Abstract

Purpose of Review

Suicide is a serious healthcare concern worldwide. In the USA, suicide was the tenth leading cause of death prior to 2020 when it was displaced as a result of the death toll from COVID-19.

Recent Findings

Suicide behavior is the result of the interaction between the individual’s predisposing factors and precipitating factors. A recognized precipitating factor is the knowledge of the suicidal act of another, termed suicide contagion. Another precipitating factor is the physiological impact of an acute inflammatory response to disease, for example that seen in patients with COVID-19.

Summary

Risk identification of persons at increased risk for suicidal actions is an essential goal in medical care so that protective measures can be employed to prevent suicide.

Keywords: Werther effect, Kabuki effect, Point cluster, Mass cluster, Suicide contagion

Introduction

Suicide has been estimated to be the tenth leading cause of death in the USA from 2015 through 2019, ranging from a low of 44,193 deaths in 2015 to a high of 49,344 deaths in 2018. In 2020 with the addition of COVID-19 as the third leading cause of death, suicide became the eleventh cause of death at 44,834 [1]. From 2007 and 2018, in the 10- to 24-years age group, the rate of suicide deaths increased by 57.4% making it the fourth cause of death in that age category [2]. The economic loss of one suicide has been estimated to be $1,329,553 of which 97% is attributed to loss of productivity and 3% to medical treatment [3]. The impact of an individual’s suicide extends beyond his family and close contacts into the local community and even beyond, depending on the scope, content, and audience of those receiving the information about the suicide death or attempt. As a major healthcare issue, it is important for those caring for these patients to have an understanding of why a patient chose suicide as a solution so that the provider can best support the patient who survived a suicide attempt and offer guidance to their family/significant others to prevent future suicidal behavior. When the patient dies, the healthcare provider can offer guidance and counsel to the decedent’s survivors who will be understandably traumatized, may feel responsible for their loved one’s death, and in some cases feel that suicide is their own inevitable fate. One recognized precipitating event of a suicide is that of another. Dissemination of the details of a suicide has been identified as an instigating factor in the subsequent complete and incomplete suicides of others. As noted by Maris, there is no reason to doubt this association because humans are basically imitative of each other [4]. This is termed suicide contagion.

This paper will discuss the impact of the suicide of another upon a vulnerable population when that information is learned through traditional media, the Internet, and personal contact. Media guidelines developed to ameliorate this copycat effect in the reporting of suicides will be described. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic as a precipitating and/or contributing factor will be reviewed. Suicide risk screening in attempt to identify those at risk will be presented.

Definitions of the Terms Discussed

Suicide is a death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with an intent to die as a result of the behavior. Suicide attempt is a non-fatal self-directed and potentially injurious behavior with an intent to die as a result of the behavior. The suicide attempt may or may not result in injury. Suicide contagion is an increase in suicide and suicidal behaviors as a result of the exposure to suicide or suicidal behaviors within one’s family, peer group, or through media reports. Direct and indirect exposure to suicidal behavior has been shown to precede an increase in suicidal behavior in persons at risk for suicide, especially in adolescents and young adults. The concept is based on the theory that suicide is a socially contagious phenomenon [5]. Suicide cluster is defined as three or more united suicide events in a series in a common space, such as a school or community, and/or in a limited and contiguous time frame, usually 7 to 10 days. It has been estimated that 5% of adolescent suicides occur in clusters [6], which has been further categorized as a point cluster [7]. Some authorities have distinguished the term “cluster” from “contagion.” Cluster is defined as the proximity of time or location or both. Contagion implies a type of “contact” mechanism through which the “disease” is spread. Contagion has been analyzed as a mechanism for the suicide cluster including contagion-as-transmission (transmission of the suicide or its related components within a specific community or institution, inferring spread based on proximity); contagion-as-imitation (a stimulus response process, based on interpersonal, group and mass media communications); contagion-as-context (perceived change of group norms which reduce the threshold at which suicidal behavior is seen as an acceptable response to significant stresses); and contagion-as-affiliation (based on an affiliation with others with similar characteristics or like-minded attitudes) [8]. An increase in suicide rates after the widespread reporting of the facts on a suicide or group of suicides has been termed a mass cluster. The indiscriminate and sensationalized reporting of suicides, most often involving celebrities, has been identified as the precipitating event for a mass cluster. A point cluster is an increase in suicides in a more concentrated time period and geographical area such as in schools. Point clusters may go undetected and unreported due to the lack of recognition of the increase in suicides or suicide attempts in a limited geographical area [7].

Incidence and Scope of the Problem

International statistics reveal an alarming suicide rate, making suicide a significant health concern with implication for the practice of all healthcare providers. In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated a worldwide suicide rate of 10.6% per 100,000 persons with the greatest incidence (estimated at 89%) occurring in low and middle class countries. It was the 18th leading cause of death in 2016 [9]. Suicide deaths exceeded those of natural disasters, violence by others, war, and conflicts. Although suicide rates worldwide were found to be decreasing between 2000 and 2016, the exception was in the USA where the rates increased by 1.5% annually after 2000 [10, 11]. Globally, suicide accounted for 71% of female and 50% of male violent deaths. In the USA in 2018 among persons ages 12 to 34, suicide was the second leading cause of death [12]. Between 1999 and 2018, the national suicide rate increased by 35%. There was an average increase of approximately 1% annually between 1999 and 2006 and 2% annually between 2006 and 2018. In 2018, the suicide rate for males was 3.7 times that of females. Suicide rates in females were highest in the age groups of 45–64 and for males in the ages 75 and over. Suicide rates were higher in rural counties when compared to those in urban counties for both genders [13]. Although in 2020 the suicide rates during the COVID-19 pandemic have dropped, there has been caution in those reporting this result as an accurate reflection of the problem.

