Abstract

Electrochemical devices that transform electrical energy to mechanical energy through an electrochemical process have numerous applications ranging from soft robotics and micropumps to autofocus microlenses and bioelectronics. To date, achievement of large deformation strains and fast response times remains a challenge for electrochemical actuator devices operating in liquid wherein drag forces restrict the actuator motion and electrode materials/structures limit the ion transportation and accumulation. We report results for electrochemical actuators, electrochemical mass transfers, and electrochemical dynamics made from organic semiconductors (OSNTs). Our OSNTs electrochemical device exhibits high actuation performance with fast ion transport and accumulation and tunable dynamics in liquid and gel-polymer electrolytes. This device demonstrates an excellent performance, including low power consumption/strain, a large deformation, fast response, and excellent actuation stability. This outstanding performance stems from enormous effective surface area of nanotubular structure that facilitates ion transport and accumulation resulting in high electroactivity and durability. We utilize experimental studies of motion and mass transport along with the theoretical analysis for a variable–mass system to establish the dynamics of the electrochemical device and to introduce a modified form of Euler-Bernoulli’s deflection equation for the OSNTs. Ultimately, we demonstrate a state-of-the-art miniaturized device composed of multiple microactuators for potential biomedical application. This work provides new opportunities for next generation electrochemical devices that can be utilized in artificial muscles and biomedical devices.

Keywords: Organic semiconductors, nanotubes, liquid and gel-polymer electrolytes

Graphical Abstract

Electrochemical devices have numerous applications ranging from soft robotics to organic electronics. However, the design of durable and fast responsive actuators with large deformations remains a challenge for electrochemical actuators operating in liquid. Here, we present a high-performance device based on organic semiconductor nanotubes (OSNTs) that exhibits very low power consumption/strain, large deformations, fast responses, and excellent actuation stability in liquid and gel-polymer electrolytes.

1. Introduction

Ions play a key role in the life of living organisms, particularly for nerve signal transduction that is essential for contractile cells to produce muscle deformation and/or motion.[1] Inspired by function of biological muscle, artificial muscles concerning ion migration into/out of electrodes (e.g. ionic polymer-metal composites) have gained much attention in biomimetic technologies.[2] Soft ionic actuators, also called electrochemical actuators, generate actuation deformation in response to applied voltage (below 1 V and up to several volts) by reversible intercalation and deintercalation of ions into/out of an electroactive layer. Such actuators have been intensively investigated for various applications in soft robotics, artificial muscles, autofocus lenses, and biomedical devices.[2a, 3] One group of these actuators is air-working electrochemical actuators that are composed of one semipermeable ion-conductive electrolyte polymer membrane sandwiched between two electroactive layers.[4] This type of actuators often utilizes conductive carbon nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes,[5] graphene,[6] and graphdiyne.[7] Recent advances in materials science and fabrication techniques have enabled development of durable and lightweight air working electrochemical actuators capable of generating large strains and fast responses.[8] Most of these actuators are however, composed of multiple electroactive materials and thus, require rather complex fabrication processes.

Another group of electrochemical actuators are those that operate in an ion-conductive electrolyte. These actuators are commonly composed of an electroactive film layer deposited on an electrode to construct a bilayer actuator device. The volume change of the electroactive layer in a bilayer configuration can be used to generate out-of-plain movement and produce bending deformation.[9] Among materials that have been utilized as the electroactive layer in these actuators, organic semiconductors (OSs) (i.e. π-conjugated polymers (CPs)) such as polyaniline, polypyrrole, and poly3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene, exhibit unique properties as they can operate under low voltages and hold strain under voltage or open circuit.[10] OS films with controlled thickness can be electrochemically synthesized and miniaturized, making them versatile for various applications such as medical devices and artificial muscles.[11] The volume changes in OS actuators is governed by transportation of ions and solvent molecules under redox reactions.[12] Owing to their good biocompatibility, OSs have been used in biomedical devices and actuators operating in biofluids.[3d, 11b, 13] Among OSs, polypyrrole has been extensively studied for electrochemical actuators as it can withstand relatively large actuation strains/stresses and be readily electrodeposited to form dense or porous films in aqueous and organic electrolytes for large scale production.[14] However, achievement of large deformation strains with fast response time and high actuation stability remains a challenge for OS film-based actuators wherein the high rigidity and dense structure of the film restrict the actuator motion, limit the ion transportation, and increase the risk of delamination.[15]

In the light of our previous studies showing that OS nanofibers and nanotubes significantly enhanced the performance of microelectrodes for detection of biomolecules and recording of biosignals,[13e, 16] here we hypothesize that OS nanotubes promotes the performance of OS-based electrochemical devices through the large effective surface area of nanotubes that facilitates ion diffusion and accumulation. In this work, for the first time, we designed and developed a high-performance electrochemical device made of OS nanotubes (OSNTs) and reports results for electrochemical actuators, electrochemical mass transfers, and electrochemical dynamics. We assess the performance of OSNTs device within two distinct electrolytes, liquid and polymer-gel, to demonstrate the applications in aqueous-based environments with different range of viscosities. The OSNTs device exhibits low power consumption/strain (~0.5 mW cm−2 %−1), large deformation (displacement ~7.88 mm; strain ~3.35%), fast response (speed ~1280 μm/s; time <1s), and excellent actuation stability (>96.5% after 25 hrs of continuous operation). These high-performance characteristics are ascribed to the enormous surface area of OSNTs associated with large ion exchange (mass flux ~167 g cm−3), low elastic modulus (average ~6.79 MPa), high charge storage density (charge density ~448 mC cm−2), and large specific capacitance (~170 F g−1) of OSNTs. Based on these remarkable features, we successfully constructed a miniaturized device consisting of multiple OSNTs-based microactuators that can be individually controlled at the same time. This study offers an available pathway to design high-performance electrochemical devices based on OSNTs for next-generation of micro and nano-scale actuators.

