Abstract

Biodegradable cellular and acellular scaffolds have great potential to regenerate damaged tissues or organs by creating a proper extracellular matrix (ECM) capable of recruiting endogenous cells to support cellular ingrowth. However, since hydrogel-based scaffolds normally degrade through surface erosion, cell migration and ingrowth into scaffolds might be inhibited early in the implantation. This could result in insufficient de novo tissue formation in the injured area. To address these challenges, continuous and microsized strand-like networks could be incorporated into scaffolds to guide and recruit endogenous cells in rapid manner. Fabrication of such microarchitectures in scaffolds is often a laborious and time-consuming process and could compromise the structural integrity of the scaffold or impact cell viability. Here, we have developed a fast single-step approach to fabricate colloidal hydrogels, which are made up of randomly packed human serum albumin-based photo-cross-linkable microparticles with continuous internal networks of microscale voids. The human serum albumin conjugated with methacrylic groups were assembled to microsized aggregates for achieving unique porous structures inside the colloidal gels. The albumin hydrogels showed tunable mechanical properties such as elastic modulus, porosity, and biodegradability, providing a suitable ECM for various cells such as cardiomyoblasts and endothelial cells. In addition, the encapsulated cells within the hydrogel showed improved cell retention and increased survivability in vitro. Microporous structures of the colloidal gels can serve as a guide for the infiltration of host cells upon implantation, achieving rapid recruitment of hematopoietic cells and, ultimately, enhancing the tissue regeneration capacity of implanted scaffolds.

Introduction

Opening a new path to the effective delivery of biological factors (e.g., stem cells, growth factors, drugs, small interfering RNA (siRNA), and microRNA) to injured tissue sites, engineered biodegradable scaffolds are capable of creating suitable extracellular matrices (ECMs) for implanted cells, thus facilitating and enhancing tissue regeneration.1,2 Implantable and biodegradable scaffolds developed to date have utilized numerous natural and synthetic biomaterials; polyester urethane-based porous synthetic scaffolds loaded with siRNA used for promoting in vivo angiogenesis3,4 and fibrin-based scaffolds for enhanced cell survival after transplantation, reduction of infarct expansion, and development of neovasculature in the ischemic myocardium5−7 are some examples. A major challenge in successful long-term integration of scaffolds within the host tissue is enabling the scaffold to rapidly interface with the existing host microenvironment and cellular architecture while delivering numerous biological factors (e.g., growth factors and drug molecules) to target cells.8 While several studies have focused on fabricating biomaterials with prevascularized structures or delivering growth factors that induce the growth of endothelial cells at the implant site,9,10 the fabrication process is often not straightforward, thus limiting the usability of the scaffold.11 Moreover, delivering growth factors to the injured site has been limited by the insufficient half-life and instability of these biomolecules, thus impacting the long-term effectiveness of implanted scaffolds.12,13

Among various biomolecules, albumin, one of the most abundant water-soluble proteins found in blood plasma (40–50 mg/mL, 65–70 kDa) due to its negatively charged surface, possesses an ability to bind to various active biological substances (e.g., vitamins, hormones, fatty acids, ions, and drugs) and can transport these materials to the required tissues by enhancing the in vivo half-life of the bound active substances.14 In addition, albumin is capable of binding to inflammation-inducing substances and free radicals, taking part in antioxidative and anti-inflammatory roles while having minimal immunogenicity and toxicity.15 Albumin also takes part in congenital endothelial stabilization and acts as an essential factor for the growth and function of various cells (e.g., endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells).16,17 Consequently, fabricating albumin-based biodegradable scaffolds can provide unique advantages to tissue regeneration upon implantation since various growth factors and active substances can be incorporated into the implantable scaffold with improved half-lives and increased concentrations. Furthermore, albumin can be self-assembled into aggregates that can pack into a 3D cubic lattice with abundant cavities, i.e., porous channels, in specific conditions.18 This unique self-assembly property and the biological nature of albumin can be useful for creating continuous and microsized internal networks inside scaffolds.19,20 Accordingly, albumin-based hydrogels have recently emerged as promising scaffolds for bone,21 cardiac regeneration,22 and wound healing.23 The fabrication method typically involves thermal or pH-induced albumin gelation or chemically cross-linking with other conjugates.19,24 These methods, however, are time-consuming, provide suboptimal cell attachment, and could cause immunogenic reactions upon implantation. Moreover, recent studies have mostly focused on employing bovine serum albumin (BSA), which does not accurately recapture the human serum albumin (HSA) protein sequence and implications for tissue regeneration in humans.24

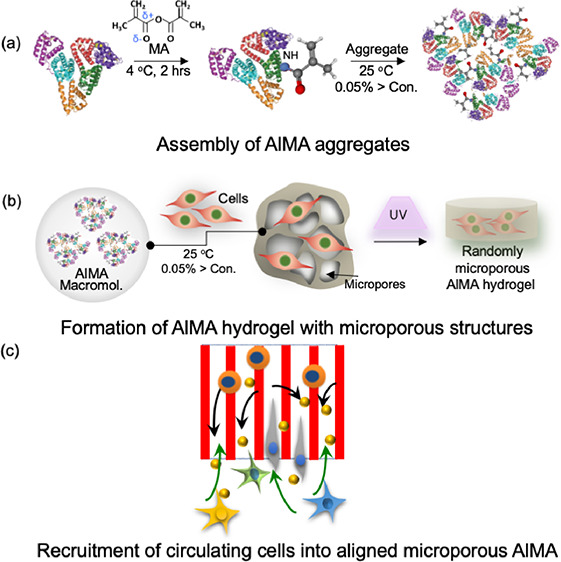

Here, we introduce a human albumin-based colloidal hydrogel, namely, packed photo-cross-linkable human serum albumin methacryloyl (AlMA) microparticles, to improve cell retention and survivability within thick scaffolds. Specifically, albumin from human serum can be conjugated with methacrylic functional groups to form AlMA, which can then self-assemble into hydrogels upon UV and visible light exposure. Furthermore, the physical and mechanical properties of AlMA hydrogels could be tuned by the degree of methacrylation (DM) and the concentration of AlMA. Consequently, the formed AlMA hydrogel with continuous and microscale internal networks can serve as a guide for infiltrated cells to achieve rapid recruitment and allow for the ingrowth of circulating cells as a “regenerative pod,” unlike any hydrogel with randomly formed porous structures. In the future, the straightforward and highly tunable fabrication process of AlMA biomaterials could be leveraged with recent additive manufacturing technologies, namely, in situ bioprinting, to rapidly create nanocarrier- and growth factor-conjugated scaffolds with longer half-lives, geometries customized to the defect size, and an enhanced functionality in inducing angiogenesis and tissue regeneration.

