Abstract

The social construct of masculinity evolves in response to changes in society and culture. Orthodox masculinity is mostly considered to be hegemonic and is evidenced by the dominance of men over women and other, less powerful men. Contemporary shifts in masculinity have seen an emergence of new masculinities that challenge traditional male stereotypes. This systematic review aims to review and synthesize the existing empirical research on contemporary masculinities and to conceptualize how they are understood and interpreted by men themselves. A literature search was undertaken on 10 databases using terms regularly used to identify various contemporary masculinities. Analysis of the 33 included studies identified four key elements that are evident in men’s descriptions of contemporary masculinity. These four elements, (a) Inclusivity, (b) Emotional Intimacy, (c) Physicality, and (d) Resistance, are consistent with the literature describing contemporary masculinities, including Hybrid Masculinities and Inclusive Masculinity Theory. The synthesized findings indicate that young, middle-class, heterosexual men in Western cultures, while still demonstrating some traditional masculinity norms, appear to be adopting some aspects of contemporary masculinities. The theories of hybrid and inclusive masculinity suggest these types of masculinities have several benefits for both men and society in general.

Keywords: masculinity, inclusive masculinity, new masculinity, social change

Introduction

The concept of masculinity in broad terms can be defined as a social construct that encompasses “the behaviors, languages, and practices, existing in specific cultural and organizational locations, which are commonly associated with men and thus culturally defined as not feminine” (Whitehead & Barrett, 2001, pp. 15–16). Orthodox masculinity is mostly considered to be hegemonic and is evidenced by the dominance of men over women and other, less powerful men (Connell, 1987, 1995; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). Traditional masculinity norms, socialize men to project strength and dominance particularly over others, and the inherent restrictive stereotypes require men to be stoic, independent, tough, and powerful (Courtenay, 2000).

These stereotypes influence men’s individual health outcomes and have societal impacts. Men, in general, have poorer health outcomes and young men are at greater risk from injury, either accidentally through risk-taking activities or self-inflicted. Young men are also less likely to seek health care. This correlates with traditional masculinity norms that reinforce beliefs around the male body being strong (Courtenay, 2000; Mahalik et al., 2007)

In addition, there are socio-negative perspectives consistently found in orthodox masculinity. These include the sexual degradation and objectification of women and the culture of homophobia (Bevens & Loughnan, 2019; Hughson, 2000; Messner, 1992). Both perspectives serve to establish the sexual prowess and heterosexuality of the individual thereby fortifying their masculinity.

However, the social construct of masculinity is not fixed and has always evolved over time in response to changes in society and culture (Britten, 2001; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Waling, 2020; Whitehead & Barrett, 2001 Contemporary shifts in masculinity have seen an emergence of new masculinities that challenge these restrictive traditional stereotypes. Orthodox masculinities and traditional masculinity norms are being challenged and, contemporary culture is embracing the “new male” (Smith & Inhorn, 2016).

The body of global literature dedicated to the Critical Studies on Men and Masculinities clearly demonstrates that the conceptualization of masculinity has evolved and will continue to do so (Bridges & Pascoe, 2018; Britten, 2001; Elliott, 2019). The intersection of class, race, gender, and sexuality all contribute to how masculinity is perceived in specific settings and under specific conditions. It is the combination of these elements that leads to a divergence in traditional masculinity thinking and the emergence of new masculinities (Messerschmidt & Messner, 2018). Contemporary masculinities are now emerging in response to changes in society’s expectations of how men should behave (Britten, 2001; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Whitehead & Barrett, 2001).

These contemporary masculinities include Hybrid masculinities (Demetriou, 2001) and Inclusive Masculinity Theory (Anderson, 2009). The concept of Hybrid Masculinities emerged at the turn of this century with Demetriou’s (2001) recognition that straight white men who occupied positions of power in the masculine hierarchy were beginning to adopt cultural elements of subordinate and marginalized masculinities. The selective integration of these elements into traditional masculinity creates a hybrid wherein the adopters of these elements, remain tough and strong, while being able to show sensitivity (Arxer, 2011; Barber, 2016; Bridges & Pascoe, 2018; Messerschmidt & Messner, 2018; Pfaffendorf, 2017).

Inclusive Masculinity Theory developed from the research findings of Eric Anderson (2009) and is supported by the work of Mark McCormack (2014). Inclusive Masculinity Theory is underpinned by their findings, indicating that homophobia is increasingly being rejected by straight men (Anderson, 2009; Anderson & McCormack, 2018). Moreover, straight men, are including gay peers in social networks and are engaging both emotionally and physically with other men.

Much has been written on these contemporary masculinity theories, including extensive critiques of the disparities between the two. While the behaviors belonging to each of the masculinity theories have been described by researchers, to date there has been no research that synthesizes how men themselves understand and interpret these new masculinities. There is limited evidence of men’s experiences, understanding, and perceptions of contemporary masculinities.

This paper, therefore, aims to systematically review and synthesize the existing peer-reviewed published empirical research on contemporary masculinities to determine how contemporary masculinity is viewed by men themselves, rather than from the point of view of the researcher. This review aims to capture men’s voices regarding contemporary masculine enculturation.

Methods

A search was undertaken on the following databases, MEDLINE, CINAHL, JStor, SocioIndex, Web of Science, Informit Complete, Psychinfo Ovid, ProQuest Social science, ProQuest Central, and Sociological Abstracts. Keywords were identified during extensive reading in the field of Critical Studies on Men & Masculinities. This reading was undertaken in all forms of literature, including empirical research, books, and opinion pieces. Many of the words identified are not “typically” found in the formal literature, however, to be as inclusive as possible and to ensure a rigorous and thorough search, all keywords identified were used.

The medical subject heading (MeSH) “masculin*” was used with the following keywords hybrid, inclusive, emerg*, divergent, oppositional, resistant, dialogical, caring, new, flexible, chameleon, soft-boiled, person*, cool, contemporary, alternate, modern, metrosexual, hipster and bromance.