2. Results and Discussion

To fabricate the OSNTs device, we electrodeposited an electroactive layer of organic semiconductor polypyrrole doped with polystyrene sulfonate (PSS) around template poly-L-lactide (PLLA) nanofibers that were previously electrospun onto a thin layer of gold (Au) coated on a structural layer of flexible polypropylene (PP), followed by removal of PLLA nanofiber templates (Figure 1A-C). PSS, a large anionic dopant, was embedded into OS structure during electropolymerization to neutralize the positive charges of oxidized OS chains. Given that large counterions are immobile within the OS matrix, during redox reaction only cations/hydrated cations (here Na+) are exchanged between OS and electrolyte, resulting in significant enhancement of output strain and bending deformation of actuator in comparison with small counterions such as ClO4−.[15a] The average diameter of PLLA nanofibers and the resultant OSNTs (Figure 1D-E) were 140 ±4 nm and 626 ±16 nm, respectively (size distribution histograms are given in Figure S1, Supporting Information). As previously reported, PLLA is a biodegradable material with extremely slow degradation rate that can be processed into electrospun fibers, which remain stable during electrochemical deposition.[11a] Cross-sectional scanning electron micrographs of the OSNTs layer confirmed the presence of widespread pores and nanotubular structure of OS, which presumably facilitate charge storage with boosted ions transportation (Figure 1F-G). The OSNTs were subjected to cyclic voltammetry (CV) in aqueous solution and 0.2 wt.% agarose hydrogel both containing 0.1 M poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) (NaPSS) (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Low concentration gel polymer electrolytes with high ionic conductivity have been previously utilized for energy storage,[17] air working electrochemical actuators,[18] and biomedical applications.[19] Agarose hydrogel is optically transparent and allows for transportation of cations and/or solvated cations between the electrolyte and the actuator during CV cycling. The CV potential sweep was carried out within a range of −0.8 to +0.4 V at various scan rates of 10, 50, 100, and 200 mV s−1. CV was used to investigate the electroactivity of OSNTs actuator over a range of voltage and also conduct reversible electro-mechanical stimulation at various voltage scan rates.

Figure 1.

Fabrication and characterization of OSNTs device. (A) Schematic illustrates layered design of the actuator. (B) Step-by-step fabrication process of the OSNTs actuator: starting with a coverslip as carrier substrate covered with a removable double-sided tape on top (a), attachment of poly(propylene) (PP) film (30 μm thick) to the removable tape (b), sputtering of a thin layer of Au (~0.3 μm thick, Figure S4, Supporting Information) on the PP film (c), electrospinning of template PLLA nanofibers on the Au layer (d), electrodeposition of OS around electrospun PLLA nanofibers (~13 μm thick, Figure S4, Supporting Information) (e) removal of PLLA nanofibers to form OSNTs and finally detachment of the constructed actuator from the removable tape and the carrier substrate (f). (C) Photographs of gold-coated substrates after electrospinning of template PLLA nanofibers and electrodeposition of OS around template nanofibers followed by template removal to form OSNTs. (D) Scanning electron micrograph of the electrospun PLLA template nanofibers. (E) Scanning electron micrograph of the OSNTs. (F, G) Cross-sectional scanning electron micrographs of the OSNTs layer.

We investigated the bending displacement of the actuator under CV cycling in both liquid and gel electrolytes (Figure 2A-C). The actuator showed fully reversible bending deformation under consecutive reduction-oxidation (redox) reactions in each cycle (Movie S1 and S2, Supporting Information). The primary mechanism for bending deformation is the volume change of OSNTs due to the insertion and ejection of ions and solvent molecules into/out of the polymer matrix (Figure 2A). When ions and solvent enter the OSNTs, the polymer expands, and when they exit the OSNTs, the polymer contracts according to the following reaction:

| (1) |

, where n represents the number of electrons (e−), m represents the number of solvent molecules (S), OSNTsn+ is the oxidized state and OSNTs0 represents the neutral state. OSNTs0(PSS−)n indicates that anion PSS is entrapped into OSNTs as a dopant during electro-polymerization, and OSNTs0(PSS−)n (Na+)n (S)m indicates that Na+ cations and solvent molecules are inserted as the OSNTs is reduced.[20] According to Equation 1, when the OSNTs are reduced, cations (here Na+) and solvent molecules (here water) migrate from the electrolyte to the polymer to compensate the net charge and, resulting in swelling of the nanotubes. In contrast, when the OSNTs are oxidized, Na+ cations and water molecules migrate from the polymer to the electrolyte, leading to shrinkage of the nanotubes.[12b] The in-plane actuation strain generated upon reduction and oxidation of the OSNTs is converted into a bending deformation due to the strain mismatch between the active OSNTs and the passive underneath layers at the interface. Figure 2D-I depict the induced current, mass flux (influx/efflux), and tip displacement of the OSNTs actuator measured under a CV cycle at various scan rates of 10, 50, 100, and 200 mV s−1 in both liquid electrolyte (Figure 2D,F,H) and gel electrolyte (Figure 2E,G,I). During the initial forward scan (i.e. potential swept from 0 to −0.8 V), reduction of the OSNTs resulted in a steep increase in mass influx of cations into the OSNTs and in actuator displacement (counter-clockwise) (Figure S3, Supporting Information) as the potential swept to the cathodic peak potential, followed by a gradual increment in both mass flux and displacement curves. Interestingly, during the reverse scan (i.e. potential swept from −0.8 to +0.4 V), the mass flux and displacement further increased to their maximum values where the cathodic current reached zero at potentials −0.64, −0.61, −0.54, and −0.46 V in liquid electrolyte and −0.64, −0.59, −0.54, and −0.43 V in gel electrolyte at the scan rates of 10, 50, 100, and 200 mV s−1, respectively. As the anodic current increased (i.e. OSNTs were oxidized), both mass flux and displacement values gradually decreased due to the efflux of Na+ cations with clockwise deflection of the actuator. Subsequently, steep decreases were observed in the mass flux and displacement curves as the potential swept to the anodic peak potential. These decreases continued till all cations were expelled from OSNTs and actuator returned to its original position as depicted in inset Figure 2F-I. Furthermore, by increasing the potential, the mass flux slightly increased and the actuator deflected counter–clockwise (i.e. displacement increased) (Figure S3, Supporting Information) likely due to solvent transport into the OSNTs as an attempt to balance the osmotic pressure in the system.[21] As the scan rate decreased, the time-dependent diffusion of water molecules led to a more significant increase in the mass flux and the resulting displacement (insets in Figure 2F-I). Finally, during the second step of forward scan (i.e. potential swept from +0.4 V to 0 V), as OSNTs were still oxidized, the actuator mass flux and displacement remained unchanged or slightly decreased.