With such significant suicide rates, which do not include failed or incomplete suicide attempts, it is evident that the identification of vulnerable persons for suicide should not be limited to the healthcare practices of those dealing with mental illness. An individual’s suicide risk is not stagnant and can increase and decrease over their lifetime in response to the stressors encountered at a given time. Screening of a patient population for signs of depression and suicidal ideations has become routine in many healthcare settings outside. In the trauma care setting, a concern for identification of the patient at risk for suicide should be part of the scope of care provided, not only for those being treated for self-inflicted injuries but also for those with traumatic injuries which can be a precipitating factor in a post-recovery risk for suicide.

Predisposing and Precipitating Factors

In order to understand the concept of “suicide contagion,” the factors that make one “vulnerable” to the “contagion,” that is predisposed to suicidal ideations and suicidal behavior, need to be understood, which is comparable to the identification of the immunocompromised patient in assessing risk to infection.

Predisposing factors for suicide include psychiatric disorders, previous suicide attempts, sexual abuse, and family history of suicidal behavior, including the loss of a parent to suicide in early childhood. These risk factors come into play with different intensities at the different times in a person’s life and suicide can be the result of a culmination of factors. Psychiatric disorders, including bipolar disorder and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, as well as depression have a particularly strong impact on suicide rates over a lifetime. Substance abuse, epilepsy, and traumatic injury also increase the risk of suicide [14].

Precipitating factors interact with the individual’s predisposing factors. Among precipitating factors are stressful life events, such as relationship difficulties, death of a partner, the suicide of a person to whom the individual was close, e.g., a mother or child, diagnosis of a chronic medical condition, being the victim of assault, arrest, and imprisonment. Other related factors are younger age, unmarried, and fewer years of formal education [15].

Fazel has described a stress-diathesis psychological model to explain suicide as an interaction of stressors in vulnerable persons that express itself in suicidal ideations which are magnified by impulsivity and aggression [14]. Precipitating factors can cause psychological changes including feeling isolated, hopeless, and burdensome. The interrelationship between the predisposing and precipitating factors on the individual varies with the person’s resilience. For those predisposed to suicidal behavior, the suicide of another can be a significant precipitating event leading to a suicide attempt or completed act. Kral has described suicide as the result of the interaction of two conditions: perturbation and lethality. Perturbation is defined as stress, anguish, pain, depression, pressure, shame, agony, and mental disorder. Lethality is the idea of suicide or the option of death as a way to stop the perturbation [5].

There has been significant research into the question of the neurochemical causes of mental disorders and suicidal ideations. Neuroimaging studies of those with mental disorders such as bipolar and mood disorders have found anatomical differences observed in the brains of those with suicidal ideations. This has provided insight into an anatomical/physiological base to explain why certain persons are vulnerable to the development of suicidal ideations and the impulse to act on them. The imaging modalities utilized included structural MRI, functional neuroimaging, including single photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT), positron emission tomography (PET), and functional MRI. The goal has been to identify the association between the physiological and structural findings that will allow identification of persons at risk for suicidal behavior through the identification of common elements that are present in the at-risk groups and an understanding of the neural changes associated with this condition that are both current and a lifetime indicator. The ultimate goal is the identification, prevention, and intervention of suicide in the at-risk groups [16]. Johnston found in adolescents and young adults with bipolar disorder who attempted suicide less gray matter volume and decreased functional connectivity in a ventral fronto-limbic neural system which controls emotional regulations. It has been hypothesized that a reduction in the amygdala prefrontal functional connectively may be associated with the severity of the suicide ideation and lethality of the attempt [17].

Serotonin has been implicated as a factor in those who have attempted or committed suicide. In post-mortem studies, a decrease in serotonin transporter binding was found in the prefrontal cortex. Those who attempt suicide using a more lethal means showed decreased activity in the pre-frontal cortex. Mann noted that the neurological factors underlying the propensity of an individual for suicidal behaviors are diverse, complex, and interactive but the primary biological marker for suicide is probably too little serotonin in the prefrontal cortex. He described a stress-diathesis explanatory model of suicidal behavior with integrated clinical and neurobiological components. A trait deficiency in serotonin input to the prefrontal cortex was found in association with suicide and non-fatal suicidal behavior. It has been linked to decision-making and suicide intent in imaging studies and in vivo studies. It has been opined that the same neural circuitry and serotonin deficiency contribute to impulsive aggressive traits that are part of the diathesis for suicidal behavior and associated with early-onset mood disorders. Thus, these persons are at a greater risk for suicidal behavior [18].

The Suicide of Another as a Precipitating Factor

The acceptance of suicide as an acceptable option to end physical and/or emotional pain is one that is internalized by those vulnerable to suicidal ideation. When a person who is respected and emulated dies by their own hand, the idea of suicide can become normalized and seen by vulnerable individuals as an acceptable choice as a method to permanently cease consciousness or as an escape plan [5].

Media Reporting

Traditional Media: Print, Television, and Digital Media

Historically, it was the fictionalized accounts of suicides that led to evidence of suicide contagion. In 1774, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the celebrated German author, published a novel entitled “The Sorrows of Young Werther.” It described a troubled young man who fell in love and became obsessed with a woman whom he could not have. He became despondent and his mental state deteriorated culminating in his suicide by a self-inflicted gunshot wound using the pistol of this woman’s fiancé. The book was considered one of the first bestsellers and soon after its publication it gained a cult following. There was an increase in suicide rates seen in several European countries. This resulted in the novel’s ban in Leipzig, Italy, and Copenhagen. Although Werther is most often cited as the first example recognized as suicide by imitation, it was preceded by the Japanese Kabuki play, Love Suicides at Sonezaki, published in 1703 which was linked to a wave of suicides resulting in its ban in 1720 [19]. This was termed the “Kabuki effect.”

