Abstract

Purpose:

Seizures occur in 10% to 40% of critically ill children. We describe a phenomenon seen on color density spectral array but not raw EEG associated with seizures and acquired brain injury in pediatric patients.

Methods:

We reviewed EEGs of 541 children admitted to an intensive care unit between October 2015 and August 2018. We identified 38 children (7%) with a periodic pattern on color density spectral array that oscillates every 2 to 5 minutes and was not apparent on the raw EEG tracing, termed macroperiodic oscillations (MOs). Internal validity measures and interrater agreement were assessed. We compared demographic and clinical data between those with and without MOs.

Results:

Interrater reliability yielded a strong agreement for MOs identification (kappa: 0.778 [0.542–1.000]; P < 0.0001). There was a 76% overlap in the start and stop times of MOs among reviewers. All patients with MOs had seizures as opposed to 22.5% of the general intensive care unit monitoring population (P < 0.0001). Macroperiodic oscillations occurred before or in the midst of recurrent seizures. Patients with MOs were younger (median of 8 vs. 208 days; P < 0.001), with indications for EEG monitoring more likely to be clinical seizures (42 vs. 16%; P < 0.001) or traumatic brain injury (16 vs. 5%, P < 0.01) and had fewer premorbid neurologic conditions (10.5 vs. 33%; P < 0.01).

Conclusions:

Macroperiodic oscillations are a slow periodic pattern occurring over a longer time scale than periodic discharges in pediatric intensive care unit patients. This pattern is associated with seizures in young patients with acquired brain injuries.

Keywords: Pediatrics, Quantitative EEG, Power spectrogram, Ictal–interictal continuum

Electrographic seizures occur in 10% to 40% of critically ill children, with the majority being subclinical.1,2 Electrographic status epilepticus and high seizure burden are associated with mortality and poor outcomes, including recurrent seizures, cognitive and behavioral sequelae, and decreased quality of life.2-6 This has led to increased continuous EEG (cEEG) utilization in intensive care units (ICUs)7 with quantitative EEG (QEEG) techniques enabling providers to more rapidly and efficiently identify seizures.8-12 The power spectrogram, or color density spectral array (CDSA), is a QEEG trend that displays EEG frequencies and power over time.13 This spectral readout uses fast Fourier transformation to decompose the raw EEG waves into its constituent frequencies at a given time. The CDSA is visualized with compressed time on the x-axis, frequency on the y-axis, and the power (microvolts squared) represented by colors. Typically, warmer colors (red/orange) indicate higher power and cooler colors (blue) indicate lower power. Color density spectral array can identify seizures in the pediatric ICU patients.10,12,14

In the process of identifying seizures on raw EEG and CDSA, we fortuitously identified a recurring pattern that occurred before or in the midst of recurrent seizures. The pattern was not visualized on a 10- to 20-second page of raw EEG. This CDSA pattern occurs over a prolonged time scale, is periodic, and regular with unvaried magnitude consistent with an oscillatory pattern; we refer to this pattern as macroperiodic oscillations (MOs). Here, we illustrate this phenomenon, describe the patient characteristics, and highlight opportunities for future research.

METHODS

This is a retrospective, observational study of children aged newborn to 21 years who underwent clinically indicated, cEEG monitoring between October 15, 2015 and August 30, 2018 in the pediatric, cardiac, and neonatal ICUs at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Washington University in St. Louis.

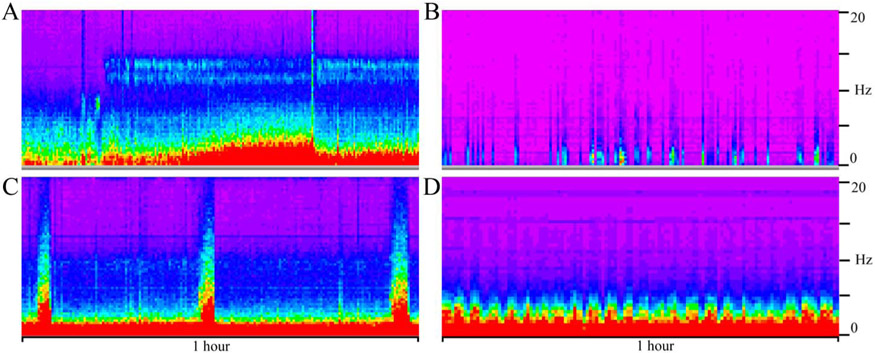

Macroperiodic oscillations were identified during clinical review of EEGs and defined as having a visually apparent oscillatory pattern best identified on a 12-hour CDSA of all channels or any individual channel, oscillating over minutes for at least five cycles, without recognizable change or correlate on 10- to 20-second raw EEG tracing. This pattern recurred with a very regular periodicity, making it distinguishable from normal background, seizures, or burst suppression (Fig. 1). Two board-certified epileptologists (R.M.G. and S.R.T.) or a senior clinical neurophysiologist (M.J.M.) reviewed 541 cEEGs obtained while on clinical assignment.