Figure 2.

Electrochemical actuation of OSNTs device using cyclic voltammetry. (A) Schematic represents ions transportation and the resulting bending movement in actuation of OSNTs upon redox processes. (B, C) Composite optical micrographs showing reversible bending deformation of the OSNTs actuator in liquid and gel electrolytes during cyclic voltammetry at the scan rate of 10 mV s−1 for one full cycle. Arrows show the direction of bending during consecutive reduction (R) and oxidization (O) processes. The OSNTs were deposited on the left-side of the actuator beam. (D-I) Cyclic voltammograms (D, E), mass flux (F, G), and tip displacement (H, I) of the OSNTs actuator as a function of potential during CV cycling in liquid and gel electrolytes containing 0.1 M NaPSS within the potential range of −0.8 to +0.4 V (versus Ag/AgCl) at various scan rates of 10 mV s−1 (blue square), 50 mV s−1 (green circle), 100 mV s−1 (red upward triangle), and 200 mV s−1 (black downward triangle). All plots correspond to the 10th cycle. Arrows indicate cycling direction.

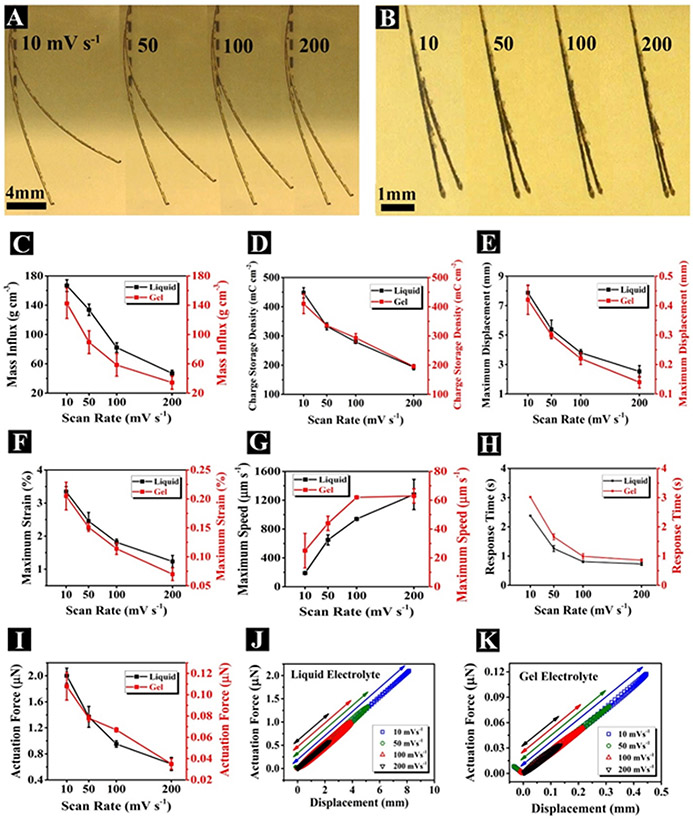

Next, we characterized the electro-chemo-mechanical response of the OSNTs device at various CV scan rates 10, 50, 100, and 200 mV s−1 in liquid and gel electrolytes (Figure 3). The device exhibited the largest mass flux (~167 g/cm3), charge storage density (~448 mC cm−2; Equation S1, Supporting Information), specific capacitance (~170 F g−1; Equation S2, Supporting Information), maximum displacement (~7.88 mm), and maximum strain (~3.35%; Equation S10, Supporting Information) at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 in liquid electrolyte. In fact, the high surface area to volume ratio along with high electrical conductivity and electrochemical activity of OSNTs provide smooth pathways for adequate ion transport and accumulation. To the best of our knowledge, the energy storage performance (i.e. charge storage density and specific capacitance) of our actuator exceeds those of reported OS based electrochemical actuators.[22] An increase in scan rate requires faster ion transport in the solvent and quicker intercalation and deintercalation of ions into/out of OSNTs respectively. However, due to restricted mobility of ions in an electrolyte under the influence of an electric field,[23] at higher scan rates fewer ions migrate into/out of polymer. Thus, the mass flux significantly declined (p <0.01) from 166.81 ±8.12 to 47.08 ±4.15 g cm−3 in the liquid electrolyte and from 142.38 ±20.54 to 34.38 ±9.27 g cm−3 in the gel electrolyte when scan rate was increased from 10 to 200 mV s−1 (Figure 3C). It is noteworthy that the charge storage density (Figure 3D) and specific capacitance (Figure S5) significantly decreased from 447.9 ±17 to 193.15 ±9.05 mC cm−2 and from 169.7 ±6.7 to 73.2 ±3.4 F g−1, respectively in the liquid electrolyte and from 410.15 ±33.95 to 195.45 ±6.25 mC cm−2 and from 155.4 ±12.9 to 74.0 ±2.4 F g−1, respectively in the gel electrolyte (p <0.01). In addition, there was no statistically significant difference between the charge storage density and specific capacitance of the actuator in liquid and gel electrolytes at same scan rates, suggesting that OSNT actuators maintain the same electroactivity in both gel and liquid electrolytes. In addition, the actuator generates a large maximum strain of 3.35% and a maximum displacement of 7.88 mm in liquid electrolyte at scan rate 10 mV s−1 (Figure 3E-F). Notably, maximum displacement (Figure 3E) and actuation strain (Figure 3F) decreased with increasing scan rate, presumably due to insufficient time for ion transport into/out of polymer at higher scan rates, as discussed earlier. The smaller displacement observed in the gel electrolyte compared to liquid can be attributed to the greater resistive forces exerted on the actuator by the surrounding viscoelastic gel, compared to aqueous solution.

Figure 3.