In 1974, the sociologist David P. Phillips coined the term “the Werther effect” to describe the mimicry of suicide after a highly publicized suicide. Phillips found that suicide appeared to behave as a contagion mediated idea by such publicized events. He found an increase in suicides that occurred immediately after the publication of stories concerning suicides which were publicized in British and US newspapers during the period of 1947 to 1968. The greater the publicity of the suicide story, the greater the rise in suicide rates thereafter, which were mainly in the limited geographical area in which the stories were publicized. This supported the conclusion that the increase in suicide rate was due to the influence of suggestion upon subsequent suicides not previously shown on a national level [20]. Two well-known and widely publicized suicides in their respective countries illustrate this concept. The suicide of Marilyn Monroe was followed by a 12% increase in suicides in the USA and 10% in England and Wales. The suicide of the English osteopath, Stephen Ward,1 who was well known because of his involvement in the Profumo affair, was followed by an increase in the suicide rate of 17% in Britain and 10% in the USA [20]. Thomas Niederkrotenthaler and colleagues have estimated that over 150 studies have confirmed this association, finding that the reporting of the death of celebrity by suicide had meaningful impact on total suicide rates in the general population, with the greatest increase by the same method used by the celebrity [21].

The impact of culture is evident in the copycat effect of the popular Korean actress, Jin-Sil Choi, in 2008. A total of 429 additional suicides were found occurring during the massive publicity of her death. When compared to the additional 197 deaths after Marilyn Monroe’s death in 1962, a greater impact is evident, especially when considering that Korea had a population less than one-fourth that of the USA. The media coverage of her death not only violated media guidelines for reporting suicides but also improperly gave details of the method she employed [22]. After the reported hanging suicide of the actor/comedian Robin Williams in 2014, the suicide cases in the USA increased by 1841 or a 9.85% increase from August to December of 2014. This increase was seen across all ages and gender groups but males and persons of the ages of 30–44 showed an excess of these suicides. There was also an increase in the method of suicide by suffocation [23]. In Canada, there was an increase in the suicide rates estimated by time series modeling of 16% of expected suicides from August to December of 2014. The greatest number of these excess suicides occurred in those over 30 and by suffocation. This occurred despite Canadian efforts at improvement in the method of mainstream media coverage of suicides [24].

Gould and colleagues found that the more prominent the reporting of a suicide story, with recounting of the explicit and detailed facts regarding the method, the greater the increase in copycat suicides triggered in the younger population [25]. This was found to be greatest in the first 3 days, reducing thereafter, but when the coverage continues to be prominent and repeated the impact continues beyond this time period [25]. The report of the specific method of suicide used has been found to result in the subsequent suicide actors using the same lethal method as that reported. The young are the most vulnerable to the impact of such stories especially those suffering from depression or who in some way identified with the deceased [26].

Violent mass shootings are often associated with the suicide of the perpetrator. A substantial portion of the perpetrators of mass shootings take their own lives [27]. The greater the amount of media attention given to such mass shootings resulting in an intense level of attention to the event creates a social landscape in which the perpetrator is given a national audience for their violent acts, and celebrity status posthumously, resulting in copycat events [28]. As a result, the media’s reporting of such events has come under scrutiny for being a precipitating factor because of the dramatic presentation and the intense coverage.

Fictionalized Representations of Suicide

Fictionalized stories concerning suicide also can cause a spike in suicides as noted in the “Werther” and “Kabuki” examples. A contemporaneous increase in suicides and suicidal ideations was seen in response to the Netflix series “Thirteen Reasons Why.” In March 2017, Netflix released this serial streamed fictionalized account about a teenage girl who committed suicide leaving behind thirteen tapes recounting why she chose suicide and those she held responsible. The series contained graphic suicide content. Niederkotenthaler and colleagues found that despite content warnings and the identification of suicide prevention services during the airings, there was an immediate increase in suicides that exceeded the generally increasing trend in the target audience of the program of 10- to 19-year-old individuals in the 3-month period after the show’s release. The increase was greater in females and the younger the viewer the greater the impact found [29].

Social Media and the Internet

The pervasive presence of the Internet and the constant use of digital devices, especially among the young, allow widespread and rapid dissemination of stories about suicides, near suicides, and mass acts of violence. There is little to no regulation of the content that is spread. The Internet also contains pro-suicide websites that endorse suicide by providing how to methods and/or by promoting discussion encouraging suicides [30–32]. Those who search for suicide-related content may be influenced by the information found, depending on a range of factors, including their own vulnerability and mood state at that time. A positive correlation has been found between the rate of Internet use and suicide rates. Dunlop found that the Internet, particularly social networking sites, is an important source of suicide stories, especially in the young. Discussion forums were particularly associated with suicidal ideations in the vulnerable population [33, 34].

The Internet provides a forum for cyberbullying, which is defined as the willful and repeated harm inflicted through the use of computers and other electronic media. All forms of bullying have been associated with an increase in suicide ideation and attempts. The Internet allows for a greater, faster, and anonymous dissemination of the aggression. Cyberbullying can be the factor that pushes a suicide ideator over the edge by providing the impetus to transition from the ideation to attempt [35].

Media Guidelines for Reporting of Suicides

In contrast to the harmful Werther effect, a potential positive effect, known as the Papageno effect, has been described. The term Papageno comes from Mozart’s opera “The Magic Flute” where the lovelorn character contemplates suicide until other characters in the opera show him another way to resolve his problems. Niederkrotenthaler and others have shown that media reports that provide information about methods of coping with adverse circumstances were associated with a decrease in suicides thereafter where that media reached a large audience [36]. Recognizing the aforesaid, guidelines have been developed by multiple organizations regarding the manner and content of reporting on suicides and mass shootings. The aim is not only to reduce the harmful impact of the media story by guiding the content but also to provide important protective information regarding suicide prevention and mental health resources, while giving direct links to mental health and suicide hotlines. Among such guidelines are those of the World Health Organization, CDC, Canadian Psychiatric Association, and Suicide.Org. [37].