Results and Discussion

Fabrication of the Photo-Cross-Linkable AlMA Aggregates

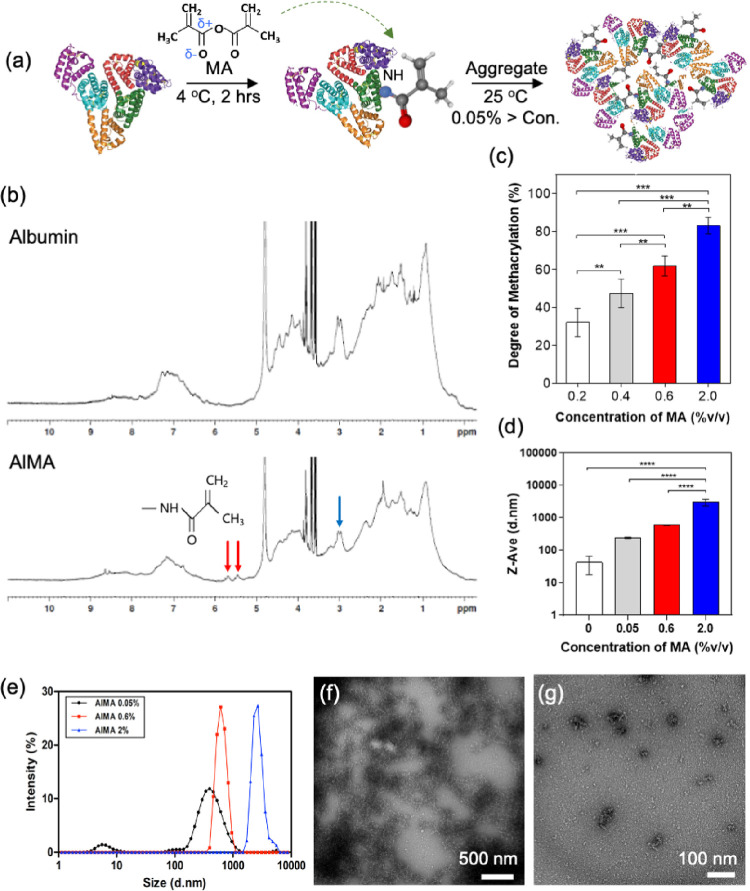

AlMA was synthesized through the nucleophilic substitution reaction, in which electron-rich groups such as thiol (−SH), hydroxyl (−OH), and amino groups (−NH2) on the side chain of amino acids donate electron pairs to the carbonyl carbon of MA to create acyl derivatives. Among other moieties, the amine groups in lysine predominate the overall reaction due to their steric accessibility within the albumin structure.25 Therefore, methacryloyl groups were covalently conjugated to free amine groups in recombinant human serum albumin (Figure 1a). It is important to note that maintaining subneutral-pH and low-temperature conditions (<4 °C) is essential to prevent protein denaturation and degradation. 1H NMR spectra verified the conjugated methacryloyl groups to the AlMA. Due to the strong water-attracting property of albumin, the baseline of the spectrum was not smooth enough to reliably quantify the molecules through integrating the area under the curve. Methacrylic modification of albumin was therefore confirmed after manual adjustment of the baseline and phase correction. As shown in Figure 1b, we observed two newly generated peaks at 5.4 and 5.7 ppm (red arrows) in the AlMA spectrum, which were created by the protons in the methacrylate vinyl groups. Simultaneously, a reduction in methylene of the lysine was observed at the 2.9 ppm signal (blue arrow), indicating successful conjugation.

Figure 1.

Light cross-linkable human serum AlMA aggregates. (a) Schematic diagram showing the fabrication process of AlMA aggregates in presence of methacrylate and proper environmental conditions (temperature, ∼4 °C; incubation time, ∼2 h). Reprinted with permission from Larsen, Kuhlmann, Hvam, and Howard. Copyright 2016 National Library of Medicine. (b) NMR data of pristine albumin and AlMA. (c) Synthetized AlMA aggregates exhibit various degrees of methacrylation at different concentrations of MA added during synthesis. (d) Hydrodynamic diameters and (e) Gaussian distribution of size in AlMA aggregate particles at various concentrations of MA (% v/v) added during synthesis. (f, g) Cryo-TEM images of AlMA aggregates (6000× and 12,000× magnification).

Next, we set out to tune the mechanical and physical properties of the AlMA hydrogel by tuning the concentration of MA from 0.05 to 2.0% (v/v), thus achieving various degrees of methacrylation as shown in Figure 1c. As a result, we were able to achieve a wide range of DM (∼35 to 82%) in proportion to the concentration of MA, providing a potential to tune the stiffness of AlMA hydrogels. However, a DM of more than 82.1 ± 3.0% (equivalent to 2.0% v/v MA) was not achievable due to the denaturation of the albumin molecules in the presence of high-concentration MA (data not presented), which could be pertained to the denaturing effect of the adsorption of methacryloyl groups onto the protein structure via strong hydrophobic interactions.26 To sum up, the degree of methacrylation of AlMA used for the experiments were either 0.6% MA (∼61.5% DM) or 2% MA (∼83.1% DM), and two different AlMA polymer concentrations (10 or 20% w/v) within each degree of methacrylation were used (Table 1).

Table 1. Sample Names, % Volume of Methacrylic Anhydride Used, Degree of Methacrylation, and AlMA Polymer Concentrations Used for the Experiments.

| AlMA

preparation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| sample name | % volume methacrylic anhydride (MA) | degree of methacrylation (%) | AlMA polymer conc. (%) |

| 0.6/10 | 0.6 | 61.5 | 10 |

| 0.6/20 | 0.6 | 61.5 | 20 |

| 2/10 | 2 | 83.1 | 10 |

| 2/20 | 2 | 83.1 | 20 |

Next, we optimized albumin concentration and the incubation conditions to guide the self-assembly of AlMA aggregates at a neutral pH similar to that of biological environments. Albumin is a natural colloidal particle that maintains the colloidal osmotic pressure of blood.27 Constructing this colloidal environment by dispersing AlMA molecules in a solution forms the AlMA colloidal solution and is followed by the formation of self-assembled aggregates.28 The formation of albumin aggregates was observed at high albumin concentrations (>0.05%) at 25 °C for 1 h (data not shown). Furthermore, the conjugated hydrophobic methacryloyl groups on the albumin molecules may take part in altering the amphiphilic nature of albumin, which could affect the formation of the self-assembled aggregates and their sizes.29 We then demonstrated the effects of the DM on the self-assembled AlMA aggregates. Specifically, AlMA aggregates formed under different DM conditions ranged from ∼12 to 2000 nm in size (Figure 1d). The size of the aggregates formed at high (2.0%) and medium (0.6%) DMs were increased (Figure 1e) in comparison to low-DM (0.05%) and pristine albumin aggregates due to the increased hydrophobicity of AlMA molecules upon increased methacryloyl substitutions. The increased hydrophobicity might have induced strong hydrophobic interactions among AlMA molecules in an aqueous environment, which could have resulted in the creation of more large aggregates with increased diameters.30 The formation of AlMA aggregates at a high DM was visually confirmed by cryo-transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM), applying the negative staining with uranyl acetate solution (Figure 1f,g). At high concentration, we confirmed continuous clustered networks (Figure 1f) and individual aggregates were observed at a low concentration of aggregates (Figure 1g), which is in agreement with the previously reported TEM results.31

