Abstract

Government policies on abortion are a longstanding topic of heated political debates. The COVID-19 pandemic shook health systems to the core adding further to the complexity of this topic, as imposed national lockdowns and movement restrictions affected access to timely abortion for millions of women across the globe. In this paper, we examine how countries within the European Union and the United Kingdom responded to challenges brought by the COVID-19 crisis in terms of access to abortion. By combining information from various sources, we have explored different responses according to two dimensions: changes in policy and protocols, and reported difficulties in access. Our analysis shows significant differences across the observed regions and salient debates around abortion. While some countries made efforts to maintain and facilitate abortion care during the pandemic through the introduction or expansion of use of telemedicine and early medical abortion, others attempted to restrict it further. The situation was also diverse in the countries where governments did not change policies or protocols. Based on our data analysis, we provide a framework that can help policy makers improve abortion access.

Keywords: Abortion, Policy change, Access, COVID-19, Telemedicine

1. Introduction

On March 11th 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the state of pandemic for the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) [1], with Europe considered as the epicenter of the outbreak. By April 3rd 2020, more than 3.9 billion people (half of the world's population) were placed in some manner of lockdown or quarantine, as governments in more than 90 countries called on their citizens to stay at home to prevent the spread of the virus [2]. The year 2020 will likely be marked in history books as the time when a global pandemic shook modern health systems worldwide and changed our perceptions of healthcare [3,4].

COVID-19 not only presented itself as a health hazard, but also as a cause for great social and economic impact, especially for women [5]. Among the many areas affected by COVID-19, Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) have faced significant disruption. The family-planning organization Marie Stopes International estimates that there could be up to 2.7 million additional unsafe abortions performed as a consequence of COVID-19 [5]. The organization reports that increased barriers to abortions appeared everywhere due to lockdowns, restrictions of movement, lack of information, overwhelmed health system and supply chain disruptions. The time-sensitive nature of access to abortion was highlighted as a particular concern in a joint report by the European Parliamentary Forum (EPF) for reproductive rights and the International Planned Parenthood Federation European Network (IPPF EN) [6]. According to the report, over 5.633 static and mobile clinics, and community-based care outlets across 64 countries were closed because of COVID-19 restrictions, directly affecting access to abortion. Similar events have led the United Nations Population Fund to raise concern over a global surge of up to 7 million unwanted pregnancies as a consequence of lockdowns and lack of access to contraceptives [7].

Access to abortion and public policy related to SRHR have been the subject of heated debates between various actors for decades [8,9]. Many have a claim in this discussion, including governments, policy makers, patients, the medical community, religious institutions, patient advocacy groups and other interest groups. Furthermore, policy decisions “do not happen in a vacuum” of a nation state, but in a transnational setting [9]. Looking into the settings such as the European Union (EU) or the United Kindgdom (UK),in which member states share certain goals, decisions and resources, is important for understanding policy decisions and public debates around abortion during the time of crisis that COVID-19 imposed.

Policy making is said to be path dependent [10], so to understand how and why certain countries changed, or decided not to change their policy on abortion access, previous policy decisions need to be taken into account. Previous studies explored the topic of abortion access and its evolution in the EU and the UK) before the pandemic [9,11]; and certain studies analyze policy responses during the pandemics, partially covering EU countries and the UK [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. Keeping this in consideration, we decided to explore the following research questions: What were the reported difficulties to abortion access during the COVID-19 pandemic in the EU and the UK? How did relevant actors approach the difficulties, and what kind of policy or protocol changes were made (or not) on access to abortion? What kind of public debate followed these reported difficulties or changes?

Generally, Europe is considered to be among the most advanced regions in the world for issues of SRHR. Abortion policy in Europe has been gradually developing since 1960s, making access to abortion more liberal [9]. According to a recent report by the Center for Reproductive Rights, “over 95% of women of reproductive age live in countries that allow abortion on request or on broad social grounds” [18]. However, the situation between European countries is disparate, and different levels of restrictions are in place in various countries. Several studies compare abortion access and public policy in Western Europe, and have found that approaches range from very permissive to very restrictive [9,19]. There are different dimensions to this issue, such as the autonomy of the medical community, the dimension of patient access and the dimension of public health care coverage [19].

Over the past decades, abortion care has seen developments that have facilitated the practice of “medical abortion” through pharmacological drugs such as mifepristone and misoprostol, enabling more convenient early abortion procedures [11]. The use of medical abortion offers access to safe, effective and acceptable abortion care [11,[20], [21], [22]]. Further, the advent of digital technologies opened up the possibility of telemedicine, which allows provision of healthcare services without having health professionals and patients in the same place. In the context of abortion care, telemedicine is being used for counselling, distributing abortion medication prescriptions, and guidance on the abortion process [23]. The use of technology is a further step towards making early medical abortion (EMA) easier and more accessible, presenting a service option where some or all of the abortion care can take place remotely [24].

Regardless of the overall ease of access to abortion in the EU, the COVID-19 crisis made public health policy disparities more visible [15]. We explore these disparities further.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data collection

We conducted a cross-national exploratory study of abortion policy responses and issues related to abortion access in the field during the COVID-19 sanitary crisis in the EU and the UK. The EU consists of 27 member states, with the estimated population of nearly 448 million in 2020 [25] and almost 1.7 million practicing physicians as of 2018 [26]. As of 31st January 2020, the UK left the EU. However, considering that the transition period lasted until the 31st December 2020, we expanded the analysis to include measures taken within the UK. Data collection predominantly took place between March and November 2020 (where applicable some important information has been updated in January 2021). In March 2020, most countries had entered a state of emergency lockdown (or equivalent term), progressively relaxing restrictions during the summer period. Majority of countries in Europe have entered a second-wave of pandemic around October 2020 [27].

We collected the data from seven main types of sources: 1) current national legislations; 2) local policy decisions; 3) global and regional organizations’ synthetic reports; 4) bulletin reports from NGOs; 5) international media coverage; 6) published peer-reviewed academic studies; and 7) administrative data and statistics (population statistics, GDP per capita, state of telemedicine services and healthcare system structures), extracted from their respective official sources [26,28,29]. In all cases, we used the latest available information, and disclosed where no information was available.

2.2. Data analysis

As a starting point, we consulted the legislation of individual countries which was in place prior to the pandemic, in order to comprehend the state of affairs on abortion access before the pandemic took place. We then proceeded to look into changes of abortion regulations by examining policy decisions taken across the countries. We used official documents issued by governments and relevant ministries, which we downloaded and translated where necessary. This allowed us to analyze the nature, mechanisms, and duration of the different governmental measures. We consulted synthetic reports produced by different global and regional organizations and bodies such as WHO, EPF, IPPF EN, and others. We specifically focused on reports published in the wake of the pandemic, such as a joint report by EPF & IPPF EN on “Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights during the COVID-19 pandemic”. We also consulted information published by different NGOs, such as bulletin reports provided by The Center for Reproductive Rights, an institution that continually monitors the treatment of sexual and reproductive health care in Europe. We corroborated these findings with recently published studies that covered access to abortion during COVID-19. The European countries’ media coverage on abortion helped us understand more closely whether abortion remained accessible during the sanitary crisis, as well as to pinpoint specific issues in the field in case of disrupted access.

