Abstract

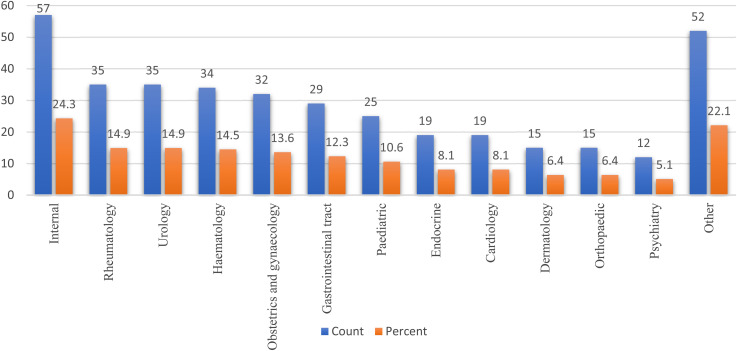

Despite the increasing use of telemedicine, patients’ views on telemedicine remain unclear. This study aimed to understand factors affecting patient perceptions and satisfaction with telemedicine services. 235 patients were surveyed on accessibility to telemedicine clinics, medical specialities and satisfaction with the services. 58.3% confirmed having a stable internet connection, 24.3% used telemedicine services in internal medicine clinics, and only 5.1% accessed the telemedicine services in psychiatry clinics. 68.5% used the telephone to access telemedicine service, while only 6.4% used the hotline. Over half of patients confirmed their ability to hear clearly and speak easily with their healthcare providers during their consultations. 55.7% confirmed they were satisfied with their telemedicine experience, while 23.4% were neutral and 8.9% were unsatisfied. There was a significant difference in the rates of satisfaction between female and male respondents (p-value<0.001). Those with stable internet connection had significantly higher satisfaction rates with telemedicine services (p-value<0.001). The rates of satisfaction with telemedicine services were significantly higher in Cardiology and Orthopaedic clinics. Larger multi-center studies examining other factors affecting patients’ satisfaction are recommended.

Keywords: Access to Care, challenges, patient Satisfaction, telemedicine, health Information Technology

Introduction

Telemedicine enables remote delivery of healthcare using technology to communicate rapidly and limit the need for patients’ physical attendance in clinic, increasing cost-effectiveness, improving access to care and medical information, increasing quality of services and patient satisfaction (1–3). Telemedicine is beneficial for all stakeholders; providers, patients, and the healthcare service and can be offered via telephone, chat mechanisms, video, or other electronic means (4). The technology and understanding of telemedicine are continuously improving, integrating new advancements, and adapting to evolving health contexts and population health needs (5).

The monitoring of chronic conditions while minimizing non-urgent hospital visits, especially among children and vulnerable populations, has been made possible using telemedicine applications (2). Medical care is being taken into patient’s homes, satisfying their needs (6). Telemedicine helps to provide information promptly, reduce the time needed to deliver medications, track patients samples with the laboratories, carry out radiology tests and complete other routine healthcare tasks. Patients can schedule appointments online or request prescription refills remotely, reducing the likelihood of no-show, or lack of adherence to medication regimens (7).

In 2011, the Ministry of Health (MOH) in Saudi Arabia initiated the first national telemedicine project known as the Saudi Telemedicine Network (STN) and dedicated massive resources to offer citizens and residents quality health services and expand the scope of telehealth. Telemedicine regulations were issued by the MOH in 2018, clarifying requirements for licensing and accreditation (8,9). The Telemedicine Excellence Unit operates under the Saudi Health Council (SHC) and the National Health Information Centre (NHIC) and is responsible for telemedicine monitoring and control, directing, assisting, tracking and evaluating the implementation and development of telemedicine in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (10). Legislation that regulates confidentiality, personal privacy, access and security must be enhanced. Ethical issues of confidentiality, dignity, and privacy in the use of telemedicine information and communications technology must also be considered. The regulations currently require that all healthcare providers receive training in the use these services and that the training be approved by the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCFHS). The telemedicine training should include education on legislation and specialized applications to provide care remotely. The Kingdom's Vision 2030 was designed to accelerate the technological innovation and evolution of the health system and promote public-private partnerships to boost clinical and financial performance and improve patient care and emphasize the value of a national telemedicine network and the processes to enhance it (11,12).

