Abstract

Purpose

Many childhood cancer survivors experience disparities due to barriers to recommended survivorship care. With an aim to demonstrate evidence-based approaches to alleviate barriers and decrease disparities, we conducted a scoping review of (1) proposed strategies and (2) evaluated interventions for improving pediatric cancer survivorship care.

Methods

We searched research databases (PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO), research registries, and grey literature (websites of professional organizations and guideline clearing houses) for guidelines and published studies available through October 2020 (scoping review registration: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/D8Q7Y).

Results

We identified 16 proposed strategies to address disparities and barriers endorsed by professional organizations including clinical practice guidelines (N=9), policy statements (N=4), and recommendations (N=3). Twenty-seven published studies evaluated an intervention to alleviate disparities or barriers to survivorship care; however, these evaluated interventions were not well aligned with the proposed strategies endorsed by professional organizations. Most commonly, interventions evaluated survivorship care plans (N=11) or models of care (N=11) followed by individual survivorship care services (N=9). Interventions predominantly targeted patients rather than providers or systems and used technology, education, shared care, collaboration, and location-based interventions.

Conclusions

Published studies aimed at overcoming disparities and barriers to survivorship care for childhood cancer survivors revealed that gaps remain between published recommendations and empirical evaluations of interventions aiming to reduce barriers and disparities.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Additional research is needed to identify evidence-based interventions to improve survivorship care for childhood cancer survivors.

Keywords: Cancer survivors, Health services accessibility, Health equity, Healthcare disparities

Introduction

In the USA, it is estimated that there are more than 500,000 survivors of childhood cancer due to dramatic increases in survival attributed to advances in technology, treatment, and supportive care [1]. Childhood cancer survivors (CCS) face many challenges regarding long-term health outcomes (“late effects”) resulting from their cancer diagnosis and treatment, including adverse physical, psychosocial, functional, and behavioral outcomes [2]. Moreover, CCS exhibit disparities impacting their social, economic, and health-related quality of life outcomes in comparison to healthy peers, including poor academic or professional performance, lower income, and greater prevalence of mental health disorders [3, 4].

Survivorship care is a clinical approach to address the health and wellbeing of cancer survivors, and should be implemented in accordance with evidence-based guidelines using risk-based methods (e.g., according to exposure to potentially harmful therapies) of surveillance, screening, management, and prevention of late effects, in addition to the coordination of care with primary care and other specialty healthcare providers [5]. Despite these guidelines, many CCS do not receive the recommended survivorship care due to various barriers to care, particularly after transitioning into adulthood [5]. As a result of these barriers, disparities exist for a range of clinical, social, economic, and quality of life outcomes among CCS, and this complexity poses unique challenges for research, clinical care, education, and advocacy [2, 5].

While disparities are increasingly recognized, practitioners often are unaware of, or at a loss for how to mitigate, disparities. Effective and efficient access to care is critical to alleviate disparities among CCS who are burdened by the adverse sequelae of their prior malignancy and treatment. We conducted a scoping review of published recommendations and existing evidence for strategies to reduce barriers to and disparities in pediatric cancer survivorship care.

Methods

This scoping review is part of a larger project commissioned by the National Cancer Institute through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Evidence-based Practice Center program [6]. We reviewed proposed strategies endorsed by professional organizations and evaluated interventions aimed at alleviating disparities and reducing barriers to pediatric cancer survivorship care. The review is registered in the Open Science Framework and was determined to be exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board (HS-20-00483) [7].

Data collection

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, research registries, published reviews, and grey literature (websites of professional organizations and guideline clearing houses) for recommendations and published studies to October 2020. Targeted search strategies (detailed in the Supplemental File: Search Strategies and Sources) used “disparity” synonyms and affected populations [8, 9]. We also searched for longitudinal studies in CCS not referring to disparities in the title or abstract.

Eligibility criteria

We included recommendations and intervention evaluations in CCS that addressed disparities and/or barriers to care (see Table S-1). If the definition of CCS was not clearly specified, studies were eligible for inclusion if at least 50% of the sample was diagnosed under the age of 21. The cut-off aligns with the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study inclusion criteria [10].

Screening and abstraction

Literature screening and data abstraction used online software for systematic reviews (DistillerSR). Literature reviewers (authors 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8) screened citations and those determined to be potentially relevant were obtained as full text. As questions arose regarding whether an article met inclusion criteria, these were discussed during team meetings until agreement was achieved. Excluded citations were reassessed using a machine learning algorithm; all citations not confirmed by the algorithm as excluded were screened by an independent human reviewer. Full text publications were screened by two independent reviewers; any discrepancies were resolved through team discussion.

Data were abstracted by one reviewer (authors 4, 5, 6, 7, or 8) and checked by an experienced content expert to confirm accuracy of data collected for all included studies (author 1). Data included publication type and country, study participant characteristics, proposed or evaluated strategies, outcomes assessed, study design, and survivorship care domain.