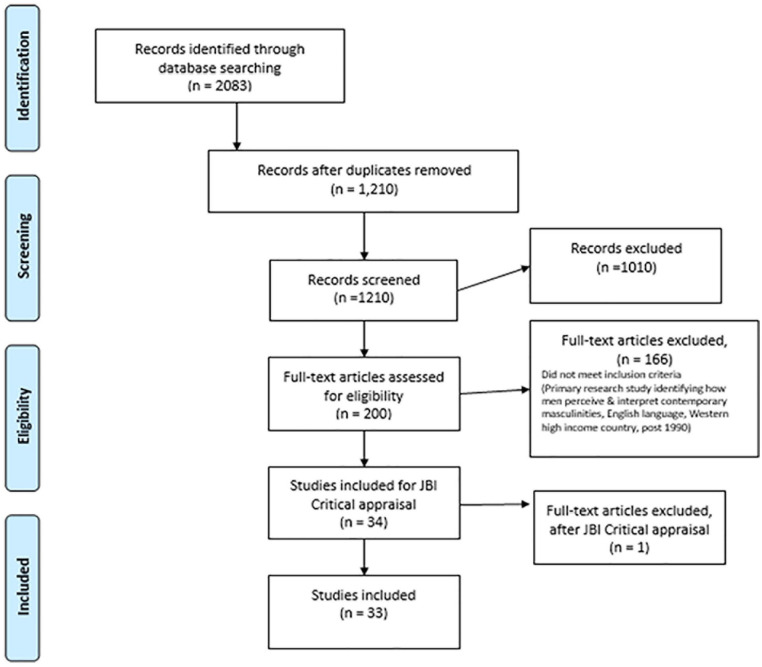

Articles published from January 1, 1990, to October 2019 were reviewed and assessed for eligibility using the PRISMA 2009 checklist for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (Moher et al., 2009) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Chart.

Inclusion criteria are as follows: (a) Empirical peer-reviewed studies, published in journals, identifying how men perceive and interpret, contemporary masculinities; (b) English language; and (c) Research conducted in Western high-income countries. High-income countries are those defined by the World Bank as being such during 2019; and (d) Research conducted since 1990.

Exclusion criteria are as follows: (a) Not empirical research, for example, book, review, opinion piece, conference paper, editorial, letter, dissertation, or non-peer-reviewed publication; (b) The focus was on clinical, medical, chronic disease or health outcomes; (c) Literature that used masculinity as an explanation for male behaviors including “toxic” masculinity, sexual violence, aggression, and gender inequality; and (d) Article was not in English, not conducted in a Western high-income country or conducted before 1990.

The extensive search produced 2,083 records. Records were imported into Covidence software and 873 duplicates were identified and removed. The abstracts of the remaining 1210 records were then screened independently by two authors against the previously identified inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 1,010 records were excluded leaving 200 records to be assessed at full-text stage. At full-text review, all records were read in detail by two authors, and the inclusion, exclusion criteria were applied. Conflicts were resolved by the two authors reaching a consensus following discussion. A further 166 records were excluded following full-text review. Reasons for exclusion were 69 were not empirical research, 2 were pre-1990, 6 were from non-Western countries, 3 were not in English, and 2 were focused on health outcomes. The remaining 84 studies did not identify how males perceive and interpret contemporary masculinities. The excluded studies used masculinity to describe men’s behaviors, including but not limited to, sexual orientation, violence, and “toxic masculinity.” This left 34 studies in total, 32 qualitative studies, and 2 mixed methods studies to be assessed for methodological quality.

Assessment of Methodological Quality

The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklists for prevalence studies (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017a) and qualitative research (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017b) were chosen to assess the methodological quality of the articles, as they are designed to appraise both qualitative and mixed-methods studies specifically (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017a, & 2017b). Scores for each article are included under the Quality Rating column in the summary of Studies (Table 2). The appraisal process was undertaken independently by two authors. Any disagreement was resolved by a third author. One study did not meet the quality appraisal criteria and was excluded from the review, leaving 33 studies in the review.

Table 2.

Summary of Studies.

| Author | Country and setting | Study aim | Study design/methods | Identified masculinity (theoretical background) |

Sample size | Population | Themes | Quality rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams (2011) | North East America Large Liberal College |

Identify existence of more inclusive versions of masculinity | Ethnography Participant observation In-depth Interviews |

Metrosexual Inclusive |

21 | 18- to 22-year-old Heterosexual male soccer players |

Decreased levels of homophobia Emotional bonding Physical contact “metrosexuality’ |

10/10 a |

| Anderson (2005) | USA College | To examine the construction of masculinity among college-age heterosexual male cheerleaders | Qualitative Participant observation In-depth Interviews Focus groups |

Orthodox masculinity Inclusive masculinity |

68 | 18- to 23-year-old Heterosexual male cheerleaders |

Rejection of orthodox masculinity Respect for women Acceptance of gender diversity |

7/10 a |

| Anderson (2008) | USA University | To identify how masculinity is constructed in the setting of university cheerleading | Ethnography Participant observation In-depth Interviews |

Inclusive masculinity | 32 | 18- to 23-year-old males Members of fraternity |

Rejection of homophobia, misogyny Emotional intimacy Rejection of orthodox masculine tenets and hyper-masculinity |

9/10 a |

| Anderson (2011) | Mid-West America Catholic university |

Investigate relationship b/w antifemininity, homophobia & the construction of masculinity in this setting | Ethnography Participant observation In-depth Interviews |

Inclusive masculinity | 22 | 18- to 22-year-old males members of university soccer team |

Decreased levels of homophobia Demonstrations of emotional and physical intimacy Avoidance of fights and violence |

10/10 a |

| Anderson (2012) | England High school students |

To Identify Inclusive Masculinity in a sport education setting | Ethnography Participant observation In-depth Interviews |

Inclusive masculinity | 16 | Sixth form males 15 heterosexual, one gay |

Absence of homophobia Increase of emotional support between male friends Abatement of violence Decrease of hyper-masculine behavior |

9/10 a |

| Anderson & McCormack (2015) | British university | To examine forms of homosocial intimacy among heterosexual

males To explore implications of these behaviors |

Qualitative In-depth semi-structured Interviews |

Inclusive masculinity | 40 | 18- to 19-year-old males Student athletes All heterosexual |

Decreased levels of homophobia Homosocial physical tactility |

8/10 a |

| Anderson & McGuire (2010) | England University rugby team |

To examine how this cohort, construct their masculinity in opposition to many aspects of orthodox masculinity. | Ethnography Participant observation In-depth Interviews |