During COVID-19, telemedicine proved to be a viable means of delivering healthcare services, reducing rates of clinic closures, appointment cancellations, despite physical distancing requirements and effectively reducing the risk of virus transmission. Telemedicine applications were vital in supporting public health precautions, reducing risk while maintaining high standards of care. Electronic databases and telecommunications facilitated health services and mobile (mHealth) applications were introduced (e.g., Sehatty, Mawid, Tawakklna, Tabaud, and Tetamman) improving the delivery of healthcare and increasing patient satisfaction (3,13).

The Saudi health care system faces challenges to ensure telemedicine services align with the mission, vision and strategies of healthcare organizations in implementing telemedicine and reconfiguring service delivery and increasing access for rural areas (14,15). Many public and private sector hospitals have contracted with suppliers, purchasing remote patient management consultation capabilities. Other challenges facing the system are healthcare providers’ ability and willingness to utilize telemedicine platforms, patient’s acceptance, and willingness to use or engage with the telemedicine platforms as well as issues with implementation, maintenance of telemedicine platforms by healthcare information technology experts, and issues of security, privacy, reliability, and supportability (16,17). There are also significant cultural and societal restrictions (i.e., compatibility with Islamic ethics, laws and Saudi social norms and traditions). Issues with computer literacy and resistance to adopting new systems are other obstacles to successful telemedicine implementation and use. Language barriers are another. Arabic is the first language of most patients while the systems implemented are largely developed in English and translation of these systems is a programming challenge.

The technical skills and expertise of healthcare providers are key factors to be considered as part of hospital information system implementation plans. Building health provider capacity and skills in using health technology increases patients access to quality healthcare (18). Organizations must enhance training programs for healthcare providers in the smooth delivery of telemedicine services, with the recognition that providers increasingly prefer flexible training and education opportunities in the form of virtual webinars and video conferencing (19). Another key factor is the uptake and engagement of patients with telemedicine. Appropriate use by patients can achieve the objectives of patient safety and quality of care, despite the remote service provision. Proper understanding of telemedicine technology is critical; if patients are supported and encouraged in its use, they will have greater confidence and satisfaction in the system, leading to improved health outcomes (20–24).

Methodology

The study measured patient satisfaction with telemedicine services, highlighting current strengths and weaknesses, and the importance of training of health providers in its use and supporting patients.

Study Design and Instrument

A cross-sectional survey using a questionnaire design, based on a previously developed study instrument for Patient Satisfaction with Telemedicine used by Le et al. (2019) which combined both the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18) originally developed by Marshall et al., 1994 and the Telemedicine Satisfaction Questionnaire (TSQ) developed by Yip et al., 2003 and used with permission from Le et al. with minor modifications for our context (20). We conducted a small pilot study in the hospital for validation purposes. The questionnaire consisted of 14 questions using a five-point Likert scale ranging from (5) “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” about the personal experience of the patient using telemedicine services in clinic. The questionnaire was divided into three domains: (1) Quality of Care provided (2) Similarity to Face-to-Face Encounters (3) Perception of the Interaction.

Study Setting

The study was conducted at Qatif Central Hospital (QCH) in Saudi Arabia. This hospital plays a vital role in supporting tertiary healthcare in the region with a capacity of 360 beds. QCH uses multiple methods to provide telemedicine services such as communication via WhatsApp for inquiries, booking appointments and receiving test results, a website for re-dispensing medications or delivery to the patient’s home or primary healthcare centres, a virtual clinic established during the COVID-19 pandemic, and a hotline to answer patients over the phone, and the regular telephone reception services for appointment bookings or inquiries. The questionnaire was sent to patients in the hospital through two departments: Pharmacy and Outpatient Department with multiple specialties such as internal medicine, rheumatology, urology, hematology, obstetrics and gynecology, gastrointestinal medicine, pediatrics, endocrinology, cardiology, dermatology, orthopedics, psychiatry, and other specialties. The questionnaire was distributed utilizing the hospital patient database and sent through WhatsApp from the hospital to patients directly.