Results

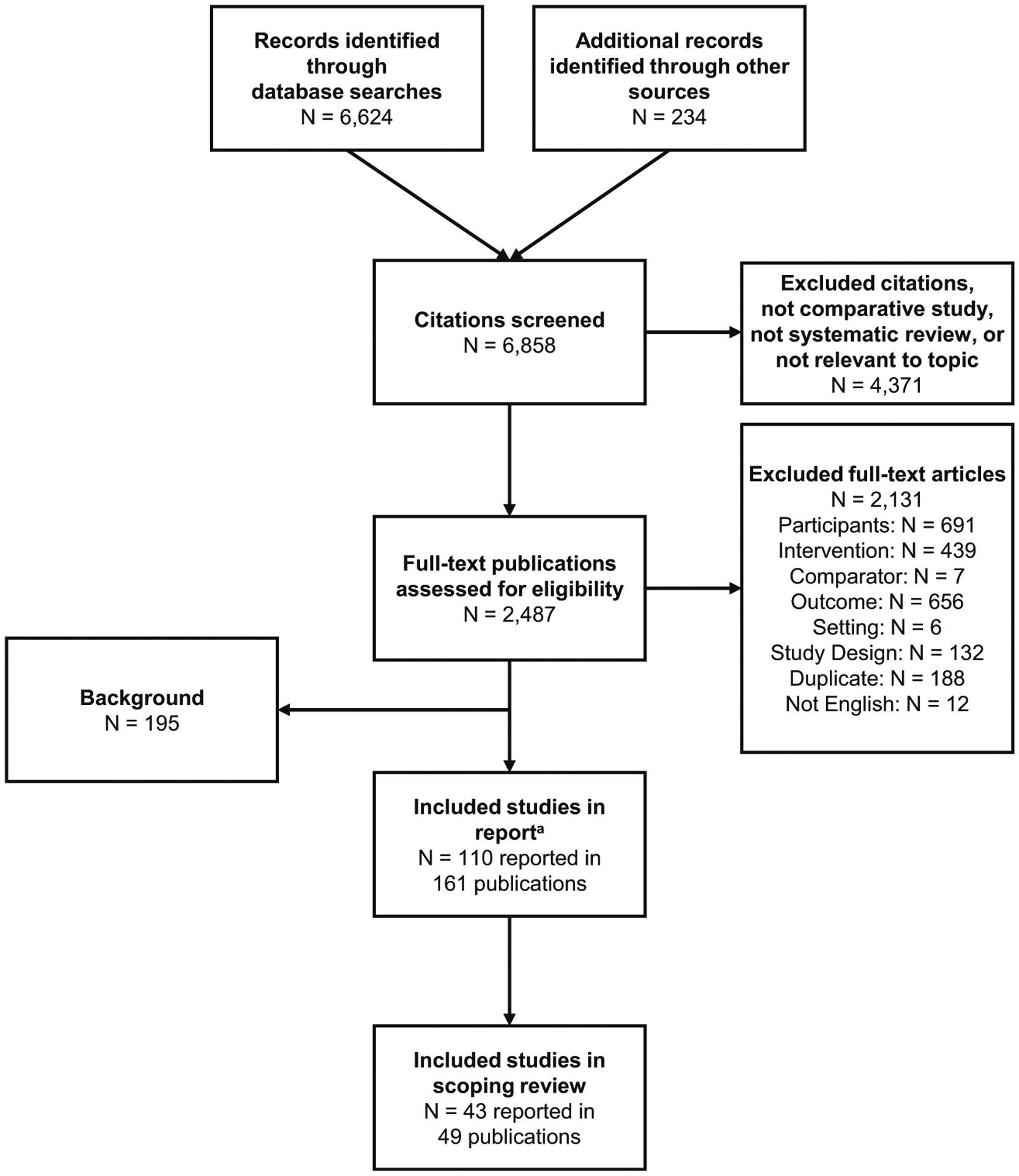

A total of 43 recommendations and intervention evaluations reported in 49 publications met inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram.

aDisparities and Barriers to Pediatric Cancer Survivorship Care available at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Health Care Program: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/pediatric-cancer-survivorship/research

Proposed strategies

We identified 16 recommendations endorsed by professional organizations and entities with interest in CCS (Table 1). All organizations acknowledged disparities regarding pediatric cancer survivorship care, with variation in the level of detail and specific recommendations regarding how to alleviate barriers. In 1996, the International Society of Paediatric Oncology suggested that initiatives focus not only on clinical care, but also on educating the public, informing policy change, and educating CCS about future concerns (such as financial or social issues as a result of their cancer diagnosis and treatment) [11]. In 2003, the National Cancer Policy Board proposed a comprehensive policy agenda to improve healthcare delivery, invested in education and training, and expanded research to improve long-term outcomes for CCS [12]. At the International Society of Paediatric Oncology annual meeting in 2004, a continuum of four types of models of survivorship care were endorsed, ranging from least intensive or involved (survivor is given the responsibility to seek their own follow-up care) to most intensive or involved (new genre of family physicians/internists with knowledge of pediatric cancer late effects and local physicians working in close cooperation with the specialty follow-up clinic) [13]. The Children’s Oncology Group, the UK Children’s Cancer Study Group Late Effects Group, the Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Task Force of the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group, and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network all endorse exposure-based clinical practice guidelines targeting CCS for the surveillance, prevention, management, and treatment of late effects [14–19]. Furthermore, the International Guideline Harmonization Group is developing consistent, effective, and efficient recommendations for CCS [20]. The American Academy of Pediatrics and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) have endorsed specific strategies to minimize the burden of disparities and alleviate barriers to care for CCS [21, 22]. The NCCN clinical guidelines frequently reference assessing barriers to care with the patient; however, the only reference of how to address barriers to care was pertaining to barriers to physical activity [22].