FIG. 1.

A color density spectral array of normal state cycling (A), burst suppression (B), seizures (C), and macroperiodic oscillations (D). Time is on the x-axis with these displays representing a 1-hour epoch of a 12-hour power spectrogram of all EEG channels. The y-axis is frequency from 0 to 20 Hz. Note the difference between the regular periodicity of macroperiodic oscillations (D) with the sporadic nature of burst suppression (B) and seizures (C).

Patients were identified during routine clinical review of raw cEEG and CDSA (Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan). Clinical EEGs have 21 channels (Fp1, Fp2, F7, F3, Fz, F4, F8, A1, T7, C3, Cz, C4, T8, A2, P7, P3, Pz, P4, P8, O1, O2) and a sampling rate of 200 Hz. The amplifier was non-DC coupled with 32 channels (model # JE-921) used for clinical acquisition. The low- and high-bandpass filters were set at 70 and 1 Hz, respectively. The standard, internal Nihon Kohden system reference is calculated from C3-C4, labeled 0 V. The included, proprietary CDSA is calculated using the system reference during EEG acquisition. The CDSA for all subjects was reviewed using the default settings with a 12-hour display with a sensitivity set at 3.5 mV and frequency range from 0 to 20 Hz.

Inclusion criteria required universal agreement between the three EEG reviewers (R.M.G., S.R.T., M.J.M.) for the presence of MOs in the CDSA of all channels or any single channel. To assess internal validity, 12 subjects were randomly selected from the study group. The on and off times of MOs, rounded to the nearest 30 minutes, was recorded based on a standardized review of the CDSA of all channels in a 12-hour file, blinded to EEG notations (see Supplemental Figure s1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JCNP/A152). The percent overlap was calculated by tallying the number of 30-minute bins for the longest epoch and comparing the other two raters against this. The total of overlapping bins divided by possible overlapping bins was recorded as percentage overlap. The mean of these percentages was calculated.

Where there was 100% concordance (10 subjects) in the percent overlap of the reviewers (R.M.G., M.J.M., S.R.T.), we sought to characterize MOs further. We measured the duration of MOs per reviewer (in minutes, without rounding) and created a series of panels using Persyst (Solano, CA) that included the power spectrogram, as well as fast Fourier transformation–based delta, theta, alpha, and beta power (microvolts squared per frequency band), and the peak envelope (microvolts for frequencies 2–20 Hz). We visualized EEGs on 120-minute time scale and recorded: time between peaks, peaks and troughs of the peak envelope, and power for each frequency band within subjects. We then calculated the ratio of peak to trough within subjects, and the means, medians, and ranges across subjects.

Finally, to establish reproducibility in identifying this phenomenon, two additional, board-eligible epileptologists with training in ICU-EEG (R.R. and J.L.G.), but limited familiarity with MOs were presented with 27 randomly selected screenshots of a CDSA display only, without access to EEG notations, clinical history, or the raw EEG. These CDSA displays contained MOs and seizures (11), seizures alone (5), or neither (11). Using the definition of MOs (a visually apparent oscillatory pattern occurring over minutes for at least five cycles), the raters determined the presence MOs and/or seizures.

To assess for clinical or demographic differences, subjects with MOs were compared with a subset of patients (n = 329) in the pediatric, cardiac, or neonatal ICUs who had cEEGs and did not have MOs on CDSA. All EEGs reviewed had a minimum of 12 hours of recording and 24 to 48 hours most commonly and were reviewed in their entirety for the presence of MOs. For patients with multiple EEGs during the investigation period, only the first EEG per admission was included in analysis.

Chart review was conducted to collect demographic and clinical data, including age, sex, reason for admission, premorbid conditions (including neurologic conditions), indication and duration of EEG, hospital duration, and location of monitoring. EEG data, including the presence or absence of seizures and the background from which MOs occur was recorded. Background was scored per previously published Likert scale15 with 1 = normal or sedated sleep, 2 = slow, disorganized (including excess discontinuity in neonates), 3 = burst suppression or severe discontinuity, and 4 = attenuated, featureless.

Statistical analysis was performed with Stata version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Continuous variables were compared using the Welch t-test to account for uneven sample size and variance. A χ2 test was used to determine differences in contingency tables (sex, indication, and unit), whereas a Fisher exact test was used if any of the groups in the contingency table had an expected value less than five. A 2-sided P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Internal validity and interrater reliability statistics included calculation of percent overlap of MOs duration, as well as sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and rater agreement (Cohen kappa) for the MOs and seizure metrics. To determine the relative contributions of MOs on electrographic seizures, a multivariable logistic regression was performed with forced inclusion of factors (because 100% of MOs patients had seizures), including patient age, neurologic premorbid conditions, and acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), because these have been previously associated with electrographic seizure incidence in critically ill children.16-18