Study Population and Sample Size

The study population of interest were adult patients (male and female) in the hospital patient database who had contact with the hospital during the past year (during COVID-19) - thereby potentially using the telemedicine services at QCH - from all OPD departments and Pharmacy at the time of the study. We received permission to send the survey to 800 randomly selected patients from the database. We estimated 300 patient respondents to the survey.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis was carried out for categorical variables using counts and percentages, as no numerical variables were included in the dataset. Chi-square testing was use for comparison of categorical variables at level of significance P > 0.05. Data analysis was carried out using SPSS version 26.

Ethical Approval Considerations

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from the appropriate authorities at QCH on 7/3/2021 with the reference number (QCH-SREC0 256/2021). The study was conducted in full accordance with the protocol and current revision of the Declaration of Helsinki for Good Clinical Practice. Participation consent was obtained voluntarily through respondents clicking yes/no at the outset of the online survey after reading a brief description of the study. Contact information for the study investigator was provided. No personal identifying information for the respondents was requested or obtained, including IP addresses. No data was used for any purpose other than what was stated. Respondents were permitted to exit the study without any adverse effect. The investigators maintain security of the data collected as no other parties are provided access to study information.

Results

503 patients responded to the survey (62.8%) . Of those, 235 respondents had used the telemedicine services recently and were able to answer all the survey questions and were as such eligible for inclusion in the analysis. Other respondents were excluded.

General Characteristics of Respondents

76.2% of respondents were female. 34% were between 38 to 47 years old, and 6.8% were above 60 years old. In terms of educational level, 57.9% had a university degree, while only 3.4% had a degree from intermediate school (below high school) (See Table 1).

Table 1.

General Characteristics of Respondents.

| Count | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 56 | 23.8 |

| Female | 179 | 76.2 | |

| Age Group | 18-27 | 45 | 19.1 |

| 28-37 | 63 | 26.8 | |

| 38-47 | 80 | 34.0 | |

| 48-57 | 31 | 13.2 | |

| 60 + | 16 | 6.8 | |

| Educational Level | Elementary school | 14 | 6.0 |

| Intermediate school | 8 | 3.4 | |

| High school | 64 | 27.2 | |

| University | 136 | 57.9 | |

| Graduate study | 13 | 5.5 |

Access to Telemedicine

Respondents were asked about access to different telemedicine services, the stability of their internet connection supporting their access to the services. 58.3% confirmed having a stable internet connection, with 17% strongly agreeing. 5.1% disagreed, and 2.1% strongly disagreed about having a stable internet connection to access telemedicine services (See Table 2, Table 4).

Table 2.

Access to Telemedicine.

| Count | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you have stable internet to support your access to telemedicine services? | Strongly Agree | 40 | 17.0 |

| Agree | 137 | 58.3 | |

| Neutral | 41 | 17.4 | |

| Disagree | 12 | 5.1 | |

| Strongly Disagree | 5 | 2.1 | |

| Which healthcare clinic did you attend using telemedicine? | Internal | 57 | 24.3 |

| Rheumatology | 35 | 14.9 | |

| Urology | 35 | 14.9 | |

| Hematology | 34 | 14.5 | |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 32 | 13.6 | |

| Gastrointestinal | 29 | 12.3 | |

| Pediatrics | 25 | 10.6 | |

| Endocrine | 19 | 8.1 | |

| Cardiology | 19 | 8.1 | |

| Dermatology | 15 | 6.4 | |

| Orthopedic | 15 | 6.4 | |

| Psychiatry | 12 | 5.1 | |

| Other | 52 | 22.1 | |

| Which type of telemedicine did you use? | Telephone | 161 | 68.5 |

| Online prescription services | 61 | 26.0 | |

| WhatsApp messaging | 46 | 19.6 | |

| Virtual clinic | 42 | 17.9 | |

| Hotline | 15 | 6.4 |

Table 4.

