Graphical abstract

Keywords: COVID-19, Face masks, Wearing comfortability, Anti-pathogen functionality, Electrothermal conversion

Abstract

Wearing surgical masks remains the most effective protective measure against COVID-19 before mass vaccination, but insufficient comfortability and low antibacterial/antiviral activities accelerate the replacement frequency of surgical masks, resulting in large amounts of medical waste. To solve this problem, we report new nanofiber membrane masks with outstanding comfortability and anti-pathogen functionality prepared using fluorinated carbon nanofibers/carbon fiber (F-CNFs/CF). This was used to replace commercial polypropylene (PP) nonwovens as the core layer of face masks. The through-plane and in-plane thermal conductivity of commercial PP nonwovens were only 0.12 and 0.20 W/m K, but the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes reached 0.62 and 5.23 W/m K, which represent enhancements of 380% and 2523%, respectively. The surface temperature of the PP surgical masks was 23.9 ℃ when the wearing time was 15 min, while the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks reached 27.3 ℃, displaying stronger heat dissipation. Moreover, the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes displayed excellent electrical conductivity and produced a high-temperature layer that killed viruses and bacteria in the masks. The surface temperature of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks reached 69.2 ℃ after being connected to a portable power source for 60 s. Their antibacterial rates were 97.9% and 98.6% against E. coli and S. aureus, respectively, after being connected to a portable power source for 30 min.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 was caused by a novel infectious virus [1], [2]. This pathogen was renamed as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by the professional organization [3], [4], [5]. By the end of May 2021, more than 160 million people were infected with COVID-19, resulting in more than 3.4 million deaths [6]. Vaccination is a critical measure for controlling COVID-19[7], but before mass vaccination is achieved, wearing personal respiratory protection equipment remains the most effective measure for reducing the risk of viral infection [8], [9].

Surgical masks have a high performance and low cost and are the most frequently used face masks during COVID-19[10], [11]. People must wear face masks for increasingly longer periods. Front-line workers, such as doctors, nurses, customs quarantine staff, airport staff, etc., are often in close contact with patients that carry the virus; therefore, they must wear face masks all day for several days each week. However, the comfortability of surgical masks is poor. In hot weather, most people feel uncomfortably hot after wearing surgical masks for a long time [8]. To relieve this uncomfortable feeling, people will often touch or take off their face masks, which increases the risk of infection [12]. The poor thermal conductivity of surgical masks is one of the main causes of uncomfortable feelings for users. Polypropylene (PP) melt nonwovens are the most important component in the surgical masks, which have a large number of micropores and randomly distributed monofilaments [13], [14], [15]. Similar to most polymers, PP is a poor conductor of heat, so the thermal conductivity of surgical masks is also low [16], [17]. In addition, the thermal insulation of surgical masks is also insufficient in cold weather. People living in cold regions wear a scarf to replace face masks, but scarfs do not effectively intercept bacteria or viruses.

Another issue is that large amounts of medical waste are produced by surgical masks [18], [19]. It has been estimated that a monthly use of 129 billion face masks is necessary to protect humans worldwide, and this number continues to increase [20]. Surgical masks effectively intercept bacteria and viruses, but they do not possess antibacterial or antiviral activity. Bacteria and viruses adhere to surgical masks, which threatens people's health. To maintain a clean respiratory environment, people must frequently replace face masks, resulting in large amounts of medical plastic wastes. Due to the persistence and high contagiousness of SARS-CoV-2, most countries classify waste face masks as infectious, requiring their incineration at high temperatures, followed by landfilling of the residual ash [21], [22]; however, these treatment modalities intensify the greenhouse effect and release potentially dangerous compounds [23]. Zhong et al. [24] adopted a laser method to create few-layered graphene onto a surgical mask. The introduction of graphene formed a high-temperature layer that killed the virus by photothermal conversion. Li et al. [25] first fabricated polyvinyl alcohol, poly (ethylene oxide), and cellulose nanofiber masks, followed by the deposition of a mixture of nitrogen-doped TiO2 and TiO2. The masks reached 100% bacteria disinfection under irradiation in natural sunlight for 10 min. Sio et al. [26] outlined how to realize non-disposable and highly comfortable respirators capable of light-triggered self-disinfection by combining bioactive nanofiber properties with stimuli-responsive nanomaterials. Karmacharya et al. [27] discussed the manufacturing, practical applications, and anti-COVID-19 performance of novel masks. Melayil et al. [28] investigated interactions of droplets over the most used surgical masks and studied the wetting signature, adhesion, and impact dynamics of water droplets and microbe-laden droplets on both sides of the mask. However, these reported masks are difficult to solve the above problems simultaneously.

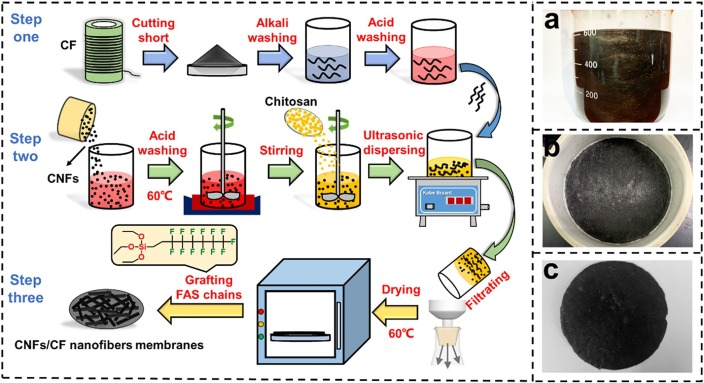

In this work, we report a multifunctional face mask with excellent comfortability and anti-pathogen functionality, composed of carbon fibers (CF) and carbon nanofibers (CNFs). As shown in Fig. 1 , the preparation process included three steps: (1) CFs with a clean surface were prepared by acid washing and alkali washing; (2) The CFs, CNFs, and chitosan hybrid suspension were prepared by solution blending; (3) the hybrid suspension was filtered and dried to afford F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. Then, 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorodecyltrimethoxysilane (FAS) chains were grafted onto the nanofiber membranes to prepare hydrophobic F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. The F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes exhibited a better heat-dissipation efficiency than commercial PP nonwovens, providing users with a more comfortable breathing environment. The F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes also formed a high-temperature layer that killed viruses and bacteria in the masks when connected to a portable power source.

Fig. 1.