Electro-chemo-mechanical response of OSNTs device at various CV scan rates. (A, B) Composite photographs illustrate the maximum tip deflection occurs during CV cycling at different scan rates of 10, 50, 100, and 200 mV s−1 in liquid (A) and gel (B) electrolytes. (C-I) The OSNTs actuator response as a function of scan rate during cycling in liquid (black color) and gel (red color) electrolytes including: mass influx (C), charge storage density (D), maximum displacement (E), maximum strain (F), maximum speed (G), response time (H), and actuation force (I) (±SEM, n = 5). (J, K) The actuation force-displacement plots at various scan rates of 10 mV s−1 (blue square), 50 mV s−1 (green circle), 100 mV s−1 (red upward triangle), and 200 mV s−1 (black downward triangles) in liquid (J) and gel (K) electrolytes.

To investigate the electrochemical dynamics of the device, we assessed its speed, response time, and generated actuation force. The instantaneous velocity of the actuator tip was calculated from the rate of changes of the tip displacement (Figure S10, Supporting Information). As shown in Figure 3G, the maximum speed of actuator increased with increasing the scan rate. In liquid electrolyte, the actuator exhibited a high maximum speed of 190 ±10 μm s−1 at scan rate 10 mV s−1 and impressively a higher maximum speed of 1280 ±210 μm s−1 at scan rate 200 mV s−1. Notably, the actuator demonstrated faster response (<1s) at higher scan rates of 100 and 200 mV s−1 (Figure 3H), that are substantially improved compared with those observed in other OS-based electrochemical actuators (e.g. OS film with response time of 5s and maximum speed of ~1000 μm s−1).[24] In addition to offering a high maximum speed and a fast response time, this actuator was able to produce a large maximum force. It is worth nothing that the fast and large deformation is attributed to the extensive surface area of OSNTs, facilitating quick ion motion and accumulation.

The generated actuation force (Fact) was calculated by the moment equation of motion for a rigid body with variable mass that is submerged in a liquid. In fact, this equation relates the moment of forces acting on the actuator to angular momentum, (Figure S8, Figure S9, Equation S11-S19, Supporting Information).

| (2) |

, where m0 is initial mass of actuator (~1360 μg), Δm is mass change, ṁ = dm/dt is rate of mass change (Figure S10), δ is deflection, ν is velocity (Figure S10), α is acceleration (Figure S10), h is actuator thickness (~43.3 μm), b is actuator width (1 mm), l is actuator length (20 mm), Cd is drag coefficient (Equation S19, Supporting Information), ρ is electrolyte density (~1 g mm−3), and g is gravitational acceleration constant (9.81 m s−2). Prior modeling studies on bilayer CP actuators[12a, 25] operating in an electrolyte solution were based on the classical beam theory[26] for metal bimorphs that bend upon heating due to difference in thermal expansion coefficients (Timoshenko’s model),[27] whereas the normal force and bending moment at any cross section of the beam are zero. However, these models did not dynamically evaluate the actuator movement and did not consider the effect of fluid forces exerted on the actuator to determine the generated actuation force (i.e. blocking force). In contrast, our dynamic model, the moment equation of motion for a rigid body with variable mass that is submerged in a liquid, is more realistic and accurate as it considers the motion of the actuator under action of forces in a fluid. The actuator generated a force of 0.65 ±0.10 μN in liquid electrolyte at the scan rate 200 mV s−1. Impressively, the actuation force increased to 2.00 ±0.12 μN as the scan rate decreased to 10 mV s−1. Similarly, the generated actuation force had a substantial increase in gel electrolyte with decreasing the scan rate (Figure 3I, Figure S11, Supporting Information).

The correlation between the generated actuation force and the resultant deflection at various scan rates in liquid and gel electrolytes are plotted in Figure 3J-K. As shown, the actuator exhibited a reversible linear relation between actuation force (Fact) and deflection (δ) (Equation S20 and S21, Supporting Information). Interestingly, there was no significant difference between the slope of the plots in liquid and gel electrolytes at all scan rates (p >0.05) (for detailed calculations see Table S2 in Supporting Information). Furthermore, the deflection of OSNTs actuator was investigated according to Euler-Bernoulli’s composite beam theory.[27] Such a linear relationship for a cantilever beam can be described by a modified form of deflection equation as given in Equation 3.

| (3) |

, where γ is a constant, l is actuator length, and (EI)eff is the effective flexural rigidity of the composite beam that can be obtained using transformed sections method (Figures S6, Figure S7, Table S1, Equations S3-S9, see Supporting Information for detailed calculations). Using this approach, we obtained a value of γ ≈ 7.35 for the deflection equation, interestingly, in both liquid and gel electrolytes and statistical analysis revealed no significant difference (p >0.05) between γ values obtained from deflection at various CV scan rates in liquid and gel electrolytes (Table S2, Supporting Information).

Considering that the actuation strain in the electrochemical actuator depends on the electro-mechanical efficiency, the power consumption per generated strain is a particularly relevant metric to evaluate the actuation’s performance. Figure 4A illustrates the power consumption/strain of the OSNTs actuator at various CV scan rates in liquid and gel electrolytes. As shown, the power consumption/strain of the OSNTs actuator is within the ranges of 0.5 – 9.1 mW cm−2 %−1 in liquid electrolyte, and 9 – 159 mW cm−2 %−1 in gel electrolyte. The low power consumption/strain values for the OSNTs actuator operating in liquid electrolyte mark a profound improvement compared with previously reported electrochemical actuators operating in liquid[28] and air[4b, 29] (Figure 4A). To the best of our knowledge, there is no previous report on operation of electrochemical actuators in gel-polymer electrolytes. Notably, the OSNTs actuator yielded relatively low power consumption to strain in the gel electrolyte, which is comparable with air operating actuators and much less than those operating in liquid electrolyte. This superior performance presumably stems from enormous effective surface area of nanotubes that facilitates ion transport and accumulation as well as low elastic modulus of OSNTs that generates large strain, together resulting in low power consumption per strain. Such low power consumption/strain vastly raises their utility in various applications where power consumption/strain is desired to be minimal with maximal yield and actuation power.

Figure 4.