Factors Affecting Patient’s Satisfaction with Telemedicine.

| Overall, I am satisfied with the quality of service being provided via telemedicine. | P-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |||

| Gender | Male | 17.9% | 39.3% | 10.7% | 3.6% | 28.6% | <0.001 |

| Female | 12.8% | 42.5% | 27.4% | 10.6% | 6.7% | ||

| Age group | 18-27 | 13.3% | 42.2% | 28.9% | 11.1% | 4.4% | 0.270 |

| 28-37 | 17.5% | 36.5% | 25.4% | 9.5% | 11.1% | ||

| 38-47 | 11.3% | 42.5% | 22.5% | 7.5% | 16.3% | ||

| 48-57 | 9.7% | 58.1% | 19.4% | 9.7% | 3.2% | ||

| 60 + | 25.0% | 25.0% | 12.5% | 6.3% | 31.3% | ||

| Educational level | Elementary school | 14.3% | 28.6% | 21.4% | 21.4% | 14.3% | 0.063 |

| Intermediate school | 12.5% | 50.0% | 12.5% | 25.0% | 0.0% | ||

| High school | 18.8% | 43.8% | 20.3% | 7.8% | 9.4% | ||

| University | 10.3% | 44.1% | 27.2% | 7.4% | 11.0% | ||

| Graduate study | 30.8% | 15.4% | 7.7% | 7.7% | 38.5% | ||

| Do you have stable internet to support your access to telemedicine services? | Strongly agree | 37.5% | 40.0% | 5.0% | 7.5% | 10.0% | <0.001 |

| Agree | 11.7% | 48.9% | 21.2% | 8.0% | 10.2% | ||

| Neutral | 2.4% | 26.8% | 48.8% | 7.3% | 14.6% | ||

| Disagree | 8.3% | 25.0% | 25.0% | 16.7% | 25.0% | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0.0% | 20.0% | 20.0% | 40.0% | 20.0% | ||

| Which healthcare clinic did you attend using telemedicine? | Internal | 33.3% | 25.0% | 16.7% | 8.3% | 16.7% | 0.047 |

| Rheumatology | 33.3% | 25.0% | 16.7% | 8.3% | 16.7% | ||

| Urology | 28.6% | 71.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | ||

| Hematology | 23.1% | 46.2% | 15.4% | 7.7% | 7.7% | ||

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 15.4% | 46.2% | 38.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 28.6% | 35.7% | 14.3% | 0.0% | 21.4% | ||

| Pediatric | 0.0% | 60.0% | 20.0% | 20.0% | 0.0% | ||

| Endocrine | 0.0% | 16.7% | 66.7% | 16.7% | 0.0% | ||

| Cardiology | 20.0% | 80.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | ||

| Dermatology | 0.0% | 60.0% | 20.0% | 20.0% | 0.0% | ||

| Orthopedic | 0.0% | 80.0% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | ||

| Psychiatry | 0.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | ||

| Other | 0.0% | 37.5% | 20.8% | 20.8% | 20.8% | ||

| Which type of telemedicine did you use? | Telephone | 12.3% | 42.5% | 25.5% | 7.5% | 12.3% | 0.496 |

| Online prescription services | 16.7% | 41.7% | 33.3% | 0.0% | 8.3% | ||

| WhatsApp messaging | 29.4% | 23.5% | 17.6% | 23.5% | 5.9% | ||

| Virtual clinic | 5.0% | 50.0% | 30.0% | 5.0% | 10.0% | ||

| Hotline | 10.0% | 40.0% | 30.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | ||

Multiple clinics were identified as offering telemedicine services. When asked about the clinic they accessed using telemedicine services, the highest rate of use (24.3%) was in internal medicine, while the lowest rate of use (only 5.1%) was in psychiatry (See Table 2, Table 4, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Attended Clinics with Telemedicine

Respondents used various methods to access telemedicine services including telephone, online prescription services, WhatsApp messaging, virtual clinics, and the hotline. More than half of respondents (68.5%) used the telephone to access telemedicine service, while only 6.4% used the hotline (see Table 2).

Views on the Telemedicine Experience

When asked about the benefits of telemedicine, half of respondents (50.6%) agreed that they could talk easily to their healthcare providers, and 54.5% agreed they could hear their healthcare providers clearly during their telemedicine consultation. 47.2% agreed their healthcare providers are able to understand their health conditions and needs via telemedicine. However, there were equally conflicting opinions about whether telemedicine offered patients the same level of experience in seeing healthcare providers virtually as if they were in person in the clinic, where 26.4% agreed and 26.8% disagreed (See Table 3).

Table 3.