The guidelines generally recommend avoiding:

Descriptions of the method and location of the suicide.

Sharing the content of a suicide note.

Describing intimate details of the person who died.

Presenting the act of suicide as an acceptable or common response to a hardship.

Oversimplifying or speculating the motivation for the suicide.

Sensationalizing the details in the story.

Glamorizing or romanticizing the suicide or person who has committed suicide.

Using terms such as epidemic or skyrocketing when discussing suicide.

Engaging repetitive, ongoing, and excessive reporting of the suicide.

The guidelines generally recommend:

Report the suicide in general terms.

Report that a note was found but omit the details.

Report only general details about the person.

Provide coping skills, support, and treatment available for those who have contemplated suicide.

Describe warning signs, risk factors, and mental illness associated with suicide.

Report the suicide and death using facts and language that are sensitive to those surviving the decedent who are grieving.

When describing the incidence of suicide use the best available data and use words such as increase or rise.

The same guiding principles have been recommended regarding media reporting of mass shootings including those associated with suicide [38–42].

The Internet has been employed as a media forum to provide protective information and counter the impact of those sites that disseminate information about suicide methods and promote it as an acceptable response to stress and anxiety. The National Suicide Prevention website provides contact information and links to suicide prevention organization. The Google search engine displays a link and message about the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at the top of the search page when the search working suggests suicidal ideations. Facebook coordinated with the UK and the Ireland-based Samaritan organization to create a suicide alert reporting system so that its users could report individuals who they believe are expressing suicidal thoughts [43].

The Suicide of a Near Contact

Suicide contagion can be the result of direct knowledge of the suicide of a close friend or family member. It has been found that the survivors of one who has taken their own life have an increased risk of suicide. The reason is multifactorial and illustrates the significance of the predisposition of the survivor for suicidal ideations. The survivor may have mental health conditions and treatment needs similar to the decedent, including a mood or anxiety disorder being treated with psychiatric medication. Maris found a 11–12% rate of suicides in a first-degree relative of those who had committed suicide as compared to no increase in the survivors of the natural death of a loved one [44]. The survivor may have his own de novo suicide ideations and self-destructive behavior. Suicide rates have been found to increase in survivors just before or after the death of the loved one and thereafter on important dates such as the anniversary of the death, birthdays, and wedding anniversaries.

Pittman et al. found that the attitude about suicide in certain vulnerable adults bereaved by the suicide of of a close friend or relative was influenced in such a way that it could increase their own risk of suicidal action. Those who perceived themselves as susceptible to suicide described a sense of inevitability which they either fought or to which they submitted. Some conveyed a fear of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Clinical factors such as depression, substance abuse, and personality traits were identified as creating a higher risk of suicide due to a fundamental change in their attitude to suicide since the loss of their loved one [45].

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Because of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, another type of suicide contagion has become a concern requiring a reverse analysis of the concept of suicide and contagion. In this analysis, the COVID-19 pandemic is the precipitating event resulting in an increase in subsequent suicidal ideations or actions. The COVID-19 pandemic has been termed a “dual pandemic” [46]. The widespread dissemination in the media concerning the virus, its virulence, the lack of effective treatment, and the disturbing death rates are but a few of the factors that created fear and anxiety in the general public. Inconsistent and conflicting messaging and the politicization of the pandemic were further aggravating factors. Individuals already suffering from mood disorders, psychiatric conditions, and stress, including those of a physical, mental, and/or economic nature, were and still are at risk for the development of suicidal ideations and action. It is not only the fear of the virus that has precipitated this increased risk but also the governmental/public health actions taken to minimize the spread of the virus, which have caused their own set of adverse outcomes. These include isolation, the economic stress, decreased access to community and religious support, barriers to mental health treatment, and exacerbation of medical conditions. Groups especially impacted include frontline workers, elderly, homeless, victims of abuse and violence, stigmatized groups, and those in financial crisis. The result is an increase in depression, anxiety, fatigue, post-traumatic stress disorder, and adjustment disorder [47, 48]. The concern has and continues to be that these will precipitate suicidal ideations and follow through behavior. Although a significant increase in the suicide rates has not been definitively established as a result of the pandemic at this time, it is recognized that there is a significant need for intervention to mitigate the impact of the pandemic and the containment actions taken. The impact of a public health crisis as a precipitating factor is not new to the COVID-19 pandemic. It was seen in prior epidemics and pandemics, including that involving severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), H1N1, Ebola and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and Ebola and the 1918 Spanish flu [49].

It is not only the socioeconomic impact of the virus that has been recognized as a potential precipitating factor for the increase in suicide ideations and actions but the pathophysiology of the virus itself has a direct physiological impact which can influence a person’s potential for suicide. It has been recognized that dysregulation inflammation is associated with depression and suicidal behaviors. Studies have found an increase in interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of suicide attempters [50]. Isung et al. found that suicide attempters with more impulsive and sensation-seeking personality traits had significantly higher plasma levels of IL-6 than non-violent attempters, leading to the hypothesis that extraversion and violent methods of suicide were independently associated with increased IL-6 levels. This comports with prior findings that an inflammatory process is associated with impulsivity and aggression [51]. The physiological response to the COVID-19 infection can include the development of a cytokine storm which has been identified as playing a role in the precipitation of a suicide. IL-6 plays a significant role in the release of cytokines and what is termed the cytokine release syndrome [52]. Alterations in the psychoneuroimmunity of the brain and other organs have been seen in COVID-19 evidencing the relationship of immunity, the brain, and mental health. There is a concern that there may be an increase in suicide risk as a result of the inflammation and immunity dysregulation caused by the neuropathogenesis of the virus.