Preparation process of the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Materials

Carbon fibers (CF) were supplied by the High-Performance Fiber Research Group, Wuhan Textile University). Carbon nanofibers (CNFs) with an average particle size of 100 nm were purchased from Chengdu Jiacai Technology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). 1H,1H,2H,2H-Perfluorodecyltrimethoxysilane (FAS) was purchased from Adamas Reagent, Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Formic acid, acetic acid, anhydrous ethanol, sodium hydroxide, nitric acid, hydrochloric acid, and chitosan were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd. Deionized water was used throughout the experiments.

2.2. Preparation of short chopped CF

First, the continuous CF was cut off in short fibers of 2 mm length by using a fixed length cutter. Second, the short CF was slowly added to a 10 vol% NaOH aqueous solution. After immersing in NaOH aqueous solution for 1 h, the short CF was rinsed with deionized water several times to completely remove the residual alkali liquor on the surface of the CF. Finally, the short CF was added to the 20 vol% nitric acid solution and soaked at 37 °C for 1 h, and then the short CF was also rinsed with deionized water several times to obtain the short CF with a surface clean [29].

2.3. Preparation of CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes

First, a certain amount of CNFs was added to the 40 vol% nitric acid solution, and then the mixture solution was heated to 60 ℃. After immersing for 2 h, the CNFs were separated from the acid solution and rinse with deionized water several times [30]. Subsequently, the CNFs with a clean surface were added into 100 mL of chitosan solution; the concentration of chitosan solution was 0.5 wt%. Then, the solution was stirred continuously for 12 h to obtain the CNFs/chitosan hybrid solution (Fig. 1a). Finally, a certain amount of short CF was added to the CNFs/chitosan hybrid solution. After ultrasonic dispersion for 12 h, the CNFs/CF hybrid solution was filtrated, washed with deionized water, and dried to prepare the CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes (Fig. 1b). Chitosan was used as adhesive to enhance the bonding strength between fibers in the CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. The dosage of short CF in CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes was a constant value of 1 g; the dosages of CNFs were 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, and 0.2 g, respectively. The thickness of CF, F-CNFs/CF-1, F-CNFs/CF-2, F-CNFs/CF-3, and F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes were shown in Fig. S1.

2.4. Preparation of hydrophobic F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes

Surgical masks have excellent hydrophobicity, which can prevent the droplets or aerogels with viruses from the outside to enter our respiratory tract and lungs, reducing the risk of infection. However, the CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes exhibit high hydrophilicity, they cannot be used to intercept and filtrate droplets and aerogels with the virus. To address this problem, we grafted the FAS on the CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes for improving their hydrophobicity. The preparation process of hydrophobic F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes was as follows: First, an amount of 88 g ethanol and 1.5 g hydrochloric acid were mixed in 10 mL deionized water, followed by the addition of 0.5 g FAS solution to prepare the FAS modification solution [31]. Subsequently, the prepared CNFs/CF nanofiber membrane was soaked in FAS modification solution for 5 min. Finally, the wet samples were dried at 80 ℃ to obtain F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes.

2.5. Characterization

The chemical composition and electronic states of all samples were analyzed by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy utilizing a Nicolet 380 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) utilizing an Escalab 250Xi spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). The surface morphology and microstructure of the samples were characterized by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) using a Nova NanoSEM 450 scanning electron microscope (FEI Co., Hillsboro, OR). The contact angle measurement was performed using an DSA30 drop shape analysis system (Kruss, Hamburg, Germany). The pore diameter distribution were measured by an automatic capillary flow porometer (PMI, CFP-1500- AEXL, USA). The filtration efficiency of all samples was tested by an SX-L1056 particle filtration tester (Suxin Environmental Technology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China); the test principle was shown in the Fig. S2. The air permeability of the samples was examined by a YG461G fully automatic air permeability tester (Ningbo Textile Instrument Factory, Ningbo, China). The tensile strength of the samples was tested by an Instron 5966 tensile tester (Instron Corp., Norwood). The surface temperature of the sample was tested by a Testo 875-2i thermal imaging camera (Testo SE and Co., KGaA, Lenzkirch, Germany). The thermal conductivity of the sample was measured by a NETZSCH LFA457 MicroFlash laser-flash thermal conductivity meter (NETZSCH-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany).

2.6. Antibacterial tests

We selected Escherichia coli (E. coli, a Gram-negative bacterium, Carolina #155065A) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus, Gram-positive bacteria, Carolina #155556) as representative microorganisms to evaluate the antibacterial activity of the samples. First, the two strains were cultured in 10 mL of Luria − Bertani broth (LB) for 24 h at 37 °C. An overnight culture of the test strain was diluted in deionized water to yield a concentration of approximately 105 CFU/mL. Then, the four Petri dishes containing the 10 mL bacterial solution were placed on the surface of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks and covered with an insulating cover. After being electrified for 0, 5, 15, and 30 min separately, we removed 2 mL of the bacterial solution from each of the four Petri dishes. After incubation and mild oscillation in an orbital shaker at 37 ℃ for 24 h, the bacterial fluids were diluted and applied to a fresh culture plate of sterile LB agar. Then, everything was cultured at 37 ℃ for 18 h. The antibacterial rate (%) was calculated with the following formula [32]:

| (1) |

where OD refers to the optical density of the bacteria solution at 600 nm, which was measured by an ST-360 micro-plate reader (Kehua Experimental System Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China); OD 0, OD 1, and OD 2 represent the optical densities of the blank, control group, and experimental group, respectively. For each sample, three individual measurements were performed, and the average was reported as the final antibacterial rate.