Development and Characterization of AlMA Hydrogels

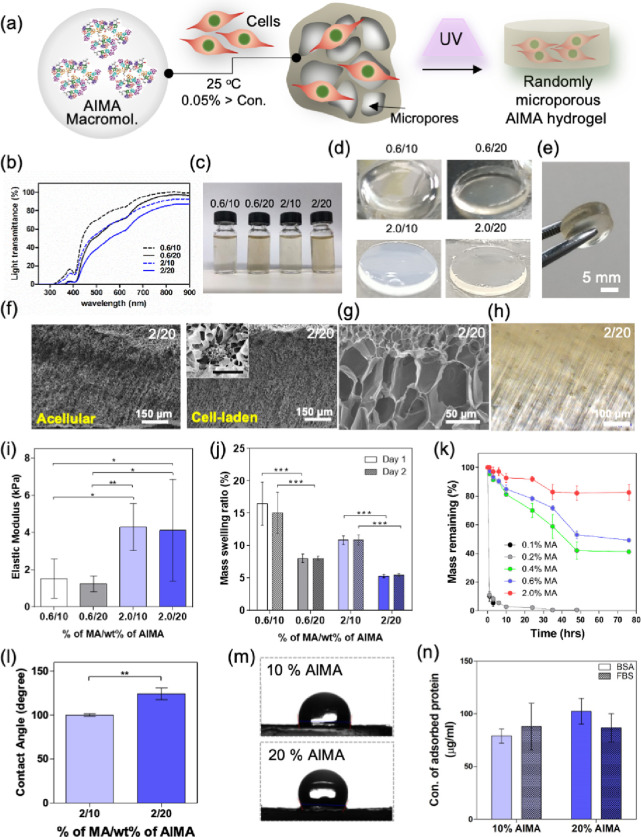

We first studied the characteristics of hydrogels formed upon photo-cross-linking AlMA colloidal particles in the presence and absence of cells (Figure 2a). Upon UV exposure, the methacryloyl groups in the self-assembled structures were cross-linked, resulting in a randomly packed colloidal hydrogel with continuous and microporous networks. Prepolymer solutions fabricated at high DMs or high AlMA polymer concentrations exhibited significantly decreased transmittance and increased turbidity at 360–480 nm UV wavelengths (Figure 2b,c). AlMA hydrogels fabricated at high DMs showed higher opacity than medium-DM AlMA hydrogels for both low and high AlMA concentrations (Figure 2d). This may be due to increased size of aggregates at higher degrees of MA (Figure 1d). Following UV exposure optimization, large-sized AlMA hydrogels (>5 mm) could be fabricated for structurally robust and easy to handle implantable units for surgery (Figure 2d,e). Interestingly, when the AlMA hydrogel was observed under a brightfield microscope, a unique internal pore structure different from GelMA hydrogel was confirmed. The internal patterning of the hydrogel occurred according to the direction of the UV for cross-linking (Figure 2f,g). This internal patterning phenomenon occurred regardless of the presence or absence of cells (Figure 2h and Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Physical characterization of AlMA hydrogels. (a) Schematic diagram showing the process of integrating cells with AlMA colloidal solution to achieve UV cross-linked hydrogels with random microporosity. AlMA aggregates formed during this process act as ECM binding sites for the cells. Figure compiled and drawn by author. (b) Percentage of light transmittance of AlMA aggregates solution at two different AlMA concentrations (10 and 20) and different degrees of MA (0.6 and 2). The light transmitted through the different prepolymer solutions of AlMA compared with PBS as blank was used to calculate the percentage of light transmittance. AlMA aggregate-laden solutions of different MA and AlMA concentrations (c) before and (d) after being photo-cross-linked upon UV exposure. (e) UV-cross-linked free-standing and robust AlMA hydrogels (The diameter and thickness are 8 and 5 mm, respectively). (f) SEM images of the acellular and NIH3T3 cell-laden AlMA hydrogels. (g) Magnified SEM image of the micropores created within the cross-linked AlMA hydrogels. (h) Cross-sectional phase contrast images of AlMA hydrogels with cells. (i) Elastic modulus of AlMA hydrogels at various degrees of MA and AlMA concentrations. (*P < 0.05). (j) Swelling behavior of AlMA hydrogel masses at various degrees of MA and AlMA concentrations. (***P < 0.0001; n = 5). (k) Degradation behavior of AlMA hydrogels with various DMs was studied by measuring the ratio of the remaining hydrogel mass over the time of culture compared with the initial mass on day 0. The percentage of mass remaining was calculated by comparing the dry weight of the samples after making the hydrogel with the dry weight of the hydrogel remaining after degradation. (l) Contact angle measurement of 10 and 20% AlMA high-DM hydrogels, (DM = 2%, *P < 0.05; n = 3). (m) Photographs of water drop on the surface of 10 and 20% AlMA hydrogels. (n) Concentrations of adsorbed BSA and proteins to 10 and 20% AlMA hydrogels.

To study the mechanical tunability of AlMA hydrogels, we varied the DM (0.6 to 2.0%) and observed an increase in the elastic modulus up to ∼5 kPa at high DMs and ∼2 kPa at low DMs (Figure 2i). The elastic modulus of the 10% w/v AlMA hydrogels was comparable to 4 mg/mL collagen hydrogels (control 1) (Figure S2), which is commonly used for tissue engineered scaffolds (e.g., bone, cartilage, skin, vascular grafts, etc.). Increasing the concentration of AlMA, however, showed little effect on the elastic modulus possibly due to the reduction of transmittance followed by the inhibition of PI free radicals and, eventually, a reduction in cross-linking density of the hydrogels (Figure 2b). A controllable degradation profile in an engineered polymer is a crucial factor for balanced tissue formation and the sustained release of bioactive compounds. Albumin has been proposed as an injectable delivery vehicle for various drugs and can be degraded by collagenase and other digestive proteases such as papain or trypsin.32 To study the degradation behavior of AlMA hydrogels, we selected collagenase type 2 as a representative tissue dissociation enzyme (TDE). We observed that degradation behavior and hydrogel swelling were strongly affected by the UV cross-linking density (Figure 2j,k). Most AlMA hydrogels showed equilibrium swelling behavior within 24 h but afterward exhibited high swelling ratios (5–15%) due to high microporosity and absorption of water. Similarly, increasing AlMA polymer concentration and DM resulted in a significant reduction in swelling behavior due to high UV cross-linking density and the reduction of porosity (Figure S3). AlMA hydrogels with low DM (0.1 and 0.2%) exhibited rapid degradation behavior up to ∼90% degradation within 1 h of incubation (Figure 2k), while medium-DM hydrogels (0.4–0.6%) degraded to ∼50% after 72 h of incubation and high-DM hydrogels (2.0%) exhibited 80% remaining mass over the same period. Consequently, high-DM hydrogels with improved elastic moduli and reduced swelling behavior showed relatively slower degradation and were therefore selected for the following analyses.

Another interesting physical property of albumin is that it strongly binds with various biological substances such as growth factors, hormones, and fatty acids.33 Wettability has been shown to determine adsorption attributes such as kinetics, quantities, deformation, and reversibility. After measuring the contact angle of water, one can estimate the hydrophilicity, wettability, adhesiveness, and surface free energy of the AlMA hydrogels (Figure 2l). For the comparative analysis, two common hydrogels used in tissue engineering, 10% w/v PEGDA and GelMA hydrogels, were studied (Figure S4). The contact angles of AlMA hydrogels increased in proportion to the increment of the concentration of AlMA colloidal solution (Figure 2m). The 20% w/v AlMA hydrogel showed the highest angle of 124.0 ± 26.6° among the three polymers (65.5 ± 0.5° for GelMA hydrogel and 24.1 ± 0.1° for PEGDA hydrogel) as shown in Figure S4. The surface hydrophilicity can be estimated to be higher in the order of PEGDA > GelMA > low-concentration AlMA > high-concentration AlMA. According to our data, wettability and solid-surface free energy were also the lowest for the AlMA hydrogel compared to the PEGDA and GelMA hydrogels. We then observed the dominant interfacial forces from protein adsorption attributes under the influence of surface charge and wettability (Figure 2n and Figure S4c). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were similarly adsorbed on all hydrogels without any significant difference. The GelMA (10% w/v) and AlMA hydrogels with two different concentrations (10 and 20% w/v) showed good adsorption compared with PEG hydrogels. To improve the adsorbed number of proteins on the hydrogel, both hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties that can induce various types of physical interactions, such as electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic intersections between proteins and the surfaces of hydrogels, are required, compared with hydrogels that can only possess highly hydrophilic or hydrophobic properties.

