Abstract

Colonization of the squid Euprymna scolopes by the bacterium Vibrio fischeri depends on bacterial biofilm formation, motility, and bioluminescence. Previous work has demonstrated an inhibitory role for the small RNA (sRNA) Qrr1 in quorum-induced bioluminescence of V. fischeri, but the contribution of the corresponding sRNA chaperone, Hfq, was not examined. We thus hypothesized V. fischeri Hfq similarly functions to inhibit bacterial bioluminescence as well as regulate other key steps of symbiosis, including bacterial biofilm formation and motility. Surprisingly, deletion of hfq increased luminescence of V. fischeri beyond what was observed for the loss of qrr1 sRNA. Epistasis experiments revealed that, while Hfq contributes to the Qrr1-dependent regulation of light production, it also functions independently of Qrr1 and its downstream target, LitR. This Hfq-dependent, Qrr1-independent regulation of bioluminescence is also independent of the major repressor of light production in V. fischeri, ArcA. We further determined that Hfq is required for full motility of V. fischeri in a mechanism that partially depends on the Qrr1/LitR regulators. Finally, Hfq also appears to function in the control of biofilm formation: loss of Hfq delayed the timing and diminished the extent of wrinkled colony development, but did not eliminate the production of SYP-polysaccharide-dependent cohesive colonies. Furthermore, loss of Hfq enhanced production of cellulose and resulted in increased Congo red binding. Together, these findings point to Hfq as an important regulator of multiple phenotypes relevant to symbiosis between V. fischeri and its squid host.

Keywords: Hfq, Vibrio fischeri, bioluminescence, Qrr1, biofilm, motility

1. INTRODUCTION

The marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri exclusively colonizes the light organ of Euprymna scolopes, the Hawaiian bobtail squid (reviewed in (1–4)). To establish a successful symbiosis with its host, V. fischeri needs to: 1) form an aggregate (a biofilm) on the surface of the symbiotic light organ; 2) disperse from the aggregate; 3) use chemotaxis and flagellar motility to enter the light organ and migrate into deep crypt spaces; 4) survive the physical and chemical aspects of the passage to the deep crypts; and 5) grow to high density and produce light in response to a quorum. Each aspect of this colonization process has been investigated and key regulatory and/or structural factors identified for each (reviewed in (5)). These include the cues that V. fischeri monitors, i.e., chitin and other nutrients, nitric oxide (NO), and autoinducer concentrations, and to which it responds appropriately by modulating flagella function, exopolysaccharide synthesis, and light production (6, 7).

The Hfq protein has been identified in many bacterial species as a chaperone of small non-coding RNAs (sRNAs) that post-transcriptionally control target mRNAs (8, 9). The majority of sRNAs are 50–200 nucleotides long and have limited and imperfect complementarity with either the 5’ or 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of the mRNA they control (10). Negative regulation of a target by sRNA occurs either by promoting degradation of the transcript through recruitment of RNAse or blocking access of the ribosomes to the initiation site (11–13). Alternatively, sRNAs can activate translation by facilitating access of the ribosomes through removal of the secondary structures that may sequester the ribosome-binding site. Hfq-dependent sRNAs rely on Hfq for their stability (and some for their expression) and typically act in trans on the target mRNAs. The chaperone binds to the AU-rich sequences of the mRNAs that it controls. A variety of genetic, biochemical and computational approaches have recently been employed to identify Hfq-associated sRNAs, as well as the large number of target mRNAs that they regulate (14–16). Delineating the physiological role of the sRNA interactions with their targets and the contribution of Hfq to particular phenotypes have been more challenging. There is a need to dissect the pathways of post-transcriptional control of gene expression via these regulators to achieve a more comprehensive picture of the layers of regulation required by bacteria under numerous conditions.

By facilitating base-pairing interactions of sRNAs with mRNAs, Hfq has been previously reported to regulate biofilm formation, virulence and many other phenotypes (17–21). However, it appears that the role of Hfq is species specific and the inactivation of Hfq has resulted in a range of effects in different species. hfq deletion strains have exhibited impaired growth, difficulties in coping with environmental stresses, changes in susceptibility to antibiotics, and for organisms that are pathogens, decreased virulence (18, 19).

One characterized example of an sRNA with a role in regulation of the V. fischeri-squid symbiosis is Qrr1 (22). This homolog of Qrr1–4 from V. cholerae and V. harveyi (20, 23–25) post-transcriptionally represses LitR, a master regulator of the bioluminescence operon (lux) (26) (Fig. 1). Despite the reported function of Qrr1 in controlling luminescence, the exact contribution of the sRNA chaperone Hfq to this regulation and other aspects of the physiology of V. fischeri has not been examined. Given the importance of Hfq in other bacteria, we hypothesized that Hfq could supply additional (post-transcriptional) control over key steps of symbiosis between the marine bacterium and its squid host, including bioluminescence, motility, and biofilm formation (Fig. 1). Here, we find that Hfq not only plays a key role in each of these processes but also that it functions via both Qrr1-dependent and -independent mechanisms, indicating the contribution of an as-yet unknown sRNA regulator in well-described processes such as bioluminescence.

Figure 1. A. Model for the role of Hfq in pathways important for host colonization by V. fischeri.

Work presented here shows that Hfq works via both Qrr1-dependent (blue arrows) and - independent (purple arrows) mechanisms; a role for Qrr1 in controlling biofilm formation is unclear. B. Regulation of bioluminescence in V. fischeri. At low cell density (left panel) expression of sRNA Qrr1 is induced by the quorum sensing regulator LuxO (not shown). In turn, Qrr1 represses LitR at a post-transcriptional level, resulting in little to no light production. Independent of quorum sensing, luminescence is negatively regulated by transcriptional repressor ArcA. When V. fischeri cells reach quorum (right panel), the repression of litR expression is relieved due to a decrease in qrr1 expression. At high cell density, LitR acts as the major positive regulator of bioluminescence by activating transcription of luxR, which encodes the direct transcriptional activator of the lux operon. The positioning of the Hfq chaperone in this diagram was based on models of its role in related organisms and has been supported by the genetic analyses in this work.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Strains and media.

Bacterial strains used and generated in this study are listed in Table 1. V. fischeri strain ES114 (70) was used as a genetic background for all further genetic manipulations. For routine culturing of V. fischeri strains, Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with sodium chloride and Tris (pH 7.5) (LBS) (71) was used. Other media were used for phenotype analysis as described below. E. coli strains were cultured on LB (72) medium at 37°C and supplemented with antibiotics and thymidine when needed. Antibiotics were added as appropriate at the following final concentrations: For V. fischeri: Chloramphenicol (Cm) (1 μg ml−1 for single copy selection or 5 μg ml−1 for plasmid maintenance), Erythromycin (5 μg ml−1), Kanamycin (Kan) (100 μg ml−1). For E. coli: Ampicillin (100 μg ml−1), Chloramphenicol (Cm) (12.5 μg ml−1), Kanamycin (Kan) (50 μg ml−1).

Table 1.

V. fischeri strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Derivation1 | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMJ2 | ΔarcA | N/A | (38) |

| ES114 | Wild Type | N/A | (70) |

| JB19 | litR::erm | N/A | (38) |

| JB21 | ΔarcA litR::erm | N/A | (38) |

| KV7860 | ΔbinK | N/A | (48) |

| KV7908 | ΔbcsA ΔbinK | N/A | (48) |

| KV8408 | bcsA::Tn5 | N/A | (61) |

| KV8563 | Δqrr1 Δhfq::FRT-erm | NT pLostfoX-Kan/TIM305 with pDNA, primers 2416 & 2417 (ES114), 2089 & 2090 (pKV494), and 2418 & 2419 (ES114) | This study |

| KV8573 | IG (yeiR-glmS)::ErmR-trunc TrimR Δhfq::FRT-Cm |

NT pLostfoX-Kan/KV8232 (61) with pDNA, primers 2416 & 2417 (ES114), 2089 & 2090 (pKV495), and 2418 & 2419 (ES114) | This study |

| KV8576 | ΔarcA Δhfq::FRT-Erm | NT pLostfoX-Kan/AMJ2 with pDNA, primers 2416 & 2417 (ES114), 2089 & 2090 (pKV494), and 2418 & 2419 (ES114) | This study |

| KV8577 | ΔarcA Δqrr1::FRT-Erm | NT pLostfoX-Kan/AMJ2 with pDNA, primers 2424 & 2425 (ES114), 2089 & 2090 (pKV494), and 2426 & 2427 (ES114) | This study |

| KV9050 | Δhfq::FRT-Cm | NT pLostfoX-Kan/ES114 with gKV8573 | This study |

| KV9069 | ΔbinK Δhfq::FRT-Cm | Transformation pLostfoX-Kan/KV7860 with gKV8573 | This study |

| KV9072 | Δhfq::FRT-Cm IG (yeiR-FRTerm/glmS)::hfq+ | NT pLostfoX-Kan/KV9050 with pDNA, primers 2290 & 2090 (pKV502), 2420 & 2421 (ES114) & 2196 & 1487 (pKV503) | This study |

| KV9075 | ΔbinK Δhfq::FRT-Cm IG (yeiR-FRTerm/glmS)::hfq+ | NT pLostfoX-Kan/KV9069 using DNA, primers 2290 & 2090 (pKV502), 2420 & 2421 (ES114) & 2196 & 1487 (pKV503) |