RESULTS

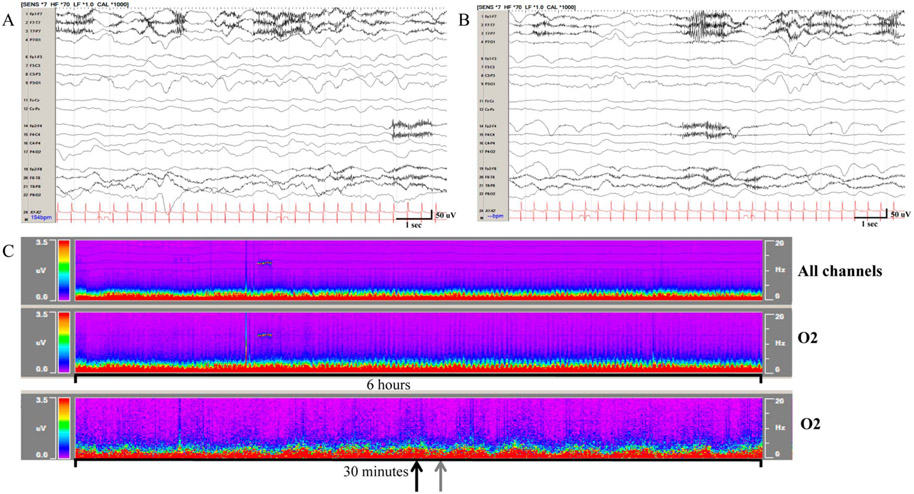

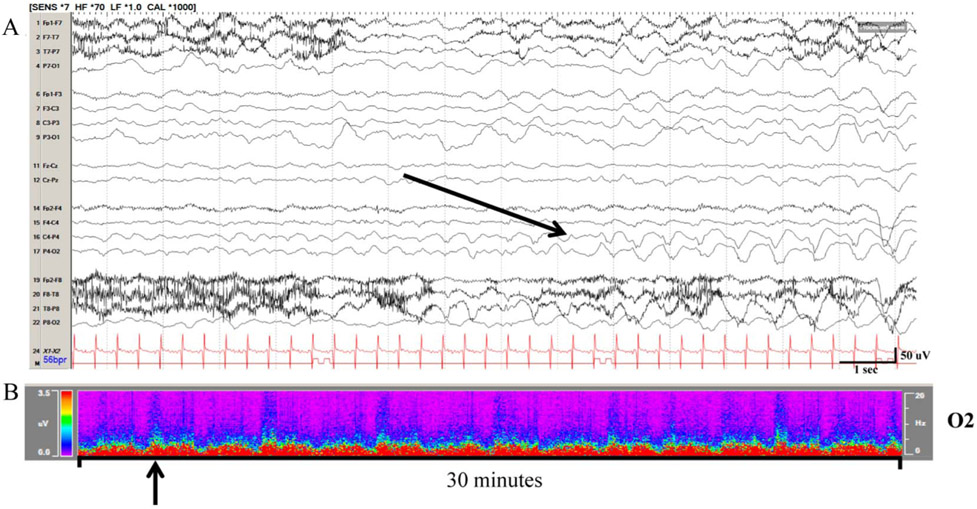

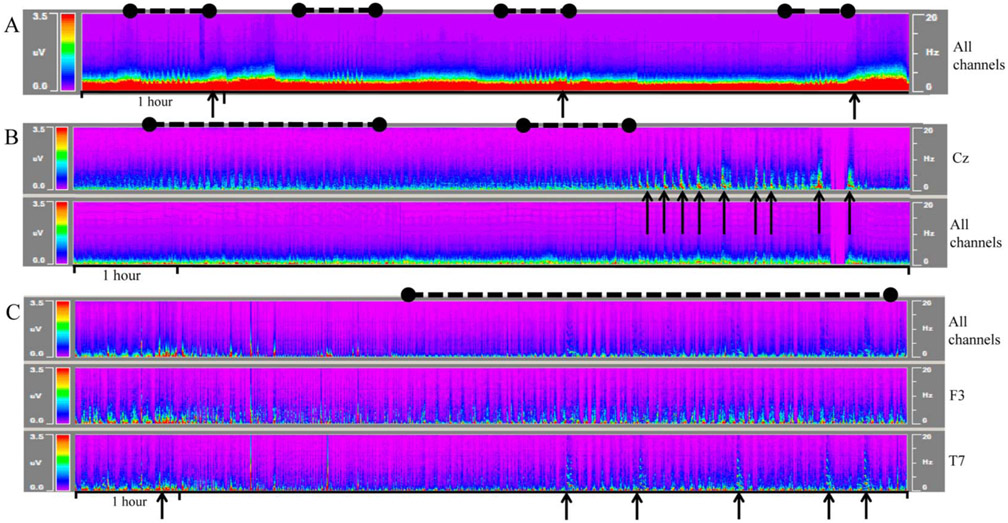

From October 2015 and August 2018, there were 975 EEGs obtained via searching our database across the neonatal, cardiac, and pediatric ICUs. The three primary reviewers (R.M.G., M.J.M., S.R.T.) read 595 of these studies (based on random clinical assignment, 394 for M.J.M., 133 for R.M.G., and 68 for S.R.T.). Of these 595, 16 were excluded for being older than 21 years and 38 were excluded for being additional studies. Of the remaining 541, 38 (7%) EEGs demonstrated MOs, defined as an oscillatory pattern on CDSA occurring at regular intervals. Macroperiodic oscillations were identified on the CDSA and are visually distinct from normal background, burst suppression, and seizures (Fig. 1). There was no discernible visual difference between the crest and trough of the pattern on raw EEG (Fig. 2). Macroperiodic oscillations occur independently of and are distinct from seizures (Fig. 3). Macroperiodic oscillations may be best visualized in the power spectrum of all EEG channels, more focally in the regions where seizures occur, or in adjacent regions (Fig. 4).

FIG. 2.

Macroperiodic oscillations (MOs) observed in a 9 months old with tetralogy of fallot on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation are visualized on 12- and 1-hour time scales on color density spectral array (CDSA) but not raw EEG. A, Raw EEG corresponding to a MO crest on CDSA (black arrow), and (B) EEG corresponding to a MO trough on CDSA (grey arrow). C, On CDSA MOs may be visualized on the power spectrogram of all channels (top panel), or more focal, in this case O2 (bottom two panels). Displays represent 6 hours of a 12-hour display (top two CDSA panels) and 30 minutes of a 1-hour display (bottom panel).

