Abstract

PARP-1 and ATM are both involved in the response to DNA strand breaks, resulting in induction of a signaling network responsible for DNA surveillance, cellular recovery, and cell survival. ATM interacts with double-strand break repair pathways and induces signals resulting in the control of the cell cycle-coupled checkpoints. PARP-1 acts as a DNA break sensor in the base excision repair pathway of DNA. Mice with mutations inactivating either protein show radiosensitivity and high radiation-induced chromosomal aberration frequencies. Embryos carrying double mutations of both PARP-1 and Atm genes were generated. These mutant embryos show apoptosis in the embryo but not in extraembryonic tissues and die at embryonic day 8.0, although extraembryonic tissues appear normal for up to 10.5 days of gestation. These results reveal a functional synergy between PARP-1 and ATM during a period of embryogenesis when cell cycle checkpoints are not active and the embryo is particularly sensitive to DNA damage. These results suggest that ATM and PARP-1 have synergistic phenotypes due to the effects of these proteins on signaling DNA damage and/or on distinct pathways of DNA repair.

To survey the integrity of their genomes, eukaryotic cells have evolved a sophisticated network of proteins that play important roles in cell cycle regulation, stimulation of the DNA repair machinery, and alteration in the expression of genes necessary for the cell's recovery, survival, or apoptosis. Among these factors, PARP and ATM are both multidomain proteins with multiple cellular substrates that play a critical regulatory function in the coordination of the cellular processes of DNA repair and cell cycle checkpoint control.

The involvement of PARP-1 in the base excision repair (BER) pathway has been established in mice with genetic inactivation of PARP-1. Treatment of PARP-1−/− mice with either alkylating agents or γ-irradiation, both of which trigger the BER pathway, reveals an extreme sensitivity to and a high genomic instability in the presence of both of them. Treatment with alkylating agents, which activates PARP-1 in normal cells, causes PARP-1−/− splenocytes to undergo apoptosis extremely rapidly, with a stabilization of p53 (20). The extreme sensitivity of PARP-1−/− cells to these agents could be explained by the accumulation of unrepaired DNA damage. This view is supported by the fact that PARP-1−/− cells have a considerably prolonged delay of DNA strand break rejoining (3, 31). Whole-cell extracts from a PARP-deficient cell line are specifically defective in the polymerization step of the BER pathway (6, 7). In vivo, PARP-1 is strongly associated with XRCC1, a DNA repair protein linked to DNA polymerase β and DNA ligase III in the BER complex (19). Therefore, PARP-1 appears to play a key role in detecting DNA strand breaks and recruiting a DNA repair factor(s), allowing the cell to repair in a window of time compatible with cell cycle progression (24).

Ataxia telangiectasia (A-T) is a human autosomal recessive disorder characterized by a pleiotropic phenotype that includes progressive cerebellar degeneration, premature aging, cellular and humoral immune defects, growth retardation, telangiectasia, high sensitivity to ionizing radiation (IR), high incidence of cancer, and gonad atrophy. At the cellular level, A-T is characterized by chromosomal instability, radio-resistant DNA synthesis, hypersensitivity to IR (12, 27), and defects in recombinational repair (4, 22). In addition A-T cells grow slowly and exhibit defective induction at all checkpoints in response to DNA strand breaks. This may in part reflect the fact that A-T cells exhibit delayed induction of p53 in an IR-induced DNA damage-signaling pathway (14, 15, 34). The gene consistently mutated in A-T patients, Atm, belongs to the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase superfamily, a family of signal transduction proteins which possess a serine/threonine protein kinase activity (25, 35). Upon DNA damage, the ATM-p53-mediated checkpoint requires activated ATM, which in turn activates p53. Atm-deficient mice recapitulate the A-T phenotype in humans (2, 4, 8, 33): they are sterile and exquisitely sensitive to IR.

