 search strategies. No language restrictions were applied.

Searching other resources

We searched the World Heath Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (https://trialsearch.who.int/), ISRCTN registry (http://isrctn.org/), and ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov) on 2 September 2021 (Appendix 2). We also examined the reference lists of all included trials to identify other potentially relevant studies. We contacted corresponding authors of the included trials to ask about other RCTs, published or unpublished, which might be relevant to the review. We handsearched the list of included and excluded studies in the Cochrane Review by Richards 2017 and the network meta‐analysis by Doyle 2021.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

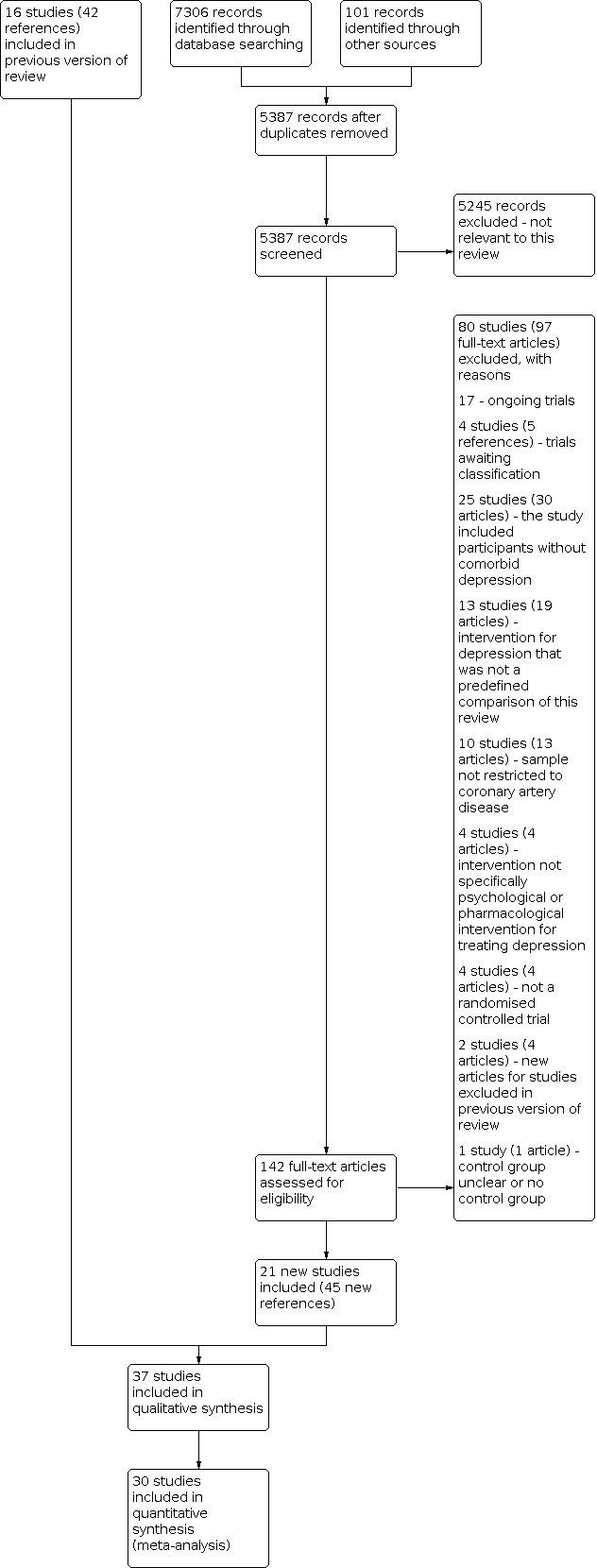

Two review authors independently in pairs selected studies for inclusion (original review: NH, HB; update: SYA, EJLL, EB, NB). We examined a list of titles and abstracts; if title and abstract contained sufficient information to determine exclusion, the article was rejected. We retrieved the full papers of all remaining articles, which two review authors independently reviewed. In addition, any other potentially relevant articles identified by checking the reference lists or personal communications were also reviewed. We kept a record of all rejected papers and the reasons for rejection. We used this information to construct a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1), and reported the reasons for exclusion of excluded studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Important parts of foreign language papers of included studies (i.e. not English, German, or Chinese) were translated into English. If the two review authors disagreed about the inclusion of an article, a third review author (original review: JB; update: PJT) was asked to review the article. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus discussion.

1.

Summary of the 2020 literature search update and study selection.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (original review: HB, NH; update: PJT, SYA, EJLL, NB, EB) independently in pairs extracted data from the full copies of primary studies using a data extraction form. We extracted study characteristics including participants (sample size at baseline and follow‐up, type of CAD, gender, age), type of depression (major depression, minor depression or dysthymic disorder), assessment method (standardised diagnostic interview, self‐report questionnaire, medical record or physician’s diagnosis), cut‐off used to indicate depression on self‐report questionnaire, type of intervention (type of psychological treatment versus type of pharmacological treatment), comparison group (usual care, other control, another psychological treatment or pharmacological treatment), length of follow‐up, descriptive statistics of primary and secondary outcomes, effect sizes and confidence intervals.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (original review HB, NH; update: PJT, SYA, EJLL, EB, NB) independently in pairs assessed risk of bias in the included studies using Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). We described sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. With regard to psychological interventions, blinding of healthcare providers or participants to the treatment is not feasible. In pharmacological trials blinding is possible for participants, personnel, and outcome assessors, and was evaluated accordingly. We considered a trial as having an overall high risk of bias when four domains out of six were assessed as high or unclear for: allocation (sequence generation and concealment), blinding (participants, personnel, and outcome assessors), incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. In the event that we identified an other source of bias at high risk, this also contributed to the overall adjudication of a trial at high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Continuous outcomes measured using different scales necessitated the standardisation of the results of the studies to a uniform scale. We computed standardised mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous outcomes measured using different scales. As a first preference we analysed the mean scores of final assessment, followed by mean change scores from baseline to final assessment if only these scores were available. If no measures of variability were provided in the study reports, we used exact P values as well as t‐statistic or Chi2 statistic to compute an SMD.