2.3. Findings

We started our analysis by examining the state of abortion access in the pre-pandemic times for each country (including access to both surgical abortion and EMA), the reported difficulties in access during pandemic, the actions of policy-makers and reported changes in protocols and practices. Details for each country are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Details of abortion access across the EU and the UK during COVID-19.

| Country | Abortion before COVID-19 | EMA before COVID-19 | EMA at home before COVID-19 | % of EMA in Total Abortions before COVID-19 | Reported difficulties in access during COVID-19 | Changes in Access to Abortion during COVID-19 | Description of changes | Availability of EMA during COVID-19 | Telemedicine in facilitating abortion during COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: Countries that initiated or implemented policy or protocol changes that facilitate access | |||||||||

| France | On request | YES | YES, for the 2nd pill | 64% in 2016 | Mobilizing health facilities and staff in the fight against COVID, travel restrictions | Facilitated access through policy changes | Decree of Minister of Solidarity and Health adopted on April 14th 2020 Recommendations - “COVID-19 rapid responses”, published by the High Health Authority. ● Extended gestational limit for EMA at home from 7 to 9 weeks ● Prescribing medications using telemedicine or phone consultations ● Administrating medicaments in pharmacy Re-debating a bill to improve access to abortion that extends the gestational limit from 12 to 14 weeks, enables midwives to perform surgical abortion up to 10 weeks, and disallows providers to deny abortion care based on personal beliefs. Bill currently waits for a vote in Senate. |

YES | YES |

| UK (England and Wales) | Social & economic reasons, Medical Reasons (to save life or health of a woman), Foetal impairment | YES | YES, for the 2nd pill | 73% in 2019 | Abortion clinic closures due to staff sickness & isolation. | Facilitated access through policy changes | Approval Order of the Department of Health and Social Care of the UK Government on 30 March 2020 Approval Order of the Department of Health of the Welsh Government on 31 March 2020 ● Use of telemedicine and approval for home-use of both mifepristone and misoprostol up to 9 week + 6 days ● New guidelines support non-use of ultrasound at this gestation for example if LMP is certain and no significant risk of ectopic pregnancy. ● Approval for EMA home-use includes postal delivery of medication |

YES | YES |

| UK (Scotland) | Social & economic reasons, Medical Reasons (to save life or health of a woman), Foetal impairment | YES | YES, for the 2nd pill | 83% in 2016 | Abortion clinic closures due to staff sickness & isolation. | Facilitated access through policy changes | Abortions labelled as essential healthcare. Approval Order of the Scottish Government from 30 March 2020 ● Use of telemedicine and approval for home-use of both mifepristone and misoprostol up to 11 weeks+6 days as per Scottish guidelines. New guidelines support non-use of ultrasound at this gestation. ● Approval for home-use includes postal delivery of medication. ● The need to administer anti-D to a patient with a Rhesus negative blood group having medical abortion at 10–12 weeks has been suspended |

YES | YES |

| UK (Northern Ireland) | On request (after the legislation change from October 2019, which came into power on March 31st 2020) | NO | NO | NO DATA | Difficulties in access in the early stages of the pandemic, belated implementation of the new abortion law by the Department of Health. | Facilitated access through implementation of policy changes | New abortion legislation passed in October 2019, came into force on March 31st 2020; but implemented by the Department of Health of the Northern Ireland Government on 9 April 2020. ● Abortion services started to operate in April 2020 for first trimester abortions. ● Use of misoprostol at home currently up to 10 weeks |

YES | NO |

| Ireland | On request; with a Waiting Period | YES | YES, for the 2nd pill | NO DATA | Travel restrictions and social distancing measures; burden on hospitals. | Facilitated access through new protocol. | Revised Model of Care for Termination in Early Pregnancy issued by the Health Service Executive and Department of Health on 7 April 2020. ●Introduced model of remote service for the duration of the pandemic: ● Waived two mandatory visits ● Enabled administration of both medical pills at home up to 9 weeks of pregnancy |

YES | YES |

| Italy | On request; with a Waiting Period and Mandatory Counselling | YES | NO | 17% in 2015 | Over crowdedness of hospitals; travel restrictions; personal beliefs of doctors; problems in some hospitals | Facilitated access through policy changes | Guidelines on Organization of Hospital and Territorial Services during an emergency COVID-19 issued by the Ministry of Health in March 2020. Updated Guidelines of Health Ministry regarding EMA issued on August 13th 2020: ● Change of gestational limit for EMA from 7 to 9 weeks ● Removal of a 3-day hospital stay in order to access EMA ● Provision of EMA extended outside the hospital setting - to local, public health centres and family planning services |

YES | NO |

| Spain | On request; with a Waiting Period | YES | YES, for the 2nd pill | 19% in 2015 | Regional inequality in access | Facilitated access through protocol changes | Order from the Ministry of Health decreed that delivery of the face-to-face information to be delivered electronically during the state of alarm in Catalonia. | YES | NO |

| Portugal | On request; with a Waiting Period | YES | YES, for the 2nd pill | 71% in 2015 | Some difficulties in accessing surgical abortions | Facilitated access through protocol changes | Recommendations by Portuguese Society of Contraception and Clinicians not officially approved but implemented by Obstetrician Services. ● Omit the waiting period. ● Only one visit with a doctor for ultrasound and abortion. ● Postponement of follow-up visit when possible or follow-up visit by telemedicine |

YES | Partial (for follow-up visit) |

| Belgium | On request; with a Waiting Period and Mandatory counselling | YES | NO | 22% in 2011 | Reduced staff, danger of infection, focus in some hospitals only on COVID-19 patients, reduction on the number of people who can accompany the person having abortion. | Facilitated access through protocol changes. | New protocol allowing EMA up to 10th weeks, depends from hospital to hospital (not a legal measure); ● Using telemedicine for prescriptions and abortion pre-meetings. |

YES | Partial (for prescriptions and abortion pre-meetings) |

| Austria | On request | YES | YES, for the 2nd pill | NO DATA, media indicates low. | Travel restrictions; few hospitals enabled access to abortions; economic difficulties; Abortion is not explicitly labelled as essential | Facilitated access through policy changes | Federal Office for Safety in Health Care has granted approval that all gynaecologists can prescribe the Mifegyne® abortion pill. | YES | NO |

| Finland | On socio-economic grounds, Medical and Criminal reasons; | YES | YES, for the 2nd pill | 96% in 2015 | No specific challenges reported, but the current law stipulates that a woman needs testimonials from two doctors, as well as a social or financial justification to terminate her pregnancy (with some exceptions). | Facilitated access through policy changes | Change of local practices (Helsinki) ● Home-use of misoprostol extended up to 10 weeks+0 days (previously 9 weeks+ 0 days) in Helsinki ● Citizen initiative to reform the abortion law |

YES | NO |

| Germany | On request; with a Waiting Period and Mandatory counselling | YES | NO | 23% in 2016 | Long delays to get appointments; not all hospitals provide abortion care; abortion is not explicitly labelled as essential. | Facilitated access through new protocol | Allowing counselling to be available via phone with a digital certification of the consultation. | YES | Partial (phone counselling) |

| Group 2: Countries that initiated or implemented policy or protocol changes that restrict access | |||||||||

| Lithuania | On request; Mandatory Counseling | EMA not defined by law | NO | NO DATA | Travel restrictions, hospitals postponing abortion procedures, women resorting to unsafe online means to access EMA. | Restricted access | ● Abortions not labelled as essential healthcare. ● Some healthcare providers decided to suspend abortion services during quarantine or cancelled planned procedures due to other more urgent COVID-19 related health issues. ● Rhetoric of the Health Minister who encourages women to use quarantine time to reconsider their decision on abortion and consult psychologists. |

YES - under prescription in a Clinic/hospital | NO |

| Poland | On the grounds of: foetal abnormality, rape, incest, and danger to mother's health. | NO | NO | NO DATA | Travel restrictions, doctors unwilling to conduct procedures | Almost completely restricted access to abortion | ● Abortions on the grounds of "foetal abnormality" are no longer considered constitutional, as per ruling of the Polish Constitutional Tribunal from October 22, 2020 | NO | NO |

| Romania | On request | YES | No information | NO DATA | Only a small number of public hospitals continues to provide abortions on request (only 40% in November 2020) - reasons for refusal: COVID-19 pandemic, inadequate equipment, but for majority of the hospitals it is related to doctors resorting to “conscientious objection” | Restricted access | ● Abortions not labelled as essential healthcare. ● Order of the Ministry of the Interior issued on March 23rd 2020 suspending all non-essential medical procedures, hospitalizations and consultations in public health facilities. ● Updated Order on April 7th 2020, which expanded the suspensions of all non-emergency procedures to both public and private health facilities. ● On April 27th 2020, Romanian Ministry of Health (Obstetrics & Gynaecology Commission) issued a circular to all District Health Authorities, with a recommendation to include abortion among the emergency services during the pandemic |