Healthcare professionals have been and still are particularly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Even before the pandemic, rates of physician burnout, depression, and suicide were concerning. As with the general public, the physician and frontline healthcare provider who suffer from predisposing conditions such as mental health/mood disorders, substance abuse, and a family history of suicide have an increased vulnerability to the impact of the stress of dealing with impact of the pandemic. Frontline healthcare providers are under a significant degree of stress as they have and continue to deal with the overwhelming demands and responsibility of caring for patients with COVID-19. They have and still do care for patients presenting with a formerly not seen overwhelming and multisystem organ failure which was not initially understood and for which there is no one definitive treatment. The death rates experienced were beyond those ever experienced. For those patients who did not survive, the healthcare provider many times was the last person with whom the patient interacted before their death. They were the intermediary through whom the patient and family communicated during this extremely stressful and emotional time, including saying final farewells. The lack of personal protective and essential medical equipment experienced during the pandemic caused stress due to a lack of control and support. The long hours of work without sufficient time off did not allow for adequate periods of recovery. The healthcare providers placed themselves at risk for infection with its high mortality rate and many experienced not only the deaths of their patients but also those of colleagues. Some had to witness allocation of limited resources and equipment as well as hasty end-of-life decisions. They feared bringing the infection home to their family resulting in an inability to care for their own family and a self-imposed separation and isolation in an effort to protect loved ones. This created a toll that has and will continue to be seen after the pandemic has been finally contained. Already high levels of burnout and psychological symptoms in healthcare workers have been confirmed resulting in a range of responses from increased anxiety to depression and post-traumatic stress disorders [53–55]. The suicide of Dr. Lorna Breen is a well-reported example of the potential impact of the virus on physicians. She was a supervising physician during the height of the pandemic in New York and became ill with the virus. Despite recovering from the virus and returning to work, she developed a significant depression from which she did not recover, ultimately taking her own life [56].

For all who are impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, including those not previously predisposed to suicidal thoughts, care must be taken to recognize the physiological and psychological impact of the virus both directly and indirectly. This requires support provided by the family, community organizations, and government, both at the local and national levels, such as that legislated in the American Rescue Plan-H.R. 1319.