For dichotomous variables, we computed odds ratios (OR) with 95% CI. For continuous primary and secondary outcomes assessed by the same method (i.e. Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM‐D), BP, heart rate, ECG parameters), we used a mean difference (non‐standardised).

Several strategies have been proposed to help readers interpret results presented as SMDs (e.g. re‐expressing SMDs using Cohen's rules of thumb for effect sizes (Cohen 1988), re‐expressing SMDs by transformation to OR, re‐expressing SMDs using a familiar instrument, reporting the ratio of the means, or expressing as minimal important difference units; see also Section 15.5.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions) (Higgins 2011). However, all of these strategies have substantial disadvantages and introduce imprecision. For example, re‐expressing SMDs by means of familiar instruments does not account for between‐study heterogeneity. An SMD of a specific magnitude translates into different scores (e.g. on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)) depending on, for example, the baseline severity of depression. Conclusions based on this strategy might thus be substantially misleading. We decided to use the rule of thumb proposed by Cohen 1988 and suggested by the Cochrane Handbook to re‐express SMDs (Higgins 2011). Based on the assumptions of Cohen 1988, SMDs around 0.2 must be regarded as small, 0.5 as moderate, and 0.8 as large. As previously mentioned, this strategy also comprises substantial disadvantages, as a small, moderate, or large effect size depends on the specific outcome and the assessment instrument being used. Moreover, patient importance of a finding is context‐dependent and not amenable to generic statements (Higgins 2011). When interpreting the results (Baumeister 2012b), readers should keep this limitation of the rules of thumb in mind (Cohen 1988).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis in the primary studies was the participant, which is randomised to either the treatment or control group. The number of observations thus matches the number of units that are randomised. In instances where observational units were correlated (e.g. by cluster), we planned to reduce the sample to an 'effective sample size', dividing the original sample size by the ‘design effect’ (Higgins 2021).

Dealing with missing data

We requested missing information from published RCTs from the corresponding authors or obtained it from trial data repositories. Of 18 authors contacted for missing data, five replied, and three were able to provide at least some of the requested data. No imputation methods were used due to the small amount of trials per outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested for statistically significant heterogeneity using the Q‐statistics with a 95% CI. We computed the I2 to examine the extent of heterogeneity. Meta‐analytically pooled effect estimates should be interpreted in accordance with any substantial clinical or methodological or statistical heterogeneity. We planned to specifically examine heterogeneity with the I2 statistic quantifying inconsistency across studies to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis. Interpretation of heterogeneity would include the magnitude and direction of effects, the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from the Chi2 test), and the I2 statistic where:

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2021).

A meta‐regression was considered to explore potential sources of heterogeneity but was not performed owing to the small amount of trials per outcome.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not create funnel plots to investigate reporting bias due to the limited number of trials per outcome (Higgins 2021). To examine outcome reporting bias, we analysed discrepancies in reported outcomes between published protocols and original papers. Where no protocol was available, we contacted the corresponding trial authors for published or unpublished protocols.

Data synthesis

We performed random‐effects meta‐analyses to compute overall estimates of treatment outcomes based on the assumption of high clinical and methodological heterogeneity between RCTs. Both SMD and OR effect sizes were pooled using the inverse‐variance method, which is best suited to random‐effects meta‐analysis (Higgins 2011). The effect sizes of the primary studies are presented in forest plots. In the case of considerable methodological heterogeneity owing to different intervention types and their heterogenous comparators, we abstained from meta‐analytical pooling of trial results (Comparison 2: psychological versus psychological/CM; Comparison 4: pharmacological versus pharmacological). Where no dichotomous events occurred in both arms of a trial, we described the finding narratively in the text and in the summary of findings tables.

In the case of multiple assessment tools used for the same outcome, we followed a hierarchical approach to decide which assessment to use in the meta‐analyses. Clinician‐rated assessments were given priority over patient self‐report questionnaires. In the case of assessment tools on the same hierarchical level, we chose the most frequently used assessment tool across the included studies, followed by the measure with the least missing data (per‐protocol), followed by random selection of one of the assessment tools.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned subgroup analyses to examine the impact of sex (men versus women), CAD subtype, time of onset of depression (pre‐existing versus new‐onset depression), CAD severity, and risk of bias of included studies on the results, but did not conduct them due to the sparseness of trial data. We will reconsider these subgroup analyses in future updates of the review.

Sensitivity analysis

Because pooling results across different types of psychological interventions may level out specific treatment effects and be potentially misleading (Baumeister 2011c), we conducted sensitivity analysis on depression symptoms at end of treatment to update the results of Baumeister 2011c for Comparison 1: psychological versus control and Comparison 3: pharmacological versus placebo. For Comparison 1, we performed sensitivity analysis in CBT‐only trials, and similarly in Comparison 3 conducted sensitivity analysis restricted to serotonergic antidepressant interventions. Specifically, the sensitivity analysis included SSRIs and mirtazepine, which can be classed as a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant and tetracyclic analogue (see Types of interventions) (de Boer 1995). We also performed sensitivity analyses according to depressive disorders and secondly by depression‐only trials (e.g. excluding mixed depression/anxiety studies).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We assessed the certainty of the evidence for the primary outcomes (short‐term) using the GRADE approach (GRADEpro GDT), which takes into consideration risk of bias (see Assessment of risk of bias in included studies), consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias (Schünemann 2019). We constructed a summary of findings table for the primary outcomes (short‐term, end of treatment) for five outcomes: depression symptoms, depression remission, all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and occurrence of MI. We made comments narratively to qualitatively describe the certainty of the evidence for the five end‐of‐treatment outcomes per comparison.