NO DATA | NO DATA |

| Slovakia | On request; with a Waiting Period and Mandatory counselling | NO | NO | NO DATA | Hospitals in Slovakia have stopped performing abortions following a government decision to postpone all planned surgeries except lifesaving ones. ● Unavailability of the EMA forces women to more risky procedures. ● The “conscientious objection” restricts access to abortion in some areas. ● Women in the risk of poverty and social exclusion cannot afford an abortion and contraceptives due to financial limitations. COVID-19 pandemic is used to restrict access to abortion services. |

Restricted access | ● Abortions not labelled as essential healthcare. ● Four legislative proposals aiming to restrict further abortion access in the country sent to the Parliament. ● Three proposals requesting the full abortion ban not approved for further negotiations. ● Fourth proposal from the ruling OLANO party, with amendments to the existing Health Care Act and Abortion Act debated and rejected by the Slovak Parliament, by one missing vote on October 20th 2020. ● Rhetoric of the Health Minister who “does not recommend” having an abortion during the crisis. |

NO | NO |

| Group 3: Countries that did not implemented major changes, but abortion access was ensured | |||||||||

| Czech Republic | On request | YES | NO | NO DATA | Some issues in access, as some hospitals did not do abortions. | No changes but abortion considered as essential healthcare. | NA | YES | Partial (for consultations) |

| Slovenia | On request - woman needs to have a clear judgement | YES | NO | NO DATA | No difficulties indicated in the sources, abortions treated as essential healthcare. | No changes | NA | YES | Partial (e-refferals) |

| Denmark | On request | YES | YES | 70% in 2015 | No difficulties indicated in the sources | No changes | NA | YES | YES |

| Sweden | On request | YES | YES - for the 2nd pill | 92% in 2016 | No difficulties indicated in the sources | No changes | NA | YES | YES |

| Estonia | On request | YES | YES, for the 2nd pill | 80% in 2018 | Recommendation to prioritize EMA due to difficulties in access to hospitals and medical facilities. | Minor changes | Recommandations | YES | Partial (for consultations) |

| Greece | On request | YES | YES | NO DATA | Access difficulties for migrant women; delays in the public healthcare | No changes | NA | YES | NO |

| Netherlands | On request; with a Waiting Period and Mandatory counselling | YES | YES, for the 2nd pill | 22% in 2015 | No major difficulties indicated in the sources, with a note that: ● Surgical abortions are less available ● Some difficulties due to unavailability of Telemedicine (Court of Hague example) |

No changes | NA | YES | NO |

| Group 4: Countries that did not implemented major changes, but abortion access was difficult | |||||||||

| Bulgaria | On request | YES | NO | NO DATA | Fewer abortions in comparison to the same time last year, attributed to difficulties in access due to over crowdedness of hospitals. EMA is not accepted or promoted in Bulgaria. Some reports found that access was getting more difficult for Roma girls and women. | No changes | NA | YES | NO |

| Malta | Total ban | NO | NO | NO DATA | Travel restrictions, untimely access to abortions, and emergence of potentially dangerous websites selling fake abortion pills. | No changes | NA | NO | NO |

| Hungary | On request; with a Waiting Period and Mandatory Counselling | NO | NO | NO DATA | Many challenges even before the pandemic. No EMA available. | Ban on non-life threatening procedures | NA | NO | NO |

| Croatia | On request | YES | NO | NO DATA | Reduced staff, doctors rejecting abortion, only a few clinics performed abortions), expensive, travel restrictions ● Attitude of doctors towards abortion is getting more severe and that the abortions are getting more expensive; ● Abortion is not explicitly labelled as essential |

No changes | NA | YES | NO |

| Cyprus | On request | YES | NO | NO DATA | Abortions generally performed only in private hospitals, which during COVID-19 also were taking care of COVID-19 patients. | No changes | NA | YES | NO |

| Unclassified | |||||||||

| Latvia | On request; with a Waiting Period | YES | NO | NO DATA | Insufficient data | No changes | NA | YES | NO |

| Luxembourg | On request; with a Waiting Period | YES | YES - for the 2nd pill | NO DATA | Insufficient data | No changes | NA | YES | NO |

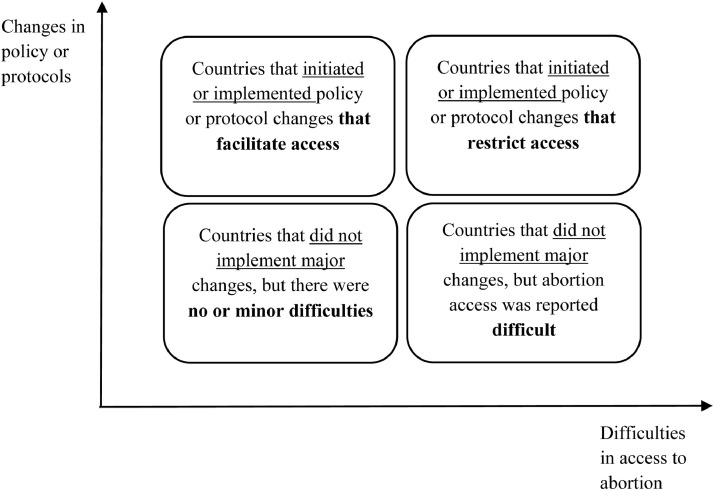

As a result of further analysis, we found two dimensions by which the explored countries differed in relation to abortion access during the COVID-19 pandemic: the extent of changes to policies and protocols within the country, and the extent of difficulty in access to abortion during the pandemic. Based on these two dimensions, we identified four groups of countries: (1) Countries that initiated or implemented policy or protocol changes that facilitated access to abortion, (2) Countries that initiated or implemented policy or protocol changes that restricted the access to abortion, (3) Countries with no policy or protocol change, with no or minor reported difficulties in abortion access indicated in the sources during COVID-19, and (4) Countries with no policy or protocol change with reported difficulties in abortion access during COVID-19 Fig. 1 illustrates these dimensions and groups. We note that for some countries we could not find substantial data, therefore we labeled them as “unclassified”, as we could not categorize them in any of the above-mentioned groups.

Fig. 1.

Reactions of countries within the EU and the UK in relation to abortion access during COVID-19 pandemic.

Each of these categories is described in further detail in the sections below.

-

1.

Countries that initiated or implemented policy or protocol changes that facilitate access to abortion

This group includes countries that recognized the shortcomings of current procedures and policies to abortion care during the pandemic and implemented policy or protocol changes to facilitate access to abortion. The main changes identified in this group relate to one or a combination of the following measures: replacing face-to-face visits with the introduction of different types of telemedicine options (e.g. France, England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Germany, Portugal, Belgium), first-time introduction of EMA (e.g. Northern Ireland, with a note that abortion regulation changes were adopted before the pandemic, while the implementation of these coincided with the period of the pandemic), further facilitation of access to EMA in countries where it already existed by allowing self-administration of both medical pills at home (e.g. France, England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland), postal delivery of EMA medications (e.g. England, Wales, Scotland), extension of the gestational limit for EMA (e.g. Scotland, France, Italy, Belgium, Finland - Helsinki region), elimination of mandatory waiting period (e.g. Portugal), and others. We summarize the situation in individual countries below.

In pre-pandemic France, surgical abortion was available on request until the 12th week of pregnancy (7th week for EMA). The lockdown initiated concerns about women not being able to follow gestational limits due to the challenges that travelling presented during lockdown [30]. France implemented measures to prolong access to EMA at home from 7 to 9 weeks of pregnancy and allowed doctors and midwifes to prescribe medicine by teleconsultation during the pandemic [31]. The amendments to the existing regulation came into effect with the Decree of Minister of Solidarity and Health adopted on April 14th 2020 [32]. Furthermore, a detailed set of recommendations called “COVID-19 rapid responses” were published by the High Health Authority on how to conduct EMA in 8th and 9th week of pregnancy outside of the hospital setting [33]. In addition, the abortion medicaments could now be acquired in pharmacies [14]. The debate around access to abortion continued after the first lockdown. In October 2020, the French Parliament re-initiated a debate about the new abortion regulations (which was previously delayed in 2019) that would extend the gestational limit from 12 to 14 weeks, enable midwives to conduct surgical abortion up to the 10th week, and remove the clause by which doctors and providers could deny abortion care based on personal beliefs [34]. On January 20th 2021, the Senate rejected the proposed extension of the gestational limit and the bill was sent back to the National Assembly for further examination [35].