ATM also regulates pathways important for DNA repair. Cell lines established from Atm-deficient mice, like those from A-T patients, exhibit a defect in genomic stability as well as cell cycle checkpoint abnormalities after IR (2). BRCA1 and NBS1 are direct targets of ATM and participate directly in DNA repair pathways (5, 10, 11, 17, 32, 36). It is unclear which phenotypes in A-T patients or Atm-deficient mice are the result of defects in checkpoint function or DNA repair. The phenotypes of each of the single-mutant mice are likely attributed to the defect in sensing, repairing, or signaling DNA breaks. The mechanisms by which PARP-1 and ATM perform these various functions remain not totally characterized. We therefore investigated the relationship between PARP-1 and ATM in the whole animal. In this work, we show that the double mutation of both Atm and PARP-1 genes in the mouse leads to an early postimplantation lethality of the embryo at embryonic day 8.0 (E8.0), with extensive cell death in the embryo at E11.5. Since this period of embryogenesis is one of extreme sensitivity to DNA damage due to rapid proliferation and lack of checkpoints (13, 28), these results suggest that PARP-1 and ATM act synergistically in pathways that either monitor or repair DNA damage during mouse development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

PARP-1 and ATM single-mutant mouse lines have been described previously (2, 20). PARP-1−/− Atm−/− doubly null embryos were obtained by intercrosses of PARP-1−/− Atm+/− mice. Genotypes were determined by PCR on yolk sac DNA (primers and PCR conditions are available upon request).

Histological analysis.

Decidua were collected in 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2, and then fixed in Bouin's fluid for 14 h, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (6 μm thick) were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

PARP-1 and ATM are essential together for early embryonic development.

Mice heterozygous for Atm (2) were crossed with PARP-1−/− mice (20) to produce animals heterozygous for both mutations. Doubly heterozygous mice (PARP+/− Atm+/−) were interbred to generate null mice for both genotypes. No doubly homozygous mice were identified (not shown). PARP-1−/− Atm+/− mice were generated; they were viable and looked normal, but displayed an hypofertility phenotype (Table 1). PARP-1−/− Atm+/− mice were further intercrossed to generate doubly homozygous mutants, but genotype analysis at term (n = 123) failed to identify any animal of this genotype, whereas PARP-1−/− Atm+/+ and PARP-1−/− Atm+/− mice were recovered in a 1:2 ratio. Blastocysts (E3.5) were isolated from PARP-1−/− Atm+/− intercrosses by uterine flushing and then genotyped by PCR. Double-knockout (KO) embryos were detected at this stage, suggesting that deficiency of both PARP-1 and ATM resulted in early postimplantation embryonic lethality. Cumulative typing of litters at different stages of gestation demonstrated that double-KO embryos appeared up to E11.5 at a normal Mendelian ratio but displayed a severe retardation in their development.

TABLE 1.

Genotype analysis of PARP Atm embryos from heterozygous matings

| Intercross | Age of progeny | No. of pups/litter | n | No. of embryos (% of total) with Atm genotype:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | +/− | −/− | ||||

| PARP+/+Atm+/− | Newborn | 9.6 ± 0.7 | 77 | 28 (36) | 33 (43) | 16 (21) |

| PARP−/−Atm+/− | Newborn | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 123 | 30 (24) | 93 (76) | 0 |

| E14.5 | 31 | 8 (26) | 23 (74) | 0 | ||

| E8.0–E11.5 | 60 | 14 (24) | 29 (48) | 17 (28) | ||

PARP-1−/− Atm−/− embryos die by apoptosis shortly after the onset of gastrulation.