Results

Description of studies

See: PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1), Characteristics of included studies; Table 5; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

1. Overview of study population.

| Study ID | Intervention | [n]screened | [n] randomised | [n] ITT | [n] finishing study | [%] of randomised participants finishing study | Comments |

| Abbasi 2015 | Intervention 1 (I1): simvastatin Intervention 2 (I2): atorvastatin |

Total: 206 | I1: 29 I2: 29 Total: 58 |

I1: NR I2: NR Total: NR (per‐protocol) |

I1: 23 I2: 23 Total: 46 |

I1: 79.3% I2: 79.3% Total: 79.3% |

|

| ANDROS 2015 | Intervention (I): sertraline Control (C): placebo |

Total: ? | I: ? C: ? Total: 2 |

I: ? C: ? Total: ? |

I: ? C: ? Total: ? |

I: ? C: ? Total: ? |

Comment: trial terminated early, no results posted |

| Barth 2005 | Intervention (I): resource‐orientated psychotherapy Control (C): usual care |

Total: 1709 | I: 27 C: 32 Total: 59 |

I: 27 C: 32 Total: 59 (per‐protocol) |

I: 27 C: 28 Total: 55 |

I: 100% C: 87.5% Total: 93.2% |

|

| Brown 1993 | Intervention 1 (I1): behaviour therapy Intervention 2 (I2): person‐centred therapy |

Total: 107 | I1: NR I2: NR Total: 54 |

I1: NR I2: NR Total: NR (per‐protocol) |

I1: 20 I2: 20 Total: 40 |

I1: ? I2: ? Total: 74.1% |

Comment: dropout reported in text, no flow chart |

| CREATE 2007 | Intervention 1 (I1): interpersonal psychotherapy, citalopram, clinical management Intervention 2 (I2): citalopram, clinical management Control 1 (C1): interpersonal psychotherapy, placebo, clinical management Control 2 (C2): placebo, clinical management |

Total: 1897 | I1: 67 I2: 75 C1: 75 C2: 67 Total: 284 |

I1: 67 I2: 75 C1: 75 C2: 67 Total: 284 |

I1: 59 I2: 72 C1: 59 C2: 47 Total: 237 |

I1: 88.1% I2: 96.0% C1: 78.7% C2: 70.1% Total: 83.5% |

Comment: 2 x 2 factorial trial; only I2 and C2 data are eligible for this review |

| Carney 2009 | Intervention 1 (I1): sertraline plus omega‐3 Intervention 2 (I2): sertraline plus placebo |

Total: 941 | I1: 62 I2: 60 Total: 122 |

I1: 62 I2: 60 Total: 122 |

I1: 59 I2: 56 Total: 115 |

I1: 95.2% I2: 93.3% Total: 94.3% |

|

| Dao 2011 | Intervention (I): cognitive‐ behavioural therapy C: usual care |

Total: 513 | I: 50 C: 50 Total: 100 |

I: NR C: NR Total: NR (per‐protocol) |

I: 48 C: 48: Total: 96 |

I: 96% C: 96% Total: 96% |

|

| Divsalar 2018 | Intervention 1 (I1): sertraline plus red yeast rice Intervention 2 (I2): sertraline plus placebo |

Total: 101 | I1: 28 I2: 28 Total: 56 |

I1: NR I2: NR Total: NR |

I1: 25 I2: 25 Total: 50 |

I1: 89.3% I2: 89.3% Total: 89.3% |

|

| Doering 2007 | Intervention (I): cognitive‐ behavioural therapy Control (C): usual care |

Total: 117 | I: NR C: NR Total: NR |

I: NR C: NR Total: NR (per‐protocol) |

I: 7 C: 8 Total: 15 |

I: ? C: ? Total: ? |

Comment: reasons for dropout not stated, no flow chart Comment: nested trial within observational study (non‐depressed cohort) |

| EsDEPACS 2014 | Intervention (I): escitalopram Control (C): placebo |

Total: 4809 | I:149 C: 151 Total: 300 |

I: 108 C: 109 Total: 217 (per‐protocol) |

I: 78 C: 79 Total: 157 |

I: 52.3% C: 52.3% Total: 52.3% |

Comment: nested trial within observational study (depressed cohort receiving usual care) |

| ENRICHD 2003 | Intervention (I): cognitive‐ behavioural therapy Control (C): usual care |

Total: 33780 | I: 1238 C: 1243 Total: 2481 |

I: 1238 C: 1243 Total: 2481 |

I: 983 C: 985 Total: 1968 |

I: 79.4% C: 79.2% Total: 79.3% |

|

| Fang 2003 | Intervention (I): health education and psychological intervention Control (C): usual care |

Total: ? | I: 27 C: 30 Total: 57 |

I: ? C: ? Total: ? |

I: ? C: ? Total: ? |

I: ? C: ? Total: ? |

Comment: translated paper |

| Freedland 2009 | Intervention 1 (I1): cognitive‐ behavioural therapy Intervention 2 (I2): supportive stress management Control (C): usual care |

Total: 2955 | I1: 41 I2: 42 C1: 40 Total: 123 |

I1: 41 I2: 42 C1: 40 Total: 123 |

I1: 40 I2: 33 C1: ? Total: ? |

I1: 98% I2: 79% C1: ? Total: ? |

|

| Freeman 1986 | Intervention (I): alprazolam Control (C): placebo |

Total: 459 | I: 54 C: 53 Total: 107 |

I: NR C: NR Total: NR (per‐protocol) |

I: 32 C: 28 Total: 60 |

I: 59.3% C: 52.8% Total: 56.1% |

Comment: no flow chart |

| Kennedy 2005 | Intervention (I): escitalopram Control (C): placebo |

Total: NR | I: 9 C: 10 Total: 19 |

I: NR C: NR Total: NR (per‐protocol) |

I: 2 C: 2 Total: 4 |

I: 22.2% C: 20.0% Total: 21.1% |

Comment: trial terminated early, redacted results posted |

| Li 2005 | Intervention (I): St John's wort extract Control (C): placebo |

Total: ? | I: ? C: ? Total: 87 |

I: ? C: ? Total: ? |

I: 43 C: 39 Total: 82 |

I: ? C: ? Total: 94.3% |

Comment: translated paper |

| Liu 1999 | Intervention (I): fluoxetine Control (C): placebo |

Total: ? | I: ? C: ? Total: ? |

I: ? C: ? Total: ? |

I: 31 C: 37 Total: ? |

I: ? C: ? Total: ? |

Comment: translated paper |

| Liu 2016 | Intervention 1 (I1): sertraline and Shugan Jieyu Intervention 2 (I2): sertraline and placebo |