Opinions about Telemedicine Experience

| Count | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| I can easily talk to my healthcare provider | Strongly agree | 42 | 17.9 |

| Agree | 119 | 50.6 | |

| Neutral | 35 | 14.9 | |

| Disagree | 22 | 9.4 | |

| Strongly disagree | 17 | 7.2 | |

| I can hear my healthcare provider clearly | Strongly agree | 48 | 20.4 |

| Agree | 128 | 54.5 | |

| Neutral | 26 | 11.1 | |

| Disagree | 20 | 8.5 | |

| Strongly disagree | 13 | 5.5 | |

| My healthcare provider is able to understand my healthcare condition | Strongly agree | 45 | 19.1 |

| Agree | 111 | 47.2 | |

| Neutral | 49 | 20.9 | |

| Disagree | 17 | 7.2 | |

| Strongly disagree | 13 | 5.5 | |

| I can see my healthcare provider as if we met in person | Strongly agree | 24 | 10.2 |

| Agree | 62 | 26.4 | |

| Neutral | 53 | 22.6 | |

| Disagree | 63 | 26.8 | |

| Strongly disagree | 33 | 14.0 | |

| I do not need assistance while using the system | Strongly agree | 39 | 16.6 |

| Agree | 101 | 43.0 | |

| Neutral | 50 | 21.3 | |

| Disagree | 26 | 11.1 | |

| Strongly disagree | 19 | 8.1 | |

| I feel comfortable communicating with my healthcare provider | Strongly agree | 40 | 17.0 |

| Agree | 113 | 48.1 | |

| Neutral | 42 | 17.9 | |

| Disagree | 24 | 10.2 | |

| Strongly disagree | 16 | 6.8 | |

| I think the healthcare provided via telemedicine is consistent | Strongly agree | 24 | 10.2 |

| Agree | 76 | 32.3 | |

| Neutral | 76 | 32.3 | |

| Disagree | 38 | 16.2 | |

| Strongly disagree | 21 | 8.9 | |

| I obtain better access to healthcare services by use of telemedicine | Strongly agree | 23 | 9.8 |

| Agree | 67 | 28.5 | |

| Neutral | 69 | 29.4 | |

| Disagree | 48 | 20.4 | |

| Strongly disagree | 28 | 11.9 | |

| Telemedicine saves me time traveling to a hospital or specialist clinic | Strongly agree | 51 | 21.7 |

| Agree | 106 | 45.1 | |

| Neutral | 50 | 21.3 | |

| Disagree | 16 | 6.8 | |

| Strongly disagree | 12 | 5.1 | |

| I do not receive adequate attention | Strongly agree | 22 | 9.4 |

| Agree | 58 | 24.7 | |

| Neutral | 53 | 22.6 | |

| Disagree | 74 | 31.5 | |

| Strongly disagree | 28 | 11.9 | |

| Telemedicine provides for my healthcare need | Strongly agree | 28 | 11.9 |

| Agree | 84 | 35.7 | |

| Neutral | 68 | 28.9 | |

| Disagree | 31 | 13.2 | |

| Strongly disagree | 24 | 10.2 | |

| I find telemedicine an acceptable way to receive healthcare services | Strongly agree | 29 | 12.3 |

| Agree | 86 | 36.6 | |

| Neutral | 59 | 25.1 | |

| Disagree | 38 | 16.2 | |

| Strongly disagree | 23 | 9.8 | |

| I will use telemedicine services again | Strongly agree | 33 | 14.0 |

| Agree | 85 | 36.2 | |

| Neutral | 62 | 26.4 | |

| Disagree | 28 | 11.9 | |

| Strongly disagree | 27 | 11.5 |

As for assistance, 43% of respondents confirmed needing assistance to use telemedicine services. 48.1% agreed they were comfortable about communicating with their healthcare providers using telemedicine. 29.4% of respondents were neutral as to whether telemedicine improved their access to healthcare services. Furthermore, 32.3% agreed the healthcare provided via telemedicine was consistent, while a similar proportion was neutral. In terms of time saving, 45.1% agreed that telemedicine saves time and money for traveling to hospital or specialized clinics, and 35.7% agreed the telemedicine services provide them with their healthcare needs. A similar proportion of responses (36.6%) mentioned that they found telemedicine an acceptable way to receive healthcare services, and 36.2% will use the telemedicine services again in the future. 24.7% of respondents indicated that the only drawback of the telemedicine service was the patient not receiving adequate attention but 31.5% disagreed (See Table 3).