In Vitro Characterization of the AlMA Hydrogels

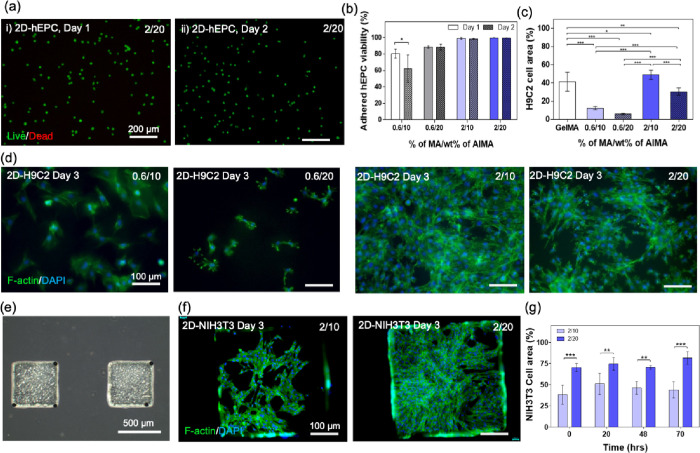

Albumin plays an essential role in transporting conjugated drugs to cells through caveolae-mediated endocytosis, particularly in specialized membrane architectures such as endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells.16,34 Aside from its central role as a functional carrier and ligand-binder in both in vivo and in vitro cellular environments, albumin has proven to be instrumental in alleviating reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced oxidative tissue damage by binding to free radicals as well as providing protection against hydrodynamic stress induced by in vitro vessels (e.g., bioreactors).16 To ensure that AlMA hydrogels provide favorable ECM for cell proliferation and spreading, we next examined cellular behavior in hydrogels seeded with a representative subset of cell types whose successful culture is dependent on albumin-rich microenvironments such as those found in native blood vessels: human epithelial cells (hEPCs), rat cardiomyoblasts (H9C2), and NIH-3T3 fibroblasts. Unlike collagen or GelMA hydrogels, albumin does not contain cell-binding sites such as Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptides. However, AlMA hydrogels can adsorb and maintain abundant biological molecules, which are excised in the cell culture media or secreted from cells and could improve cellular viability and proliferation. According to our study, 10–20 wt % AlMA hydrogels at high DMs (2.0%) exhibited high levels of seeded cell viability (> ∼95%) (Figure 3a,b). Low-DM (0.6%) hydrogels, on the other hand, exhibited slightly lower viability (∼80%), possibly due to their insufficient stiffness for supporting cell attachment and growth.35 We observed that increasing the DM had a major impact in increasing the elongated cell area on the surface of the AlMA hydrogels (Figure 3c,d). In the case of H9C2 cells, cell spreading in high-DM hydrogels was so significant on day 3 that the formation of interconnected cytoskeleton networks was observed throughout the surface (Figure 3d). Increasing the concentration of AlMA from 10 to 20% w/v led to a reduction in cell adherence and spreading by ∼20 wt % in high-DM hydrogels and ∼5% in low-DM hydrogels (Figure 3c). High-DM % w/v AlMA hydrogels exhibited comparable cellular spreading behavior to 10% w/v GelMA hydrogels (Figure 3c), both of which demonstrated an elastic modulus of ∼5 kPa (Figure S2). With the help of photolithography, AlMA hydrogels can also be micropatterned with various shapes of masks for having a potential to fabricate complex ECM architectures (Figure 3e). NIH-3T3 cells seeded on the micropatterned AlMA hydrogels exhibited great elongation and interconnected cellular networks (Figure 3f and Figure S6). We observed a ∼30% increase in cell area by increasing the concentration of AlMA from 10 to 20% w/v (Figure 3g), and this increase was consistent in 70 h of culture.

Figure 3.

Biological characterization of AlMA hydrogels with cells seeded on top. (a) Live/dead viability assay of hEPCs seeded on the surface of 2/20 AlMA (2% MA, 20% AlMA) hydrogels showing >90% viability on (i) day 1 and (ii) day 2. (b) Quantified viability (ratio of the number of live cells/total cells) of adhered hEPCs on the AlMA hydrogels with various concentrations of AlMA and degrees of MA (*P < 0.05; n = 3). (c) Calculated cellular area for seeded H9C2 cells on AlMA hydrogels (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.0001; n = 6). (d) Fluorescent images of F-actin/DAPI-stained H9C2 cells cultured on 10 and 20% AlMA hydrogels at low and high DMs. (e) Phase contrast images of micropatterned AlMA hydrogel blocks. (f) Fluorescent images of F-actin/DAPI-stained NIH-3T3 cells cultured on 10 and 20% w/v AlMA hydrogels at 2% DM. (g) Calculated cellular area for seeded NIH-3T3 cells on 10 and 20% w/v AlMA hydrogels at 2% DM over a 70 hour culture period (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; n = 4). The 10% AlMA hydrogels used in the analysis had varying DM (27, 36, 51, and 58% DM each corresponding to 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, and 0.6% MA used for the modification).

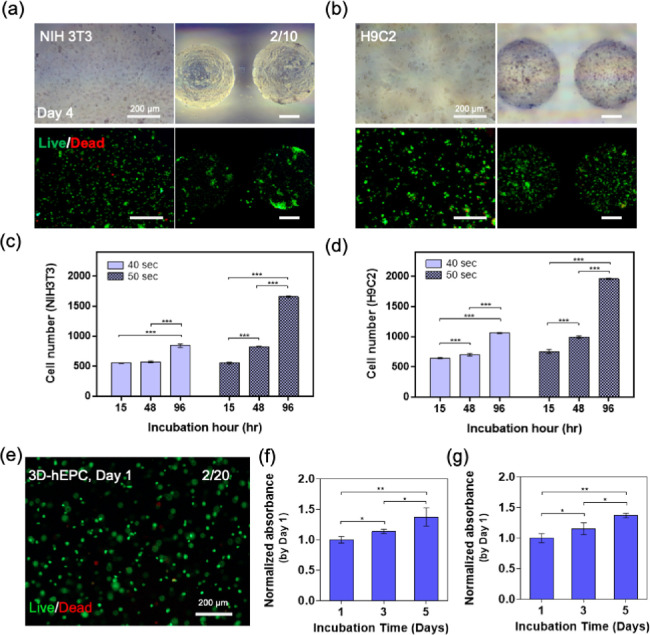

Next, we set out to encapsulate the representative cells (i.e., NIH-3T3, H9C2, and hEPC) into micropatterned AlMA hydrogels to form 3D constructs. Moving from a 2D culture to 3D constructs, photo-cross-linkable hydrogels are expected to exhibit a relative loss in cellular viability due to the mechanical stresses induced by the encapsulation process as well as increased UV exposure duration and PI concentration, which leads to the generation of free radicals.36 We encapsulated NIH-3T3 and H9C2 cells in high-DM 20% w/v AlMA hydrogels and observed a uniform distribution with high viability in micropatterned AlMA hydrogels (Figure 4a,b). To optimize UV exposure for maintaining cell viability, we constructed the hydrogels at two UV exposure durations (40 and 50 s) and measured the number of viable cells over the course of 96 h (Figure 4c,d). At higher UV exposure time, which yielded higher mechanical stiffness (Figure S3), cell-laden AlMA hydrogels showed a significant increase in the number of embedded cells, which suggested that the hydrogel stiffness was well suited to support cell proliferation. hEPC-laden AlMA hydrogels also demonstrated >90% cellular viability over the course of 24 h (Figure 4e and Figure S7). Moreover, encapsulated hMSCs and C2C12 showed an increase in metabolic activity rates up to day 5 (Figure 4f,g).

Figure 4.

Biological characterization of AlMA hydrogels with 3D embedded cells. (a) Phase contrast and live/dead images of NIH-3T3 and (b) H9C2 cell-laden bulk (left) and micropatterned (right) 10% AlMA hydrogels. Live cell number of encapsulated (c) NIH-3T3 and (d) H9C2 in the 10% w/v AlMA high-DM hydrogels. (e) Live/dead image of encapsulated hEPCs in the 20% w/v AlMA high-DM hydrogels on day 1 of culture. Metabolic activity of encapsulated (f) C2C12s and (g) hMSCs in the 20% w/v AlMA high-DM hydrogels (*P < 0.05; n > 3).