In England, Wales and Scotland, the grounds on which abortion is considered lawful are stipulated in the Abortion Act 1967 [36] and require two doctors to certify that one of the grounds has been met, to justify the termination of the pregnancy [37]. British Pregnancy Advisory Services (BPAS) reported in March 2020 that nearly one quarter of their abortion clinics were forced to shut down due to staff sickness [38]. On March 30th 2020, the UK Department of Health and Social Care issued the Approval Order [39] to facilitate access to abortion care in England, while similar Approval Orders followed from Welsh [40] and Scottish governments [41] on March 31st 2020. These policy changes introduced telemedicine consultations via phone, video call or other electronic means, as well as facilitated access to EMA by allowing self-administration at home of both mifepristone and misoprostol (previously possible for misoprostol only). For England and Wales this was allowed until up to 9 weeks and 6 days of pregnancy [12], while for Scotland it was extended to 11 weeks and 6 days of gestation [42]. Additionally, postal delivery of the “home package” containing abortion medications is now possible, once home abortion has been approved [14]. The duration of the above-mentioned Approvals for England [39] and Wales [36] is limited to two years or until the expiry of the temporary provisions of the Coronavirus Act 2020; while the Scottish Government did not set an expiration date, but merely indicated its limited time validity until such a time that there is no longer need for a pandemic response, at which point the previous Approval (from October 2017) will be reinstated [41]. It should be noted that public consultations are underway in England [43] and Wales [44]to keep the Approval Orders in place permanently, while they have already been finalized in Scotland [45].

Northern Ireland (NI) is also placed in this group in the light of the recent implementation of the new abortion legislation, which finally decriminalized abortions. Although the bill was approved in July 2019, the fact that it came into force in the wake of the pandemic seemed as a very relevant step when it comes to facilitating abortion access in the country. Abortions in NI were previously illegal and only permitted if there was a risk to the woman's life. The new legislation [46] legalizes surgical abortion within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, and it introduces EMA up to 9 weeks and 6 days gestation, with the possibility for self-administration of misoprostol at home. The law came into force on March 31st 2020, however abortion services were not routinely available in the region before April 9th and there were reported difficulties in access. The NI health authorities initially declined to order the health services to provide abortions, commission information campaigns, which left some women with the only option to travel to England for the procedure during the early days of lockdown in March 2020 [47]. In addition, the government has decided not to follow the emergency measures introduced in the other UK countries concerning the use of telemedicine. This caused several abortion providers to openly express their intention to help pregnant women in NI [12]. In partnership with NI healthcare professionals, the BPAS launched the Emergency Abortion Pills by Post for women in NI [48].

The government of Ireland has also facilitated access to abortion procedures. There was no change to the abortion regulation as such, but an implementation of the revised model of care to the existing legislation in section 12 [49], as it previously did not exclude the possibility of the examination through telemedicine or video conference [50]. Two mandatory personal visits to general practitioners were waived by allowing remote consultations prior to abortion, as well as self-administration at home of the two EMA pills during the pandemic, up to 9 weeks of pregnancy (home-use previously possible for misoprostol only). However, obtaining the Home Care Pack was still subject to collection from a clinic [51].

In Italy, the oversaturation of medical facilities was particularly evident, as the country was one of the hardest hit EU countries by the pandemic. Although the Italian ministry of Health published the Guidelines on Organization of Hospital and Territorial Services during an emergency COVID-19 [52] in March 2020, clarifying that abortion should not be postponed, it failed to explain how to preserve access to voluntary interruption of pregnancy [53]. According to the pre-pandemic abortion legislation, EMA is allowed, but requires hospitalization throughout the entire procedure [54]. Before the pandemic, the EMA accounted less than one fifth of abortions done in Italy [53]. The Pro-Choice Network [55], an Italian contraception and abortion NGO, urged the government to favor EMA by extending the limit for drug administration from 7 to 9 weeks, as well as to de-hospitalize EMA to consultants and outpatient clinics to reduce risk of infection and congestion in hospitals, but the authorities firstly rejected to do so. Nevertheless, on August 13th 2020, Italian Ministry of Health introduced the updated Guidelines [56] regarding EMA, removing the obligatory 3-day stay at the hospital, increasing the limit for EMA to 9 weeks, and allowing for them to take place outside of the hospital setting - in local, public health centers and family planning services [57].

Surgical abortion in Spain is legal and available on request until 14 weeks of pregnancy, with a mandatory waiting period of 3 days [58], while EMA is possible in a hospital or clinical setting, or at home for the self-administration of the 2nd pill [59]. Since the beginning of the health crisis, reports indicate that abortions were treated as essential healthcare, without delays in consultations or cancellations of appointments [60]. Abortion clinics in the country, continued to operate during the state of the emergency [61]. However, the process to request abortion was not sufficiently streamlined in terms of the amount of paperwork and the number of visits required. Spanish women normally need 3 or 4 in-person appointments with healthcare providers before being cleared for the procedure [62]. One of such appointments is called “face-to-face information package” during which a woman needs to collect in person an envelope containing prepared information, and then there is legal requirement of a 3-day mandatory waiting period. This was particularly problematic for women who had to travel long distances during the national lockdown to reach abortion clinics. Most of the country continued following existing procedures requiring physical visits except for Catalonia, which enabled electronic delivery of the “face-to-face information package” since early April [63]. According to the latest reports in the media, the Spanish government wants to amend the abortion legislation to allow 16 and 17-year-olds to seek an abortion without parental permission [59].

Current legislation in Germany allows abortions on request following mandatory counseling and an obligatory waiting period of 3 days [64]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, different organizations and parliamentary groups appealed to the government to recognize surgical abortion as an essential procedure, allow EMA at home, and waive the mandatory waiting period and counseling requirement [65]. Telemedicine support for counseling was introduced to regulate the situation, in a modality via phone with a digital certification [14,66]. Despite these measures, access to abortion was still reported as restricted across the country as many doctors had to close their practices since they belonged to the high-risk age group, and many hospitals refused procedures due to being overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients, with reports of waiting time for an abortion appointment rising up to two weeks [67].

In Austria, surgical abortion was available on request before COVID-19. While EMA was also available, the pill mifepristone had to be taken at the hospital or a dedicated abortion clinic [68]. During COVID-19, already existing issues with abortion access were highlighted, such as traveling to a designated clinic and access to abortion in rural areas [69,70]. In addition, as Austria is one of the rare EU countries where abortion is payed out-of-pocket, the financial and economic crisis in the pandemic presented an additional burden [71]. Reports indicated that only five hospitals in Austria continued to provide abortions [72]. Family-planning centers, women-rights and pro-choice organizations mobilized the political actors to propose a parliamentary motion and allow the delivery of mifepristone by gynecologists at their practice [73]. Federal Office for Safety in Health Care has granted approval and since July 2nd 2020 it is possible to take the abortion pill at the gynecologists, a practice which facilitates access [74].

Abortions in Belgium before the pandemic were allowed on request, but a woman had to go through a waiting period and mandatory counseling [18]. Just before the lockdown, Belgium was about to vote on the modernization of abortion regulations, but this was postponed [75,76]. Abortions are usually handled in hospitals and family panning centers, the latter being the dominant provider, with only 25% of the procedures done in hospitals [77]. Belgium maintained access via family planning centers, which have focused all their available resources on abortion care and urgent gynecological consultations during the pandemic [78]. As explained by Caroline Watillon, project manager at the Secular Federation of Family Planning Centers, "in general, we practice the drug method for up to 7 weeks in the centers. The woman receives a drug and can take it at home. We have received, in particular from the Erasmus hospital, a new protocol which would favor this method up to 10 weeks of pregnancy, because of the current crisis. Each planning center will choose its approach“ [78] . Another new practice was introducing telemedicine for prescriptions and abortion counseling pre-meetings [79].