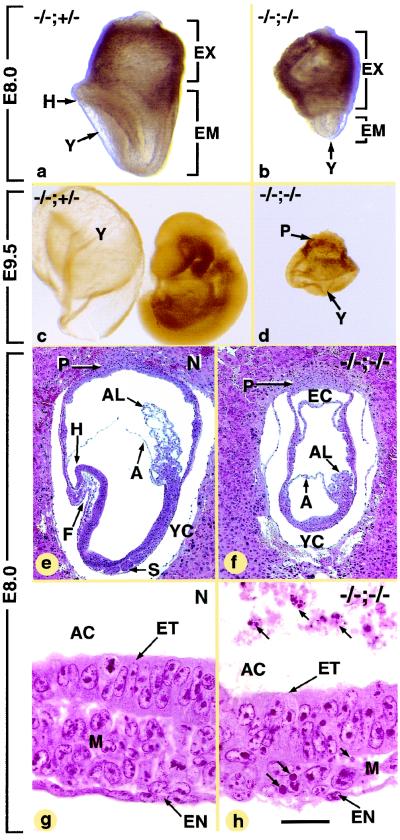

In order to determine the cause of the death of the double-null mutants, litters from PARP-1−/− Atm+/− intercrosses were analyzed at different developmental stages. The earliest defects were observed at E8.0. Normal E8.0 embryos (i.e., PARP-1−/− Atm+/+ and Atm+/− embryos) displayed prominent head folds (Fig. 1a and e), a foregut pocket (Fig. 1e), and somites (Fig. 1e). The five PARP-1−/− Atm−/− mutants genotyped at E8.0 were either severely growth retarded (compare Fig. 1a and b) or appeared as empty yolk sacs (data not shown; see below). Severely retarded E8.0 embryos analyzed on serial histological sections (n = 3) were arrested at a stage equivalent to E7.0, as they lacked head folds, a foregut pocket, and somites (Fig. 1f); had a persistent ectoplacental cavity (Fig. 1f); and already displayed a mesoderm (Fig. 1h) as well as a small allantois (compare Fig. 1e and f). However, these retarded embryos were markedly different from normal E7.0 embryos due to the presence of numerous pycnotic and fragmented nuclei, which were readily identifiable in the mesoderm and amniotic cavity (compare Fig. 1g and h).

FIG. 1.

External views and histological sections of E8.0 and E9.5 normal (N, not genotyped; PARP-1−/− Atm+/− [−/−;+/−]) and PARP-1 Atm double-null (−/−;−/−) conceptuses. The embryo in panel c was taken out of its yolk sac. Abbreviations: A, amnion; AC, amniotic cavity; AL, allantois; EC, ectoplacental cavity; EM, embryo; F, foregut pocket; H, head folds; P, placenta; S, somites; Y, yolk sac; YC, yolk sac cavity. Small arrows, condensed nuclear fragments. The same magnifications were used for panels a and b and for panels c and d. Scale bar (bar in panel h applies to panels e to h): 250 μm (e and f) and 25 μm (g and h).