AlMA Hydrogels Exhibit Successful Host Invasion and Degradation In Vivo

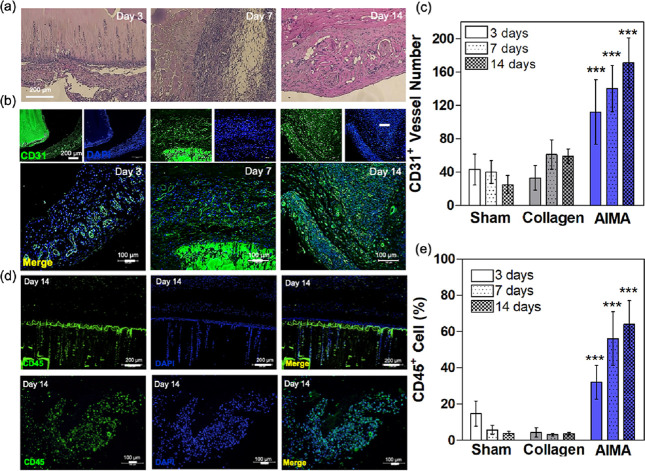

Confirming the viability using various cell types encapsulated in AlMA hydrogels, we next explored the implantability of AlMA hydrogels. In a model of circulating cell invasion, AlMA and collagen (control) hydrogels of identical geometrical properties (cylindrical diameter, 8 mm; thickness, 1 mm) were implanted in the rat dorsal skin subcutaneously. After 14 days of in vivo culture, the AlMA implants exhibited a noticeable amount of host infiltration (Figure 5a). Analysis of explants harvested on day 3 revealed infiltration of circulating cells within the internal pores of AlMA hydrogel and was covered by a thin layer of fibrous capsule at the hydrogel interface (Figure 5a and Figure S8). On day 7, circulating cell infiltration intensity was considerably greater, and AlMA hydrogels were divided into fragments surrounded by collagen fibers as shown with Masson’s trichrome staining (Figure 5a and Figure S9). Additionally, revealing a high number of CD31+ vessels, AlMA hydrogel implants demonstrated neovascularization in the peri-implant area (Figure 5b,c) in comparison with the collagen or sham +conditions (Figure S10). Higher proliferation of vasculature in AlMA hydrogels could be attributed to the migration of macrophages after transplantation, which contributes to endothelial (CD31+) proliferation and may also lead to vascular regeneration-facilitated tissue remodeling.23,37 CD31 plays a role in binding and interaction between leukocytes, endothelial cells, and adjacent endothelial cells. Ligation of CD31 to the leukocyte surface is associated with the activation of functional leukocyte integrin, and leukocyte transmigration throughout the endothelium suggests an affinity CD31 interaction. In other words, hydrogel based on albumin, a major protein in body serum, can rapidly collect circulating cells and has high binding ability.38 Further staining with CD45 after 14 days revealed that the number of leukocytes increased throughout the tissue comprising the peri-implant area (Figure 5d). The quantification revealed that the percentage of CD45+ cells was significantly greater in comparison to the collagen scaffold (Figure 5e).

Figure 5.

In vivo characterization of AlMA hydrogels upon subcutaneous implantation in rats. 20% AlMA high-DM hydrogels were cultured subcutaneously and characterized on days 3, 7, and 14 of in vivo culture. (a) H&E staining of implanted hydrogels and surrounded tissues. (b) Immunohistology images of CD31+ cells (green) and DAPI (blue) in the implanted AlMA hydrogels across different timepoints. (c) Percentage of vessel number across AlMA implants. The number of CD31+ vessel profiles per area were counted (compared with sham group; ***P < 0.005). (d) Immunohistology images stained for CD45+ cells (green) and DAPI (blue) in the implanted AlMA hydrogels. (e) Quantified CD45+ cells across AlMA implants. The number of CD31+ vessel profiles per area were counted (compared with sham group; ***P < 0.005).

Conclusions

In this study, we successfully designed and characterized human serum albumin-based photo-cross-linkable hydrogels (AlMA) that could be used for fabricating tissue-engineered implantable cell-laden constructs. In addition to their microporosity, the proposed AlMA hydrogels showed tunable physical and biodegradable functions that could mimic the biomechanical properties of target ECMs. Moreover, the hydrogel demonstrated a capability to support implant survival with increased survivability in vivo and served as a guide for host infiltration and rapid recruitment of hematopoietic cells. Overall, the results of the proposed AlMA hydrogels suggest a new biomaterial capable of tunable stiffness and degradation, therapeutic delivery to injured sites, and cellular ingrowth for regenerative medicine applications.

Exploiting albumin’s inherently valuable physiological functions such as binding to key biological compounds (e.g., vitamins, hormones, fatty acids, ions, and drugs), nanocarrier- and growth factor- conjugated scaffolds can be fabricated with enhanced half-life, making AlMA potentially suitable for wound closures or wound dressing applications. The high affinity toward numerous biomolecules makes AlMA a great candidate for the delivery of wound healing factors to the injured site. Furthermore, since there are albumin-based products that have already been approved by the FDA, obtaining approval for the clinical use of AlMA is projected to be relatively easier than other biomaterial-based scaffolds. In addition to the hemostatic and wound healing aspect, AlMA would also perform well as a photo-cross-linkable bioink for a wide range of 3D bioprinting applications that have emerged in the past decade. In this regard, rapid fabrication methods targeting large-scale scaffolds with intricate detail yet robust microarchitectures can benefit from using AlMA-based additive bioprinting techniques. Finally, tunability and ease of fabrication of AlMA hydrogels can be applied to the fabrication of geometries customized to the defect size to enable enhanced integration, angiogenesis, and tissue regeneration.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Albumin from human serum (A1653, ≥96%; lyophilized powder), methacrylic anhydride (MA), and 3-(trimethoxysilyl) propyl methacrylate (TMSPMA) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA). Dialysis membrane (Standard Regenerated Cellulose Membrane, Spectra/Por) was purchased from SpectrumLabs (CA, USA). Ultraviolet (UV) light curing system (Omnicure S2000) was purchased from EXFO Photonic Solutions Inc. (Ontario, Canada), and the photomasks with printed patterns used for hydrogel patterning were custom-made from CADart (Washington, USA).

Preparation of Human Serum Albumin Methacryloyl (AlMA)

Human serum albumin methacryloyl (AlMA) was synthesized by substituting amine groups mainly in lysine residues with methacrylic groups as previously described39 with several modifications. Briefly, lyophilized human serum albumin was dissolved in distilled water (pH 7) in 5% w/v concentration at 4 °C and until albumin is completely dissolved. Methacrylic anhydride (MA) was added to the albumin solution at a rate of 200 μL/min to reach the specified target concentration (0.05, 0.2, 0.6, 0.8, 1, and 2% v/v) under constant stirring, and the reaction time was set to 2 h (4 °C) to minimize the precipitation. Then, additional distilled water was added, after which the resulting mixture was dialyzed (pH 6.5–7) using a 12–14 kDa cutoff dialysis membrane for three days. Maintenance of pH is crucial to prevent isoelectric point-induced albumin precipitation at around pH 4.7. The solution was finally lyophilized and stored at −80 °C before the experiments.

Characterization of AlMA

2,4,6-Trinitrobenzenesulfonic Acid Assay (TNBSA)

The degree of methacrylation (DM) of AlMA was calculated using 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid assay (TNBSA) to quantify unreacted free amine groups and the percentage of the number of reacted amine groups divided by the number of free amine groups before the chemical modification was calculated.40 Glycine was used to generate a standard curve. The hydrogen map of amine groups substituted with methacrylic moieties was profiled by using 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectroscopy.

1H NMR

Chemically modified HSA was lyophilized and dissolved (10 mg/mL) in deuterium oxide (Sigma-Aldrich) and stored at 4 °C until NMR data acquisition. 1H NMR spectra were acquired at 25 °C using a Bruker 500 MHz spectrometer with a spectral width of 10,000 ppm, 128 scans, 4 dummy scans, and a total acquisition time of 1.64 s. Solvent presaturation was employed to minimize the impact of water on the spectrum. Phase and baseline corrections were manually applied to obtain purely absorptive peaks. The double peaks at 5.4 and 5.7 ppm were used as an indicator of incorporated hydrogens attached to the double bond of methacrylic anhydride.

