Abstract

Introduction:

Physician decision-making surrounding choices for large joint and bursa injections is poorly defined, yet influence patient safety and treatment effectiveness.

Objective:

The present study aimed to identify practice patterns and rationale related to injectate choices for large joint and bursal injections performed by physician members of the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM).

Design:

An electronic survey was sent to 3,400 members of the AMSSM. Demographic variables were collected: primary specialty (residency), training location, practice location, years of clinical experience, current practice type, and rationale for choosing an injectate.

Participants:

A total of 674 physicians responded (minimum response rate of 20%).

Intervention:

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measures:

Outcomes of interest included corticosteroid type and dose, local anesthetic type, and total injectate volume for each large joint or bursa (hip, knee, and shoulder).

Results:

Most respondents used triamcinolone (50-56% of physicians, depending on injection location) or methylprednisolone (25-29% of physicians), 21-40mg (53-60% of physicians), diluted with lidocaine (79-87%) for all large joint or bursa injections. It was noted that 36.2% (244/674) of respondents reported using >40mg for at least one injection type. Most (90.5%, 610/674) reported using an anesthetic other than ropivacaine for at least one type of joint or bursa injection. Physicians who reported lidocaine use were less likely to report that their injectate choice was based on literature that they reviewed (OR = 0.41 [0.27-0.62], p <0.001). Respondents predominantly used 5-7mL of total injectate for all large joints or bursae (45-54% of respondents), except for the pes anserine bursa, where 3-4mL was more common (51% of physicians).

Conclusions:

It appears that triamcinolone and methylprednisolone are the most commonly-used corticosteroids for sports medicine physicians; most physicians use 21-40mg of corticosteroid for all injections, and lidocaine is the most-often used local anesthetic; very few use ropivacaine. Over a third of respondents used high-dose (>40mg triamcinolone or methylprednisolone) for at least one joint or bursa.

Keywords: cortisone, lidocaine, bupivacaine, ropivacaine, triamcinolone, methylprednisolone, betamethasone, dexamethasone, steroid

Introduction:

Corticosteroid injections are a commonly-performed procedure in musculoskeletal medicine, particularly for large joints and bursae (shoulder, hip, and knee). Surprisingly, despite their use since the 1950s,1,2 there is no consensus on ideal doses and corticosteroid type. Studies have examined ideal doses, with mixed findings.3,4 Furthermore, it is common to mix a local anesthetic with the corticosteroid to provide temporary pain relief and diagnostic value.5,6 As no specific guidelines are available, musculoskeletal practitioners may use different corticosteroid/local anesthetic mixtures for the same conditions.

A small body of literature has examined practice patterns amongst physicians for these injections.4,7-10 These studies have identified practice differences between corticosteroid dosages used,10 corticosteroid type used, 4,10 volumes used,10 local anesthetics used, 10 training locations,7 rationale for choosing a particular corticosteroid,7,10 residency training,4 and frequency of injections9. Physicians commonly deny using a specific rationale for their injection practices.10 In prior studies, the most commonly-reported corticosteroids used are triamcinolone, methylprednisolone, and betamethasone.4,10 Though prior studies have examined large joint injections among sports medicine physicians4,9, generalizability of these results are limited by small regional samples. Additionally, given the ever-evolving healthcare landscape, current practice patterns have likely changed since the time of these publications (2005-2007). Finally, numerous studies have demonstrated detrimental effects associated with corticosteroid administration11-15. While no specific guidelines exist, it is generally agreed that judicious administration of the minimal amount of corticosteroid to produce a clinically significant effect is important. Similarly, local anesthetic choices are relevant to potential toxicity to chondrocytes and tenocytes16-18; of note, bursal injections around large joints – subacromial, greater trochanter, pes anserine – all are peritendinous injections.

This study aimed to identify practice patterns and rationale relevant to injectate choices for large joint and bursal injections performed by physician members of the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM). Specifically, physicians were queried regarding: 1) types/dosages of corticosteroid used, 2) types of local anesthetics used, 3) volumes of injectate used, and 4) rationale for injectates used. Additionally, we sought to identify demographic and geographic factors associate with injectate choices.