FIG. 3.

Seizures in the same patient as Figure 1 on raw EEG and color density spectral array. A, The first seizure (black arrow) occurred 5 hours after macroperiodic oscillations (MOs) arising from the right occipital region. Seizures continue somewhat sporadically. B, MOs continue to oscillate, approximately every 4 minutes in this case.

FIG. 4.

Macroperiodic oscillations (MOs) presenting in three different patients. MOs (black dashed lines) may precede seizures (A), wax and wane (B), and/or occur in the midst of electrographic seizures (C). MOs may be best visualized in the power spectrum of all channels (A) or focally in the regions where seizures occur (Cz in B). In other cases (C), MOs may best visualized best in channels adjacent (F3) where seizures are maximal (T7). Representative seizures are marked with black arrows, and MOs are marked with black dashed line. Color density spectral array displays represent 6 hours of a 12-hour display.

There was a 76% overlap in the observed duration of MOs on CDSA-all of a randomly selected subset (see Supplemental Figure s1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JCNP/A152). The mean duration of MOs was 249 minutes (median, 172; range, 48–654 minutes). The MOs pattern occurred in midst of or preceded recurrent seizures within 12 hours (see figures). Macroperiodic oscillations subsided when recurrent seizures stopped and did not outlast seizures. Across groups, these patterns were morphologically similar, consisting of a peaked oscillatory pattern on CDSA emerging from the EEG background (Fig. 1). Macroperiodic oscillations only occurred on a slow disorganized (73.7%) or a discontinuous/burst suppressed background (26.3%).