This study |

| KV9347 | Δqrr1 ΔbinK::FRT-Trim | NT plostfoX/TIM305 with gKV8458 (6) | This study |

| KV9444 | ΔbinK litR::erm | NT pLostfoX-Kan/KV7860 with gJB19 | This study |

| KV9445 | ΔbcsA ΔbinK Δhfq::FRT-Cm | NT pLostfoX-Kan/KV7908 with gKV9050 | This study |

| TIM305 | Δqrr1 | N/A | (22) |

| VAW43 | Δqrr1 litR::erm | NT pLostfoX-Kan/TIM305 with gJB19 | This study |

| VAW68 | ΔarcA Δhfq::FRT-Cm litR::erm | NT pLostfoX-Kan/KV8576 with gJB19 | This study |

| VAW73 | IG (yeiR-glmS)::ErmR-trunc TrimR Δhfq::FRT-Cm litR::erm | NT pLostfoX-Kan/KV8573 with gJB19 | This study |

| VAW74 | ΔarcA Δhfq ΔlitR::erm | This study | |

| VAW75 | Δqrr1 Δhfq ΔlitR::erm | This study |

NT, natural transformation; pDNA, DNA derived from PCR SOE reactions; g, genomic DNA of the indicated strain

2.2. Growth curves.

Strains of V. fischeri were cultured overnight in LBS or TMM (Tris Minimal Medium, which contains 300 mM sodium chloride, 50 mM magnesium sulfate, 0.33 mM potassium phosphate dibasic, 10 μM ferrous ammonium sulfate, 0.1% ammonium chloride, 10 mM N-acetylglucosamine, 10 mM potassium chloride, 10 mM calcium chloride, and 100 mM Tris pH 7.5) at 28°C for 14 hours. The cultures were then diluted to OD600 of 0.1 in 30 ml of LBS medium or to OD600 of 0.05 in 30 ml of TMM medium in 250 ml baffled flasks and incubated at 28°C or 24°C with 220 rpm of consistent shaking. Aliquots were withdrawn every hour for ten hours and the optical density were measured with BioMate 3 Thermo Spectronic. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.3. Strain construction/complementation.

Mutant strains were generated by transformation using a previously described procedure (73) with either genomic DNA (gDNA) from a marked mutant or PCR products generated via a PCR SOE approach (61). For the latter approach, sequences of about 500 bp from regions up- and downstream of the gene of interest were fused on either side of an antibiotic resistance cassette. Strains in which the composite fragment had recombined into the chromosome were selected using the appropriate antibiotic, and evaluated to confirm that gene replacement had occurred by PCR using the external primers. In some cases, intermediate strains were used as the initial recipient of the PCR DNA; from these strains, gDNA was collected and used to transform the appropriate final recipient.

2.4. Motility assay.

Bacteria were cultured overnight at 28°C in tryptone broth with added sodium chloride (TBS; contains 1% tryptone and 2% sodium chloride) (74). After ~2 h subculture in the same medium, the bacteria were standardized to an equal optical density at 600 nm (OD600) between 0.2 and 0.3. Aliquots of 10 μl were spotted on TBS soft agar (0.25% agar) supplemented with 35 mM MgSO4 and incubated at 28°C. The outer diameter of swimming cultures was measured hourly for 6 h. In addition, photographs were taken at the indicated time.

Luminescence measurements.

V. fischeri was cultured overnight in SWT (Sea Water Tryptone; contains 70% artificial sea water, 0.5% tryptone, 0.3% yeast extract) medium at 28°C. The cultures were then diluted to OD600 of 0.005 in 30 ml of SWTO (70% artificial sea water, 0.5% tryptone, 0.3% yeast extract, 2% sodium chloride) medium in 250 ml baffled flasks and incubated with shaking at 24°C. Aliquots of 1 ml were withdrawn every hour and luminescence measured in Turner Biosystems Luminometer (Model TD-20/20) after aeration, followed by optical density (OD600) reading with the BioPhotometer. Specific luminescence was determined as relative luminescence divided by OD600. These values were plotted against the OD600 values to permit a comparison of luminescence levels at similar cell densities.

2.5. Wrinkled colony assay.

Cultures grown in LBS overnight at 28°C were sub-cultured 1:100 in LBS and incubated at 28°C for 1.5 h. Density was standardized to OD600 0.2 and 10 μl aliquots of culture were spotted on one-day old LBS agar plates with or without 10 mM CaCl₂. Wrinkling at 28°C was monitored at the indicated times. At the last time point, the spots were disrupted to assess stickiness. Images of wrinkled colonies were generated using Zeiss Stemi 2000-c microscope and Jenoptik Gryphax Subra camera.

2.6. Congo red assay.

For a liter of LBS agar, 40 mg congo red and 15 mg Coomassie blue were added to make LBS Congo Red agar plates two days prior to streaking. V. fischeri strains were streaked onto LBS agar plates and allowed to grow overnight. Heavy streaks were applied from the overnight plates onto LBS Congo Red agar plates. The streaks were transferred onto paper after incubation at 24°C for 24 h to permit better visualization of the colony color, as described in (48). To quantify the amount of red color produced by each strain, V. fischeri strains were grown overnight in LBS. The next day, the strains were subcultured 1:100. After 1.5 h of growth, all strains were normalized to an OD600 of 0.2 and spotted onto two-day old Congo red plates. Spots were transferred onto paper following incubation at 24°C for 24 h. Color produced by each strain, denoted as the area, was quantified from scanned images using ImageJ.

2.7. qRT-PCR analysis.

To isolate RNA for litR transcript analysis, cultures were grown in SWTO at 24°C and aliquots collected at designated time points. Samples were mixed with 2x volume of RNA Protect Bacteria Reagent (Qiagen) and pellets stored after 10 min centrifugation at 5,000xg. RNA was extracted using MasterPure RNA purification kit (Epicentre) and treated with DNase to remove any genomic DNA. cDNA synthesis was performed using iScript kit (Bio-Rad) followed by qPCR using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on the CFX9q Real-Time System instrument (Bio-Rad). Primers qlitR-F and qlitR-R were used to amplify litR (test) transcript. 5S rRNA-specific primers P2242 and P2243 were used to amplify the reference transcript. Fold change in litR mRNA levels was determined using ΔΔCt method (75).

2.8. Bioinformatic analysis.

Amino acid sequences of the Hfq protein from E. coli, V. fischeri, V. cholerae and V. harveyi were retrieved from the NCBI database. The NCBI accession numbers used are as follows: 332341332 (E. coli), 171902228 (V. fischeri), 229368777 (V. cholerae), 57822740 (V. harveyi). The alignment was performed using the multiple alignment (EMBL-EBI; (27, 76)). The phylogenetic tree of Hfq sequences was constructed using Phylogeny.fr (28).

2.9. Statistical analysis.

GraphPad Prism (version 8) was used for graphical representation of results. Means and standard deviations were determined using the embedded statistics tools.

3. RESULTS

3.1. V. fischeri encodes a putative Hfq protein.

The sequence of the putative Hfq protein from V. fischeri strain ES114 (encoded by VF_2323) was aligned with those from E. coli, V. harveyi and V. cholerae using the EMBOSS tool for multiple sequence alignment Clustal Omega (Fig. 2A) (27). The N-terminal sequence of each of the four proteins is well conserved while the C-termini of the Vibrio proteins lack 13 amino acids found in the E. coli Hfq protein. Of the 72 N-terminal amino acids in Vibrio Hfq protein sequences, 69 are identical to those of E. coli, while only 6% of the C-terminal residues have homology to the E. coli Hfq. The phylogenetic tree (28) (Fig. 2B) constructed using the Hfq sequences of the four species reflects the 93.3% identity between the V. fischeri and V. harveyi proteins and 91% identity between V. fischeri and V. cholerae. This high level of conservation between the members of the Vibrionaceae family is expected and has been reported previously (29). The V. fischeri protein is overall 68.3% identical to the E. coli sequence, indicating the lesser homology of the overall sequence between different gamma-proteobacteria, mostly due to the difference in length and content of the C-terminal tail. Given the conservation of the V. fischeri protein and our phenotypic characterization described below, we designate VF_2323 as hfq.

Figure 2. Comparison of Hfq sequences from E. coli, V. fischeri, V. harveyi and V. cholerae.