Table 1.

Proposed strategies to alleviate disparities and barriers to pediatric cancer survivorship care

| Organization Year of publication |

Country | Type Title Description |

|---|---|---|

| International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) | Multiple countries | Clinical practice guideline |

| 1996 [11] | SlOP Working Committee on Psychosocial Issues in Pediatric Oncology: Guidelines for Care of Long-Term Survivors | |

| Establish a specialty clinic oriented to the preventive medical and psychosocial care of long-term survivors which includes public education and advocacy. | ||

| National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: National Cancer Policy Board | USA | Policy statement |

| Childhood Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life | ||

| 2003 [12] | Comprehensive policy agenda that links improved healthcare delivery, investments in education and training, and expanded research to improve the long-term outlook for survivors of childhood cancer. | |

| International Society of Paediatric Oncology | Multiple countries | Meeting summaries and recommendations |

| 2004 [13] | Symposium on Long-Term Follow-up Guidelines | |

| Four models of survivorship care were endorsed with strengths and limitations noted. | ||

| UK Children’s Cancer Study Group Late Effects Group | UK | Clinical practice guideline |

| 2005 [14] | Therapy Based Long Term Follow Up: Practice Statement | |

| Exposure-based clinical practice guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors. | ||

| UK Children’s Cancer Study Group Late Effects Group | UK | Clinical practice guideline |

| 2006 [15] | Long-Term Follow-Up of People Who Have Survived Cancer During Childhood | |

| Ideal survivorship strategy captures the largest number of long-term survivors by ensuring that appropriate clinical and psychosocial care, health education, and health promotion are all delivered in an appropriate manner at an appropriate location, while taking advantage of important research opportunities that will benefit future generations of survivors. | ||

| Children’s Oncology Group Nursing Discipline | USA | Meeting summaries and recommendations |

| 2007 [23] | Establishing and Enhancing Services for Childhood Cancer Survivors: Long-Term Follow-Up Program Resource Guide | |

| Healthcare organizations and providers should deliver care and alleviate barriers to survivorship care for pediatric survivors. | ||

| American Academy of Pediatrics | USA | Clinical practice guideline |

| 2009 [21] | Long-Term Follow-Up Care for Pediatric Cancer Survivors | |

| Follow-up care for pediatric cancer survivors concerning detecting serious late effects and promoting healthy lifestyles. | ||

| Late Effects Taskforce of the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group | Netherlands | Clinical practice guideline |

| 2010 [16] | Guidelines for Follow-Up after Childhood Cancer More Than 5 Years After Diagnosis | |

| Exposure-based clinical practice guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors. | ||

| Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network | UK | Clinical practice guideline |

| 2013 [17] | Long Term Follow Up of Survivors of Childhood Cancer | |

| Exposure- and risk-based clinical practice guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors. | ||

| American Academy of Pediatrics | USA | Policy statement |

| 2014 [24] | Standards for Pediatric Cancer Centers | |

| Strategies for helping survivors transition to primary care with emphasis on pediatric cancer centers. | ||

| Working Group on Adolescents, Young Adults, and Transition | Germany | Meeting summaries and recommendations |

| 2017 [25] | Building a National Framework for Adolescent and Young Adult Hematology and Oncology and Transition from Pediatric to Adult Care: Report of the Inaugural Meeting of the Working Group of the German Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology | |

| Establish a solid infrastructure for transition nationwide so that transition in care can start during adolescence. | ||

| Children’s Oncology Group | USA | Clinical practice guideline |

| 2018 [18] | Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers | |

| Exposure-based clinical practice guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors. | ||

| Cancer Leadership Council | USA | Policy statement |

| 2019 [26] | Improve the Delivery of Survivorship Care | |

| Encouraged Congress to explore how to define and finance distinct episodes of survivorship care and encouraged the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to carefully consider what to base payment for survivorship care on. | ||

| National Comprehensive Cancer Network | USA | Clinical practice guideline |

| 2020 [22] | National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Survivorship | |

| Clinical practice guidelines for cancer survivors, including focus on screening for cardiovascular, psychosocial, and chronic pain late effects and receipt of immunizations to prevent infections for pediatric survivors. | ||

| International Guideline Harmonization Group | Multiple countries | Clinical practice guideline |

| 2020 [20] | Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines | |

| Surveillance recommendations regarding what surveillance modalities should be used, at what frequency surveillance should be performed, and what interventions are available if abnormalities are found. | ||

| Children’s Cancer Cause | USA | Policy statement |

| 2020 [27–29] | Childhood Cancer Survivorship Proposal | |

| Endorsed testing of a comprehensive new model of care and survivorship care plan initiative (Child and Survivorship Transition Model), which uses local service delivery and state payment for those covered by Medicaid, coupled with the Children’s Oncology Group record – Summary of Cancer Treatment (Comprehensive) and a survivorship care plan; endorsed improving access to survivorship care via digital technology, improved data collection, and addressing barriers to clinical trial participation for survivors. |