Long-term assessment of high performance OSNTs Device. (A) Power consumption/strain percentage of the OSNTs actuator, compared with different types of soft electrochemical actuators. (B) Bending stability (δ/ δ0) of the OSNTs actuator over 15000 actuations at 200 mV s−1 (25 hours of continuous operation). δ0 corresponds to the actuator deflection at the first cycle, and δ is the deflection at the nth cycle. Inset represents the sample variation in the maximum tip deflection (δmax) within the first 1000 actuations in liquid and gel electrolytes (±SEM, n = 3). There is no significant difference in the δmax over the course of actuation in both liquid and gel electrolytes (p >0.05). (C, D) Scanning electron micrographs of OSNTs before (C) and after (D) actuation at scan rate of 200 mV s−1 for 1000 times. (E, F) Optical microphotographs of the transverse cross-section of the actuator after actuation for 1000 times at scan rate of 200 mV s−1.

Further, we evaluated the long-term stability (i.e. mechanical durability) of the OSNTs device over a great number of actuations (Figure 4B). Remarkably, the OSNTs device showed a bending stability >96.5% in liquid electrolyte over 15,000 actuations (25 hours of continuous operation) at scan rate 200 mV s−1 (equivalent to cycling frequency 0.08 Hz). While electron micrographs (Figure 4C-D) and optical micrographs (Figure 4E-F) did not indicate any obvious mechanical damage or delamination of OSNTs over the course of actuation, the slight degradation in actuator displacement (~3.5%) may be attributed to the nanoscale deformation and stress relaxation in OSNTs. These results suggest that the OSNTs actuator can effectively operate in liquid and gel electrolytes and can mechanically endure a large number of actuations. In fact, this OSNTs actuator exhibited superior long-term stability compared with previously reported CP-based actuators operating in liquid electrolyte (e.g. CP film[30] with substantial bending degradation after 11 hr).[30-31]

To demonstrate the potential applications based on the large actuation deformation, as a proof of concept we focused on development of a movable microprobe based on OSNTs microactuators. The shape and geometry of the microprobe is similar to implantable Michigan neural electrodes.[13e, 32] Using standard layer-by-layer photolithography processes, we microfabricated a miniaturized device consisting of three gold-coated cantilevers (500 μm x 50 μm, marked as “P”), six gold circular electrode sites (30 μm diameter, marked “Q”), and nine squared contact pads (150 μm x 150 μm, marked “R”) on a 13 μm polymer substrate (Figure 5A-B). Each cantilever and electrode site has a separate circuit and is connected to an individual contact pad by 20 μm wide gold traces. Finally, the miniaturized device was assembled on a printed circuit board and wire-bonded to the board through the contact pads (Figure 5C). As shown in Figure 5D-E, the OSNTs were coated on the microcantilevers (P) and were subjected to CV potential sweeps (within a range of −0.8 to +0.4 V at various scan rates of 50 to 200 mV s−1). The displacement of each microcantilever was separately controlled by adjusting the scan rate (e.g. a displacement of ~80 μm was obtained at scan rate 200 mVs−1, Figure 5D). To assess the effect of microcantilevers deflection on electrical performance of the movable electrode sites (Q) located on the tip of microcantilevers, the impedance of the electrodes was measured before and after actuation and was compared with that of the fixed reference electrodes. Notably, the impedance of the bare gold electrode sites remained the same as before actuation (~190 kΩ at 1 kHz, Figure S12 in Supporting Information). This microprobe can be potentially implanted in the brain and neural signal recordings which are adversely affected by reactive tissue responses and/or displacement of the neurons[33] may be enhanced by adjusting the position of recording sites (Q) located on the movable microcantilevers (P).

Figure 5.

A proof of concept for utilization of OSNTs device for movable neural microprobes. (A, B) Optical micrographs of the probe with three microcantilevers fabricated using standard photolithography. The probe consisting of three gold-coated microcantilevers (marked by P), six circular electrode sites (marked by Q), and nine connection pads (marked by R). (C) A photograph of the microprobe assembled on a printed board circuit using wire-bonding. (D) Actuation of microcantilevers coated with OSNTs under CV at 200 V s−1. Each microcantilever can be individually controlled for a desired range of motion. (E) Scanning electron micrograph of the probe microcantilever coated with OSNTs.

3. Conclusions

In summary, this study presents a new and versatile method for design and development of electrochemical device, with OSNTs as the main constituent, capable of operating in liquid and gel polymer electrolytes. The device exhibits excellent electrochemical characteristics including, low power consumption/strain, large deformation, fast ion transport/accumulation, tunable dynamics, and excellent actuation stability. This high performance is attributed to the enormous surface area of OSNTs associated with large ion exchange and accumulation, low elastic modulus, high charge storage density, and large specific capacitance. By exploiting these impressive features, we designed and fabricated a miniaturized movable device consisting of multiple OSNTs-based microactuators that can be individually controlled at the same time. The experimental studies of motion and mass transport along with theoretical analysis of a body system with variable mass were utilized to establish the dynamics of the actuator and to introduce a modified form of Euler-Bernoulli’s deflection equation for the OSNTs actuator. Various types of chemically derived and functionalized organic semiconductors can be formulated to further enhance electro-chemical-mechanical properties of this device, exceeding the electrochemical performance. Considering these achievements along with versatile application of OSNTs and OSNFs,[11a, 13d, 13e, 16] we anticipate that the OSNTs- based electrochemical device will be utilized for advancement of next generation actuators in the fields of soft robotics, artificial muscles, bioelectronics, and biomedical devices.

4. Experimental Section

Materials:

Poly(L-lactide) (PLLA, Resomer 210) with the inherent viscosity of 3.3-4.3 dL g−1 was purchased from Evonik Industries. Benzyl triethylammonium chloride and pyrrole (Py) (Mw = 67.09 g mol−1) were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Poly(sodium-p-styrene sulfonate) (NaPSS, Mw = 70 kD) and chloroform were purchased from Acros-Organics. Agarose powder (Agarose I™, Gel strength ≥ 1200 g cm−1) was purchased from VWR Life Science. 6 MHz Au/TiO2 quartz crystal wrap-around electrodes were purchased from Metrohm, USA. Biaxially-oriented poly(propylene) (PP) films were obtained from backing layer of Scotch removable double-sided tape (3M™).