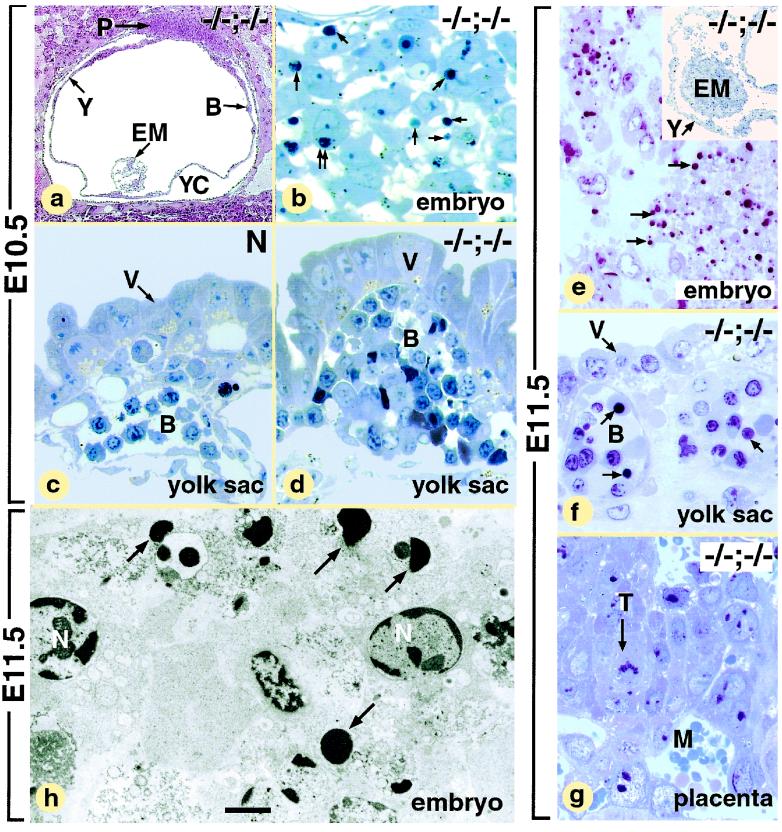

PARP-1−/− Atm−/− conceptuses genotyped at E9.5 (n = 4), E10.5 (n = 6), and E11.5 (n = 2) appeared as yolk sacs capped by the placenta (compare Fig. 1d with 1c; data not shown). At all these developmental stages, the embryonic tissues were replaced by a small mass of disorganized and loosely arranged cells (Fig. 2a and e) containing a large proportion of pycnotic and fragmented nuclei (about 30% at E10.5 [n = 2; Fig. 2b] and more than 90% at E11.5 [n = 1; Fig. 2e and h]). In contrast, the ectodermal and endodermal extraembryonic cells of the PARP-1−/− Atm−/− conceptuses, such as trophoblast cells (Fig. 2g) and parietal and visceral endodermal cells V (Fig. 2c, d, and f and data not shown), did not show apoptotic features. Along the same lines, numerous healthy primitive blood cells had differentiated within the extraembryonic mesoderm by E10.5 B (compare Fig. 2c and d). However, in E11.5 PARP-1−/− Atm−/− mutants, the primitive blood islands were scarce and contained numerous apoptotic cells (Fig. 2f).

FIG. 2.

Histological and electron-microscopic analysis of E10.5 and E11.5 normal mice (N) and presumptive PARP-1 Atm double-null mutants (−/−;−/−). Panels b and d represent high magnifications of areas similar to those designated in panel a by EM and Y, respectively. The inset in panel e is a low-magnification view of the embryo and yolk sac displayed in panels e and f. (b and d) Abnormal E10.5 embryos; (e to h) abnormal E11.5 embryos. Abbreviations: B, primitive blood islands; EM, embryo; M, maternal blood sinus; P, placenta; T, trophoblast cell; V, visceral endoderm; Y, visceral portion of the yolk sac; YC, yolk sac cavity. Arrows, condensed nuclear fragments; double arrow, phagocytosis of one of these fragments by an embryonic cell. Scale bar (bar in panel h applies to all panels): 280 μm (a), 15 μm (b), 20 μm (c and d to g), and 3 μm (h).

Altogether, these data indicate that PARP-1−/− Atm−/− embryonic tissues undergo apoptosis shortly after the onset of gastrulation and that cell types that do not directly participate in the formation of the embryo are relatively more resistant to the loss of both PARP-1 and ATM.

PARP-1 and Atm act in concert to preserve genomic integrity.

In mammals, during early postimplantation development, undifferentiated stem cells that form the epiblast sustain a high cell division rate (28). To ensure survival, a tight surveillance of genomic integrity is required. Recently, it has been shown that wild-type embryos exposed to low doses of X rays during gastrulation have a very low threshold for DNA damage (13). During this restrictive developmental window, embryonic cells undergo apoptosis without cell cycle arrest in response to a low dose of genotoxic stress. Interestingly, only embryonic cells become hypersensitive to DNA damage, not cells in the extraembryonic region. DNA damage might be tolerated in these cells because they are transient and do not give rise to critical lineages. Moreover, the same authors showed that low-dose irradiation during early gastrulation of Atm-deficient embryos does not induce an apoptotic response but that the embryos do not survive, demonstrating that (i) Atm is a key element in preventing the activation of apoptotic pathways and (ii) apoptosis is a safeguard mechanism to preserve genomic integrity during the development (13).