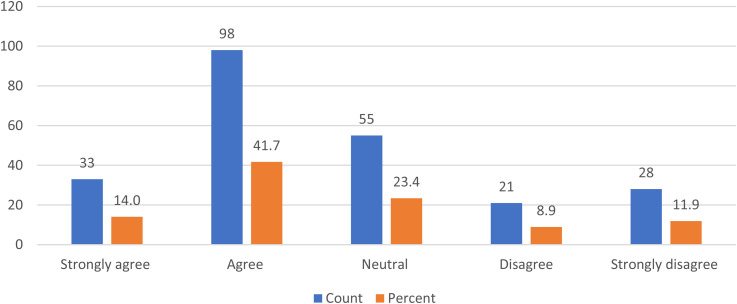

Satisfaction with the Quality of Telemedicine Service

The highest proportion of respondents (41.7%) agreed they were satisfied with their telemedicine service experience and 14% strongly agreed, which indicates a majority satisfaction rate of 55.7%. 23.4% were neutral and 8.9% were unsatisfied by the service (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Satisfaction with Provided Services

Factors Affecting Patient’s Satisfaction with Telemedicine

To identify key contributors to patient’s satisfaction towards telemedicine services provided by outpatient clinics, responses to overall satisfaction rate were compared over different demographic variables (gender, age groups, educational levels, and access to telemedicine variables, including stable internet connection, clinics attended through telemedicine, and the type of telemedicine used. We found a significant difference between males and females in terms of their satisfaction towards telemedicine, where females agreed significantly more at P-value<0.001. Similarly, internet connection stability also impacts the patient satisfaction rate, as respondents who had a stable internet connection to support access to telemedicine services, had a significantly higher likelihood of being satisfied with the telemedicine services at p-value<0.001. The type of medical specialty was also found to significantly impact patient satisfaction rates, where cardiology and orthopedic clinics had the highest agreement among patients about being satisfied with telemedicine services at p-value = 0.047. Type of telemedicine, age groups, and educational levels failed to show any statistically significant difference in terms of overall satisfaction towards telemedicine services (See Table 4).

Discussion

Telemedicine is rapidly gaining acceptance as an advance in healthcare service provision that can transform the quality of medical care, particularly in out-patient clinics although not widely implemented yet in all healthcare institutions in Saudi Arabia. Recent studies found patient satisfaction with telemedicine services was increasing (20–24).

Our study measured patient satisfaction with telemedicine services, highlighting current strengths and weaknesses, and the importance of training of health providers in its use and supporting patients. We found high satisfaction rates among patients towards telemedicine services (55.7%) were satisfied with the services, with only 8.9% unsatisfied. Over half of patient respondents agreed that telemedicine services increased access to healthcare and facilitated communication with healthcare providers.

Satisfaction with telemedicine services has been investigated in different contexts. Poulsen et al. 2015 examined the satisfaction of patients receiving telemedicine services in a rheumatology clinic in a rural region, using a prospective cross-sectional survey with two groups of patients: the first group with access to telemedicine services, and the second group using traditional face to face visits. They found that patients in the telemedicine group were satisfied with the service quality but did not find significant differences between patients who used telemedicine services and the face-to-face group (22).

In our study, similar to Poulsen et al. 2015, we found a high satisfaction rate among the users of the telemedicine services. Although Poulsen et al. 2015 did not explore factors affecting patient satisfaction with telemedicine, we examined several factors: gender, stability of internet connection, and clinic specialty offering telemedicine services. Being female, having a stable internet connection, and accessing cardiology or orthopaedics clinics all showed significantly higher patient satisfaction rates compared to others (p-value <0.05).

A recent systematic review by Atmojo et al. 2020 on the satisfaction of patients and cost effectiveness of telemedicine services revealed that telemedicine services reduce the need for patients to travel, which saves them money; and reduce their absence from work to attend face-to-face visits in the clinic. Additionally, telemedicine services were able to demonstrate significant healthcare cost savings in particular specialties such as paediatrics (23). These findings were also supported by Al-Samarraie et al., 2020 who found that use of telemedicine services reduced the likelihood of patient no-show, or lack of adherence to medication regimens (2).