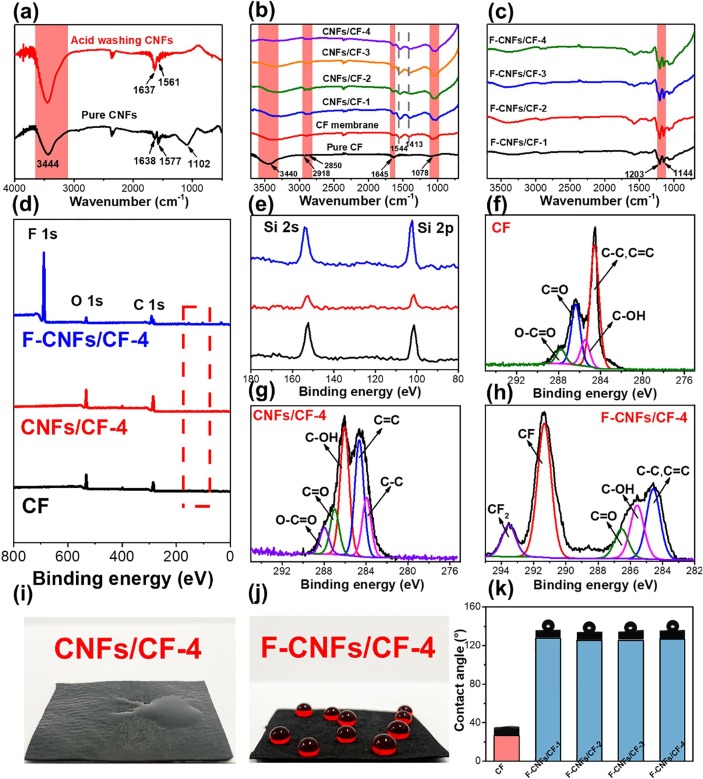

Surgical masks with excellent hydrophobicity can prevent the virus in droplets from entering the respiratory tract and lungs, thus reducing the infection risk. Both CF and CNFs used in this work were hydrophilic; thus, FAS chains were grafted onto the CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes to prepare hydrophobic F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. Fig. 2 a presents the FITR spectra of the CNFs before and after acid washing. Four significant peaks appeared for both pure CNFs and acid-washed CNFs. The wide peak around 3626–3116 cm−1 was assigned to the –OH stretching from an acid group [33]. The two peaks at 1638 and 1577 cm−1 were attributed to conjugated aromatic C = C and quinoid C = O bonds, respectively [34]. The peak located at 1102 cm−1 corresponds to C-O ether stretching [34]. After washing by acid solution, no new absorption peaks were detected, but the –OH absorption peak was stronger than in the pure CNFs spectrum. Fig. 2b provides the FITR spectra of pure CF and CF membrane. In the FITR spectra of pure CF, the peak at 3440 cm−1 is related to the tensile vibration of –OH groups [35]. The peaks at 2918 and 2850 cm−1 were attributed to the –CH2 asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations, respectively [36], [37]. The peak at 1645 cm−1 corresponds to the C = C tensile vibration [38]. The peak at 1078 cm−1 was assigned to the C-O in the carboxyl group [36]. Compared with pure CF, two new absorption peaks at 1544 and 1413 cm−1 in the CF membrane correspond to amide II and the N–H absorption peak of glucosamine [39]. These peaks were derived from chitosan. Remarkably, no new absorption bands were detected in the CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes, and they appear to be the overlapping of the pure CF and CF membrane spectra. Fig. 2c presents the FITR spectra of F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. After processing in FAS solution, two strong peaks appeared at 1203 and 1144 cm−1 in the F-CNFs/CF spectrum, which are attributed to the C-F3 vibrations and Si-O-Si asymmetric stretching vibrations, respectively [40].

Fig. 2.

(a) FTIR spectra of the pure CNFs and acid-washed CNFs. (b) FTIR spectra of the pure CF, CF membrane, and CNFs/CF. (c) FTIR spectra of the F-CNFs/CF. (d) Full-scan XPS spectra of pristine CF, CNFs/CF, and F-CNFs/CF-4. (e) Enlargement of the Si spectrum. (e) N 1 s core-level spectra of pristine h-BN. (f) C 1 s core-level spectra of pristine CF. (g) C 1 s core-level spectra of CNFs/CF. (h) C 1 s core-level spectra of pristine F-CNFs/CF-4. (i) Hydrophilic test of CNFs/CF. (j) Hydrophilic test of F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. (k) Contact angles of CF membrane and F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes.

XPS was used to analyze the surface states and components of the as-prepared samples. In the full-scan XPS spectrum (Fig. 2d), only C and O elements were found in the curves of pure CF and F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes; however, after processing by FAS solution, an intense peak appeared at 687.8 eV in the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes, which corresponded to F 1 s. Fig. 2e is an enlarged view of the red box region in Fig. 2d, which confirmed the existence of Si atoms. Unexpectedly, Si atoms were detected in all three samples; thus, Si cannot be used to prove that FAS chains existed in the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes. Fitting of the C 1 s core-level spectra of the three samples was conducted by using Casa XPS analysis software. In the C 1 s core-level spectra of pure CF (Fig. 1f), the C 1 s peak was fitted to four peaks at 284.6, 285.5, 286.3, and 287.8 eV, which were attributed to C–C/C = C, C-OH, C = O, and O-C = O groups, respectively. These groups are consistent with pure CF in the C 1 s core-level spectra of the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes (Fig. 2g). As shown in Fig. 2h, after processing in FAS solution, two new characteristic peaks at 291.4 and 293.6 eV appeared in the curve of the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes, which correspond to C-F and F-C-F [41]. Table 1 provides the surface element contents of the three samples. It can be seen from the table that CF and F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes contained the same elements, including O, C, N, and Si. The trace N atoms were derived from chitosan; however, the C content on the surface of F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes was much higher than that of pure CF. The surface elements of F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes changed compared with those of CF and CNFs/CF. The O content decreased significantly, and many new F and C atoms appeared. The FITR and XPS results confirm that the FAS chains were successfully grafted onto the surface of the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes.

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of pure CF, F-CNFs/CF-4, and F-CNFs/CF-4.

| Samples | Elemental analysis (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | C | N | Si | F | |

| CF | 24.16 | 66.06 | 4.27 | 5.50 | 0 |

| CNFs/CF | 19.54 | 75.69 | 3.69 | 1.28 | 0 |

| F-CNFs/CF | 5.44 | 45.18 | 0.09 | 4.71 | 44.57 |

Subsequently, water droplets were dropped onto the surface of F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes to assess their hydrophobicity, using the unmodified CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes as a control group. Fig. 2(i) provides a photo of the CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes during the hydrophobicity test. Once in contact with the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membrane, water droplets quickly diffused and penetrated the surface, indicating that the unmodified F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes were highly hydrophilic. In contrast, as shown in Fig. 2(j), water droplets remained on the surface of the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes, confirming that FAS grafting endowed the nanofiber membranes with hydrophobicity. Subsequently, we evaluated the hydrophobicity of the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes by measuring their water contact angle. As shown in Fig. 2(k), the water contact angle of the CF membrane was 26.5°, while those of the four F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes exceeded 125°, confirming the great hydrophobicity of the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes.