The Implications for Clinical Practice

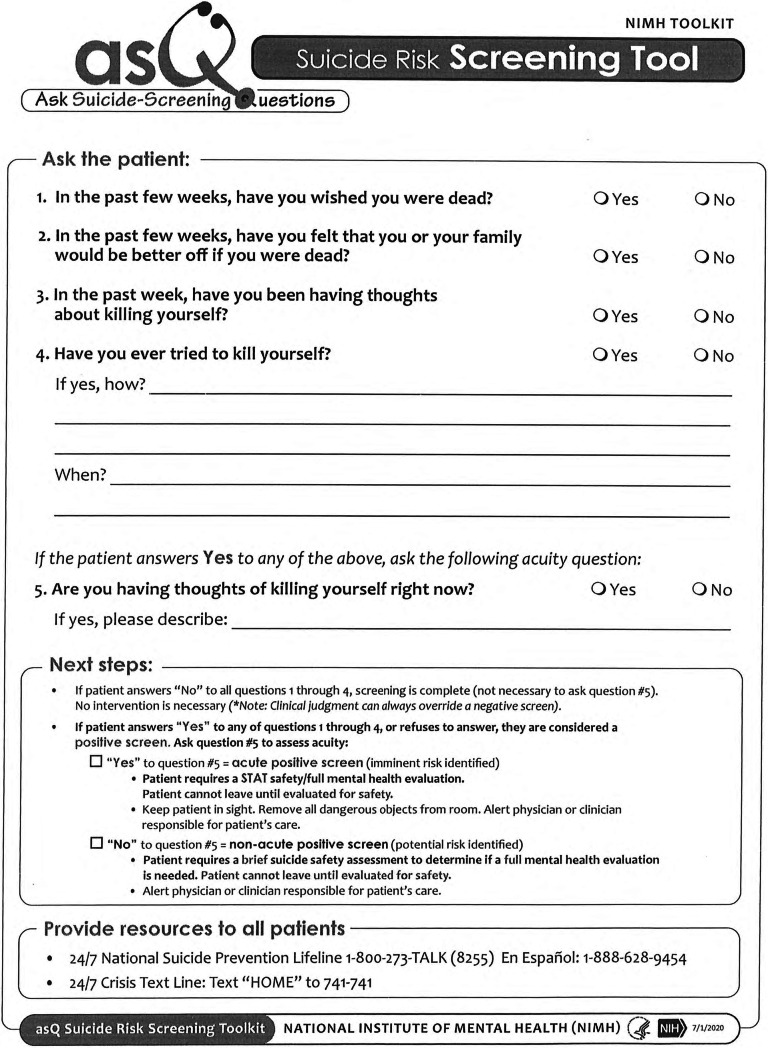

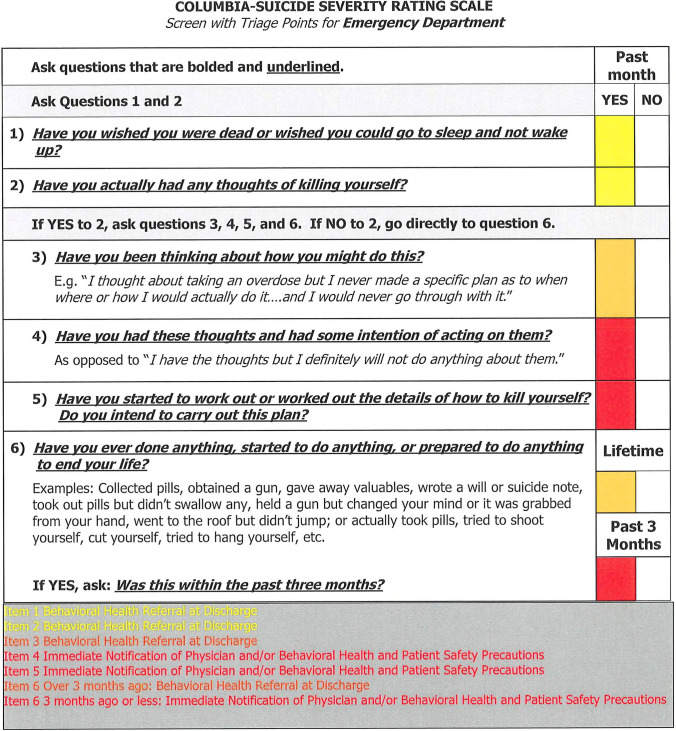

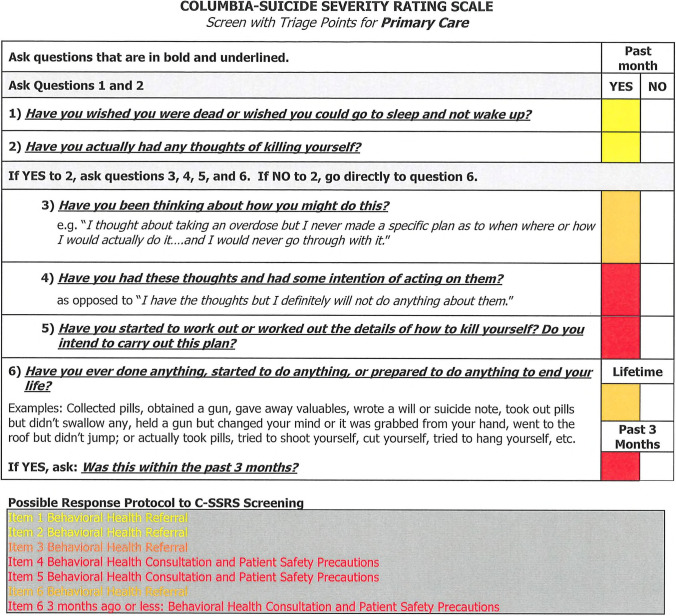

The study of suicide contagion reveals one consistent concept, the need to recognize those vulnerable individuals who due to predisposing factors are susceptible to the idea of suicide as an acceptable ultimate option to deal with their pain, both physical and psychological. The Joint Commission issues annual reports on National Patient Safety Goals which include suicide prevention and requirements suicide risk assessment. In July 2020, the requirements were extended to all Joint Commission–accredited hospitals including critical access hospitals. The goal is to improve the quality and safety of the care to those being treated with behavioral conditions and identify those at risk for suicide [57]. The requirements mandate the screening of all patients for suicidal ideations using a validated screening tool. Among the validated screening tools cited are the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) of the National Institute of Mental Health (Table 1) [58], the Columbia Suicide Rating Scale (CSRS) which has questionnaires designed for use in different clinical settings including the Emergency Department (Table 2) [59], and Primary Care office (Table 3) (58). The tools include questions about whether the patient has had thoughts in the past few weeks of their own death, wishing that they were dead, feeling that others would be better off if they were dead, thoughts of killing themselves, and past attempts at suicide. When there is a positive answer, the interviewer is prompted to put into place safety measures until the patient is evaluated by a clinician. Because these questions are part of the electronic medical record template, the risk is that for a patient who does not have an overt behavioral or mental health issue or one that is primary to the encounter, the questions will not be asked or merely glossed over. Another consequence is that patients who have mental disorders may screen positive causing the required response which can be burdensome to the emergency room/urgent care provider who must decide if the patient must be placed on one-to-one observation, evaluated by a psychiatrist, and if not admitted to the hospital referred for mental health intervention and care. This may lead to a reluctance to identify a patient at risk if their presentation in the emergency room does not overtly exhibit an immediate risk for suicide causing the interviewer to fail to recognize a patient at risk. Many primary care providers use such screening tools because these questions are embedded in the electronic medical record template and not necessarily part of an intentional suicide risk assessment. Ideally, it is the primary care provider who knows their patient and can identify those predisposed to the negative impact of a precipitating stressor, such as the death of a loved one and in particular when the death is by suicide. For those assessing a patient’s suicide risk, a careful history can allow identification of predisposing and precipitating factors which will allow for a sensitive and accurate determination.

Table 1.

Ask Suicide Screening-Questions. National Institute of Mental Health. With permission of National Institute of Mental Health. NIMH.nih.gov/research/research-conducted-at-nimh/asq-toolkitmaterials/index.html. 2020

Table 2.

Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. Emergency Department. With the permission of The Columbia Lighthouse Project

Table 3.

Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. Emergency Department, primary care. With the permission of The Columbia Lighthouse Project

Conclusion

Suicide is a serious public health concern resulting in significant mortality and morbidity each year. A factor that has been identified in the precipitation of a suicide attempt or completed act is the suicide of another, whether that person was a famous personality or a close loved one. The greatest risk of suicide by contagion exists in those who are vulnerable due to predisposing factors resulting from genetic, biological, and sociological factors. The goal is to identify and protect such persons by providing the required support, which can include evaluation and treatment by a mental healthcare and medical provider, economic support, and when necessary safety precautions, such as hospitalization, to prevent the patient from acting on a suicidal intent during a period of crisis. Knowledge and sensitivity to the patient’s risk factors as they exist at a given time in their life assist the healthcare practitioner to provide the required intervention to the patient and when appropriate to the patient’s family and significant others.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interests with the content of this article.