Methods:

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained through the University of Utah for this cross-sectional survey study. The investigators disseminated an electronic survey to approximately 3,400 AMSSM physician members via email, with two follow-up reminders spaced at two-week intervals. The AMSSM research committee reviewed the survey and approved it prior to dissemination. The survey included questions regarding physician demographics, as well as usage of corticosteroids and local anesthetics, specifically for large joint and bursal injections (see appendix). Anonymous responses were collected via REDCap19 with only fully-completed surveys included. The following demographic variables were collected: primary specialty (residency), training location, practice location, years in practice, and current practice type. Outcomes of interest included corticosteroid type and dose, local anesthetic type, and total injectate volume for each large joint or bursa injection. Specifically, injection practices related to the hip (intra-articular and greater trochanteric bursa), knee (intra-articular and pes-anserine bursa), and shoulder (glenohumeral joint intra-articular and subacromial bursa) were evaluated. The rationale for practice choices was also queried.

Frequencies and percentages were calculated for the demographic data, and an analysis of outliers was performed. As prior literature has demonstrated commonly-reported dosages for large joint and bursa injections ranging from 20 to 80mg of methylprednisolone or triamcinolone equivalents,3 outliers were identified above 80mg or below 20mg. “Lower” doses were identified as 0-40mg, while “higher” doses were categorized as being greater than 40mg, based on rationales used in other studies.3,20 Because triamcinolone and methylprednisolone were the most often used corticosteroids, betamethasone and dexamethasone were removed from some analyses relating to dosages. Little literature exists on “low” or “high” volumes of injectate (anesthetic/saline plus corticosteroid) for a large joint,21 so values that fell out of the total interquartile ranges were a priori deemed to fit their respective categories (e.g. “low” would refer to volume categories that were less than the 25th percentile of total practice patterns, while “high” would be those above the 75th percentile). In order to identify factors associated with the practice patterns identified by survey responses, binomial logistic regression was used for the categorical dependent variables. The following variables were categorized in the following manner: primary use of a type of corticosteroid (use of this corticosteroid in the majority of their injections), primary use of a type of anesthetic (use of this anesthetic in the majority of their injections), use of the same corticosteroid in all joints, use of the same anesthetic in all joints, use of low volume in a large joint (<3mL in any joint), or use of high volume in a large joint (>7mL in any joint). The independent variable list contained: primary specialty (baseline “other specialty”), years in practice (baseline >30 years), practice geographic region (baseline International), training region (baseline International), injectate rationales (yes/no for each question), and practice setting (academic vs non-academic). Statistical analysis was performed with PSPP 1.2.0 software (GNU Project, Boston, MA), with p values of less than 0.05 considered significant.

Results:

Of the 3,400 members of the AMSSM to whom the survey was sent, 674 responded (rate of 20%). It is very likely that the true response rate is higher than 20%, as it is unknown how many emails in the listserv are active and how many members viewed the email. Table 1 displays the demographic information of the respondents.

Table 1 -.

Survey respondents, N = 674. PM&R = Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation.