Inclusive masculinity | 24 | 18- to 22-year-old males Heterosexual |

Rejection/contestation of misogyny

&homophobia Decreased excessive risk taking Emotional support of each other |

10/10 a |

| Anderson, et al. (2019) | USA 11 geographically diverse universities |

To understand the frequency, context and meanings of same-sex kissing | Mixed method study Quantitative surveys In-depth interviews |

Inclusive masculinity Contemporary masculinity |

442 Surveys 75 interview |

18- to 25-year-old males | Decreased levels of homophobia Homosocial kissing |

8/10

a

8/9 b |

| Blanchard et al. (2017) | England Christian school |

To examine the social dynamics of masculinities in 6th form college in a small town in the northeast of England | Ethnography Participant observation Semi-structured interviews |

Inclusive Masculinity | 15 | Working class 16- to 19-year-old boys | Positive attitudes toward homosexuality Physical touching Emotional sharing |

10/10 a |

| Brandth & Kvande (2018) | Norway | Explores how the masculine identities of employed fathers may be affected by caring. | Qualitative Interviews |

Caring Masculinity Inclusive Masculinity Critical positive masculinity |

12 | Fathers who used their entire quota of parental leave to care for child home alone on a full-time basis | Rejection of traditional gender roles Developing intimate relationships with children Putting children and family first Caring and connecting |

9/10 a |

| Caruso & Roberts (2018) | Australia Body Positivity for Guys (Online Blog) | To analyze the complex ways that men construct, represent and perform masculinity on a men’s body-positivity Tumblr blog called Body Positivity for Guys. | Instrumental case study collection of visual and textual data from BPfG | Hegemonic Masculinity &Inclusive Masculinity | Male or masculine-identifying BPfG members | Acceptance of diversity, sexuality, race,

gender Rejection of homophobia and misogyny Emotional vulnerability |

8/10 a | |

| Drummond et al. (2014) | Australia university |

To examine if the cultural shift in homosocial intimacy is evident among Australian undergraduate men. | Qualitative Questionnaire | Inclusive Masculinity | 90 | Heterosexual undergraduate men 18- to 25-year-old |

Decreased levels of homophobia Homosocial kissing |

8/10

a

8/9 b |

| Fine (2019) | USA -online | To examine how the McElroy brothers are exemplars of how nerds, queer, contemporary masculinity discourse | Qualitative Thematic Analysis |

Nerd masculinity | 41 episodes | McElroy brothers—2 podcasts | Rejection of traditional masculinity norms Eschew misogyny, homophobia and transphobia Emotional openness |

8/10 a |

| Finn and Henwood (2009) | UK Norfolk |

A psychosocial exploration of the identificatory positionings that are apparent in men’s talk of becoming first-time fathers. | Qualitative Interviews & focus groups |

Traditional & New masculinity | 30 | Heterosexual men aged between 18 and 40 | Rejection of traditional fatherhood role and

norms Caring Involved Emotionally connected |

7/10 a |

| Gottzén & Kremer-Sadlick (2012) | USA Los Angeles |

Examines how men juggle two contrasting cultural models of

masculinity when fathering through sports—a performance-oriented orthodox masculinity that historically has been associated with sports and a caring, inclusive masculinity that promotes the nurturing of one’s children. |

Ethnography Video of family activities (4 day) Semi-structured interviews |

Orthodox Masculinity & Inclusive Masculinity |

30 | Heterosexual families Middleclass families, both parents work, 2–3 children, pay mortgage on own home |

Caring Involved Emotionally connected Less traditional ways of fathering |

7/10 a |

| Greenebaum & Dexter (2018) | USA | This research explores how 20 vegan men explain veganism in relation to patriarchal, hegemonic masculinity. | Grounded theory interviews | Hybrid Masculinity | 20 | Males 21–76 years old Median age 39.5 |

Rejection of sexist attitudes and traditional masculine

stereotypes Compassion Caring |

7/10 a |

| Hall et al. (2012) | UK MacRumors website |

To study an internet forum, using membership categorization analysis (Sacks 1972; 1992) to investigate the deployment of metrosexuality and related identity categories. | Membership Categorization Analysis (MCA) Analysis of text |

Metrosexuality | Forum members, identifying as male | Rejecting traditional masculine norms Adopting interest in looks, grooming, clothes Metrosexual |

8/10 a | |

| Henwood & Procter (2003) | UK Norfolk |

Investigates men’s responses to contemporary sociocultural transformations in masculinity and fatherhood, and revised expectations of them as fathers. | Qualitative Semi-structured Interviews | Traditional Masculinity & New masculinity |

30 | Men aged 18–35 | Putting children first Presence, involvement Nurturing, caring |

7/10 |

| Jarvis (2013) | UK | To explore the relationship between straight men joining gay teams in a context of changing masculinities | Qualitative Interviews | New masculinities | 12 | Diverse range of self-identified straight men living in the UK, | Shifting attitudes toward homosexuality Rejection of traditional masculinity norms |

7/10 a |

| Jóhannsdóttir & Gíslason (2018) | Iceland | To explore young men’s perceptions of new masculinities | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews | New & Inclusive Masculinity | 9 | Males 18–25 years old (no children) | Dissatisfaction with restrictions imposed by traditional

masculinity norms Decreasing homophobia, misogyny Changing gender roles, Emotional and physical intimacy with same sex friends Caring Freedom of choice |

7/10 a |

| Johansson (2011) | Sweden | To explore how men, think, communicate and reason on fatherhood and parenthood | Qualitative In depth interviews and case studies |

New masculinities | 4 | Men who split paternity leave with their spouse | Rejection of traditional fatherhood role/gender

roles Prioritize family, intimate relationships and emotional experiences Seek work/family balance |

7/10 a |

| Lee & Lee (2018) | USA | To examine stay at home fathers lived experiences through the perspective of the theory of caring masculinities | Grounded Theory Semi structured interviews |

Caring masculinity | 25 | Stay at Home fathers | Rejecting traditional masculinity/gender roles Embracing affective, relational and emotional qualities of care Hands on care giving |

7/10 a |

| Magrath & Scoats (2019) | England | To explore if men described as exhibiting inclusive

masculinities at university continue to do so—and to what degree—as they enter the workplace and develop family ties. |