Total: 3907 | I1: 76 I2: 73 Total: 149 |

I1: 76 I2: 73 Total: 149 |

I1: 48 I2: 46 Total: 94 |

I1: 63.2% I2: 63.0% Total: 63.1% |

Comment: no flow chart, reasons for dropout reported in text |

| MIND‐IT 2007 | Intervention (I): mirtazapine Control (C): placebo |

Total: 2177 | I: 47 C: 44 Total: 91 |

I: 47 C: 44 Total: 91 |

I: 22 C: 18 Total: 40 |

I: 46.8% C: 40.9% Total: 44.0% |

Comment: nested trial within observational study (depressed cohort receiving usual care) |

| Ma 2019 | Intervention (I): Xinkeshu Control (C): placebo |

Total: 312 | I: 30 C: 30 Total: 60 |

I: NR C: NR Total: NR |

I: 28 C: 27 Total: 55 |

I: 93.3% C: 90% Total: 91.7% |

|

| McFarlane 2001 | Intervention (I): sertraline Control (C): placebo |

Total: 238 | I: 18 C: 20 Total: 38 |

I: NR C: NR Total: NR (per‐protocol) |

I: 12 C: 15 Total: 27 |

I: 66.7% C: 75.0% Total: 71.1% |

Comment: no flow chart, reasons for dropout reported in text |

| McLaughlin 2005 | Intervention (I1): telephone counselling Control (C): usual care |

Total: 700 | I: 53 C: 47 Total: 100 |

I: NR C: NR Total: NR (per‐protocol) |

I: 45 C: 34 Total: 79 |

I: 84.9% C: 72.3% Total: 79% |

|

| MoodCare 2011 | Intervention (I): cognitive‐ behavioural therapy Control (C): usual care | Total: 3071 | I: 61 C: 60 Total: 121 |

I: NR C: NR Total: NR |

I: 53 C: 53 Total: 106 |

I: 86.9% C: 88.3% Total: 87.6% |

|

| Pizzi 2009 | Intervention (I): sertraline Control (C): placebo |

Total: 630 | I: 50 C: 50 Total: 100 |

I: NR C: NR Total: NR (per‐protocol) |

I: 47 C: 48 Total: 95 |

I: 94% C: 96% Total: 95% |

|

| Roose 1998 | Intervention 1 (I1): paroxetine Intervention 2 (I2): nortriptyline |

Total: NR | I1: 41 I2: 40 Total: 81 |

I1: 41 I2: 40 Total: 81 |

I1: 37 I2: 30 Total: 67 |

I1: 90.2% I2: 75.0% Total: 82.7% |

Comment: no flow chart, reasons for dropout reported in text |

| SADHART 2002 | Intervention (I): sertraline Control (C): placebo |

Total: 11546 | I: 186 C: 183 Total: 369 |

I: 186 C: 183 Total: 169 |

I: 133 C: 137 Total: 270 |

I: 71.5% C: 74.9% Total: 73.1% |

|

| SPIRR‐CAD 2011 | Intervention (I): stepwise psychotherapy intervention Control (C): usual care |

Total: 21780 | I: 285 C: 285 Total: 570 |

I: 284 C: 284 Total: 568 |

I: 110 C: 194 Total: 304 |

I: 38.6% C: 68.1% Total: 53.3% |

|

| Shahmansouri 2014 | Intervention 1 (I1): fluoxetine Intervention 2 (I2): Crocus sativus L. (saffron) |

Total: 75 | I1: 22 I2: 22 Total: 44 |

I1: NR I2: NR Total: NR (per‐protocol) |

I1: 20 I2: 20 Total: 40 |

I1: 90.9% I2: 90.9% Total: 90.9% |

|

| Strik 2000 | Intervention (I): fluoxetine Control (C): placebo |

Total: 556 | I: 27 C: 27 Total: 54 |

I: 27 C: 27 Total: 54 |

I: 22 C: 18 Total: 40 |

I: 81.5% C: 66.7% Total: 74.1% |

|

| Tian 2016 | Intervention 1 (I1): paroxetine Intervention 2 (I2): fluoxetine |

Total: ? | I1: 23 I2: 23 Total: 46 |

I1: 23 I2: 23 Total: 46 (per‐protocol) |

I1: 23 I2: 23 Total: 46 |

I1: 100% I2: 100% Total: 100% |

Comment: no flow chart was reported. It is unclear whether 16 participants who did not finish the study were from I1 or I2 groups, or non‐treatment or non‐depressed groups. |

| TREATED‐ACS 2020 | Intervention 1 (I1): cognitive‐behavioural therapy and well‐being therapy Intervention 2 (I2): clinical management |

Total: 740 | I1: 50 I2: 50 Total: 100 |

I1: 50 I2: 50 Total: 100 |

I1: 42 I2: 40 Total: 82 |

I1: 84% I2: 80% Total: 82% |

|

| U‐CARE 2018 | Intervention (I): internet cognitive‐behavioural therapy Control (C): usual care |

Total: 3928 | I: 117 C: 122 Total: 239 |

I: 117 C: 122 Total: 239 |

I: 96 C: 115 Total: 211 |

I: 82.1% C: 94.3% Total: 88.3% |

|

| UPBEAT 2012 | Intervention 1 (I1): sertraline Intervention 2 (I2): exercise Control (C): placebo |

Total: 1680 | I1: 40 I2: 37 C: 24 Total: 101 |

I1: NR I2: NR C: NR Total: NR |

I1: 36 I2: 36 C: 23 Total: 95 |

I1: 90% I2: 97.3% C: 95.8% Total: 94.1% |

Comment: only I1 sertraline and C placebo are eligible for this review |

| Wang 2020 | Intervention 1 (I1): escitalopram Intervention 2 (I2): Bu Xin Qi decoction |