Assessment of AlMA Aggregates

To induce self-assembled aggregates, AlMA (0, 0.05, 0.6, and 2% DM; 2 mg/mL) was dissolved in PBS and allowed to stir in the dark at room temperature. The hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PdI) of the resulting self-assembled AlMA aggregates were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a nanoparticle analyzer (Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS90, Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis was conducted to study the aggregation of 20% AlMA. AlMA macromolecule solution was applied to a charged carbon–formvar-coated grid and stained (1% uranyl acetate, 1 min). The samples were then examined with the TEM (Hitachi H7600, Tokyo, Japan) at 80 kV. High-DM AlMA solution specimens with a concentration range of 0.1 ng/mL–10 mg/mL were subject to TEM measurements.

Transmittance Study

The light transmitted through the different prepolymer solutions with different concentrations of MA and AlMA was measured using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (OPTIZEN POP, Mecasys, Daejeon, Korea). For the measurement, the prepolymer solution was scanned (acquisition mode) from 200 to 900 nm at 5.0 nm intervals using quartz cuvettes with 10 mm path lengths. PBS was used as the blank. The collected absorbance data was used to calculate %T.

Preparation of Ultraviolet (UV)-Cross-Linked Hydrogels

Lyophilized AlMA was dissolved using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.5% w/v 2-hydroxy-1-(4-(hydroxyethyl) phenyl)-2-methyl-1-propanone (Irgacure 2959, CIBA Chemicals, Basel, Switzerland) to generate free radicals to initiate the photo-cross-linking reaction. Microscope slides (Marienfeld, Germany) were acylated with TMSPMA to chemically anchor the hydrogels on the surface.41 After being fully dissolved, the prepolymer solution was dropped onto the TMSPMA-coated glass slide between two cover glasses attached on both sides as a spacer (150 μm and 1 mm), after which the solution was covered by an additional cover glass with a photomask on top of the whole complex. The complex was placed on the UV light curing system (360–480 nm) and photopolymerized at 8.3 mW/cm2 (if not indicated) for various times as indicated. Photomasks with square patterns (dimensions: 500 μm × 500 μm) and round patterns (diameter: 500 μm) were designed using AutoCAD.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

To visualize the hydrogel internal network and the pore distribution, the matrices were lyophilized and sectioned to expose the cross-sectional surface. Prepared samples were gold/palladium sputter (Ion Sputter MC1000, Hitachi, Japan)-coated to 10 nm thickness, and images were examined at an accelerating voltage of 15.0 kV with a resolution of 1.5 nm by field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, S-4700, Hitachi, Japan).

Characterization of AlMA Hydrogels

Mechanical Properties

For the measurement of mechanical properties, test specimens were prepared by pipetting prepolymer solution (0.5% PI) onto Culturewell chambered coverslips of 1 mm thickness (8 mm diameter) and exposed to UV light (8.3 mw/cm2, 360–380 nm) for 150 s. To characterize the Young’s modulus E, the AFM indentation technique was applied. Here, the hydrogel sample was firstly immersed in 1× PBS in a petri dish mounted onto the AFM setup. Then, the AFM cantilever (DNP, Bruker, Camarillo, CA, USA) was positioned onto the sample with the assistance of an inverted microscope underneath the petri dish. The cantilever tip was then indented into the sample for the characterization. For each sample, six well-scattered points were selected randomly. Upon completion of the nanoindentation test, the corresponding force–depth curves were analyzed. Since the indentation depth in the micrometer scale is far larger than the radius of the AFM tip radius in the nanoscale, the theoretical model for conical indentation was properly applied to analyze the indentation results.42

Swelling Properties

For the measurement of swelling properties, the test specimens were fabricated by pipetting the prepolymer solution between two glass slides separated by a 1 mm spacer and exposed to UV light (8.3 mw/cm2, 360–380 nm) for 150 s. Immediately after the formation of the hydrogel, each sample was placed in PBS at 37 °C for 24 or 48 h. At each timepoint, the weight was recorded after removing excess PBS, and the samples were then lyophilized and weighed one more time. Finally, the mass swelling ratio was expressed as the ratio of swollen hydrogel mass to the mass of the dry polymer. The number of tested samples was 5 per group.

Enzymatic Degradation Profile

To determine the stability of hydrogel matrices under physiological conditions, polymerized hydrogels (55 μL, 20% w/v, and 150 s) were placed into a free-standing cylinder and incubated in 1 mL of 2.5 U/mL collagenase type II (Worthington Biochemical Corp., NJ, USA) at 37 °C with gentle shaking (< 150 rpm).43 The degradation profiles of the hydrogels were expressed as the percentage of remaining mass (%), which was calculated by dividing the initial mass (mg) of gels at 0 h by the remaining mass (mg) of gels at various timepoints based on dry weight recorded after freeze-drying. The hydrogels used in the analysis had varying DMs (27, 36, 51, and 58% DM; each corresponding to 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, and 0.6% MA used for the modification). Three replicates were made at nine different timepoints (0, 1, 3, 6, 10, 24, 35, 48, and 72 h after the incubation).

Contact Angle Measurement

To determine the surface hydrophilicity of the hydrogels, the surface glycerol contact angles of three different types of hydrogels were measured (room temperature) following the method described in the ASTM D5946 (“Standard test method for corona-treated polymer films using water contact angle measurements”) by using the Phoenix 300 Touch instrument (SEO). Samples were prepared with 10 and 20% w/v concentrations with 8 mm diameters and 1 mm thicknesses and directly cross-linked on the glass slide in a free-standing form. As a reference control, the same concentrations of polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA; MW 1000, Polysciences, Inc., USA) and GelMA hydrogels that are commonly used as biopolymers were chosen. The contact angle was measured by dropping 0.003–0.005 mL of glycerol solution onto the hydrogel matrices with a 27-gauge size needle and 3 mL volume syringe. Measurements were performed three times for each type of polymer and averaged with data variation expressed as standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV). The range of measurement was 10–180° with an accuracy of 0.1°.

Protein Adsorption

Total protein content was calculated by performing a Micro BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). To measure the protein adsorption on hydrogel surface, test samples were prepared by pipetting (10 μL) prepolymer solution (0.5% PI) onto Culturewell chambered coverslips of 155 μm thickness (3 mm diameter) and exposed to UV light (8.3 mw/cm2, 360–380 nm) for 20 s. Two different types of AlMA samples (10 and 20% w/v) were measured, and as a reference control, PEGDA and GelMA hydrogels that are commonly used as biopolymers were chosen (10 %w/v). The prepared samples were then immersed into 5 mL of protein solution with a concentration of 1 mg/mL for 30 min in Eppendorf tubes (5 mL). After the incubation, the amount of attached protein on a hydrogel were calculated as follows:

In Vitro Studies

Cell Culture

For the cell culture of the H9C2 rat heart myoblast and the NIH-3T3 cell line (purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank, Seoul, Korea), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1× penicillin/streptomycin (Welgene, Daegu, Korea) were used. Both cell lines were grown at 5% CO2 and 37 °C conditions. Cells were passaged at least twice per week at subconfluency in a 1:3 ratio, and the media was changed once every 2 days. Human endothelial progenitor cells (hEPCs) were kindly provided by Prof. S.M. Kwon (Pusan University, Pusan, Korea).44,45 The hEPCs were cultured on gelatin-coated (1%) dishes in EC basal medium 2 (EBM-2, Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) supplemented with 5% FBS, EGM-2 growth factor mixture, and 1× penicillin/streptomycin (5% CO2 at 37 °C).

Cell Adhesion

Five different types of biopolymers were used in the cell adhesion study for comparative analysis: GelMA, 10% AlMA (0.6 and 2% DM), and 20% AlMA (0.6 and 2% DM) hydrogels. Hydrogel sheets (8 mm diameter × 150 μm height) were fabricated onto TMSPMA-coated glass slides by using a UV intensity of 8.3 mW/cm2 for 25 s. Polymerized hydrogels were washed with DPBS prior to incubation in culture media for 12 h. Cell suspensions containing 2.5 × 105 cells/mL of cell lines (H9C2 or NIH-3T3) or primary cells (hEPC) were pipetted onto the hydrogel surface and incubated for 1 h prior to gentle washing with DPBS. Cells that adhered to hydrogel sheets were stained using a LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) to evaluate cell viability after 24 h. On day 3, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde solution, and cytoskeleton structures were stained with Phalloidin-FITC (F-actin filament; Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and DAPI (cell nuclei; Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA).