Recently, organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Working Group on Adolescents, Young Adults, and Transition in Germany, and the Children’s Oncology Group Nursing Discipline have endorsed specific strategies to deliver care to CCS, including the use of a survivorship care plan and transition clinics to assist CCS’ and their families with transitioning from pediatric to adult care settings [23–25]. In 2019, the Cancer Leadership Council, representing a variety of cancer-related organizations, suggested that Congress explore how to define and finance distinct episodes of survivorship care and encouraged the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to carefully consider what to base payment for survivorship care on [26]. The Children’s Cancer Cause has endorsed the Child and Survivorship Transition Model, a new survivorship care plan initiative with local service delivery and state payment for those covered by Medicaid, addressing provider and health system barriers to survivorship care including staffing capacity, electronic medical records, interoperability of medical records, and legal constraints regarding confidentiality [27–29].

Evaluated interventions

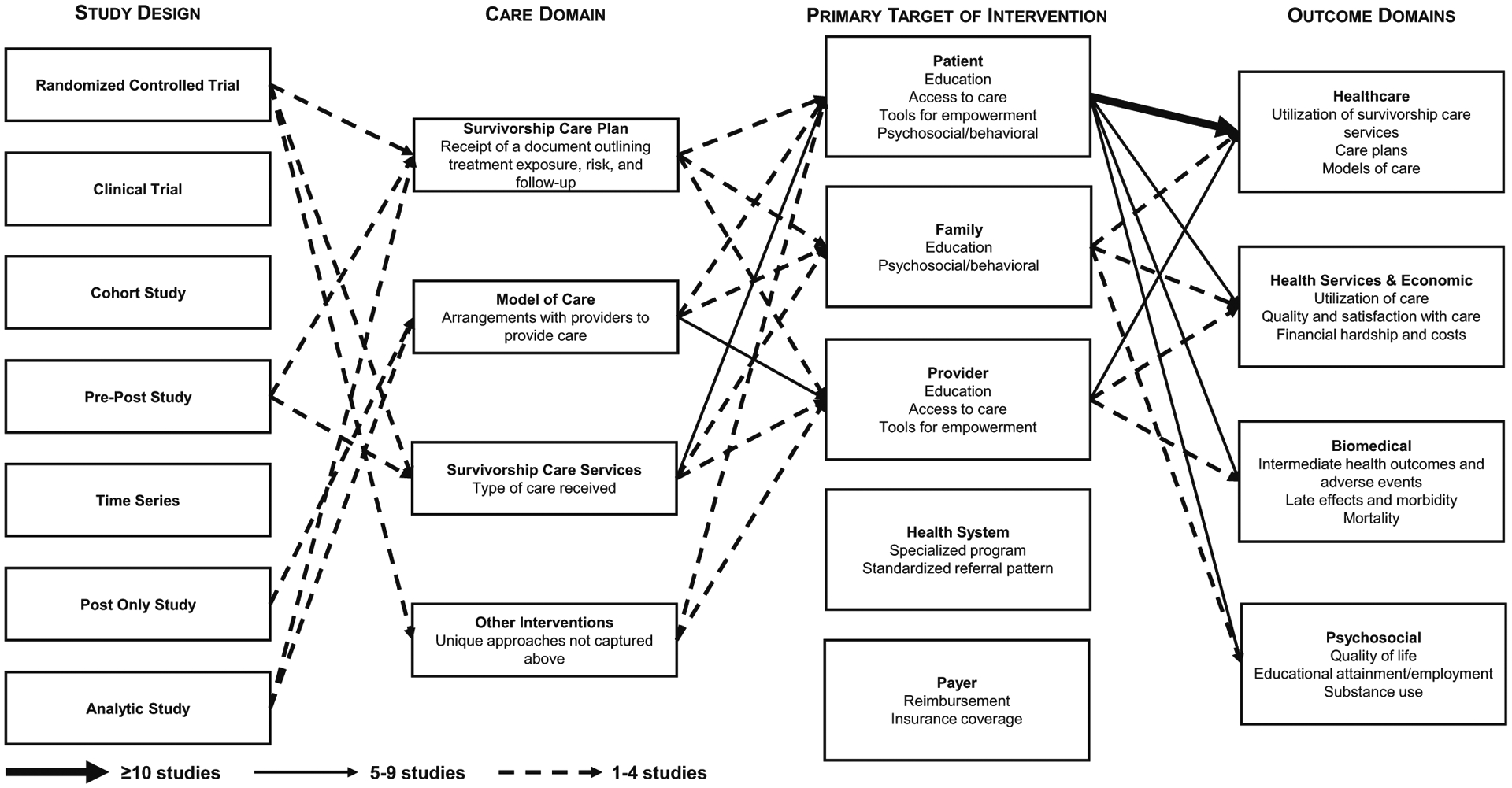

We identified 27 studies reporting on an evaluation of a strategy to alleviate disparities and barriers to pediatric cancer survivorship care (Fig. 2; Table 2). Strategies established survivorship care plans (N=11; e.g., receipt of a document outlining treatment exposure, risk, and follow-up care needs), implementing models of care (N=11; e.g., arrangements with providers to provide care), specific survivorship care services (N=9), and other approaches (N=6). Almost all evaluations were published in the last ten years. With the exception of three studies targeting providers, all used cohorts of patients diagnosed with a variety of pediatric malignancies. Most studies evaluated interventions involving survivorship care plans or models of care (N=11, respectively), followed by survivorship care service (N=9) and other (N=6). The majority assessed survivorship care as a primary or secondary outcome of interest. Studies almost always targeted the patient rather than providers or organizations. Almost half (n=12; 44%) of the evaluated interventions did not report the race or ethnicity of the participants of their intervention studies. Of those that did report the race and ethnicity of their participants, only three studies had samples that were predominantly non-white (see Supplemental File, Table S-2).