Total: 300 | I1: 140 I2: 140 Total: 280 |

I1: NR I2: NR Total: NR (per‐protocol) |

I1: 113 I2: 115 Total: 228 |

I1: 80.7% I2: 82.1% Total: 81.4% |

Comment: reasons for dropout not stated in flow chart |

| WIDeCAD 2017 | Intervention (I): internet cognitive‐behavioural therapy Control (C): wait‐list control |

Total: 72 | I: 18 C: 16 Total: 34 |

I: 18 C: 16 Total: 34 |

I: 13 C: 13 Total: 26 |

I: 72.2% C: 81.3% Total: 76.5% |

|

| Yang 2019 | Intervention (I): intensive telephone‐based care Control (C): usual care |

Total: 354 | I: 112 C: 112 Total: 224 |

I: NR C: NR Total: NR |

I: 107 C: 105 Total: 212 |

I: 95.5% C: 93.8% Total: 94.6% |

|

| Zarea 2014 | Intervention (I): Peplau's therapeutic communication model Control (C): usual care |

Total: ? | I: ? C: ? Total: ? |

I: ? C: ? Total: ? (per‐protocol) |

I: 37 C: 37 Total: 74 |

I: ? C: ? Total: ? |

Comment: total sample estimated from degrees of freedom in Table 3 |

ITT = intention‐to‐treat; NR = not reported; ? = unclear

Results of the search

The database and trial registry search resulted in 7407 references (101 from trial registries), 5387 of which were unique references. We excluded 5245 articles at the title/abstract level, and 80 studies (97 articles) after full‐text review, most commonly because the study did not investigate participants without comorbid depression (25 studies, 30 articles), the intervention for depression was not a predefined comparison of this review (13 studies, 19 articles), the sample was not restricted to CAD (10 studies, 13 articles), the intervention not specifically psychological or pharmacological intervention for treating depression (4 studies, 4 articles), the study was not an RCT (4 studies, 4 articles), the control group was unclear or there was no control group (1 study, 1 reference), or new citations to studies already excluded in the previous review (2 studies, 4 references). We also identified 17 ongoing studies (17 references) and 4 trials awaiting classification (5 references). Twenty‐one new studies were found to be eligible in this updated review (45 new references) and included in the narrative review or synthesis. See the study flow chart for details of the study selection process (Figure 1).

Included studies

Thirty‐seven trials fulfilled the inclusion criteria of the review (Abbasi 2015; ANDROS 2015; Barth 2005; Brown 1993; Carney 2009; CREATE 2007; Dao 2011; Divsalar 2018; Doering 2007; ENRICHD 2003; EsDEPACS 2014; Fang 2003; Freedland 2009; Freeman 1986; Kennedy 2005; Li 2005; Liu 1999; Liu 2016; Ma 2019; McFarlane 2001; McLaughlin 2005; MIND‐IT 2007; MoodCare 2011; Pizzi 2009; Roose 1998; SADHART 2002; Shahmansouri 2014; SPIRR‐CAD 2011; Strik 2000; Tian 2016; TREATED‐ACS 2020; U‐CARE 2018; UPBEAT 2012; Wang 2020; WIDeCAD 2017; Yang 2019; Zarea 2014).

Fifteen trials investigated psychological interventions, which comprised CBT (Dao 2011; Doering 2007; ENRICHD 2003; MoodCare 2011; U‐CARE 2018; WIDeCAD 2017), resource‐orientated psychotherapy (Barth 2005), telephone counselling (McLaughlin 2005; Yang 2019), individual and group psychotherapy (SPIRR‐CAD 2011), therapeutic communication sessions (Zarea 2014), and an intervention comprising health education and various psychological treatments (Fang 2003). One three‐arm trial examined CBT, supportive stress management, and usual care (Freedland 2009). One trial examined eight sessions of CBT in combination with four sessions of well‐being therapy versus CM (TREATED‐ACS 2020). One trial examined behaviour therapy versus person‐centred therapy (Brown 1993). Two psychological therapy trials delivered the CBT intervention entirely online with therapist or eCoach support (U‐CARE 2018; WIDeCAD 2017); all others delivered the intervention face‐to‐face.

Twenty‐one trials investigated the effects of pharmacological depression treatments with sertraline (ANDROS 2015; McFarlane 2001; Pizzi 2009; SADHART 2002; UPBEAT 2012), mirtazapine (MIND‐IT 2007), fluoxetine (Liu 1999; Strik 2000), escitalopram (EsDEPACS 2014; Kennedy 2005), paroxetine and nortriptyline (Roose 1998), paroxetine and fluoxetine (Tian 2016), alprazolam (Freeman 1986), sertraline plus omega‐3 (Carney 2009), sertraline plus red yeast rice (Divsalar 2018), St John's wort (Li 2005), simvastatin compared to atorvastatin (Abbasi 2015), Xinkeshu (Ma 2019), saffron compared to fluoxetine (Shahmansouri 2014), Shugan Jieyu compared to sertraline (Liu 2016), Bu Xin Qi compared to escitalopram (Wang 2020).

One trial had a 2 x 2 factorial design (CREATE 2007). In accordance with our inclusion criteria, we restricted analyses to the citalopram and CM versus placebo and CM arms of the trial. The IPT plus citalopram plus CM, and IPT plus placebo plus CM arms of the trial were ineligible and are not described further.

The trial size in psychological intervention studies ranged from 15 participants in Doering 2007 to 2481 participants in ENRICHD 2003. In the pharmacological intervention studies, the trial size ranged from 2 participants in ANDROS 2015 to 369 participants in SADHART 2002.

The mean age of participants ranged from 52.6 in Shahmansouri 2014 to 64.0 years in UPBEAT 2012. The percentage of female participants ranged from 10% in Brown 1993 to 56.8% in Shahmansouri 2014. One study was restricted to female participants only (Doering 2007).