Although the present study did not evaluate cost-effectiveness, we did find 45.1% of patient respondents agreed that telemedicine services could save them time and money in traveling to clinics. We did not find a significantly higher satisfaction rate for patients attending paediatric clinics in line with Atmojo et al. (2020), however, we note that only 10.6% of patient respondents attended telemedicine service in a paediatric clinic, which may explain why the study could not detect a significant difference.

Muller et al., 2017 measured patient satisfaction using telemedicine services. The study, a randomized controlled trial, uniquely examined satisfaction longitudinally in one specialty, a neurology outpatient clinic for 279 patients using telemedicine services for treatment and follow-up of non-acute headache attacks over one year. The study demonstrated that females were significantly more satisfied with the service compared to males (p-value = 0.027), while age group and educational levels did not influence patient’s satisfaction. Even after one year, patients receiving telemedicine service did not have lower satisfaction than those having conventional clinic visits (24).

Our study findings support Muller et al., 2017 where females were significantly more satisfied compared to males, but age group and level of education did not significantly influence patient satisfaction. One advantage of our study is that we explored patients’ views on using telemedicine services in a variety of clinics and specialities, which increases the generalizability of our findings. We conclude there is a high rate of patient satisfaction with telemedicine services, with ease of use, ability to communicate and engage with healthcare providers, consistency of the services, decreasing need to travel and increasing access, as meeting patient’s healthcare needs.

Patients were confident and comfortable about continuing to use telemedicine services in the future. Only a minority of patients were dissatisfied, and this should be taken into consideration when working to improve telemedicine services. Over one quarter (34%) of patients felt they did not receive the level of adequate attention they were expecting from the service. This finding should encourage the expansion of implementation of telemedicine services to other departments.

The present study had several limitations; the relatively small sample size may not fully represent all telemedicine service users in Saudi Arabia; therefore, larger studies are needed. Also, the study was carried out in only one city and one healthcare facility; multi-center studies in Saudi Arabia are advised. Furthermore, we only assessed demographic factors of age, education and gender, and we note the higher percentage of respondents who were female and had university level education, which may be unique to the geographical region, but other factors may also impact patient satisfaction with telemedicine.

Recommendations and Conclusion

We recommend the expansion in offering telemedicine services to departments with long waiting lists or as an option for patients who have to travel to be able to attend. Telemedicine services should be readily available for clinics that do not necessitate physical examination, such as psychiatry clinics. Telemedicine may be prioritized for follow-up, where the patient has had a physical examination initially and is not required for the follow-up.

Although our findings highlight the significance of telemedicine services and a high satisfaction rate among patients, larger studies are needed to expand upon these findings. Other patient variables might be considered to further evaluate satisfaction levels, including sociodemographic information such as income levels, employment and marital status, medical history, medical presentation or co-morbidities that patients may have and whether they presented to the clinic with an acute condition or chronic condition.

It is also possible to develop or implement telemedicine technology that does not depend heavily on internet connections or can be operated offline to increase accessibility for patients who do not have stable internet service.

The awareness of patients and willingness to use telemedicine services should be further considered. Patients should be informed and encouraged to use telemedicine. Patient education and support campaigns can be implemented in primary care clinics, hospital common areas, and upon discharge or via text messaging or patient portals or using banners or posters in healthcare facilities to inform patients of the services and how to access them.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to extend their appreciation to the Pharmacy and Outpatients Department staff at Qatif Central Hospital for their support during this research work.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: SA Abdulwahab https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1990-263X

References

- 1.Cassoobhoy A. What Is Telemedicine? How Does Telehealth Work? 2020 Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/lung/how-does-telemedicine-work.