Reports indicate that the number of pregnancy terminations in public hospitals and private clinics in Portugal decreased by 40% in the period from March to June 2020, in comparison to the same period in the previous year [80]. Although there was no official policy change [14] with regards to abortion access facilitation, the Portuguese Society of Contraception and Clinicians issued in March 2020 a set of recommendations with proposed strategies for health professionals for ensuring access to abortion as essential health care [81]. These included elimination of face-to face visits and encouragement of telemedicine options, postponement of post-abortion visits or making them available via telemedicine, and the option to eliminate mandatory 3-day waiting period (to be decided between the doctor and the user). Reports indicate that hospitals in the National Health System (NHS) were not using uniform approaches – some decided to temporarily suspend abortion consultations to make room for other, more urgent procedures and directed patients towards the private clinics, according to the NHS protocol [80].

Under the current law, abortion in Finland is available on broad social grounds, and a woman is required (except in specific cases) to justify her decision to terminate pregnancy with a testimonial from two doctors and social or financial justification [82]. A citizen initiative gathered more than 50.000 signatures during the COVID-19 crisis to support the regulation change [83]. During the pandemic, there had been a change in the local practice for the region of Helsinki, where the home-use of misoprostol is now allowed up to 10 weeks (previously 9 weeks) [14].

-

2.

Countries that initiated or implemented protocol changes that restrict access to abortion

This group is characterized by the fact that abortion access during the pandemic was severely disrupted or even completely blocked for women due to actions of the government. In summary, the governments of Poland [84] and Slovakia [85] have initiated legislation changes to further restrict abortion access during the COVID-19 pandemic, while in Romania [86] and Lithuania [87] the procedure was not considered essential healthcare, implying that hospitals could simply refuse to conduct interventions during the pandemic, which many of them did.

Poland has one of the most restrictive abortion laws in the EU. It is one of the two EU member states where abortion on request or broad social grounds is not permitted (along with Malta) [88]. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, abortion was considered illegal, except in circumstances such as fetal abnormality, risk to the mother's health, or when the pregnancy results from rape or incest [89]. Even then, finding a doctor willing to conduct the procedure remains complicated. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Polish Parliament debated a “Stop Abortion” legislative proposal, which attempts to additionally limit access to abortion care. This government initiative has generated massive online protests in the country in April 2020, accusing the Polish government of taking advantage of the pandemic to pass this controversial bill [84]. On October 22nd 2020, the Polish Constitutional Tribunal ruled in favor of the motion initiated by the deputies of the ruling “Law and Justice” party, confirming that abortions on the grounds of fetal abnormality are no longer considered constitutional [90]. This almost completely blocks abortion access to women in the country, taking into account that abortions on the grounds of fetal abnormality represented nearly 98% of all abortion procedures in Poland in 2017 [91]. The ruling triggered massive protests, assembling over 100,000 people in Warsaw [92], which culminated in the violence between the protestors and the police forces. Although the government initially delayed the publication and the implementation of the Tribunal's ruling, it came into effect on January 27th 2021, three months after the initial ruling [93].

Similar trends were present in Slovakia and Lithuania. One of the measures to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic was to postpone all non-essential procedures in hospitals and abortion was not labeled as “life-saving procedure” [85]. The consequence of such action was that many hospitals in both countries stopped providing them. Controversial rhetoric from government officials accompanied their public addresses. Lithuanian health minister declared that this could be an opportunity for women to “reconsider their choice” [87], while the Slovakian health minister warned that he “does not recommend” having an abortion during the crisis [94]. As a response to the restricted access to abortion services, representatives of the civil society and the Slovak Ombudsperson have urged the health minister to ensure women's access to safe and timely abortion care [95]. The debate became more intense as several members of the parliament from the current Prime Minister Igor Matovic's party, announced their intentions to push for a full ban on abortions in Slovakia [85]. In September 2020, four legislative proposals aiming to further restrict abortion access in the country were sent to the Parliament [96]. Three proposals advocated for a complete ban of abortions on request, but were not approved for further negotiations. The final proposal (no. 154) came from the ruling OLANO party, with amendments to the existing Health Care Act and Abortion Act. Among other things, the amendments targeted the increase of the mandatory waiting period to 96h (instead of current 48h), introduction of two mandatory medical opinions when resorting to abortion due to medical reasons (instead of one), as well as an obligation for women to disclose the reason for the requested abortion, along with other private information [97]. On October 20th 2020, the Slovak Parliament rejected the proposal by one vote [98].

Different reports indicate that access to abortion remains restricted during the pandemic in Romania [31]. Under normal conditions, abortion on request is possible within the first 14 weeks of pregnancy, while the Medical College's Code of Medical Ethics allows doctors to refuse the procedure on the basis of “conscientious objection” [99]. As part of COVID-19 emergency measures, the Ministry of the Interior issued the Order on March 23rd 2020, suspending all non-essential medical procedures, hospitalizations and consultations in public health facilities [86]. On April 7th 2020, the Order was updated, expanding the suspension to private health facilities. Consequently, numerous abortion and ob-gyn services were discontinued in hospitals in early April 2020. On 15th April 2020, a group of pro-choice Romanian advocates called upon Romanian Ministry of Health to reinstate abortions as part of essential health care on a national level [100]. As a response to this public outcry, the Obstetrics & Gynecology Commission of the Romanian Ministry of Health issued a circular to all District Health Authorities, with a recommendation to include abortion among the emergency services to be provided during the pandemic. However, this recommendation was apparently a subject to free interpretation by health institutions since only 11% of public hospitals in the country were providing abortions on request in April 2020 [101]. The BBC news confirmed that the situation continued throughout the month of May 2020 [102], with the latest media reports from November 2020 indicating that only 40% of state hospitals in Romania provide abortions on request. Reasons for refusal are related to COVID-19 pandemic, inadequate equipment, but “conscientious objection” seemed to be the main cause to deny women the right to abortion [103].

-

3.

Countries with no policy or protocol change where no or minor reported difficulties in abortion access during COVID-19

A series of countries did not make major policy changes, while maintaining abortion accessible during the pandemic, at least partially in the same way that it would under normal circumstances. However, within these countries, there are still differences, mostly due to the state of abortion care before the pandemic, and availability and familiarity with EMA.

In the Czech Republic, the authorities have ordered that the provision of health services should be limited to essential and necessary, but “the measure did not explicitly prohibit abortions”, as the representatives of the Ministry of Health indicated [104]. Reports state that some hospitals may have stopped abortion care for a while due to focus on COVID-19 patients, but indicated that this did not seem to have a big negative impact, as a large part of abortions was already done through EMA, and doctors were encouraged to use telemedicine to conduct necessary consultations [105].

In Estonia, both medical and surgical abortion remained accessible, as confirmed by major health clinics in the country [106]. In order to reduce risk of contagion, women were encouraged to prioritize EMA when possible, as indicated in the “Frequently Asked Questions for COVID-19” on the website of the East Tallinn Central Hospital [107]. However, some organizations criticized the Estonian government for not providing enough elaborated information for women seeking abortions and pregnant women in general, while the elaboration on other health issues on the state website kriis.ee was notable [108].

Abortions were considered as an emergency procedure in Slovenia, and the National Institute of Public Healthconfirmed that no major difficulties are encountered [109]. It has to be noted that differences in approach depending on judgement calls from the healthcare provider could be observed in the field, as one doctor pointed out: “in some cases, we issue an e-referral for hospital treatment, while in others the woman undergoes a preliminary examination by her gynecologist” [110].

In Denmark and Sweden, where EMA constitutes at least 70% of all abortion procedures [6] the situation was less debated. In both countries abortion was supported by telemedicine, in Sweden for Stockholm region specifically even prior to pandemic [14], with no major reports during COVID-19 on difficulties in access.