Ten studies originated from the USA (Brown 1993; Carney 2009; Dao 2011; Doering 2007; ENRICHD 2003; Freedland 2009; Freeman 1986; McLaughlin 2005; Roose 1998; UPBEAT 2012), eight from China (Fang 2003; Li 2005; Liu 1999; Liu 2016; Ma 2019; Tian 2016; Wang 2020; Yang 2019), four from Iran (Abbasi 2015; Divsalar 2018; Shahmansouri 2014; Zarea 2014), three from Germany (Barth 2005; SPIRR‐CAD 2011; WIDeCAD 2017), two from Canada (CREATE 2007; McFarlane 2001), two from the Netherlands (MIND‐IT 2007; Strik 2000), two from Italy (Pizzi 2009; TREATED‐ACS 2020), one from Australia (MoodCare 2011), one from Korea (EsDEPACS 2014), one from France (ANDROS 2015), and one from Sweden (U‐CARE 2018). Two studies were performed across multiple sites in different countries, taking place in the USA, Europe, Canada, and Australia in SADHART 2002 and Denmark, Estonia, and Norway in Kennedy 2005.

Sixteen studies investigated individuals with MI or acute coronary syndromes (ANDROS 2015; ENRICHD 2003; EsDEPACS 2014; Fang 2003; Kennedy 2005; Liu 1999; Liu 2016; McFarlane 2001; McLaughlin 2005; MIND‐IT 2007; MoodCare 2011; SADHART 2002; Strik 2000; Tian 2016; TREATED‐ACS 2020; U‐CARE 2018). Twelve trials studied diverse CAD populations comprising MI, angina pectoris, and patients undergoing cardiac procedures (Barth 2005; Brown 1993; Carney 2009; CREATE 2007; Ma 2019; Pizzi 2009; Roose 1998; SPIRR‐CAD 2011; UPBEAT 2012; Wang 2020; WIDeCAD 2017; Yang 2019). Seven trials investigated patients awaiting or after CABG (Abbasi 2015; Dao 2011; Doering 2007; Freedland 2009; Freeman 1986; Li 2005; Zarea 2014), and two trials investigated patients after PCI (Divsalar 2018; Shahmansouri 2014).

We also identified 17 ongoing trials (Ahmadi 2018; Ardakani 2020; COMBAT‐DS 2021; eMindYourHeart 2021; Firouzjaei 2017; Geng 2018; Hamzehpour 2020; Irfan 2020; Jazayeri 2017; Luberto 2021; Ma 2014; Mohammadian 2018; Moudi 2016; Qiaoning 2019; Sourizahi 2017; Wang 2015; Yang 2020). Three studies are awaiting classification, two of which were identified as conference abstracts in our search of the databases, without any contact information available (Ahangarezaiezadeh 2017; Cai 2012; Gu 2017).

Excluded studies

A total of 96 studies (118 articles) that appeared to be relevant to the review were excluded after careful examination of eligibility criteria (see Characteristics of excluded studies for reasons for exclusion). Sixteen studies (21 references) were excluded in the previous review reported by Baumeister 2011c, and 80 studies (97 references) were excluded from the 2020 updated literature search.

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias in the included studies varied across studies (see Figure 2; Figure 3). The information available after translating parts of three trials published in Chinese was insufficient to determine risk of bias in these studies (Fang 2003; Li 2005; Liu 1999). We assessed risk of bias for the two trials that were terminated early by the investigators based on information reported in the clinical trial registries (ANDROS 2015; Kennedy 2005).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Twelve trials used an appropriately generated and adequately concealed randomisation procedure (Abbasi 2015; Barth 2005; Carney 2009; CREATE 2007; Divsalar 2018; ENRICHD 2003; EsDEPACS 2014; Freedland 2009; MoodCare 2011; Shahmansouri 2014; SPIRR‐CAD 2011; UPBEAT 2012). The generation of the randomisation sequence appeared to be appropriate in eight trials; however, they did not sufficiently describe the concealment of the allocation, Dao 2011; Liu 2016; MIND‐IT 2007; Roose 1998; U‐CARE 2018; WIDeCAD 2017; Yang 2019, or failed to conceal the allocation adequately (McLaughlin 2005). Two trials used an inappropriate randomisation procedure and provided insufficient information on concealment (Ma 2019; Zarea 2014). One trial described a sufficient sequence generation but was an open‐label trial (Wang 2020). Details regarding sequence generation and allocation concealment were unclear for the remaining 14 trials (ANDROS 2015; Brown 1993; Doering 2007; Fang 2003; Freeman 1986; Kennedy 2005; Li 2005; Liu 1999; McFarlane 2001; Pizzi 2009; SADHART 2002; Strik 2000; Tian 2016; TREATED‐ACS 2020).

Blinding

No trial of psychological interventions utilised an attention‐control design, thus we judged participants in all psychological intervention trials as unblinded to treatment allocation. The outcome assessor was blinded in seven psychological intervention trials (Barth 2005; Doering 2007; Freedland 2009; MoodCare 2011; SPIRR‐CAD 2011; TREATED‐ACS 2020; Yang 2019). Seven trials did not report sufficient details regarding blinding to make a judgement of low or high risk (Brown 1993; Dao 2011; ENRICHD 2003; Fang 2003; U‐CARE 2018; WIDeCAD 2017; Zarea 2014). We assessed one psychological trial as high risk and unblinded, as the outcome was assessed using patient self‐report without sufficient information regarding blinding (McLaughlin 2005).

In six pharmacological trials blinding was adequately realised and described (Abbasi 2015; CREATE 2007; Divsalar 2018; EsDEPACS 2014; Shahmansouri 2014; UPBEAT 2012). Four pharmacological trials reported using a double‐blind method but did not describe who was blinded (MIND‐IT 2007; Roose 1998; SADHART 2002; Strik 2000). One trial was described as open‐label trial and hence unblinded (Wang 2020). The remaining 11 trials did not report sufficient information regarding blinding of staff, participants, and outcome assessors (ANDROS 2015; Carney 2009; Freeman 1986; Kennedy 2005; Li 2005; Liu 1999; Liu 2016; Ma 2019; McFarlane 2001; Pizzi 2009; Tian 2016).