- 2.Al-Samarraie H, Ghazal S, Alzahrani AI, Moody L. Telemedicine in middle eastern countries: progress, barriers, and policy recommendations. Int J Med Inform. 2020;141(104232):104232. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdel Nasser A, Mohammed Alzahrani R, Aziz Fellah C, Muwafak Jreash D, Talea A, Almuwallad N, et al. Measuring the patients’ satisfaction about telemedicine used in Saudi Arabia during COVID-19 pandemic. Cureus. 2021;13(2):e13382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NHIC (2018) Retrieved from https://nhic.gov.sa/en/Initiatives/Documents/Saudi Arabia Telemedicine Policy.pdf

- 5.Alshammari F, Hasan S. Perceptions, preferences and experiences of telemedicine among users of information and communication technology in Saudi Arabia. J Health Inform Dev Ctries. 2019;201(1):13. Retrieved from https://jhidc.org/index.php/jhidc/article/view/240. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maeder A, Poultney N. Evaluation strategies for telehealth implementations. IEEE International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI). 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine. The Role of Telehealth in an Evolving Health Care Environment: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2012 Nov 20. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207145/ doi: 10.17226/13466. [PubMed]

- 8.Central Information Commission (CIC). Saudi Arabia's Ministry of Health Introduces “Health App” that connects all Saudis, regardless of location, with healthcare providers. 2018. Retrieved from https://cic.org.sa/2018/03/saudi-arabias-ministry-health-introduces-health-app-connects-saudis-regardless-location-healthcare-providers.

- 9.Al-Thebiti AA, Al Khatib FM, Al-Ghalayini NA. Telemedicine: between reality and challenges in jeddah hospitals. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2017;68(3):1381-9. doi: 10.12816/0039678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MOH. National E-Health Strategy. https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/nehs/Pages/The-Roadmap-of-Projects.aspx. 2013.

- 11. Vision 2030 in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Opportunities for Public Private Collaborations. 2020, November 30. Retrieved from https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/emea/saudi-arabias-vision-2030-opportunities-public-private-collaborations.

- 12.MOH (2020) Telemedicine https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Information-and-services/Pages/Telemedicine.aspx

- 13.Gachabayov M, Latifi LA, Parsikia A, Latifi R. Current state and future perspectives of telemedicine use in surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review protocol. Int J Surg Protoc. 2020;24(24):17-20. doi: 10.1016/j.isjp.2020.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bali S. Barriers to Development of Telemedicine in Developing Countries. In: Telehealth.IntechOpen; 2018. https://www.intechopen.com/books/telehealth/barriers-to-development-of-telemedicine-in-developing-countries.

- 15.Alghamdi SM, Alqahtani JS, Aldhahir AM. Current Status of telehealth in Saudi Arabia during COVID-19. J Family Community Med. 2020;27(3):208-11. doi: 10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_295_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Using Telehealth to Expand Access to Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/telehealth.html.

- 17.Alaboudi A, Atkins A, Sharp B, Balkhair A, Alzahrani M, Sunbul T. Barriers and challenges in adopting Saudi telemedicine network: the perceptions of decision makers of healthcare facilities in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2016;9(6):725-33. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO: TELEMEDICINE. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_telemedicine_2010.pdf. 2021.

- 19.Kissi J, Dai B, Dogbe CS, Banahene J, Ernest O. Predictive factors of physicians’ satisfaction with telemedicine services acceptance. Health Informatics J. 2020;26(3):1866-80. doi: 10.1177/1460458219892162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le LB, Rahal HK, Viramontes MR, Meneses KG, Dong TS, Saab S. Patient satisfaction and healthcare utilization using telemedicine in liver transplant recipients. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(5):1150-7. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5397-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almathami HKY, Win KT, Vlahu-Gjorgievska E. Barriers and facilitators that influence telemedicine-based, real-time, online consultation at patients’ homes: systematic literature review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(2):e16407. doi: 10.2196/16407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poulsen KA, Millen CM, Lakshman UI, Buttner PG, Roberts LJ. Satisfaction with rural rheumatology telemedicine service. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;18(3):304-14. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atmojo JT, Sudaryanto WT, Widiyanto A, Ernawati E, Arradini D. Telemedicine, cost effectiveness, and patient’s satisfaction: a systematic review. J Health Pol Manag. 2020;5(2):103-7. doi: 10.26911/thejhpm.2020.05.02.02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Müller KI, Alstadhaug KB, Bekkelund SI. Headache patients’ satisfaction with telemedicine: a 12-month follow-up randomized non-inferiority trial. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24(6):807-15. doi: 10.1111/ene.13294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]