Fig. 2.

Evidence base

Table 2.

Research on interventions to alleviate disparities and barriers to pediatric cancer survivorship care

| Survivorship care domain | Number of studies Identified studies |

|---|---|

| Survivorship care plan | N=11 |

| Bashore, 2016 [30]; Blaauwbroek, 2012 [31]; Casillas, 2019 [32]; Hudson, 2020 [33]; Iyer, 2017 [34]; Kadan-Lottick, 2018 [35]; Kunin-Batson, 2016 [36]; Landier, 2015 [37]; Oeffinger, 2011 [38]; Santacroce, 2010 [39]; Williamson, 2014 [40] | |

| Model of care | N=11 |

| Bashore, 2016 [30]; Blaauwbroek, 2008 [41]; Costello, 2017 [42]; Ducassou, 2017 [43]; Eilertsen, 2004 [44]; Ford, 2013 [45]; Hudson, 2020 [33]; Iyer, 2017 [34]; Kadan-Lottick, 2018 [35]; Reynolds, 2019 [46]; Williamson, 2014 [40] | |

| Survivorship care service | N=9 |

| Casillas, 2017 [47]; Casillas, 2019 [32]; Casillas, 2020 [48]; Costello, 2017 [42]; Devine, 2020 [49]; Oeffinger, 2019 [50]; Raj, 2018 [51]; Santacroce, 2010 [39]; Schwartz, 2019 [52] | |

| Other | N=6 |

| Casillas, 2019 [32]; Crom, 2007 [53]; de Moor, 2011 [54]; Iyer, 2017 [34]; Rose-Felker, 2019 [55]; Schwartz, 2018 [56] |

Technology

Ten studies evaluated strategies that used technological-based interventions, all of which involved the patient, two including family and one involving providers. An evaluation of a web-based informational intervention reported no improvement in cancer-related knowledge or anxiety surrounding health beliefs [36]. In another study, CCS reported satisfaction, benefits, and ease of use regarding self-management and use of survivorship care plan as a result of a text messaging pilot [52]. In another text messaging intervention using an ethnically diverse cohort of Hispanic/Latino CCS, participants reported improved knowledge, healthcare self-efficacy, and increased positive attitudes towards survivorship care [32]. An intervention using a photonovela reported improvement in confidence related to survivorship care, cancer stigma among family members, and knowledge of survivorship care among family members [48]. Notably, this study’s entire sample was Hispanic/Latino [48]. One study found text messaging as an acceptable way to communicate with CCS regarding both reminders about upcoming survivorship care needs and tailored suggestions for community resources [47]. Similar sentiments were found in a study using telemedicine to facilitate transition of survivorship care from pediatric oncologists to adult primary care providers (PCP) [42].

The remaining studies evaluated web-based platforms. SurvivorLink provided a personal health record that was securely stored and electronically shared with providers and most survivors and providers found the website user-friendly and the care plan availability helpful [40]. In another study, providing both an electronic and printed survivorship care plan that could be shared electronically with providers resulted in most survivors and providers finding the website user-friendly and the care plan availability helpful [31]. One study reported positive effects for a web-based psychosocial and behavioral intervention called “A Survivor’s Journey” for pediatric brain tumor survivors and caregivers [51]. Another study found that encouragement by CCS’ oncologist or regular doctor to quit smoking resulted in an increase in the number of cessation attempts [54].

Education

A self-management and peer mentoring intervention found a positive relationship regarding transition readiness and grit [49]. An evaluation of an educational intervention targeting CCS who attend a survivorship clinic found female survivors reported higher knowledge than male survivors [53]. Among female Childhood Cancer Survivor Study participants, motivational interviewing showed improved use of screening mammography [50]. Additionally, survivorship care plans mailed to high-risk survivors resulted in improved compliance with guideline-concordant survivorship care [38]. Similarly, a distance-delivered intervention of two personalized telephone counseling sessions increased cardiomyopathy screening among at-risk survivors, therefore improving compliance with guideline-concordant survivorship care [33]. One study assessed the usefulness of a workbook to assist CCS in transition readiness and reported that information regarding medical history, provider information, and insurance are most helpful [30]. A risk-based education intervention among a majority sample of Hispanic/Latino CCS already engaged in a survivorship clinic found an increase in awareness of personal health risk in CCS after three sessions [37].

Three studies evaluated the effect of an intervention addressing healthcare providers. One followed up on survivorship care plans that had been mailed to PCP that the most significant barrier to providing survivorship care was the provider’s lack of knowledge and level of comfort [34]. After completing an educational intervention, pediatric cardiologists reported increased knowledge of CCS’ needs and risks [55]. Lastly, residents’ knowledge, skills, and comfort discussing topics related to survivorship care improved after receiving CCS-focused curriculum [56].