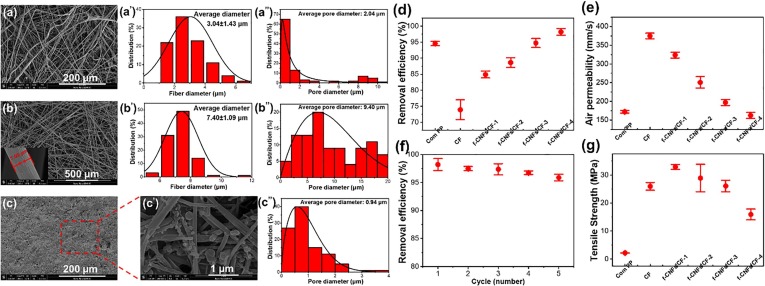

Fig. 3(a) and 3(b) present the microstructures of commercial PP nonwovens and CF membranes. They consist of randomly stacked fibers, but the PP fibers in the commercial PP nonwovens are relatively curly and have different shapes, while the carbon fibers in the CF membrane are straight and have regular shapes. Fig. 3(a’) and 3(b’) provide the fiber diameter distribution of commercial PP nonwovens and homemade CF membranes. The fiber diameter distribution of commercial PP nonwovens is in the range of 1–7 µm, and their average diameter is 3.04 ± 1.43 µm. Compared with commercial PP nonwovens, the diameter distribution range of the CF membrane is narrower and is mainly concentrated at 5–10 µm, with an average diameter of 7.41 ± 1.09 µm. Fig. 3(a’’) and 3(b’’) show the pore size distribution of commercial PP nonwovens and homemade CF membranes. For commercial PP nonwovens, most pores were 0–1 µm with an average pore size of 2.04 µm. In contrast, the CF membrane exhibited a wide pore size distribution, mainly concentrated at 2–20 µm with an average pore size of 9.40 µm. Fig. 3(c) presents the microstructure of F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes. After CNFs loading, no pores were observed at low magnification. In the high-magnification image (Fig. 3 (c’)), nano-sized CNFs are stacked on the surface of the CF substrate, covering the larger pores between the carbon fibers. Fig. 3(c’’) shows the pore size distribution of the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes. Compared with commercial PP nonwovens, the pore size distribution of the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes is narrower and mainly concentrated in the range of 0.5–1 µm. Statistical data showed that the average pore size of F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes was only 0.94 µm.

Fig. 3.

(a) Microstructure of commercial PP nonwovens; (a’) Fiber diameter distribution of commercial PP nonwoven; (a’’) Pore diameter distribution of commercial PP nonwovens. (b) Microstructure of the CF membrane; (b’) Fiber diameter distribution of the CF membrane; (b’’) Pore diameter distribution of the CF membrane; (c) and (c’) Microstructure of F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes; (c’’) Pore diameter distribution of F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes. (d) The PM2.5 removal efficiency of commercial PP nonwovens, CF membrane, and F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. (e) The air permeability of commercial PP nonwovens, CF membrane, and F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. (f) The PM2.5 removal efficiency of the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes after five recycling usages. (g) Tensile strength of commercial PP nonwovens, CF membrane, and F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes.

Fig. 3d provides the PM2.5 filtration efficiency of commercial PP nonwovens, CF membrane, and F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. The PM2.5 filtration efficiency of commercial PP nonwovens was 94.7%, while the filtration efficiency of the CF membrane for PM2.5 was only 74.1%. The filtration efficiency of a fiber membrane mainly depends on its pore size and pore size distribution [42]. Compared with the CF membrane, commercial PP nonwovens have a narrower pore size distribution and a lower average pore size; thus, their PM2.5 filtration efficiency is higher than the CF membrane. After CNFs loading, the PM2.5 filtration efficiency of the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes was significantly improved. The PM2.5 filtration efficiency of the F-CNFs/CF-1 nanofiber membrane was 95.8%, while that of F-CNFs/CF-4 reached 98.2%. By comparing Fig. 3b and 3c, the introduced CNFs covered the large pores between carbon fibers and evolved into many ultrafine micropores (<1µm); thus, the PM2.5 filtration efficiency of the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes was improved significantly. However, when the dosage of CNFs was low (0.05 g), they could not cover all pores (Fig. S4a). As the CNFs dosage increased, the larger pores were completely covered, and many ultrafine microporous structures formed (Fig. S4b-S4d). Thereby, the filtration efficiency of the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes gradually improved upon increasing the CNFs dosage.

Air permeability is one of the key indexes used to evaluate face masks. If the air permeability is poor, the mask will provide large respiratory resistance and have no practical application value. As shown in Fig. 3e, the air permeability of commercial PP nonwovens was 172.1 mm/s, while that of the homemade CF membrane reached 374.8 mm/s. Compared with commercial PP nonwovens, the CF membrane had a larger pore size and wider pore size distribution; therefore, the resistance was lower when airflow passed through the CF membrane, resulting in higher air permeability. After the CNFs were introduced, the air permeability of the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes decreased slowly upon increasing the filling content. When the filling content of CNFs was 0.2 g, the air permeability of the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes was 150.3 mm/s, which was slightly lower than the commercial PP nonwovens. Because the average pore size of the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes was only 0.94 µm, they created a higher resistance to airflow, resulting in a decrease in the air permeability; however, the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes kept their abundant ultrafine micropores at high loadings; thus, their air permeability was maintained at an ideal level.

To evaluate the reusability of F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes, we measured their PM2.5 filtration efficiency after five cycles. Before every cycle, the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membrane was immersed in deionized water, ultrasonically cleaned for 30 min, and then dried at a low temperature. As shown in Fig. 3f, the PM2.5 filtration efficiency curve of the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes did not significantly decrease. After five usage cycles, their filtration efficiency remained at 95.9%, confirming the outstanding reusability of the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. Fig. 3g provides the tensile strength of commercial PP nonwovens, CF membrane, and F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. Although mechanical strength is not the most critical indicator of a face mask, it can affect their service life and structural stability. As shown in the figure, the tensile strength of commercial PP nonwovens was 2.2 MPa, while that of the CF membrane was significantly higher, at 4.22 MPa. Because carbon fibers have greater mechanical strength than the PP fibers, and because the carbon fibers are bonded through chitosan, their bonding strength is superior to that of the commercial PP nonwovens, which have a loose structure; therefore, the tensile strength of the CF membrane was much higher than that of the commercial PP nonwovens. The tensile strength of the F-CNFs/CF nanofibers was further improved after CNFs loading. When the CNFs loading increased from 0.05 g to 0.20 g, the tensile strength of the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membrane increased from 4.78 MPa to 5.11 MPa. The CNFs connected adjacent carbon fibers in the CF membrane which increased the slip resistance between carbon fibers, thereby improving the tensile strength of F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. In addition, the influence of moisture on the mechanical properties and filtration performance of the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes was investigated, and the results are shown in Fig. S5.