Qualitative Semi-structured interviews | Inclusive Masculinity | 10 | Men, now aged 28–31, who participated in a previous study by Anderson, E (2009) | Emotional intimacy Pro-gay Physical intimacy less than when at university Re-affirming of previous rejection of traditional norms Thus, this research contributes to IMT as it offers preliminary analysis into the friendships of inclusive men, after their time at university. |

8/10 a |

| McCormack (2011) | UK Secondary school |

Examines how boys’ masculinities are predicated in opposition to the orthodox values of homophobia, misogyny, and aggressiveness. | Ethnography Participant observation In-depth interviews observation |

Inclusive masculinity theory | 12 | 16- to 18-year-old males in school Upper middle class |

Rejection of homophobia, misogyny and

aggression Emotional support of peers. |

10/10 a |

| McCormack (2014) | UK Secondary school |

Examines the emergence of progressive attitudes toward homosexuality among working-class boys in a sixth form in the south of England | Ethnography Participant observation In-depth interviews |

Inclusive masculinity theory | 10 | Males in 6th form at a school in working class area | Decreased levels of homophobia Homosocial tactility Valuing of friendship Emotional closeness However, these behaviors are less pronounced than documented among middle-class boys, |

9/10 a |

| Morales & Caffyn-Parsons (2017) | USA High school |

To describe and explicate modern adolescents

gendered behavior, |

Ethnography Participant and non-participant observation In-depth interviews |

Inclusive masculinity theory | 10 | 16–17-year-old males Heterosexual Cross country runners |

Absence of homophobia Homosocial tactility Emotional intimacy Non-violent conflict management |

9/10 a |

| Morris & Anderson (2015) | Britain | To examine how (these) young men developed and exhibit their inclusive masculinities an attitude’s which we postulate are a reflection of dominant youth culture | Qualitative Interpretive video analysis and 1 in-depth interview |

Inclusive Masculinity | Britain’s top 4 male vloggers | Rejection of traditional masculinity norms Association with homosexuality and femininity Displays of homosocial tactility Pro-gay discourse vulnerability |

7/10 a | |

| Pfaffendorf (2017) | USA | Examines how privileged young men in Western TBS program for substance abuse construct hybrid masculinities to navigate masculinity dilemmas that arise in the therapeutic context | Ethnography In depth interviews |

Hybrid Masculinity | 34 | School alumni and staff who were 18 or older | Distancing from traditional hegemony Decreased levels of homophobia Sensitive of others Caring |

10/10 a |

| Roberts (2018) | England | To examine data from a qualitative, longitudinal study of English young men’s negotiation and performance of masculinity during their transitions to adulthood. | Digital

Ethnography Longitudinal Interviews Digital observation |

Inclusive masculinity theory | 24 | 18–24-year-old males | Rejection of traditional masculinity norms Shifting of gendered ‘work’ roles. |

8/10 a |

| Roberts et al. (2017) | England | To investigate the performances and understandings of masculinity in relation to decreasing homo-hysteria. | Ethnography Interviews Observation |

Inclusive masculinity theory | 22 | Elite level soccer players 16–18 years old Heterosexual Working class |

Decreased levels of homophobia Emotional closeness Physical contact |

7/10 a |

| Robinson et al. (2018) | UK university | The present study provides the first known qualitative examination of heterosexual undergraduate men’s conceptualization and experiences of the bromance, outside research on cinematic representations | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews |

Inclusive masculinity theory | 30 | Undergraduate men enrolled in 4 undergraduate sport-degree

programs at one university in the UK Middle class |

Decreased levels of homophobia Emotionally intimate Physically demonstrative trust |

10/10 a |

| Scoats (2017) | Britain | To determine if heterosexual men’s online identities encompassed a more inclusive style of masculinity, compared with previously dominant orthodox constructions. | Qualitative Summative content analysis |

Inclusive Masculinity | 44 | Heterosexual, white, males 18–20 years old attending university sports course | homosocial tactility, dancing with and kissing other

men distancing from orthodox masculine archetypes. Altered gendered behavior patterns |

8/10 a |

| White & Hobson (2017) | UK Secondary schools |

To establish how PE teachers, understand and construct masculinities within the educational environment. | Qualitative in-depth interviews |

Inclusive masculinity theory | 17 | English male PE teachers | Emotionally open Embracing more effeminate clothing Increasingly physically tactile |

7/10 a |

JBI Critical appraisal checklist for Qualitative research score.

JBI Critical appraisal checklist for Prevalence score.

Data Extraction

Data extraction was undertaken by the first author using a template that included the following domains (a) Author/s and year of publication, (b) country of study and setting, (c) aim of the study, (d) study design, (e) study methods, (f) theoretical background, (g) sample size, (h) population, and (i) and results.

Data Syntheses

Synthesis of the data was undertaken using thematic analysis. The first author undertook the thematic analysis, and this was reviewed by co-authors.

Thematic analysis is a systematic multistage process requiring the author to continually revisit the data. In the first phase of thematic analysis the author is required to read the articles identifying recurring elements in each. These elements were then reviewed for commonalities between them and clustered into larger groups called concepts. The concepts represent the underlying abstract ideology of the data. Finally, the concepts were further grouped into Global Themes. Global Themes encompass both the recurring themes and concepts and represent a single idea that has been identified in, and is supported by, the data (Attride-Stirling, 2001; Parahoo, 2006). Four global themes were identified within the data: (a) Inclusivity, (b) Emotional Intimacy, (c3) Physicality, and (d) Resistance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Recurring Elements, Concepts, and Global Themes.

| Recurring elements | Concepts | Global themes |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased levels of homophobia Absence of homophobia Rejection/contestation homophobia Shifting attitudes toward homosexuality |

Acceptance of differing sexualities | Inclusivity |

| Acceptance of gender diversity | Acceptance of differing genders | |

| Respect for women Rejection of traditional gender roles Rejection of misogyny |

Acceptance of women | |

| Sensitive of others Rejection of racism |

Acceptance of differing races | |

| Emotional bonding Emotional closeness Emotional sharing |

Emotional bonding | Emotional Intimacy |

| Increased emotional support between

friends Trust Vulnerability Compassion |

Emotional openness | |

| Developing intimate

relationships Presence Prioritizing of intimate relationships |

Emotional growth | |

| Hugging Cuddling Kissing |

Intentional physical contact | Physicality |

| Increasing physical tactile Physical intimacy with same sex friends |

Adoption of physical intimacy | |

| Dancing with men | Open displays of physical connectedness | |

| Metrosexual Bromance |

Hybrid masculinities | Resistance |

| Rejection of orthodox masculinities Rejection of traditional masculinity norms |

Rejection of traditional/orthodox masculinity | |

| Decrease in hyper-masculine behavior Avoidance of fights and violence Decreased levels risk taking |

Rejection of traditional masculine stereotypes | |

| Caring and connecting Less traditional ways of fathering Seek work/family balance |

Rejection of traditional masculine norms |

Results

While the search criteria included studies from 1990, all 33 articles in this systematic review, that met the inclusion criteria, are post 2000, with only four being published before 2010 (Anderson, 2005, 2008; Finn & Henwood, 2009; Henwood & Procter, 2003).