As seen in any proliferative state, intense metabolism in embryonic growth is accompanied by an oxidative burst that may cause oxidative damage to genomic DNA. In the double-mutant embryo both PARP-1- and ATM-mediated DNA repair and cell signaling of DNA damage were defective, leading to massive apoptosis of the embryo at the onset of gastrulation because of the dramatic sensitivity to DNA damage during this stage. That the extraembryonic tissue was less severely affected was likely due to a lower cell division rate or to lower susceptibility to apoptosis from persistent DNA damage, as shown in IR-treated embryos during gastrulation (13).

Interestingly, similar embryonic lethality phenotypes at the onset of gastrulation were observed in mutant embryos lacking BER factors, such as mutants lacking XRCC1 (30) and APE (REF) (18), two proteins acting at different steps in the BER pathway. APE and REF carry out repair incision at a basic site, allowing DNA polymerase β to synthesize a short patch of DNA (for a review see reference 26) which is ligated by DNA ligase I or III. XRCC1 is a scaffold protein linked to DNA polymerase β (16), DNA ligase III (23), and PARP (19). XRCC1 plays a key role as a stimulator of DNA ligase III (23) and as a negative regulator of PARP activity (19). All embryos suffered an overall developmental arrest at E7.5 to 8.5, whereas extraembryonic tissues appeared normal, suggesting that (i) these proteins are involved in the same pathway and (ii) the loss of ATM may exacerbate the BER deficiency in PARP-1−/− cells.

We and others have previously shown that BER occurs to some extent in PARP-1−/− cells but at a much lower rate than in wild-type cells (3, 6, 7, 31). PARP-1 is a member of a growing family of PARP proteins; among them, PARP-2 (1), another DNA damage-activated PARP, would likely functionally compensate for the lack of PARP-1. A gene-targeted deficiency of Polβ (29), encoding DNA polymerase β, resulted in lethality at E10.5, suggesting that other DNA polymerases (e.g., α and γ) have redundancy functions at least until midgestation. It is interesting that neither DNA glycosylase is necessary for development and survival in the mouse (reviewed in reference 9), suggesting redundancy of function between these enzymes. Then, a generalized deficiency of BER would likely be lethal because of spontaneous accumulation of DNA strand breaks and mutations.

BRCA1 and NBS1 are targets of ATM kinase activity (5, 10, 11, 17, 32, 36). BRCA1-deficient embryos display a lethal phenotype similar to that due to the BER proteins (9). ATM could play a role in regulating BRCA1 and NBS1 functions involved in multiple biological pathways that regulate cell cycle progression, centrosome duplication, DNA damage repair, and apoptosis. As noted above, homologous recombination is defective in Atm−/− cells (21) and mice (4). In consideration of these points, the synergistic phenotype displayed by PARP-1 Atm double mutants could be interpreted in two ways: ATM and PARP-1 participate in overlapping DNA damage signaling pathways and/or PARP-1 and Atm regulate distinct forms of DNA repair that partially compensate for each other. Since PARP-1 and ATM participate in BER and homologoous recombination, respectively, we favor the latter interpretation.

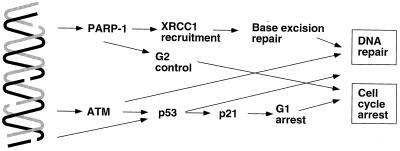

In conclusion, our results shed light on the consequence of the disruption of two important pathways for the surveillance of the genome during cell proliferation (Fig. 3) and identify PARP and ATM as “integrators” of signals emerging from DNA strand-breaks and suggest that a limited functional compensation is not excluded during cell proliferation since the loss of both pathways exacerbates the phenotype of loss of either pathway.

FIG. 3.