| Training location | Midwest (31%) |

| South (28%) | |

| West (20%) | |

| Northeast (19%) | |

| Outside of US (1%) | |

| Practice setting | Academic (37%) |

| Non-academic (63%) | |

| Specialty | Family medicine (72%) |

| PM&R (10%) | |

| Internal medicine (6.7%) | |

| Pediatrics (5.4%) | |

| Other (5.5%) | |

| Years in practice since training | 1-5 years (32%) |

| 11-20 years (21%) | |

| 6-10 years (20%) | |

| In training (13%) | |

| Greater than 20 years (13%) |

Corticosteroid use

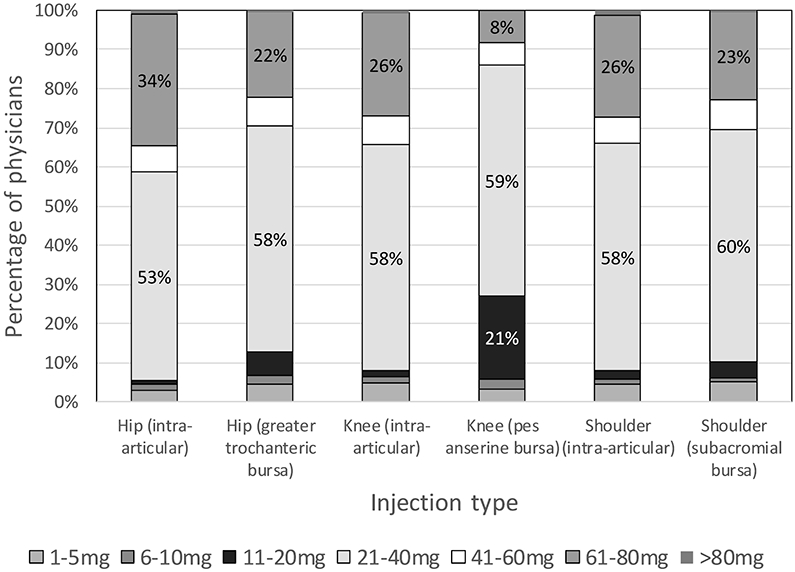

Triamcinolone (50-56% of physicians, depending on joint/bursa injection) and methylprednisolone (25-29% of physicians, depending on joint/bursa injection) were the most commonly-used corticosteroids (Figure 1) for all large joint and bursal injections. Of all physicians using triamcinolone, 81% (321/395) used it for all injections. Similarly, of those using methylprednisolone, 77% (144/187) used it for all injections. Of note, 6.8% (46/674) of physicians reporting using dexamethasone for a joint/bursa injection. The most common reasons for corticosteroid/local anesthetic choice was information gained during fellowship training (75% of physicians, 504/674), clinical experience (62%, 415/674), and literature review (41%, 277/674). No demographic or geographic factors were related to use of dexamethasone in any joint or bursa. Similarly, for respondents who primarily use triamcinolone or methylprednisolone, choice of corticosteroid was also not related to any factor in the logistic regression model (Table 2). However, those who reported basing their decision on what they learned from a colleague after training were less likely to use the same corticosteroid type for all joints (OR = 0.46 [0.28-0.75], p = 0.002). Figure 2 displays the corticosteroid dose preferences for physicians, examining the two most common corticosteroids used, methylprednisolone and triamcinolone, which have equivalent potency. Excluding the pes anserine bursa, 22-34% of physicians used 61-80mg, while 53-60% used 21-40mg, depending on the structure. The pes anserine bursa showed over half (59%) of respondents using 21-40mg, but 21% using 11-20mg. The proportion of physicians who reported using greater than 40mg per injection ranged from 12.6% (pes anserine) to 39.7% (hip), with 36.2% reporting using this high dose for at least one joint or bursa (if the hip joint is excluded, 33.8% used the high dose for at least one).

Figure 1 -.

Types of corticosteroid used in large joint/bursal injections. The vertical axis represents the percentage of physicians who primarily use each type of corticosteroid for each injection type. N values for each joint/bursa were as follows: hip (n = 401), greater trochanteric bursa (n = 575), knee (n = 648), pes anserine bursa (n = 382), glenohumeral (n = 525), subacromial (n = 641).

Table 2 –

Significant associations identified with logistic regression models. Potential independent variables included: primary specialty, years in practice, practice geographic region, training region, injectate rationale, and practice setting (academic vs non-academic).

| Dependent variable | Significantly associated with |

Pos/Neg association |

Odds ratio (95% confidence intervals), p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroid use | |||

| Use of triamcinolone or methylprednisolone primarily | None | N/A | N/A |

| Use of dexamethasone | None | N/A | N/A |

| Use same corticosteroid type for all joints | Choice based on what they learned from colleagues after training | Less likely | 0.46 (0.28-0.75), p = 0.002 |

| Local anesthetic use | |||

| Use lidocaine for all joints/bursae | Choice based on what they learned in fellowship training | More likely | 1.85 (1.13-3.02), p = 0.014 |

| Choice based on literature they had reviewed | Less likely | 0.41 (0.27-0.62), p < 0.001 | |

| Use ropivacaine in at least one joint/bursa | Choice based on literature they had reviewed | More likely | 3.46 (1.85-6.48), p < 0.001 |

| Family medicine training | Less likely | 0.21 (0.07-0.64), p = 0.006 | |

| Use bupivacaine in at least one joint/bursa | Non-academic practice setting | More likely | 1.55 (1.04-2.32), p = 0.032 |

| Volume of injectate | |||

| Use low volume (<3mL) | Choice based on what they learned in fellowship training | Less likely | 0.26 (0.09-0.72), p = 0.010 |

| Choice based on what they learned in residency or medical school training | More likely | 1.75 (1.08-2.84), p = 0.022 | |

| Years in training (1-5 years) | Less likely | 0.12 (0.02-0.02), p = 0.042 | |

| Use high volume (>7mL) | Choice based on literature they had reviewed | Less likely | 0.51 (0.32-0.83), p = 0.006 |

| Years in training (1-5 years) | Less likely | 0.15 (0.04-0.67), p = 0.013 | |

| Years in training (6-10 years) | Less likely | 0.16 (0.04-0.70), p = 0.015 | |

Figure 2 -.