The Netherlands is one of the countries with lowest abortion rates in the world [111]. Surgical abortions are performed on request until 24 weeks of pregnancy with a mandatory 5-day waiting period [112]. EMA is allowed up to 9 weeks [113] of pregnancy using a 2-pill combination, and the first one needs to be taken in clinics. Although there were no major reported problems in access, in the wake of the pandemic calls were made to the authorities to liberalize the current regulations and use the support of telemedicine [114]. There was an instance in which two women who wanted to have an EMA presented a case against the Dutch government on the grounds that the imposed national lockdown and movement restrictions do not permit women to access their abortion rights [115]. The matter reached the Court of Hague when two pro-abortion organizations joined the legal proceeding. One of the women in the lawsuit, for example, could not leave her household to reach the clinic since her family member was infected with COVID-19 and she was quarantined as a result of it. The plaintiffs requested for an alternative solution to be enabled, such as receiving abortion pills via post, or making them available in pharmacies or with general practitioners. The Court of Hague rejected the case by publishing the judgment [116]in which it refused to allow access to EMAvia alternative methods and invited the plaintiffs to comply with the existing abortion regulations.Abortions in Greece are available on request until the 12th week of pregnancy. It has been reported that during the pandemic, many Greek women choose to see a private gynecologist to avoid delays that are common with the public system [117]. Difficulties for migrant woman in access are also highlighted [118].However, even though Greece does not have official data on abortions, reports indicate that EMA was a method that many women used with the possibility to buy the prescribed medication in the pharmacy and take it at home [119].

-

4.

Countries with no policy or protocol changes, with many reported difficulties in abortion access during COVID-19 crisis

In this group, we find countries in which there were no policy changes initiated during the health crisis to make abortion more accessible, and the already existing difficulties remained and became more complex due to the national lockdowns and disruptions of health systems.

Malta is the only EU member state where there are no instances in which abortion is legally permitted. Estimates indicate that over 500 women in Malta find ways to access abortions each year [15], either by travelling abroad or ordering medical abortion pills online. A report from the Doctors of Choice organization highlights that around 200 women in the country purchase medical abortion pills online each year [120]. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic the probability for higher rates of unsafe abortions has risen, as women had to resort to alternative practices [15]. There has also been evidence of unreliable and potentially dangerous online websites selling fake abortion pills, with symptomatic emergence of these vendors between March and May 2020 [121].

Even before the pandemic, the access to abortion in Hungary was problematic, following several controversies in the period between 2010 and 2013. These controversies include instances by the government, such as different anti-abortion campaigns, modification of the Constitution to include right to protection of life since conception, obstructions to the licensing of abortion pill, and providing state funding to hospitals who agreed not to perform abortions [122]. Hungarian law allows pregnancy to be terminated up to the 12th week if the woman's life is in danger, if there is fetal impairment, a situation of a crisis for a woman or if the pregnancy is outcome of a criminal act. Before the abortion, a woman has to go to Family Planning center twice to receive information about state support and adoption. During the pandemic, the government did not ease these requirements. Furthermore, Hungary was one of the two EU countries (along Poland) that signed an US-led anti-abortion declaration in October 2020 [123]. Hungary's Family Affairs Minister reportedly said that Hungary joined to “show the value of life” [124].

As pointed out by the Open Democracy organization, the Balkans region has been particularly affected by clinic closures, and reports from the IPPF EN and the EPF found that some services for Roma girls and women have been suspended across Bulgaria [125]. Additionally, it is stated that the number of abortions decreased in the country in comparison with the same time last year, which was attributed to difficulties in access [126]. In Croatia, local media inform of rising difficulties, predominantly as a result of increasing abortion fees and rising number of refusals of care by individual providers, as well as hospitals [127]. The abortion policy during COVID-19 times in Cyprus was not elaborated. However, the challenges in accessing abortions remained, since although abortions on request are allowed in Cyprus, only private hospitals perform these procedures, and they were demanded to also treat the COVID-19 patients [128].

2.4. Unclassified countries

Academic studies indicate that abortion access was difficult in Latvia and Luxembourg in a way that women who were suffering from COVID-19 were denied access to hospitals [14]. Luxembourg allows termination of pregnancy only for risks related to physical and mental health since 1978 [129]. In Latvia, surgical abortion is allowed on request until the 12th week and EMA is available. No other specific information was found on the access during COVID-19 crisis, and no major debates were found in the media. Hence, due to a lack of evidence these countries remained unclassified within the four groups.

3. Discussion

In this paper, we set out to explore the state of abortion access within the EU and the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. By comparing the countries within this transnational setting, we identified the diverse impact of COVID-19 on abortion access and the policy measures that countries can take to facilitate abortion access.

3.1. Impact of COVID-19 on abortion access

Abortion has always been a political issue [9], and COVID-19 affected how EU member states and the UK carried on with their public health policies in various ways, making access to abortion differ even more than before. Obstacles to safe abortion have existed in normal times, but particular social, political and geographical barriers have risen in several EU countries during the pandemic, in contrasts with other member states. This makes the impact of COVID-19 to the lives of women seeking abortion differ significantly. The differences between right and left, conservative and liberal, pro-choice and against, became more explicit during the COVID-19 crisis, while inequities to abortion access were highlighted, and the debates around abortion heated up.

On one hand, the COVID-19 pandemic acted as a trigger in some countries to update their abortion policy to a more liberal version during and potentially even beyond the pandemic. As our analysis shows, policy changes such as those implemented or initiated in Austria, Finland, Belgium, Italy, England, Wales, Scotland and France can significantly improve lives of women seeking abortion during and after pandemic. On the other hand, several EU countries, such as Slovakia and Poland pushed for restrictions. Some of the previous attempts to restrict the abortion access were renewed during the pandemic, for example in Slovakia where after six bill drafts concerning abortion rights were rejected in 2019, four of them again found their way into parliament in this crisis period. It is also important to note that the lockdown and borders closure affected access in unexpected ways since women from more restricted countries could not travel to countries with liberal access. Medical tourism, that is traveling to another country for medical care [130], was a common solution for these women before the lockdown (for example from Poland and Slovakia to Czech Republic, Austria and Germany; from Croatia to Slovenia). Access to safe abortion became impossible for women from Malta who then resorted to imported “abortion pills” [15].

Media backlashes emerged from feminist, women rights and pro-choice organizations, warning about “conservative revolution” and leading to protests of abortion activists after the lockdown in the streets [131]. Over 100 organizations united in a joint civil society initiative to draft an open letter to EU policymakers to denounce actions that further endanger women's rights, and potentially put their lives at risk [132]. Reactions were coming also from other countries within the EU, such as for example from Czech Republic and Denmark, where certain organizations and parliament members asked from their governments to facilitate abortion access for Polish women in these countries [133].

Nevertheless, even countries with more liberal policies saw difficulties in abortion access. While the lack of reaction from certain countries clearly shows that the governments did not place a high priority to solving the issues of women seeking abortions, even in countries that took steps to ensure the normal functioning of service and provision, women still experienced many difficulties, as our findings have shown.

3.2. Policy recommendations for improving access to abortion

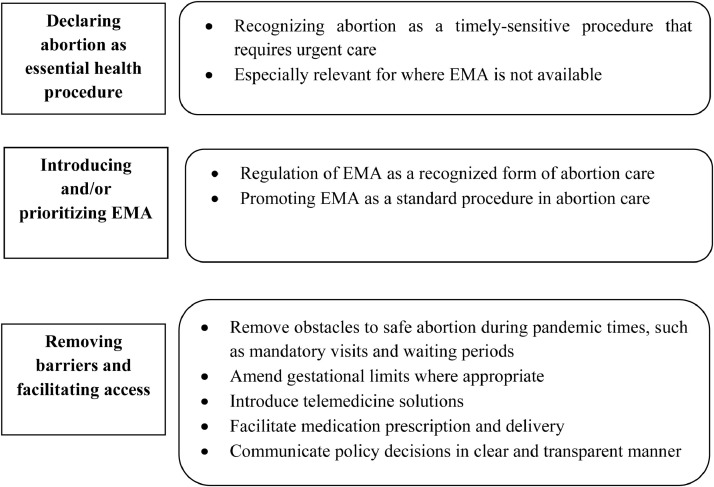

Through our analysis of the reactions of different countries to COVID-19 in terms of access to abortion, and the reported difficulties in the field, we found three kinds of policy measures that countries can decide to pursue and combine to make abortion more accessible during (and beyond) a pandemic situation. We illustrate these measures in Fig. 2 . This framework can help policy makers to identify areas where the abortion access can be facilitated.