Signal transduction pathways leading to DNA repair and checkpoint induction by PARP-1 and Atm. PARP-1 is activated by breaks in DNA and is likely to recruit XRCC1 and the BER complex on the site of the lesion, allowing efficient DNA repair and cell cycle progression. ATM, a DNA double-stranded break enzyme, phosphorylates p53 specifically to selectively induce G1 arrest via p21 transcription.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to P. Chambon for his constant support, and to A. Huber, A. Gansmüller, and M. C. Hummel for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer, the Ligue contre le Cancer, Electricité de France, the Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique, and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ame J C, Rolli V, Schreiber V, Niedergang C, Apiou F, Decker P, Muller S, Hoger T, Menissier-de Murcia J, de Murcia G. PARP-2, a novel mammalian DNA damage-dependent poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17860–17868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlow C, Hirotsune S, Paylor R, Liyanage M, Eckhaus M, Collins F, Shiloh Y, Crawley J N, Ried T, Tagle D, Wynshaw-Boris A. Atm-deficient mice: a paradigm of ataxia telangectasia. Cell. 1996;86:159–171. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beneke R, Geisen C, Zevnik B, Bauch T, Muller W U, Kupper J H, Moroy T. DNA excision repair and DNA damage-induced apoptosis are linked to poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation but have different requirements for p53. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6695–6703. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6695-6703.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishop A J, Barlow C, Wynshaw-Boris A J, Schiestl R H. Atm deficiency causes an increased frequency of intrachromosomal homologous recombination in mice. Cancer Res. 2000;60:395–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortez D, Wang Y, Qin J, Elledge S J. Requirement of ATM-dependent phosphorylation of brca1 in the DNA damage response to double-strand breaks. Science. 1999;286:1162–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dantzer F, De La Rubia G, Menissier-de Murcia J, Hostomsky Z, de Murcia G, Schreiber V. Base excision repair is impaired in mammalian cells lacking poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7559–7569. doi: 10.1021/bi0003442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dantzer F, Schreiber V, Niedergang C, Trucco C, Flatter E, De La Rubia G, Oliver J, Rolli V, Menissier-de Murcia J, de Murcia G. Involvement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in base excision repair. Biochimie. 1999;81:69–75. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)80040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elson A, Wang Y, Daugherty C J, Morton C C, Zhou F, Campos-Torres J, Leder P. Pleiotropic defects in ataxia-telangiectasia protein-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13084–13089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedberg E C, Meira L B. Database of mouse strains carrying targeted mutations in genes affecting cellular responses to DNA damage: version 3. Mutat Res. 1999;433:69–87. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(98)00068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gatei M, Scott S P, Filippovitch I, Soronika N, Lavin M F, Weber B, Khanna K K. Role for ATM in DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of BRCA1. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3299–3304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gatei M, Young D, Cerosaletti K M, Desai-Mehta A, Spring K, Kozlov S, Lavin M F, Gatti R A, Concannon P, Khanna K. ATM-dependent phosphorylation of nibrin in response to radiation exposure. Nat Genet. 2000;25:115–119. doi: 10.1038/75508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halazonetis T D, Shiloh Y. Many faces of ATM: eighth international workshop on ataxia-telangiectasia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1424:R45–R55. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(99)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heyer B S, MacAuley A, Behrendtsen O, Werb Z. Hypersensitivity to DNA damage leads to increased apoptosis during early mouse development. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2072–2084. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kastan M B, Zhan Q, El-Deiry W S, Carrier F, Jacks T, Walsh W V, Plunkett B S, Vogelstein B, Fornace A J. A mammalian cell cycle checkpoint pathway utilizing p53 and GADD45 is defective in ataxia telangiectasia. Cell. 1992;71:587–598. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khanna K K, Lavin M F. Ionizing radiation and UV induction of p53 protein by different pathways in ataxia-telangiectasia cells. Oncogene. 1993;8:3307–3312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kubota Y, Nash R A, Klungland A, Schar P, Barnes D E, Lindahl T. Reconstitution of DNA base excision-repair with purified human proteins: interaction between DNA polymerase beta and the XRCC1 protein. EMBO J. 1996;15:6662–6670. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim D S, Kim S T, Xu B, Maser R S, Lin J, Petrini J H, Kastan M B. ATM phosphorylates p95/nbs1 in an S-phase checkpoint pathway. Nature. 