We measured the through-plane (K ⊥) and in-plane (K ∥) thermal conductivities of commercial PP nonwovens, homemade CF membrane, and F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes, and the results are shown in Fig. 4 a and 4b. As shown in Fig. 4a, the K ⊥ of the commercial PP nonwovens was 0.12 W/m K, and that of the homemade CF membrane was slightly higher, which was 0.13 W/m K. After CNFs loading, the K ⊥ of the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes continued to increase. When the CNFs loading was 0.20 g, the K ⊥ of the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes reached 0.62 W/m K, an enhancement of 380% compared with commercial PP nonwovens. Fig. 4b presents the K ∥ of all samples. The K ∥ of commercial PP nonwovens was 0.20 W/m K, and that of the CF membrane was 0.52 W/m K. Since the thermal conductivity of carbon fibers is strongly anisotropic, the thermal conductivity of parallel carbon fibers was significantly higher than in the vertical direction. The vertical direction of the CF membrane was the vertical direction of the carbon fibers, and their parallel direction corresponded to the parallel direction of the carbon fibers; therefore, the K ∥ of the CF membrane was higher than the K⊥. After CNFs loading, the K∥ of F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes also gradually increased. When the CNFs loading increased from 0.05 g to 0.20 g, the K ∥ of the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes increased from 1.20 W/m K to 5.23 W/m K.

Fig. 4.

(a) Thru-plane thermal conductivity of commercial PP nonwovens, CF membrane, and F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. (b) In-plane thermal conductivity of commercial PP nonwovens, CF membrane, and F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. (c) Surface morphology of CF membrane. (d) and (d’) Surface morphology of F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes. (e) and (e’) Cross-section morphology of CF membrane. (e’’) Simplified model of CF membrane. (f) and (f’) Cross-section morphology of F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes. (f’’) Simplified model of F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes.

Fig. 4c-4f provide the SEM images of the surface and cross-section of the CF membrane and F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes. Many pores emerged in adjacent carbon fibers of the CF membrane (Fig. 4c), which did not facilitate heat diffusion. After CNFs loading, as shown in Fig. 4d and 4d’, adjacent carbon fibers were connected by CNFs to form a complete network, resulting in a significant improvement in the K ⊥ of the nanofiber membranes. Fig. 4e and 4e’ show that the cross-section of the CF membrane was composed of multilayered carbon fibers that were loosely stacked with few connection points. As shown in the simplified diagram of the CF membrane (Fig. 4e’’), the carbon fibers in the CF membrane did not form a continuous network. Consequently, heat could not be quickly transferred to the other side when one side of the CF membrane touched the heat source. Fig. 4f and 4f’ are the cross-section morphologies of F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes. After the introduction of CNFs, adjacent carbon fibers were connected by CNFs and formed a continuous structure. The simplified diagram (Fig. 4f’’) shows that heat continuously diffused in the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes due to the continuous network; therefore, the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes showed a high K ∥.

To investigate the heat-dissipation difference of commercial PP nonwovens, CF membrane, and F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes in practical applications, the surface temperatures of the three samples were measured after different heating times. As shown in Fig. S6a, three samples of the same size were simultaneously placed on an 80 ℃ heating table. Fig. S6b shows infrared thermal images of the three samples under different testing times. Compared with the other two samples, the color map of the surface temperature of the commercial PP nonwovens was significantly different. Their surface temperature was in the low-temperature zone. We utilized IRSoft software to analyze the surface temperature distribution of the three samples and calculate their average surface temperature. As shown in Fig. S6c, the surface temperatures of commercial PP nonwovens were much lower than those of the homemade CF membrane and F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. When the test time was 60 s, the surface temperatures of commercial PP nonwovens, CF membrane, and F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes were 46.7, 61.9, and 65.4 ℃, showing that F-CNFs/CF exhibited the best heat-dissipation efficiency.

Fig. 5a is a schematic diagram of the structure of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous mask, which is similar to surgical masks and is composed of three parts: an inner layer, a core layer, and an external layer. The inner layer is also called the hygroscopic layer and is made of medical gauze or hydrophilic nonwovens. The external layer of the mask is a hydrophobic layer, which is usually made of a thinner PP nonwoven. The core layer is the most critical component used to cut off and filter dust, bacteria, and viruses. In this paper, the core layer of the mask was F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes. We recorded the temperatures and thermal images of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks at different times using an IR thermal imager, and the surgical masks were measured as the control group. As shown in Fig. 5b, the inset image on the right bottom of each picture is the statistical result of the zone temperature. At different test times, the surface temperature and color maps of F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks displayed higher temperatures than the commercial PP surgical masks. As shown in Fig. 5c, the surgical masks had temperatures of 21.5, 23.0, and 23.9 ℃ when the wearing time was 5, 10, and 15 min. The average surface temperature of the masks reached 24.2, 26.4, and 27.3 ℃, showing that their surface temperatures were significantly higher than the surgical masks, confirming that the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks had better heat dissipation than surgical masks.

Fig. 5.

(a) Schematic diagram of the structure of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks. (b) Thermal images of commercial PP surgical masks and F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks. (c) Surface temperatures of commercial PP surgical masks and F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks at different times.

Spraying 75% ethanol or disinfectant is the primary antiviral method for surgical masks, but this also destroys the fibrous structure, leading to decreased filtration efficiency [43], [44]. Another method utilizes high temperatures to kill SARS-CoV-2, which hardly affects the fiber structure [45]. Abraham et al. [46] reported that SARS-CoV-2 can be killed by heating within 20 min at 60 ℃, 5 min at 65 ℃, and only 3 min at 75 ℃. The F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes are made of carbon nanofibers and carbon fibers with excellent electrical conductivity, and they could form a high-temperature layer to kill the virus by connecting them to a power source. As shown in Fig. 6 a, the electrical resistance of the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes was 1.7 Ω, as measured by a multimeter. To achieve more precise results, the resistance of F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes was measured by voltammetry by manually applying different voltages to obtain the corresponding current of the tested samples. We then performed a linear fit to the obtained data to determine the resistance of the tested samples. As shown in Fig. 6b, the resistance of the homemade CF membrane was 3.7 Ω. After CNFs loading, the resistance of the F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes gradually decreased. When the CNFs loading was 0.20 g, the resistance of the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes was only 1.19 Ω. The following equation was used to calculate the electrical conductivities (p) of all samples.

| (2) |

where R is the resistance of the sample; A is the area of the sample; l is the thickness of the sample. The measured results are shown in Fig. 6c. The conductivity of CF membrane, F-CNFs/CF-1, F-CNFs/CF-2, F-CNFs/CF-3, and F-CNFs/CF-4 were 54.03, 99.21, 123.85, 145.94, and 167.23 S cm−1, respectively.