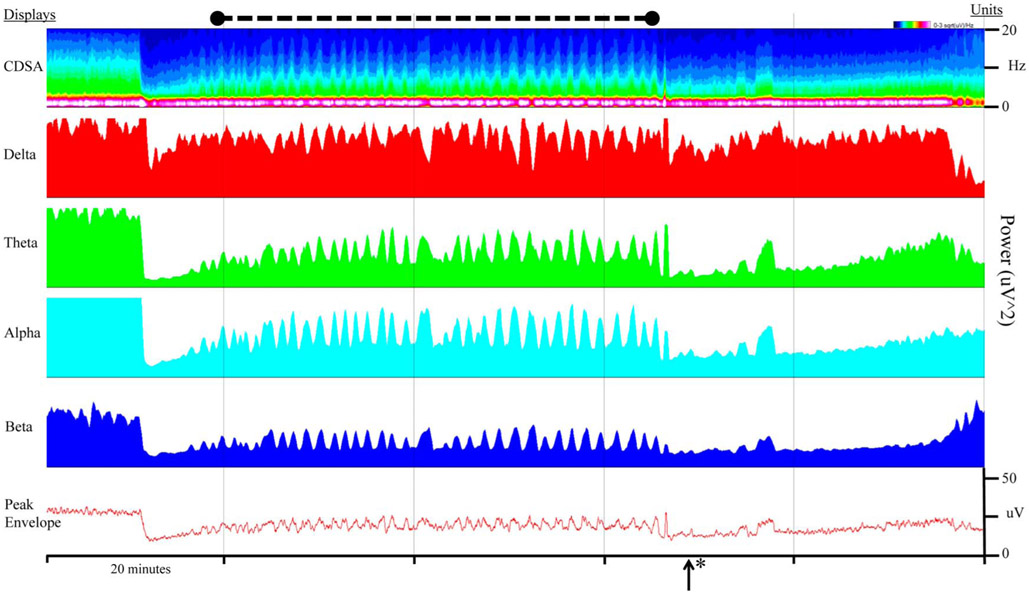

To further characterize MOs, the peaks and troughs were measured based on the Persyst-generated peak envelope with a mean of 10.4 and 8.6 microvolts, respectively (medians of 9.1 and 7.0; ranges of 2.7–23.0 and 1.9–18.7, respectively). The time between peaks was measured on Persyst using visual inspection from crest to crest, with a mean interval of 3 minutes 55 seconds (median, 3:48; range, 2:14–7:41). After recording the delta, theta, alpha, and beta power of four consecutive peaks and troughs (microvolts2), the peak/trough ratio was calculated within a run of MOs. The mean peak/trough ratios and ranges were as follows: delta: mean, 6.7 (range, 1.0–48.3), theta: mean, 5.5 (range, 1.6–33.8), alpha: mean, 4.9 (range, 1.2–29.4), and beta: mean, 2.5 (range, 1.1–10.6). Within any one subject, the interval periodicity and amplitude of the oscillation on CDSA was consistent (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Macroperiodic oscillations (MOs) visualized by power spectrograms and peak envelope. The power spectrogram is displayed for all channels and frequencies (CDSA), as well as delta, theta, alpha, and beta power (μV2) as a 30-second running average. The bottom panel illustrates MOs on a peak envelope display over all channels. MOs (black dashed line) occur in the setting of hypoxic ischemic injury, increased intracranial pressure, and seizures, which resolve with midazolam drip (*). CDSA, color density spectral array.

To address sensitivity and specificity for MOs identification, as well as interrater reliability, two additional board-eligible epileptologists without direct familiarity with MOs reviewed a series of CDSA panels to identify MOs, seizures, both, or neither. The raters had better success and agreement at identifying MOs versus seizures. Macroperiodic oscillations had a sensitivity of 1.000 (1.000, 1.000), specificity of 0.871 (0.753, 0.989), and a kappa score of 0.778 (0.542, 1.000) (P < 0.0001). The sensitivity of seizure detection was 0.531 (0.358, 0.704) and specificity of 0.318 (0.124, 0.5128) with a kappa value of 0.700 (0.441, 0.956) (P < 0.001). The positive predictive value for MOs was 0.852 (0.718, 0.986) compared with 0.531 (0.358, 0.704) for seizures.

In the MOs group, 100% (38/38) of EEGs had seizures, as compared with 22.5% (74/329) in the non-MOs group (P < 0.001). Patients with MOs had recurrent seizures requiring multiple boluses of medications, including phenobarbital, levetiracetam, and fosphenytoin. After receiving sufficient antiseizure medications to abort seizures, MOs also resolved. Medication administration and relationship to the resolution of MOs was not recorded. There was no clear distinguishing difference in seizure focality or semiology between patients with and without MOs.

Among all children monitored, patients with MOs were younger, with a median age of 8.1 days (interquartile range, 1.1–101.8 days), than non-MOs children (median, 207.8 days; interquartile range, 4.1–3,269.7 days) (P < 0.001). The median age of children without MOs, but with seizures was 34 days, which was significantly older than those children with MOs (P < 0.05). Patients with MOs were less likely to have any prior medical conditions (P < 0.05), particularly preexisting neurologic conditions (P < 0.01). The four patients with MOs and premorbid neurologic conditions had genetic/metabolic diagnoses. There were no differences in sex or ICU location of monitoring (Table 1). Patients with MOs were more likely to be admitted for TBI (15.8 vs. 4.9%; P < 0.01) and have clinical seizures as the indication for EEG monitoring (42.1 vs. 15.8%; P < 0.001). Patients without MOs were more likely to have characterization of events or spells as the indication for monitoring (8.3 vs. 31.9%; P < 0.01).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Data of Patient With MOs and Control Subjects Who had Continuous EEG Monitoring During the Same Period

| MO Group, n = 38 | Controls, n = 329 | Significance, P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.53 | ||