2000;404:613–617. doi: 10.1038/35007091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ludwig D L, MacInnes M A, Takiguchi Y, Purtymun P E, Henrie M, Flannery M, Meneses J, Pedersen R A, Chen D J. A murine AP-endonuclease gene-targeted deficiency with post-implantation embryonic progression and ionizing radiation sensitivity. Mutat Res. 1998;409:17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(98)00039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masson M, Niedergang C, Schreiber V, Muller S, Menissier-de Murcia J, de Murcia G. XRCC1 is specifically associated with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and negatively regulates its activity following DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3563–3571. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ménissier-de Murcia J, Niedergang C, Trucco C, Ricoul M, Dutrillaux B, Mark M, Olivier F J, Masson M, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Walztinger C, Chambon P, de Murcia G. Requirement of poly(ADP-ribose)- polymerase in recovery from DNA damage in mice and in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7303–7307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison C, Sonoda E, Takao N, Shinohara A, Yamamoto K, Takeda S. The controlling role of ATM in homologous recombinational repair of DNA damage. EMBO J. 2000;19:463–471. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.3.463. . (Erratum, 19:786.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrison C, Wagner E. Extrachromosomal recombination occurs efficiently in cells defective in various DNA repair systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2053–2058. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.11.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nash R A, Caldecott K W, Barnes D E, Lindahl T. XRCC1 protein interacts with one of two distinct forms of DNA ligase III. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5207–5211. doi: 10.1021/bi962281m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliver F J, Menissier-de Murcia J, de Murcia G. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in the cellular response to DNA damage, apoptosis, and disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1282–1288. doi: 10.1086/302389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savitsky K, Bar Shira A, Gliad S, Rotman G, Ziv Y, Vnagaite L, Tagle D A. A single ataxia telangiectasia gene with a product similar to PI-3 kinase. Science. 1995;268:1749–1753. doi: 10.1126/science.7792600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seeberg E, Eide L, Bjoras M. The base excision repair pathway. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:391–397. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiloh Y. Ataxia-telangiectasia, ATM and genomic stability: maintaining a delicate balance. Two international workshops on ataxia-telangiectasia, related disorders and the ATM protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1378:R11–R18. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(98)00020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snow M H L. Gastrulation in the mouse: growth and regionalisation of the epiblast. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1977;42:293–303. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sobol R W, Horton J K, Kuhn R, Gu H, Singhal R K, Prasad R, Rajewsky K, Wilson S H. Requirement of mammalian DNA polymerase beta in base excision repair. Nature. 1996;379:183–186. doi: 10.1038/379183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tebbs R S, Flannery M L, Meneses J J, Hartmann A, Tucker J D, Thompson L H, Cleaver J E, Pedersen R A. Requirement for the Xrcc1 DNA base excision repair gene during early mouse development. Dev Biol. 1999;208:513–529. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trucco C, Oliver F J, de Murcia G, Menissier-de Murcia J. DNA repair defect in poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-deficient cell lines. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2644–2649. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.11.2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu X, Ranganathan V, Weisman D S, Heine W F, Ciccone D N, O'Neill T B, Crick K E, Pierce K A, Lane W S, Rathbun G, Livingston D M, Weaver D T. ATM phosphorylation of Nijmegen breakage syndrome protein is required in a DNA damage response. Nature. 2000;405:477–482. doi: 10.1038/35013089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y, Ashley T, Brainerd E E, Bronson R T, Meyn M S, Baltimore D. Targeted disruption of ATM leads to growth retardation, chromosomal fragmentation during meiosis, immune defects, and thymic lymphoma. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2411–2422. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu Y, Baltimore D. Dual roles of ATM in the cellular response to radiation and in cell control. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2401–2410. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zakian V A. ATM-related genes: what do they tell us about functions of the human gene? Cell. 1995;82:685–687. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao S, Weng Y C, Yuan S S, Lin Y T, Hsu H C, Lin S C, Gerbino E, Song M H, Zdzienicka M Z, Gatti R A, Shay J W, Ziv Y, Shiloh Y, Lee E Y. Functional link between ataxia-telangiectasia and Nijmegen breakage syndrome gene products. Nature. 2000;405:473–477. doi: 10.1038/35013083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]