Fig. 2.

Three sets of measures in improving access to abortion.

The first measure is declaring abortion as part of essential healthcare. Many countries have proclaimed that the provision of care during the pandemic will be limited to essential and urgent procedures. While some explicitly included abortion as such (e.g. France, England and Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Italy, Spain, Portugal), others failed to do so (e.g. Germany, Austria, Croatia, Romania), or even claimed that abortion should not be counted among the essential procedures (e.g. Slovakia, Lithuania). Abortion is a time-sensitive procedure, and by classifying it as “non-essential”, or failing to classify it as “essential” limits reproductive choices of women and endangers their situation [134]. This is especially important in cases where abortion cannot be done through EMA, and a woman needs surgical intervention.

The second measure refers to the introduction or prioritization and facilitation of EMA. As our data show, the access to abortion was easier within countries in which EMA was a standard before the pandemic. These countries did not have to go through major changes in policy and protocols. However, in some EU countries EMA is still not regulated (e.g. Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Malta, and Hungary). Policy makers in these countries could improve access if they recognize medical abortion as a highly effective and safe procedure [11,20,21]. During pandemic times, EMA can save time and resources at the level of the healthcare system, while providing necessary care for women in a timely and safe manner [135]. The third set of measures relates to improving accessibility to abortion by removing impediments to timely and secure access, and introducing innovations to facilitate abortion. In many of the EU countries women must go through mandatory waiting periods, counseling, mandatory hospital stays or efforts to obtain necessary justifications for abortion. During the pandemic, these types of barriers can mean unnecessary exposure to unsafe environments or prolonging the procedure to the point where the potential abortion falls out of the legal gestational period. Some countries recognized these issues, and either reduced or removed completely different kinds of obstacles, such as gestational limit (e.g. Scotland, France, Italy, Belgium, and Finland - Helsinki region extended gestational limit for EMA), mandatory waiting period (e.g. Portugal), mandatory hospitalization for EMA (e.g. Italy) or mandatory visits (e.g. Ireland), or facilitated the process through telemedicine counseling (e.g. Belgium, Portugal, Germany). Conscientious objection from healthcare workers is recognized within some EU countries, such as Italy and Spain, but its rise was also reported in Croatia during COVID-19 crisis. These are issues that health policy makers need to tackle.

In addition to introducing or prioritizing EMA, health institutions can facilitate access to EMA through support of telemedicine. This can minimize the need for women to travel from home, facilitate medication prescription, or introduce the model of care that enable abortion at home (e.g. in England, Wales, Scotland, France, Ireland). Studies on abortion through telemedicine services found that the need for surgical intervention, the presence of adverse events, and overall patient satisfaction are not statistically different to face-to-face care [136]. In fact, patients often prefer telemedicine-supported services because of the decreased travel and greater availability [137]. However, while evidence suggests that telemedicine abortion services are safe and highly acceptable to those who use it [138], women must seek medical treatment locally if any complications arise. Hospitalization is very rare, but extreme circumstances can require blood transfusions and antibiotic treatments, which, if left untreated, can be life threatening [139]. Availability of telemedicine-supported abortion at home could also potentially facilitate abortion within EU countries where the access is restricted or got restricted during the pandemic. Nevertheless, while clinical aspects of telemedicine are being explored [23], the regulatory issues lag behind [140,141]. When legal local abortion services are not available, women travel to other countries or recur to online purchasing of abortion pills [142]. Transnational trade agreements on services cover situations in which the service itself crosses a border. Under the EU law, at least in theory, health professionals from one country can provide service to patients in another country [140]. In this way, a patient seeking to terminate a pregnancy could use an online medical service to be prescribed abortion pills, which could be then shipped to them. Nevertheless, this is an area that still requires clarification and elaboration from the regulatory bodies. Going further with telemedicine will also require making sure that this does not creates more inequities, as the access to such services may be limited across different social groups. Important actions in facilitating access also lie in the existence and communication of clear, transparent, and detailed protocols and policies, and careful monitoring and adapting to the reported challenges in the field. Through conducting this study, we found that not many countries had explicit instructions on what a woman can do if she needs an abortion during a pandemic situation, while information on many other health procedures was provided. It is easy to imagine that the lack of information can be confusing, and that it could impede women from properly understanding how to access abortion.. Issues such as sexual and reproductive health care are important, and require more efforts, communication, and coordination. Furthermore, as the reported challenges from this study show, the difficulties in abortion access were very much present even in countries where specific measures were taken to facilitate access. Governments and institutions should commit and dedicate resources not only to provide new guidelines and protocols, but also to carefully monitor challenges and adapt policy where and if necessary.

3.3. Limitations and areas for further research

This study has limitations that open up areas for further research. The EU and the UK consist of an array of countries that differ in means of official communication, making it difficult to capture all possible briefings. Additionally, the study did not perform an in-depth analysis of specificity of regions in each country, making it possible that specific region level policy changes were not discovered in our search. Further research could investigate regional level difficulties in access.

Analysis and interpretation were done using the retrieved information. Since the submission of this manuscript, it is possible that newer data could be available through internal channels and publications of each institution or country.

Finally, an interplay of varying complex factors affects policy making, implementation, reporting and dissemination such as local, national, and regional needs, legislations and ruling legal frameworks, political leadership and visions, public discourse around abortion, strength of religious institutions, among many others. Further research could delve into the impact of some of these specific factors on health policy in crisis.

4. Conclusion

COVID-19 shook the health systems worldwide, making abortion care and access problematic in many countries. Our study revolved around three research questions related to the reported difficulties to abortion access during the COVID-19 pandemic in the EU and the UK, how the relevant actors approached the difficulties through policy and protocol changes, and what kind of public debate this yielded. Through an exploratory study of policy responses, we found evidence of major inequities in access to abortion. This study shows that difficulties in access were dependent on the set of measures that Governments decided to take (or not take), in addition to the regulation on abortion already in place. In general, we found that access to abortion was facilitated in countries that recognized abortion as an essential health procedure, prioritized EMA and initiated changes to protocols and policies to remove barriers and improve access. On the other hand, some countries did not facilitate access, but restricted access to abortion.

The decisions of different Governments have created a significant debate in the public. Pro-life groups and abortion-access activist and organizations had heated discussions on the impact of different policies. On the other hand, the temporary measures of some countries made access to abortion easier than it was before the pandemic, empowering women to take care of their health and their bodies in their own homes. The opportunity exists that these temporary measures can be extended to a more permanent state. Further action by the policy makers, and the cooperation between countries, as well as the close collaboration between the Governments and the NGO sector are needed to make it happen.

Acknowledgment

We thank to the Editor and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments in improving this paper. We also thank Dr. Dejan Zec and Dr. Jakov Bojovic for their valuable feedback.

References

- 1.WHO, WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the mission briefing on COVID-19. [Online]. Available from: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-mission- briefing-on-covid-19 [Accessed on 1st March 2020]. Https://WwwWhoInt/Dg/Speeches/Detail/Who-Director-General-s-Opening-Remarks-at-the-Media-Briefing-on-Covid-19—11-March-2020 2020. https://doi.org/11 March 2020.