A. Protein sequence alignment using EMBOSS Clustal Omega (27). Asterisks indicate identical amino acid residues, dashes indicate absence of residues, single and double dots indicate amino acid substitutions. B. Phylogenetic tree of Hfq sequences was generated using Phylogeny.fr (28) and rooted with the E. coli Hfq sequence.

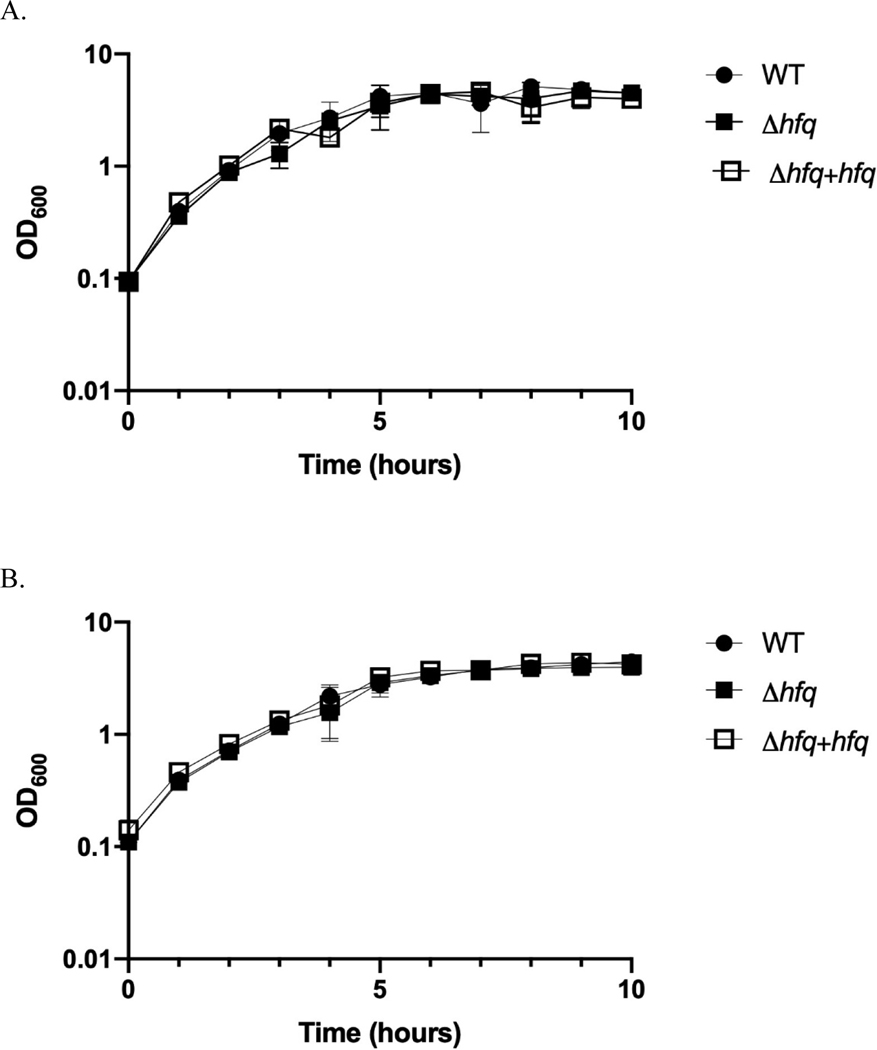

3.2. Hfq is required for growth of V. fischeri in minimal medium.

In other bacteria (including E. coli), Hfq controls a variety of traits including bacterial growth (30–34). To begin to understand the function of Hfq in V. fischeri, we generated hfq deletion and complementation strains. When grown at the optimal growth temperature of 28°C in a complex medium, these strains displayed no substantial differences in growth rates or final growth yields (Fig. 3A). Thus, loss of hfq does not affect growth of V. fischeri under these conditions. Similarly, when cultured in a complex medium at 24°C, there were no differences in growth of the three strains (Fig. 3B). In contrast, when grown in a minimal medium, the hfq mutant exhibited a severe defect in growth, especially at 24°C (Fig. 3C, D). Supplementing the medium with casamino acids restored growth to wild type levels (Fig. 3D). This suggests that Hfq serves as a pleiotropic regulator of gene expression in V. fischeri, required for optimal growth under nutrient-limiting conditions.

Figure 3. Deletion of hfq affects growth of V. fischeri in minimal, but not complex, medium.

Wild-type (WT) ES114 (black circles), Δhfq (KV9050, black squares) and complemented Δhfq + hfq (KV9072, open squares) strains were cultured in LBS medium at 28°C (A) and 24°C (B) and cell density measurements were taken hourly. The same strains were grown in TMM at 28°C (C) and 24°C (D). The Δhfq strain was also cultured in TMM at 24°C in the presence of 1% (up triangles) and 1.5% (down triangles) casamino acids (CAA) (D). All data are represented as means and standard deviation of triplicate biological replicates. Experiments were repeated on at least three independent occasions.

3.3. Hfq regulates luminescence in V. fischeri.

In other Vibrio species such as V. cholerae, Hfq functions in the quorum sensing pathway to negatively control production of the key regulator HapR at low cell density (19). In V. fischeri, Hfq is predicted to similarly control the HapR homolog LitR, which in turn controls luminescence (Fig. 1) (22). To test this prediction, we evaluated luminescence of the hfq mutant (Fig. 4). Consistent with the predicted negative regulatory function of Hfq, we found that the specific luminescence in the Δhfq strain, represented as relative luminescence per OD600, was increased 100-fold as compared to the wild-type strain, and this phenotype was complemented by restoring hfq to the mutant strain (Fig. 4). This altered light production was not due to a defect in growth, as growth of the hfq mutant was indistinguishable from that of the wild-type parent under the conditions used for this assay (Supp. Fig. 1).

Figure 4. Hfq is a repressor of bioluminescence.

Luminescence levels of the Wild-type (WT) (ES114, black circles), Δhfq mutant (KV9050, black squares), and complemented mutant Δhfq + hfq (KV9072, open squares) strains were monitored over time during growth in SWTO at 24°C. Relative light production (RLU) was averaged between duplicate measurements, normalized to cell density, and plotted against the optical density of the culture as described in the Materials and Methods section. The graph is a representative of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate and the error bars represent SD.

3.4. Hfq function overlaps with but is distinct from Qrr1 in controlling luminescence.

In V. harveyi, Hfq functions with any of five related sRNAs (Qrr1–5) to control LuxR production and quorum-dependent phenotypes, while in V. cholerae four Hfq-dependent sRNAs (Qrr1–4) regulate expression of transcription factor HapR (20, 23, 24). In contrast, V. fischeri contains only a single gene for Qrr, qrr1 (22). A qrr1 deletion mutant was previously reported to exhibit increased luminescence (22); however, only the maximal luminescence of the qrr1 mutant was reported (22), and no studies of hfq were included. Given that V. fischeri contains a single qrr1 gene, we predicted that the luminescence phenotypes of the hfq and qrr1 mutants would be the same. To test this prediction, we evaluated the relative luminescence levels of Δqrr1 and Δhfq mutants. As previously observed, the qrr1 mutant produced increased luminescence compared to the wild-type strain (22, 35) (Fig. 5). Unexpectedly, however, the Δhfq strain was ten-fold more luminescent than the qrr1 mutant at the peak of luminescence (Fig. 5). These data demonstrate that Hfq is indeed a repressor of luminescence in V. fischeri and suggest that Hfq has a function(s) in controlling luminescence that is independent of Qrr1.

Figure 5. Hfq and Qrr1 both repress luminescence, with Hfq having roles independent of Qrr1.

Bioluminescence assay measuring light production by the Wild-type (WT) (ES114, black circles) and strains lacking either hfq (KV8573, black squares), qrr1 (TIM305, up triangles) or both the chaperone and the sRNA (KV8563, open squares). A representative experiment done in triplicate is shown.

To further understand the relationship between Hfq, Qrr1 and control of luminescence, we generated a double hfq qrr1 mutant. This strain phenocopied the Δhfq single mutant with levels of luminescence that were ten-fold greater than the strain that only lacks Qrr1 (Fig. 5). These data reveal that Hfq is dominant to Qrr1 in the bioluminescence pathway and support the hypothesis that Hfq has a function independent of Qrr1.

3.5. Hfq functions independently of LitR to control luminescence.

Our data indicated that Hfq represses luminescence independently of Qrr1. Because Qrr1 targets LitR translation (22, 36), we hypothesized that Hfq could function with an additional sRNA to control LitR translation and thus luminescence. Alternatively, Hfq could control luminescence at a distinct point in the luminescence pathway (Fig. 1). To distinguish between these possibilities, we compared the luminescence phenotypes of single and double mutants of hfq, qrr1, and litR. As previously reported, the litR mutant produced low levels of luminescence, while the single hfq and qrr1 mutants exhibited increased luminescence as described above (Fig. 6) (36, 37). The double qrr1 litR mutant produced minimal amounts of light similar to the litR single mutant (Fig. 6) as expected given the direct role of Qrr1 in controlling LitR production (22). In contrast, however, the double hfq litR mutant achieved increased levels of light relative to the litR mutant, although diminished relative to the wild-type and hfq single mutant strains. These data confirm the conclusion that Hfq has a role independent of Qrr1 and indicate that this effect occurs at a level distinct from control of LitR.