From the 33 articles, the profile of the participants included men from middle-class backgrounds, aged between 16 and 25 years (n = 19; 57.6%), men from middle-class backgrounds aged between 18 and 76 years (n = 3; 9.1%), men from working-class background aged between 16 and 19 years (n = 1; 3%), and men where details of class and age were not provided (n = 10; 30.3%).

Fourteen (42.4%) of the participant cohorts self-identified as heterosexual, the remainder of the studies (57.6%) did not specify participant sexual preference.

The majority of the 33 studies were undertaken in either sporting (n = 10; 30.3%) or educational settings such as high schools or universities (n = 8; 24.2%) with the remainder being undertaken with fathers (n = 6; 18.2%), through online blogs and podcasts (n = 5; 15.2%) or in non-specific settings (n = 4; 12.1%). Table 2 provides details of all studies included. Global themes identified will be discussed within the context of each setting.

Inclusivity

The Global Theme of Inclusivity relates to the participants’ acceptance of homosexuality, decreasing levels of homophobia, as well as decreasing levels of misogyny, and a general desire for gender equality. Twenty-four of the 33 studies reported that the participants displayed decreased levels of homophobia (Adams, 2011; Anderson, 2008, 2011, 2012; Anderson et al., 2019; Anderson & McCormack, 2015; Anderson & McGuire, 2010; Blanchard et al., 2017; Caruso & Roberts, 2018; Drummond et al., 2014; Fine, 2019; Hall et al., 2012; Jarvis, 2013; Jóhannsdóttir & Gíslason, 2018; Magrath & Scoats, 2019; McCormack, 2011, 2014; Morales & Caffyn-Parsons, 2017; Morris & Anderson, 2015; Pfaffendorf, 2017; Roberts et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2018; Scoats, 2017; White & Hobson, 2017). This ranged from what was described as shifting attitudes toward homosexuality (Jarvis, 2013), to the complete absence of homophobia (Morales & Caffyn-Parsons, 2017).

Jarvis (2013), identified that while their heterosexual participants were open to participating in sport alongside gay men, some still adhered to traditional masculinity norms and found subtle ways to assert their heterosexuality. Jarvis (2013) acknowledges that while the participants in his study happily joined gay sporting clubs, most ensured that the members were aware of their heterosexuality, one even bringing his girlfriend to a match as evidence.

Morales and Caffyn-Parsons (2017), in their study of 16 and 17-year-old cross-country runners in the United States identified a complete lack of homophobia among the participants.

Seventeen of the 24 studies examining homophobia also indicated that the participants not only rejected homophobia, they also rejected misogyny and advocated for gender equality (Anderson, 2005, 2008; Anderson & McGuire, 2010; Brandth & Kvande, 2018; Caruso & Roberts, 2018; Fine, 2019; Finn & Henwood, 2009; Gottzén & Kremer-Sadlick, 2012; Greenebaum & Dexter, 2018; Hall et al., 2012; Jóhannsdóttir & Gíslason, 2018; Johansson, 2011; Lee & Lee, 2018; Magrath & Scoats, 2019; McCormack, 2011; Morris & Anderson, 2015; Roberts, 2018).

The fathers in the study by Brandth and Kvande (2018) demonstrated inclusivity by undertaking what is traditionally considered to be women’s work, such as laundry, cooking, and child care. Most participants asserted that this is not even to be questioned, and such tasks are now “taken for granted competence” in men. Johansson (2011) and Lee and Lee (2018) both demonstrated their participants’ desire to father in gender-equal relationships with their partners. Three studies set in the online space, Caruso and Roberts (2018), Fine (2019), and Morris and Anderson (2015), identified that their participants regularly discussed topics such as gender inequity and actively rejected misogyny and homophobia.

Emotional Intimacy

The global theme of Emotional Intimacy relates to the participants sharing their intimate feelings and displaying their emotions with their male friends. This level of emotional vulnerability is in direct contrast to traditional masculinity norms that require men to be stoic and resist sharing feelings and emotions, particularly with another man (Courtenay, 2000).

Emotional intimacy was identified in 23 of the studies (Adams, 2011; Anderson, 2008, 2011, 2012; Anderson & McGuire, 2010; Blanchard et al., 2017; Brandth & Kvande, 2018; Caruso & Roberts, 2018; Fine, 2019; Finn & Henwood, 2009; Gottzén & Kremer-Sadlick, 2012; Henwood & Procter, 2003; Jóhannsdóttir & Gíslason, 2018; Johansson, 2011; Lee & Lee, 2018; Magrath & Scoats, 2019; McCormack, 2011; McCormack, 2014; Morales & Caffyn-Parsons, 2017; Morris & Anderson, 2015; Roberts et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2018; White & Hobson, 2017).

Anderson (2011) described participants hugging and comforting each other openly when sad or upset. Anderson & McGuire (2010) describe their rugby players as reporting that they support each other when the coaches give them a hard time, again reporting that they are “there for each other.” Likewise, the 16 to 18-year-old men in McCormack’s (2011, 2014) studies expressed their feelings freely and openly with their man friends.

In the studies focused on fatherhood, the element of emotional intimacy was in relation to their children rather than with a man friend. Johansson (2011) reports that the first-time fathers in this Swedish study prioritized intimate relations, family life, and emotional experiences. In addition, they wanted to find a balance between work and family life.