- 2.Sandford A. Euronews; 2020. Coronavirus: half of humanity now on lockdown as 90 countries call for confinement. https://www.euronews.com/2020/04/02/coronavirus-in-europe-spain-s-death-toll-hits-10-000-after-record-950-new-deaths-in-24-hou accessed May 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bal R., de Graaff B., van de Bovenkamp H., Wallenburg I. Practicing corona – towards a research agenda of health policies. Health Policy. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forman R., Atun R., McKee M., Mossialos E. 12 Lessons learned from the management of the coronavirus pandemic. Health Policy. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wenham C., Smith J., Davies S.E., Feng H., Grépin K.A., Harman S., et al. Women are most affected by pandemics — lessons from past outbreaks. Nature. 2020;583:194–198. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02006-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Planned Parenthood Federation European Network, Sexual and reproductive health and rights during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9467-6_6. (accessed November 1, 2020).

- 7.UNFPA, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic UNFPA global response plan 2020:10.

- 8.Engeli I. Policy struggle on reproduction: doctors, women, and christians. Polit Res Q. 2012 doi: 10.1177/1065912910395323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levels M., Sluiter R., Need A. A review of abortion laws in Western-European countries. A cross-national comparison of legal developments between 1960 and 2010. Health Policy. 2014;118:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greener I. The potential of path dependence in political studies. Politics. 2005;25:62–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9256.2005.00230.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsons J.A. 2017–19 governmental decisions to allow home use of misoprostol for early medical abortion in the UK. Health Policy. 2020;124:679–683. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romanis E.C., Parsons J.A., Hodson N. COVID-19 and reproductive justice in Great Britain and the United States: ensuring access to abortion care during a global pandemic. J Law Biosci. 2020;7:1–23. doi: 10.1093/jlb/lsaa027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romanis E.C., Parsons J.A. Legal and policy responses to the delivery of abortion care during COVID-19. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020 doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13377. ijgo.13377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreau C., Shankar M., Glasier A., Cameron S., Gemzell-Danielsson K. Abortion regulation in Europe in the era of COVID-19: a spectrum of policy responses. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2020-200724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caruana-Finkel L. Abortion in the time of COVID-19: perspectives from Malta. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020 doi: 10.1080/26410397.2020.1780679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bateson D.J., Lohr P.A., Norman W.V., Moreau C., Gemzell-Danielsson K., Blumenthal P.D., et al. The impact of COVID-19 on contraception and abortion care policy and practice: experiences from selected countries. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2020-200709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aiken, A.R.A., Starling, J.E., Gomperts, R., Scott, J.G., Aiken, C., Rubin, J., et al. Demand for self-managed online telemedicine abortion in eight European countries during the COVID-19 pandemic a regression discontinuity analysis. MedRxiv 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Center for Reproductive Rights European abortion laws a comparative overview. Cent Reprod Rights. 2019 https://reproductiverights.org/sites/default/files/documents/European abortion law a comparative review.pdf (accessed November 24, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engeli I. The challenges of abortion and assisted reproductive technologies policies in Europe. Comp Eur Polit. 2009 doi: 10.1057/cep.2008.36. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiala C., Winikoff B., Helström L., Hellborg M., Gemzell-Danielsson K. Acceptability of home-use of misoprostol in medical abortion. Contraception. 2004;70:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raymond E.G., Shannon C., Weaver M.A., Winikoff B. First-trimester medical abortion with mifepristone 200 mg and misoprostol: a systematic review. Contraception. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organisation (WHO), Medical management of abortion. 2018. (accessed November 1, 2020).

- 23.Endler M., Lavelanet A., Cleeve A., Ganatra B., Gomperts R., Gemzell-Danielsson K. Telemedicine for medical abortion: a systematic review. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;126:1094–1102. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fok W.K., Mark A. Abortion through telemedicine. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;30:394–399. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eurostat, EU population in 2020. 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/11081093/3-10072020-AP-EN.pdf/d2f799bf-4412-05cc-a357-7b49b93615f1 (accessed November 1, 2020).

- 26.European Commission, Healthcare personnel statistics - physicians. vol. 28. 2017. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Healthcare_personnel_statistics_-_physicians&oldid=497518#:~:text=There%20were%20approximately%201.7%20million,the%20EU%2D27%20was%20balanced. (accessed November 24, 2020).

- 27.Looi M.-K. Covid-19: Is a second wave hitting Europe? BMJ. 2020;371:m4113. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.EU Health Programme, Overview of the national laws on electronic health records in the EU Member States and their interaction with the provision of cross-border eHealth services. 2013. https://ec.europa.eu/health/ehealth/projects/nationallaws_electronichealthrecords_en (accessed November 24, 2020).

- 29.World Health Organization From innovation to implementation - ehealth in the WHO European Region. Innovation. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.10.008. (accessed November 24, 2020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tribune Il faut « protéger les droits des femmes et maintenir l'accès à l'avortement ». Le Monde. 2020 https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2020/03/31/il-faut-proteger-les-droits-des-femmes-et-maintenir-l-acces-a-l-avortement_6034997_3232.html (accessed November 24, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Center for Reproductive Rights, News in brief on COVID-19 & SRHR in Europe. 2020. https://reproductiverights.org/document/news-brief-covid-19-and-srhr-europe-10-april-3-may (accessed November 24, 2020).

- 32.République française, Décret n 2020-314 du 25 mars 2020 complétant le décret n° 2020-293 du 23 mars 2020 prescrivant les mesures générales nécessaires pour faire face à l’épidémie de covid-19 dans le cadre de l’état d'urgence sanitaire | Legifrance 2020:15–8. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do;jsessionid=DFB679D8DF43FC756CD6CDB0C00449CD.tplgfr30s_3?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000041755775&dateTexte=&oldAction=rechJO&categorieLien=id&idJO=JORFCONT000041755510. (accessed November 24, 2020).

- 33.de Santé H.A. Haute Autorité de Santé; 2020. Interruption Volontaire de Grossesse (IVG) médicamenteuse à la 8ème et à la 9ème semaine d'aménorrhée (SA) hors milieu hospitalier. https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/p_3178808/fr/interruption-volontaire-de-grossesse-ivg-medicamenteuse-a-la-8eme-et-a-la-9eme-semaine-d-amenorrhee-sa-hors-milieu-hospitalier (accessed November 24, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charrier, L. Avortement : vers un prolongement du délai légal de l'IVG en France ? Tv5monde 2020. https://information.tv5monde.com/terriennes/avortement-le-delai-legal-passe-de-12-14-semaines-pour-recourir-une-ivg-en-france-353085 (accessed November 24, 2020).

- 35.Le Parisien avec AFP. IVG : le Sénat refuse d'allonger le délai légal. Le Paris 2021. https://www.leparisien.fr/societe/ivg-le-senat-refuse-d-allonger-le-delai-legal-20-01-2021-8420304.php (accessed January 21, 2021).

- 36.Ministry Health and Social Services The Abortion Act 1967 – approval of a class of place for treatment for the termination of pregnancy (Wales) 2020. Wales. 2020 https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2020-04/approval-of-a-class-of-place-for-treatment-for-the-termination-of-pregnancy-wales-2020.pdf (accessed November 24, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Department of Health and Social Care, Guide to abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2019. London, United Kingdom: 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/891337/guide-to-abortion-statistics-2019.pdf (accessed January 21, 2021).

- 38.British Pregnancy Advisory Service Healthcare professionals call on Boris Johnson to intervene to protect women's health - reckless failure to listen to scientific advice is putting vulnerable women at severe risk. Br Pregnancy Advis Serv. 2020 https://www.bpas.org/about-our-charity/press-office/press-releases/bpas-launches-emergency-abortion-pills-by-post-for-women-in-northern-ireland-amid-shameful-political-gameplay-with-women-s-health-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/ (accessed November 24, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Department of Health and Social Care, The Abortion Act 1967 - Approval of a class of places 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/876740/30032020_The_Abortion_Act_1967_-_Approval_of_a_Class_of_Places.pdf (accessed November 24, 2020).

- 40.Ministry for Health and Social Services, The Abortion Act 1967-Approval of a class of place for treatment for the termination of pregnancy (Wales) 2020 2020. https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2020-04/approval-of-a-class-of-place-for-treatment-for-the-termination-of-pregnancy-wales-2020.pdf (accessed November 24, 2020).