Fabrication of Nanoscale Fiber Templates:

A homogeneous solution of PLLA (3 wt.%) in chloroform was prepared by adding 230 mg PLLA in 5 ml chloroform and stirring the mixture overnight at room temperature. To enhance the solution charge strength, 23 mg Benzyl triethylammonium chloride (an organic salt) was added to the solution prior to stirring. PLLA nanofibers were directly electrospun onto Au-coated substrates using a syringe pump with the spinneret gauge of 23. The electrospinning process was carried out in an electric field of 0.91 kV cm−1 with a flow rate of 50 μL hr−1, and a syringe-substrate distance of 11 cm for 6 min. Temperature and humidity were kept constant at 26°C and 30%, respectively. For the bilayer beam actuator, the passive layer was a PP film (30 μm thick, 1 mm wide, and 20 mm long) coated with a thin gold layer (~0.3 μm, Figure S4) using a desktop sputtering system (Denton Desk II) at 40 mA for 8 min. For electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance (EQCM) measurements, PLLA nanofibers were electrospun on Au-coated quartz crystals (diameter ~6.7 mm) for 1 min using the same process parameters.

Electrochemical Deposition of Organic semiconductor:

0.2 M electrolyte solution was prepared by dissolving 277 μL Py monomer and 824 mg NaPSS in 20 ml deionized water. Prior to electrodeposition, samples were kept in the electrolyte solution for 30 min to ensure that the solution has completely diffused into the fiber interspaces. Then, the electrodeposition was carried out at the current density of 0.5 mA cm−2 for 2 hrs. To fabricate OSNTs, PPy was electropolymerized around template PLLA nanofibers, and then the template PLLA was dissolved in chloroform to create OSNTs. The Electrochemical deposition was performed using an Autolab PGSTAT 128N (Metrohm, USA) in galvanostatic mode with a two-electrode configuration at room temperature. For EQCM samples, electrodeposition was performed for 15 min using an Autolab EQCM kit in which a gold wire served as the counter electrode. For bilayer beam actuator, samples were connected to the working electrode and a platinum (Pt) foil served as the counter electrode.

Microfabrication of Probes using Layer-by-Layer Photolithography:

The probe fabrication was performed on a silicon wafer substrate with a thermal oxide layer (SiO2, 2 μm thick) as a sacrificial layer for final device release. The probe device was developed by three SU-8 layers (structural material) and two thin layers of Cr/Au (for electrical pads, traces and electrode sites). First, a SU-8 layer (~8 μm thick) was spun coated onto the substrate (at 1000 rpm for 30 s) and soft baked at 105°C for 15 min. To shape the probe with three embedded microcanteilver, the SU-8 layer was UV exposed at 12.5 mj/cm2 for 16 s under a patterned glass photomask and was post-baked at 95°C for 3 min. The exposed SU-8 layer was developed by immersion in SU-8 developer for 3 min. Second, three circular sites of Cr/Au along with their connection traces and pads were deposited through e-beam evaporation on the first SU-8 layer (Cr film thickness = 10 nm, Au film thickness = 100 nm). The electrode sites were patterned by a positive liftoff resist prior to Cr/Au deposition. After Cr/Au deposition, the liftoff resist was removed through bath sonication in acetone. Third, another layer of SU-8 (~5 μm thick) was developed on the entire probe except the electrode sites and the pads (the connection traces were insulated by the SU-8 layer). All processing parameters (i.e. spin coating, baking, and development) were the same as the first SU-8 layer except the spin coating speed that was set at 3000 rpm. Forth, the second layer of Cr/Au (including cantilever projections and circular reference electrodes sites on the probe frame with their connection traces and pads) was deposited using a patterned lift-off resist. Fifth, the last layer of SU-8 (~5 μm thick) was developed on the entire probe except the projections, electrode sites, and the connection traces and pads. Ultimately, the final device was stripped off the substrate by dissolution of the sacrificial SiO2 layer in HF solution (30%). The probes were annealed at 150 °C to relieve the residual stresses in the SU-8 layers.

Beam Actuation using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV):

Actuation of the bilayer beam actuator was performed using Autolab PGSTAT 128 in a three-electrode configuration with a saturated Ag/AgCl reference electrode and a 1 cm × 2 cm Pt foil as counter electrode (Figure S2). The CV was performed within the potential range of −0.8 to +0.4 V at various scan rates of 10, 50, 100, and 200 mV s−1. The actuation behavior of the constructed bilayer beam was assessed in aqueous and agarose hydrogel (0.2 wt.%) electrolytes containing 0.1 M NaPSS. To prepare the aqueous electrolyte, 824 mg NaPSS was dissolved in 40 ml de-ionized water at room temperature. For gel preparation, 80 mg agarose powder was added into 40 ml NaPSS solution (0.1 M), and the slurry was heated in a microwave oven for 1 min to dissolve agarose in the NaPSS solution. The agarose solution was then cooled down in refrigerator at 4 °C for 15 min. Prior to actuation, all samples were primed in the NaPSS solution at the scan rate of 100 mV s−1 for 10 cycles.

Electrochemical Quartz Crystal Microbalance (EQCM) Measurements:

The EQCM measurement was carried out using Autolab PGSTAT 128N equipped with EQCM kit in a three-electrode configuration with a saturated Ag/AgCl reference electrode and a gold counter electrode. The mass measurements of OSNTs under CV was characterized in the liquid and gel electrolytes containing 0.1 M NaPSS. The OSNTs were cycled in the potential range of −0.8 to +0.4 V (versus the Ag/AgCl reference electrode) for 20 cycles, at different scan rates of 10, 50, 100, and 200 mV s−1 at room temperature. Prior to the measurements, a stable ion concentration within the OS structure was ensured by subjecting the samples to 5 CV cycles at the scan rate of 10 mV s−1. The mass change was calculated using Sauerbrey’s equation which correlates the frequency variation (Δf) in quartz crystal oscillation to the change in mass (Δm):

| (4) |

, where Cf is a sensitivity factor that depends on the resonant frequency and operating temperature of the quartz crystal. The value of Cf was 0.0815 Hz ng−1 cm−1 for this 6 MHz quartz crystal at 20 °C. Compared to the actuator, a thinner layer of OSNTs (1.44 μm) was used for EQCM measurements to avoid viscoelastic effects. The mass change of the actuator was estimated by multiplying the EQCM values by the volume ratio of OS layer on the actuator and the EQCM sample (Volume ratio ≅ 5).