Fig. 6.

(a) The resistance of F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes measured by a multimeter; (b) The resistance of F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes measured by voltammetry; (c) Electrical conductivity of CF membrane and F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membranes; (d) Transforming electricity into heat in the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks by connecting them to a portable power source; (e) Surface temperature of F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks after connecting to a portable power source; (f) Schematic diagram of the antiviral principle of F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks.

As shown in Fig. 6d, the F-CNFs/CF-4 nanofiber membrane with the highest conductivity was used as the core layer of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks, and a portable mobile power source was employed to provide electrical energy to the face masks. The output voltage of the mobile power source was 5 V, and the output current was 2 A. Fig. 6e shows the infrared thermal images of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks at different connection times. The surface temperature of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous mask was 48.6 ℃ when the connection time is 10 s. The temperature linearly increased to 59.1 °C at 30 s, and the temperature rose to 69.2 °C within 60 s. The entire electrothermal conversion process is shown in Video 1. Fig. 6f is a schematic diagram of the antiviral principle of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks. When people enter public or densely-populated places, they can wear masks to prevent the virus from entering their respiratory tract. When people are in a safe environment, the masks can convert electrical energy into heat when they are connected to power. Then, the high-temperature layer can kill the virus [46].

Fig. 7a presents a schematic diagram of the antibacterial experiment for the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks. First, the masks were placed on a foam pad. Then, the Petri dish containing the bacterial solution was placed on the surface of masks and covered with an insulating cover. Finally, F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks formed a high-temperature layer to heat the bacterial solution when connected to a power source. We collected and measured the bacteria solution at different periods to evaluate the antibacterial rate of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks. Fig. 7b is a high-resolution photo of the bacterial solution after 30 min. We can observe many droplets on the internal surface of the Petri dish due to the vaporization of the bacterial solution. In the infrared thermal image (Fig. 7c), the temperature of the bacterial solution reached 78.4 ℃ at 30 min, confirming that droplets were produced by the vaporization of the bacterial solution. Fig. 7d presents the antibacterial activity plots of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks for E. coli and S. aureus. As the test time increased, the number of colonies on the agar plate decreased sharply. When the test time reached 30 min, no obvious colonies were observed on the agar plate.

Fig. 7.

(a) Schematic diagram of antibacterial experiment of F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks; (b) Image of heated bacterial solution; (c) IR thermal images of the antibacterial experiment of F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks; (d) Images of the distributions of E. coli and S. aureus colonies on nutrient agar solid plates.

Table 2 shows the antibacterial rate of F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks against E. coli and S. aureus. When the testing time was 5 min, the antibacterial rates of the mask against E. coli and S. aureus were only 12.1 and 13.7%, respectively. Within this period, the bacterial solution was heated by the masks for only a short time; therefore, the temperature of the bacterial solution was low, and the inhibitory effect on bacteria was also weak. In comparison, the antibacterial rates reached 97.9% and 98.6% against E. coli and S. aureus at 30 min. At this time, the bacterial solution was heated to a high temperature by the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks, which led to the protein denaturation of the bacteria and eventually killed them [47], [48], [49].

Table 2.

Antibacterial rates of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks for E. coli and S. aureus.

| Name |

Antibacterial efficiency (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 min | 5 min | 15 min | 30 min | |

| E. coli | 0 | 12.1 | 94.1 | 97.9 |

| S. aureus | 0 | 13.7 | 98.2 | 98.6 |

The electrothermal conversion in F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks can also provide heat for people living in cold areas. As shown in Fig. 8 a, the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks were placed in a low-temperature test box at −11 ℃ after being connected to a portable power bank. Then, we employed an infrared thermal imaging instrument to record the surface temperature of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks at different times, and the results are shown in Fig. 8b and 8c. As shown in Fig. 8c, the red area in the infrared thermal images of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks gradually shrank over time, indicating that the surface temperature of the masks was gradually reduced. The statistical analysis demonstrates that the surface temperature of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks was 37.9 ℃ after 10 min, which is higher than the temperature of the human body. The surface temperature of the masks decreased to 35.6 ℃ at 30 min, and the surface temperature remained at 34.8 ℃ for 60 min.

Fig. 8.

(a) Temperature test and (b) data of F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks connected to a portable power source in a low-temperature environment. (c) IR thermal images of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks after connecting to a portable power source in a low-temperature environment. (d) Diagram of F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous mask resistance during electrothermal measurements. (e) Temperature of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous mask as a function of applied resistance. (f) IR thermal images of F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks at different resistance values.

Since different areas have different ambient temperatures in the cold season, the heating temperature of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks need to be adjustable depending on the practical requirements. As shown in Fig. 8d, a rheostat was connected in series between the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks and the portable power bank to adjust the supplied heat. Fig. 8e presents the surface temperatures of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks connecting resistors with different resistance values. The surface temperature of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous mask was 69.2 ℃ without a resistor connected in series. As the resistance gradually increased from 1 Ω to 5 Ω, the surface temperature of the face mask decreased correspondingly. When the resistance of the resistor was 5 Ω, the surface temperature of the face mask was 21.5 ℃. According to actual needs, the user can control the heating temperature of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous mask within a specific range by connecting a resistor with different resistance values. Fig. 8f provides the infrared thermal images of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous mask connected to different resistors. The surface temperature data in Fig. 8e was calculated by the infrared thermal imaging of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks. The recent reports on the preparation strategy and performance comparison of functional masks were shown in Table S2.