Footnotes

Stephen Ward took his life after being found guilty of two counts of living off immoral earnings. He had been deemed a societal osteopath who had introduced the British Secretary of War, John Profumo, to a 19-year-old showgirl. When the affair came to light in 1961, it led to the disgrace of Secretary Profumo and his resignation. During the trial, Ward was subject to the abandonment of his former society friends and subject to the hostility of the judge and prosecuting attorney.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Intentional Violence

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ahmad FB, Cisenski JA, Minion A, Anderson RN. Provisional mortality data-United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(14):519–522. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7014e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curtin S, State suicide rates among adolescents and young adults aged 1–24: United States, 2000–2019. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2020: 69;2; National Centers for Health Statistics. [PubMed]

- 3.Shepard DS, Gurewich D, Lwin AK, Reed GA, Jr, Silverman MM. Suicide and suicidal attempts in the United States: costs and policy implications. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2016;46:3. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kral, MJ The idea of suicide, contagion, imitation, and cultural diffusion, New York Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: 2019, Chapter Chapter 3, page 47.

- 5.Kral MJ. The idea of suicide, contagion, imitation, and cultural diffusion, New York Routledge Taylor & Francis Group; 2019, Introduction, p. 1-18. Important for a comprehensive review of the sociological theories of suicide

- 6.Maris RA, Suicidology-a omprehension biopsychological perspective. New York; The Guilford Press; 2019. , Chapter 7, Social relations, work, and the economy social versus individual factors, p. 129.

- 7.Poland S, Lieberman R, Niznik M. Suicide contagion and clusters-part 1: what school psychologists should know. National Association of School Psychologists. 2019;5:21–23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Q, Li H, Silenzio V, Caine ED. Suicide contagion: a systematic review of definitions and research utility. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e108724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Work Health Organization, Age-standardized suicide rates per 100,000 population, both sexes, 2016 Geneva: World Health Organization. 2018. who.int/gho/mentalhealth/suicide_rates/en/. Accessed 4/2/2021.

- 10.Stone DM, Simon TR, Fowler KA, et al. Vital signs: trends in state suicide rates-United States, 1999–2016 and circumstances contributing to suicide-27 states, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:617–624. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67:617–24; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multiple cause of death, 1999–2017. CDC Wonder Online Data Base wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html. Accessed 28 Mar 2021.

- 12.Center for Disease and Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. (WISQARS)[online]. (February 2020. Retrieved from (https://www.cdc.gov/injurywisquars). Accessed 25 Mar 2021.

- 13.Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, Warner M. Suicide rates in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief 2020; 362, Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

- 14.Fazel A, Runeson B. N Eng J Med. 2020;382(3):266–274. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1902944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Cross national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempt. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox Lippard ET, Johnston JA, Blumberg HP. Neurobiological risk factors for suicide: insights from brain imaging. Am J Prev Med. 2014; Se[‘ 47: (3 Suppl 2):S152–162. doi:10.1016/j.ampres.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Johnston J, Wang, F. Liu J, et al. Multimodal neuroimaging of fronto-limbic structure and function associated with suicide attempts in adolescents and young adults with bipolar disorder. Amer J Psychiatry: 2017 July 01; 174:7: 667–675. doi:10.1 176/appi.ajp.2016.15050652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Mann J. The serotonergic system in mood disorders and suicidal behavior. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368(1615):20120537. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krysinska K. Suicide in Kabuki theater. In: Niederkrotenthaler T, Stack S, editors. Media and Suicide. International perspectives on research, theory and policy. New York : New York: Routledge; 2017. p. 119–29.

- 20.Phillips D. The influence of suggestion on suicide: substantive and theoretical implications of the ‘Werther effect’. American Sociological Review. 1974; 39 3: 340–354. Retrieved April 2, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2094294c. Accessed 4/2/2021. [PubMed]

- 21.Niederkrotenthaler T, Stack S. Introduction. In: Niederkrotenthaler T, Stack S, editors. Media and Suicide. International perspectives on research, theory and policy. New York: New York: Routledge; 2017. P. 1–13. Important recitation of the underlying theory and research regarding suicide and its relation to media coverage.

- 22.Lee J, Lee WY, Hwang JS, Stack SJ. To what extent does the reporting behavior of the media regarding a celebrity suicide influence subsequent suicides in South Korea? Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(4):457–472. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fink DS, Santaella-Tenorio J, Keyes, KM. Increase in suicides the months after the death of Robin Williams in the US. PLos ONE 13(2):30191405. 10.1371/journal.pone.0191405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Whitley R, Fink DS, Tenoria S, Keyes KM. Suicide mortality in Canada after the death of Robin Williams, in the context of high-fidelity to suicide reporting guidelines in the Canadian media. Can J Psychiatry. 2019;64(11):805–812. doi: 10.1177/0706743719854073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bollen KA, Phillips DP. Imitative suicides: a national study of the effect of television news stories. Am Sociol Rev. 1982;47(6):802–809. doi: 10.2307/2095217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng ATA, Hawton K, Chen THH, Yen AMF, Chang JC, Chong MY, et al. The influence of media reporting of a celebrity suicide on suicidal behavior in patients with a history of depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;103:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Preti A. School shooting as a culturally enforced way of expressing suicidal hostile intentions. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(4):544–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gould MS , Olivares M. Mass shootings and murder-suicide: review of the empirical evidence for contagion. In. Niederkrotenthaler T, and Stack S, editors. Media and suicide, international perspectives on research, theory and policy, New York: Routledge; 2017. p. 49–65.