Figure 6. Hfq and LitR independently control a converging target in the luminescence pathway.

Luminescence levels of the Wild-type (WT) (ES114, black circles), litR (JB19, black squares), Δqrr1 litR (VAW43, open squares) and Δhfq litR (VAW73, open circles) strains were monitored over time during growth in SWTO at 24°C. Relative light production (RLU) was measured in duplicate, normalized to cell density, and plotted against the optical density of the culture as described in the Materials and Methods section. The graph is a representative of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate and the error bars represent SD.

To assess whether Hfq cooperates with Qrr1 in controlling levels of LitR, we measured litR transcript levels in strains lacking hfq and qrr1. As previously reported (22), the levels of litR transcript were increased in Δqrr1 strain as compared to wild- type, but only at an early time point, two hours after subculture (Fig. 7). After this time point, the levels of litR mRNA returned to approximately wild-type levels. In the hfq mutant strain, litR expression was increased for at least an additional hour (Fig. 7) and then returned to the levels comparable to that of wild-type and the qrr1 mutant strain. The different litR mRNA levels in the two strains suggest that Hfq and Qrr1 may control litR in concert for a short period of time after which Hfq regulation may continue without Qrr1. This subtle distinction in regulation of litR by the chaperone and the sRNA is additional support that Hfq can contribute to bioluminescence control with room for additional targets.

Figure 7. Hfq effect on litR expression is distinct from the effect of Qrr1.

litR transcript levels in strains lacking either hfq (KV8573) or qrr1 (TIM305) were measured by quantitative RT-PCR and compared to the Wild-type (WT) (ES114) at different time points. Red dashed line represents the level of litR transcript in the WT V. fischeri. Error bars indicate SD of triplicate measurements. The graph is a representative of three independent experiments.

3.6. Hfq exerts its function independent of negative regulator ArcA.

Another major regulator of luminescence is the response regulator ArcA, which binds to the promoter region upstream of luxI to inhibit luminescence (Fig. 1B) (38–40). Thus, we considered the possibility that Hfq could inhibit light production independently of Qrr1 and LitR by controlling ArcA production or activity. If that were the case, then the quorum sensing-independent effect of Hfq on luminescence would depend on ArcA. To test this possibility, we examined light production of strains with single or multiple mutations (Fig. 8A). As reported previously, loss of the major repressor of luminescence ArcA led to increased light production (38), even at low cell density. This light phenotype was distinct from and higher than that of the Δhfq Δqrr1 mutant (Fig. 8A), suggesting that ArcA is more potent at repressing luminescence than Hfq. Loss of both ArcA and Qrr1 resulted in higher light production than the ArcA single mutant. This result is consistent with the fact that these regulators exert effects at different points in the luminescence pathway (Fig. 1B). When both arcA and hfq were deleted, the resulting strain produced levels of light that were higher not only than the arcA single mutant but also the arcA qrr1 double mutant; the difference between these two double mutants is similar to that seen for the single hfq and qrr1 mutants (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, a triple mutant lacking all three negative regulators exhibited levels of light indistinguishable from the arcA hfq double mutant. These data suggest that Hfq exerts its function independently of ArcA activity.

Figure 8. Epistatic analysis of the role of Hfq, Qrr1, LitR and ArcA in controlling V. fischeri bioluminescence.

A. Hfq and Qrr1 augment the repression of luminescence by ArcA. Luminescence levels of the Wild-type (WT) (ES114, black circles), ΔarcA (AMJ2, open circles) ΔarcA Δhfq (KV8576, black squares), ΔarcA Δqrr1 (KV8577, open squares), Δhfq Δqrr1 (KV8563, down triangles) and ΔarcA Δhfq Δqrr1 (VAW68, up triangles) strains were monitored over time during growth in SWTO at 24 °C. Relative light production (RLU) was measured in duplicate, normalized to cell density, and plotted against the optical density of the culture as described in the Materials and Methods section. B. Hfq controls luminescence through a LitR- and ArcA-independent mechanism(s). Luminescence levels of the Wild-type (WT) (ES114, black circles), ΔarcA Δhfq (KV8576, black squares), ΔarcA litR (JB21, triangles), ΔarcA Δhfq litR (VAW74, open squares) and Δhfq litR (VAW73, open circles) strains were monitored as above. Each of the graphs is a representative of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate and the error bars represent SD.

Because the three regulators exert effects in the same direction, we performed one more set of epistasis experiments to solidify our understanding of the role of Hfq relative to the other regulators. Specifically, because Qrr1 functions upstream of LitR, and because disruption of litR exerts the opposite phenotype (decreased rather than increased luminescence), we assessed the luminescence properties of the arcA hfq litR triple mutant relative to the double mutants. Similar to what we observed for the arcA hfq qrr1 triple (Fig. 8A) the arcA hfq litR triple exhibited increased luminescence relative to the arcA litR double mutant (as well as the hfq litR mutant), but less than the arcA hfq double (Fig. 8B). Together, these data indicate Hfq functions to control luminescence through both a Qrr1- and LitR-dependent mechanism and a mechanism that is independent of those regulators and ArcA.

3.7. Hfq function overlaps with but is distinct from Qrr1 in controlling motility.

LitR is known to control V. fischeri motility (26). Thus, we wondered if Hfq would also control motility, and if so, if that control occurs exclusively via the effect of Hfq on the pathway that involves the quorum sensing regulators Qrr1 and LitR. To test this possibility, we first examined the effect of the loss of Hfq on motility of V. fischeri in a soft agar medium. Motility was decreased in the Δhfq strain compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 9). This defect was restored by complementation with hfq. Thus, Hfq is a positive regulator of motility in V. fischeri.

Figure 9. Loss of Hfq reduces V. fischeri motility.

A. Migration of the Wild-type (WT) (ES114, black circles), Δhfq mutant (KV9050, black squares), and complemented mutant Δhfq + hfq (KV9072, open squares) strains was measured in TBS+Mg2+ agar (0.25%) over 5.5 hours at 28°C. A representative experiment done in triplicate is shown. Error bars correspond to SD. B. Representative image of a motility agar plate at the 5.5 h time point.

Given that Hfq functions both with and independently of Qrr1 to control luminescence, we wondered if the role of Hfq in controlling motility was dependent on or independent of Qrr1. We thus evaluated motility of strains that lacked either the chaperone or the sRNA or both. We observed a modest defect in motility for a qrr1 single mutant, as has been reported previously (Fig. 10A). The single hfq mutant had a more severe motility defect than the qrr1 mutant. Finally, the double mutant phenocopied the hfq mutant. Together, these data suggest that control of motility by Hfq is distinct from control by Qrr1.

Figure 10. Hfq promotes motility through a mechanism that is partially independent of LitR.

A. Migration was examined in Wild-type (WT) (ES114, black circles), Δhfq (KV8573, black squares), Δqrr1 (TIM305, triangles) and Δhfq Δqrr1 (KV8563, open squares) strains as described in the legend to Figure 8. A representative experiment done in triplicate is shown. Error bars correspond to SD. B. Strain lacking a repressor of motility (LitR) and either Hfq, Qrr1, or both were examined for motility. Wild-type (WT) (ES114, red circles), Δhfq (KV8573, black squares), litR (JB19, green triangles), Δqrr1 litR (VAW43, open circles), Δhfq litR (VAW73, open squares), and Δhfq Δqrr1 litR (VAW75, open blue triangles). A representative experiment done in triplicate is shown. Error bars correspond to SD.

Because both mutations caused decreased motility, however, it was not possible to fully assess the epistatic relationship between these regulators. To ask this question, we evaluated mutants that also lacked LitR. Although disruption of litR has been reported to increase motility (41), under our conditions, the litR mutant exhibited motility that was similar to the wild-type parent (Fig. 10B). The double litR qrr1 mutant strain also phenocopied the wild-type strain. This result indicates that the litR mutation suppressed the motility defect of the qrr1 mutant, supporting previous findings of increased motility for a litR mutant. In contrast, while the litR hfq mutant also had greater motility relative to the hfq mutant, it was not equivalent to the wild-type strain. Finally, the litR hfq qrr1 triple mutant phenocopied the litR hfq double mutant. These data support the conclusion that Hfq stimulates motility through both Qrr1-dependent (LitR-dependent) and –independent mechanisms. Whether the Qrr1-independent control of motility by Hfq relies on the same downstream target/process as does the control of luminescence remains to be determined.