3. Conclusion

In this work, we designed a new face mask with excellent comfort and anti-pathogen functions to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic. Its core layer was composed of F-CNFs/CF nanofiber membranes. Compared to traditional surgical masks, the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous mask exhibited better heat dissipation efficiency. The F-CNFs/CF nanofibers membranes with a high conductivity converted electrical energy into heat to form a high-temperature layer. When connected to mobile power for 1 min, the surface temperature of the F-CNFs/CF nanocomposite fibrous masks reached 69.2 ℃. This formed a high-temperature layer that denatured the secondary structure of proteins in SARS-CoV-2, ultimately killing the virus. Additionally, the high-temperature layer also significantly inhibited bacteria, and the antibacterial rates reached 97.9% and 98.6% against E. coli and S. aureus when connected to a mobile power source for 30 min.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51473097), the Sichuan Science and Technology Project (2019YJ0107), and the Opening Project of State Key Laboratory of Polymer Materials Engineering (Sichuan University) (sklpme2014-3-14).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.134160.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Shen L., Wang C., Zhao J., Tang X., Shen Y., Lu M., Ding Z., Huang C., Zhang J., Li S., Lan J., Wong G., Zhu Y. Delayed specific IgM antibody responses observed among COVID-19 patients with severe progression. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):1096–1101. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1766382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang D., Choi H., Kim J.H., Choi J. Spatial epidemic dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;94:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waris A., Atta U.K., Ali M., Asmat A., Baset A. COVID-19 outbreak: current scenario of Pakistan. New Microbes New Infect. 2020;35:100681. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ait Addi R., Benksim A., Amine M., Cherkaoui M. COVID-19 Outbreak and Perspective in Morocco. Electr. J. General Med. 2020;17(4) doi: 10.29333/ejgm/7857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y., Ren B., Peng X., Hu T., Li J., Gong T., Tang B., Xu X., Zhou X. Saliva is a non-negligible factor in the spread of COVID-19. Mol. Oral. Microbiol. 2020;35(4):141–145. doi: 10.1111/omi.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coronavirus COVID-19 Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/.

- 7.Chen W.-H., Strych U., Hotez P.J., Bottazzi M.E. The SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Pipeline: an Overview. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2020;7(2):61–64. doi: 10.1007/s40475-020-00201-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiong S.-W., Fu P.-G., Zou Q., Chen L.-y., Jiang M.-Y., Zhang P., Wang Z.-G., Cui L.-S., Guo H.u., Gai J.-G. Heat Conduction and Antibacterial Hexagonal Boron Nitride/Polypropylene Nanocomposite Fibrous Membranes for Face Masks with Long-Time Wearing Performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;13(1):196–206. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c17800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Q., Bao L., Mao H., Wang L., Xu K., Yang M., Li Y., Zhu L., Wang N., Lv Z., Gao H., Ge X., Kan B., Hu Y., Liu J., Cai F., Jiang D., Yin Y., Qin C., Li J., Gong X., Lou X., Shi W., Wu D., Zhang H., Zhu L., Deng W., Li Y., Lu J., Li C., Wang X., Yin W., Zhang Y., Qin C. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;369(6499):77–81. doi: 10.1126/science.abc1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung C.C., Lam T.H., Cheng K.K. Mass masking in the COVID-19 epidemic: people need guidance. The Lancet. 2020;395(10228):945. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30520-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Atab N., Qaiser N., Badghaish H., Shaikh S.F., Hussain M.M. Flexible Nanoporous Template for the Design and Development of Reusable Anti-COVID-19 Hydrophobic Face Masks. ACS Nano. 2020;14(6):7659–7665. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c03976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang A., Cai L., Zhang R., Wang J., Hsu P.-C., Wang H., Zhou G., Xu J., Cui Y.i. Thermal Management in Nanofiber-Based Face Mask. Nano Lett. 2017;17(6):3506–3510. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b00579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu Y., Xiong S., Huang H., Zhao L., Nie K., Chen S., Xu J., Yin X., Wang H., Wang L. Fabrication and application of poly (phenylene sulfide) ultrafine fiber. React. Funct. Polym. 2020;150 doi: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2020.104539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavoie J.H., Rojas O.J., Khan S.A., Shim E. Migration Effects of Fluorochemical Melt Additives for Alcohol Repellency in Polypropylene Nonwoven Materials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12(32):36787–36798. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c10144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N., Tamin A., Harcourt J.L., Thornburg N.J., Gerber S.I., Lloyd-Smith J.O., de Wit E., Munster V.J. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(16):1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roman M.P., Thoppey N.M., Gorga R.E., Bochinski J.R., Clarke L.I. Maximizing Spontaneous Jet Density and Nanofiber Quality in Unconfined Electrospinning: The Role of Interjet Interactions. Macromolecules. 2013;46(18):7352–7362. doi: 10.1021/ma4013253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramakrishna S., Jose R., Archana P.S., Nair A.S., Balamurugan R., Venugopal J., Teo W.E. Science and engineering of electrospun nanofibers for advances in clean energy, water filtration, and regenerative medicine. J. Mater. Sci. 2010;45(23):6283–6312. doi: 10.1007/s10853-010-4509-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klemeš J.J., Fan Y.V., Tan R.R., Jiang P. Minimising the present and future plastic waste, energy and environmental footprints related to COVID-19. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020;127 doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2020.109883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Assiri A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Al-Rabeeah A.A., Al-Rabiah F.A., Al-Hajjar S., Al-Barrak A., Flemban H., Al-Nassir W.N., Balkhy H.H., Al-Hakeem R.F., Makhdoom H.Q., Zumla A.I., Memish Z.A. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2013;13(9):752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patrício Silva A.L., Prata J.C., Walker T.R., Duarte A.C., Ouyang W., Barcelò D., Rocha-Santos T. Increased plastic pollution due to COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and recommendations. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;405:126683. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.126683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zambrano-Monserrate M.A., Ruano M.A., Sanchez-Alcalde L. Indirect effects of COVID-19 on the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138813. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rather R.A. Demystifying the effects of perceived risk and fear on customer engagement, co-creation and revisit intention during COVID-19: A protection motivation theory approach. J. Destination Market. Manage. 2021;20 doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maher O.A., Kamal S.A., Newir A., Persson K.M. Utilization of greenhouse effect for the treatment of COVID-19 contaminated disposable waste - A simple technology for developing countries. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2021;232 doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2021.113690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong H., Zhu Z., Lin J., Cheung C.F., Lu V.L., Yan F., Chan C.-Y., Li G. Reusable and Recyclable Graphene Masks with Outstanding Superhydrophobic and Photothermal Performances. ACS Nano. 2020;14(5):6213–6221. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c02250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Q., Yin Y., Cao D., Wang Y., Luan P., Sun X., Liang W., Zhu H. Photocatalytic Rejuvenation Enabled Self-Sanitizing, Reusable, and Biodegradable Masks against COVID-19. ACS Nano. 2021;15(7):11992–12005. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c03249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Sio L., Ding B., Focsan M., Kogermann K., Pascoal‐Faria P., Petronela F., Mitchell G., Zussman E., Pierini F. Personalized Reusable Face Masks with Smart Nano‐Assisted Destruction of Pathogens for COVID‐19: A Visionary Road. Chem. Eur. J. 2021;27(20):6112–6130. doi: 10.1002/chem.202004875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karmacharya M., Kumar S., Gulenko O., Cho Y.-K. Advances in Facemasks during the COVID-19 Pandemic Era. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021;4(5):3891–3908. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.0c01329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melayil K.R., Mitra S.K. Wetting, Adhesion, and Droplet Impact on Face Masks. Langmuir. 2021;37(8):2810–2815. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c03556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng H., Alemany L.B., Margrave J.L., Khabashesku V.N. Sidewall Carboxylic Acid Functionalization of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125(49):15174–15182. doi: 10.1021/ja037746s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stobinski L., Lesiak B., Kövér L., Tóth J., Biniak S., Trykowski G., Judek J. Multiwall carbon nanotubes purification and oxidation by nitric acid studied by the FTIR and electron spectroscopy methods. J. Alloy. Compd. 2010;501(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2010.04.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu M., Cui Z., Ge F., Tian H., Wang X. Simple spray deposition of a hot water-repellent and oil-water separating superhydrophobic organic-inorganic hybrid coatings via methylsiloxane modification of hydrophilic nano-alumina. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018;125:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2018.08.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiong S.-W., Zhang P., Xia Y., Fu P.-G., Gai J.-G. Antimicrobial hexagonal boron nitride nanoplatelet composites for the thermal management of medical electronic devices. Mater. Chem. Front. 2019;3(11):2455–2462. doi: 10.1039/C9QM00411D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhi M., Manivannan A., Meng F., Wu N. Highly conductive electrospun carbon nanofiber/MnO2 coaxial nano-cables for high energy and power density supercapacitors. J. Power Sources. 2012;208:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2012.02.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma H., Zeng J., Realff M.L., Kumar S., Schiraldi D.A. Processing, structure, and properties of fibers from polyester/carbon nanofiber composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2003;63(11):1617–1628. doi: 10.1016/S0266-3538(03)00071-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He P., Gao Y., Lian J., Wang L., Qian D., Zhao J., Wang W., Schulz M.J., Zhou X.P., Shi D. Surface modification and ultrasonication effect on the mechanical properties of carbon nanofiber/polycarbonate composites. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2006;37(9):1270–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2005.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng Y., Zhao W., Jia D., Cui L., Liu J. Thermally-treated and acid-etched carbon fiber cloth based on pre-oxidized polyacrylonitrile as self-standing and high area-capacitance electrodes for flexible supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;364:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2019.01.076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yi Z., Cao Y., Yuan J., Mary C., Wan Z., Li Y., Zhu C., Zhang L., Zhu S. Functionalized carbon fibers assembly with Al/Bi2O3: A new strategy for high-reliability ignition. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;389:124254. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.124254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma J., Shang T., Ren L., Yao Y., Zhang T., Xie J., Zhang B., Zeng X., Sun R., Xu J.-B., Wong C.-P. Through-plane assembly of carbon fibers into 3D skeleton achieving enhanced thermal conductivity of a thermal interface material. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;380:122550. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2019.122550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morais D.S., Ávila B., Lopes C., Rodrigues M.A., Vaz F., Machado A.V., Fernandes M.H., Guedes R.M., Lopes M.A. Surface functionalization of polypropylene (PP) by chitosan immobilization to enhance human fibroblasts viability. Polym. Test. 2020;86:106507. doi: 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2020.106507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yim J.H., Rodriguez-Santiago V., Williams A.A., Gougousi T., Pappas D.D., Hirvonen J.K. Atmospheric pressure plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition of hydrophobic coatings using fluorine-based liquid precursors. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013;234:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2013.03.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dillon E.P., Crouse C.A., Barron A.R. Synthesis, Characterization, and Carbon Dioxide Adsorption of Covalently Attached Polyethyleneimine-Functionalized Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes. ACS Nano. 2008;2(1):156–164. doi: 10.1021/nn7002713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee S., Cho A.R., Park D., Kim J.K., Han K.S., Yoon I.-J., Lee M.H., Nah J. Reusable Polybenzimidazole Nanofiber Membrane Filter for Highly Breathable PM 2.5 Dust Proof Mask. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11(3):2750–2757. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b19741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Q. Zhang, Q. Zhao, Inactivating porcine coronavirus before nuclei acid isolation with the temperature higher than 56 °C damages its genome integrity seriously, bioRxiv (2020) 2020.02.20.958785. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.20.958785.