Incomplete outcome data

Fourteen trials provided intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses for primary outcomes (Carney 2009; CREATE 2007; Divsalar 2018; Freedland 2009; MIND‐IT 2007; MoodCare 2011; Roose 1998; SADHART 2002; SPIRR‐CAD 2011; Strik 2000; TREATED‐ACS 2020; UPBEAT 2012; WIDeCAD 2017; Yang 2019). One trial reported both ITT and per‐protocol analyses simultaneously (SPIRR‐CAD 2011). Depression outcomes were analysed per‐protocol in two trials that reported cardiovascular mortality and cardiac events as ITT (ENRICHD 2003; U‐CARE 2018). Conversely, Strik 2000 reported ITT analyses for depression outcomes and per‐protocol analyses for cardiac events, cardiovascular vital signs, and ECG waves. Fourteen trials reported per‐protocol analyses (Abbasi 2015; Barth 2005; Brown 1993; Doering 2007; EsDEPACS 2014; Freeman 1986; Kennedy 2005; Ma 2019; McFarlane 2001; McLaughlin 2005; Pizzi 2009; Shahmansouri 2014; Tian 2016; Wang 2020). The remaining seven studies provided insufficient information to make a determination (ANDROS 2015; Dao 2011; Fang 2003; Li 2005; Liu 1999; Liu 2016; Zarea 2014).

Selective reporting

We judged eight studies as free of selective reporting based on the comparison of outcomes reported in published study protocols, methods sections, and original papers (CREATE 2007; EsDEPACS 2014; Freedland 2009; MoodCare 2011; Shahmansouri 2014; TREATED‐ACS 2020; U‐CARE 2018; WIDeCAD 2017). Three trials have as yet not reported the results of all the outcomes mentioned in published protocols (Carney 2009; MIND‐IT 2007; SPIRR‐CAD 2011). We assessed four trials as high risk of bias due to incomplete or inadequate outcome reporting (ENRICHD 2003; Kennedy 2005; Ma 2019; Strik 2000). Furthermore, in UPBEAT 2012, we rated selective reporting as unclear risk bias, as measures of variance (standard deviation (SD) or standard error (SE)) were not reported, and P values were reported for active treatment (sertraline group, exercise group), thereby combining two separate interventions. No published or unpublished trial protocols were available other than trial registries for the remaining 21 trials (Abbasi 2015; ANDROS 2015; Barth 2005; Brown 1993; Dao 2011; Divsalar 2018; Doering 2007; Fang 2003; Freeman 1986; Li 2005; Liu 1999; Liu 2016; McFarlane 2001; McLaughlin 2005; Pizzi 2009; Roose 1998; SADHART 2002; Tian 2016; Wang 2020; Yang 2019; Zarea 2014), thus it remains unclear whether or not there is a risk of selective reporting in these trials.

Other potential sources of bias

We judged eight studies as free of other sources of bias (Abbasi 2015; CREATE 2007; EsDEPACS 2014; Freedland 2009; Pizzi 2009; Shahmansouri 2014; Strik 2000; UPBEAT 2012). The risk of other sources of bias remains unclear for the three trials translated from Chinese (Fang 2003; Li 2005; Liu 1999). Ten psychotherapy studies may exhibit performance bias because the adherence of therapists in the treatment group was unclear (Barth 2005; Brown 1993; Doering 2007; McLaughlin 2005; TREATED‐ACS 2020; U‐CARE 2018; WIDeCAD 2017; Yang 2019; Zarea 2014), or was undertaken differently from the protocol (MoodCare 2011). In two trials there was evidence of statistically significant differences between groups at baseline on depression (Brown 1993; MIND‐IT 2007), or differences at baseline were not established (ENRICHD 2003; Wang 2020). In McFarlane 2001 (p 619 and p 620) and McLaughlin 2005 (discrepancy between text and figure of depression score on Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)), results were inconsistently reported. In three trials (Carney 2009; SPIRR‐CAD 2011; U‐CARE 2018), there was a change in the inclusion criteria.

In two trials there was evidence of high risk of bias (selection bias), with eligible participants not recruited (Divsalar 2018; WIDeCAD 2017). There was evidence of high risk of other bias in two internet CBT interventions that were terminated early by investigators with ITT results reported (U‐CARE 2018; WIDeCAD 2017). Similarly, a high risk of other bias was evident in two drug trials terminated early with results not reported (ANDROS 2015), or partially reported per protocol in redacted form (Kennedy 2005). A high risk of other bias was evident in two trials that either did not register the trial (Tian 2016), or did so retrospectively after recruitment had commenced (Ma 2019). A high risk of other bias was evident in two drug trials that included pharmaceutical company employees in the trial design, conduct, analysis, and reporting of results (Roose 1998; SADHART 2002). A high risk of other bias was evident in Liu 2016, where the primary results were reported mid‐treatment.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings table ‐ Psychological treatment compared to control for depression in patients with coronary artery disease.

| Psychological treatment compared to control for depression in patients with coronary artery disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: health problem or population Setting: cardiology in‐ and outpatient Intervention: Psychological treatment Comparison: Control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with Control | Risk with Psychological treatment | |||||

| Depression symptoms ‐ short‐term assessed with: objective and self‐reported measures of depression symptoms, higher scores indicate more severe symptoms | ‐ | SMD 0.55 SD lower (0.92 lower to 0.19 lower) | ‐ | 1226 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | There is low certainty evidence that psychological treatment may result in a moderate reduction in depression symptoms at the end of treatment. |

| Depression remission ‐ short term assessed with: below cut‐points on objective and self‐report measures of depression | 319 per 1000 | 486 per 1000 (267 to 708) | OR 2.02 (0.78 to 5.19) | 862 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | There is low certainty evidence that psychological treatment may result in no difference in depression remission at the end of treatment. |