Actuator Tip Kinematic Measurements:

The bending deflection of the actuator was recorded using a digital camera (Dino-Lite) with 30 frames per second. The recorded videos were then processed using an open-source software (Tracker 5.0.6, https://physlets.org/tracker) to track the actuator tip deflection upon actuation. The response time (tR) at the maximum tip deflections was calculated by subtraction of the time that actuator positioned at the maximum deflection from the time that stimulus cathodic current reached zero.

Mechanical Characterization of the Actuator:

Elastic modulus of the actuator components (i.e. OS film, Au layer, and OSNTs in both reduced and oxidized states) were obtained by atomic force microscopy (AFM) in fluid in either contact mode and/or peak force mode as appropriate and indicated below. Force-indentation curves were obtained on a Bruker BioScope Resolve (Bruker nanoSurfaces, CA) AFM employing a ScanAssyst-Fluid+ cantilever (Bruker NanoSurfaces, CA) with a pyramidal tip (qualified tip radius ~ 3.26 nm), nominal spring constant of 0.7 N m−1 assuming sample Poisson’s ratio as 0.5. Prior to experimental samples, cantilever was calibrated on a silicon wafer in fluid. Force curves were obtained in contact mode (n = 7 to 10 locations, 4 force curves per location) and analyzed using the Sneddon model. Elastic moduli were estimated using a custom MATLAB code.

Rheological Characterization of Liquid and gel electrolytes:

The viscosity of 0.1 M NaPSS solution and 0.2 wt.% agarose gel containing 0.1 M NaPSS was characterized using an AR2000ex rheometer (TA instruments) at room temperature. Viscosity measurement was carried out within the shear rate of 10−3 – 10 s−1 using a 40 mm parallel plate with a gap of 0.5 mm.

Structural Characterization of the Actuator:

The surface morphology of PLLA nanofibers and OSNTs were characterized using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM, FEI 235). Samples were mounted on aluminum stubs by carbon tape and a carbon paint was used for grounding. Prior to microscopy, non-conducive PLLA sample was sputter-coated with a thin gold layer using Denton Sputter Coater for 45 s at 40 mA. Thickness of actuator layers including gold and OSNTs were measured using materials confocal microscopy (LSM800 Zeiss, Germany). For higher precision, the gold and OSNTs were constructed on a polished Si wafer using the same processing parameters. Thickness profiles and 3D surface topography of OSNTs layer (Figure S4, Supporting Information) were generated through a z-stack experiment followed by step height analysis using Confomap software (Zeiss, Germany).

Statistical Analysis:

The statistical significance of difference of data was performed by one-way ANOVA and post hoc test (Tukey's test) to analyze significances between sample groups (Origin Pro, Northampton, MA). In this paper, all data are presented as mean ± standard error, unless otherwise noted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by US National Institute of Health Grant R01 NS087224 and National Science Foundation CAREER Award DMR 1753328.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Mohammadjavad Eslamian, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Houston, 3517 Cullen Blvd, Houston, TX 77204, USA.

Fereshtehsadat Mirab, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Houston, 3517 Cullen Blvd, Houston, TX 77204, USA.

Vijay Krishna Raghunathan, Department of Basic Sciences, The Ocular Surface Institute, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Houston, Houston, TX, 77204, USA.

Sheereen Majd, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Houston, 3517 Cullen Blvd, Houston, TX 77204, USA.

Mohammad Reza Abidian, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Houston, 3517 Cullen Blvd, Houston, TX 77204, USA.