- 29.Niederkrotenthaler T, Stack S, Till B, et al. Association of increased youth suicides in the United States with the release of 13 Reasons Why. JAMA Psychiat. 2019;76(9):933–940. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Till B, Niederkrotenthaller T, Herberth A, Vitouch P, Sonneck G. Suicide in films: the impact of suicide portrayals on nonsuicidal viewer’s well-being and the effectiveness of censorship. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2010;40(4):3109–27. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.4.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aitken A, Luxton D, Fairall J. Suicide and the Internet. Bereavement Care. 2012;28(2):40–41. doi: 10.1080/02682620902996129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luxton D, June J, Fairall, J. (2012) Luxton DD.. Social media and suicide: public health perspective. Am J Public Health. 2012;102 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S195-S200. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Thompson S. Social media and suicide: a public health perspective. Am J Public Health. 1999;102(2):196–200. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunlop SM, More E, Romer D. Where do youth learn about suicides on the Internet, and what influence does this have on suicidal ideation? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(10):1073–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stack S, Internet bullying distinguishes suicide attemptors from ideators. In: Niederkrotenthaler T. Stack S, editors., Media and suicide, international perspectives on research, theory and policy, Routledge Taylor. New York: Routledge; 2017. p. 67–74.

- 36.Niederkotenthaler T, Voracedk M, Till B, Strauss, M., Etzersdorfer E, Eisenwort B,Sonneck G. Role of media reports in contemplated and prevented suicide: Werther v Papageno effects. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2010: 197: 234–43). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.O’Carroll, W, Potter LB. Suicide contagion and the reporting of suicide: recommendations from a national workshop. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994; 43: No. RR-6: 9–18. [PubMed]

- 38.Gould MS, Olivares M. mass shootings and murder-suicide: review of the empirical evidence for contagion. In. Niederkrotenthaler T, Stack S, editors. Media and suicide, international perspectives on research, theory and policy, New York: Routledge; 2017. p. 41–65.

- 39.Kostinksy S, Bixler EO, Kettl PA. Threats of school violence in Pennsylvania after media coverage of the Columbine high school massacre: examining the role of imitation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;155(9):994–1001. doi: 10.1001/arcjpedi.155.9.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neuner T, Hubner-Liebermann B, Hajak G, Hausner H. Media running amok after school shooting in Winnenden. Germany Journal of Public Health. 2009;19(6):578–579. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preti A. School shootings as a culturally enforced way of expressing suicidal hostile intentions. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online. 2008;36(4):544–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richards T N, Gillespie LK, Givens EM. Reporting homicide-suicide in the news: the current utilization of suicide reporting guidelines and recommendations for the further. J Fam Violence. 2014;29:4: 453–463. 10.10007/s10896-014-9590-0.

- 43.Luxton DD, June JD, Fairall JM. Social media and suicide: a public health perspective. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl 2):195–200. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maris RW. Pathways to suicide: a journey of self-destructive behaviors. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press 1981.

- 45.Pitman A, Nesse H, Morant N, Azorina V, Stevenson F, et al. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:400. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1560-3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Banerjee D, Kosagisharaf JR, Sathayanarayana Rao TS. The dual pandemic’of suicide and COVID-20: a biopsychosocial narrative of risks and prevention. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:11357. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reger MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE. 2020 Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019-a perfect storm? JAMA Psychiatry. 2020; 77: 11: 1093–1094. Doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.John A, Pirkis J, Gunnell D, Appleby L, Morrissey J. Trends in suicide during the COVID-19 pandemics. BMJ. 2020;371:m4352. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m44532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.The links between public health crises and suicide. Suicide Prevention Resource Center, 2020 Education Development Center, Inc.

- 50.Lindqvist D, Janelidze S, Hagell P, Erhardt S, Samulesson M, Minthon L, et al. Interleukin-6 is elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of suicide attempters and related to symptom severity. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Isung J, Aeinehband S, Mobarrez F, et al. High interleukin-6 and impulsivity: determining the role of endophenotypes in attempted suicide. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4:e470. doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang C, Wu Z, Li JW, Zhao H, Wang GQ. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19: interleukin-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab may be the key to reduce mortality. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55(5):105954. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Azoulay E, Cariou A, Bruneel F, et al. Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and peritruamatic dissociation in critical care clinicians managing patients with COVID-19. A cross-sectional study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:1388–98. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2568OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Papp S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behav and Immunity. 2020, 88: 901-02. Important for timely discussion of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on precipitating factors in suicide. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Giusti EM, Pedroli E, D’Aniello GE, et al. The Psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on health professionals: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1684. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knoll C, Watkins A, Rothfeld M. “I couldn’t do anything”: the virus and an E.R. doctor’s suicide. The New York Time, July 11, 2020. www.nytimes.com/2020/07/11. Accessed 4/1/2021.

- 57.The Joint Commission, R3 Report Requirement, Rational, Reference. Issue 18, Nov. 27, 2018 updated Nov. 20, 2019. www.jointcommission.org/standards/r3-report/r3-report-issue-18-national-patient-safety-goal-for-suicide-prevention/. Accessed 3/15/2021.

- 58.NIMH.nih.gov/research/research-conducted-at-nimh/asq-toolkit-materials/index.shtml. Accessed 3/20/2021.

- 59.Retrieved from: cssrs.columbia.edu/documents/screener-triage-emergency-departments. Accessed 4/2/2021.

- 60.Gould M, Kleinman MH, Lake AM, Forman J, Basset MJ. Newspaper coverage of suicide and initiation of suicide clusters in teenagers in the USA, 1988–96, a retrospective, population-based, case-control study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(1):34–43. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Retrieved from:cssrs.columbia.edu/documents/c-ssrs-screener-triage-primary-care. Accessed 3/20/2021.