| Male (%) | 21 (55.3) | 164 (49.9) | |

| Female (%) | 17 (44.7) | 165 (50.1) | |

| Age (median), days (IQR) | 8.1 (1.1–101.8) | 207.8 (4.1–3,269.7) | <0.001 |

| EEG duration, hours (SD) | 68.1 (41.8) | 42.9 (39.9) | <0.01 |

| Seizures (%) | 38 (100) | 74 (22.6) | <0.0001 |

| Indication for EEG (%) | |||

| CA/resp failure | 1 (2.6) | 39 (11.9) | 0.084 |

| Neonatal encephalopathy | 3 (8.3) | 45 (13.7) | 0.60 |

| Encephalopathy | 4 (10.5) | 55 (16.7) | 0.33 |

| Clinical seizures | 16 (42.1) | 52 (15.8) | <0.001 |

| TBI | 6 (15.8) | 16 (4.9) | 0.007 |

| Characterize events | 3 (8.3) | 105 (31.9) | 0.002 |

| ECMO | 5 (14) | 17 (5.2) | 0.053 |

| Location (ICU) | 0.29 | ||

| CICU (%) | 7 (18.4) | 47 (14.3) | |

| NICU (%) | 15 (39.5) | 99 (30.1) | |

| PICU (%) | 16 (42.1) | 183 (55.6) | |

| Premorbid condition | 0.042 | ||

| Yes (%) | 12 (31.6) | 161 (48.9) | |

| No (%) | 26 (68.4) | 168 (51.1) | |

| Neurologic premorbid condition | <0.01 | ||

| Yes (%) | 4* (10.5) | 110 (33) | |

| No (%) | 34 (89.5) | 219 (67) |

Significant P values are in bold.

The four patients with neurologic premorbid condition had an underlying genetic/metabolic condition that may affect the central nervous system.

CA, cardiac arrest; CICU, cardiac intensive care unit; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; MO, macroperiodic oscillation; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Because all children with MOs had seizures, we sought to determine if this pattern represented an independent risk for seizure or was a marker of other known factors associated with increased risk of seizures. In a multiple logistic regression, the presence of MOs was associated with an increased risk for seizure (odds ratio, 227 [13.7–3,780]; P < 0.0001) when age, premorbid neurologic conditions, and TBI were included in the model.

DISCUSSION

In this descriptive, observational study, we have identified a novel EEG periodic pattern on the power spectrogram. We refer to this phenomenon as MOs, as the pattern occurs over a more “macro” time scale on QEEG CDSA and is not visible on traditional, raw EEG tracing (Fig. 2). Macroperiodic oscillations occur at regular, predictable intervals at an average of 0.004 Hz (3 minutes 55 seconds) that is stable within subjects and has an unvarying magnitude (oscillation) as determined by visual inspection. Macroperiodic oscillations can be visualized in the power spectrogram of individual frequencies, as well as the peak envelope (Fig. 5). All patients with MOs had seizures compared with only 22.5% of children without MOs. The proportion of electrographic seizures in our non-MOs population of critically ill pediatric patients is consistent with prior reports.1,18

Inclusion in the study required 100% agreement for the presence of MOs between the core reviewers on the CDSA of any channel. Overall, there was a 76% overlap in the start and stop times between the three reviewers on a standardized review of CDSA-all (see Supplemental Figure s1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JCNP/A152). This is better agreement than has been reported for marking the on and off times of seizures on raw EEG in critically ill adults.19 To establish sensitivity, specificity, and interrater reliability, two additional epileptologists who were not part of the study team reviewed the CDSA-all for the presence of MOs, seizures, or neither. The reviewers had a higher sensitivity and specificity for MOs than seizures. The sensitivity and specificity for seizures was similar to seizure identification on QEEG-only in the adult intensive care unit9 and a bit lower than studies of pediatric epileptologists and ICU providers; however, more training and CDSA panels were provided for those studies.12,14 Kappa agreement was stronger for MOs than for seizures, likely related to the periodic and repetitive nature of MOs compared with seizures.

Patients with MOs were younger and tended to be previously healthy, presenting with new neurologic injuries (Table 1). Younger patients have a higher risk of seizures in general; however, patients with MOs were still significantly younger than non-MOs patients with seizures. Multivariable modeling of known risk factors for seizures, including age, TBI, and neurologic premorbid conditions, found MOs to have far greater odds of seizures occurring on EEG. The relationship between MOs and seizures does not indicate a causal relationship, but MOs appear to be an independent predictor of seizure risk. Similarly, the presence of periodic or rhythmic discharges on raw EEG has been used as a marker of higher risk of seizures,20,21 and epileptiform abnormalities and clinical factors are associated with an increased risk of seizures in critically ill adults.22,23 On raw EEG, periodic and generalized discharges may guide the duration of EEG monitoring but are not commonly used to guide treatment because they may occur independently of seizures.20,24 Further research is needed to identify whether MOs possess a superior ability to forecast seizures in which case their presence could lead to changes in clinical management.

Macroperiodic oscillations occurred more commonly in previously healthy patients without comorbidities, particularly those without a history of premorbid neurologic conditions (Table 1). These included patients whose EEG indication was TBI and ECMO. Traumatic brain injury and ECMO may cause a heterogenous range of focal, diffuse, and hypoxic ischemic brain injuries; thus, the neuroantatomical relationship between MOs and acquired brain injury remains unclear.

The neurophysiologic generator of these slow rhythmic oscillations is unclear. Macroperiodic oscillations resemble a phase-amplitude coupling phenomenon, in which faster frequency activity occurs at a preferred phase (e.g., at the crest or trough) of a slower modulatory oscillation. Phase-amplitude coupling is a general descriptor that captures a range of electrophysiological phenomena, including burst suppression, epileptiform activity in sleep, neonatal delta brush, and other neural oscillations.25-27 However, the time scales involved in these phenomena are quite diverse, and hence, their underlying mechanisms may be different. Thus, although MOs may broadly fall in the category of phase-amplitude coupling, questions about their specific dynamics and underlying generative mechanisms remain unclear.