References

- [1].Paulino C, Kalienkova V, Lam AK, Neldner Y, Dutzler R, Nature 2017, 552, 421–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Mirvakili SM, Hunter IW, Adv. Mater 2018, 30, 1704407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bar-Cohen Y, Electroactive polymer (EAP) actuators as artificial muscles: reality, potential, and challenges, Vol. 136, SPIE press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Ghilardi M, Boys H, Török P, Busfield JJ, Carpi F, Sci. Rep 2019, 9, 1–10; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Carpi F, Kornbluh R, Sommer-Larsen P, Alici G, Bioinspir. Biomim 2011, 6, 045006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhao Y, Song L, Zhang Z, Qu L, Energy Environ. Sci 2013, 6, 3520–3536; [Google Scholar]; d) Carpi F, Smela E, Biomedical applications of electroactive polymer actuators, John Wiley & Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Yan Y, Santaniello T, Bettini LG, Minnai C, Bellacicca A, Porotti R, Denti I, Faraone G, Merlini M, Lenardi C, Adv. Mater 2017, 29, 1606109; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lu L, Liu J, Hu Y, Zhang Y, Chen W, Adv. Mater 2013, 25, 1270–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Takeuchi I, Asaka K, Kiyohara K, Sugino T, Terasawa N, Mukai K, Fukushima T, Aida T, Electrochim. Acta 2009, 54, 1762–1768. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kim J, Jeon J-H, Kim H-J, Lim H, Oh I-K, Acs Nano 2014, 8, 2986–2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lu C, Yang Y, Wang J, Fu R, Zhao X, Zhao L, Ming Y, Hu Y, Lin H, Tao X, Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kong L, Chen W, Adv. Mater 2014, 26, 1025–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kaneto K, Kaneko M, Min Y, MacDiarmid AG, Synth. Met 1995, 71, 2211–2212. [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Dingler C, Müller H, Wieland M, Fauser D, Steeb H, Ludwigs S, Adv. Mater 2021, 33, 2007982; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gladisch J, Stavrinidou E, Ghosh S, Giovannitti A, Moser M, Zozoulenko I, McCulloch I, Berggren M, Adv. Sci 2020, 7, 1901144; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hamedi MM, Campbell VE, Rothemund P, Güder F, Christodouleas DC, Bloch JF, Whitesides GM, Adv. Funct. Mater 2016, 26, 2446–2453; [Google Scholar]; d) Bay L, West K, Sommer-Larsen P, Skaarup S, Benslimane M, Adv. Mater 2003, 15, 310–313. [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Abidian MR, Kim DH, Martin DC, Adv. Mater 2006, 18, 405–409; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Smela E, Adv. Mater 2003, 15, 481–494; [Google Scholar]; c) Hamedi M, Forchheimer R, Inganäs O, Nat. Mater 2007, 6, 357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Pei Q, Inganaes O, J. Phys. Chem 1992, 96, 10507–10514; [Google Scholar]; b) Bay L, Jacobsen T, Skaarup S, West K, J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 8492–8497. [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Wadhwa R, Lagenaur CF, Cui XT, J. Controlled Release 2006, 110, 531–541; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Berggren M, Richter-Dahlfors A, Adv. Mater 2007, 19, 3201–3213; [Google Scholar]; c) Rivnay J, Inal S, Salleo A, Owens RM, Berggren M, Malliaras GG, Nat. Rev. Mater 2018, 3, 1–14; [Google Scholar]; d) Abidian MR, Corey JM, Kipke DR, Martin DC, small 2010, 6, 421–429; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Abidian MR, Ludwig KA, Marzullo TC, Martin DC, Kipke DR, Adv. Mater 2009, 21, 3764–3770; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Fahlman M, Fabiano S, Gueskine V, Simon D, Berggren M, Crispin X, Nat. Rev. Mater 2019, 4, 627–650. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Temmer R, Must I, Kaasik F, Aabloo A, Tamm T, Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2012, 166, 411–418. [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Yan B, Wu Y, Guo L, Polymers 2017, 9, 446; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hu F, Xue Y, Xu J, Lu B, Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2019, 6, 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yang G, Kampstra KL, Abidian MR, Adv. Mater 2014, 26, 4954–4960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].a) Kim CS, Oh SM, J. Power Sources 2002, 109, 98–104; [Google Scholar]; b) Liang S, Yan W, Wu X, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Wang H, Wu Y, Solid State Ionics 2018, 318, 2–18. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lee S-K, Choi Y, Sim W, Yang SS, An H, Pak JJ, in Smart Structures and Materials 2000: Electroactive Polymer Actuators and Devices (EAPAD), Vol. 3987, International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2000, pp. 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- [19].a) Pomfret R, Miranpuri G, Sillay K, Annals of neurosciences 2013, 20, 118; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Parupudi T, Rahimi R, Ammirati M, Sundararajan R, Garner AL, Ziaie B, Electrophoresis 2018, 39, 2262–2269; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Sillay K, Schomberg D, Hinchman A, Kumbier L, Ross C, Kubota K, Brodsky E, Miranpuri G, J. Neural Eng 2012, 9, 026009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Smela E, MRS Bull. 2011, 33, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- [21].a) Stavrinidou E, Leleux P, Rajaona H, Khodagholy D, Rivnay J, Lindau M, Sanaur S, Malliaras GG, Adv. Mater 2013, 25, 4488–4493; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Eslamian M, Antensteiner M, Abidian MR, in 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), IEEE, 2018, pp. 4472–4475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Wang D, Lu C, Zhao J, Han S, Wu M, Chen W, RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 31264–31271; [Google Scholar]; b) Terasawa N, Asaka K, Langmuir 2016, 32, 7210–7218; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Li Y, Tanigawa R, Okuzaki H, Smart Mater. Struct 2014, 23, 074010; [Google Scholar]; d) Okuzaki H, Takagi S, Hishiki F, Tanigawa R, Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2014, 194, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Péraud J-P, Nonaka AJ, Bell JB, Donev A, Garcia AL, PNAS 2017, 114, 10829–10833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Della Santa A, De Rossi D, Mazzoldi A, Synth. Met 1997, 90, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- [25].a) Christophersen M, Shapiro B, Smela E, Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2006, 115, 596–609; [Google Scholar]; b) Shapiro B, Smela E, J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct 2007, 18, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gere JM, Timoshenko SP, Comp., Boston: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Timoshenko S, Josa 1925, 11, 233–255. [Google Scholar]

- [28].a) Sansiñena JM, Gao J, Wang HL, Adv. Funct. Mater 2003, 13, 703–709; [Google Scholar]; b) Panwar V, Jeon J-H, Anoop G, Lee HJ, Oh I-K, Jo JY, J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 19718–19727; [Google Scholar]; c) Ding J, Zhou D, Spinks G, Wallace G, Forsyth S, Forsyth M, MacFarlane D, Chem. Mater 2003, 15, 2392–2398; [Google Scholar]; d) Kiefer R, Martinez JG, Kesküla A, Anbarjafari G, Aabloo A, Otero TF, Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2016, 233, 328–336. [Google Scholar]

- [29].a) Wu G, Wu X, Xu Y, Cheng H, Meng J, Yu Q, Shi X, Zhang K, Chen W, Chen S, Adv. Mater 2019, 31, 1806492; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kim O, Kim H, Choi UH, Park MJ, Nat. Commun 2016, 7, 1–8; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Li J, Ma W, Song L, Niu Z, Cai L, Zeng Q, Zhang X, Dong H, Zhao D, Zhou W, Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 4636–4641; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Terasawa N, Ono N, Mukai K, Koga T, Higashi N, Asaka K, Carbon 2012, 50, 311–320; [Google Scholar]; e) Mukai K, Asaka K, Sugino T, Kiyohara K, Takeuchi I, Terasawa N, Futaba DN, Hata K, Fukushima T, Aida T, Adv. Mater 2009, 21, 1582–1585; [Google Scholar]; f) Lu L, Liu J, Hu Y, Zhang Y, Randriamahazaka H, Chen W, Adv. Mater 2012, 24, 4317–4321; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Lee J-W, Yoo Y-T, Lee JY, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 1266–1271; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Wu G, Hu Y, Zhao J, Lan T, Wang D, Liu Y, Chen W, Small 2016, 12, 4986–4992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Idla K, Inganäs O, Strandberg M, Electrochim. Acta 2000, 45, 2121–2130. [Google Scholar]

- [31].a) Kim B, Too C, Kwon J, Ko J, Wallace G, Synth. Met 2011, 161, 1130–1132; [Google Scholar]; b) Lu W, Fadeev AG, Qi B, Smela E, Mattes BR, Ding J, Spinks GM, Mazurkiewicz J, Zhou D, Wallace GG, Science 2002, 297, 983–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rousche PJ, Pellinen DS, Pivin DP, Williams JC, Vetter RJ, Kipke DR, IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng 2001, 48, 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Polikov VS, Tresco PA, Reichert WM, J. Neurosci. Methods 2005, 148, 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.