Shared care, collaboration, and location-based strategies

Four studies used shared care models of survivorship care. One examined the effect of shared care between an oncologist and PCP and found improved CCS adherence to survivorship care [43]. However, empowering CCS with the distribution of a survivorship care plan and implementation by PCPs, in comparison to a traditional approach to survivorship care using a survivorship clinic model, resulted in lower adherence to guideline-recommended care and identification of late effects [35]. A phone-based coping skills training that also discussed plans for surveillance among CCS (primary target) and their parents’ (secondary target) found that outcomes improved including post-traumatic growth compared to the control group [39]. A shared care model over three years reported less travel requirements, shorter waiting times for appointments, better patient familiarity with the clinical setting, and less stigmatization [41].

Three studies evaluated collaboration- or location-based strategies to improve survivorship care. One reported that collaboration among CCS, family members, and health professionals in the family’s home community is beneficial and valuable for survivorship care adherence [44]. A second found a higher compliance rate with Children’s Oncology Group-recommended guidelines in cancer-center-based facilities compared to primary care or community-based facilities [46]. A third study found no significant differences in CCS knowledge regarding their cancer diagnosis or potential risk for future health problems among those who attended specialized survivorship clinics when compared to those seen in a non-specialized clinic [45].

Discussion

This scoping review documents proposed and evaluated strategies to overcome barriers and disparities in survivorship care among CCS. Sixteen organizations acknowledged disparities but specific recommendations regarding how to alleviate barriers experienced by CCS are limited. Only 27 published studies empirically evaluated interventions to reduce barriers and disparities to pediatric survivorship care. Studies predominantly focus on addressing barriers at the patient level, most frequently evaluating education-based interventions, followed by access to care and empowerment interventions.

Survivorship care is impacted by various social determinants of health and interplays between barriers at the patient, family, provider, health system, and payer levels. While many social determinants of health can directly impact access to and successful receipt of care, our understanding of why racial and/or ethnic minorities face disparities is unclear and highly complex. As a result, diverse samples of survivors, including those with adequate representation of racial and ethnic minorities, are needed to gain more insight into barriers experienced by populations that experience health disparities and support should be aimed at funding creative ways to overcome these barriers, given the fragmented nature of the US healthcare system. We identified only one study was designed to specifically address disparities in survivorship care rather than aiming to reducing barriers to care [48]. Notably, among the studies that were predominantly non-white, the outcomes of interest improved; therefore, even though not all studies were specifically designed to reduce barriers to care, they may help mitigate barriers for diverse populations [32, 37, 48]. No studies assessed strategies addressing healthcare system or payer levels, despite these being key barriers.

Parents, families, caregivers, and local community members are vital for survivors. However, little is known about their roles longer term. Providers were only cited as the primary target of an intervention when coupled with a patient-targeted intervention; therefore, the impact of community-, family-, and peer-support merits further examination to identify facilitators of care and interventions to foster these protective relationships.

Most current studies that address barriers do so at the patient level. But, multiple levels exist, in which barriers inherently affect certain subgroups of survivors, including barriers at the provider, healthcare system, and payer levels, in addition to interventions targeting the caregivers, family members, and local environment. Insurance and reimbursement constraints serve as barriers at many levels. Federal subsidies could incentivize payers and health systems to provide guideline-concordant survivorship care targeting disparate CCS subgroups to engage these populations in the health system. These proposed interventions would require different comparator groups dependent on the level of intervention, such as (1) those receiving or delivering usual care for interventions at the patient or provider level, (2) contrasting healthcare delivery systems for interventions at the healthcare delivery level, and (3) insurance providers that may provide varying levels of coverage and reimbursement for interventions at the payer level.

It is unclear whether enhanced survivorship care mitigates or prevents the incidence or severity of late effects, and as a result, alternative models merit examination (e.g., improving the precision of risk-based modeling using big data to understand the impact of survivorship care provided through PCPs or telemedicine). Studies currently underway may provide some guidance, including a study explicitly evaluating the National Academies recommendation of using a survivorship care plan to improve cardiovascular outcomes among CCS [57]. Finally, an economics-based approach with representative, actual cost data from various levels would help to truly understand costs and benefits, including the patient, family, provider, health system, and payer perspectives.

This scoping review provides insight into both proposed and evaluated strategies to alleviate or overcome disparities and barriers in survivorship care among CCS; however, there are some notable limitations. We restricted the review to English-language publications which may have missed studies published in other languages. Furthermore, this scoping review explored existing research literature and showed a small evidence base to date. When the field has matured, a systematic review should incorporate risk of bias and provide effect estimates for evaluated strategies, in particular comparative effectiveness of competing strategies.

Conclusion

This scoping review highlights the strengths and limitations of the literature surrounding proposed and evaluated strategies to alleviate disparities and reduce barriers to pediatric cancer survivorship care. Given the growing number of CCS, the lifelong impact of cancer, and the growing aging population, careful attention should be paid to how studies are designed to examine the effectiveness of interventions on reducing barriers and eliminating disparities among CCS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Mary Butler, Paul Jacobsen, Emily Tonorezos, Shobha Srinivasan, Danielle Daee, Amy Kennedy, Lionel Bañez, and Meghan Wagner for their helpful feedback and Drizelle Baluyot for administrative assistance.