Cell Encapsulation

For the 3D cell encapsulation study, cell lines (H9C2 or NIH-3T3) and primary cells (hEPC) were suspended in the 10 and 20% w/v AlMA prepolymer with different DMs at 2 × 106 cells/mL. The cells containing prepolymer solution with 0.5% PI were exposed to a 8.3 mW/cm2 UV light for 25 s on the TMSPMA-coated glass between 150 μm spacers. The cell-encapsulated hydrogels were thoroughly washed with DPBS and incubated for 4 days. Cell viability was measured by using a LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA).

In Vivo Studies

Animal and Hydrogel Disk Implantation

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 30; 7 weeks old; 300–330 g) were purchased from Orient Bio (Seongnam, Korea) and were maintained under a controlled environment in specific pathogen-free conditions. All experiments were carried out following protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Konkuk University (approval no. KU 17025). Four hydrogel disks were subcutaneously implanted for each rat. Rats were anesthetized by continuous inhalation of 2% isoflurane gas. Incisions were made on the central dorsal area to reach the subcutaneous space. Then, subcutaneous pockets were created for the implantation of the hydrogel disks. After implantation, the skin incisions were closed using interrupted 3-0 silk sutures.

Immunohistological Analysis

The implanted hydrogels were harvested at days 3, 7, and 14 for each group and then fixed in Bouin’s solution (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). The paraffin block samples were sectioned (3 μm) and permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). Prepared sections were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to identify the nuclei gathering into the surrounding tissues and Masson’s trichrome staining for collagen and blood vessel distribution around the implanted hydrogel. Sections were further stained with CD31 (1:400, Novus, CO, USA) as a marker for blood vessels and were incubated overnight at 4 °C. CD45 (1:500, ab10558, Abcam, Tokyo, Japan) was used to examine the migration of macrophages into the transplanted hydrogels, and the sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C. Secondary Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated antibodies (Invitrogen, MA, USA) were diluted (1: 500) and reacted at room temperature for 2 h. The nucleus was stained by dilution to 1:10000 with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) with counterstain.

Statistical Analysis

All parametric data are indicated as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Unpaired Student’s t tests and one- or two-way ANOVA were performed to determine significant differences with the appropriate post-tests using GraphPad Prism5 (GraphPad, San Diego, USA). A P value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

This paper was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2018R1D1A1B05047274), the Technology Innovation Program 20008650 funded by the Ministry of Trade Industry and Energy, and Konkuk University’s research support program for its faculty on sabbatical leave in 2019. S.R.S. acknowledges funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01AR074234 and R21EB026824), the AHA Innovative Project Award (19IPLOI34660079), the Gillian Reny Stepping Strong Center for Trauma Innovation, and the Innovation Evergreen Fund Award in Brigham and Women’s Hospital. J.Y.M. and S.N. were funded by the KBRI basic research program through the Korea Brain Research Institute funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (21-BR-03-01). H.L. is now employed by the Department of Food Science and Technology, University of California, Davis, Davis, California, United States. We would like to thank Prof. S.M. Kwon (Pusan University, Pusan, South Korea) for providing human endothelial progenitor cells (hEPCs).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c04292.

Supporting methods, cross-sectional SEM images, and elastic modulus of AlMA hydrogels; water contact angle images of 10% GelMA and 10% PEGDA hydrogels; F-actin and DAPI image of cultured H9C2 on the 10% GelMA hydrogel on day 3; cultured NIH-3T3 and H9C2 cell behavior on the 10 and 20% AlMA hydrogels; live/dead images of encapsulated hEPCs in the AlMA hydrogels; supporting in vivo characterizations (PDF)

Author Contributions

◆ H.Y., H.L, and S.Y.S. contributed equally to this work.

Author Contributions

H.B. and S.R.S. designed the experiments; H.J.Y., S.Y.S., H.L., H.J., W.L., J.W.S., G.K., J.Y.M., K.Z., K.-W., S.N., and Y.J.P. performed the experiments. H.B., S.R.S., H.J.Y., H.L. and Y.A.J. arranged the data and wrote the manuscript; H.B., S.R.S., H.J.Y., and Y.A.J. revised the manuscript. All authors significantly contributed to the study and to the interpretation of the data.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Grant M. E. From collagen chemistry towards cell therapy - a personal journey. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2007, 88, 203–214. 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2007.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. T.; Milby A. H.; Ikuta K.; Poudel S.; Pfeifer C. G.; Elliott D. M.; Smith H. E.; Mauck R. L. A radiopaque electrospun scaffold for engineering fibrous musculoskeletal tissues: Scaffold characterization and in vivo applications. Acta Biomater. 2015, 26, 97–104. 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson C. E.; Kim A. J.; Adolph E. J.; Gupta M. K.; Yu F.; Hocking K. M.; Davidson J. M.; Guelcher S. A.; Duvall C. L. Tunable delivery of siRNA from a biodegradable scaffold to promote angiogenesis in vivo. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 607–614. 10.1002/adma.201303520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil P.; Martin J. R.; Sarett S. M.; Pollins A. C.; Cardwell N. L.; Davidson J. M.; Guelcher S. A.; Nanney L. B.; Duvall C. L. Porcine Ischemic Wound-Healing Model for Preclinical Testing of Degradable Biomaterials. Tissue Eng., Part C 2017, 23, 754–762. 10.1089/ten.tec.2017.0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christman K. L.; Vardanian A. J.; Fang Q.; Sievers R. E.; Fok H. H.; Lee R. J. Injectable fibrin scaffold improves cell transplant survival, reduces infarct expansion, and induces neovasculature formation in ischemic myocardium. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 44, 654–660. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spang M. T.; Christman K. L. Extracellular matrix hydrogel therapies: In vivo applications and development. Acta Biomater. 2018, 68, 1–14. 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kook Y. M.; Hwang S.; Kim H.; Rhee K. J.; Lee K.; Koh W. G. Cardiovascular tissue regeneration system based on multiscale scaffolds comprising double-layered hydrogels and fibers. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20321. 10.1038/s41598-020-77187-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolfi A. L.; Behun M. N.; Yates C. C.; Brown B. N.; Kulkarni M. Beyond Growth Factors: Macrophage-Centric Strategies for Angiogenesis. Curr. Pathobiol. Rep. 2020, 8, 111–120. 10.1007/s40139-020-00215-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du P.; Suhaeri M.; Subbiah R.; Van S. Y.; Park J.; Kim S. H.; Park K.; Lee K. Elasticity modulation of fibroblast-derived matrix for endothelial cell vascular morphogenesis and mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Tissue Eng., Part A 2016, 22, 415–426. 10.1089/ten.tea.2015.0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kook Y. M.; Kim H.; Kim S.; Heo C. Y.; Park M. H.; Lee K.; Koh W. G. Promotion of vascular morphogenesis of endothelial cells co-cultured with human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells using polycaprolactone/gelatin nanofibrous scaffolds. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 117. 10.3390/nano8020117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin S.; Zhang W.; Zhang Z.; Jiang X. Recent Advances in Scaffold Design and Material for Vascularized Tissue-Engineered Bone Regeneration. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2019, 8, 1801433. 10.1002/adhm.201801433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goonoo N.; Bhaw-Luximon A. Mimicking growth factors: role of small molecule scaffold additives in promoting tissue regeneration and repair. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 18124–18146. 10.1039/C9RA02765C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo B. B.; Park M. R.; Song S. C. Sustained Release of Exendin 4 Using Injectable and Ionic-Nano-Complex Forming Polymer Hydrogel System for Long-Term Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 15201–15211. 10.1021/acsami.8b19669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baler K.; Martin O.; Carignano M.; Ameer G.; Vila J.; Szleifer I. Electrostatic unfolding and interactions of albumin driven by pH changes: a molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2014, 118, 921–930. 10.1021/jp409936v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M.; Bahrami S.; Ravari S. B.; Zangabad P. S.; Mirshekari H.; Bozorgomid M.; Shahreza S.; Sori M.; Hamblin M. R. Albumin nanostructures as advanced drug delivery systems. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 2016, 13, 1609–1623. 10.1080/17425247.2016.1193149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis G. L. Albumin and mammalian cell culture: implications for biotechnology applications. Cytotechnology 2010, 62, 1–16. 10.1007/s10616-010-9263-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldecoa C.; Llau J. V.; Nuvials X.; Artigas A. Role of albumin in the preservation of endothelial glycocalyx integrity and the microcirculation: a review. Ann. Intensive Care 2020, 10, 85. 10.1186/s13613-020-00697-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Fang Z.; Zhang X.; Cai H.; Zhao Y.; Gu W.; Yang X.; Wu Y. A Self-Assembled “Albumin–Conjugate” Nanoprobe for Near Infrared Optical Imaging of Subcutaneous and Metastatic Tumors. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 327–334. 10.1021/acsabm.9b00839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong J.; Zhao J.; Justin A. W.; Markaki A. E. Albumin-based hydrogels for regenerative engineering and cell transplantation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 116, 3457–3468. 10.1002/bit.27167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raja S. T. K.; Thiruselvi T.; Mandal A. B.; Gnanamani A. pH and redox sensitive albumin hydrogel: A self-derived biomaterial. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15977. 10.1038/srep15977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossover O.; Cohen N.; Lewis J. A.; Berkovitch Y.; Peled E.; Seliktar D. Growth Factor Delivery for the Repair of a Critical Size Tibia Defect Using an Acellular, Biodegradable Polyethylene Glycol–Albumin Hydrogel Implant. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 100–111. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b00672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amdursky N.; Mazo M. M.; Thomas M. R.; Humphrey E. J.; Puetzer J. L.; St-Pierre J.-P.; Skaalure S. C.; Richardson R. M.; Terracciano C. M.; Stevens M. M. Elastic serum-albumin based hydrogels: mechanism of formation and application in cardiac tissue engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 5604–5612. 10.1039/C8TB01014E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; Gao L.; Peng J.; Xing M.; Han Y.; Wang X.; Xu Y.; Chang J. Bioglass Activated Albumin Hydrogels for Wound Healing. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2018, 7, 1800144. 10.1002/adhm.201800144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong J.; Zhao J.; Levy G. K.; Macdonald J.; Justin A. W.; Markaki A. E. Functionalisation of a heat-derived and bio-inert albumin hydrogel with extracellular matrix by air plasma treatment. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12429. 10.1038/s41598-020-69301-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iemma F.; Spizzirri U. G.; Muzzalupo R.; Puoci F.; Trombino S.; Picci N. Spherical hydrophilic microparticles obtained by the radical copolymerisation of functionalised bovine serum albumin. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2004, 283, 250–256. [Google Scholar]