- 44.K. Shen, Y. Yang, T. Wang, D. Zhao, Y. Jiang, R. Jin, Y. Zheng, B. Xu, Z. Xie, L. Lin, Y. Shang, X. Lu, S. Shu, Y. Bai, J. Deng, M. Lu, L. Ye, X. Wang, Y. Wang, L. Gao, D. China National Clinical Research Center for Respiratory, B.C. National Center for Children’s Health, C.P.S.C.M.A. Group of Respirology, P. Chinese Medical Doctor Association Committee on Respirology, P. China Medicine Education Association Committee on, P. Chinese Research Hospital Association Committee on, P. Chinese Non-government Medical Institutions Association Committee on, C.o.C.s.H. China Association of Traditional Chinese Medicine, R. Medicine, C.o.C.s.S.M. China News of Drug Information Association, A. Global Pediatric Pulmonology, Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in children: experts’ consensus statement, World J. Pediatr. 16(3) (2020) 223-231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-020-00343-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Chin A.W.H., Chu J.T.S., Perera M.R.A., Hui K.P.Y., Yen H.-L., Chan M.C.W., Peiris M., Poon L.L.M. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. The Lancet Microbe. 2020;1(1) doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abraham J.P., Plourde B.D., Cheng L. Using heat to kill SARS-CoV-2. Rev. Med. Virol. 2020;30(5) doi: 10.1002/rmv.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shan X., Zhang H., Liu C., Yu L., Di Y., Zhang X., Dong L., Gan Z. Reusable Self-Sterilization Masks Based on Electrothermal Graphene Filters. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12(50):56579–56586. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c16754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shin B., Mondal S., Lee M., Kim S., Huh Y.-I., Nah C. Flexible thermoplastic polyurethane-carbon nanotube composites for electromagnetic interference shielding and thermal management. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;418 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.129282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song Q., Zhao R., Liu T., Gao L., Su C., Ye Y., Chan S.Y., Liu X., Wang K., Li P., Huang W. One-step vapor deposition of fluorinated polycationic coating to fabricate antifouling and anti-infective textile against drug-resistant bacteria and viruses. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;418 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.129368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.