3.8. Hfq is required for timely biofilm formation in V. fischeri.

Hfq has been found to control biofilm formation in other bacteria (21, 42, 43), which prompted us to ask if Hfq plays a similar role in V. fischeri. To answer this question, we used the wrinkled colony assay with a parent strain that lacks the negative regulator of biofilms, BinK (44). While the parent strain started to form a biofilm at 24 hours, as evidenced by visible colony architecture, the Δhfq strain exhibited substantial, ~2-day delay in this process (Fig. 11A). Even at the last time point (72 hours), the architecture of the wrinkled colony formed by the hfq mutant was distinct from its parent, i.e. less wrinkling by the mutant. However, at the final time point, the colony displayed a cohesiveness similar to that of its parent, indicating that SYP, the major polysaccharide responsible for colony cohesiveness (45), was sufficiently produced. The complemented hfq mutant was restored to the parental timing and pattern. This suggests that Hfq positively regulates biofilm formation in V. fischeri.

Figure 11. Role of Hfq in biofilm formation of V. fischeri.

The wrinkled colony assay was performed by spotting cultures of various strains on LBS with (A) or without (B) 10 mM calcium chloride, and incubating them at 24°C. The strains pictured are (A) ΔbinK (KV7860), ΔbinK Δqrr1 (KV9347), ΔbinK litR (KV9444), ΔbinK Δhfq (KV9069), and ΔbinK Δhfq hfq+ (KV9075) for the calcium condition and (B) ΔbinK (KV7860), ΔbinK Δhfq (KV9069), ΔbinK Δhfq hfq+ (KV9075), and ΔbinK Δhfq ΔbcsA (KV9445) in the no calcium condition. Spots were visualized at the indicated time points using the Zeiss Stemi 2000-c microscope and a Jenoptik Gryphax Subra camera. “Disrupt” refers to the disruption of the spots using a toothpick at 72 h.

In the related microbe Aliivibrio salmonicida, LitR is a negative regulator of biofilm formation (46, 47). To date, no role in biofilm formation in V. fischeri has been reported for this regulator or for Qrr1. Because we found that Hfq acts both in concert with LitR and Qrr1 and in pathways independent of these regulators when controlling bioluminescence and motility, we explored whether Hfq regulates biofilm formation with the involvement of LitR and Qrr1. Under our conditions, which includes calcium to induce biofilm formation (48), the Δqrr1 and litR strains show more, though subtle, wrinkling at earlier time points than the parent strain (compare time points 30 h, 36 h, and 48 h for the mutants vs. the parent ΔbinK strain) (Fig. 11A). This increased biofilm phenotype implicates LitR and Qrr1 as repressors of biofilm formation, with LitR exerting a greater effect. In contrast to the other LitR and Qrr1-controlled phenotypes, however, biofilm formation is impacted in the same direction by both the Δqrr1 and litR mutations, rather than in opposite directions as would be expected. Furthermore, neither mutation exerts an effect in the same direction as the hfq mutant, making it unlikely that Hfq functions via these regulators to control biofilm formation. Overall, these results demonstrate that Hfq plays a key and previously unknown role in promoting wrinkled colony formation independent of the function of LitR and Qrr1, while also revealing roles for the latter regulators as biofilm inhibitors.

3.9. Hfq inhibits cellulose production.

The data presented in Fig. 11A were generated in the presence of calcium, a necessary signal for biofilm formation by the binK mutant. In the absence of calcium, as expected, none of the strains formed cohesive wrinkled colonies (Fig. 11B and Supp. Fig. 2). However, we found that the Δhfq derivative exhibited some colony architecture not observed for the binK mutant parent: the colony was bumpy rather than smooth (Fig. 11B). The bumpy architecture did not correspond to cohesiveness, as evidenced by the easy disruption of the colony (last panel of the Fig. 11B). Thus, we hypothesized that the colony architecture was due to cellulose rather than to SYP (48).

To determine if Hfq contributes to the control of cellulose production, we assessed colony color on Congo red medium. In V. fischeri, cellulose is a product of the bcs locus and a strain that lacks the bcsA gene appears beige on Congo red medium. In contrast, the WT strain produces cellulose and thus appears red (Fig. 12A and C). Deletion of hfq resulted in a brighter red appearance of the streak on Congo red, which was restored to the level of the WT by complementation with hfq gene. Unlike deletion of hfq, which results in increased cellulose production as measured by this assay, loss of qrr1 and litR did not affect the amount of cellulose, as these strains appear comparable in color to the WT strain (Fig. 12A and C).

Figure 12. Congo red assay reveals cellulose regulation by Hfq in V. fischeri.

Strains were streaked onto LBS congo red plates to analyze their ability to bind Congo red, and indirect measure of cellulose production. After 24h at 24°C, the streaks were transferred to paper for better visualization. Wild-type-derived (A) and ΔbinK-derived strains (B) are shown as follows in a clockwise direction: (left): WT (wild-type strain ES114), Δhfq (KV9050), Δhfq hfq+ (KV9072), litR (KV6647), Δqrr1 (KV6678), and bcsA (KV8408). (right) WT (wild-type strain ES114), ΔbinK (KV7860), ΔbinK Δhfq (KV9069), ΔbinK Δhfq hfq+ (KV9075), and ΔbinK Δhfq ΔbcsA (KV9445), and ΔbinK ΔbcsA (KV7908). (Wild-type ES114 is included on both plates as an internal control.) (C) and (D) are quantifications of color produced by the same strains as shown in (A) and (B), respectively, but spotted onto plates rather than streaked, as shown in Supp. Fig. 3 and processed as described in Materials and Methods. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the means of area for different strains (ns, no significant difference; *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ****, p<0.001).

For a further verification that the Hfq-dependent colony architecture on medium lacking calcium (Fig. 11B) was due to the cellulose, we generated a triple binK hfq bcsA mutant and tested its behavior in (A) the Congo red assay and (B) colony architecture in the wrinkled colony assay. In the Congo red assay, the hfq and binK hfq mutants produced colonies with a brighter red hue relative to their respective WT and binK mutant parents. The colony color was restored to the parental color upon complementation (Fig. 12B and D). The triple binK hfq bcsA mutant appeared indistinguishable from the binK bcsA double mutant. This suggests that the Congo red phenotype of the binK hfq double mutant is due to the role of Hfq in controlling cellulose production. Correspondingly, when we evaluated colony architecture of these strains without calcium, unlike its binK hfq parent, the bcsA derivative exhibited smooth colony architecture similar to the binK single mutant (Fig. 11B), indicating that the bumpy colony architecture was dependent on cellulose production. Together, these data identify a novel phenotype for Hfq in controlling cellulose production.

4. DISCUSSION

As a global regulator, Hfq contributes to a range of key functions, such as bacterial response to stress, virulence of pathogens, and group behaviors (i.e., bioluminescence and biofilm formation), among others. While these contributions of Hfq have been examined in Gram-negative and Gram-positive model species, and include some commonalities as well as differences, the role of Hfq in regulating key functions of the marine bacterium V. fischeri has not been directly investigated. In this study, we contribute to the understanding of V. fischeri regulatory networks by identifying Hfq as a negative regulator of bioluminescence and a positive regulator of motility and biofilm formation. Specifically, we show that the chaperone acts along with- and independently of- known regulators of these processes, Qrr1 and LitR.

The regulatory role of Hfq in the bioluminescence pathway of V. fischeri has thus far only been presumed, based on the similarity of the function of the Qrr1 sRNA from V. fischeri to Qrr (and correspondingly Hfq) function in other Vibrios (20, 22, 23). Here, we confirm that Hfq acts as a repressor of bioluminescence in V. fischeri (Fig. 4 and Supp. Fig. 4) and also uncover a Qrr1-independent role for Hfq in the control of light production (Fig. 5). While Hfq may assist Qrr1 in repressing litR mRNA translation, the tenfold increase in luminescence of the Δhfq and Δhfq Δqrr1 strains relative to the Δqrr1 mutant suggested that additional sRNA(s) may be controlled by Hfq. It is not unprecedented for the Hfq chaperone to be used by multiple sRNAs in regulating a single pathway, including the regulation of LitR homologue HapR in other Vibrios (49–51), which may be the case for the control of bioluminescence in V. fischeri. In a recent report (52), an RNA-seq analysis identified six sRNAs in the V. fischeri outer membrane vesicles and also in the hemolymph of the squid host. Four of the six sRNAs examined have specific protein chaperones distinct from Hfq, and the remaining two were present in relatively small percentages. While this work did not specifically focus on the role of these sRNAs in luminescence it affirms our hypothesis that additional, yet to be identified, sRNAs partner with Hfq to control bioluminescence and ultimately symbiosis.