Macroperiodic oscillations have a similar morphology as seizures on CDSA and can be visualized in the power spectrogram of all EEG channels but may be even more apparent in the regions where seizures occur (Figures 4B and 4C). Given the similar morphology, and spatial and temporal relationship to seizures, MOs may be on the spectrum of seizures with a similar generator. Macroperiodic oscillations might then represent electrophysiologic perturbations resting at a subthreshold level of recognition on traditional raw EEG. Macroperiodic oscillations resolved when seizures stopped, often following sufficient medication, which may also support a similar pathophysiology. Escalating bolus treatments, typically with phenobarbital or fosphenytoin, lead to the resolution of seizures and MOs with improved EEG variability. If MOs have a similar cellular or network generator as seizures,28-30 then the presence of MOs would have implications for the metabolic function of the affected region similar to periodic discharges or the ictal–interictal continuum. Studies of periodic discharges on raw EEG have identified increased tissue oxygen consumption31 and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography hypermetabolism in these patients.32 In contrast, MOs periodicity occurs over a longer time scale than seizures and periodic discharges with similarities to other slow rhythms in the brain, which are long appreciated as critical to normal brain function.33,34 Macroperiodic oscillations, however, occur at less than 0.01 Hz, which is an order of magnitude slower than previously described. Further investigation is needed to understand the mechanism of MOs and whether this pattern could represent a biomarker of emerging epileptogenic network dysfunction.

Finally, it is unclear what the relationship between MOs and neurodevelopment is. Macroperiodic oscillations tended to occur in younger children; however, it did occasionally occur in older patients including an adolescent. The stability of an EEG phenomenon over such a wide range of ages is inconsistent with known developmental patterns on EEG. A broad range of ages, particularly adults, is required for further quantitative investigation to understand the developmental implications of this pattern.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the observational nature relies upon standard cEEG monitoring with the discovery of the MOs phenomenon during routine clinical care. The timing of EEG monitoring initiation relative to seizures was not standardized. Therefore, we were not able to reliably assess the precise timing of MOs relative to seizures or establish any causal relationship, except to say that when we observed MOs, we subsequently observed seizures. Second, MOs were identified based on visual inspection of the CDSA with the non-MOs, “control” population being one of convenience in which clinicians requested EEG. Although MOs were not observed in many children, it is possible that MOs are not a binary phenomenon, and with more advanced spectral analyses, “mild MOs” may occur in patients with seizures or acquired brain injuries that were not readily apparent during routine clinical review of the CDSA. Additionally, MOs ceased with seizures following antiseizure medications; however a causal relationship cannot be drawn as the relative timing of MOs and medications was not systematically studied. Finally, this study was focused on describing the MOs phenomenon based on initial clinical data and EEG indications. The relationship between MOs and neuroimaging findings, ultimate clinical diagnosis, or outcomes has not yet been identified.

In conclusion, here we describe a novel pattern on the CDSA panel of our QEEG that is associated with electrographic seizures. This pattern, termed MOs, is defined as an oscillating, slow periodic pattern. This phenomenon holds high interrater reliability, and if validated further, it could serve as EEG biomarker of neurologic injury or to forecast a high probability of seizures. Further studies are needed to establish true prevalence and sensitivity of MOs for identifying seizures, as well as the anatomy and pathophysiology of this pattern. Further investigation of these oscillations, which occur at a frequency lower than previously detected, has the potential to provide insights into the brain’s network communication and the pathophysiology of brain injury and seizures.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Kendall Sputo for her support with data collection.

Funding support from Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR002345 (R. M. Guerriero and S. Ching).