The study of a men’s online body blog by Caruso and Roberts (2018) identified that the men users shared vulnerability with each other on topics such as, but not limited to, body image and sexuality. The McElroy brothers in Fine’s (2019) study demonstrate emotional intimacy to their audience through authentic dialogue. Similarly, Morris and Anderson (2015) demonstrated that Charlie, the vlogger in their study, achieved emotional intimacy with his audience through authentic sharing of himself.

The global theme of emotional intimacy was also reported by both Jóhannsdóttir and Gíslason (2018) and Magrath and Scoats (2019). The young Icelandic men in the study by Jóhannsdóttir and Gíslason (2018) reported that they were able to talk to their man friends not just about what they did but also about how they felt. They describe these friendships as caring and their man friends as emotional support.

Physicality

The global theme of physicality refers to the participants demonstrating increased levels of intentional touching. Fourteen studies (42.4%) reported this theme; however, it was more evident in sporting settings (Adams, 2011; Anderson, 2011; Anderson & McCormack, 2015; Morales & Caffyn-Parsons, 2017; Roberts et al., 2017) and educational settings (Anderson et al., 2019; Blanchard et al., 2017; Drummond et al., 2014; McCormack, 2014; Robinson et al., 2018; White & Hobson, 2017). However, there was evidence of increased levels of intentional touching in other settings (Brandth & Kvande, 2018; Magrath & Scoats, 2019; Scoats, 2017).

Morales and Caffyn-Parson’s (2017) results indicated that the participants regularly hugged and touched each other affectionately. They described their hugs as “a full embrace” or “full frontal,” rather than a “brief hug and two strong pats on the back.” It was observed that participation in these behaviors was open and without fear of rejection. The participants in this American study declared that kissing was not a way that they would normally show affection to their man friends but that did not mean that they would not do it. Adams (2011), Anderson (2011), and Roberts et al. (2017), all report high levels of physical closeness within their participant groups. Hugging for an extended period is the most common behavior, but sharing beds, leaning up against each other, and touching face, and hair occurs regularly. Importantly these behaviors were performed openly with the authenticity of feeling.

The studies of Drummond et al. (2014) and Anderson et al. (2019) aimed to explore the frequency, context, and meanings of same-sex kissing among university men aged 18 to 25 years in Australia and the United States.

Both studies reported that same-sex kissing occurred among the participants, but it is contextualized within close friendship groups, during sport, or when alcohol is consumed. Most participants indicated that kissing another male was fine for heterosexuals in certain circumstances, such as, if it followed scoring a goal, or during a night out in a public place. Participants who did not engage in same-sex kissing revealed this act was associated with being gay, indicating that there is still social pressure in some young men to assert their heterosexual identity, in line with traditional masculinity norms.

Resistance

The global theme of resistance refers to the participants’ rejection of orthodox masculinity and traditional masculinity norms. Of the 33 studies included in the systematic review, only three did not demonstrate this (Anderson, 2011; Anderson & McCormack, 2015; Roberts et al., 2017).

The male cheerleaders in Anderson (2005) were not concerned about being considered “gay” by other men. They also had no concerns undertaking traditional women’s roles within their sport, questioning the need for gender roles at all. These findings were also supported by Morales and Caffyn-Parsons (2017) and Anderson and McGuire (2010).

Anderson’s (2011) study on American soccer players provided evidence that these participants were “eschewing violence” (p. 736). Indeed, of the 22 participants, most reported that they had never been in a fight and did not see the sense in it. An earlier study by Anderson (2012), among high school students, similarly demonstrated these participants rejected violence. The school disciplinary record indicated that there were no physical altercations between any students during the school year.

McCormack (2011, 2014), and Pfaffendorf (2017) reported evidence of rejection of aggression and violence in their studies on boys in education settings.

In the context of the fatherhood-focused studies, resistance was related to rejection of orthodox masculinity stereotypes and finding non-traditional ways of fathering, which included valuing positive emotions and taking pride in their caregiving role (Johansson, 2011; Lee & Lee, 2018).

The men in Magrath and Scoats (2019) reaffirm their rejection of orthodox masculinity norms by continuing to support each other in a caring and vulnerable way. Jóhannsdóttir and Gíslason (2018) report that the young men in their study are moving away from the stereotypical and traditional notions of masculinity. The vegan men in Greenbaum and Dexter (2018) embrace typically feminine traits such as compassion and empathy which is the antithesis of orthodox masculinity.

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to synthesize the existing empirical research on contemporary masculinities and conceptualize how men perceive and interpret these new masculinities. From the literature, four key concepts that seem integral to the understanding and performance of contemporary masculinities were identified: (a) Inclusivity, (b) Emotional Intimacy, (c) Physicality, and (d) Resistance. These concepts can be used to better understand men’s perceptions of contemporary masculinities and to construct new measurement tools to assess the performance of contemporary masculinities which in turn can inform program and policy development.

Much of the research reviewed, 24 of the 33 articles, were undertaken by scholars using Inclusive Masculinity as the Theoretical background for their studies. It is therefore not surprising that this review identified males’ understanding of contemporary masculinities to include decreased levels of homohysteria, and increased physical intimacy as this is consistent with IMT (Anderson, 2009). While not negating the findings of this review, this does suggest that there is limited empirical research being undertaken on contemporary masculinities.

The majority of participants in the studies reviewed were middle-class men between the ages of 16 and 25. The question needs to be asked, are the elements of inclusivity, emotional intimacy, physicality, and resistance, identified in this review, a result of intentional masculinity behavior changes. or are they a generational reaction to the current discourse around changing masculinity (Elliott, 2019; Ralph & Roberts, 2020)? The participants’ profile suggests that these young men are privileged and already have the balance of power required to be able to choose how to perform their masculinity (Bridges & Pascoe, 2018; Connell, 1995).

While there is clear evidence in these studies of behavior change in young men, there is also conflicting evidence to indicate that these same young men are still adhering to some of the traditional masculinity norms such as portraying a heterosexual identity with its inherent power over “others” (Bridges & Pascoe, 2018; Connell, 1987, 1995; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). The participants appear to be accepting of differences in sexuality but many still assert their hetero status.