Moreover, our epistasis experiments demonstrated that an additional sRNA partner must have a target that is distinct from litR, the target of Qrr1. Given the increased luminescence phenotype of the hfq mutant and the known function of Hfq, we hypothesized that Hfq (and an unknown sRNA) either represses an activator of luminescence (similar to its effect on LitR) or activates a repressor. We tested one such possible target, the response regulator ArcA, an important bioluminescence repressor in V. fischeri. We expected that, if Hfq inhibits luminescence by activating the ArcA repressor, then there would be no additional consequence of deleting hfq in the context of an arcA or arcA litR double mutant. However, this was not the case, a result that indicated that Hfq does not exert its activity through ArcA. While these data confirmed that this sRNA chaperone works on an additional target to inhibit bioluminescence, positioning Hfq in two distinct locations in bioluminescence control (Fig. 1A), the identity of the additional target(s) remains to be determined. Additional regulators are known to control luminescence, acting outside of the established phosphorelay. For example, Hfq could inhibit the autoinducer synthase AinS, a positive regulator that produces C8-HSL autoinducer. C8-HSL works both via the phosphorelay to indirectly control LitR and by directly binding to and activating LuxR, the proximal luminescence regulator (35). Repression of AinS production (and thus C8-HSL synthesis) would lead to decreased luminescence that is independent of Qrr1-mediated repression of LitR. Alternatively, Hfq could inhibit the expression of cyclic-AMP receptor protein (CRP), which is a known regulator of lux (35) and also a known regulator of metabolism. A crp deletion mutant of V. fischeri exhibited a two-log decrease in luminescence compared to ES114 (53), which is the equivalent to the increase in luminescence caused by the loss of hfq (Fig. 5). It is thus formally possible that Hfq indirectly controls luminescence by regulating the availability of the bioluminescence substrate via control of CRP. Finally, Hfq may impact an as-yet unknown luminescence regulator. Further genetic and epistatic analysis will be necessary to identify the additional luminescence-relevant target(s) of Hfq in V. fischeri.

The contribution of Hfq to the regulation of motility has been appreciated for some time in E. coli and Salmonella enterica servovar Typhimurium; this is mostly based on the findings that Hfq-dependent sRNAs regulate expression of flagellar genes (54–56). We show that Hfq promotes motility in V. fischeri and that it does so in a manner that is partially independent of Qrr1 and LitR (Fig. 9 and 10). Previous work has found LitR to be a negative regulator of motility (41), although under our assay conditions the litR mutant did not show a significant difference in motility from the wild type strain as was reported by Fidopiastis et al. (26) and by Dial et al. (57); however, its role as a negative regulator was clear from our epistasis analyses. The regulation by Hfq in the motility pathway appears to be in the opposite direction from its role in controlling bioluminescence where Hfq acts as a repressor. As in the bioluminescence regulatory pathway, the contribution of Hfq appears to be greater than that of Qrr1 sRNA (Fig. 10), which suggests a role for an as yet un-identified sRNA (or multiple sRNAs) that operates under Hfq guidance. In bacterial species where regulation of flagellar-based motility has been examined at the post-transcriptional level, it has been determined to be dependent on multiple sRNAs (17, 54, 56). Thus, it will be of interest to determine if the Hfq-dependent sRNA (other than Qrr1) that functions in luminescence control is the same one involved in the regulation of motility in V. fischeri.

The number of sRNAs that require Hfq for proper target regulation in E. coli is on the order of several hundred (10, 14, 58). There are, for example, multiple sRNAs interacting with Hfq that affect motility (i.e. ArcZ, OmrA/B, OxyS, McaS, MicA) in E. coli (54), but the homologs of these are not easily identifiable in the genome of V. fischeri. In addition to Hfq, another sRNA chaperone, ProQ, has recently been determined to have both an overlapping and a distinct set of sRNAs with which it post-transcriptionally affects targets controlled by Hfq (49, 59, 60). Whether the same is true for V. fischeri remains unknown, although a putative proQ gene exists in the genome. A global analysis of sRNAs, their chaperones and mRNA targets would help illuminate the similarities and differences between V. fischeri and other Gram-negative bacteria for which this has already been determined.

Similar to what we found for the regulation of motility in V. fischeri, Hfq also positively regulates syp-dependent biofilm formation (Fig. 11). Specifically, Hfq plays a substantial role in promoting the development of wrinkled colonies, although sticky, SYP-dependent colonies can form in the absence of Hfq. This chaperone also negatively controls the cellulose component of the biofilm: in the absence of the biofilm-inducing signal calcium, the biofilm-competent parent strain fails to form a biofilm, while the Δhfq derivative produced colonies with architecture, but lacking stickiness. This phenotype is consistent with that of a cellulose-dependent biofilm (48, 61), and indeed, was disrupted when cellulose-production components were also eliminated (Fig. 11B). Furthermore, the Δhfq mutant exhibited a cellulose-dependent increase in binding to Congo Red relative to the wild-type strain (Fig. 12). This role for Hfq in controlling cellulose coincides with what has been reported for enteric pathogens where the expression of curli, extracellular proteinaceous structures (62, 63) and cellulose important for biofilm formation, have been found to be post-transcriptionally controlled by several sRNAs. In addition to ascribing a role for Hfq in control of cellulose-dependent biofilms, we have also uncovered a previously unknown contribution of LitR as a repressor of SYP-dependent biofilms in V. fischeri (Fig. 11A). While the opposite effects of Hfq and LitR on biofilms are not surprising, the same direction (i.e., repression) of regulation by LitR and Qrr1 is. Since Qrr1 is a repressor of LitR (Fig. 1B), we would expect that the phenotypes of the strains that lack these regulators would produce opposite phenotypes, but they both resulted in earlier and more robust biofilms than the parent strain (Fig. 11A). An explanation for this may be that additional regulators control the function of LitR in the biofilm pathway. Recently, a novel LitR regulator in V. fischeri, HbtR, a homolog of V. cholerae virulence factor TcpP, has been described (64). The contribution of this regulator to biofilm formation, however, remains to be investigated.

An examination of the protein sequence of V. fischeri Hfq and comparison with that of E. coli revealed a high level of identity, with the major difference being a shorter C-terminal region in V. fischeri (Fig 2A). Pseudomonas aeruginosa also encodes an Hfq that lacks the C-terminal amino acids found in E. coli, yet this protein was able to functionally replace the E. coli Hfq (65), indicating that the functional domain of Hfq resides in the N-terminus. The stretch of approximately 12 amino acids that is found in E. coli Hfq C-terminus (and absent from Hfq of the Vibrios) is thought to contribute to nucleic acid binding, but until recently its structure had remained elusive (66–68). A comparison of the Hfq proteins from E. coli and V. cholerae using biochemical and biophysical approaches has shown that, despite the similarity in structure and ability to bind to Qrr sRNA, there is a difference in the stability of the hexamers (29). It was proposed that this is due to the difference in the subunit interface and that the higher stability of the E. coli Hfq is mediated by the longer C-terminal domain (29). A new and unique role for the C-terminus of Hfq was proposed when it was found to interact with lipid bilayers and liposomes, suggesting that the chaperone may be involved in accompanying sRNAs outside of the cell (69). It would be of interest to determine whether Hfq of Vibrios could accomplish this task in the absence of the C-terminal tail, since it has been reported that outer membrane vesicles influence V. fischeri’s interaction with its symbiotic host (52).

In conclusion, we ascribe to Hfq roles in the regulation of growth, bioluminescence, motility, and biofilm formation in V. fischeri. Based on our epistatic analysis, we can place the chaperone in previously described pathways (Fig. 1), where its role had only been postulated, and in another unknown pathway(s) controlling these processes. Thus, our work contributes towards a greater understanding of the complexity of regulatory networks that integrate environmental cues and allow V. fischeri to establish a productive symbiosis with the squid host.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Plasmids used in this study

Table 3.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer | Purpose | Sequence1 |

|---|---|---|

| 2089 | Amplify AbR cassette, F | CCATACTTAGTGCGGCCGCCTA |

| 2090 | Amplify AbR cassette, R | CCATGGCCTTCTAGGCCTATCC |

| 2416 | Delete hfq, upstream | CGTTGGAAGTATTTCGAATTTCG |

| 2417 | Delete hfq, upstream | taggcggccgcactaagtatggGCTATGAGCCTTTAGCTTATGAC |

| 2418 | Delete hfq, downstream | ggataggcctagaaggccatggCTAGAATAGTTAATCAGTTAAGG |

| 2419 | Delete hfq, downstream | GCTTTAATACGTTCACGCAACAATCG |

| 2420 | Complement hfq | ggataggcctagaaggccatggGCTTCAATGTTGTTTAACTTAAGTGC |

| 2421 | Complement hfq | taggcggccgcactaagtatggCCTTAACTGATTAACTATTCTAG |

| 2290 | Amplify from middle of ErmR | AAGAAACCGATACCGTTTACG |

| 1487 | Amplify glmS | GGTCGTGGGGAGTTTTATCC |

| 2196 | Amplify glmS | tCCATACTTAGTGCGGCCGCCTA |

| 2424 | Delete qrr1, upstream | GGTATCTTTTGGATTCTCTTGG |

| 2425 | Delete qrr1, upstream | taggcggccgcactaagtatggCCTATTGCAGGGAGCGTGCCAAC |

| 2426 | Delete qrr1, downstream | ggataggcctagaaggccatggGCTATAAAATCAATAACTAACTATTC |

| 2427 | Delete qrr1, downstream | CGCTTAGGTGAGTTTGATGTCC |

| 2242 | 5S rRNA, qRT-PCR, F | TGATCCCATGCCGAACTCAGAAG |

| 2243 | 5S rRNA, qRT-PCR, R | CCTGGCGATGTCCTACTCTCAC |

| qlitR-F | litR, qRT-PCR, F | AAGGCCTAGAACAAGGCTATC |

| qlitR-R | litR, qRT-PCR, R | GACAGAGACCTGAGCGATTT |

Lowercase letters indicate “tail” sequences not complementary to the template.