Funding information

This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under Contract No. 75Q80120D00009/Task Order 75Q80120F32001. The authors of this document are responsible for its content. The content does not necessarily represent the official views of or imply endorsement by AHRQ or HHS. Authors Erin Mobley and Carol Ochoa were also supported by 5T32CA009492-35 from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Code availability Literature screening and data abstraction used online software for systematic reviews, DistillerSR.

Availability of data and material The data are available in SRDR+ (https://srdr.ahrq.gov/).

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01060-4.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program, SEER cancer statistics review 1975–2016, Table 28.8 [cited 2020 August 7,]; Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2016/browse_csr.php?sectionSEL=28&pageSEL=sect_28_table.08.

- 2.National Research Council, Childhood cancer survivorship: improving care and quality of life. 2003, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirchhoff A, et al. Unemployment among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Medical Care. 2010;48(11):1015–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurney JG, Krull KR, Kadan-Lottick N, Nicholson HS, Nathan PC, Zebrack B, et al. Social outcomes in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(14):2390–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robison LL, Hudson MM. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: life-long risks and responsibilities. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2014;14(1):61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) Program overview. 2020. [cited 2020 December 28]; Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/evidence-based-reports/overview/index.html.

- 7.Mobley EM, Moke DJ, Milam J, Ochoa C, Stal J, Osazuwa N, et al. (2020). Disparities and Barriers for pediatric cancer survivorship care. Open science framework, scoping review, peer-reviewed protocol registration: 10.17605/OSF.IO/D8Q7Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities. About: overview. 2020. [cited 2020 May 27]; Available from: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/.

- 9.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Review and Assessment of the NIH’s Strategic Research Plan and Budget to Reduce and Ultimately Eliminate Health Disparities. 2006, Thomson GE, Mitchell F, Williams MB, editors. Washington (DC: ): National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: overall CCSS cohort demographic and treatment exposure tables. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital; 2021. [cited 2021 April 21]; Available from: https://ccss.stjude.org/content/dam/en_US/shared/ccss/documents/data/treatment-exposure-tables.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masera G, Chesler M, Jankovic M, Eden T, Nesbit ME, van Dongen-Melman J, et al. SIOP Working Committee on Psychosocial issues in pediatric oncology: guidelines for care of long-term survivors. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996;27(1):1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute of Medicine, in Childhood cancer survivorship: improving care and quality of life, Hewitt M, Weiner SL, and Simone JV, Editors. 2003, The National Academies Press: Washington (DC). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldsby R, Ablin A. Surviving childhood cancer; now what? Controversies regarding long-term follow-up. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;43(3):211–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skinner R, Wallace WH, and Levitt GA, Therapy based long term follow up: practice statement: United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group (Late Effects Group). 2nd ed. . 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skinner R, Wallace WH, Levitt GA, UK Children’s Cancer Study Group Late Effects Group. Long-term follow-up of people who have survived cancer during childhood. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(6): 489–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Late Effects Taskforce of the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group (DCOG LATER). Guidelines for follow-up after childhood cancer more than 5 years after diagnosis. 2010; Available from: https://www.skion.nl/workspace/uploads/vertalingrichtlijn-LATER-versie-final-okt-2014_2.pdf.

- 17.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), Long term follow up of survivors of childhood cancer-a national clinical guideline. March 2013, SIGN: Eninburgh. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Children’s Oncology Group, Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers. Children’s Oncology Group, 2018. Version 5.0. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Children’s Oncology Group. Establishing and enhancing services for childhood cancer survivors: long-term follow-up program resource guide. 2007. August 7, 2020]; Available from: http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/LTFUResourceGuide.pdf.

- 20.International Guideline Harmonization Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines. 2020. [cited 2020 July 21]; Available from: https://www.ighg.org/guidelines/.

- 21.American Academy of Pediatrics. Long-term follow-up care for pediatric cancer survivors. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):906–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denlinger C, et al. , Survivorship, Version 2.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Children’s Oncology Group. Establishing and enhancing services for childhood cancer survivors: long-term follow-up program resource guide. 2007. [cited 2020 August 7,]; Available from: http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/LTFUResourceGuide.pdf.

- 24.American Academy of Pediatrics. Standards for pediatric cancer centers. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):410–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Escherich G, Bielack S, Maier S, Braungart R, Brümmendorf TH, Freund M, et al. Building a national framework for adolescent and young adult hematology and oncology and transition from pediatric to adult care: report of the Inaugural Meeting of the ‘AjET’ Working Group of the German Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology. Journal of Adolescent & Young Adult Oncology. 2017;6(2):194–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cancer Leadership Council. Patient-centered care strategies. 2019. [cited 2020 November 9]; Available from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56b50b3527d4bd49bed6e1f2/t/5cccb018104c7b981c278555/1556918308731/Cancer+Leadership+Council+to+Senator+Alexander+re+health+care+costs+and+quality+March+1+2019.pdf.

- 27.Children’s Cancer Cause, Childhood cancer survivorship proposal. 2020.

- 28.Children’s Cancer Cause. Child and Survivorship Transition (CAST) Model. 2020. [cited 2020 November 9]; Available from: https://www.childrenscancercause.org/s/CAST-Model-2020-One-Pager-with-GAO.pdf.