The synthesized findings indicate that young, middle-class, heterosexual men in Western cultures, while still demonstrating some traditional masculinity norms, appear to be adopting some aspects of contemporary masculinities. The scholars of contemporary masculinity theories suggest that this has several benefits. Acceptance of others, including those of differing genders and sexualities, contributes to decreasing levels of violence (Anderson et al., 2019). Increased acceptance of women as equals assists in breaking down the unequal power relations between men and women and contributes to a more gender-equal society (McCormack, 2011). For men themselves, having the freedom to be open with feelings and emotions and to be able to show vulnerability, has a direct positive effect on their mental health and well-being (Anderson, 2011; Anderson & McGuire, 2005; Peretz et al., 2018). In addition, increased emotional and physical contact with others including other men contributes to more positive relationships, which benefits society (Brandth & Kvande, 2018; Henwood & Procter, 2003; Peretz et al., 2018). Future research into contemporary masculinities would benefit by including more diverse socio-economic groups and being undertaken in more diverse spaces.

Limitations

A significant limitation to this study is the exclusion of non-peer-reviewed published empirical research studies. This criteria appear to have privileged the work of Anderson and scholars of IMT. A significant number of articles by scholars other than Anderson were excluded from the review as they were books, discussion papers, theoretical papers, or book chapters. Contemporary masculinity research may benefit from scholars aiming to publish more peer-reviewed empirical research to solidify the field in wider academic circles.

A further limitation was the exclusion of studies that were not done in Western high-income countries or were not in English. As the construct of masculinity is defined by specific cultural behaviors and practices, limiting this review to Western countries was designed to ensure a consistent understanding of the concept of masculinity. It is acknowledged that there is a vast amount of research from non-English speaking and non-Western countries and there is a need for research to summarize how contemporary masculinities are understood and described in these contexts.

Conclusion

This systematic review aimed to synthesize the existing research on contemporary masculinities and to conceptualize how they are understood and interpreted by men in the literature. The review identified four concepts that are evident in the performance of contemporary masculinities. The concepts, (a) Inclusivity, (b) Emotional Intimacy, (c) Physicality, and (d) Resistance, provide an increased recognition and understanding of how contemporary masculinities are being performed and how young men can challenge orthodox masculinities and traditional manly stereotypes.

These elements are not intended to be a concrete measure of contemporary masculinities, nor is this new knowledge. It is, however, a synthesis of the existing knowledge, particularly, Inclusive Masculinity Theory and Hybrid Masculinity. The elements do provide a framework that demonstrates the differences between the behaviors of new and contemporary masculinities and the behaviors of orthodox masculinities.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: First author undertook the literature search supported by second and third authors. All three authors participated in screening of records in Covidence, with all records screened by first author and second and third authors screening half the records each in the role of second reviewer. First author conducted the analyses in collaboration with second and third authors. First author drafted the manuscript and, all authors contributed to ongoing revisions of the manuscript and approved of definitive version. All authors accept responsibility for submitted manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Ethics approval was not required for this systematic review.

Consent for Publication: “Not applicable.”

ORCID iD: Sandra Connor  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8511-5100

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8511-5100

Availability of Data and Material: The data sets used to support the conclusions of this article are included as tables in the Results section.

References

- Adams A. (2011). “Josh wears pink cleats”: Inclusive masculinity on the soccer field. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(5), 579–596. 10.1080/00918369.2011.563654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. (2005). Orthodox and inclusive masculinity, competing masculinities among heterosexual men in a feminized terrain. Sociological Perspectives, 48(3), 337–355. https://doi.org/org/10.1525/sop.2005.48.3.337 [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. (2008). Inclusive masculinity in a fraternal setting. Men and Masculinities, 10(5), 604–620. 10.1177/1097184X06291907 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. (2009). Inclusive masculinity: The changing nature of masculinities. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. (2011). Inclusive masculinities of university soccer players in the American Midwest. Gender and Education, 23(6), 729–744. 10.1080/09540253.2010.528377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. (2012). Inclusive Masculinity in a physical education setting. Journal of Boyhood Studies, 6(2), 151–165. 10.3149/thy.0602.151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E., McCormack M. (2015). Cuddling and spooning. Men and Masculinities, 18(2), 214–230. 10.1177/1097184x14523433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E., McCormack M. (2018). Inclusive masculinity theory: Overview, reflection and refinement. Journal of Gender Studies, 27(5), 547–561. 10.1080/09589236.2016.1245605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E., McGuire R. (2010). Inclusive masculinity theory and the gendered politics of men’s rugby. Journal of Gender Studies, 19(3), 249–261. 10.1080/09589236.2010.494341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E., Ripley M., McCormack M. (2019). A mixed-method study of same-sex kissing among college-attending heterosexual men in the US. Sexuality and Culture, 23(1), 26–44. 10.1007/s12119-018-9560-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arxer S. L. (2011). Hybrid masculine power: Reconceptualizing the relationship between homosociality and hegemonic masculinity. Humanity & Society, 35(4), 390–422. 10.1177/016059761103500404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Attride-Stirling J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytical tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. 10.1177/146879410100100307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barber K. (2016). Styling masculinity: Gender, class and inequality in the men’s grooming industry. Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bevens C. L., Loughnan S. (2019). Insights into men’s sexual aggression toward women: Dehumanization and objectification. Sex Roles, 81(11–12), 713–730. 10.1007/s11199-019-01024-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard C., McCormack M., Peterson G. (2017). Inclusive Masculinities in a working-class sixth form in Northeast England. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 46(3), 310–333. 10.1177/0891241615610381 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandth B., Kvande E. (2018). Masculinity and fathering alone during parental leave. Men and Masculinities, 21(1), 72–90. 10.1177/1097184x16652659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges T., Pascoe C. J. (2018). On the elasticity of gender hegemony: Why hybrid masculinities fail to undermine gender and sexual inequality. In Messerschmidt J. W., Martin P. Y., Messner M. A., Connell R. (Eds.), Gender reckonings (pp. 254–274). New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Britten A. (2001). Masculinities and masculinism. In Whitehead S. M., Barrett F. J. (Eds.), The masculinities reader (pp. 51–71). Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso A., Roberts S. (2018). Exploring constructions of masculinity on a men’s body-positivity blog. Journal of Sociology, 54(4), 627–646. 10.1177/1440783317740981 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W. (1987). Gender and power. Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W. (1995). Masculinities. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W., Messerschmidt J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender and Society, 19(6), 829–859. 10.1177/0891243205278639 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science Medicine, 50, 1385–1401. 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetriou D. (2001). Connell’s concept of hegemonic masculinity: A critique. Theory and Society, 30, 337–336. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond M. J. N., Filiault S. M., Anderson E., Jeffries D. (2014). Homosocial intimacy among Australian undergraduate men. Journal of Sociology, 51(3), 643–656. 10.1177/1440783313518251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott K. (2019). Negotiations between progressive and “traditional” expressions of masculinity among young Australian men. Journal of Sociology, 55(1), 108–123. 10.1077/1440783318802996 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fine L. E. (2019). The McElroy brothers, new media, and the queering of white nerd masculinity. Journal of Men’s Studies, 27(2), 131–148. 10.1177/1060826518795701 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finn M., Henwood K. (2009). Exploring masculinities within men’s identificatory imaginings of first-time fatherhood. British Journal of Psychology, 48(Pt 3), 547–562. 10.1348/014466608X386099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottzén L., Kremer-Sadlik T. (2012). Fatherhood and youth sports. Gender & Society, 26(4), 639–664. 10.1177/0891243212446370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum J., Dexter B. (2018). Vegan men and hybrid masculinity. Journal of Gender Studies, 27(6), 637–648. 10.1080/09589236.2017.1287064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M., Gough B., Seymour-Smith S., Hansen S. (2012). On-line constructions of metrosexuality and masculinities: A membership categorization analysis. Gender and Language, 6(2), 379–403. 10.1558/genl.v6i2.379 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henwood K., Procter J. (2003). The ‘good father’: Reading men’s accounts of paternal involvement during the transition to first-time fatherhood. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42(3), 337–355. 10.1348/01446660332243819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughson J. (2000). The boys are back in town: Soccer support and the social reproduction of masculinity. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 24(1), 8–23. 10.1177/0193723500241002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis N. (2013). The inclusive masculinities of heterosexual men within UK gay sport clubs. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50(3), 283–300. 10.1177/1012690213482481 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. (2017. a). Critical appraisal checklist for prevalence studies. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. (2017. b). Critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