Dose of corticosteroid used in large joint/bursal injections, examining only triamcinolone or methylprednisolone (dexamethasone and betamethasone dosages excluded). The vertical axis represents the percentage of physicians who primarily use each dose of corticosteroid for each injection type. N values for each joint/bursa were as follows: hip (n = 330), greater trochanteric bursa (n = 465), knee (n = 541), pes anserine bursa (n = 292), glenohumeral (n = 435), subacromial (n = 518).

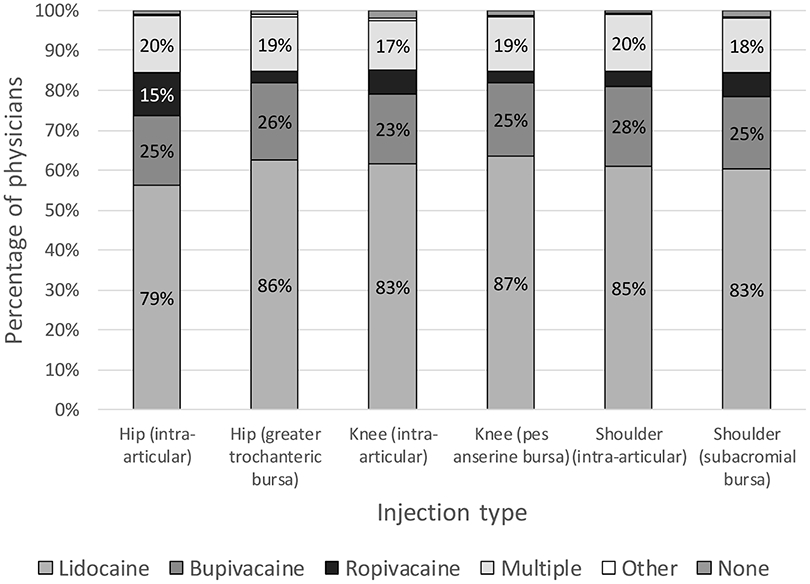

Local anesthetic use

Figure 3 illustrates the types of local anesthetics used – 17-20% used multiple types, 23-28% used bupivacaine, and 79-87% used lidocaine, depending on the location of the injection. Of those who use lidocaine, 79% primarily use it in all joints/bursae. Those who reported that their injectate choice was based on what they learned during fellowship training were more likely to use lidocaine for all joint/bursae injections (OR = 1.85 [1.13-3.02], p = 0.014), as seen in table 2. Those who reported that their injectate choice was based on literature that they had reviewed were less likely to report using lidocaine for all joint/bursa injections (OR = 0.41 [0.27-0.62], p < 0.001) and more likely to use ropivacaine during at least one type of joint or bursa injection (OR = 3.46 [1.85-6.48], p < 0.001). 90.5% (610/674) reported using an anesthetic other than ropivacaine for at least one type of joint or bursa injection. Respondents who reported family medicine as their primary specialty were less likely to use ropivacaine in at least one type of joint injection (OR = 0.21 [0.07-0.64], p = 0.006). Non-academic physicians were more likely to use bupivacaine in at least one type of joint or bursa injection (OR = 1.55 [1.04-2.32], p = 0.032).

Figure 3 -.

Types of local anesthetic used in large joint/bursal injections. The vertical axis represents the percentage of physicians who primarily use each type of local anesthetic for each injection type. N values for each joint/bursa were as follows: hip (n = 401), greater trochanteric bursa (n = 575), knee (n = 647), pes anserine bursa (n = 382), glenohumeral (n = 524), subacromial (n = 641).