- 29.Children’s Cancer Cause. Cures 2.0 2019. [cited 2020 November 9]; Available from: https://www.childrenscancercause.org/s/CCC-Cures-1.pdf.

- 30.Bashore L, Bender J. Evaluation of the utility of a transition workbook in preparing adolescent and young adult cancer survivors for transition to adult services: a pilot study. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2016;33(2):111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blaauwbroek R, Barf HA, Groenier KH, Kremer LC, van der Meer K, Tissing WJE, et al. Family doctor-driven follow-up for adult childhood cancer survivors supported by a web-based survivor care plan. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(2):163–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casillas J, et al. The use of mobile technology and peer navigation to promote adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivorship care: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(4):580–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hudson M, et al. Increasing cardiomyopathy screening in at-risk adult survivors of pediatric malignancies: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(35):3974–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iyer NS, Mitchell HR, Zheng DJ, Ross WL, Kadan-Lottick NS. Experiences with the survivorship care plan in primary care providers of childhood cancer survivors: a mixed methods approach. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(5):1547–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kadan-Lottick NS, Ross WL, Mitchell HR, Rotatori J, Gross CP, Ma X. Randomized trial of the impact of empowering childhood cancer survivors with survivorship care plans. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(12):1352–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunin-Batson A, Steele J, Mertens A, Neglia JP. A randomized controlled pilot trial of a Web-based resource to improve cancer knowledge in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2016;25(11):1308–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Landier W, Chen Y, Namdar G, Francisco L, Wilson K, Herrera C, et al. Impact of tailored education on awareness of personal risk for therapy-related complications among childhood cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(33):3887–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Smith SM, Mitby PA, Eshelman-Kent DA, et al. Increasing rates of breast cancer and cardiac surveillance among high-risk survivors of childhood Hodgkin lymphoma following a mailed, one-page survivorship care plan. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(5):818–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Judge Santacroce S, Asmus K, Kadan-Lottick N, Grey M. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes from a pilot study of coping skills training for adolescent–young adult survivors of childhood cancer and their parents. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2010;27(1):10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williamson R, Meacham L, Cherven B, Hassen-Schilling L, Edwards P, Palgon M, et al. Predictors of successful use of a web-based healthcare document storage and sharing system for pediatric cancer survivors: Cancer SurvivorLink. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(3):355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blaauwbroek R, Tuinier W, Meyboom-de Jong B, Kamps WA, Postma A. Shared care by paediatric oncologists and family doctors for long-term follow-up of adult childhood cancer survivors: a pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(3):232–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costello AG, Nugent BD, Conover N, Moore A, Dempsey K, Tersak JM. Shared care of childhood cancer survivors: a telemedicine feasibility study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6(4): 535–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ducassou S, et al. Impact of shared care program in follow-up of childhood cancer survivors: an intervention study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(11). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eilertsen ME, Reinfjell T, Vik T. Value of professional collaboration in the care of children with cancer and their families. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2004;13(4):349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ford J, Chou J, Sklar C. Attendance at a survivorship clinic: impact on knowledge and psychosocial adjustment. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2013;7(4):535–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reynolds K, Spavor M, Brandelli Y, Kwok C, Li Y, Disciglio M, et al. A comparison of two models of follow-up care for adult survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2019;13(4):547–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Casillas J, Goyal A, Bryman J, Alquaddoomi F, Ganz PA, Lidington E, et al. Development of a text messaging system to improve receipt of survivorship care in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2017;11(4):505–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Casillas J, et al. , Engaging Latino adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors in their care: piloting a photonovela intervention. J Cancer Educ, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Devine K, Rutgers The State University of New Jersey, and National Cancer Institute, Peer mentoring in promoting follow-up care self-management in younger childhood cancer survivors. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oeffinger KC, Ford JS, Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Henderson TO, Hudson MM, et al. Promoting breast cancer surveillance: the EMPOWER study, a randomized clinical trial in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(24):2131–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Raj SP, Narad ME, Salloum R, Platt A, Thompson A, Baum KT, et al. Development of a web-based psychosocial intervention for adolescent and young adult survivors of pediatric brain tumor. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2018;7(2):187–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwartz LA, et al. Iterative development of a tailored mHealth intervention for adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology. 2019;7(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crom D, et al. Marriage, employment, and health insurance in adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1(3): 237–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Moor J, et al. Disseminating a smoking cessation intervention to childhood and young adult cancer survivors: baseline characteristics and study design of the partnership for health-2 study. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rose-Felker K, Effinger K, Kelleman MS, Sachdeva R, Meacham LR, Border WL. Improving paediatric cardiologists’ awareness about the needs of childhood cancer survivors: results of a single-centre directed educational initiative. Cardiol Young. 2019;29(6): 808–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwartz LF, Braddock CH III, Kao RL, Sim MS, Casillas JN. Creation and evaluation of a cancer survivorship curriculum for pediatric resident physicians. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(5):651–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chow E, et al. Communicating health information and improving coordination with primary care (CHIIP): rationale and design of a randomized cardiovascular health promotion trial for adult survivors of childhood cancer. Contemp Clin Trials. 2020;89:105915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.