Highlights.

sRNAs are key players in the post-transcriptional control of gene expression in bacteria.

Chaperone Hfq partners hundreds of sRNAs with target mRNAs in many Gram-negative bacteria.

In marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri Hfq has been implicated in the pairing of sRNA Qrr1 and target LitR, which regulate bioluminescence.

Hfq controls bioluminescence, motility and cellulose polysaccharide production in V. fischeri by Qrr1-dependent and -independent mechanisms..

ACKNOWLDEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Wheaton College Aldeen Grants (JT) and NIH General Medical Sciences grants R01 GM114288 and R35 GM130355 (KV). The authors thank previous members of Tepavcevic lab, current and present members of the Visick lab, and students in Biol252 course at Wheaton College for helpful discussion.

Glossary

- A

absorbance (1 cm)

- bp

base pair(s)

- cDNA

DNA complementary to RNA

- Δ

deletion

- nt

nucleotide(s)

- ORF

open reading frame

- RBS

ribosome binding site

- RLU

relative light units

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Norsworthy A, Visick K. 2013. Gimme shelter: how Vibrio fischeri successfully navigates an animal’s multiple environments. Front Microbiol 4:356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandel MJ, Dunn AK. 2016. Impact and Influence of the Natural Vibrio-Squid Symbiosis in Understanding Bacterial–Animal Interactions. Front Microbiol 7:1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Visick KL. 2009. An intricate network of regulators controls biofilm formation and colonization by Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 74:782–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma SC, Miyashiro T. 2013. Quorum Sensing in the Squid-Vibrio Symbiosis. Int J Mol Sci 14(8): 16386–16401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visick KL, Stabb EV, Ruby EG. 2021. A lasting symbiosis: how Vibrio fischeri finds a squid partner and persists within its natural host. Nat Rev Microbiol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Thompson CM, Tischler AH, Tarnowski DA, Mandel MJ, Visick KL. 2019. Nitric oxide inhibits biofilm formation by Vibrio fischeri via the nitric oxide sensor HnoX. Mol Microbiol 111:187–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Septer AN, Lyell NL, Stabb EV. 2013. The Iron-Dependent Regulator Fur Controls Pheromone Signaling Systems and Luminescence in the Squid Symbiont Vibrio fischeri ES114. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavita K, de Mets F, Gottesman S. 2018. New aspects of RNA-based regulation by Hfq and its partner sRNAs. Cell Regul 42:53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soper T, Mandin P, Majdalani N, Gottesman S, Woodson SA. 2010. Positive regulation by small RNAs and the role of Hfq. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107:9602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottesman S, Storz G. 2011. Bacterial Small RNA Regulators: Versatile Roles and Rapidly Evolving Variations. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikeda Y, Yagi M, Morita T, Aiba H. 2011. Hfq binding at RhlB-recognition region of RNase E is crucial for the rapid degradation of target mRNAs mediated by sRNAs in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 79:419–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prévost K, Desnoyers G, Jacques J-F, Lavoie F, Massé E. 2011. Small RNA-induced mRNA degradation achieved through both translation block and activated cleavage. Genes Dev, 2011/02/02 ed. 25:385–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lalaouna D, Morissette A, Carrier M-C, Massé E. 2015. DsrA regulatory RNA represses both hns and rbsD mRNAs through distinct mechanisms in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 98:357–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hör J, Gorski SA, Vogel J. 2018. Bacterial RNA Biology on a Genome Scale. Mol Cell 70:785–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han K, Tjaden B, Lory S. 2016. GRIL-seq provides a method for identifying direct targets of bacterial small regulatory RNA by in vivo proximity ligation. Nat Microbiol 2:16239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King AM, Vanderpool CK, Degnan PH. 2019. sRNA Target Prediction Organizing Tool(SPOT) Integrates Computational and Experimental Data To Facilitate Functional Characterization of Bacterial Small RNAs. mSphere 4:e00561–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schachterle JeffreyK, Zeng Q, Sundin GeorgeW. 2019. Three Hfq‐dependent small RNAs regulate flagellar motility in the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora. Mol Microbiol mmi.14232. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Bellows LE, Koestler BJ, Karaba SM, Waters CM, Lathem WW. 2012. Hfq-dependent, co-ordinate control of cyclic diguanylate synthesis and catabolism in the plague pathogen Yersinia pestis. Mol Microbiol 86:661–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng Y, Chen C, Zhao Z, Zhao J, Jacq A, Huang X, Yang Y. 2016. The RNA Chaperone-Hfq Is Involved in Colony Morphology, Nutrient Utilization and Oxidative and Envelope Stress Response in Vibrio alginolyticus. PLOS ONE 11:e0163689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenz DH, Mok KC, Lilley BN, Kulkarni RV, Wingreen NS, Bassler BL. 2004. The Small RNA Chaperone Hfq and Multiple Small RNAs Control Quorum Sensing in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio cholerae. Cell 118:69–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Yan Y, Wu H, Zhou C, Wang X. 2019. Biological and transcriptomic studies reveal hfq is required for swimming, biofilm formation and stress response in Xanthomonas axonpodis pv. citri. BMC Microbiol 19:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyashiro T, Wollenberg MS, Cao X, Oehlert D, Ruby EG. 2010. A single qrr gene is necessary and sufficient for LuxO-mediated regulation in Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 77:1556–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tu KC, Bassler BL. 2007. Multiple small RNAs act additively to integrate sensory information and control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi. Genes Dev 21:221–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bardill JP, Zhao X, Hammer BK. 2011. The Vibrio cholerae quorum sensing response is mediated by Hfq-dependent sRNA/mRNA base pairing interactions. Mol Microbiol 80:1381–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao X, Koestler BJ, Waters CM, Hammer BK. 2013. Post-transcriptional activation of a diguanylate cyclase by quorum sensing small RNAs promotes biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol 89:989–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fidopiastis PM, Miyamoto CM, Jobling MG, Meighen EA, Ruby EG. 2002. LitR, a new transcriptional activator in Vibrio fischeri, regulates luminescence and symbiotic light organ colonization. Mol Microbiol 45:131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. 2011. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, Dufayard J-F, Guindon S, Lefort V, Lescot M, Claverie J-M, Gascuel O. 2008. Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res 36:W465–W469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vincent HA, Henderson CA, Ragan TJ, Garza-Garcia A, Cary PD, Gowers DM, Malfois M, Driscoll PC, Sobott F, Callaghan AJ. 2012. Characterization of Vibrio cholerae Hfq Provides Novel Insights into the Role of the Hfq C-Terminal Region. J Mol Biol 420:56–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsui H-CT, Leung H-CE, Winkler ME. 1994. Characterization of broadly pleiotropic phenotypes caused by an hfq insertion mutation in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Microbiol 13:35–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christiansen JK, Larsen MH, Ingmer H, Søgaard-Andersen L, Kallipolitis BH. 2004. The RNA-Binding Protein Hfq of Listeria monocytogenes: Role in Stress Tolerance and Virulence. J Bacteriol 186:3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robertson GT, Roop RM II. 1999. The Brucella abortus host factor I (HF-I) protein contributes to stress resistance during stationary phase and is a major determinant of virulence in mice. Mol Microbiol 34:690–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arce-Rodríguez A, Calles B, Nikel PI, de Lorenzo V. 2016. The RNA chaperone Hfq enables the environmental stress tolerance super-phenotype of Pseudomonas putida. Environ Microbiol 18:3309–3326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bai G, Golubov A, Smith EA, McDonough KA. 2010. The Importance of the Small RNA Chaperone Hfq for Growth of Epidemic Yersinia pestis, but Not Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, with Implications for Plague Biology. J Bacteriol 192:4239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyell NL, Colton DM, Bose JL, Tumen-Velasquez MP, Kimbrough JH, Stabb EV. 2013. Cyclic AMP Receptor Protein Regulates Pheromone-Mediated Bioluminescence at Multiple Levels in Vibrio fischeri ES114. J Bacteriol 195:5051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyashiro T, Ruby EG. 2012. Shedding light on bioluminescence regulation in Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 