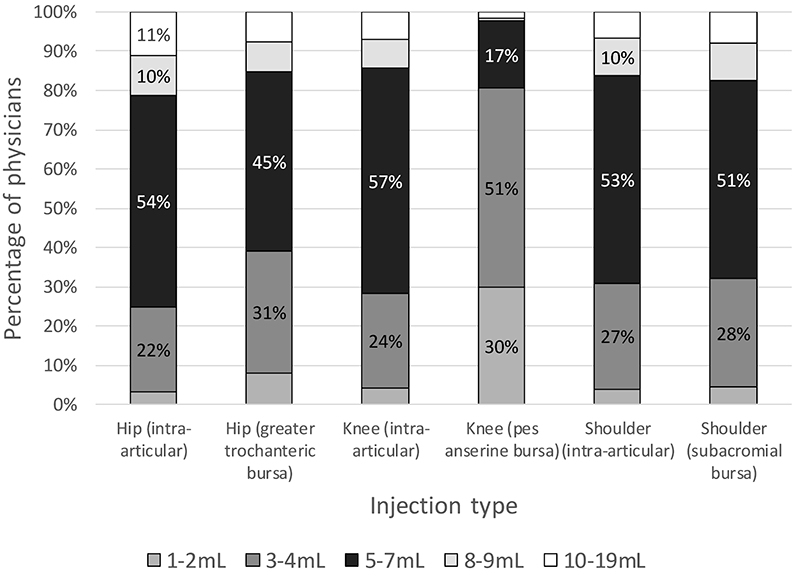

Volume of injectate

Figure 4 demonstrates the volumes of injectate primarily used by respondents, which includes the combination of corticosteroid, local anesthetic, and any other injectate (e.g. saline). Based on interquartile ranges, “low” volumes were 1-2mL while “high” volumes were at least 8mL. Excluding the pes anserine bursa, most physicians used 5-7mL (45-57%), while fewer used 3-4mL (22-31%). For the pes anserine, most (51%) used 3-4mL, while 30% used 1-2mL. Those who reported that their injectate choice was based on what they learned during fellowship training were less likely to use a low volume in a joint or bursa injection (OR = 0.26 [0.09-0.72], p = 0.010), as seen in table 2. Those reporting that their decision was based on what they learned in medical school or residency were more likely to use a high volume in a joint or bursa injection (OR = 1.75 [1.08-2.84], p = 0.022). Those who reported that their decision was based on literature they had reviewed were less likely to use a high volume in a joint injection (OR = 0.51 [0.32-0.83], p = 0.006). Years in practice related to both high- and low-volume outliers, with significant values observed for physicians in practice for 1-5 years (less likely to use a high volume, OR = 0.15 [0.04-0.67], p = 0.013; or a low volume, OR = 0.12 [0.02-0.92], p = 0.042) and 6-10 years (less likely to use a high volume, OR = 0.16 [0.04-0.70], p = 0.015).

Figure 4 -.

Volume of injectate (corticosteroid + local anesthetic + other) used in large joint/bursal injections. The vertical axis represents the percentage of physicians who primarily use each injectate volume for each injection type. N values for each joint/bursa were as follows: hip (n = 401), greater trochanteric bursa (n = 575), knee (n = 647), pes anserine bursa (n = 382), glenohumeral (n = 524), subacromial (n = 641).

Discussion:

This study describes current practice patterns for large joint/bursa corticosteroid injections amongst sports medicine physicians. It is the largest study of its kind, and demonstrates several notable patterns among corticosteroid choice, local anesthetic choice, and volume of injectate used.

Triamcinolone and methylprednisolone were used far more commonly for large joint/bursal injections than other corticosteroids. Physicians noted that their main rationales included information gained in fellowship and clinical experience, with less than half citing literature review. Interestingly, those who based their decision from what a colleague taught them post-training were less likely to use the same corticosteroid type for all joints. This could be due to deriving knowledge from several colleagues (and thus exposure to different practice patterns). Prior studies have shown that triamcinolone and methylprednisolone are the most commonly-used medications in glenohumeral joint and subacromial bursa injections,4,10 though for hand/wrist injections, betamethasone is used more often than methylprednisolone.10 Further, in studies of large joints, these two medications have been used almost ubiquitously in the past 20 years.3 In the present study, most physicians tended to use the same corticosteroid for all injections, regardless of joint. Triamcinolone and methylprednisolone have been compared directly in a few studies, with similar efficacy reported between triamcinolone acetate and methylprednisolone acetate.22-26 Thus, physicians may simply choose a single medication for a particular reason (cost, comfort, convenience, formulary, etc.) and continue to use it exclusively. Of note, triamcinolone hexacetonide demonstrates superiority to other corticosteroids in the knee,27-29 but it is no longer on the market in the United States.