- Kellis J. T. Jr.; Nyberg K.; Sali D.; Fersht A. R. Contribution of hydrophobic interactions to protein stability. Nature 1988, 333, 784–786. 10.1038/333784a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Zocchi M.; Andreasen A.; Zocchi G. Osmotic pressure contribution of albumin to colloidal interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96, 6711–6715. 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeneveld J. A. B. Albumin and artificial colloids in fluid management: where does the clinical evidence of their utility stand?. Crit. Care 2000, 4, S16. 10.1186/cc965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirahama H.; Lee B. H.; Tan L. P.; Cho N.-J. Precise Tuning of Facile One-Pot Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) Synthesis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31036. 10.1038/srep31036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maibaum L.; Dinner A. R.; Chandler D. Micelle Formation and the Hydrophobic Effect. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004, 108, 6778–6781. 10.1021/jp037487t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V.; Khullar P.; Dave P. N.; Kaur N. Micelles, mixed micelles, and applications of polyoxypropylene (PPO)-polyoxyethylene (PEO)-polyoxypropylene (PPO) triblock polymers. Int. J. Ind. Chem. 2013, 4, 12. 10.1186/2228-5547-4-12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park H.; Park K.; Shalaby W. S.. Biodegradable Hydrogels for Drug Delivery; Taylor & Francis, CRC Press: England, 2011; p 169. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Sun T.; Jiang C. Biomacromolecules as carriers in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2018, 8, 34–50. 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M.; Ben-Josef E.; Robb R.; Vedaie M.; Seum S.; Thirumoorthy K.; Palanichamy K.; Harbrecht M.; Chakravarti A.; Williams T. M. Caveolae-Mediated Endocytosis Is Critical for Albumin Cellular Uptake and Response to Albumin-Bound Chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 5925–5937. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scelsi A.; Bochicchio B.; Smith A.; Workman V. L.; Castillo Diaz L. A.; Saiani A.; Pepe A. Tuning of hydrogel stiffness using a two-component peptide system for mammalian cell culture. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 2019, 107, 535–544. 10.1002/jbm.a.36568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabnis A.; Rahimi M.; Chapman C.; Nguyen K. T. Cytocompatibility studies of an in situ photopolymerized thermoresponsive hydrogel nanoparticle system using human aortic smooth muscle cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 2009, 91A, 52–59. 10.1002/jbm.a.32194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H.; Qian K.; Cai J.; Yang Y.; Zhu L.; Liu B. Therapy for Gastric Cancer with Peritoneal Metastasis Using Injectable Albumin Hydrogel Hybridized with Paclitaxel-Loaded Red Blood Cell Membrane Nanoparticles. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 1100–1112. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.8b01557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. J.; Kim J. S.; Papadopoulos J.; Wook Kim S.; Maya M.; Zhang F.; He J.; Fan D.; Langley R.; Fidler I. J. Circulating monocytes expressing CD31: implications for acute and chronic angiogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 174, 1972–1980. 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol J. W.; Koshy S. T.; Bae H.; Hwang C. M.; Yamanlar S.; Khademhosseini A. Cell-laden microengineered gelatin methacrylate hydrogels. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 5536–5544. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbate V.; Kong X.; Bansal S. S. Photocrosslinked bovine serum albumin hydrogels with partial retention of esterase activity. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2012, 50, 130–136. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang C. M.; Sim W. Y.; Lee S. H.; Foudeh A. M.; Bae H.; Lee S.-H.; Khademhosseini A. Benchtop fabrication of PDMS microstructures by an unconventional photolithographic method. Biofabrication 2010, 2, 045001 10.1088/1758-5082/2/4/045001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Cripps A. C. Critical review of analysis and interpretation of nanoindentation test data. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 200, 4153–4165. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2005.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camci-Unal G.; Cuttica D.; Annabi N.; Demarchi D.; Khademhosseini A. Synthesis and Characterization of Hybrid Hyaluronic Acid-Gelatin Hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 1085–1092. 10.1021/bm3019856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Y. W.; Heo S. C.; Lee T. W.; Park G. T.; Yoon J. W.; Jang I. H.; Kim S. C.; Ko H. C.; Ryu Y.; Kang H.; Ha C. M.; Lee S. C.; Kim J. H. N-Acetylated Proline-Glycine-Proline Accelerates Cutaneous Wound Healing and Neovascularization by Human Endothelial Progenitor Cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43057. 10.1038/srep43057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G.; Lee J. H.; Jang J.; Lee D. H.; Kong J. S.; Kim B. S.; Choi Y. J.; Jang W. B.; Hong Y. J.; Kwon S. M.; Cho D. W. Tissue Engineered Bio-Blood-Vessels Constructed Using a Tissue-Specific Bioink and 3D Coaxial Cell Printing Technique: A Novel Therapy for Ischemic Disease. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1700798. 10.1002/adfm.201700798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.