84:795–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kimbrough JH, Stabb EV. 2016. Antisocial luxO Mutants Provide a Stationary-Phase Survival Advantage in Vibrio fischeri ES114. J Bacteriol 198:673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bose JL, Kim U, Bartkowski W, Gunsalus RP, Overley AM, Lyell NL, Visick KL, Stabb EV. 2007. Bioluminescence in Vibrio fischeri is controlled by the redox-responsive regulator ArcA. Mol Microbiol 65:538–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Septer AN, Stabb EV. 2012. Coordination of the Arc Regulatory System and Pheromone-Mediated Positive Feedback in Controlling the Vibrio fischeri lux Operon. PLOS ONE 7:e49590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lyell NL, Dunn AK, Bose JL, Stabb E. 2010. Bright Mutants of Vibrio fischeri ES114 Reveal Conditions and Regulators That Control Bioluminescence and Expression of the lux Operon. J Bacteriol 192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lupp C, Ruby EG. 2005. Vibrio fischeri Uses Two Quorum-Sensing Systems for the Regulation of Early and Late Colonization Factors. J Bacteriol 187:3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao H, Kang M, Wang Y, Feng Y, Kong S, Cai X, Ling Z, Chen S, Jiao X, Yin Y. 2018. An essential role for hfq involved in biofilm formation and virulence in serotype 4b Listeria monocytogenes. Microbiol Res 215:148–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parker A, Cureoglu S, De Lay N, Majdalani N, Gottesman S. 2017. Alternative pathways forEscherichia coli biofilm formation revealed by sRNA overproduction. Mol Microbiol 105:309–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brooks JF, Mandel MJ. 2016. The Histidine Kinase BinK Is a Negative Regulator of Biofilm Formation and Squid Colonization. J Bacteriol 198:2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ray VA, Morris AR, Visick KL. 2012. A semi-quantitative approach to assess biofilm formation using wrinkled colony development. J Vis Exp JoVE e4035–e4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Bjelland AM, Sørum H, Tegegne DA, Winther-Larsen HC, Willassen NP, Hansen H. 2012. LitR of Vibrio salmonicida Is a Salinity-Sensitive Quorum-Sensing Regulator of Phenotypes Involved in Host Interactions and Virulence. Infect Immun 80:1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hansen H, Bjelland AM, Ronessen M, Robertsen E, Willassen NP. 2014. LitR is a repressor of syp genes and has a temperature-sensitive regulatory effect on biofilm formation and colony morphology in Vibrio (Aliivibrio) salmonicida. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2014/06/27 ed. 80:5530–5541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tischler AH, Lie L, Thompson CM, Visick KL. 2018. Discovery of Calcium as a Biofilm-Promoting Signal for Vibrio fischeri Reveals New Phenotypes and Underlying Regulatory Complexity. J Bacteriol 200:e00016–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Melamed S, Adams PP, Zhang A, Zhang H, Storz G. 2020. RNA-RNA Interactomes of ProQ and Hfq Reveal Overlapping and Competing Roles. Mol Cell 77:411–425.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beisel CL, Updegrove TB, Janson BJ, Storz G. 2012. Multiple factors dictate target selection by Hfq-binding small RNAs. EMBO J, 2012/03/02 ed. 31:1961–1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iosub IA, van Nues RW, McKellar SW, Nieken KJ, Marchioretto M, Sy B, Tree JJ, Viero G, Granneman S. 2020. Hfq CLASH uncovers sRNA-target interaction networks linked to nutrient availability adaptation. eLife 9:e54655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moriano-Gutierrez S, Bongrand C, Essock-Burns T, Wu L, McFall-Ngai MJ, Ruby EG. 2020. The noncoding small RNA SsrA is released by Vibrio fischeri and modulates critical host responses. PLOS Biol 18:e3000934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Colton DM, Stabb EV. 2016. Rethinking the roles of CRP, cAMP, and sugar-mediated global regulation in the Vibrionaceae. Curr Genet 62:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Lay N, Gottesman S. 2012. A complex network of small non-coding RNAs regulate motility in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 86:524–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sittka A, Pfeiffer V, Tedin K, Vogel J. 2007. The RNA chaperone Hfq is essential for the virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol 63:193–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Romilly C, Hoekzema M, Holmqvist E, Wagner EGH. 2020. Small RNAs OmrA and OmrB promote class III flagellar gene expression by inhibiting the synthesis of anti-Sigma factor FlgM. RNA Biol 17:872–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dial CN, Eichinger SJ, Foxall R, Corcoran CJ, Tischler AH, Bolz RM, Whistler CA, Visick KL. 2021. Quorum Sensing and Cyclic di-GMP Exert Control Over Motility of Vibrio fischeri KB2B1. Front Microbiol 12:690459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vogel J, Luisi BF. 2011. Hfq and its constellation of RNA. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:578–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olejniczak M, Storz G. 2017. ProQ/FinO-domain proteins: another ubiquitous family of RNA matchmakers? Mol Microbiol 104:905–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Attaiech L, Glover JNM, Charpentier X. 2017. RNA Chaperones Step Out of Hfq’s Shadow. Trends Microbiol 25:247–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Visick KL, Hodge-Hanson KM, Tischler AH, Bennett AK, Mastrodomenico V. 2018. Tools for Rapid Genetic Engineering of Vibrio fischeri. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e00850–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barnhart MM, Chapman MR. 2006. Curli Biogenesis and Function. Annu Rev Microbiol 60:131–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holmqvist E, Reimegård J, Sterk M, Grantcharova N, Römling U, Wagner EGH. 2010. Two antisense RNAs target the transcriptional regulator CsgD to inhibit curli synthesis. EMBO J 29:1840–1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bennett BD, Essock-Burns T, Ruby EG. 2020. HbtR, a Heterofunctional Homolog of the Virulence Regulator TcpP, Facilitates the Transition between Symbiotic and Planktonic Lifestyles in Vibrio fischeri. mBio 11:e01624–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sonnleitner E, Moll I, Bläsi U. 2002. Functional replacement of the Escherichia coli hfq gene by the homologue of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology. Microbiology Society. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Fortas E, Piccirilli F, Malabirade A, Militello V, Trépout S, Marco S, Taghbalout A, Arluison V. 2015. New insight into the structure and function of Hfq C-terminus. Biosci Rep 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Santiago-Frangos A, Kavita K, Schu DJ, Gottesman S, Woodson SA. 2016. C-terminaldomain of the RNA chaperone Hfq drives sRNA competition and release of target RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113:E6089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sharma A, Dubey V, Sharma R, Devnath K, Gupta VK, Akhter J, Bhando T, Verma A, Ambatipudi K, Sarkar M, Pathania R. 2018. The unusual glycine-rich C terminus of the Acinetobacter baumannii RNA chaperone Hfq plays an important role in bacterial physiology. J Biol Chem, 2018/07/12 ed. 293:13377–13388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Malabirade A, Morgado-Brajones J, Trépout S, Wien F, Marquez I, Seguin J, Marco S,Velez M, Arluison V. 2017. Membrane association of the bacterial riboregulator Hfq and functional perspectives. Sci Rep 7:10724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boettcher KJ, Ruby EG. 1990. Depressed light emission by symbiotic Vibrio fischeri of the sepiolid squid Euprymna scolopes. J Bacteriol 172:3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stabb EV, Reich KA, Ruby EG. 2001. Vibrio fischeri Genes hvnA and hvnB Encode Secreted NAD+-Glycohydrolases. J Bacteriol 183:309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davis R, Botstein D, Roth J. 1980. Advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Har-bor Laboratory. N Y. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Christensen DG, Tepavčević J, Visick KL. 2020. Genetic Manipulation of Vibrio fischeri. Curr Protoc Microbiol 59:e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.DeLoney-Marino CR, Wolfe AJ, Visick KL. 2003. Chemoattraction of Vibrio fischeri to Serine, Nucleosides, and Acetylneuraminic Acid, a Component of Squid Light-Organ Mucus. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:7527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 25:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Madeira F, Park YM, Lee J, Buso N, Gur T, Madhusoodanan N, Basutkar P, Tivey ARN, Potter SC, Finn RD, Lopez R. 2019. The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res 47:W636–W641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brooks JF, Gyllborg MC, Cronin DC, Quillin SJ, Mallama CA, Foxall R, Whistler C, Goodman AL, Mandel MJ. 2014. Global discovery of colonization determinants in the squid symbiont Vibrio fischeri. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111:17284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.