As methylprednisolone and triamcinolone are both commercially available in 40mg vials, it is likely that most respondents use a 40mg dose when they indicated the “21-40mg” choice. Most prior studies have used 40mg as the dose of choice for large joint and bursal injections.3 Only one study has shown superior results for 80mg;20 hip injections with methylprednisolone showed superior improvement in pain, stiffness, and disability at 12 weeks, compared to 40mg. Other studies have shown similar effectiveness regardless of 20mg, 40mg or 80mg dose in the subacromial space,30,31 knee,27,32 or glenohumeral joint.33 Thus, in the context of this literature, for all large joint and bursa, other than for the hip joint, use of doses greater than 40mg of methylprednisolone or triamcinolone are unlikely to provide additional treatment benefit, and potential only increase the likelihood of known complications associated with corticosteroid use. As such, a third of respondents in this survey study appear to be using steroid doses above those in the literature, with the lower proportion represented by pes anserine bursa injections and the highest proportion represented by intra-articular knee injections.

Local anesthetic choice mirrored the findings of corticosteroid choice. Lidocaine was used by most respondents, with 79% administering this local anesthetic in every large joint/bursa injection. Interestingly, those who used lidocaine often were less likely to base their decision on review of the literature. Lidocaine users may be more likely to base their decision on their training, or alternately, on considerations of cost or availability. Non-lidocaine users tended to base their decision on review of the literature; it is likely that this observed practice pattern is due to knowledge of potential chondro- and tenocyototoxicity. These potential toxicity concerns are directly clinically applicable to these large joint and bursa (peri-tendinous) injections. Ropivacaine appears to be less toxic than bupivacaine and lidocaine,16,18,34 though it is more expensive. Family medicine-trained physicians were more likely to use lidocaine for all joints/bursa injections, which may be related to patient population, cost, training differences.

Most respondents used 5-7mL for all large joints and bursae, with the exception of the pes anserine bursa, most likely due to its smaller size. Physicians in practice for a shorter duration of time since training (1-5 years) were more likely to use moderate-volume injections (middle two quartiles), while those in practice for longer (6-10 years) were more likely to use a larger volume. It is unclear why this is the case. Minimal clinical research has been performed on the volume of injectate. One study that examined the effect of volume during hip joint injection for the treatment of pain related to osteoarthritis demonstrated no difference between 3mL and 9mL.21 One in vivo study performed in rats demonstrated that the great degree of chondrocyte survival occurred in association with use of a solution that extrapolates in the human hip to a mixture of 9mL of buffered 0.2% ropivacaine with 1mL of 10mg/mL triamcinolone acetonide,35 though this study has not been repeated in humans.

There are limitations to the present study. First, non-response bias (a type of selection bias) always occurs in studies with incomplete response rates. However, this issue is very common in survey studies of physicians36,37 and the response rate from this present study is greater in magnitude than many similar survey studies of musculoskeletal specialists.4,7-9 Second, all potential rationales for injectate choice may not have been captured, as discrete multiple-choice options were provided rather than a free-text option. This study design decision was made in order to facilitate objective categorical data analysis. Third, members from the AMSSM were queried, but this sample may not be representative of all musculoskeletal providers who perform corticosteroid injections; previous literature has demonstrated differences in corticosteroid usage amongst specialties.4 Physiatrists, outside of sports medicine, often perform these injections and were not surveyed.

Conclusion:

This is the largest study to date examining the large joint and bursae corticosteroid injection practice patterns. It appears that triamcinolone and methylprednisolone are the most commonly-used corticosteroids, most physicians use 21-40mg of corticosteroid for all injections, and lidocaine is the most-often used local anesthetic. Ropivacaine is used exclusively by less than 10% of physicians; thus, its limited use may have detrimental effects on cartilage and tendons. A third of practitioners appear to be using high-dose corticosteroid injections (>40mg) outside of available evidence base. Injectate volumes are most commonly reported to be 5-7mL for large joints and bursae, with the exception of the pes anserine bursa, which is most commonly 3-4mL. Most providers tend to use the same corticosteroid and anesthetic for all injections.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine in allowing the dissemination of a research survey to their members. The authors would also like to thank the members who took the time to complete the survey.

Appendix:

Survey questions:

Where do you predominantly practice?

What is your primary practice setting?

What is your primary specialty or subspecialty?

For how many years have you been in practice, after training?

Where did you do the majority of your training with joint injections (e.g. residency, fellowship)?

Which steroid type do you most commonly use for [each type of injection]?

What steroid dose do you most commonly use for [each type of injection]?

Which local anesthetic do you most commonly use to mix with the steroid for [each type of injection]? This does not include the local anesthetic for numbing the skin, if applicable.

What is the total volume of injectate (including steroid AND local anesthetic) that you most commonly use for [each type of injection]? For example, 1mL of steroid + 4mL of local = 5mL injectate.