Footnotes

The authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Presented in part at the American Clinical Neurophysiology Society Meeting, Las Vegas, 2019.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.clinicalneurophys.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abend NS, Arndt DH, Carpenter JL, et al. Electrographic seizures in pediatric ICU patients: cohort study of risk factors and mortality. Neurology 2013;81:383–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Payne ET, Zhao XY, Frndova H, et al. Seizure burden is independently associated with short term outcome in critically ill children. Brain 2014;137:1429–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raspall-Chaure M, Chin RF, Neville BG, Scott RC. Outcome of paediatric convulsive status epilepticus: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:769–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferro MA, Chin RFM, Camfield CS, Wiebe S, Levin SD, Speechley KN. Convulsive status epilepticus and health-related quality of life in children with epilepsy. Neurology 2014;83:752–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Topjian AA, Gutierrez-Colina AM, Sánchez SM, et al. Electrographic status epilepticus is associated with mortality and worse short-term outcome in critically ill children. Crit Care Med 2013;41:210–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chin RF, Neville BG, Peckham C, Bedford H, Wade A, Scott RC. Incidence, cause, and short-term outcome of convulsive status epilepticus in childhood: prospective population-based study. Neurology 2006;368:222–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herman ST, Abend NS, Bleck TP, et al. Consensus statement on continuous EEG in critically ill adults and children, part I: indications. J Clin Neurophysiol 2015;32:87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang JH, Sherill GC, Sinha SR, Swisher CB. A trial of real-time electrographic seizure detection by neuro-ICU nurses using a panel of quantitative EEG trends. Neurocrit Care 2019;31:312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haider HA, Esteller R, Hahn CD, et al. Sensitivity of quantitative EEG for seizure identification in the intensive care unit. Neurology 2016;87:935–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lalgudi Ganesan S, Stewart CP, Atenafu EG, et al. Seizure identification by critical care providers using quantitative electroencephalography. Crit Care Med 2018;46:e1105–e1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akman CI, Micic V, Thompson A, Riviello JJ Jr. Seizure detection using digital trend analysis: factors affecting utility. Epilepsy Res 2011;93(1):66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Topjian AA, Fry M, Jawad AF, et al. Detection of electrographic seizures by critical care providers using color density spectral array after cardiac arrest is feasible. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2015;16:461–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quint SR, Michaels DF, Hilliard GW, Messenheimer JA. A real-time system for the spectral analysis of the EEG. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 1989;28:11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pensirikul AD, Beslow LA, Kessler SK, et al. Density spectral array for seizure identification in critically ill children. J Clin Neurophysiol 2013;30:371–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fung FW, Topjian AA, Xiao R, Abend NS. Early EEG features for outcome prediction after cardiac arrest in children. J Clin Neurophysiol 2019;36:349–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCoy B, Sharma R, Ochi A, et al. Predictors of nonconvulsive seizures among critically ill children. Epilepsia 2011;52:1973–1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arndt DH, Lerner JT, Matsumoto JH, et al. Subclinical early post-traumatic seizures detected by continuous EEG monitoring in a consecutive pediatric cohort. Epilepsia 2013;54:1780–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abend NS, Wusthoff CJ, Goldberg EM, Dlugos DJ. Electrographic seizures and status epilepticus in critically ill children and neonates with encephalopathy. Lancet Neurol 2013;12(12):1170–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tu B, Young GB, Kokoszka A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy between readers for identifying electrographic seizures in critically ill adults. Epilepsia Open 2017;2:67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodriguez Ruiz A, Vlachy J, Lee JW, et al. Association of periodic and rhythmic electroencephalographic patterns with seizures in critically ill patients. JAMA Neurol 2017;74:181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoo JY, Rampal N, Petroff OA, Hirsch LJ, Gaspard N. Brief potentially ictal rhythmic discharges in critically ill adults. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:454–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Struck AF, Osman G, Rampal N, et al. Time-dependent risk of seizures in critically ill patients on continuous electroencephalogram. Ann Neurol 2017;82:177–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Struck AF, Ustun B, Ruiz AR, et al. Association of an electroencephalography-based risk score with seizure probability in hospitalized patients. JAMA Neurol 2017;74:1419–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauerschmidt A, Rubinos C, Claassen J. Approach to managing periodic discharges. J Clin Neurophysiol 2018;35:309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mukamel EA, Pirondini E, Babadi B, et al. A transition in brain state during propofol-induced unconsciousness. J Neurosci 2014;34:839–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shibata T, Otsubo H. Phase-amplitude coupling of delta brush unveiling neuronal modulation development in the neonatal brain. Neurosci Lett 2020;735:135211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanhatalo S, Palva JM, Holmes MD, Miller JW, Voipio J, Kaila K. Infraslow oscillations modulate excitability and interictal epileptic activity in the human cortex during sleep. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:5053–5057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McNamara JO. Cellular and molecular basis of epilepsy. J Neurosci 1994;14:3413–3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blumenfeld H. Cellular and network mechanisms of spike-wave seizures. Epilepsia 2005;46(suppl 9):21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheybani L, Birot G, Contestabile A, et al. Electrophysiological evidence for the development of a self-sustained large-scale epileptic network in the kainate mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci 2018;38:3776–3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Witsch J, Frey H-P, Schmidt JM, et al. Electroencephalographic periodic discharges and frequency-dependent brain tissue hypoxia in acute brain injury. JAMA Neurol 2017;74:301–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Struck AF, Westover MB, Hall LT, Deck GM, Cole AJ, Rosenthal ES. Metabolic correlates of the ictal-interictal continuum: FDG-PET during continuous EEG. Neurocrit Care 2016;24(3):324–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aladjalova NA. Infra-slow rhythmic oscillations of the steady potential of the cerebral cortex. Nature 1957;179:957–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buzsáki G, Wang X-J. Mechanisms of gamma oscillations. Annu Rev Neurosci 2012;35:203–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.