- Jóhannsdóttir Á., Gíslason I. V. (2018). Young Icelandic men’s perception of masculinities. Journal of Men’s Studies, 26(1), 3–19. 10.1177/1060826517711161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson T. (2011). Fatherhood in transition: Paternity leave and changing masculinities. Journal of Family Communication, 11(3), 165–180. 10.1080/15267431.2011.561137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Y., Lee S. J. (2018). Caring is masculine: Stay-at-home fathers and masculine identity. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 19(1), 47–58. 10.1037/men0000079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magrath R., Scoats R. (2019). Young men’s friendships: Inclusive masculinities in a post-university setting. Journal of Gender Studies, 28(1), 45–56. 10.1080/09589236.2017.1388220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik J. R., Walker G., Levi-Minzi M. (2007). Masculinity and health behaviors in Australian men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 8(4), 240–249. 10.1037/1524-9220.8.4.240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack M. (2011). Hierarchy without Hegemony: Locating boys in an inclusive school setting. Sociological Perspectives, 54(1), 83–101. 10.1525/sop.2011.54.1.83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack M. (2014). The intersection of youth masculinities, decreasing homophobia and class: An ethnography. British Journal of Sociology, 65(1), 130–149. 10.1111/1468-4446.12055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messerschmidt J. W., Messner M. A. (2018). Hegemonic, nonhegemonic, and “new” masculinities. In Messerschmidt J. W., Martin P. Y., Messner M. A., Connell R. (Eds.), Gender reckonings (pp. 35–56). New York University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1pwtb3r.7 [Google Scholar]

- Messner M. (1992). Power at play: Sports and the problem of masculinity. Beacon. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), Article e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales L. E., Caffyn-Parsons E. (2017). “I love you, guys”: A study of inclusive masculinities among high school cross-country runners. Boyhood Studies-An Interdisciplinary Journal, 10(1), 66–87. 10.3167/bhs.2017.100105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M., Anderson E. (2015). ‘Charlie is so cool like’: Authenticity, popularity and inclusive masculinity on YouTube. Sociology, 49(6), 1200–1217. 10.1177/0038038514562852 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parahoo K. (2006). Nursing research principles, process and issues (2nd ed). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Peretz T., Lehrer J., Dworkin S. L. (2018). Impacts of men’s gender-transformative personal narratives: A qualitative evaluation of the Men’s story project. Men and Masculinities, 23(1), 104–126. 10.1177/1097184X18780945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffendorf J. (2017). Sensitive cowboys: Privileged young men and the mobilization of Hybrid Masculinities in a therapeutic boarding school. Gender & Society, 31(2), 197–222. 10.1177/0891243217694823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph B., Roberts S. (2020). One small step for man: Change and continuity in perceptions and enactments of homosocial intimacy among young Australian men. Men and Masculinities, 21(1), 83–103. 10.1177/1097184X18777776 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S. (2018). Domestic labour, masculinity and social change: Insights from working-class young men’s transitions to adulthood. Journal of Gender Studies, 27(3), 274–287. 10.1080/09589236.2017.1391688 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S., Anderson E., Magrath R. (2017). Continuity change and complexity in the performance of masculinity among elite young footballers in England. British Journal of Sociology, 68(2), 336–357. 10.1111/1468-4446.12237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S., Anderson E., White A. (2018). The Bromance: Undergraduate male friendships and the expansion of contemporary homosocial boundaries. Sex Roles, 78(1–2), 94–106. https://doi.org/0.1007/s11199-017-0768-5 [Google Scholar]

- Scoats R. (2017). Inclusive masculinity and Facebook photographs among early emerging adults at a British university. Journal of Adolescent Research, 32(3), 323–345. 10.1177/0743558415607059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S., Inhorn M. C. (2016). Emergent masculinities, men’s health and the Movember movement. In Gideon J. (Ed.), Handbook on gender & health (pp. 436–456). Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Waling A. (2020). White masculinity in contemporary Australia: The good Ol’ Aussie Bloke. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- White A., Hobson M. (2017). Teachers’ stories: Physical education teachers’ constructions and experiences of masculinity within secondary school physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 22(8), 905–918. 10.1080/13573322.2015.1112779 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead S. M., Barrett F. J. (2001). The sociology of masculinity. In Whitehead S. M., Barrett F. J. (Eds.), The masculinities reader (pp. 1–26). Polity Press. [Google Scholar]