- What are the main reason(s) that you use to choose a steroid and local anesthetic for an injection?

- What I learned in fellowship

- What I learned in residency or medical school

- What I learned from colleagues after training

- Based on guidelines

- Based on literature I have reviewed

- Based on clinical experience

- Based on what's available (e.g. hospital formulary)

- No specific basis

References

- 1.Miller JH, White J, Norton TH. The value of intra-articular injections in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1958;40-b(4):636–643. http://www.bjj.boneandjoint.org.uk/content/jbjsbr/40-B/4/636.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright V, Chandler GN, Morison RA, Hartfall SJ. Intra-articular therapy in osteo-arthritis; comparison of hydrocortisone acetate and hydrocortisone tertiary-butylacetate. Ann Rheum Dis. 1960;19:257–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cushman DM, Bruno B, Christiansen J, Schultz A, McCormick ZL. Efficacy of Injected Corticosteroid Type, Dose, and Volume for Pain in Large Joints: A Narrative Review. PM R. 2018;10(7):748–757. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29407227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skedros JG, Hunt KJ, Pitts TC. Variations in corticosteroid/anesthetic injections for painful shoulder conditions: comparisons among orthopaedic surgeons, rheumatologists, and physical medicine and primary-care physicians. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:63. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17617900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deshmukh AJ, Panagopoulos G, Alizadeh A, Rodriguez JA, Klein DA. Intra-articular hip injection: does pain relief correlate with radiographic severity of osteoarthritis? Skelet Radiol. 2011;40(11):1449–1454. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00256-011-1120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacMahon PJ, Eustace SJ, Kavanagh EC. Injectable corticosteroid and local anesthetic preparations: a review for radiologists. Radiology. 2009;252(3):647–661. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19717750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centeno LM, Moore ME. Preferred intraarticular corticosteroids and associated practice: a survey of members of the American College of Rheumatology. Arthritis Care Res. 1994;7(3):151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson JE, Klein SE, Putnam RM. Corticosteroid injections in the treatment of foot & ankle disorders: an AOFAS survey. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(4):394–399. http://fai.sagepub.com/content/32/4/394.long. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaspar J, Kaspar S, Orme C, de Beer J de V. Intra-articular steroid hip injection for osteoarthritis: a survey of orthopedic surgeons in Ontario. Can J Surg. 2005;48(6):461–469. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3211735/pdf/20051200s00008p461.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kegel G, Marshall A, Barron OA, Catalano LW, Glickel SZ, Kuhn M. Steroid injections in the upper extremity: experienced clinical opinion versus evidence-based practices. Orthopedics. 2013;36(9):e1141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedly JL, Comstock BA, Standaert CJ, et al. Patient and Procedural Risk Factors for Cortisol Suppression Following Epidural Steroid Injections for Spinal Stenosis. PM R. 2016;8(9S):S159–S160. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27672767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dragoo JL, Danial CM, Braun HJ, Pouliot MA, Kim HJ. The chondrotoxicity of single-dose corticosteroids. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(9):1809–1814. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00167-011-1820-6. Accessed December 23, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Habib GS, Bashir M, Jabbour A. Increased blood glucose levels following intra-articular injection of methylprednisolone acetate in patients with controlled diabetes and symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(12):1790–1791. http://ard.bmj.com/content/67/12/1790.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habib GS, Miari W. The effect of intra-articular triamcinolone preparations on blood glucose levels in diabetic patients: a controlled study. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17(6):302–305. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21869712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Younes M, Neffati F, Touzi M, et al. Systemic effects of epidural and intra-articular glucocorticoid injections in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Jt Bone Spine. 2007;74(5):472–476. http://ac.els-cdn.com/S1297319X07001911/1-s2.0-S1297319X07001911-main.pdf?_tid=d8889b8a-be2c-11e6-80d6-00000aacb361&acdnat=1481301230_f3899cb3c8a713d56e5da7453825f16e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreuz PC, Steinwachs M, Angele P. Single-dose local anesthetics exhibit a type-, dose-, and time-dependent chondrotoxic effect on chondrocytes and cartilage: a systematic review of the current literature. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(3):819–830. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28289821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dragoo JL, Braun HJ, Kim HJ, Phan HD, Golish SR. The in vitro chondrotoxicity of single-dose local anesthetics. Am J Sport Med. 2012;40(4):794–799. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22287644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sung CM, Hah YS, Kim JS, et al. Cytotoxic Effects of Ropivacaine, Bupivacaine, and Lidocaine on Rotator Cuff Tenofibroblasts. Am J Sport Med. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42(2):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson P, Keenan AM, Conaghan PG. Clinical effectiveness and dose response of image-guided intra-articular corticosteroid injection for hip osteoarthritis. Rheumatol. 2007;46(2):285–291. http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/content/46/2/285.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young R, Harding J, Kingsly A, Bradley M. Therapeutic hip injections: is the injection volume important? Clin Radiol. 2012;67(1):55–60. http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0009926011003059/1-s2.0-S0009926011003059-main.pdf?_tid=538778ec-fda3-11e5-b830-00000aacb35d&acdnat=1460131542_2d4a9091390e8bb50c5d3845cbb6eb50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakeni RA, Al-Nimer MS. Comparison between intraarticular triamcinolone acetonide and methylprednisolone acetate injections in treatment of frozen shoulder. Saudi Med J. 2007;28(5):707–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chavez-Lopez MA, Navarro-Soltero LA, Rosas-Cabral A, Gallaga A, Huerta-Yanez G. Methylprednisolone versus triamcinolone in painful shoulder using ultrasound-guided injection. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19(2):147–150. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/s10165-008-0137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krych AJ, Griffith TB, Hudgens JL, Kuzma SA, Sierra RJ, Levy BA. Limited therapeutic benefits of intra-articular cortisone injection for patients with femoro-acetabular impingement and labral tear. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(4):750–755. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00167-014-2862-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain P, Jain SK. Comparison of Efficacy of Methylprednisolone and Triamcinolone in Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind Study. Int J Sci Study. 2015;3(5):58–62. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yavuz U, Sokucu S, Albayrak A, Ozturk K. Efficacy comparisons of the intraarticular steroidal agents in the patients with knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(11):3391–3396. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00296-011-2188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pyne D, Ioannou Y, Mootoo R, Bhanji A. Intra-articular steroids in knee osteoarthritis: a comparative study of triamcinolone hexacetonide and methylprednisolone acetate. Clin Rheumatol. 2004;23(2):116–120. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15045624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valtonen EJ. Clinical comparison of triamcinolonehexacetonide and betamethasone in the treatment of osteoarthrosis of the knee-joint. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl. 1981;41:1–7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6765509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blyth T, Hunter JA, Stirling A. Pain relief in the rheumatoid knee after steroid injection. A single-blind comparison of hydrocortisone succinate, and triamcinolone acetonide or hexacetonide. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33(5):461–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akgun K, Birtane M, Akarirmak U. Is local subacromial corticosteroid injection beneficial in subacromial impingement syndrome? Clin Rheumatol. 2004;23(6):496–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong JY, Yoon SH, Moon do J, Kwack KS, Joen B, Lee HY. Comparison of high- and low-dose corticosteroid in subacromial injection for periarticular shoulder disorder: a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(12):1951–1960. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22030233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Popma JW, Snel FW, Haagsma CJ, et al. Comparison of 2 Dosages of Intraarticular Triamcinolone for the Treatment of Knee Arthritis: Results of a 12-week Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(10):1865–1868. http://www.jrheum.org/content/42/10/1865.long. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoon SH, Lee HYJ, Lee HYJ, Kwack KS. Optimal dose of intra-articular corticosteroids for adhesive capsulitis: a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sport Med. 2013;41(5):1133–1139. http://ajs.sagepub.com/content/41/5/1133.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Busse P, Vater C, Stiehler M, et al. Cytotoxicity of drugs injected into joints in orthopaedics. Bone Joint Res. 2019;8(2):41–48. https://online.boneandjoint.org.uk/doi/10.1302/2046-3758.82.BJR-2018-0099.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sola M, Dahners L, Weinhold P, van der Horst A Svetkey, Kallianos S, Flood D. The viability of chondrocytes after an in vivo injection of local anaesthetic and/or corticosteroid: a laboratory study using a rat model. Bone Jt J. 2015;97-B(7):933–938. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26130348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vydra D, McCormick Z, Clements N, Nagpal A, Julia J, Cushman D. Current Trends in Steroid Dose Choice and Frequency of Administration of Epidural Steroid Injections: A Survey Study. PM R. May 2019. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31119858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brtnikova M, Crane LA, Allison MA, Hurley LP, Beaty BL, Kempe A. A method for achieving high response rates in national surveys of U.S. primary care physicians. Graetz I, ed. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202755. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]