| All‐cause mortality ‐ short‐term assessed with: mortality records | 25 per 1000 | 8 per 1000 (1 to 50) | OR 0.31 (0.05 to 2.02) | 324 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd,e | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of psychological treatment on all‐cause mortality at the end of treatment. |

| Cardiovascular mortality ‐ long‐term assessed with: cause of death according to standardised criteria on mortality records | 85 per 1000 | 72 per 1000 (54 to 93) | OR 0.83 (0.62 to 1.10) | 2720 (2 RCTs) | ‐ | No data for cardiovascular mortality at end of treatment in trials comparing psychological interventions versus usual care |

| Myocardial infarction ‐ short term (end of treatment) ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data for occurrence of myocardial infarction at end of treatment in trials comparing psychological interventions versus usual care |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_427596582080189491. | ||||||

a Risk of bias rated down one level ‐ trials that contributed to this outcome were rated as unclear risk of bias b Inconsistency rated down one level ‐ though confidence intervals generally overlapped, there was considerable unexplained statistical heterogeneity c Imprecision rated down one level ‐ confidence intervals encompass an adverse effect to beneficial effect d Risk of bias rated down two levels ‐ most trials that contributed to this outcome were rated as high or unclear risk of bias e Imprecision rated down two levels ‐ sparse events and wide confidence intervals encompass an adverse effect to beneficial effect

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings table ‐ Psychological treatment 1 compared to psychological treatment 2 for depression in patients with coronary artery disease.

| Psychological treatment 1 compared to psychological treatment 2 for depression in patients with coronary artery disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: health problem or population Setting: cardiology outpatient settings Intervention: Psychological Treatment 1 Comparison: Psychological Treatment 2 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with Psychological Treatment 2 | Risk with Psychological Treatment 1 | |||||

| Depression symptoms ‐ short term (end of treatment) assessed with: objective and self‐reported measures of depression symptoms; higher scores indicate more severe symptoms | Not pooled | Not pooled | Not pooled | 219 (3 RCTs) | ‐ | No meta‐analysis performed due to clinical heterogeneity. The evidence is very uncertain as to whether different psychological interventions may result in a reduction in depression symptoms at the end of treatment for: cognitive‐behavioural therapy compared to supportive stress management (Freedland 2009); behaviour therapy compared to person‐centred therapy (Brown 1993); cognitive‐behavioural therapy and well‐being therapy compared to clinical management (TREATED‐ACS 2020). |

| Depression remission ‐ short term (end of treatment) assessed with: below cut‐off on Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression | 571 per 1000 | 707 per 1000 (493 to 857) | OR 1.81 (0.73 to 4.50) | 83 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | There is low certainty evidence from one trial that cognitive‐behavioural therapy may result in no difference in depression remission at the end of treatment compared to supportive stress management (Freedland 2009). |

| All‐cause mortality ‐ short term (end of treatment) ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data for all‐cause mortality at end of treatment in trials comparing psychological intervention versus another psychological intervention/clinical management |

| Cardiovascular mortality ‐ short term (end of treatment) ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data for cardiovascular mortality at end of treatment in trials comparing psychological intervention versus another psychological intervention/clinical management |

| Myocardial infarction ‐ short term (end of treatment) ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data for the occurrence of myocardial infarction at end of treatment in trials comparing psychological intervention versus another psychological intervention/clinical management |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_427665509108780589. | ||||||

a Imprecision rated down two levels ‐ wide confidence intervals from one trial encompass an adverse effect to beneficial effect

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings table ‐ Pharmacological treatment compared to placebo for depression in patients with coronary artery disease.

| Pharmacological treatment compared to placebo for depression in patients with coronary artery disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: health problem or population Setting: cardiology in‐ and outpatient settings Intervention: Pharmacological Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with Placebo | Risk with Pharmacological | |||||

| Depression symptoms ‐ short term assessed with: objective and self‐reported measures of depression; higher scores indicate more severe symptoms | ‐ | SMD 0.83 lower (1.33 lower to 0.32 lower) | ‐ | 750 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | There is low certainty evidence that pharmacological intervention may result in a large reduction in depression symptoms at the end of treatment |

| Depression remission ‐ short term assessed with: below cut‐point on objective measure of depression (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression) | 323 per 1000 | 496 per 1000 (412 to 580) | OR 2.06 (1.47 to 2.89) | 646 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | There is moderate certainty evidence that pharmacological intervention probably results in a moderate to large increase in depression remission at the end of treatment. |

| All‐cause mortality ‐ short term assessed with: mortality records | 36 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (4 to 53) | OR 0.38 (0.10 to 1.47) | 437 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of pharmacological intervention on all‐cause mortality at the end of treatment. In addition to the pooled results, data could not be extracted from 2 studies where no deaths occurred and from 1 trial which remained unclear. |

| Cardiovascular mortality ‐ short term (end of treatment) ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data for cardiovascular mortality at end of treatment in trials comparing pharmacological intervention versus placebo |

| Myocardial infarction ‐ short term assessed with: standardised criteria for fatal or non‐fatal myocardial infarction | 22 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (6 to 45) | OR 0.74 (0.26 to 2.09) | 728 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of pharmacological intervention on myocardial infarction at the end of treatment. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_427666962988765745. | ||||||

a Risk of bias rated down one level ‐ trials that contributed to this outcome were rated as unclear or high risk of bias b Inconsistency rated down one level ‐ though confidence intervals generally overlapped, there was considerable unexplained statistical heterogeneity c Imprecision rated down two levels ‐ sparse events and wide confidence intervals encompass an adverse effect to beneficial effect

Summary of findings 4. Summary of findings table ‐ Pharmacological treatment 1 compared to pharmacological treatment 2 for depression in patients with coronary artery disease.

| Pharmacological treatment 1 compared to pharmacological treatment 2 for depression in patients with coronary artery disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: health problem or population Setting: cardiology in‐ and outpatient settings Intervention: Pharmacological intervention 1 Comparison: Pharmacological intervention 2 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with Pharmacological intervention 2 | Risk with Pharmacological intervention 1 | |||||